Quantification of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Hypertensive Subjects in Active Romanian Population Using New Echocardiographic, Biological and Atherogenic Markers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

- Control group (C): Newly diagnosed hypertensive patients without known major cardiovascular events (n = 60).

- Group P1: Hypertensive patients with concomitant dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 80).

- Group P2: Hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia, with a documented history of at least one major cardiovascular event (coronary heart disease, stroke, or peripheral artery disease) and/or atrial fibrillation/flutter (n = 80).

- Group P3: Hypertensive patients, with or without type 2 diabetes, who had recently experienced a major cardiovascular event (coronary heart disease, stroke, or peripheral artery disease) and/or atrial fibrillation/flutter (n = 80).

- age between 35 and 85 years;

- diagnosis of arterial hypertension according to current guidelines;

- ability to provide informed consent.

- type 1 diabetes mellitus;

- history of any malignancy prior to enrolment;

- severe non-cardiovascular comorbidities limiting life expectancy or precluding follow-up;

- poor echocardiographic window precluding reliable strain analysis.

2.3. Data Collection and Clinical Assessment

2.4. Laboratory and Biomarker Assessment

- Lipid profile: total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), non-HDL cholesterol, and total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio.

- Glycemic and metabolic markers: fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and serum homocysteine.

- Inflammatory marker: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Atherogenic enzyme marker: paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity.

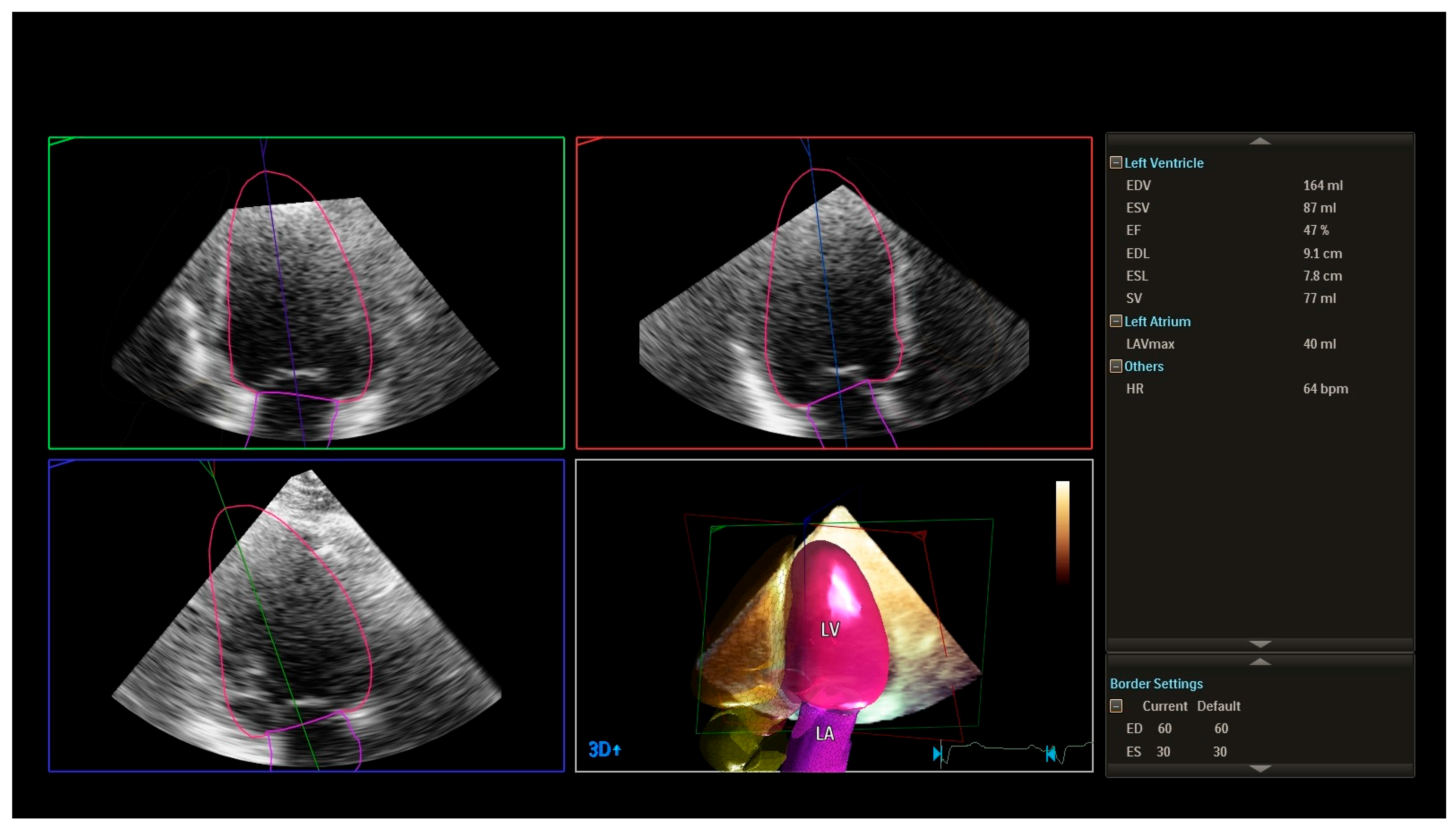

2.5. Echocardiographic Assessment

- left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, 2D);

- left ventricular dimensions and wall thickness;

- left atrial size;

- indices of diastolic function (E/A ratio, E/e’, deceleration time, left atrial size, and additional parameters as required).

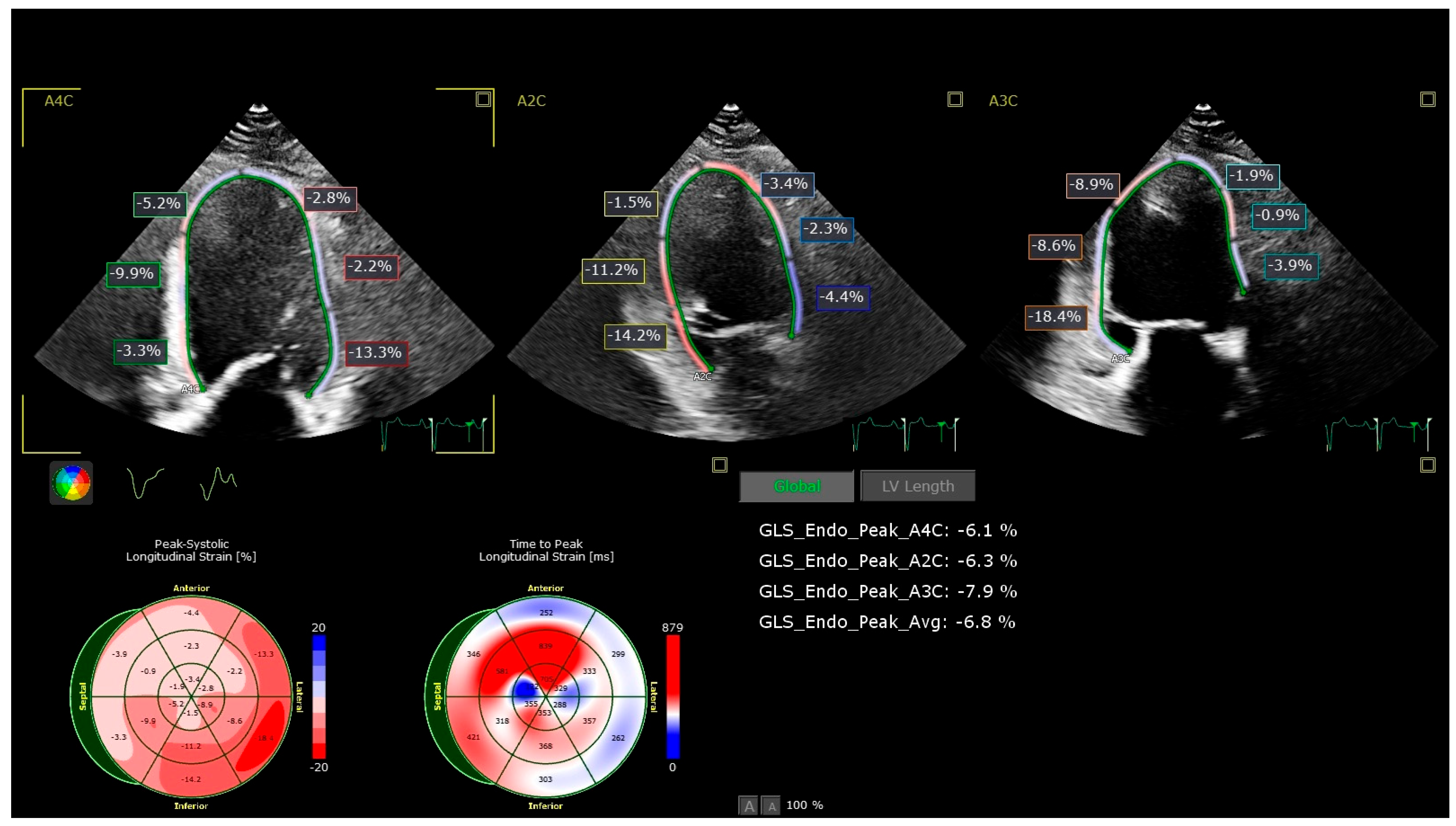

- Global longitudinal strain (GLS): Assessed by 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography using apical views (four-chamber, two-chamber, and long-axis). The endocardial border was manually traced, and tracking was automatically performed, with manual adjustments as necessary. A GLS value less negative than −19% (i.e., >−19%) was considered abnormal based on vendor-specific reference ranges.

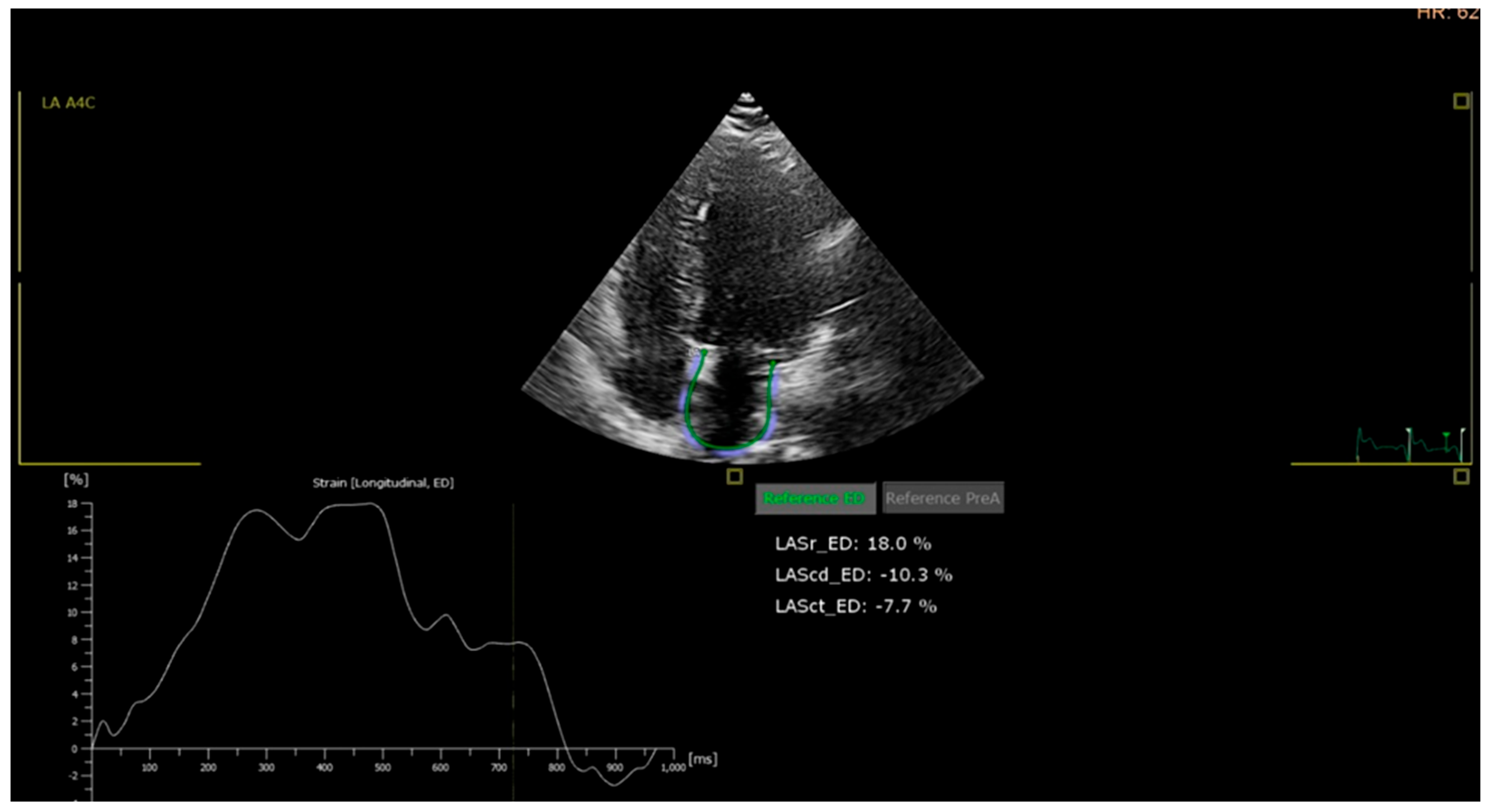

- Left atrial (LA) strain: LA reservoir strain was measured using speckle-tracking from apical four-chamber views focused on the left atrium. A value below 35% was considered abnormal, based on the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval observed in the control group and supported by literature data.

2.6. Definition of Outcomes

- coronary heart disease (including myocardial infarction and documented coronary artery disease requiring revascularization or associated with significant stenosis);

- ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke;

- peripheral artery disease requiring intervention or documented by imaging; and/or

- the presence of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.

2.7. Risk Score Development (PulsIn)

- classical clinical risk factors (age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, diabetes, lipid profile);

- echocardiographic parameters (LVEF, diastolic dysfunction, GLS, LA strain, 3D LVEF);

- inflammatory marker (CRP);

- atherogenic markers (non-HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio, PON1);

- presence of arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation/flutter).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

- Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables;

- Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables;

- χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate.

- Logistic regression to estimate the association between predictors and the presence of major cardiovascular events and to obtain odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

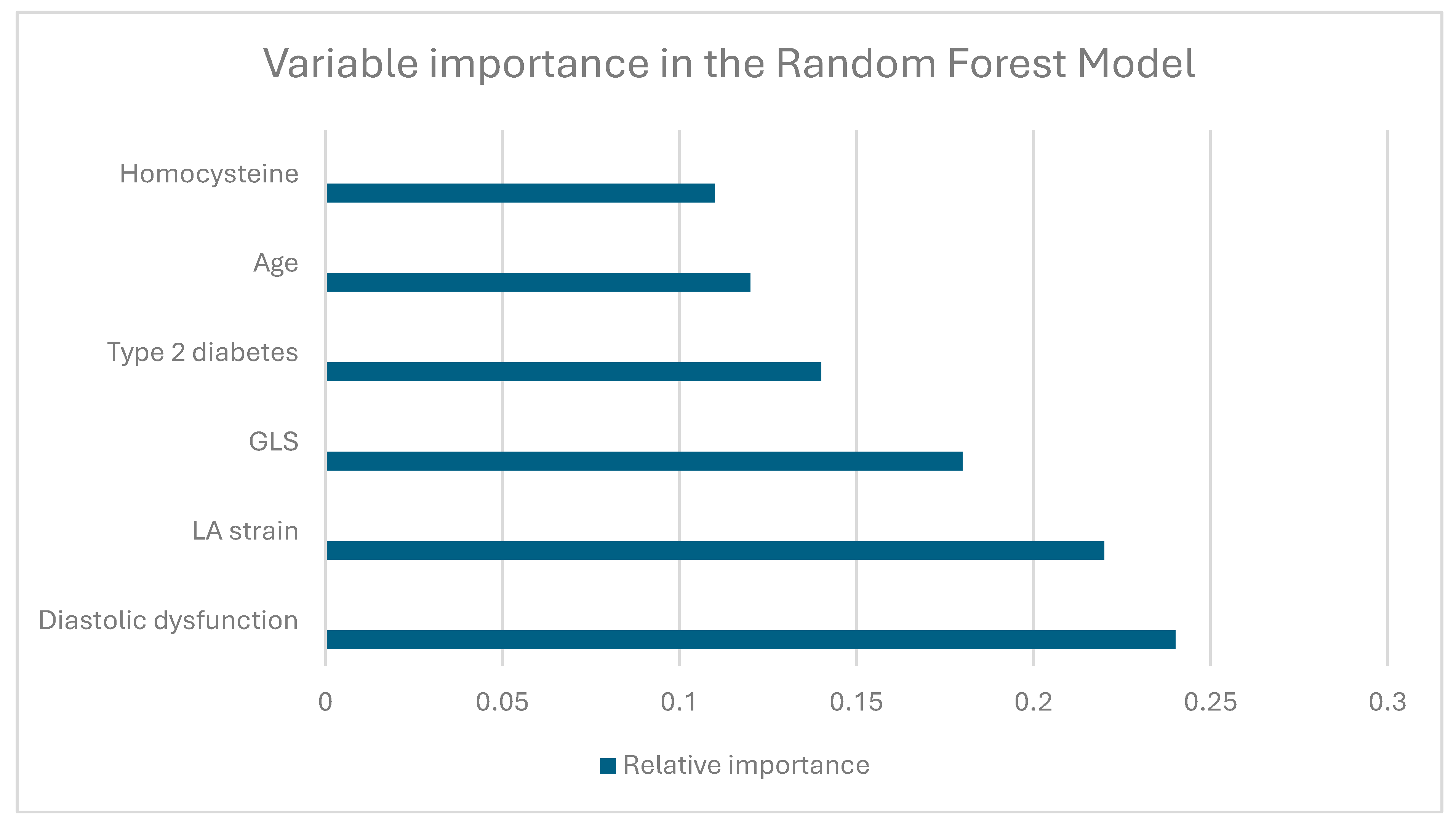

- Random forest and XGBoost classifiers as ensemble machine learning methods to capture non-linear relationships and interactions between variables.

- area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC);

- sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy at selected probability thresholds;

- calibration plots where applicable.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Laboratory and Echocardiographic Parameters

3.3. Model Performance and Feature Importance

3.3.1. Logistic Regression Model

3.3.2. Random Forest Model

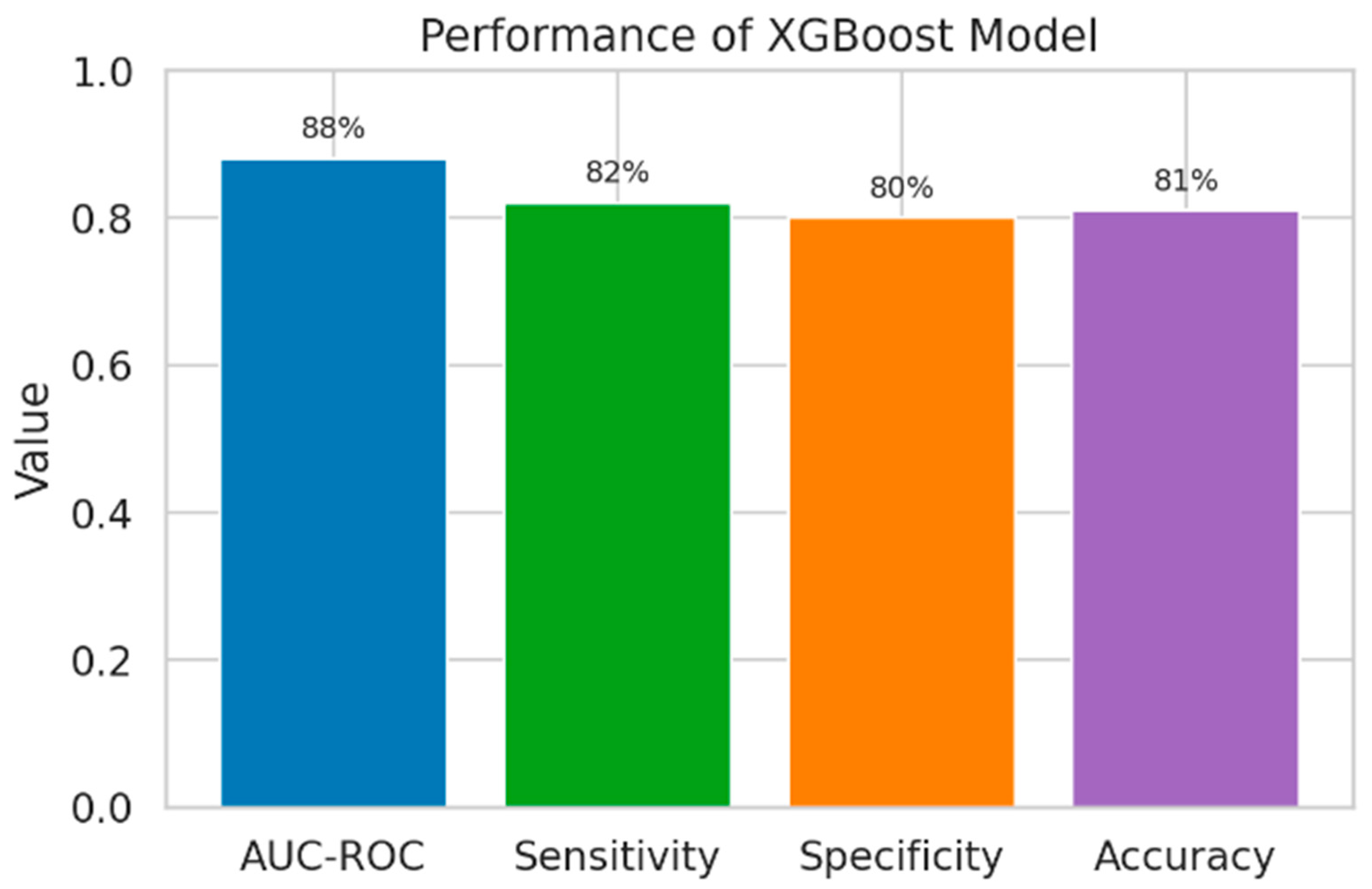

3.3.3. XGBoost Model

3.3.4. Comparison of Model Performance

3.3.5. CV Risk Score Comparison

4. Discussions

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Differences in Classical and Extended Markers Between Groups

4.3. Performance of PulsIn vs. Traditional Risk Estimation

4.4. Importance of the New Parameters That Were Included in PulsIn Calculator

4.5. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.6. Clinical Implications

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorobantu, M.; Tautu, O.F.; Dimulescu, D.; Sinescu, C.; Gusbeth-Tatomir, P.; Arsenescu-Georgescu, C.; Mitu, F.; Lighezan, D.; Pop, C.; Babes, K.; et al. Perspectives on hypertension prevalence, treatment and control in a high cardiovascular risk East European country: Data from the SEPHAR III survey. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, M.; Vijiac, A.E.; Gheorghe Fronea, O.F. The SEPHAR-FUp 2020 Project (Study for the Evaluation of Prevalence of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk in Romania—Follow-up 2020). J. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 7, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Timmis, A.; Vardas, P.; Townsend, N.; Torbica, A.; Katus, H.; De Smedt, D.; Gale, C.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Petersen, S.E.; Huculeci, R.; et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 716–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCORE2 Working Group and ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: New models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2439–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, R.M.; Pyörälä, K.; Fitzgerald, A.P.; Sans, S.; Menotti, A.; De Backer, G.; De Bacquer, D.; Ducimetière, P.; Jousilahti, P.; Keil, U.; et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur. Heart J. 2003, 24, 987–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossello, X.; Dorresteijn, J.A.; Janssen, A.; Lambrinou, E.; Scherrenberg, M.; Bonnefoy-Cudraz, E.; Cobain, M.; Piepoli, M.F.; Visseren, F.L.J.; Dendale, P. Risk prediction tools in cardiovascular disease prevention: A report from the ESC Prevention of CVD Programme led by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology in collaboration with the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association and the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- SCORE2-OP Working Group and ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2-OP risk prediction algorithms: Estimating incident cardiovascular event risk in older persons in four geographical risk regions. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2455–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Buring, J.E.; Rifai, N.; Cook, N.R. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: The Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA 2007, 297, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: Revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1332–e1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, G.S.; Palatini, P.; Parati, G.; O’bRien, E.; Januszewicz, A.; Lurbe, E.; Persu, A.; Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; on behalf of the European Society of Hypertension Council and the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring and Cardiovascular Variability. 2021 European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement: A consensus document. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.; Maxwell, A.P.; Brazil, D.P. The potential of albuminuria as a biomarker of diabetic complications. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 35, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirica, B.M.; Mosenzon, O.; Bhatt, D.L.; Steg, P.G.; McGuire, D.K.; Im, K. Cardiovascular outcomes according to urinary albumin and kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: Observations from the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, J.I.; Farag, Y.M.K.; Durthaler, J. Albuminuria: An underappreciated risk factor for cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieweke, J.T.; Hagemus, J.; Biber, S.; Stöbe, S.; Dominik, B.; Gerrit, M.G.; Sven, S.; Jonathan, P.T.; Anselm, A.D.; Jonas, N.; et al. Echocardiographic parameters to predict atrial fibrillation in clinical routine: The EAHsy-AF risk score. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 851474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lancellotti, P.; Price, S.; Edvardsen, T.; Cosyns, B.; Neskovic, A.N.; Dulgheru, R.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Hassager, C.; Pasquet, A.; Gargani, L.; et al. The use of echocardiography in acute cardiovascular care: Recommendations of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2015, 4, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kou, S.; Caballero, L.; Dulgheru, R.; Voilliot, D.; De Sousa, C.; Kacharava, G.; Athanassopoulos, G.D.; Barone, D.; Baroni, M.; Cardim, N.; et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac chamber size: Results from the NORRE study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2014, 15, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips. Bringing 3D Ultrasound into Practice for Cardiac Quantification: Philips Dynamic Heart Model; Koninklijke Philips N.V.: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Xue, H.Y.; Ye, Y.Q. Heart Model AI three-dimensional echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular function and parameter setting. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 7971–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.C.C.; Kitano, T.; Chu, P.H.; Habibi, M.; Negishi, K.; Marwick, T.H. Left ventricular volume and ejection fraction measurements by fully automated three-dimensional echocardiography left chamber quantification software versus CMR: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/76/mdrd-gfr-equation (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Available online: https://kdigo.org/guidelines/acute-kidney-injury/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Chin’ombe, N.; Msengezi, O.; Matarira, H. Microalbuminuria in patients with chronic kidney disease at Parirenyatwa Hospital in Zimbabwe. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2013, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.M.; Bali, A.; Tikaria, R. Microalbuminuria. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563255/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- González-Lamuño, D.; Arrieta-Blanco, F.J.; Fuentes, E.D.; Forga-Visa, M.; Morales-Conejo, M.; Peña-Quintana, L.; Vitoria-Miñana, I. Hyperhomocysteinemia in adult patients: A treatable metabolic condition. Nutrients 2024, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaddon, A.; Miller, J.W. Homocysteine: A retrospective and prospective appraisal. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1179807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, R.B.; Pencina, M.J. Clinical usefulness of the Framingham cardiovascular risk profile beyond its statistical performance. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.; Cabré, J.J.; Martín, F.; Piñol, J.L.; Basora, J.; Bladé, J. The Framingham function overestimates stroke risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome among the Spanish population. Aten. Primaria 2005, 35, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Diego, P.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; Guembe, M.J.; Viñes, J.J.; Vila, J. Adaptation of the Framingham-Wilson coronary risk equation for the population of Navarra (RICORNA). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2009, 62, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyöngyösi, H.; Szőllősi, G.J.; Csenteri, O.; Jancsó, Z.; Móczár, C.; Torzsa, P.; Andréka, P.; Vajer, P.; Nemcsik, J. Differences between SCORE, Framingham Risk Score, and estimated pulse wave velocity-based vascular age calculation methods based on data from the Three Generations Health Program in Hungary. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abohelwa, M.; Kopel, J.; Shurmur, S.; Saba, M.; Nugent, K. The Framingham Study on cardiovascular disease risk and stress-defenses: A historical review. J. Vasc. Dis. 2023, 2, 122–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, R.B.; Pencina, M.J.; Massaro, J.M.; Coady, S. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment: Insights from Framingham. Glob. Heart 2013, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S.; Levy, D.; Vasan, R.S.; Wang, T.J. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases: A historical perspective. Lancet 2014, 383, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, W.J.; Polansky, J.M.; Boscardin, W.J.; Fung, K.; Steinman, M.A. Coronary risk assessment by point-based versus equation-based Framingham models: Implications for clinical care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, A.; Jahangiry, L.; Khezri, R.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Ponnet, K. Framingham risk scores for determining the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in adults living in northwest Iran: A population-based study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, J.; Young, R.; McClelland, R.L.; Delaney, J.C.; Polonsky, T.S.; Dawood, F.Z.; Blaha, M.J.; Miedema, M.D.; Sibley, C.T.; Carr, J.J.; et al. Utility of nontraditional risk markers in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, R.L.; Jorgensen, N.W.; Budoff, M.; Blaha, M.J.; Post, W.S.; Kronmal, R.A.; Bild, D.E.; Shea, S.; Liu, K.; Wat-son, K.E.; et al. 10-Year Coronary Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Coronary Artery Calcium and Traditional Risk Factors: Derivation in the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) With Validation in the HNR (Heinz Nixdorf Recall) Study and the DHS (Dallas Heart Study). JACC J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, N.R. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 2007, 115, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R. Statistical evaluation of prognostic versus diagnostic models: Beyond the ROC curve. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, I.; Elkhoudri, N.; Hilali, A. Major limitations of cardiovascular risk scores. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2024, 2024, 4133365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemann, B.A.; Bimson, W.F.; Taylor, A.J. The Framingham Risk Score: An appraisal of its benefits and limitations. Am. Heart Hosp. J. 2007, 5, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofogianni, A.; Stalikas, N.; Antza, C.; Tziomalos, K. Cardiovascular risk prediction models and scores in the era of personalized medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, R.B.; Vasan, R.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Cobain, M.; Massaro, J.M.; Kannel, W.B. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalam, K.; Otahal, P.; Marwick, T.H. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014, 100, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhanawar, M.; Shekhanawar, S.M.; Krisnaswamy, D.; Patil, M. Paraoxonase-1 activity as an antioxidant in coronary artery disease. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Trentini, A.; Marsillach, J.; D’Amuri, A.; Bosi, C.; Roncon, L.; Passaro, A.; Zuliani, G.; Mackness, M.; Cervellati, C. Paraoxonase-1 arylesterase activity levels in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Dis. Markers. 2022, 2022, 4264314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunmoogam, N.; Naidoo, P.; Chilton, R. Paraoxonase (PON)-1: Genetics, structure, polymorphisms and clinical relevance. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppen, E.G.; Bakker, S.J.L.; James, R.W.; Dullaart, R.P.F. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity is associated with light-to-moderate alcohol consumption: The PREVEND cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou-Bonafonte, J.M.; Gabás-Rivera, C.; Navarro, M.A.; Osada, J. PON1 and Mediterranean diet. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4068–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Carvajal, A.J.; Solà, I.; Lathyris, D.; Dayer, M. Homocysteine-lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD006612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hankey, G.J.; Eikelboom, J.W. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Lancet 1999, 354, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma Reis, R. Homocysteinemia and vascular disease: Where we stand in 2022. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2022, 41, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Lin, C.F.; Yeh, H.I. Critical appraisal of the role of serum albumin in cardiovascular disease. Biomark. Res. 2017, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 300) | C (n = 60) | P1 (n = 80) | P2 (n = 80) | P3 (n = 80) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.2 ± 9.4 | 52.1 ± 7.8 | 57.9 ± 8.6 | 60.3 ± 9.1 | 62.0 ± 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 168 (56.0) | 30 (50.0) | 46 (57.5) | 48 (60.0) | 44 (55.0) | 0.62 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 142 ± 16 | 138 ± 14 | 144 ± 15 | 145 ± 17 | 143 ± 16 | 0.04 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 86 ± 9 | 84 ± 8 | 87 ± 9 | 88 ± 10 | 85 ± 9 | 0.08 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.4 ± 4.2 | 28.1 ± 3.9 | 30.2 ± 4.3 | 29.8 ± 4.1 | 29.6 ± 4.5 | 0.03 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 96 (32.0) | 18 (30.0) | 25 (31.3) | 26 (32.5) | 27 (33.8) | 0.94 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 240 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 240 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | <0.001 |

| History of MACE, n (%) | 160 (53.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 80 (100) | 80 (100) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, n (%) | 90 (30.0) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.5) | 40 (50.0) | 40 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Variable | C (n = 60) | P1 (n = 80) | P2 (n = 80) | P3 (n = 80) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 210 ± 38 | 228 ± 42 | 230 ± 45 | 225 ± 40 | 0.02 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 130 ± 32 | 142 ± 35 | 144 ± 36 | 140 ± 34 | 0.03 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 49 ± 11 | 45 ± 10 | 44 ± 9 | 43 ± 9 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 150 (110–190) | 180 (140–230) | 190 (150–240) | 185 (145–235) | 0.001 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 161 ± 37 | 183 ± 41 | 186 ± 43 | 182 ± 39 | 0.001 |

| TC/HDL ratio | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 2.1 (1.0–3.4) | 3.0 (1.8–4.8) | 3.6 (2.1–5.9) | 3.8 (2.3–6.2) | <0.001 |

| Homocysteine, µmol/L | 11.5 ± 3.0 | 13.2 ± 3.6 | 14.1 ± 3.8 | 14.4 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| PON1 activity, U/L | 120 ± 35 | 105 ± 32 | 98 ± 30 | 95 ± 28 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 92 ± 18 | 85 ± 16 | 80 ± 18 | 78 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | 12 (7–20) | 20 (12–38) | 30 (18–55) | 32 (20–60) | <0.001 |

| Microalbuminuria, n (%) | 6 (10.0) | 20 (25.0) | 30 (37.5) | 32 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| Variable | C (n = 60) | P1 (n = 80) | P2 (n = 80) | P3 (n = 80) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV end-diastolic diameter, mm | 49 ± 4 | 50 ± 5 | 51 ± 5 | 52 ± 5 | 0.01 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 96 ± 18 | 104 ± 20 | 112 ± 22 | 115 ± 24 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (2D), % | 60 ± 4 | 58 ± 5 | 55 ± 6 | 52 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (3D), % | 59 ± 5 | 57 ± 6 | 53 ± 7 | 50 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic dysfunction, n (%) | 10 (16.7) | 30 (37.5) | 50 (62.5) | 55 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| GLS, % | −20.5 ± 1.8 | −19.0 ± 2.0 | −17.5 ± 2.2 | −16.8 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal GLS (<−19%), n (%) | 8 (13.3) | 28 (35.0) | 50 (62.5) | 55 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 26 ± 5 | 30 ± 6 | 34 ± 7 | 36 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| LA strain, % | 42 ± 6 | 38 ± 7 | 34 ± 8 | 32 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal LA strain (<35%), n (%) | 6 (10.0) | 24 (30.0) | 48 (60.0) | 52 (65.0) | <0.001 |

| B | S.E. | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for EXP(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender | 0.104 | 0.302 | 0.531 | 1 | 0.499 | 1.629 |

| Age | 0.128 | 0.388 | 0.001 | 1.117 | 0.412 | 1.881 |

| Obesity | 0.115 | 0.328 | 0.006 | 1.191 | 0.469 | 1.695 |

| Diabetes | 0.178 | 0.363 | 0.001 | 1.249 | 1.596 | 6.616 |

| Renal disease | 0.281 | 0.376 | 0.005 | 1.325 | 0.634 | 2.771 |

| DD | 0.231 | 0.411 | 0.003 | 1.426 | 1.532 | 7.662 |

| GLS | 0.491 | 0.390 | 0.008 | 1.634 | 0.761 | 3.509 |

| LA strain | 1.115 | 0.365 | 0.001 | 2.238 | 1.584 | 6.620 |

| HM | 1.023 | 0. 401 | 0.001 | 1.471 | 1.459 | 4.456 |

| Homocysteine | 0.067 | 0.356 | 0.002 | 1.936 | 0.465 | 1.881 |

| PON1 | 0.144 | 0.304 | 0.006 | 1.155 | 0.636 | 2.096 |

| Constant | −1.6 | 0.438 | 0.000 | 0 | - | - |

| Model | AUC-ROC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | 0.78 (0.72–0.83) | 72 | 70 | 71 | Reference |

| Random forest | 0.86 (0.81–0.90) | 80 | 78 | 79 | 0.01 |

| XGBoost | 0.88 (0.83–0.92) | 82 | 80 | 81 | 0.005 |

| * | C | P1 | P2 | P3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♀ | ♂ | ♀ | ♂ | ♀ | ♂ | ♀ | ♂ | |

| PulsIn | 11.7 ± 9.48 | 17.34 ± 12.3 | 18 ± 1.5 | 43 ± 9.7 | 26.69 ± 9.21 | 41 ± 9.2 | 34.53 ± 8.27 | 44.11 ± 9.68 |

| Framingham | 4.21 ± 3.4 | 9.09 ± 7.76 | 26.65 ± 6.97 | 33.5 ± 7.22 | 19.07 ± 6.75 | 26.18 ± 8.16 | 19.53 ± 2.04 | 25.2 ± 5.95 |

| Qrisk 2 | 7.34 ± 5.92 | 14.1 ± 9.01 | 33.71 ± 8.82 | 40.1 ± 7.5 | 24.82 ± 8.63 | 33.2 ± 8.7 | 26.04 ± 3.97 | 32.55 ± 8.05 |

| Score2 & Score2 OP | 5.83 ± 4.7 | 7.76 ± 4.21 | 13.9 ± 7.38 | 15.9 ± 7.56 | 14.98 ± 3.47 | 20.3 ± 3.45 | 24.93 ± 3.67 | 22.1 ± 2.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Popa, C.D.; Dan, R.; Haidar, I.; Popescu, C.; Dan, R.; Popa, T.; Petrescu, L. Quantification of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Hypertensive Subjects in Active Romanian Population Using New Echocardiographic, Biological and Atherogenic Markers. Medicina 2026, 62, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010032

Popa CD, Dan R, Haidar I, Popescu C, Dan R, Popa T, Petrescu L. Quantification of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Hypertensive Subjects in Active Romanian Population Using New Echocardiographic, Biological and Atherogenic Markers. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010032

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Calin Daniel, Rodica Dan, Iosef Haidar, Cristina Popescu, Roxana Dan, Tabita Popa, and Lucian Petrescu. 2026. "Quantification of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Hypertensive Subjects in Active Romanian Population Using New Echocardiographic, Biological and Atherogenic Markers" Medicina 62, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010032

APA StylePopa, C. D., Dan, R., Haidar, I., Popescu, C., Dan, R., Popa, T., & Petrescu, L. (2026). Quantification of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Hypertensive Subjects in Active Romanian Population Using New Echocardiographic, Biological and Atherogenic Markers. Medicina, 62(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010032