The Microbiological Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance in Acute Acalculous and Calculous Cholecystitis: A Seven-Year Study in a Tertiary Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

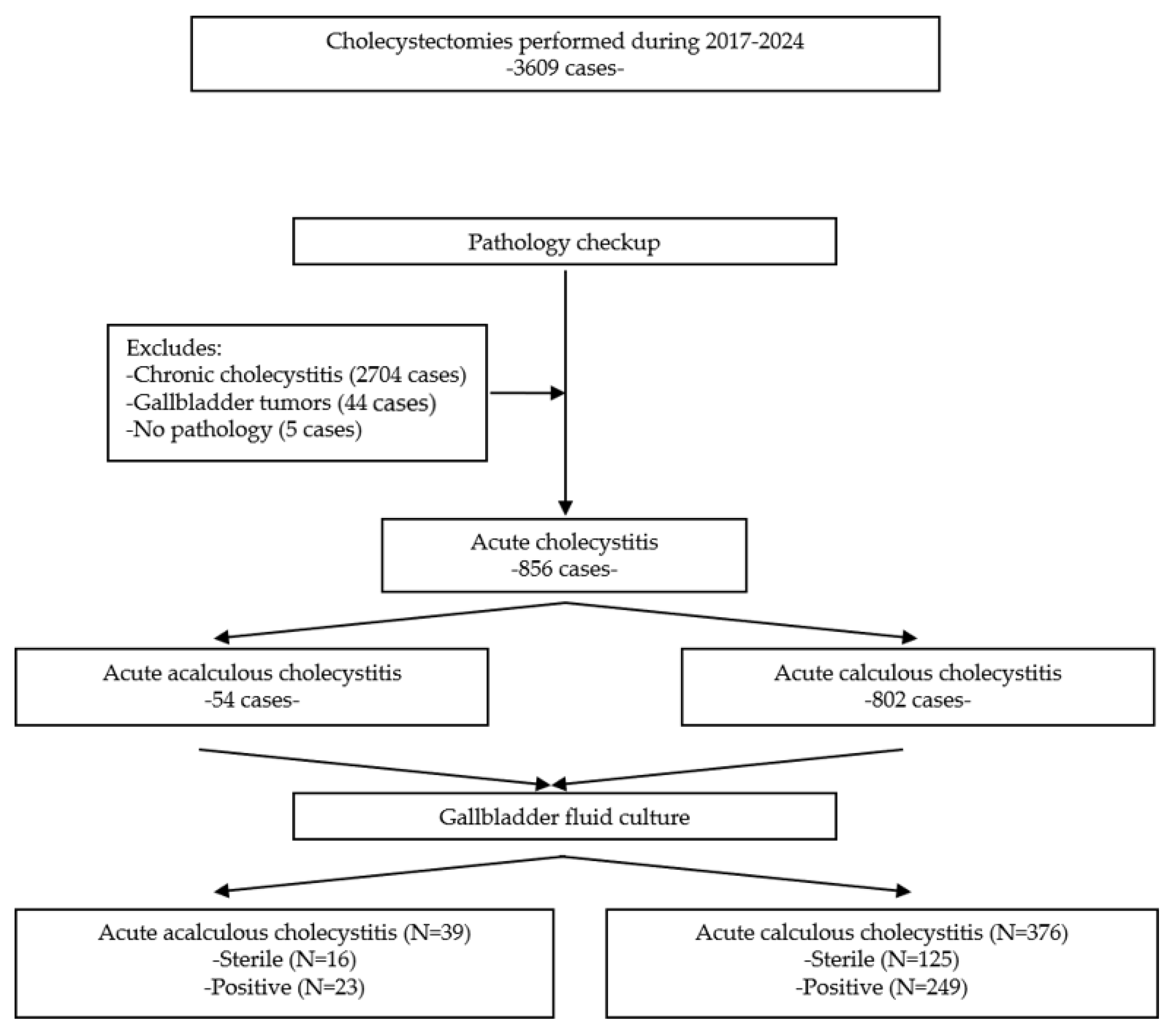

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Materials and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Study Approval

2.4. Statistical Analysis

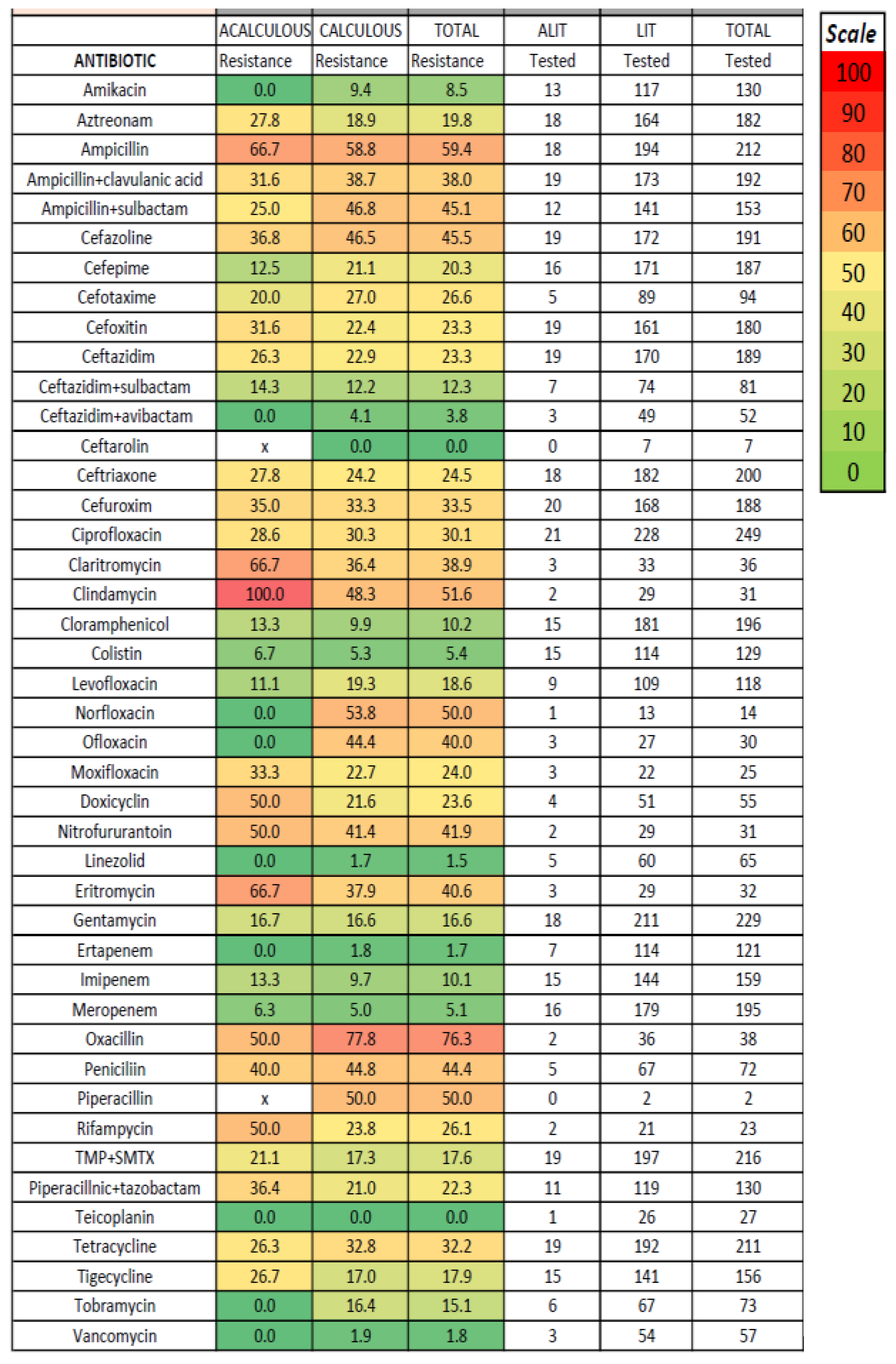

3. Results

Characteristics of the Included Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAC | Acalculous acute cholecystitis |

| AIDS | Directory of open access journals |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

| VRE | Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci |

References

- Gomi, H.; Solomkin, J.S.; Schlossberg, D.; Okamoto, K.; Takada, T.; Strasberg, S.M.; Ukai, T.; Endo, I.; Iwashita, Y.; Hibi, T.; et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.C.; Duan, H.L.; Ma, X. Unseen crisis: Point-of-care ultrasound detection of minute gallbladder perforation in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Asian J. Surg. 2024, 48, 2328–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganpathi, I.S.; Diddapur, R.K.; Eugene, H.; Karim, M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: Challenging the myths. HPB 2007, 9, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castana, O.; Rempelos, G.; Anagiotos, G.; Fonia, E.; Kiskira, O. Acute acalculous cholecystitis—A rare complication of burn injury. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2009, 22, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hariz, A.; Beji, I.; Hamdi, M.S.; Cherif, E. Brucellosis, an uncommon cause of acute acalculous cholecystitis: Two new cases and concise review. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e229616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.F.; Palisoc, K.; Pinto, C.N.; Lease, J.A.; Baghli, S. Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Acalculous Cholecystitis and Review of the Literature. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 18, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaak, J.S. Epstein-Barr virus acute acalculous cholecystitis. CMAJ 2021, 193, E1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.Y.; Hsu, F.C.; Wang, S.C.; Hsu, K.F. Acute acalculous cholecystitis following revisional laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for gastric clipping: A case report. Asian J. Surg. 2021, 44, 1434–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Introno, A.; Gatti, P.; Manca, G.; D’Amuri, A.; Minniti, S.; Ciracì, E. Acute acalculous cholecystitis as an early manifestation of COVID-19: Case report and literature review. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93 (Suppl. S1), e2022207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragò, M.; Fiore, D.; De Rosa, S.; Amaddeo, A.; Pulitanò, L.; Bozzarello, C.; Iannello, A.M.; Sammarco, G.; Indolfi, C.; Rizzuto, A. Acute acalculous cholecystitis and cardiovascular disease, which came first? After two hundred years still the classic chicken and eggs debate: A review of literature. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 78, 103668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markaki, I.; Konsoula, A.; Markaki, L.; Spernovasilis, N.; Papadakis, M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis due to infectious causes. World J. Clin. Cases. 2021, 9, 6674–6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Pang, L.; Dai, W.; Wu, S.; Kong, J. Advances in the Study of Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis: A Comprehensive Review. Dig. Dis. 2022, 40, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, Y. Acute acalculous cholecystitis as the initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematous: A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, e26238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boninsegna, S.; Storato, S.; Riccardi, N.; Soprana, M.; Oliboni, E.; Tamarozzi, F.; Bocus, P.; Martini, M.; Floreani, A. Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) acute acalculous cholecystitis in an immunocompromised adult patient: A case report and a literature review of a neglected clinical presentation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E237–E242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiakalos, A.; Schinas, G.; Karatzaferis, A.; Rigopoulos, E.A.; Pappas, C.; Polyzou, E.; Dimopoulou, E.; Dimopoulos, G.; Akinosoglou, K. Acalculous Cholecystitis as a Complication of Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infection: A Case-Based Scoping Review of the Literature. Viruses 2024, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awan, J.R.; Akhtar, Z.; Inayat, F.; Farooq, A.; Goraya, M.H.N.; Ishtiaq, R.; Malik, S.; Younus, F.; Kazmi, S.; Ashraf, M.J.; et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis as a rare gastroenterological association of COVID-19: A case series and systematic review. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2023, 9, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Thomaidou, E.; Karlafti, E.; Didagelos, M.; Megari, K.; Argiriadou, E.; Akinosoglou, K.; Paramythiotis, D.; Savopoulos, C. Acalculous Cholecystitis in COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Gu, M.G.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, T.N. Long-term outcomes of acute acalculous cholecystitis treated by non-surgical management. Medicine 2020, 99, e19057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.Q.; Chen, G.D.; Xie, F.; Li, X.; Mao, X.; Jia, B. Percutaneous cholecystostomy as a definitive treatment for moderate and severe acute acalculous cholecystitis: A retrospective observational study. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groszman, L.; Hopkins, B.; AlShahwan, N.; Fraser, S.; Bergman, S.; Pelletier, J.S.; Vanounou, T.; Wong, E.G. Predicting Acute Cholecystitis on Final Pathology to Prioritize Surgical Urgency: An Evaluation of the Tokyo Criteria and Development of a Novel Predictive Score. J. Surg. Res. 2025, 314, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Farshchian, J.N.; Hus, N. A Retrospective Study Comparing Radiological to Histopathological Diagnosis After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Suspected Cholecystitis. Cureus 2020, 12, e10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Takada, T.; Kawarada, Y.; Nimura, Y.; Hirata, K.; Sekimoto, M.; Yoshida, M.; Mayumi, T.; Wada, K.; Miura, F.; et al. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2007, 14, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Castillo, A.M.; Sancho-Insenser, J.; De Miguel-Palacio, M.; Morera-Casaponsa, J.R.; Membrilla-Fernández, E.; Pons-Fragero, M.J.; Pera-Román, M.; Grande-Posa, L. Mortality risk estimation in acute calculous cholecystitis: Beyond the Tokyo Guidelines. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartín, A.; González, M.; Muriel, P.; Cuello, E.; Pinillos, A.; Santamaría, M.; Salvador, H.; Olsina, J.J. Litiasic acute cholecystitis: Application of Tokyo Guidelines in severity grading. Cir. Cir. 2021, 89, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, J.M.; Livermore, D.M.; Nicolau, D.P. The difficulties of identifying and treating Enterobacterales with OXA-48-like carbapenemases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F.; Sartelli, M.; Catena, F.; Montori, G.; Di Saverio, S.; Sugrue, M.; Ceresoli, M.; Manfredi, R.; Ansaloni, L.; CIAO and CIAOW Study Groups. Antibiotic resistance pattern and clinical outcomes in acute cholecystitis: 567 consecutive worldwide patients in a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 21, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.P.; Seo, H.I. Clinical aspects of bile culture in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine 2018, 97, e11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafagh, S.; Rohani, S.H.; Hajian, A. Biliary infection; distribution of species and antibiogram study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 70, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašić, F.; Delibegović, S. The use of microbiological and laboratory data in the choice of empirical antibiotic therapy in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy—The role of local antibiograms. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Kang, J.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Byun, Y.; Jin, S.H.; Yoon, K.C.; Lee, H.W.; Jang, J.Y.; Lim, C.S. Suggested use of empirical antibiotics in acute cholecystitis based on bile microbiology and antibiotic susceptibility. HPB 2023, 25, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, U.; Handler, C.; Chazan, B.; Weiner, N.; Hatoum, O.A.; Yanovskay, A.; Kopelman, D. The Bacteriology of Acute Cholecystitis: Comparison of Bile Cultures and Clinical Outcomes in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.Y.; Do, J.H.; Oh, H.C.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, S.E.; Kang, H.; Hong, S.A. Relationship between the Tokyo Guidelines and Pathological Severity in Acute Cholecystitis. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, H.; Takada, T.; Hwang, T.L.; Akazawa, K.; Mori, R.; Endo, I.; Miura, F.; Kiriyama, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Itoi, T.; et al. Updated comprehensive epidemiology, microbiology, and outcomes among patients with acute cholangitis. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2017, 24, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, M.; Inagaki, M.; Omoto, K.; Onoda, N.; Kitada, K.; Tokunaga, N.; Yunoki, K.; Okabayashi, H.; Hamano, R.; Miyaso, H.; et al. Clinical impact of bile culture from gallbladder in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Surg. Today 2025, 55, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.W.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, S.H.; Do, J.H.; Oh, H.C.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.E. Antibiotic selection based on microbiology and resistance profiles of bile from gallbladder of patients with acute cholecystitis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Akada, M.; Shimizu, K.; Nishida, Y.; Izai, J.; Kajioka, H.; Miura, T.; Ishida, M.; Unno, M. Current status and therapeutic strategy of acute acalculous cholecystitis: Japanese nationwide survey in the era of the Tokyo guidelines. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2024, 31, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvellas, C.J.; Dong, V.; Abraldes, J.G.; Lester, E.L.; Kumar, A. The impact of delayed source control and antimicrobial therapy in 196 patients with cholecystitis-associated septic shock: A cohort analysis. Can. J. Surg. 2019, 62, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, V.; La Greca, A.; Tropeano, G.; Di Grezia, M.; Chiarello, M.M.; Brisinda, G.; Sganga, G. Updates on Antibiotic Regimens in Acute Cholecystitis. Medicina 2024, 60, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakuş, Ü.; Peker, Y.S. Is combined rather than single antibiotic therapy actually reasonable in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2021, 67, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miguel-Palacio, M.; González-Castillo, A.M.; Membrilla-Fernández, E.; Pons-Fragero, M.J.; Pelegrina-Manzano, A.; Grande-Posa, L.; Morera-Casaponsa, R.; Sancho-Insenser, J.J. Impact of empiric antibiotic therapy on the clinical outcome of acute calculous cholecystitis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, D.; Cossé, C.; Régimbeau, J.M. Antibiotic therapy in acute calculous cholecystitis. J. Visc. Surg. 2013, 150, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiñanzas, C.; Tigera, T.; Ferrer, D.; Calvo, J.; Herrera, L.A.; Pajarón, M.; Gómez-Fleitas, M.; Fariñas, M.C. Papel de la bacteriobilia en las complicaciones postoperatorias [Role of bacteriobilia in postoperative complications]. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2016, 29, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.H.; Paik, K.Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Oh, J.S. Clinical implication of bactibilia in moderate to severe acute cholecystitis undergone cholecystostomy following cholecystectomy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, S.M.; Zlatian, O.M.; Plesea, E.L.; Vacariu, A.I.; Cimpoeru, M.; Rogoveanu, I.; Bigea, C.C.; Iordache, S. Predominant Gram-Positive Etiology May Be Associated with a Lower Mortality Rate but with Higher Antibiotic Resistance in Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis: A 7-Year Study in a Tertiary Center in Romania. Life 2025, 15, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miguel-Palacio, M.; González-Castillo, A.M.; Martín-Ramos, M.; Membrilla-Fernández, E.; Pelegrina-Manzano, A.; Pons-Fragero, M.J.; Grande-Posa, L.; Sancho-Insenser, J.J. Microbiological etiology and current resistance patterns in acute calculous cholecystitis. Cir. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 102, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitzan, O.; Brodsky, Y.; Edelstein, H.; Hershko, D.; Saliba, W.; Keness, Y.; Peretz, A.; Chazan, B. Microbiologic Data in Acute Cholecystitis: Ten Years’ Experience from Bile Cultures Obtained during Percutaneous Cholecystostomy. Surg. Infect. 2017, 18, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheeskaran, M.; Hussan, A.; Anto, A.; de Preux, L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis for acute cholecystectomy. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2023, 10, e001162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, T.; Tavakoli, K. Necrotizing Cholecystitis in the Gallbladder: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e21368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouriki, S.; Agapitou, T.; Tsagkaraki, A.; Manthou, P.; Tsikrikas, S.; Varvitsioti, D.; Kollia, T.; Kranidioti, H. An Acute Gangrenous Cholecystitis Caused by Candida auris: A Case From a Greek Hospital. Cureus 2024, 16, e71338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil Fortuño, M.; Granel Villach, L.; Sabater Vidal, S.; Soria Martín, R.; Martínez Ramos, D.; Escrig Sos, J.; Moreno Muñoz, R.; Igual Adell, R. Microbiota biliar en pacientes colecistectomizados: Revisión de la antibioterapia empírica [Biliary microbiote in cholecystectomized patients: Review of empirical antibiotherapy]. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2019, 32, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dyrhovden, R.; Øvrebø, K.K.; Nordahl, M.V.; Nygaard, R.M.; Ulvestad, E.; Kommedal, Ø. Bacteria and fungi in acute cholecystitis. A prospective study comparing next generation sequencing to culture. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Grade I (mild) | Acute cholecystitis with no criteria for grade II or III |

| Grade II (moderate) | Any of the following: |

| -white blood cells >18,000/mm3 | |

| -palpable soft mass in the right hypochondrium | |

| -symptoms for more than 72 h | |

| -marked local inflammation (gangrenous or emphysematous cholecystitis, peri-cholecystic or hepatic abscess, choleperitoneum) | |

| Grade III (severe) | Associated with organ/system dysfunction: |

| -hypotension requiring at least 5 µg/min dopamine or any epinephrine dose -decreased level of consciousness | |

| -PaO2/FiO2 < 300 | |

| -oliguria or creatinine level > 2 mg/dL | |

| -INR > 1.5 | |

| -platelet count < 100,000/mm3 |

| Grade I | Any deviation from the normal intraoperative or postoperative course, including the need for pharmacologic treatment other than antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics, electrolytes, or physiotherapy |

| Grade II | Complications needing only the use of intravenous medications, total intravenous nutrition, or blood transfusion |

| Grade III | Complications needing surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic intervention under local or general anesthesia |

| Grade IV | Life-threatening complications requiring ICU management—single or multiple organ dysfunction (including hemodialysis) |

| Grade V | Death |

| Acalculous Cholecystitis N = 54 | Calculous Cholecystitis N = 802 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: yrs Mean ± Std (Min-Max) | 66.6 ± 13.2 (19–88) | 61.4 ± 15.6 (18–96) | 0.014 |

| Gender M/F (No, % of females) | 31/23 (42.6) | 455/347 (56.7) | 0.043 |

| Tokyo classification | 0.005 | ||

| -I | 14 (25.9) | 321 (40.0) | |

| -II | 33 (61.1) | 446 (55.6) | |

| -III | 7 (13.0) | 35 (4.4) | |

| Complications (%) | |||

| -gangrenous | 27 (50) | 318 (39.7) | 0.136 |

| -phlegmonous | 16 (29.6) | 127 (15.8) | 0.010 |

| -perforation | 18 (33.3) | 155 (19.3) | 0.013 |

| -fistula | 1 (1.9) | 12 (1.5) | 0.836 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| -obesity | 13 (24.1) | 235 (29.3) | 0.412 |

| -hypertension | 29 (53.7) | 416 (51.9) | 0.794 |

| -cardiovascular diseases | 35 (64.8) | 449 (56.0) | 0.205 |

| -respiratory diseases | 5 (5.1) | 41 (9.3) | 0.191 |

| -liver cirrhosis | 1 (1.9) | 11 (1.4) | 0.771 |

| -peptic ulcer | 1 (1.9) | 5 (0.6) | 0.295 |

| -diabetes | 19 (35.2) | 168 (20.9) | 0.014 |

| -renal diseases | 1 (1.9) | 19 (2.4) | 0.808 |

| -neurological diseases | 6 (11.1) | 40 (5) | 0.053 |

| -tumors | 1 (1.9) | 17 (2.1) | 0.894 |

| -COVID-19 infection | 1 (1.9) | 9 (1.1) | 0.629 |

| -Clostridium difficile infection | 2 (3.7) | 6 (0.7) | 0.029 |

| -rheumatological diseases | 0 (0) | 3 (0.4) | 0.653 |

| Laboratory | |||

| -Hb (g/dL) | 12.3 ± 1.8 | 13 ± 1.8 | 0.002 |

| -leucocyte count | 13,756 ± 6571 | 13,079 ± 6498 | 0.562 |

| -neutrophil count | 11,630 ± 6261 | 10,228 ± 6302 | 0.083 |

| -lymphocyte count | 1165 ± 662 | 1701 ± 898 | <0.001 |

| -platelet count | 226,826 ± 92,327 | 256,164 ± 93,060 | 0.025 |

| -urea (mg/dL) | 75 ± 61 | 44 ± 25 | <0.001 |

| -creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.59 ± 1.65 | 1.01 ± 0.74 | <0.001 |

| -serum glucose (mg/dL) | 134 ± 66 | 120 ± 56 | 0.129 |

| -ALT (IU/L) | 110 ± 145 | 68 ± 118 | <0.001 |

| -AST (IU/L) | 109 ± 137 | 57 ± 99 | <0.001 |

| -serum amylase (IU/L) | 103 ± 167 | 87 ± 244 | 0.482 |

| -total bilirubin (mg/dL)) | 2.25 ± 2.82 | 1.31 ± 1.80 | 0.014 |

| -direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.37 ± 2.08 | 0.70 ± 1.36 | 0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± standard deviation) | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 2.5 ± 2 | 0.002 |

| Surgery type | <0.001 | ||

| -laparoscopic | 23 (42.6) | 563 (70.2) | |

| -open | 26 (48.1) | 187 (23.3) | |

| -conversion | 5 (9.3) | 52 (6.5) | |

| Complications (Dindo–Clavien grade) | <0.001 | ||

| -0 | 39 (72.2) | 746 (93) | |

| -1/2 | 2 (3.7) | 12 (1.5) | |

| -3/4 | 3 (5.6) | 15 (1.8) | |

| Mean hospital stay (days) | 9.7 ± 5.6 | 8.4 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 10 (18.5) | 29 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Acalculous Cholecystitis N = 54 | Calculous Cholecystitis N = 802 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive patients | 23 (60.5) | 249 (66.2) | 0.3660 |

| Positive cultures | 33 (67.3) | 327 (71.7) | 0.5279 |

| Gram-negative | 28 (84.9) | 242 (74) | 0.1775 |

| -E. coli | 14 (42.4) | 117 (35.8) | 0.4992 |

| -Klebsiella | 9 (27.3) | 65 (19.9) | 0.2020 |

| -Enterobacter | 3 (9.1) | 19 (5.8) | 0.4759 |

| -Serratia | 2 (6.1) | 3 (0.9) | 0.0391 |

| -Pseudomonas | 0 (0) | 13 (4) | 0.4587 |

| -Proteus | 0 (0) | 7 (2.1) | 0.7502 |

| -Citrobacter | 0 (0) | 10 (3.1) | 0.5766 |

| -Acinetobacter | 0 (0) | 8 (2.4) | 0.5505 |

| Gram-positive | 5 (15.1) | 79 (24.2) | 0.9862 |

| -Enterococcus | 2 (6.1) | 46 (14.1) | 0.2020 |

| -Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (3) | 18 (5.5) | 0.5384 |

| -Staphylococcus coagulase-negative | 1 (3) | 3 (0.9) | 0.3058 |

| -Streptococcus | 1 (3) | 12 (3.7) | 0.8372 |

| Anaerobes | |||

| -Peptostreptococcus | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | 0.6789 |

| Candida spp. | 0 (0) | 4 (1.2) | 0.9725 |

| MDR (%) | XDR (%) | ESBL (%) | CPE (%) | MRSA (%) | VRE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All bacterial strains | 155/354 (43.8) | 6/354 (1.7) | - | - | - | - |

| Gram-negative | 10/268 (3.7) | 21/268 (7.8) | - | - | ||

| -E. coli | 55/131 (42) | 0/131 (0) | 3/131 (2.3) | 5/131 (4.1) | - | - |

| -Klebsiella | 40/74 (54.1) | 1/74 (1.4) | 6/74 (8.1) | 6/74 (8.1) | - | - |

| -Enterobacter | 14/22 (63.6) | 0/22 (0) | 1/22 (4.5) | 0/22 (0) | - | - |

| -Serratia | 3/11 (27.3) | 1/11 (9.1) | 0/11 (0) | 1/11 (9.1) | - | - |

| -Pseudomonas | 4/10 (40) | 0/10 (0) | 0/10 (0) | 4/10 (30.8) | - | - |

| -Proteus | 5/8 (62.5) | 3/8 (37.5) | 0/8 (0) | 0/8 (0) | - | - |

| -Citrobacter | 6/7 (85.7) | 0/7 (0) | 0/7 (0) | 2/7 (28.6) | - | - |

| -Acinetobacter | 5/5 (100) | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 3/5 (60) | - | - |

| Gram-positive | ||||||

| -Enterococcus | 5/48 (10.4) | 0/48 (0) | - | - | - | 1/48 (2) |

| -Staphylococcus aureus | 13/18 (72.2) | 1/18 (5.6) | - | - | 11/18 (61.1) | - |

| -Staphylococcus coagulase-negative | 4/5 (80) | 0/5 (0) | - | - | 0/5 (0) | - |

| -Streptococcus | 0/13 (0) | 0/13 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Anaerobes | - | - | - | - | ||

| -Peptostreptococcus | 1/2 (50) | 0/2 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Factor | Univariate Analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI), p | Multivariate Analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI), p |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥60/<60 years | 55.489 (3.399–906), 0.005 | 69.392 (4.268–1128.209), 0.003 (0.24 to 25.7) |

| Tokyo grade | ||

| -Grade III vs. I | 91.420 (25.192–331.753), <0.001 | 5.126 (1.835–14.325), 0.002 |

| -Grade II vs. I | 4.072 (1.183–14.008), 0.026 | 3.609 (0.687–6.320), 0.067 |

| Renal injury | 15.220 (7.616–30.414), <0.001 | 4.974 (2.335–10.597), <0.001 |

| Acalculous cholecystitis | 6.058 (2.776–13.220), <0.001 | 2.164 (0.961–4.872), 0.062 |

| Open cholecystectomy | 21.670 (7.617 to 61.649), <0.001 | 7.807 (3.365–18.112), <0.001 |

| Perforation | 2.607 (1.336 to 5.085), 0.005 | 1.920 (0.971–3.799), 0.061 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obleaga, C.V.; Zlatian, O.M.; Cristea, O.M.; Rosu-Pires, A.; Pascu, A.M.; Florescu, M.-M.; Ionele, C.M.; Rogoveanu, I.; Popescu, A.V.; Catanoiu, V.; et al. The Microbiological Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance in Acute Acalculous and Calculous Cholecystitis: A Seven-Year Study in a Tertiary Center. Medicina 2025, 61, 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112028

Obleaga CV, Zlatian OM, Cristea OM, Rosu-Pires A, Pascu AM, Florescu M-M, Ionele CM, Rogoveanu I, Popescu AV, Catanoiu V, et al. The Microbiological Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance in Acute Acalculous and Calculous Cholecystitis: A Seven-Year Study in a Tertiary Center. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112028

Chicago/Turabian StyleObleaga, Cosmin Vasile, Ovidiu Mircea Zlatian, Oana Mariana Cristea, Alexandra Rosu-Pires, Alexandru Marin Pascu, Mirela-Marinela Florescu, Claudiu Marinel Ionele, Ion Rogoveanu, Alexandru Valentin Popescu, Vlad Catanoiu, and et al. 2025. "The Microbiological Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance in Acute Acalculous and Calculous Cholecystitis: A Seven-Year Study in a Tertiary Center" Medicina 61, no. 11: 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112028

APA StyleObleaga, C. V., Zlatian, O. M., Cristea, O. M., Rosu-Pires, A., Pascu, A. M., Florescu, M.-M., Ionele, C. M., Rogoveanu, I., Popescu, A. V., Catanoiu, V., & Cazacu, S. M. (2025). The Microbiological Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance in Acute Acalculous and Calculous Cholecystitis: A Seven-Year Study in a Tertiary Center. Medicina, 61(11), 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112028