Digital Healthcare Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Hospital and Long-Term Care Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

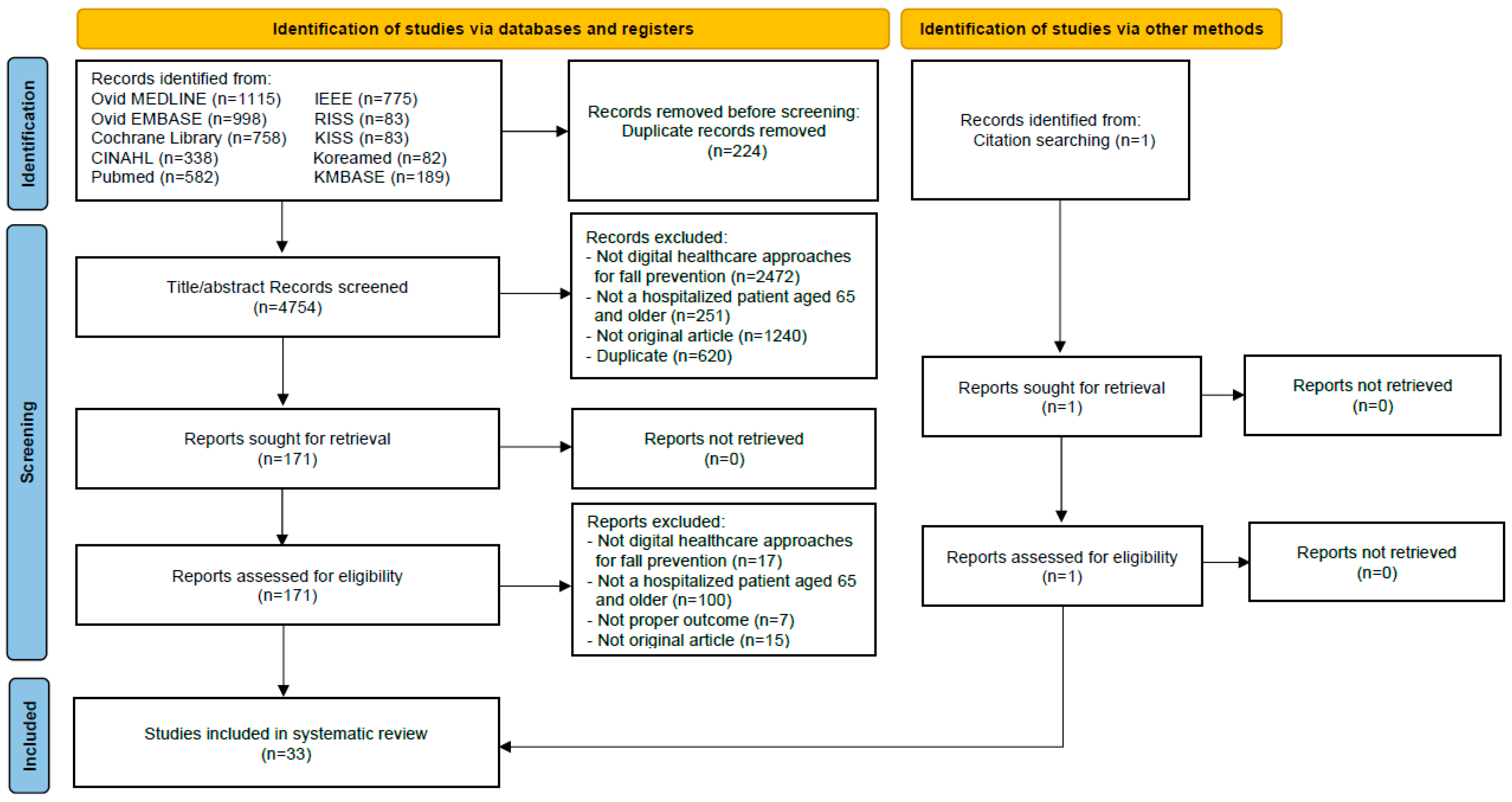

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Trials

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Characteristics of Digital Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction

3.4.1. Fall Detection Systems

3.4.2. Fall Prediction Models

| Authors (Year) | Country | Type of Facility | Study Design | Duration | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size (I/C) | Mean Age (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall Detection (n = 20) | |||||||

| Can et al. (2024) [13] | Turkey | LTCF | Quasi-experimental | 3 months |

| 13/13 | I: 82.7 ± 10.1 C: 81.9 ± 9.3 |

| Dollard et al. (2022) [27] | Australia | Hospital | Mixed methods | 23 months |

| 88 | 83.0 ± 9.0 |

| Pham et al. (2022) [28] | Australia | Hospital | Quasi-experimental | 5 years |

| 997/663 | I: 85.3 ± 7.7 C: 85.8 ± 7.7 |

| Saleh et al. (2021) [43] | France | LTCF | Prospective observational | 13 months |

| 16 | 80 years or older |

| Visvanathan et al. (2022) [30] | Australia | Hospital | RCT | 2 years |

| 1244/1995 | I: 84.0 ± 7.9 C: 81.9 ± 8.3 |

| Borda et al. (2018) [37] | Australia | LTCF | Prospective observational | 1 month |

| 4 | 87.0 |

| White et al. (2018) [44] | USA | LTCF | Retrospective observational | 5 months |

| 80/80 | 65–95 (range) |

| Gattinger et al. (2017) [39] | Switzerland | LTCF | RCT | 11 months |

| 22/22 | I: 86.4 ± 8.6 C: 88.7 ± 5.2 |

| Shinmoto Torres et al. (2017) [29] | Australia | Hospital | Quasi-experimental | 20–25 min |

| 26 | 71–93 (range) |

| Subermaniam et al. (2016) [34] | Malaysia | Hospital | Quasi-experimental | 2 months |

| 31 | 83.0 ± 7.0 |

| Lipsitz et al. (2016) [42] | USA | LTCF | Prospective observational | 6 months |

| 62 | 86.2 ± 8.1 |

| Abbate et al. (2014) [36] | Canada | LTCF | Prospective observational | 1 month |

| 4 | 75–92 |

| Wong Shee et al. (2014) [33] | Australia | Hospital | Quasi-experimental | 6 months |

| 34 | 85.2 ± 7.7 |

| Sahota et al. (2014) [32] | UK | Hospital | RCT | 27 months |

| 918/921 | 84.6 |

| Wolf et al. (2013) [31] | Germany | Hospital | RCT | 13 months |

| 48/50 | Not specified |

| Bloch et al. (2011) [26] | France | Hospital | Prospective observational | 22 months |

| 10 | 83.4 ± 7.5 |

| Capezuti et al. (2009) [38] | USA | LTCF | Prospective observational | 8 months |

| 14 | 80.4 ± 5.9 |

| Holmes et al. (2007) [40] | USA | LTCF | Quasi-experimental | 15 months |

| 38/70 | I: 87.4 ± 7.0 C: 87.6 ± 7.5 |

| Kelly et al. (2002) [41] | USA | LTCF | Quasi-experimental | 5 months |

| 47 | 81.0 ± 7.0 |

| Tideiksaar et al. (1993) [35] | USA | Hospital | RCT | 9 months |

| 35/35 | 84 (67–97) |

| Fall Prediction (n = 13) | |||||||

| Shao et al. (2024) [55] | China | LTCF | Prospective observational | 6 months |

| 864 | 84.0 |

| Adeli et al. (2023) [12] | Canada | Hospital | Prospective observational | 22 months |

| 54 | 76.4 ± 7.9 |

| Millet et al. (2023) [48] | Spain | Hospital | Retrospective observational | 5 years |

| 304 | 80.3 ± 7.7 |

| Boyce et al. (2022) [54] | USA | LTCF | Retrospective observational | 6 years |

| 3985 | 77.0 |

| Chu et al. (2022) [47] | Taiwan | Hospital | Retrospective observational | 2 years |

| 1101 | 86.1 |

| Song et al. (2022) [45] | China | Hospital | Prospective observational | Not stated |

| 48 | LR: 72.3 ± 6.0 HR: 75.9 ± 6.9 |

| Mehdizadeh et al. (2021) [50] | Canada | Hospital | Prospective observational | 2 weeks +follow up 30 days |

| 51 | 76.3 ± 7.9 |

| Unger et al. (2021) [53] | Germany | LTCF | Prospective observational | 1 year |

| 22 | 88.2 (78–99) |

| Buisseret et al. (2020) [51] | Belgium | LTCF | Prospective observational | 6 months |

| 73 | 83.0 ± 8.3 |

| Suzuki et al. (2020) [56] | Japan | LTCF | Prospective observational | 9 months |

| 42 | 85.7 ± 5.6 |

| Beauchet et al. (2018) [46] | France | Hospital | Prospective observational | 6 months |

| 848 | 83.0 ± 7.2 |

| Gietzelt et al. (2014) [52] | Germany | LTCF | Prospective observational | 11 months |

| 40 | 76.0 ± 8.3 |

| Marschollek et al. (2011) [49] | Germany | Hospital | Prospective observational | 18 months |

| 46 | 81.3 |

3.5. Effectiveness of Digital Approaches for Fall Prevention

3.5.1. Fall Detection Systems

3.5.2. Fall Prediction Models

Short-Term Prediction Models (<1 Month)

Long-Term Prediction Models (>3 Months)

4. Discussion

4.1. Domains of Digital Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction

4.2. Comparative Effectiveness and Clinical Implications

4.2.1. Fall Detection Systems

4.2.2. Fall Prediction Models

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Falls. Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- LeLaurin, J.H.; Shorr, R.I. Preventing falls in hospitalized patients: State of the science. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 35, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.J.; Meng, Q.; Su, C.H. Mechanism-driven strategies for reducing fall risk in the elderly: A multidisciplinary review of exercise interventions. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, S.; Brau, F.; Galluzzo, V.; Santagada, D.A.; Loreti, C.; Biscotti, L.; Laudisio, A.; Zuccalà, G.; Bernabei, R. Falls among older adults: Screening, identification, rehabilitation, and management. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Si, W.; Pi, H. Incidence and risk factors related to fear of falling during the first mobilisation after total knee arthroplasty among older patients with knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2665–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, C.S.; Bergen, G.; Atherly, A.; Burns, E.; Stevens, J.; Drake, C. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Pecanac, K.; Krupp, A.; Liebzeit, D.; Mahoney, J. Impact of fall prevention on nurses and care of fall risk patients. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locklear, T.; Kontos, J.; Brock, C.A.; Holland, A.B.; Hemsath, R.; Deal, A.; Leonard, S.; Steinmetz, C.; Biswas, S. Inpatient falls: Epidemiology, risk assessment, and prevention measures. A narrative review. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2024, 5, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Seo, B.-J.; Kim, M.-Y. Time-varying hazard of patient falls in hospital: A retrospective case–control study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, O.L.; Vásquez, S.M.; Mendoza, A.C. Validation of the stratify scale for the prediction of falls among hospitalized adults in a tertiary hospital in Colombia: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleníková, R.; Jarošová, D. The predictive validity of the Morse Fall Scale in hospitalized patients in the Czech Republic. Nurs. 21st Century 2024, 23, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, V.; Korhani, N.; Sabo, A.; Mehdizadeh, S.; Mansfield, A.; Flint, A.; Iaboni, A.; Taati, B. Ambient monitoring of gait and machine learning models for dynamic and short-term falls risk assessment in people with dementia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 3599–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, B.; Tufan, A.; Karadağ, Ş.; DurmuŞ, N.; Topçu, M.; Aysevinç, B.; Düzel, S.; Dağcıoğlu, S.; AfŞar Fak, N.; Tazegül, G.; et al. The effectiveness of a fall detection device in older nursing home residents: A pilot study. Psychogeriatrics 2024, 24, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Yu, J.Y.; Jekal, S.; Song, Y.J.; Moon, K.T.; Lee, J.H.; Yeom, K.M.; Park, S.H.; Cho, I.S.; Song, M.R.; et al. Development and validation of interpretable machine learning models for inpatient fall events and electronic medical record integration. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2022, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Serhal, E. Digital health equity and COVID-19: The innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Su, J.; Ren, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H. Risk prediction models for falls in hospitalized older patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Riaz, M.H.; Wajid, H.; Saqib, M.; Zeeshan, M.H.; Khan, S.E.; Chauhan, Y.R.; Sohail, H.; Vohra, L.I. Current challenges and potential solutions to the use of digital health technologies in evidence generation: A narrative review. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1203945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.Y.; Chan, L.K.M.; Kuang, Y.M.; Le, M.N.V.; Celler, B. Digital care technologies in people with dementia living in long-term care facilities to prevent falls and manage behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.E.; Webster, K.; Jones, C.; Hill, A.M.; Haines, T.; McPhail, S.; Kiegaldie, D.; Slade, S.; Jazayeri, D.; Heng, H.; et al. Interventions to reduce falls in hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemyng, E.; Moore, T.H.; Boutron, I.; Higgins, J.P.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Nejstgaard, C.H.; Dwan, K. Using Risk of Bias 2 to assess results from randomised controlled trials: Guidance from Cochrane. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Regist. Copyr. 2018, 1148552, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Quadas-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, R.F.; Moons, K.G.; Riley, R.D.; Whiting, P.F.; Westwood, M.; Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Kleijnen, J.; Mallett, S.; Probast Group. PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F.; Gautier, V.; Noury, N.; Lundy, J.E.; Poujaud, J.; Claessens, Y.E.; Rigaud, A.S. Evaluation under real-life conditions of a stand-alone fall detector for the elderly subjects. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 54, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, J.; Hill, K.D.; Wilson, A.; Ranasinghe, D.C.; Lange, K.; Jones, K.; Boyle, E.M.; Zhou, M.; Ng, N.; Visvanathan, R. Patient acceptability of a novel technological solution (ambient intelligent geriatric management system) to prevent falls in geriatric and general medicine wards: A mixed-methods study. Gerontology 2022, 68, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.T.; Visvanathan, R.; Strong, M.; Wilson, E.C.F.; Lange, K.; Dollard, J.; Ranasinghe, D.; Hill, K.; Wilson, A.; Karnon, J. Cost-effectiveness and value of information analysis of an ambient intelligent geriatric management (AmbIGeM) system compared to usual care to prevent falls in older people in hospitals. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2023, 21, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinmoto Torres, R.L.; Visvanathan, R.; Abbott, D.; Hill, K.D.; Ranasinghe, D.C. A battery-less and wireless wearable sensor system for identifying bed and chair exits in a pilot trial in hospitalized older people. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, R.; Ranasinghe, D.C.; Lange, K.; Wilson, A.; Dollard, J.; Boyle, E.; Jones, K.; Chesser, M.; Ingram, K.; Hoskins, S.; et al. Effectiveness of the wearable sensor-based ambient intelligent geriatric management (AmbIGeM) system in preventing falls in older people in hospitals. J. Gerontol. A Biol. 2022, 77, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.H.; Hetzer, K.; zu Schwabedissen, H.M.; Wiese, B.; Marschollek, M. Development and pilot study of a bed-exit alarm based on a body-worn accelerometer. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 46, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahota, O.; Drummond, A.; Kendrick, D.; Grainge, M.J.; Vass, C.; Sach, T.; Gladman, J.; Avis, M. REFINE (REducing Falls in In-patieNt Elderly) using bed and bedside chair pressure sensors linked to radio-pagers in acute hospital care: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong Shee, A.; Phillips, B.; Hill, K.; Dodd, K. Feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of an electronic sensor bed/chair alarm in reducing falls in patients with cognitive impairment in a subacute ward. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2014, 29, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subermaniam, K.; Welfred, R.; Subramanian, P.; Chinna, K.; Ibrahim, F.; Mohktar, M.S.; Tan, M.P. The effectiveness of a wireless modular bed absence sensor device for fall prevention among older inpatients. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tideiksaar, R.; Feiner, C.F.; Maby, J. Falls prevention: The efficacy of a bed alarm system in an acute-care setting. Mt. Sinai J. Med. N. Y. 1993, 60, 522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Abbate, S.; Avvenuti, M.; Light, J. Usability study of a wireless monitoring system among alzheimer’s disease elderly population. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2014, 2014, 617495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Gilbert, C.; Said, C.; Smolenaers, F.; McGrath, M.; Gray, K. Non-contact sensor-based falls detection in residential aged care facilities: Developing a real-life picture. In Connecting the System to Enhance the Practitioner and Consumer Experience in Healthcare; Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 252, pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Capezuti, E.; Brush, B.L.; Lane, S.; Rabinowitz, H.U.; Secic, M. Bed-exit alarm effectiveness. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, H.; Hantikainen, V.; Ott, S.; Stark, M. Effectiveness of a mobility monitoring system included in the nursing care process in order to enhance the sleep quality of nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. Health Technol. 2017, 7, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.; Teresi, J.A.; Ramirez, M.; Ellis, J.; Eimicke, J.; Jian, K.; Orzechowska, L.; Silver, S. An evaluation of a monitoring system intervention: Falls, injuries, and affect in nursing homes. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2007, 16, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.E.; Phillips, C.L.; Cain, K.C.; Polissar, N.L.; Kelly, P.B. Evaluation of a nonintrusive monitor to reduce falls in nursing home patients. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2002, 3, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, L.A.; Tchalla, A.E.; Iloputaife, I.; Gagnon, M.; Dole, K.; Su, Z.Z.; Klickstein, L. Evaluation of an Automated Falls Detection Device in Nursing Home Residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Abbas, M.; Prud’Homm, J.; Somme, D.; Jeannes, R.L.B. A reliable fall detection system based on analyzing the physical activities of older adults living in long-term care facilities. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 2587–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Cuavers, K.Y. Do alarm devices reduce falls in the elderly population? J. Natl. Black Nurses Assoc. 2018, 29, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Ou, J.; Shu, L.; Hu, G.; Wu, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Z. Fall risk assessment for the elderly based on weak foot features of wearable plantar pressure. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Noublanche, F.; Simon, R.; Sekhon, H.; Chabot, J.; Levinoff, E.J.; Kabeshova, A.; Launay, C.P. Falls risk prediction for older inpatients in acute care medical wards: Is there an interest to combine an early nurse assessment and the artificial neural network analysis? J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.M.; Kristiani, E.; Wang, Y.C.; Lin, Y.R.; Lin, S.Y.; Chan, W.C.; Yang, C.T.; Tsan, Y.T. A model for predicting fall risks of hospitalized elderly in Taiwan-A machine learning approach based on both electronic health records and comprehensive geriatric assessment. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 937216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, A.; Madrid, A.; Alonso-Weber, J.M.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Perez-Rodra-Guez, R. Machine Learning techniques applied to the development of a fall risk index for older adults. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 84795–84809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschollek, M.; Rehwald, A.; Wolf, K.H.; Gietzelt, M.; Nemitz, G.; zu Schwabedissen, H.M.; Schulze, M. Sensors vs. experts-a performance comparison of sensor-based fall risk assessment vs. conventional assessment in a sample of geriatric patients. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2011, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, S.; Sabo, A.; Ng, K.D.; Mansfield, A.; Flint, A.J.; Taati, B.; Iaboni, A. Predicting short-term risk of falls in a high-risk group with dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 689–695.e681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisseret, F.; Catinus, L.; Grenard, R.; Jojczyk, L.; Fievez, D.; Barvaux, V.; Dierick, F. Timed up and go and six-minute walking tests with wearable inertial sensor: One step further for the prediction of the risk of fall in elderly nursing home people. Sensors 2020, 20, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietzelt, M.; Feldwieser, F.; Gövercin, M.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Marschollek, M. A prospective field study for sensor-based identification of fall risk in older people with dementia. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2014, 39, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, E.W.; Histing, T.; Rollmann, M.F.; Orth, M.; Herath, E.; Menger, M.; Herath, S.C.; Grimm, B.; Pohlemann, T.; Braun, B.J. Development of a dynamic fall risk profile in elderly nursing home residents: A free field gait analysis based study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 93, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, R.D.; Kravchenko, O.V.; Perera, S.; Karp, J.F.; Kane-Gill, S.L.; Reynolds, C.F.; Albert, S.M.; Handler, S.M. Falls prediction using the nursing home minimum dataset. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; Xiao, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.A.; Zhang, J.E. Development and external validation of a machine learning-based fall prediction model for nursing home residents: A prospective cohort study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Ishiguro, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Kotaki, H. Deep learning prediction of falls among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, O.L.; Piñeros, H.; Aya, P.A.; Sarmiento, J.; Arévalo, I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials: In-hospital use of sensors for prevention of falls. Medicine 2021, 100, e27467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.N.; Ribeiro, N.F.; Santos, C.P. Fall risk assessment using wearable sensors: A narrative review. Sensors 2022, 22, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani Hani, S.; Abu Aqoulah, E.A. Relationship between alarm fatigue and stress among acute care nurses: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241292584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Older adults (≥60 years) admitted to or residing in hospitals or LTCFs |

| Intervention | Digital healthcare approaches for fall detection and prevention (e.g., monitoring systems, sensors, ICT-based tools) |

| Comparison | Conventional strategies for fall detection and prevention without digital healthcare approaches |

| Outcomes | Fall-related outcomes (incidence, rate, injurious falls), device-related indicators (performance, cost), and user-centered outcomes (patient or caregiver satisfaction, usability, feasibility) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, A.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.-H. Digital Healthcare Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Hospital and Long-Term Care Settings. Medicina 2025, 61, 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111926

Lee A, Lee H, Lee S-H. Digital Healthcare Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Hospital and Long-Term Care Settings. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111926

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Aijin, Haneul Lee, and Seon-Heui Lee. 2025. "Digital Healthcare Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Hospital and Long-Term Care Settings" Medicina 61, no. 11: 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111926

APA StyleLee, A., Lee, H., & Lee, S.-H. (2025). Digital Healthcare Approaches for Fall Detection and Prediction in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Hospital and Long-Term Care Settings. Medicina, 61(11), 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111926