Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Vagal Schwannoma: Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

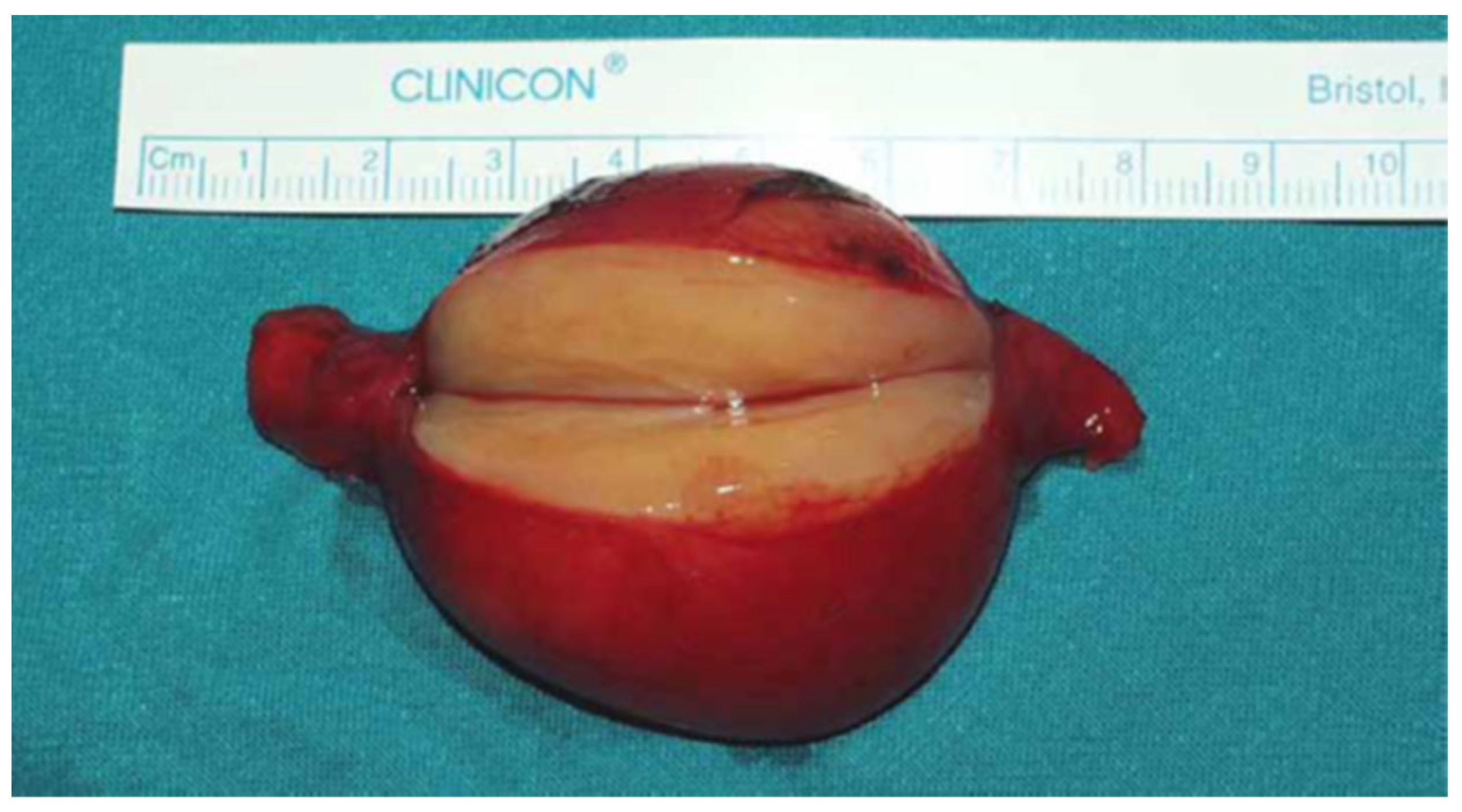

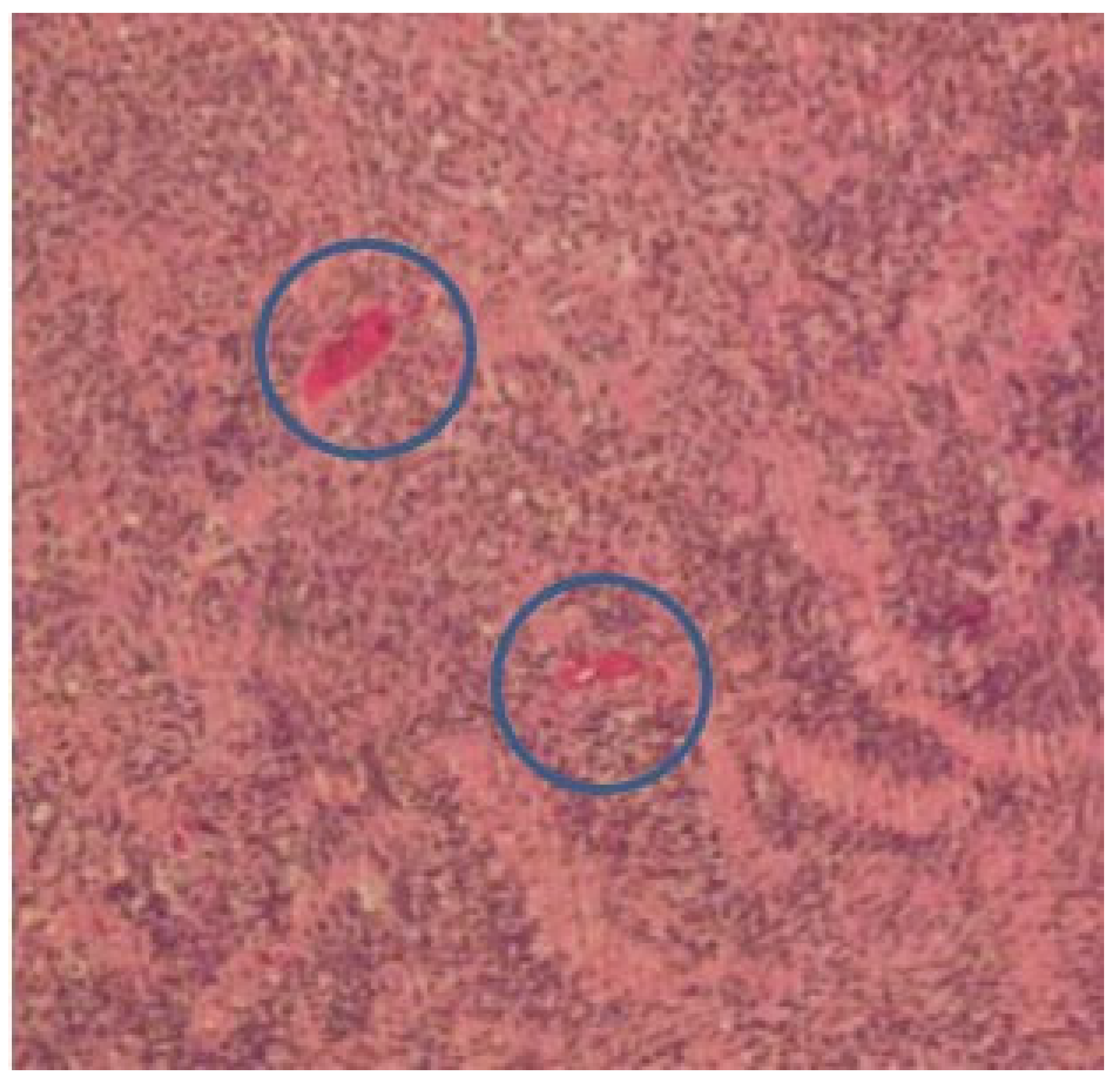

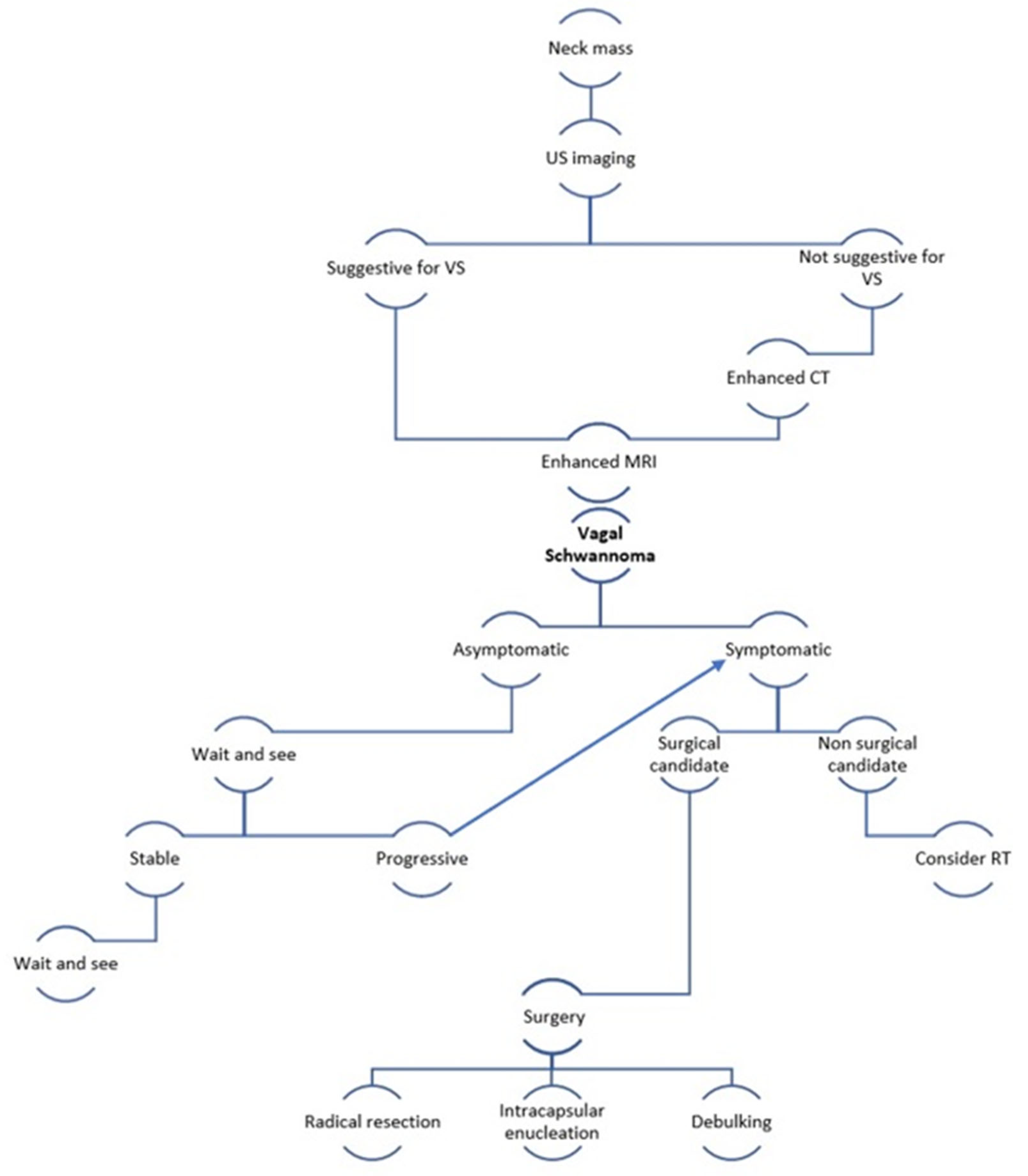

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.L.; Yu, S.Y.; Li, G.K.; Wei, W.I. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: A study of the nerve of origin. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 268, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.E.; Khan, A.; Asiri, M. Supraclavicular Cervical Schwannoma: A Case Report. Cureus 2019, 11, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, J.M.; Selig, A.M.; Crowley, K.; Allen, P.W. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distintive peripheral nerve tumor. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1994, 18, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkkonen, S.T.; Hildén, O.; Hagström, J.; Leivo, I.; Bäck, L.J.; Mäkitie, A.A. Experience of head and neck extracranial schwannomas in a whole population-based single-center patient series. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 271, 3027–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducatman, B.S.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Piepgras, D.G.; Reiman, H.M.; Ilstrup, D.M. Malignant peripheral nerves heath tumors: A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer 1986, 57, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, T.C.; Rich, J.R.; Ward, P.W. Neurilemmoma of the sphenoid sinus. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1974, 100, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colreavy, M.P.; Lacy, P.D.; Hughes, J.; Bouchier-Hayes, D.; Brennan, P.; O’Dwyer, A.J.; Donnelly, M.J.; Gaffney, R.; Maguire, A.; O’Dwyer, T.P.; et al. Head and neck schwannomas—A 10 year review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2000, 114, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, G.; Tan, T.Y. Imaging characteristics of schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain: A review of 12 cases. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010, 31, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo, M.G.; Longo, F.; Marone, U.; Franco, R.; Petrillo, A.; Pezzullo, L. Cervical vagal schwannoma. A case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2009, 29, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdass, A.A.; Yao, M.; Natarajan, S.; Bakshi, P.K. A Rare Case of Vagus Nerve Schwannoma Presenting as a Neck Mass. Am. J. Case Rep. 2017, 18, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Munjal, M.; Rai, D.; Rao, S. Malignant Transformation of Vagal Nerve Schwannoma into Angiosarcoma: A Rare Event. J. Surg. Tech. Case Rep. 2015, 7, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikrishna, B.H.; Jyothi, A.C.; Kulkarni, N.H.; Mazhar, M.S. Extracranial Head and Neck Schwannomas: Our Experience. Ind. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 68, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiun, K.C.; Tang, I.P.; Prepageran, N.; Jayalakshmi, P. An extensive cervical vagal nerve schwannoma: A case report. Med. J. Malays. 2012, 67, 342–344. [Google Scholar]

- Aregawi, A.B. A Rare Case of Cervical Vagal Nerve Schwannoma in a 30-Year-Old Ethiopian Man. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2023, 16, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behuria, S.; Rout, T.K.; Pattanayak, S. Diagnosis and management of schwannomas originating from the cervical vagus nerve. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2015, 97, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Marnane, C.N.; Mal, R.; Baldwin, D. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas—A 10-year review. Auris Nasus Larynx 2007, 34, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, C.E.; Ramos, D.M.; Moyses, R.A.; Durazzo, M.D.; Cernea, C.R.; Ferraz, A.R. Neck nerve trunks schwannomas: Clinical features and postoperative neurologic outcome. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 1579–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, C.; Wang, S.; Liude, H.; Ye, Y.; Chen, X. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: A clinical analysis of 33 patients. Laryngoscope 2007, 117, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosemane, D.; Kabekkodu, S.; Jaipuria, B.; Sreedharan, S.; Shenoy, V. Extracranial non-vestibular head and neck schwannomas: A case series with the review of literature. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, E.; Del Negro, A.; Akashi, H.K.; Araújo, P.P.; Tincani, A.J.; Martins, A.S. Schwannomas in the head and neck: Retrospective analysis of 21 patients and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2007, 125, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, B.K.; Kaushal, M.; Garge, S.; Aggarwal, G. Extra vestibular schwannoma: A two year experience. Ind. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 63, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, C.T.; Nisenbaum, E.; Chyou, D.; Misztal, C.; Yan, D.; Mittal, R.; Young, J.; Tekin, M.; Telischi, F.; Fernandez-Valle, C.; et al. Genomics, Epigenetics, and Hearing Loss in Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Zhao, L. A rare case of bilateral cervical vagal neurofibromas: Role of high-resolution ultrasound. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, K.R.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, H.S. Schwannoma in head and neck: Preoperative imaging study and intracapsular enucleation for functional nerve preservation. Yonsei Med. J. 2010, 51, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, G.; Pattaro, G.; Iorio, O.; Avallone, M.; Silecchia, G. A literature review on surgery for cervical vagal schwannomas. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, R.E.; O’Doherty, M.J. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2002, 15, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kami, Y.N.; Chikui, T.; Okamura, K.; Kubota, Y.; Oobu, K.; Yabuuchi, H.; Nakayama, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Yoshiura, K. Imaging findings of neurogenic tumours in the head and neck region. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2012, 41, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, Y.S.; Chang, K.C. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: A review of 8 years experience. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002, 122, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumatsu, R.; Nakashima, T.; Miyazaki, R.; Segawa, Y.; Komune, S. Diagnosis and management of extracranial head and neck schwannomas: A review of 27 cases. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 2013, 973045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatori, A.; Dionigi, G.; De Monte, L.; Conti, V.; Rotolo, N. Cervico-mediastinal schwannoma of the vagus nerve: Resection with intraoperative nerve monitoring. Updates Surg. 2011, 63, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Lazim, N. Challenges in managing a vagal schwannomas: Lesson learnt. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 53, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, H.; Kaneko, A.; Ota, Y.; Tsukinoki, K. Schwannoma of the mental nerve: Usefulness of preoperative imaging: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2004, 97, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaman, F.D.; Kransdorf, M.J.; Menke, D.M. Schwannoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2004, 24, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, J.; Hodge, J.R.; Frick, M.; Leung, F.P.; Hsu, E.; Gi, M.T.; Venkatesh, S.K. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Appearance of Schwannomas from Head to Toe: A Pictorial Review. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2017, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhar, M.; Harouachi, A.; Bouhout, T.; Serji, B.; El Harroudi, T. A rare association of Vagus Nerve Schwannoma and Pheochromocytoma: A case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 76, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airlangga, P.A.; Prijambodo, B.; Hidayat, A.R.; Benedicta, S. Schwannoma of the upper cervical spine—A case report. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2019, 22, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. Learning from eponyms: Jose Verocay and Verocay bodies, Antoni A and B areas, Nils Antoni and Schwannomas. Ind. Dermatol. Online J. 2012, 3, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, G.; Tan, T.Y. CT and MRI evaluation of nerve sheath tumors of the cervical vagus nerve. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratjevaite, L.; Dreyer, N.S.; Dauksa, A.; Sarauskas, V. Challenging diagnosis of cervical vagal nerve schwannoma. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjac084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saydam, L.; Kizilay, A.; Kalcioglu, T.; Gurer, I. Ancient cervical vagal neurilemmoma: A case report. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2000, 21, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, P.M.; Curtin, H.D. Parapharyngeal Space. In Head and Neck Imaging, 3rd ed.; Som, P.M., Curtin, H.D., Eds.; Mosby: Saint Louis, MO, USA, 1996; Volume 2, pp. 915–951. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, M.; Furukawa, M.K.; Katoh, K.; Tsukuda, M. Differentiation between schwannoma of the vagus nerve and schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain by imaging diagnosis. Laryngoscope 1996, 106, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibber, M.J.; Zevallos, J.P.; Urken, M.L. Enucleation of vagal nerve schwannoma using intraoperative nerve monitoring. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 790–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akheel, M.; Mohd Athar, I.; Ashmi, W. Schwannomas of the head and neck region: A report of two cases with a narrative review of the literature. Cancer Res. Stat. Treat. 2020, 3, 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, P. Extracranial non-vestibular head and neck schwannomas. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentino, J.; Boggess, M.A.; Ellis, J.L.; Hester, T.O.; Jones, R.O. Expected neurologic outcomes for surgical treatment of cervical neurilemmomas. Laryngoscope 1998, 108, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Martel, W. Cross-sectional imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Characteristic signs on CT, MR imaging, and sonography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001, 176, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, L. Pre-operative embolization and excision of vagal schwannoma with rich vascular supply: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2022, 101, 28760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijichi, K.; Kawakita, D.; Maseki, S.; Beppu, S.; Takano, G.; Murakami, S. Functional Nerve Preservation in Extracranial Head and Neck Schwannoma Surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer-Hill, H.S.; Kline, D.G. Neurogenic tumors of the cervical vagus nerve: Report of four cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 2000, 46, 1498–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafif, A.; Segev, Y.; Kaplan, D.M.; Gil, Z.; Fliss, D.M. Surgical management of parapharyngeal space tumors: A 10-year review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005, 132, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.; Alam, M.S. “Collateral Damage”: Horner’s Syndrome Following Excision of a Cervical Vagal schwannoma. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2018, 8, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aguado, R.; Morales-Angulo, C.; Obeso-Agüera, S.; Longarela-Herrero, Y.; García-Zornoza, R.; Acle Cervera, L. Horner’s syndrome after neck surgery. Acta Otorrinolaringol. 2012, 63, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.; Pongpaopattanakul, P.; Chauhan, R.A.; Brack, K.E.; Ng, G.A. The Effects of Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Ventricular Electrophysiology and Nitric Oxide Release in the Rabbit Heart. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 867705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafit, D.; Horowitz, G.; Vital, I.; Locketz, G.; Fliss, D.M. An algorithm for treating extracranial head and neck schwannomas. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 2035–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fionda, B.; Rembielak, A. Is There Still a Role for Radiation Therapy in the Management of Benign Conditions? Clin. Oncol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.Y.; Kondziolka, D.; Niranjan, A.; Flickinger, J.C.; Lunsford, L.D. Gamma Knife surgery for schwannomas originating from cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 109, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lou, J.; Qiu, S.; Guo, Y.; Pan, M. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for dumbbell-shaped hypoglossal schwannomas: Two cases of long-term follow-up and a review of the literature. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichkorn, T.; Regnery, S.; Held, T.; Kronsteiner, D.; Hörner-Rieber, J.; El Shafie, R.A.; Herfarth, K.; Debus, J.; König, L. Effectiveness and Toxicity of Fractionated Proton Beam Radiotherapy for Cranial Nerve Schwannoma Unsuitable for Stereotactic Radiosurgery. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 772831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Park, C.K.; Jung, N.Y.; Jung, H.H.; Chang, J.H.; Chang, J.W.; Chang, W.S. Early-onset adverse events after stereotactic radiosurgery for jugular foramen schwannoma: A mid-term follow-up single-center review of 46 cases. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzouqi, B.; El Bouhmadi, K.; Oukesou, Y.; Rouadi, S.; Abada, R.L.; Roubal, M.; Mahtar, M. Head and neck paragangliomas: Ten years of experience in a third health center. A cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 66, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshelava, G.; Robakidze, Z. Cervical Vagal Schwannoma Causing Asymptomatic Internal Carotid Artery Compression. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 63, 460.e9–460.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Result |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 10 |

| M/F | 5/5 |

| Mean Age | 52.7 ys (23–67) |

| Average tumor size | 3.6 cm (1–5) |

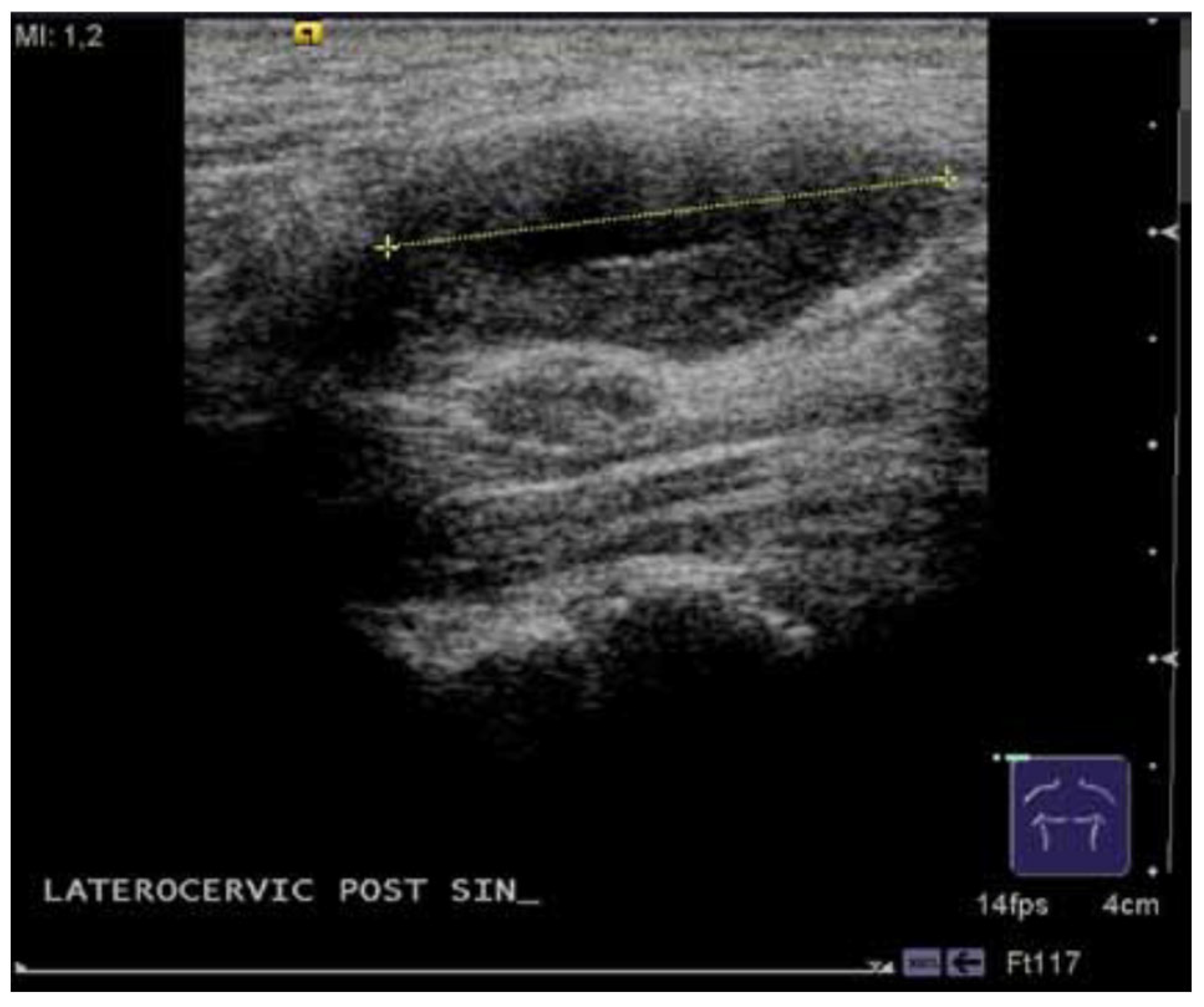

| US | 9 |

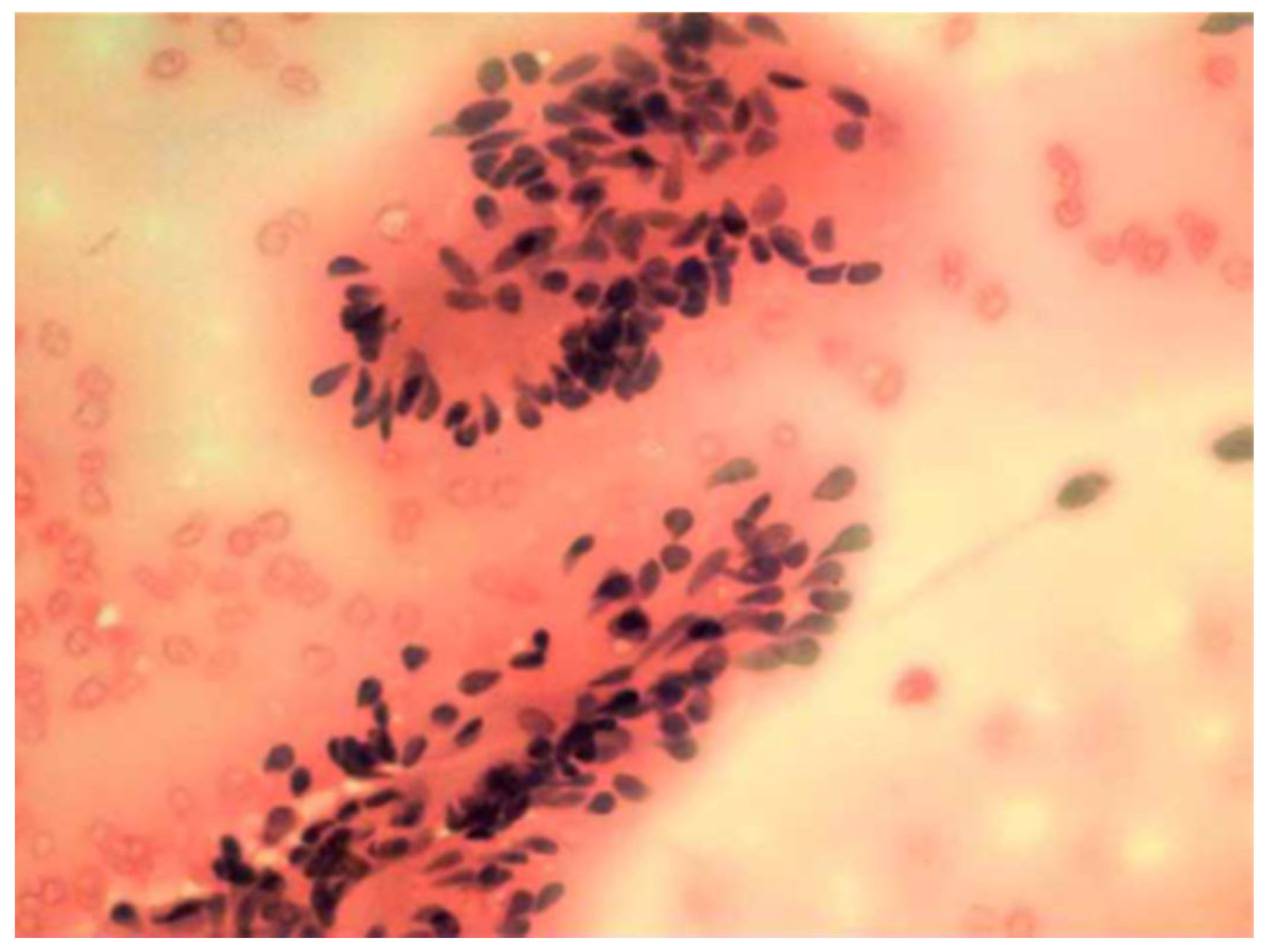

| FNAC | 6 |

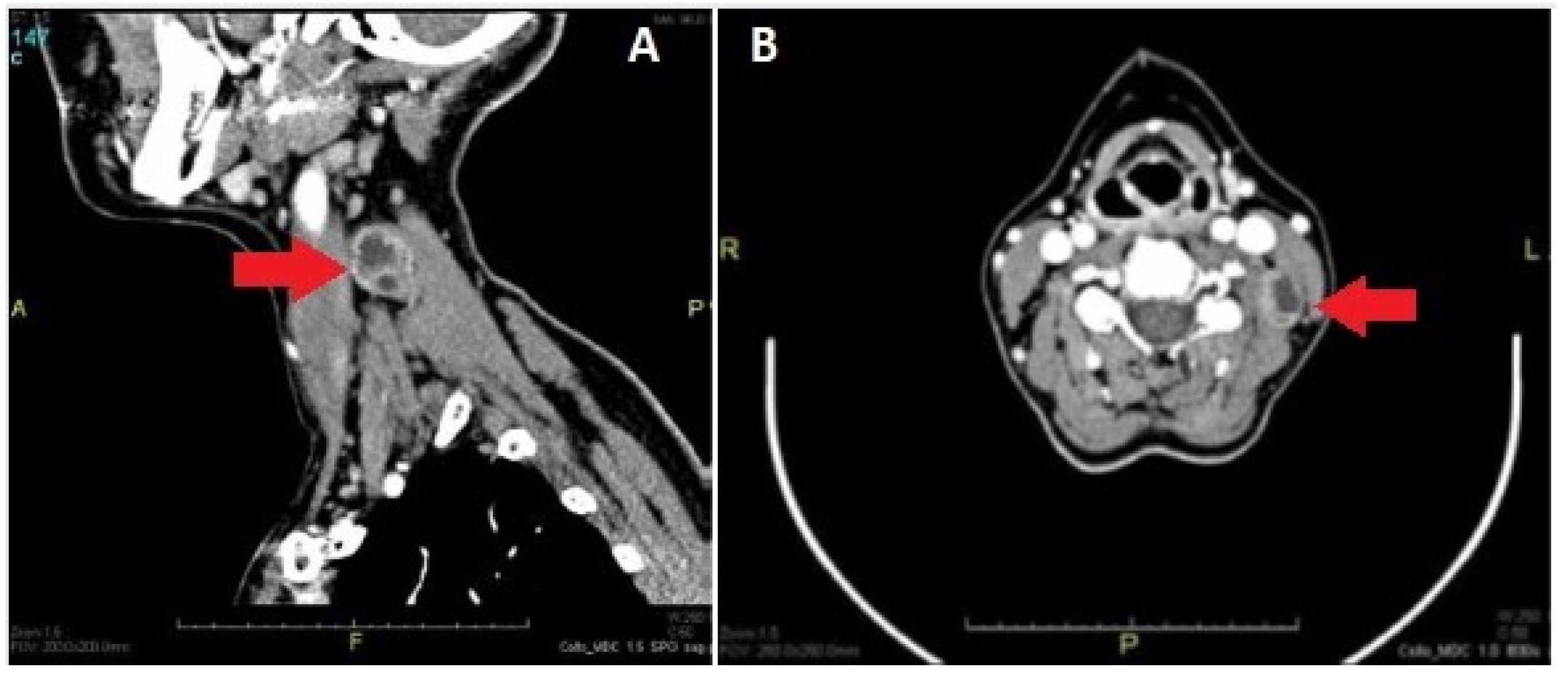

| CT | 6 |

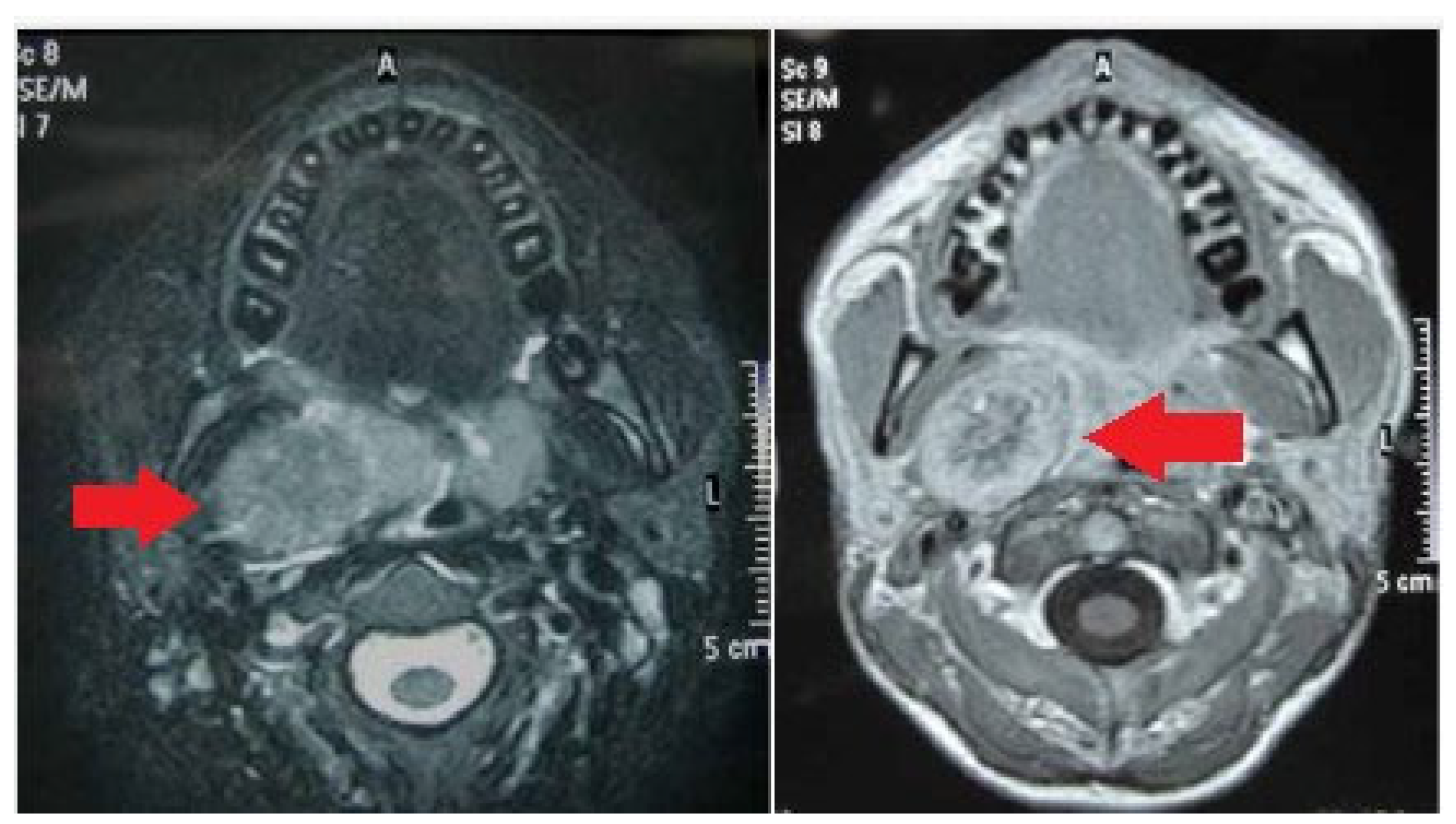

| MRI | 7 |

| Treatment approach | Surgery |

| Post-surgical sequelae | Hoarseness: 6 |

| Recurrent nerve palsy: 4 | |

| Horner’s syndrome: 2 | |

| Alteration of heart rate: 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loperfido, A.; Celebrini, A.; Fionda, B.; Bellocchi, G.; Cristalli, G. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Vagal Schwannoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59061013

Loperfido A, Celebrini A, Fionda B, Bellocchi G, Cristalli G. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Vagal Schwannoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Medicina. 2023; 59(6):1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59061013

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoperfido, Antonella, Alessandra Celebrini, Bruno Fionda, Gianluca Bellocchi, and Giovanni Cristalli. 2023. "Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Vagal Schwannoma: Case Series and Literature Review" Medicina 59, no. 6: 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59061013

APA StyleLoperfido, A., Celebrini, A., Fionda, B., Bellocchi, G., & Cristalli, G. (2023). Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Vagal Schwannoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Medicina, 59(6), 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59061013