Personalizing Clozapine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of MicroRNA Biomarkers—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

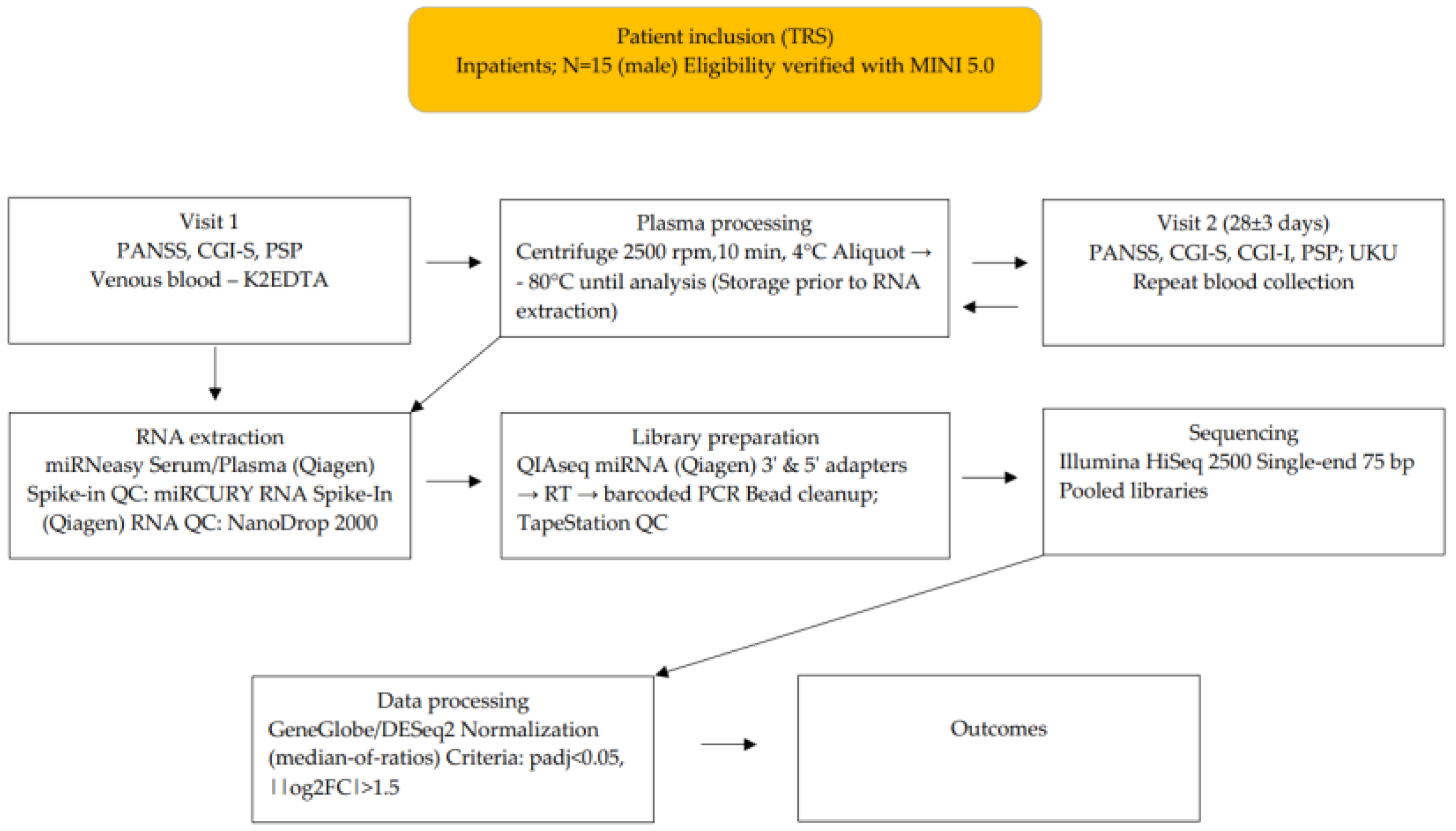

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy of Clozapine Therapy

3.2. Safety of Clozapine Therapy

3.3. Characteristics of MiRNAs

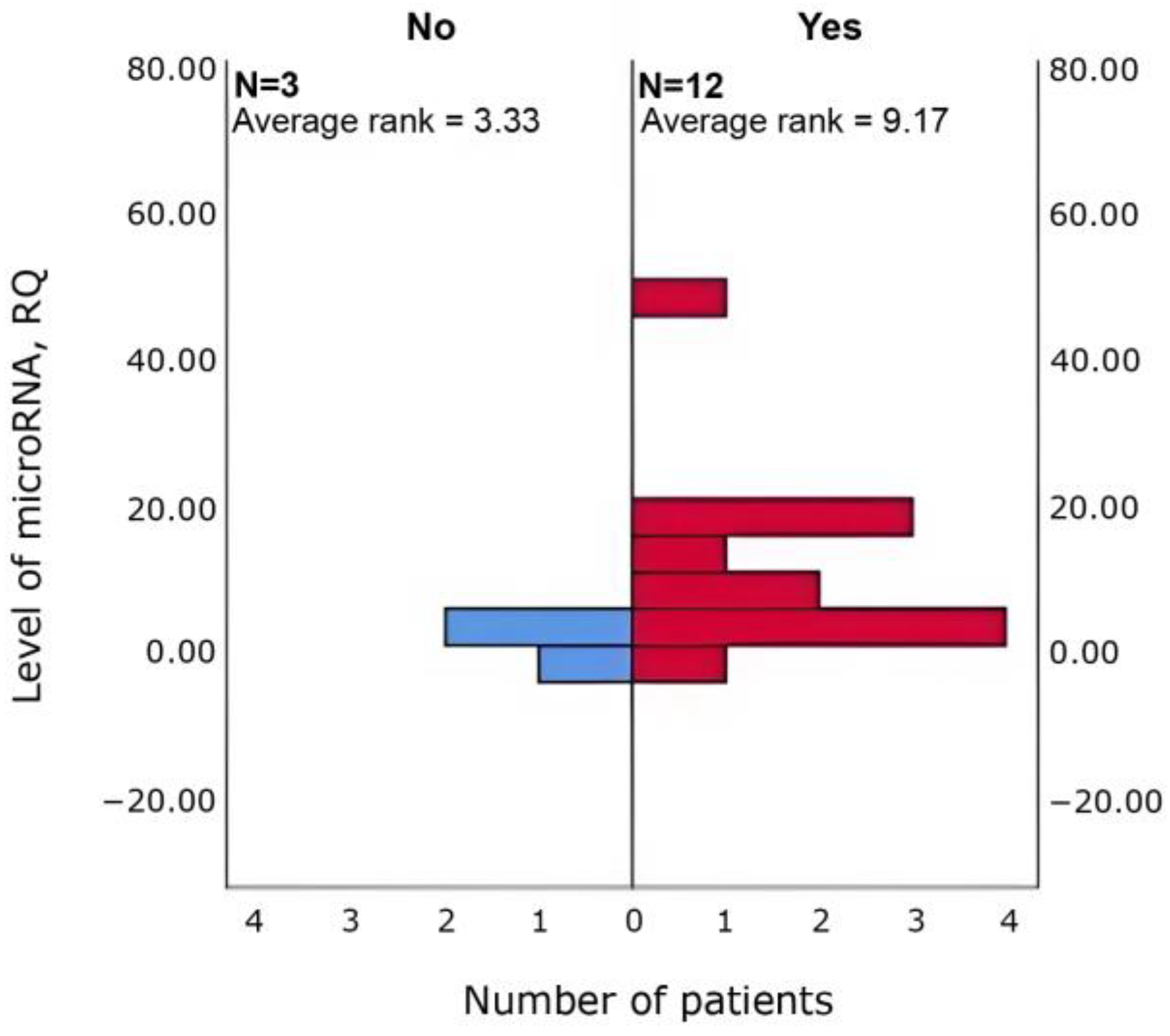

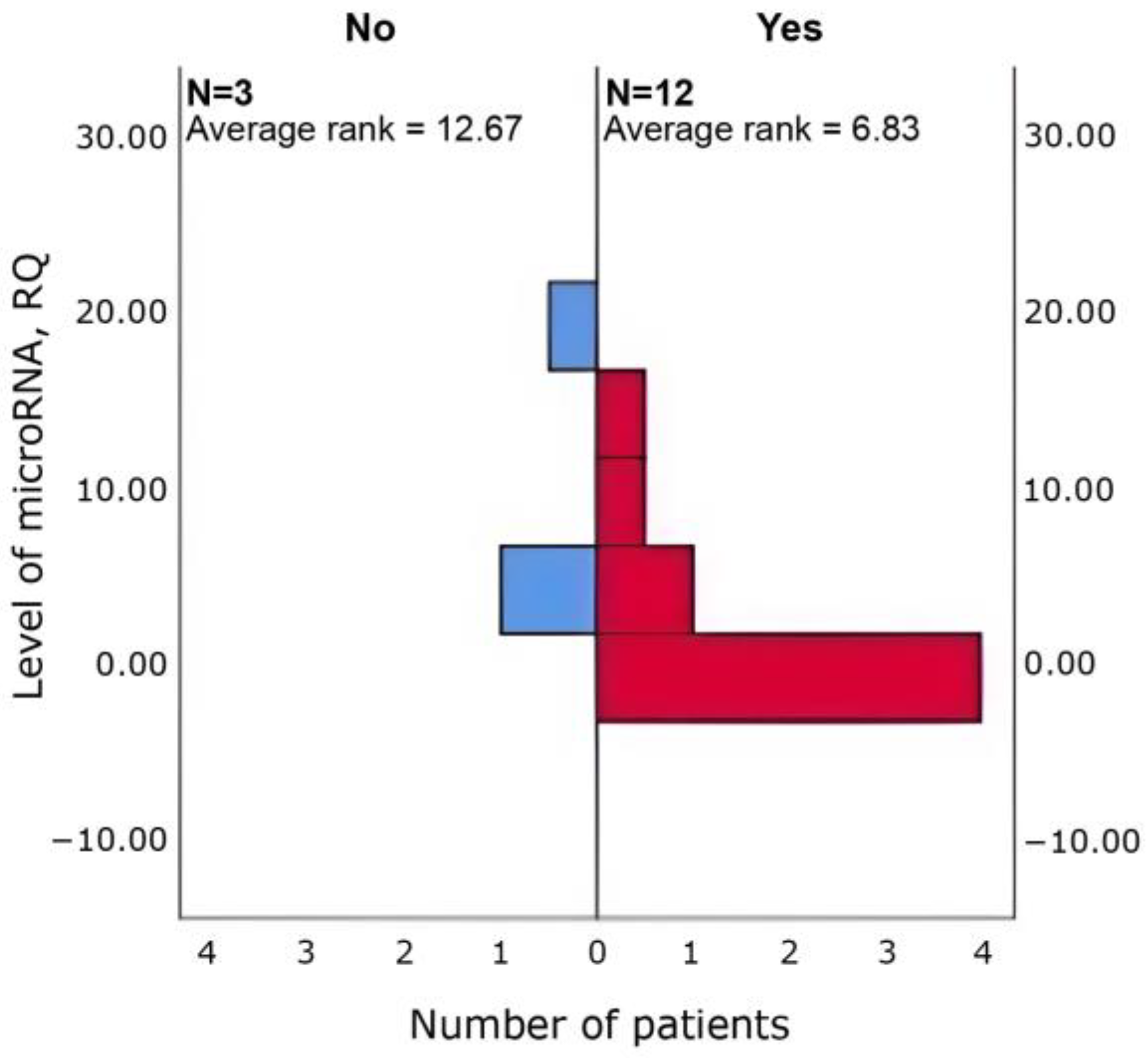

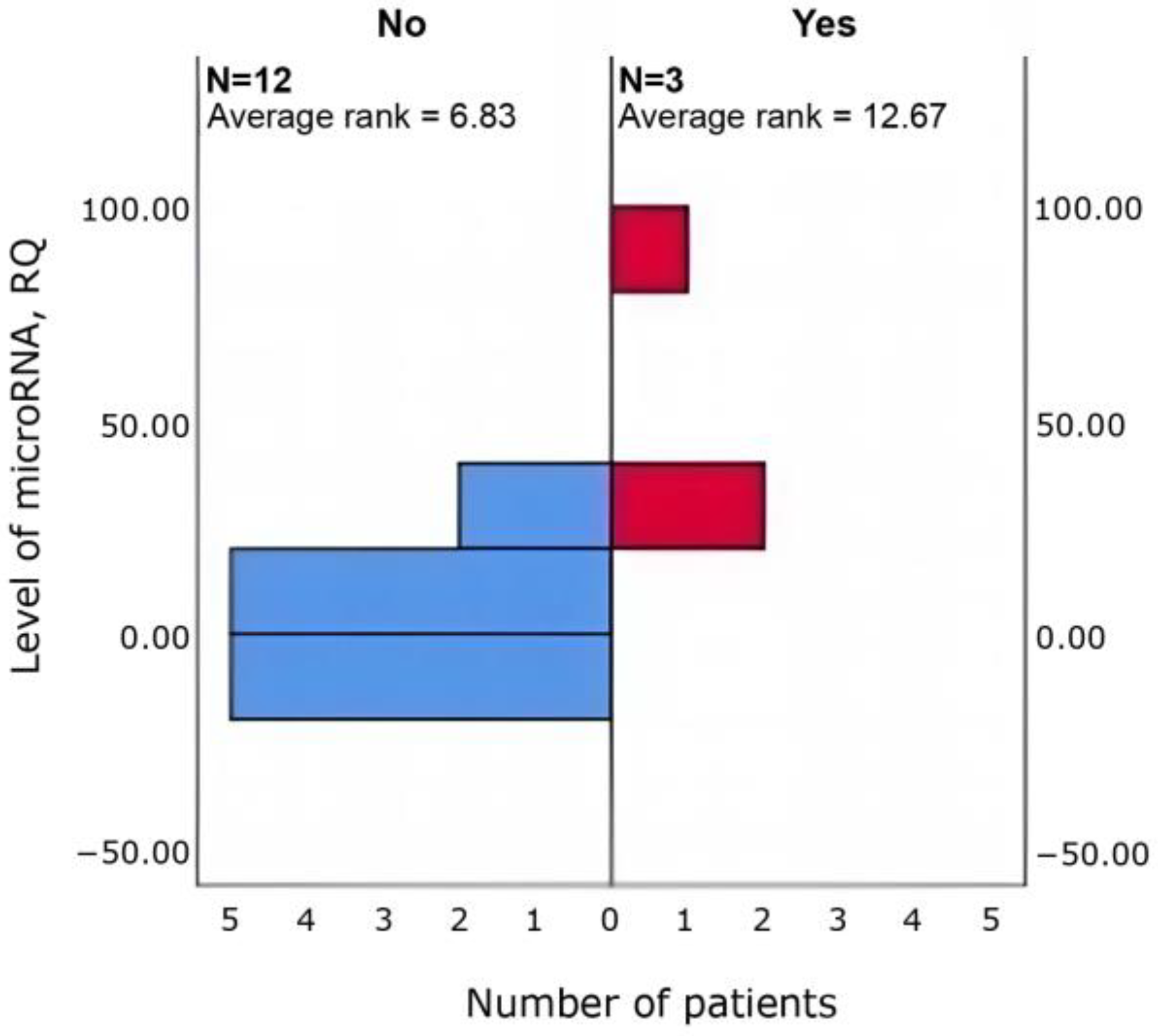

3.4. Relationships Between Clinical Parameters and miRNA Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADR | Adverse Drug Reaction |

| CGI-I | Clinical Global Impression—Improvement |

| CGI-S | Clinical Global Impression—Severity |

| DIANA-miRPath v4.0 | Deoxyribonucleic Acid Intelligent Analysis—microRNA Pathway Analysis, version 4.0м |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| GRINA | Glutamate Ionotropic Receptor NMDA Type Subunit Associated Protein 1 |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| KEGG | Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

| K2EDTA Intravacuate tubes | Vacutainer tubes containing dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid as an anticoagulant |

| MINI 5.0 | Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, version 5.0 |

| miRNA | Micro Ribonucleic Acid |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PSP | Personal and Social Performance Scale |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| TRS | Treatment resistant schizophrenia |

| UKU | Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser Side Effect Rating Scale |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

References

- Jauhar, S.; Johnstone, M.; McKenna, P.J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2022, 399, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juckel, G.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Gorwood, P.; Mosolov, S.; Pani, L.; Rossi, A.; Sanjuan, J. Towards a framework for treatment effectiveness in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1867–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, J.; Chew, Q.H.; McIntyre, R.S.; Sim, K. Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia, Clozapine Resistance, Genetic Associations, and Implications for Precision Psychiatry: A Scoping Review. Genes 2023, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkis, H.; Buckley, P.F. Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 2016, 39, 239–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Falkai, P.; Wobrock, T.; Lieberman, J.; Glenthøj, B.; Gattaz, W.F.; Thibaut, F.; Möller, H.J. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia—A short version for primary care. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2017, 21, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.L.; Altar, C.A.; Taylor, D.L.; Degtiar, I.; Hornberger, J.C. The social and economic burden of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 29, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, B.; Yada, Y.; So, R.; Takaki, M.; Yamada, N. The critical treatment window of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Secondary analysis of an observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 250, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Cao, T.; Cai, H. Peripheral biomarkers of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Genetic, inflammation and stress perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1005702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, D.; Penedo, M.A.; Rivera-Baltanás, T.; Peña-Centeno, T.; Burkhardt, S.; Fischer, A.; Prieto-González, J.M.; Olivares, J.M.; López-Fernández, H.; Agís-Balboa, R.C. MiRNA Differences Related to Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Morales, R.; Agís-Balboa, R.C.; Esteller, M.; Berdasco, M. Epigenetic mechanisms during ageing and neurogenesis as novel therapeutic avenues in human brain disorders. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.C.; Du, Y.; Chen, L.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Cheng, Y. MicroRNA schizophrenia: Etiology, biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 146, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwalkar, P.; Khire, A.; Shirsat, N. Validation of microRNA Target Genes Using Luciferase Reporter assay and Western Blot Analysis. In Medulloblastoma: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, S.; Yamamura, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Motomura, E.; Okada, M. Clozapine, but not haloperidol, enhances glial d-serine and L-glutamate release in rat frontal cortex and primary cultured astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, S.; Schulte, P.; Begemann, M.; Engelsbel, F.; de Haan, L. Clozapine Augmented with Glutamate Modulators in Refractory Schizophrenia: A Review and Metaanalysis. Pharmacopsychiatry 2014, 47, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.Y.; Zhong, P.; Yan, Z. Homeostatic regulation of glutamatergic transmission by dopamine D4 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22308–22313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59 (Suppl. 2), 22–33; quiz 34–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aboraya, A.; Nasrallah, H.A. Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): Use, misuse, drawbacks, and a new alternative for schizophrenia research. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.R.; Shankles, E.B.; Polissar, N.L. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 17, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morosini, P.L.; Magliano, L.; Brambilla, L.; Ugolini, S.; Pioli, R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schouby Bock, M.; Nørgaard Van Achter, O.; Dines, D.; Simonsen Speed, M.; Correll, C.U.; Mors, O.; Østergaard, S.D.; Kølbæk, P. Clinical validation of the self-reported Glasgow Antipsychotic Side-effect Scale using the clinician-rated UKU side-effect scale as gold standard reference. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastsoglou, S.; Skoufos, G.; Miliotis, M.; Karagkouni, D.; Koutsoukos, I.; Karavangeli, A.; Kardaras, F.S.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. DIANA-miRPath v4.0: Expanding target-based miRNA functional analysis in cell-type and tissue contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W154–W159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smessaert, S.; Detraux, J.; Desplenter, F.; De Hert, M. Evaluating Monitoring Guidelines of Clozapine-Induced Adverse Effects: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Guo, C.; He, L.; Shi, Y. MiRNAs of peripheral blood as the biomarker of schizophrenia. Hereditas 2018, 155, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Bao, C.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, J.; Hu, G.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Yi, Z. MicroRNA-195 predicts olanzapine response in drug-free patients with schizophrenia: A prospective cohort study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 35, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alacam, H.; Akgun, S.; Akca, H.; Ozturk, O.; Kabukcu, B.B.; Herken, H. miR-181b-5p, miR-195-5p and miR-301a-3p are related with treatment resistance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Zhang, Y.; Long, Q.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Lu, Z.; Yang, W.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Teng, Z.; et al. Investigating aberrantly expressed microRNAs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia using miRNA sequencing and integrated bioinformatics. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 4340–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotas, M.; Stańczykiewicz, B.; Sporniak, B.; Pawlak, E.; Misiak, B. A systematic review of miRNA expression in schizophrenia spectrum disorders across the blood and the brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 176, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funahashi, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Iga, J.-I.; Ueno, S.-I. Impact of clozapine on the expression of miR-675-3p in plasma exosomes derived from patients with schizophrenia. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, S.A.; Dal, I.; Özkan-Kotiloğlu, S.; Baskak, B.; Kaya-Akyüzlü, D. Pharmacoepigenetics in schizophrenia: Predicting drug response. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 107597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Cong, Q.; Chen, D.; Yi, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Zeng, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. miR143-3p–Mediated NRG-1–Dependent Mitochondrial Dysfunction Contributes to Olanzapine Resistance in Refractory Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 92, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, C.; Dang, X.; Luo, X.J. Mendelian randomization reveals the causal links between microRNA and schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 163, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Campdelacreu, J.; Vilas, D.; Ispierto, L.; Reñé, R.; Álvarez, R.; Armengol, M.P.; Borràs, F.E.; Beyer, K. Exploratory study on microRNA profiles from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpan, D.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S. Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and miRNA expression in frontal and temporal neocortex in Alzheimer’s disease and the effect of TNF-α on miRNA expression in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2011, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geekiyanage, H.; Jicha, G.A.; Nelson, P.T.; Chan, C. Blood serum miRNA: Non-invasive biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 235, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geekiyanage, H.; Chan, C. MicroRNA-137/181c Regulates Serine Palmitoyltransferase and In Turn Amyloid β, Novel Targets in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 14820–14830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Chen, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, D.; Jiao, J.; Sun, W.; Xiang, Y. Heteromultivalent scaffolds fabricated by biomimetic co-assembly of DNA–RNA building blocks for the multi-analysis of miRNAs. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Ravan, H.; Mehrabani, M. Multiplex monitoring of Alzheimer associated miRNAs based on the modular logic circuit operation and doping of catalytic hairpin assembly. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 170, 112710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.; Piscopo, P.; Talarico, G.; Ricci, L.; Crestini, A.; Tosto, G.; Gasparini, M.; Bruno, G.; Denti, M.A.; Confaloni, A. Plasma microRNA profiling distinguishes patients with frontotemporal dementia from healthy subjects. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 84, e1–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Orlov, E.; Gowda, P.; Bose, C.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Lahiri, D.K.; Reddy, P.H. Synaptosome microRNAs regulate synapse functions in Alzheimer’s disease. NPJ Genom. Med. 2022, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zou, L.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wu, H.; et al. Prognostic plasma exosomal microRNA biomarkers in patients with substance use disorders presenting comorbid with anxiety and depression. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lin, M.; Chen, J.; Pedrosa, E.; Hrabovsky, A.; Fourcade, H.M.; Zheng, D.; Lachman, H.M. MicroRNA Profiling of Neurons Generated Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived from Patients with Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder, and 22q11.2 Del. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zang, Z.; Braun, U.; Schwarz, K.; Harneit, A.; Kremer, T.; Ma, R.; Schweiger, J.; Moessnang, C.; Geiger, L.; et al. Association of a Reproducible Epigenetic Risk Profile for Schizophrenia With Brain Methylation and Function. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Chen, C.Y.; Li, Z.; Martin, A.R.; Bryois, J.; Ma, X.; Gaspar, H.; Ikeda, M.; Benyamin, B.; Brown, B.C.; et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.K.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yu, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, W.Q.; Yang, Y.F.; Xiao, X.; Yan, H.; Lu, T.L.; et al. Prediction of treatment response to antipsychotic drugs for precision medicine approach to schizophrenia: Randomized trials and multiomics analysis. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, P.; Wu, T.; Zhu, S.; Deng, L.; Cui, G. Axon guidance pathway genes are associated with schizophrenia risk. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, A. The neuregulin signaling pathway and schizophrenia: From genes to synapses and neural circuits. Brain Res. Bull. 2010, 83, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stornetta, R.L.; Zhu, J.J. Ras and Rap Signaling in Synaptic Plasticity and Mental Disorders. Neurosci. 2011, 17, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Yin, X.; Zhu, Z.; Hou, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Yu, Q.; Hui, L. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis and lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA establishment of schizophrenia based on induced pluripotent stem cells. Schizophr. Res. 2025, 281, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manafzadeh, F.; Baradaran, B.; Noor Azar, S.G.; Javidi Aghdam, K.; Dabbaghipour, R.; Shayannia, A.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Expression study of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway associated lncRNAs in schizophrenia. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2025, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranz, T.M.; Goetz, R.R.; Walsh-Messinger, J.; Goetz, D.; Antonius, D.; Dolgalev, I.; Heguy, A.; Seandel, M.; Malaspina, D.; Chao, M.V. Rare variants in the neurotrophin signaling pathway implicated in schizophrenia risk. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 168, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Cui, F.; Yin, J.; Fang, C.; Liu, L. Altered mRNA expression levels of autophagy- and apoptosis-related genes in the FOXO pathway in schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 746, 135669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J. Dysregulation of neural calcium signaling in Alzheimer disease, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Prion 2013, 7, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedracka-Krok, S.; Swiderska, B.; Jankowska, U.; Skupien-Rabian, B.; Solich, J.; Buczak, K.; Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, M. Clozapine influences cytoskeleton structure and calcium homeostasis in rat cerebral cortex and has a different proteomic profile than risperidone. J. Neurochem. 2015, 132, 657–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khokhar, J.Y.; Henricks, A.M.; Sullivan, E.D.K.; Green, A.I. Unique Effects of Clozapine: A Pharmacological Perspective. Adv. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, E.; Brzezińska-Błaszczyk, E.; Wysokiński, A.; Żelechowska, P. Systemic concentration of apelin, but not resistin or chemerin, is altered in patients with schizophrenia. J. Investig. Med. 2021, 69, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catak, Z.; Kaya, H.; Kocdemir, E.; Ugur, K.; Pilten, G.S.; Yardim, M.; Sahin, I.; Piril, A.E.; Aydin, S. Interaction of apelin, elabela and nitric oxide in schizophrenia patients. J. Med. Biochem. 2019, 39, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahpolat, M.; Ari, M.; Kokacya, M.H. Plasma Apelin, Visfatin and Resistin Levels in Patients with First Episode Psychosis and Chronic Schizophrenia. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujović, N.; Piron, M.J.; Qian, J.; Chellappa, S.L.; Nedeltcheva, A.; Barr, D.; Heng, S.W.; Kerlin, K.; Srivastav, S.; Wang, W.; et al. Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1486–1498.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| miRNA | log2FoldChange | padj |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-451a | −23.65 | 0.0001 |

| hsa-miR-129-5p | −3.31 | 0.046 |

| hsa-miR-203b-5p | 1.29 | 0.047 |

| hsa-miR-6873-3p | 1.47 | 0.008 |

| hsa-miR-9902-1 | 2.06 | 0.001 |

| hsa-miR-9902-2 | 2.06 | 0.001 |

| hsa-miR-615-3p | 2.39 | 0.015 |

| hsa-miR-4510 | 2.78 | 0.077 |

| hsa-miR-7847-3p | 2.82 | 0.008 |

| hsa-miR-4472 | 2.92 | 0.003 |

| hsa-miR-4449 | 3.23 | 0.001 |

| hsa-miR-6509-5p | 3.47 | 0.031 |

| hsa-miR-6512-5p | 3.58 | 0.033 |

| hsa-miR-6814-5p | 3.60 | 0.046 |

| hsa-miR-6068 | 3.62 | 0.047 |

| hsa-miR-7853-3p | 3.85 | 0.026 |

| hsa-miR-4715-3p | 3.93 | 0.008 |

| hsa-miR-329-1-5p | 4.26 | 0.046 |

| hsa-miR-6078 | 4.43 | 0.007 |

| hsa-miR-3121-3p | 4.85 | 0.009 |

| hsa-miR-548i | 4.90 | 0.020 |

| hsa-miR-4255 | 5.77 | 0.001 |

| Clozapine Safety | Clozapine Efficacy |

|---|---|

| Asthenia hsa-miR-4472 | General efficacy hsa-miR-6814-5p |

| Increased sleep duration hsa-miR-4472 hsa-miR-4510 | Positive symptoms hsa-miR-129-5p hsa-miR-6068 hsa-miR-6814-5p |

| Tachycardia hsa-miR-615-3p hsa-miR-4715-3p | General psychopathological symptoms hsa-miR-128-1-5p |

| Weight gain hsa-miR-329-1-5p |

| miRNA | Term Name | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Clozapine efficacy | ||

| hsa-miR-129-5p hsa-miR-6068 hsa-miR-6814-5p hsa-miR-128-1-5p | Axon guidance | 2.16 × 10−16 |

| Clozapine safety | ||

| hsa-miR-4472 | Axon guidance | 5.55 × 10−8 |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 0.00000113 | |

| Calcium signaling pathway | 0.00000785 | |

| Ras signaling pathway | 0.000416 | |

| Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 0.00777 | |

| Wnt Signaling Pathway | 0.00863 | |

| hsa-miR-4510 | Axon guidance | 4.07 × 10−11 |

| Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 4.52 × 10−8 | |

| Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 0.00000108 | |

| Synaptic vesicle cycle | 0.00000214 | |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 0.00000418 | |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 0.0000438 | |

| Calcium signaling pathway | 0.0000424 | |

| Ras signaling pathway | 0.000183 | |

| hsa-miR-615-3p | Analysis yielded no significant results | |

| hsa-miR-4715-3p | Apelin signaling pathway | 0.0000363 |

| Calcium signaling pathway | 0.000618 | |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 0.000819 | |

| FoxO signaling pathway | 0.00120 | |

| hsa-miR-329-1-5p (hsa-miR-329-5p) 1 | ErbB signaling pathway | 1.17 × 10−7 |

| Axon guidance | 5.94 × 10−7 | |

| Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 0.00000770 | |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 0.000275 | |

| Metabolic pathways | 0.000879 | |

| Prolactin signaling pathway | 0.00312 | |

| Cholesterol metabolism | 0.00465 | |

| Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 0.00515 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sosin, D.N.; Khasanova, A.K.; Illarionov, R.A.; Popova, A.K.; Mirzaev, K.B.; Glotov, A.S.; Mosolov, S.N.; Sychev, D.A. Personalizing Clozapine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of MicroRNA Biomarkers—A Pilot Study. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121020

Sosin DN, Khasanova AK, Illarionov RA, Popova AK, Mirzaev KB, Glotov AS, Mosolov SN, Sychev DA. Personalizing Clozapine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of MicroRNA Biomarkers—A Pilot Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSosin, Dmitry N., Aiperi K. Khasanova, Roman A. Illarionov, Anastasia K. Popova, Karin B. Mirzaev, Andrey S. Glotov, Sergey N. Mosolov, and Dmitry A. Sychev. 2025. "Personalizing Clozapine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of MicroRNA Biomarkers—A Pilot Study" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121020

APA StyleSosin, D. N., Khasanova, A. K., Illarionov, R. A., Popova, A. K., Mirzaev, K. B., Glotov, A. S., Mosolov, S. N., & Sychev, D. A. (2025). Personalizing Clozapine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of MicroRNA Biomarkers—A Pilot Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121020