A Spectrochemically Driven Study: Identifying Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Helichrysum stoechas, Lavandula pedunculata, and Thymus mastichina with Potential to Revert Skin Aging Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy

| Region (cm−1) | Assignment | References | Hs | Lp | Tm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a 3382–3278 | ν(O–H) | [34,35] | 3278 | 3382 | 3367 |

| b 2935–2930 | νantisym(CH3 and CH2), aliphatic compounds | [36,37] | 2930 | 2935 | 2935 |

| c 2885–2881 | νsym(CH3 and CH2), aliphatic compounds | [38,39] | 2884 | 2881 | 2885 |

| d 1714–1690 | ν(C=O) in COOH | [36,37,40] | 1690 | 1713 | 1714 |

| e 1661–1660 | ν(C–C) aromatic ring, ν(C=O) in COOH | [34,35,40] | – | 1661 | 1660 |

| f 1606–1599 | ν(C=C) aromatic ring | [34,36,40] | 1599 | 1606 | 1606 |

| g 1517–1515 | ν(C–C) aromatic ring | [34,35,39] | 1516 | 1517 | 1515 |

| h 1497–1446 | δ(CH3 and CH2) aliphatic compounds, polysaccharides; ν(C–C) aromatic ring | [35,36,37] | 1497w; 1446 | 1494sh; 1449 | 1495vw; 1449 |

| i 1286–1264 | δ(C–H), ν(C–OH) | [34,39] | 1283; 1264sh | 1286sh; 1267 | 1285; 1267sh |

| j 1175–1101 | ν(C–O–C) ester, ν(C–O) and δ(C–OH) carbohydrates | [36,37] | 1160; 1101 | 1175; 1117 | 1179; 1102 |

| k 1077–1033 | ν(C–O) and ν(C–C) carbohydrates | [37,38] | 1062; 1033sh | 1077; 1051sh | 1077; 1051sh |

2.2. Total Phenolic and Total Flavonoid Contents and Cell-Free Antioxidant Activity

2.3. HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn Analysis

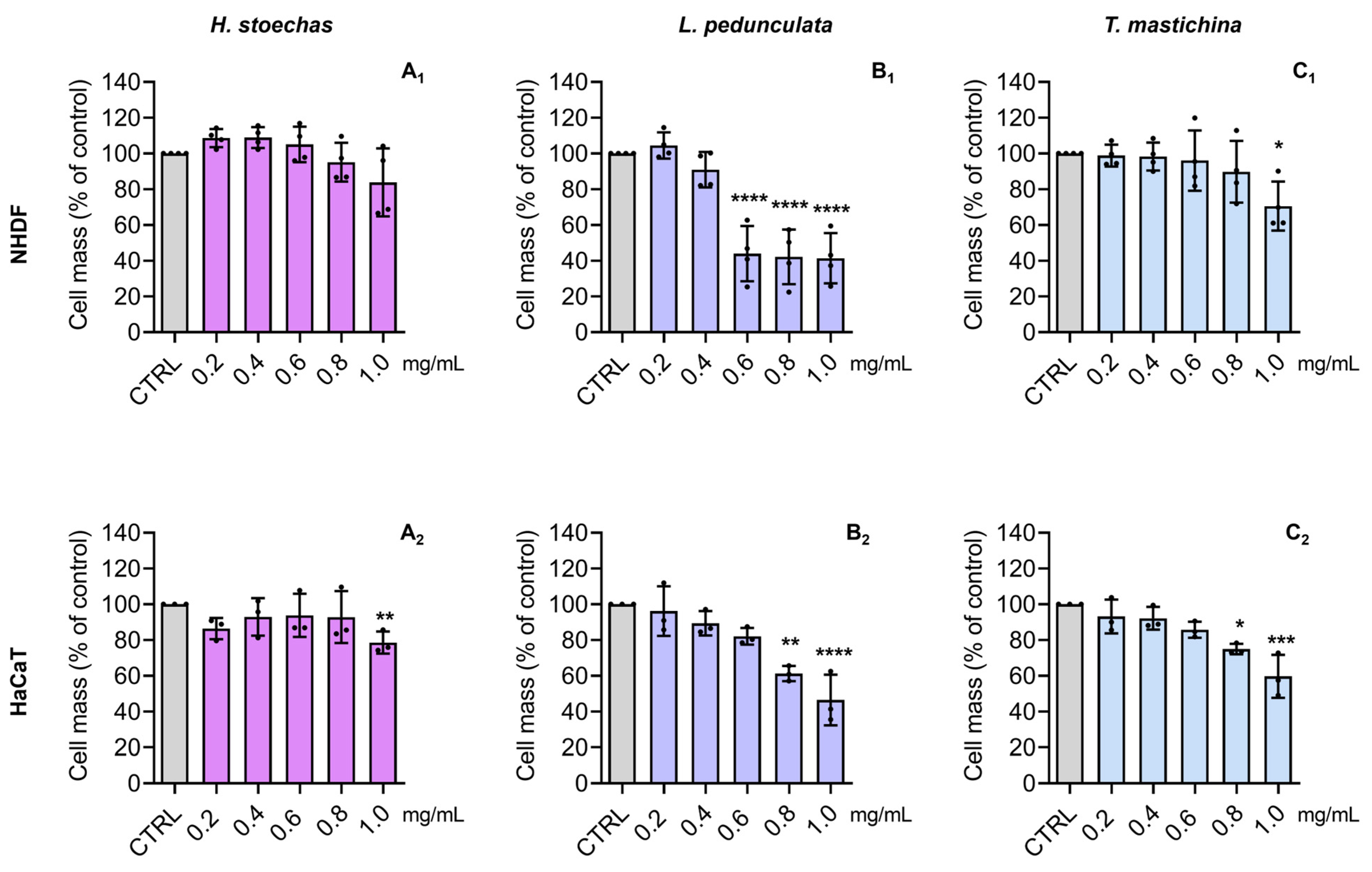

2.4. Cytotoxic Effects on Normal Skin Cells

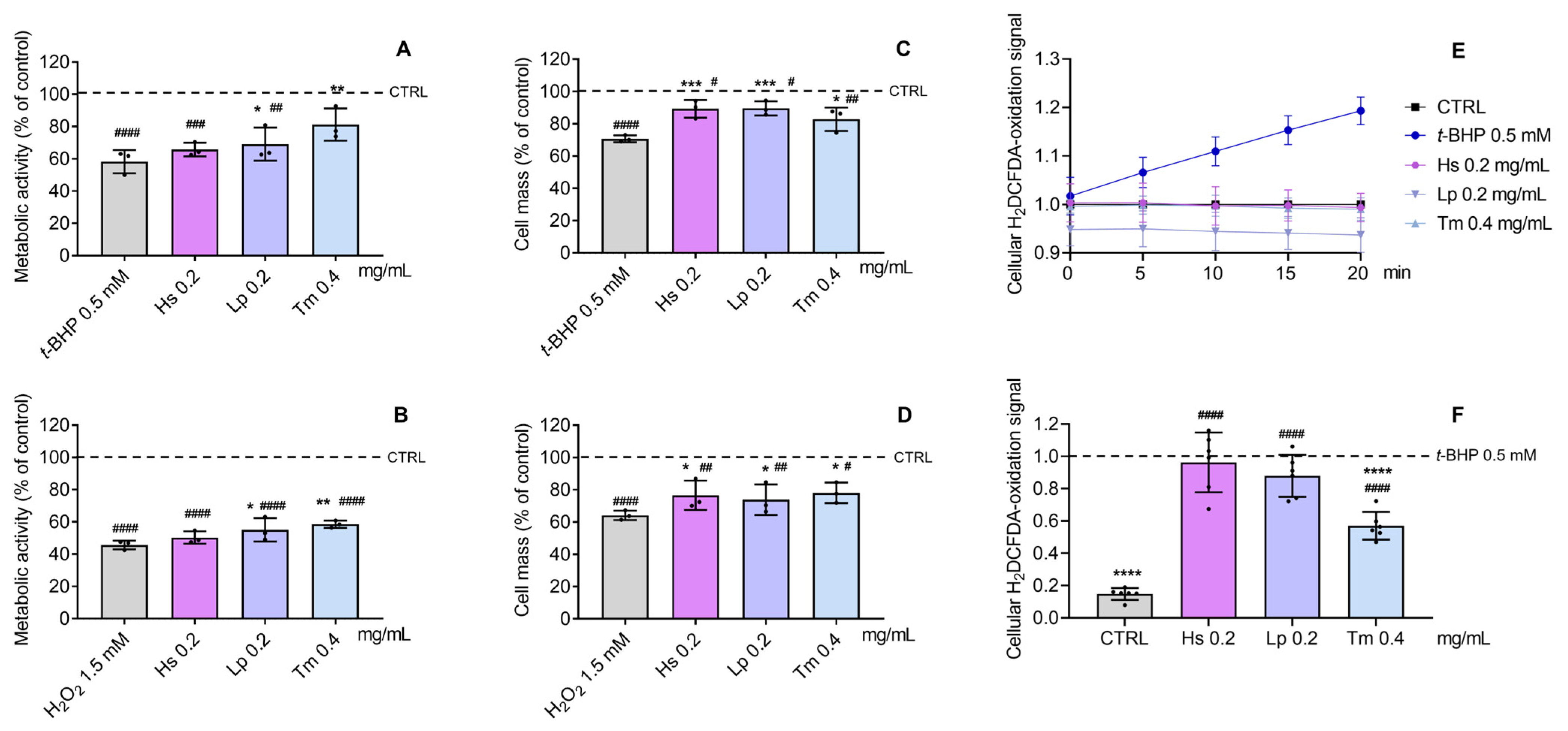

2.5. Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Effects

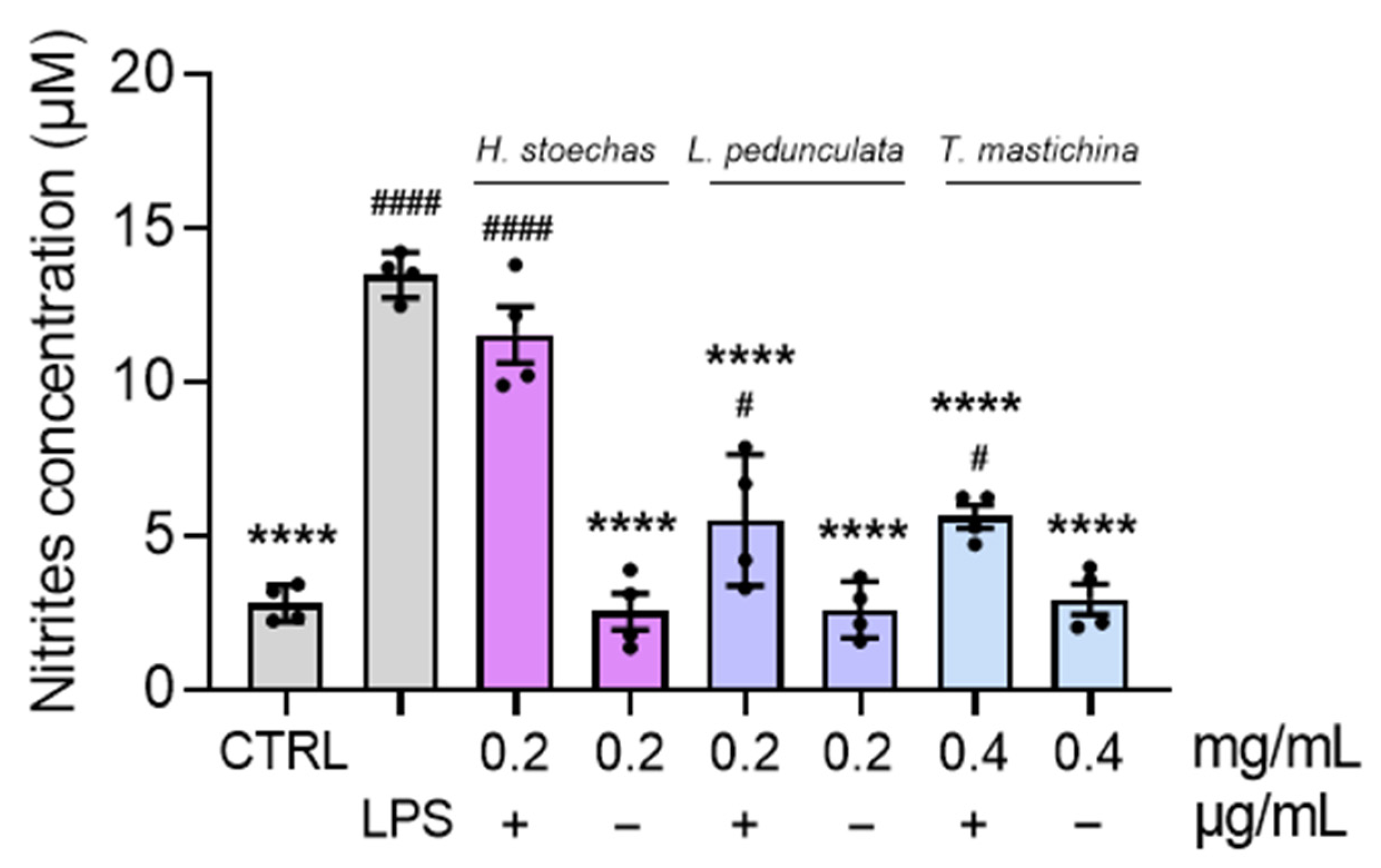

2.6. Effect on the Levels of Nitrites

2.7. Cell-Free Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitory Activity

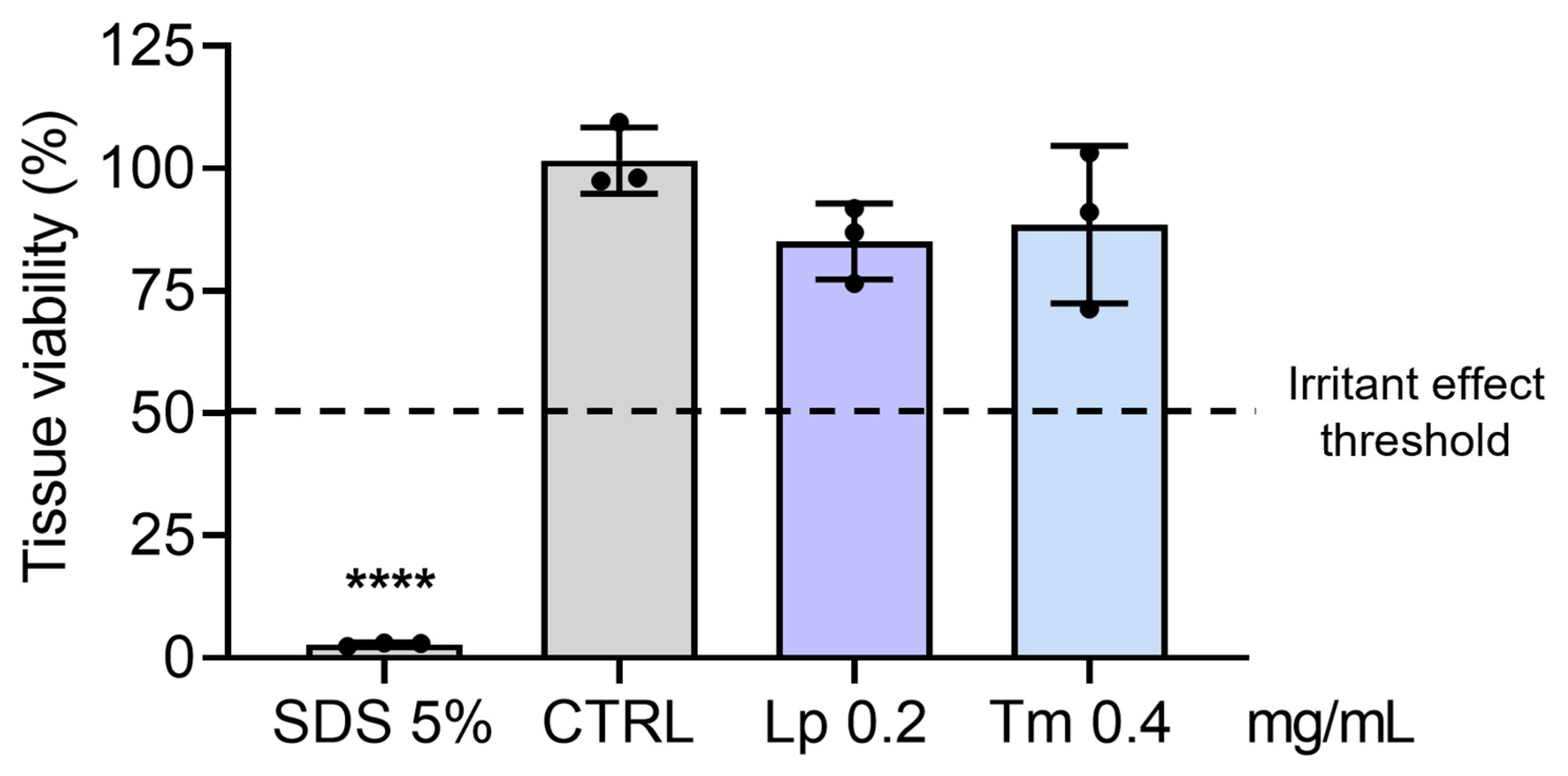

2.8. Skin Irritation Effects

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Chemicals

4.2. Plant Material

4.3. Hydroethanolic Extract Preparation

4.4. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy Analysis

4.5. HPLC–DAD–ESI/MSn Analysis

4.6. Major Phenolics Estimation and Cell-Free Antioxidant Activity Assessment

4.6.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

4.6.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay and Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC) Assay

4.6.3. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•) Radical and 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid) Radical Cation (ABTS•+) Scavenging Activity Assays

4.7. Cell Culture

4.8. Cell Metabolic Activity

4.9. Cell Mass

4.10. Cell-Free Enzymatic Inhibition Assays

4.10.1. Anti-Hyaluronidase Assay

4.10.2. Anti-Elastase Assay

4.10.3. Anti-Tyrosinase Assay

4.10.4. Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Assay

4.11. Measurement of Cellular Production of Nitrites

4.12. Evaluation of Cytoprotective Efficiency

4.13. Determination of Intracellular Oxidative Stress

4.14. Skin Irritation

4.15. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS•+ | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AVE | Herbarium of the University of Aveiro |

| BHT | Butylated hydroxytoluene |

| CUPRAC | Cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| DPPH• | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| DW | Dry weight |

| EGCG | (-)Epigallocatechin gallate |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| FTIR-ATR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| HaCaT | Immortalized human keratinocytes cell line |

| HE | Hydroethanolic extract (80:20%, v/v) (EtOH 80%) |

| HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with photodiode array detection and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry |

| H2DCFDA | 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| Hs | H. stoechas |

| KA | Kojic acid |

| LC | Liquid chromatography |

| Lp | L. pedunculata |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK/AP-1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase/activated protein-1 |

| min | Minutes |

| MS | Mass spectrometer |

| MTT | Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NHDF | Normal human dermal fibroblast cell line |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OH | Hydroxyl group |

| QE | Quercetin equivalents |

| RHE | Reconstructed human epidermis |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT | Room temperature |

| Rt | Retention time |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Sec | Seconds |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TE | Trolox equivalents |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| Tm | T. mastichina |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Marques, M.P.; Mendonça, L.; Neves, B.G.; Varela, C.; Oliveira, P.; Cabral, C. Exploring Iberian Peninsula Lamiaceae as Potential Therapeutic Approaches in Wound Healing. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant Extracts as Skin Care and Therapeutic Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Sousa, F.J.; Matos, P.; Brites, G.S.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Figueirinha, A.; Salgueiro, L.; Batista, M.T.; Branco, P.C.; et al. Chemical Composition and Effect against Skin Alterations of Bioactive Extracts Obtained by the Hydrodistillation of Eucalyptus globulus Leaves. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.F.; Magalhães, W.V.; Di Stasi, L.C. Recent Advances in Herbal-Derived Products with Skin Anti-Aging Properties and Cosmetic Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansinhos, I.; Gonçalves, S.; Rodríguez-Solana, R.; Luis Ordóñez-Díaz, J.; Manuel Moreno-Rojas, J.; Romano, A.; Barba, F.J. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Combination: A Green Strategy to Improve the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Lavandula pedunculata subsp. lusitanica (Chaytor) Franco. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Sezgin-Bayindir, Z.; Losada-Barreiro, S.; Paiva-Martins, F.; Saso, L.; Bravo-Díaz, C. Polyphenols as Antioxidants for Extending Food Shelf-Life and in the Prevention of Health Diseases: Encapsulation and Interfacial Phenomena. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.; Cagide, F.; Simões, J.; Pita, C.; Pereira, E.; Videira, A.J.C.; Soares, P.; Duarte, J.F.S.; Santos, A.M.S.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. Targeting Hydroxybenzoic Acids to Mitochondria as a Strategy to Delay Skin Ageing: An In Vitro Approach. Molecules 2022, 27, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Kucharska, E.; Kowalczyk, T.; Zajdel, K.; Cegliński, T.; Zajdel, R. Antioxidant Properties of Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Effect on Skin Fibroblast Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Hoian, U.; Czop, M.; Strzępek-Gomółka, M.; Antosiewicz, B. Characterization of Cistus × incanus L. and Cistus ladanifer L. Extracts as Potential Multifunctional Antioxidant Ingredients for Skin Protecting Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Marques, M.P.; Pinho, R.; Lopes, L.; Cabral, C. Guia da Flora do Vale do Côa, 1st ed.; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, R.; Marques, M.P.; Varela, C.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Teixeira, J.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cabral, C. Mechanistic Insights into Equisetum ramosissimum-Mediated Protection against Palmitic Acid-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in a Cell Model for Liver Steatosis. Food Biosci. 2025, 72, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R.; Marques, M.; Melim, C.; Varela, C.; Sardão, V.; Teixeira, J.; Dias, M.; Barros, L.; Oliveira, P.; Cabral, C. Chemical Characterization and Differential Lipid-Modulating Effects of Selected Plant Extracts from Côa Valley (Portugal) in a Cell Model for Liver Steatosis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, M.P.; Neves, B.G.; Varela, C.; Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Dias, M.I.; Amaral, J.S.; Barros, L.; Magalhães, M.; Cabral, C. Essential Oils from Côa Valley Lamiaceae Species: Cytotoxicity and Antiproliferative Effect on Glioblastoma Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjoun, M.; Kharchoufa, L.; Alami Merrouni, I.; Elachouri, M. Moroccan Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used for the Treatment of Skin Diseases: From Ethnobotany to Clinical Trials. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Rolo, J.; Gaspar, C.; Ramos, L.; Cavaleiro, C.; Salgueiro, L.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Teixeira, J.P.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A. Thymus mastichina (L.) L. and Cistus ladanifer L. for Skin Application: Chemical Characterization and in vitro Bioactivity Assessment. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 302, 115830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, G.; González-Tejero, M.R.; Molero-Mesa, J. Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in the Western Part of Granada Province (Southern Spain): Ethnopharmacological Synthesis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 129, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.A.; García-Barriuso, M.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, R.; Bernardos, S.; Amich, F. Plants Used in Folk Cosmetics and Hygiene in the Arribes Del Duero Natural Park (Western Spain). Lazaroa 2012, 33, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, J.; Delgado, F.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Zuzarte, M.; Duarte, A.P. Mediterranean Lavenders from Section Stoechas: An Undervalued Source of Secondary Metabolites with Pharmacological Potential. Metabolites 2023, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeosun, W.B.; Prinsloo, G. A Comprehensive Review on the Metabolomic Profiles, Pharmacological Properties, and Biological Activities of Helichrysum Species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 185, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, M.; Aldini, G.; Furlanetto, S.; Stefani, R.; Facino, R.M. LC Coupled to Ion-Trap MS for the Rapid Screening and Detection of Polyphenol Antioxidants from Helichrysum stoechas. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2001, 24, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, M.R.; Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Exploring the Antioxidant Potential of Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench Phenolic Compounds for Cosmetic Applications: Chemical Characterization, Microencapsulation and Incorporation into a Moisturizer. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 53, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Cvetanović, A.; Gašić, U.; Tešić, Ž.; Stupar, A.; Bulut, G.; Sinan, K.I.; Uysal, S.; Picot-Allain, M.C.N.; Mahomoodally, M.F. A Comparative Exploration of the Phytochemical Profiles and Bio-Pharmaceutical Potential of Helichrysum stoechas Subsp. barrelieri Extracts Obtained via Five Extraction Techniques. Process Biochem. 2020, 91, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les, F.; Venditti, A.; Cásedas, G.; Frezza, C.; Guiso, M.; Sciubba, F.; Serafini, M.; Bianco, A.; Valero, M.S.; López, V. Everlasting Flower (Helichrysum stoechas Moench) as a Potential Source of Bioactive Molecules with Antiproliferative, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Neuroprotective Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.L.; Pereira, E.; Soković, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Barata, A.M.; Lopes, V.; Rocha, F.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Composition and Bioactivity of Lavandula pedunculata (Mill.) Cav. Samples from Different Geographical Origin. Molecules 2018, 23, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Goméz-García, R.; Machado, M.; Nunes, C.; Ribeiro, S.; Nunes, J.; Oliveira, A.L.S.; Pintado, M. Lavandula pedunculata Polyphenol-Rich Extracts Obtained by Conventional, MAE and UAE Methods: Exploring the Bioactive Potential and Safety for Use a Medicine Plant as Food and Nutraceutical Ingredient. Foods 2023, 12, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Abu-Darwish, M.S.; Tarawneh, A.H.; Cabral, C.; Gadetskaya, A.V.; Salgueiro, L.; Hosseinabadi, T.; Rajabi, S.; Chanda, W.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; et al. Thymus spp. Plants—Food Applications and Phytopharmacy Properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 85, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Lopes, A.C.; Vaz, F.; Filipe, M.; Alves, G.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Coutinho, P.; Araujo, A.R.T.S. Thymus mastichina: Composition and Biological Properties with a Focus on Antimicrobial Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Tovar, I.; Sponza, S.; Asensio-S-Manzanera, M.C.; Novak, J. Contribution of the Main Polyphenols of Thymus mastichina subsp. mastichina to Its Antioxidant Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 66, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghouti, M.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Schäfer, J.; Santos, J.A.; Bunzel, M.; Nunes, F.M.; Silva, A.M. Chemical Characterization and Bioactivity of Extracts from Thymus mastichina: A Thymus with a Distinct Salvianolic Acid Composition. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, T.; Marinero, P.; Asensio-S.-Manzanera, M.C.; Asensio, C.; Herrero, B.; Pereira, J.A.; Ramalhosa, E. Antioxidant Activity of Twenty Wild Spanish Thymus mastichina L. Populations and Its Relation with Their Chemical Composition. LWT 2014, 57, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, R.M.F.; Bosch, M.; Simister, R.; Gomez, L.D.; Canhoto, J.M.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E. Valorisation Potential of Invasive Acacia Dealbata, A. longifolia and A. melanoxylon from Land Clearings. Molecules 2022, 27, 7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.J.S.; Santos, J.A.V.; Pinto, J.C.N.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Castilho, P.C.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E.; Marques, M.P.M.; Barroca, M.J.; Moreira da Silva, A.; da Costa, R.M.F. Spectrochemical Analysis of Seasonal and Sexual Variation of Antioxidants in Corema album (L.) D. Don Leaf Extracts. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 299, 122816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Method; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 9789264242845.

- Baranović, G.; Šegota, S. Infrared Spectroscopy of Flavones and Flavonols. Reexamination of the Hydroxyl and Carbonyl Vibrations in Relation to the Interactions of Flavonoids with Membrane Lipids. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 192, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Baró, A.C.; Parajón-Costa, B.S.; Franca, C.A.; Pis-Diez, R. Theoretical and Spectroscopic Study of Vanillic Acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 889, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Prieto, P.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Maria, T.M.R.; Hernández-Navarro, S.; Garrido-Laurnaga, F.; Eusébio, M.E.S.; Martín-Gil, J. Vibrational and Thermal Studies of Essential Oils Derived from Cistus ladanifer and Erica arborea Shrubs. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.; Lopes, T.; Correia, S.; Canhoto, J.; Marques, M.P.M.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E. Nutraceutical Properties of Tamarillo Fruits: A Vibrational Study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 252, 119501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; ur Rehman, D.I. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świsłocka, R.; Kowczyk-Sadowy, M.; Kalinowska, M.; Lewandowski, W. Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, 1H and 13C NMR) and Theoretical Studies of p-Coumaric Acid and Alkali Metal p-Coumarates. Spectroscopy 2012, 27, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.-L.; Lee, K.K.-H.; Kok, S.H.-L.; Cheng, G.Y.-M.; Tao, X.-M.; Hau, D.K.-P.; Yuen, M.C.-W.; Lam, K.-H.; Gambari, R.; Chui, C.-H.; et al. Development of Formaldehyde-Free Agar/Gelatin Microcapsules Containing Berberine HCl and Gallic Acid and Their Topical and Oral Applications. Soft Matter. 2012, 8, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.; Oliveira, C.; Amorim, R.; Cagide, F.; Garrido, J.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Pereira, C.M.; Silva, A.F.; Andrade, P.B.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. Development of Hydroxybenzoic-Based Platforms as a Solution to Deliver Dietary Antioxidants to Mitochondria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chong, L.; Huang, T.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, H. Natural Products and Extracts from Plants as Natural UV Filters for Sunscreens: A Review. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2023, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.P.; Martin, D.; Bosch, M.; Martins, J.; Biswal, A.; Zuzarte, M.; de Carvalho, L.B.; Canhoto, J.; da Costa, R. Unveiling the Compositional Remodelling of Arbutus unedo L. Fruits during Ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansinhos, I.; Gonçalves, S.; Rodríguez-Solana, R.; Duarte, H.; Ordóñez-Díaz, J.L.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M.; Romano, A. Response of Thymus lotocephalus in vitro Cultures to Drought Stress and Role of Green Extracts in Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Shahzad, N.; Kim, C.K. Structure-Antioxidant Activity Relationship of Methoxy, Phenolic Hydroxyl, and Carboxylic Acid Groups of Phenolic Acids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, N.; Santiago, A.; Alías, J.C. Quantification of the Antioxidant Activity of Plant Extracts: Analysis of Sensitivity and Hierarchization Based on the Method Used. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, S.; Morgado, M.; Plácido, A.I.; Roque, F.; Duarte, A.P. Arbutus Unedo L.: From Traditional Medicine to Potential Uses in Modern Pharmacotherapy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, S.; Piçarra, A.; Candeias, F.; Caldeira, A.T.; Martins, M.R.; Teixeira, D. Antioxidant Activity and Cholinesterase Inhibition Studies of Four Flavouring Herbs from Alentejo. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2183–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Lamiaceae Often Used in Portuguese Folk Medicine as a Source of Powerful Antioxidants: Vitamins and Phenolics. LWT 2010, 43, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.; Pasko, P.; Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Szewczyk, A.; Szlosarczyk, M.; Carvalho, I.S. Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Properties and Zinc Content of Five South Portugal Herbs. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Madroñal, M.; Caro-León, J.; Espinosa-Cano, E.; Aguilar, M.R.; Vázquez-Lasa, B. Chitosan—Rosmarinic Acid Conjugates with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Photoprotective Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Gonçalves, S.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Almeida, C.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Romano, A. Metabolic Profile and Biological Activities of Lavandula pedunculata subsp. lusitanica (Chaytor) Franco: Studies on the Essential Oil and Polar Extracts. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Spínola, V.; Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. HPLC-ESI-MSn Characterization of Phenolic Compounds, Terpenoid Saponins, and Other Minor Compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 69, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Gomes, C.; Taghouti, M.; Schäfer, J.; Bunzel, M.; Silva, A.M.; Nunes, F.M. Chemical Characterization and Bioactive Properties of Decoctions and Hydroethanolic Extracts of Thymus carnosus Boiss. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 43, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinska, A.; Sodagam, L.; Bloniarz, D.; Siems, K.; Wnuk, M.; Rattan, S.I.S. Plant-Derived Molecules α-Boswellic Acid Acetate, Praeruptorin-A, and Salvianolic Acid-B Have Age-Related Differential Effects in Young and Senescent Human Fibroblasts In Vitro. Molecules 2020, 25, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Zhao, M.M.; Yang, R.Y.; Deng, X.F.; Zhang, H.Y.; Choi, Y.M.; An, I.S.; An, S.K.; Dong, Y.M.; He, Y.F.; et al. Salvianolic Acid B Regulates Collagen Synthesis: Indirect Influence on Human Dermal Fibroblasts through the Microvascular Endothelial Cell Pathway. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3007–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L. Potential Beneficial Effects of Salvianic Acid A and Salvianolic Acid B in Skin Whitening. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X231219604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Park, S.Y.; Hwang, E.; Zhang, M.; Jin, F.; Zhang, B.; Yi, T.H. Salvianolic Acid B Protects Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Against Ultraviolet B Irradiation-Induced Photoaging Through Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Activator Protein-1 Pathways. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, W.; Mu, Y.P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.N.; Zhao, C.Q.; Chen, J.M.; Liu, P. Pharmacological Effects of Salvianolic Acid B Against Oxidative Damage. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 572373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Silva, J.M.; Pedreiro, S.; Cavaleiro, C.; Cruz, M.T.; Figueirinha, A.; Salgueiro, L. Effect of Thymbra capitata (L.) Cav. on Inflammation, Senescence and Cell Migration. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako-Bonsu, A.G.; Chan, S.L.; Pratten, M.; Fry, J.R. Antioxidant Activity of Rosmarinic Acid and Its Principal Metabolites in Chemical and Cellular Systems: Importance of Physico-Chemical Characteristics. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 40, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.J.; Kim, K.B.; An, I.S.; Ahn, K.J.; Han, H.J. Protective Effects of Rosmarinic Acid against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Cellular Senescence and the Inflammatory Response in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 9763–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicka, A.; Sutkowska-Skolimowska, J. The Beneficial Effect of Rosmarinic Acid on Benzophenone-3-Induced Alterations in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwiejczuk, N.; Galicka, A.; Zaręba, I.; Brzóska, M.M. The Protective Effect of Rosmarinic Acid against Unfavorable Influence of Methylparaben and Propylparaben on Collagen in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Park, S.Y.; Hwang, E.; Zhang, M.; Seo, S.A.; Lin, P.; Yi, T.H. Thymus Vulgaris Alleviates UVB Irradiation Induced Skin Damage via Inhibition of MAPK/AP-1 and Activation of Nrf2-ARE Antioxidant System. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamatsu, S.; Takano, K.; Aoki, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Suzuki, T. Rosemary Extract and Rosmarinic Acid Accelerate Elastic Fiber Formation by Increasing the Expression of Elastic Fiber Components in Dermal Fibroblasts. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.m.; Liu, Y.x.; Liu, Y.d.; Ho, C.k.; Tsai, Y.T.; Wen, D.s.; Huang, L.; Zheng, D.n.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.f.; et al. Salvianolic Acid B Protects against UVB-Induced Skin Aging via Activation of NRF2. Phytomedicine 2024, 130, 155676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, N.; Hauck, C.; Yum, M.Y.; Rizshsky, L.; Widrlechner, M.P.; McCoy, J.A.; Murphy, P.A.; Dixon, P.M.; Nikolau, B.J.; Birt, D.F. Rosmarinic Acid in Prunella vulgaris Ethanol Extract Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Lnduced Prostaglandin E2 and Nitric Oxide in RAW 264.7 Mouse Macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10579–10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.M.; Domínguez-Martín, E.M.; Nicolai, M.; Faustino, C.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Rijo, P. Screening the Dermatological Potential of Plectranthus Species Components: Antioxidant and Inhibitory Capacities over Elastase, Collagenase and Tyrosinase. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiyana, W.; Chansakaow, S.; Intasai, N.; Kiattisin, K.; Lee, K.H.; Lin, W.C.; Lue, S.C.; Leelapornpisid, P. Chemical Constituents, Antioxidant, Anti-MMPs, and Anti-Hyaluronidase Activities of Thunbergia laurifolia Lindl. Leaf Extracts for Skin Aging and Skin Damage Prevention. Molecules 2020, 25, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falé, P.L.; Borges, C.; Madeira, P.J.A.; Ascensão, L.; Araújo, M.E.M.; Florêncio, M.H.; Serralheiro, M.L.M. Rosmarinic Acid, Scutellarein 4′-Methyl Ether 7-O-Glucuronide and (16S)-Coleon E Are the Main Compounds Responsible for the Antiacetylcholinesterase and Antioxidant Activity in Herbal Tea of Plectranthus barbatus (“falso Boldo”). Food Chem. 2009, 114, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants of The World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- da Costa, R.M.F.; Barrett, W.; Carli, J.; Allison, G.G. Analysis of Plant Cell Walls by Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. In The Plant Cell Wall. Methods in Molecular Biology; Popper, Z., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2149, pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, M.P.; Martins, J.; de Carvalho, L.A.E.B.; Zuzarte, M.R.; da Costa, R.M.F.; Canhoto, J. Study of Physiological and Biochemical Events Leading to Vitrification of Arbutus unedo L. Cultured in Vitro. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2021, 35, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessada, S.M.F.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Coleostephus myconis (L.) Rchb.f.: An Underexploited and Highly Disseminated Species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 89, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.; Martin, D.; Amado, A.M.; Lysenko, V.; Osório, N.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E.; Marques, M.P.M.; Barroca, M.J.; da Silva, A.M. Novel Insights into Corema album Berries: Vibrational Profile and Biological Activity. Plants 2021, 10, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.S.G.; Starostina, I.G.; Ivanova, V.V.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pereira, S.P. Determination of Metabolic Viability and Cell Mass Using a Tandem Resazurin/Sulforhodamine B Assay. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2016, 2016, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichai, V.; Kirtikara, K. Sulforhodamine B Colorimetric Assay for Cytotoxicity Screening. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasooriya, W.D.; Abeysekera, W.P.K.M.; Ratnasooriya, C.T.D. In Vitro Anti-Hyaluronidase Activity of Sri Lankan Low Grown Orthodox Orange Pekoe Grade Black Tea (Camellia sinensis L.). Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, S.A.; Costa, C.F.; Deus, C.M.; Pinho, S.L.C.; Miranda-Santos, I.; Afonso, G.; Bagshaw, O.; Stuart, J.A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cunha-Oliveira, T. Mitochondrial and Metabolic Remodelling in Human Skin Fibroblasts in Response to Glucose Availability. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5198–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H. stoechas | ||||||

| Peak | Rt | λmax | [M-H]− | MSn | Tentative Identification | Quantification |

| 1Hs | 4.80 | 325 | 353 | MS2: 191(100); MS3: 179(35), 173(>5), 161(5), 135(7) | 1-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 1.52 ± 0.05 |

| 2Hs | 7.28 | 326 | 353 | MS2: 191(100); MS3: 179(>5), 173(135), 111(100) | 4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 15.95 ± 0.93 |

| 3Hs | 8.78 | 319 | 353 | MS2: 191(100); MS3: 179(>5), 173(100), 111(10) | 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 0.91 ± 0.04 |

| 4Hs | 10.53 | 320 | 179 | MS2: 161(100), 135(25) | Caffeic acid | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

| 5Hs | 13.69 | 328 | 367 | MS2: 191(100); MS3: 173(56), 127(100) | 5-O-Feruloylquinic acid | 0.52 ± 0.02 |

| 6Hs | 15.02 | 355 | 479 | MS2: 317(100) | Myricetin-3-O-hexoside | 4.47 ± 0.02 |

| 7Hs | 16.32 | 321 | 873 | MS2: 829(44), 625(100); MS3: 479(100), 317(23) | Quercetagetin 3-O-(malonylcoumaroyl)- hexoside-7-O-hexoside isomer I | 2.73 ± 0.01 |

| 8Hs | 16.71 | 322 | 787 | MS2: 625(100); MS3: 479(100), 317(23) | Quercetagetin-O-coumaroyl- hexosyl-O-hexoside | 2.93 ± 0.03 |

| 9Hs | 17.16 | 323 | 461 | MS2: 317(100) | Quercetagetin or mirycetin derivative isomer I | 2.86 ± 0.00 |

| 10Hs | 17.79 | 320 | 873 | MS2: 829(44), 625(100); MS3: 479(100), 317(23) | Quercetagetin 3-O-(malonylcoumaroyl)- hexoside-7-O-hexoside isomer II | 5.35 ± 0.06 |

| 11Hs | 18.03 | 357 | 461 | MS2: 317(100) | Quercetagetin or mirycetin derivative isomer II | 10.79 ± 0.06 |

| 12Hs | 18.86 | 341 | 461 | MS2: 317(100) | Quercetagetin or mirycetin derivative isomer III | 3.57 ± 0.01 |

| 13Hs | 19.12 | 335 | 463 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 2.43 ± 0.11 |

| 14Hs | 20.29 | 347 | 549 | MS2: 505(100), 301(23) | Quercetin-O-malonyl-hexoside isomer I | 1.29 ± 0.02 |

| 15Hs | 20.72 | 323 | 515 | MS2: 353(100), 335(<5); MS3: 191(100), 179(74), 173(<5), 161(14), 135(<5) | 3,5-O-diCaffeoylquinic acid | 10.18 ± 0.64 |

| 16Hs | 22.57 | 335 | 549 | MS2: 505(100), 301(23) | Quercetin-O-malonyl-hexoside isomer II | 1.49 ± 0.01 |

| 17Hs | 23.13 | 329 | 515 | MS2: 353(100), 335(26); MS3: 191(22), 179(31), 173(100) | 3,4-O-diCaffeoylquinic acid | 7.41 ± 0.02 |

| 18Hs | 23.62 | 341 | 515 | MS2: 353(100), 335(<5); MS3: 191(34), 179(9), 173(100), 135(6) | 4,5-O-diCaffeoylquinic acid | 2.45 ± 0.17 |

| 19Hs | 23.73 | 350 | 477 | MS2: 315(100) | Isorhamnetin-O-hexoside | 2.26 ± 0.01 |

| 20Hs | 24.76 | 329 | 601 | MS2: 557(100), 515(<5), 439(17), 395(763), 377(<5) | Malonyl-dicaffeoyl-quinic acid isomer | 2.20 ± 0.12 |

| 21Hs | 25.59 | 364 | 463 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-O-hexoside | 2.13 ± 0.07 |

| 22Hs | 26.07 | 343 | 563 | MS2: 519(100), 315(35) | Isorhamnetin-O-(-O-malonyl)-hexoside | 1.11 ± 0.01 |

| 23Hs | 27.72 | 364 | 549 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-dipentoside | 2.18 ± 0.06 |

| 24Hs | 29.50 | 332 | 727 | MS2: 683(100), 317(12) | Myricetin-O-malonyl-dihexoside | 3.15 ± 0.09 |

| 25Hs | 30.13 | 314 | 609 | MS2: 463(23), 301(100) | Quercetin 3-O-[p-coumaroyl]-hexoside | 2.47 ± 0.03 |

| 26Hs | 32.31 | 315 | 695 | MS2: 651(32), 100(>5), 301(34) | Quercetin-O-malony[p-coumarouyl]-deoxyhexoside | 0.75 ± 0.02 |

| 27Hs | 33.22 | 328 | 593 | MS2: 285(100) | Kaempherol-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer I | 0.93 ± 0.01 |

| 28Hs | 33.56 | 332 | 593 | MS2: 285(100) | Kaempherol-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer II | 0.92 ± 0.02 |

| 29Hs | 33.97 | 315 | 623 | MS2: 477(25), 315(100) | Isorhamentin-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside | 1.14 ± 0.04 |

| 30Hs | 35.17 | 315 | 679 | MS2: 635(12), 285(100) | Kaempherol-O-deoxyhexosyl-malonyl-hexoside | 0.86 ± 0.01 |

| Total phenolic compounds | 97.27 ± 2.33 a | |||||

| Total phenolic acids | 41.47 ± 1.75 b | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 55.80 ± 0.58 c | |||||

| L. pedunculata | ||||||

| Peak | Rt | λmax | [M-H]− | MSn | Tentative Identification | Quantification |

| 1Lp | 5.97 | 324 | 341 | MS2: 179(100), 135(12) | Caffeic acid hexoside | 0.53 ± 0.02 |

| 2Lp | 6.51 | 322 | 489 | MS2: 179(23), 161(100) | Caffeic acid derivative | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| 3Lp | 7 | 326 | 325 | MS2: 163(100) | p-Coumaroyl hexoside isomer I | 1.66 ± 0.06 |

| 4Lp | 7.25 | 324 | 325 | MS2: 163(100) | p-Coumaroyl hexoside isomer II | 1.16 ± 0.04 |

| 5Lp | 8.74 | 311 | 387 | MS2: 369(15), 207(100), 163(70) | Medioresinol | 1.44 ± 0.11 |

| 6Lp | 10.64 | 320 | 179 | MS2: 161(100), 135(25) | Caffeic acid | 1.26 ± 0.07 |

| 7Lp | 11.87 | 324 | 325 | MS2: 163(100) | p-Coumaroyl hexoside isomer III | 2.68 ± 0.05 |

| 9Lp | 15.28 | 320 | 357 | MS2: 151(12), 177(32), 195(100) | Trihydroxycinnamic acid-O-hexoside | 0.64 ± 0.01 |

| 10Lp | 16.22 | 284.326sh | 463 | MS2: 287(100) | Eriodyctiol-O-hexuronoside | 11.61 ± 0.37 |

| 11Lp | 17.44 | 319 | 521 | MS2: 359(100); MS3: 197(25), 179(46), 161(100), 135(5) | Rosmarinic acid hexoside | 6.39 ± 0.24 |

| 12Lp | 18.43 | 346 | 461 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-7-O- hexuronoside | 12.59 ± 0.57 |

| 13Lp | 19.17 | 344 | 447 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside | 3.96 ± 0.26 |

| 14Lp | 19.45 | 285.332sh | 719 | MS2: 539(33), 521(<5), 359(100); MS3: 197(87), 179(100), 161(54), 135(5) | Sangerinic acid | 3.99 ± 0.23 |

| 15Lp | 22.15 | 326 | 359 | MS2: 197(29), 179(34), 161(100) | Rosmarinic acid | 60.8 ± 0.21 |

| 16Lp | 22.95 | 335 | 445 | MS2: 269(100) | Apigenin-O-hexuronoside | 8.65 ± 0.45 |

| 17Lp | 23.42 | 334 | 431 | MS2: 269(100) | Apigenin-O-hexoside | 4.28 ± 0.24 |

| 18Lp | 23.84 | 338 | 533 | MS2: 489(100), 285(34) | Luteolin-O-malonyl-hexoside | 1.34 ± 0.02 |

| 19Lp | 24.37 | 344 | 475 | MS2: 299(100), 284(54) | Methylluteolin-O-hexuronoside | 4.31 ± 0.01 |

| 20Lp | 24.96 | 339 | 461 | MS2: 299(100), 284(32) | Methylluteolin-O-hexoside | 1.66 ± 0.07 |

| 21Lp | 25.61 | 311 | 717 | MS2: 537(100); MS3: 339(34), 321(100), 313(<5), 295(<5), 197(13) | Salvianolic acid B | 45.69 ± 0.46 |

| 22Lp | 28.29 | 331 | 473 | MS2: 269(100) | Apigenin-O-acetyl-hexoside | 7.81 ± 0.09 |

| 23Lp | 29.11 | 328 | 533 | MS2: 489(65), 285(100) | Luetolin-O-diacetyl-hexoside | 2.34 ± 0.02 |

| 26Lp | 32.49 | 326 | 623 | MS2: 285(00) | Luteolin-O-hexosyl-hexuronoside | 0.67 ± 0.03 |

| Total phenolic compounds | 186.34 ± 0.77 a | |||||

| Total phenolic acids | 127.14 ± 0.39 b | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 59.21 ± 0.38 c | |||||

| T. mastichina | ||||||

| Peak | Rt | λmax | [M-H]− | MSn | Tentative Identification | Quantification |

| 1Tm | 6.77 | 326 | 353 | MS2: 191(100); MS3: 179(>5), 173(135), 111(100) | 4-O-caffeoylquinic acid | 1.39 ± 0.09 |

| 2Tm | 8.82 | 255 | 387 | MS2: 369(87), 207(100), 163(12) | Hydroxyjasmonic | 0.27 ± 0.01 |

| 4Tm | 10.06 | 356 | 593 | MS2: 473(54), 383(38), 353(65) | Apigenin-C-dihexoside | 0.88 ± 0.02 |

| 5Tm | 10.6 | 323 | 179 | MS2: 161(100), 135(25) | Caffeic acid | 0.96 ± 0.02 |

| 6Tm | 11.45 | 284 | 449 | MS2: 287(100) | Eriodyctiol-O-hexoside isomer I | 1.43 ± 0.01 |

| 7Tm | 12.89 | 284 | 449 | MS2: 287(100) | Eriodyctiol-O-hexoside isomer II | 3.69 ± 0.10 |

| 8Tm | 15.92 | 353 | 463 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-O-hexoside isomer I | 15.23 ± 0.23 |

| 9Tm | 16.47 | 343 | 463 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-O-hexoside isomer II | 3.32 ± 0.02 |

| 10Tm | 16.97 | 342 | 447 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer I | 1.38 ± 0.09 |

| 11Tm | 17.13 | 282/324 | 433 | MS2: 271(100) | Naringenin-O-hexoside | 2.73 ± 0.10 |

| 12Tm | 17.5 | 319 | 521 | MS2: 359(100); MS3: 197(25), 179(46), 161(100), 135(5) | Rosmarinic acid hexoside | 1.63 ± 0.10 |

| 14Tm | 19.15 | 350 | 447 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer II | 9.42 ± 0.38 |

| 15Tm | 19.29 | 343 | 447 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer III | 7.10 ± 0.49 |

| 16Tm | 21.07 | 334 | 449 | MS2: 287(100) | Eriodyctiol-O-hexoside isomer III | 1.41 ± 0.05 |

| 17Tm | 21.59 | 338 | 555 | MS2: 493(100), 359(23) | Salvianolic acid K isomer I | 3.30 ± 0.15 |

| 18Tm | 22.05 | 341 | 555 | MS2: 493(100), 359(23) | Salvianolic acid K isomer II | 3.94 ± 0.04 |

| 19Tm | 22.32 | 320 | 359 | MS2: 197(29), 179(34), 161(100) | Rosmarinic acid | 36.64 ± 0.50 |

| 20Tm | 23 | 331 | 555 | MS2: 493(100), 359(23) | Salvianolic acid K isomer III | 3.19 ± 0.01 |

| 21Tm | 23.46 | 335 | 431 | MS2: 269(100) | Apigenin-O-hexoside | 6.02 ± 0.35 |

| 22Tm | 23.69 | 332 | 717 | MS2: 555(20), 519(100), 475(12), 357(32) | Salvianolic acid B/E | 8.62 ± 0.33 |

| 23Tm | 25.55 | 335 | 475 | MS2: 299(100) | Chrysoeriol-O-hexuronoside | 0.99 ± 0.01 |

| 24Tm | 26.09 | 343 | 497 | MS2: 299(100) | Chrysoeriol derivative | 1.23 ± 0.06 |

| 25Tm | 26.7 | 336 | 639 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-O-hexoside-hexuronoside | 2.86 ± 0.09 |

| 26Tm | 27.79 | 319 | 609 | MS2: 301(100) | Quercetin-O-hexosyl-deoxyhexoside | 1.23 ± 0.03 |

| 28Tm | 29.17 | 330 | 609 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-dihexoside | 1.31 ± 0.12 |

| 29Tm | 29.95 | 331 | 623 | MS2: 285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside-hexuronoside | 1.72 ± 0.06 |

| 30Tm | 32.58 | 344 | 285 | - | Luteolin | 1.76 ± 0.04 |

| 31Tm | 35.1 | 289 | 271 | - | Naringenin | 1.52 ± 0.02 |

| 32Tm | 37.51 | 335 | 269 | - | Apigenin | 3.42 ± 0.09 |

| Total phenolic compounds | 128.60 ± 0.40 a | |||||

| Total phenolic acids | 59.95 ± 0.48 b | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 68.64 ± 0.07 c | |||||

| Hyaluronidase | Tyrosinase | Elastase | Acetylcholinesterase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hs (0.2 mg/mL) | 17.46 ± 6.88 **** | 65.01 ± 7.96 **** | 29.24 ± 7.15 **** | n.a. |

| Lp (0.2 mg/mL) | 79.86 ± 6.70 * | 64.15 ± 6.02 **** | n.a. | n.a. |

| Tm (0.4 mg/mL) | 91.52 ± 4.19 | 62.65 ± 6.98 **** | 28.85 ± 5.65 **** | 27.37 ± 4.92 **** |

| Positive control a | 98.76 ± 8.20 | 93.31 ± 5.53 | 68.17 ± 5.51 | 93.97 ± 3.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, M.P.; Landim, E.; Varela, C.; da Costa, R.M.F.; Marques, J.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E.; Silva, A.; Cruz, M.T.; André, R.; Rijo, P.; et al. A Spectrochemically Driven Study: Identifying Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Helichrysum stoechas, Lavandula pedunculata, and Thymus mastichina with Potential to Revert Skin Aging Effects. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121889

Marques MP, Landim E, Varela C, da Costa RMF, Marques J, Batista de Carvalho LAE, Silva A, Cruz MT, André R, Rijo P, et al. A Spectrochemically Driven Study: Identifying Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Helichrysum stoechas, Lavandula pedunculata, and Thymus mastichina with Potential to Revert Skin Aging Effects. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121889

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Mário Pedro, Euclides Landim, Carla Varela, Ricardo M. F. da Costa, Joana Marques, Luís A. E. Batista de Carvalho, Ana Silva, Maria Teresa Cruz, Rebeca André, Patrícia Rijo, and et al. 2025. "A Spectrochemically Driven Study: Identifying Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Helichrysum stoechas, Lavandula pedunculata, and Thymus mastichina with Potential to Revert Skin Aging Effects" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121889

APA StyleMarques, M. P., Landim, E., Varela, C., da Costa, R. M. F., Marques, J., Batista de Carvalho, L. A. E., Silva, A., Cruz, M. T., André, R., Rijo, P., Dias, M. I., Carvalho, A., Oliveira, P. J., & Cabral, C. (2025). A Spectrochemically Driven Study: Identifying Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Helichrysum stoechas, Lavandula pedunculata, and Thymus mastichina with Potential to Revert Skin Aging Effects. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121889