Berberine: A Rising Star in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Novel Insights into Its Anti-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Role of Berberine in T2DM Therapy

2.1. Regulation of Glucose Metabolism by Berberine

2.2. Regulation of Glucose Transport by Berberine

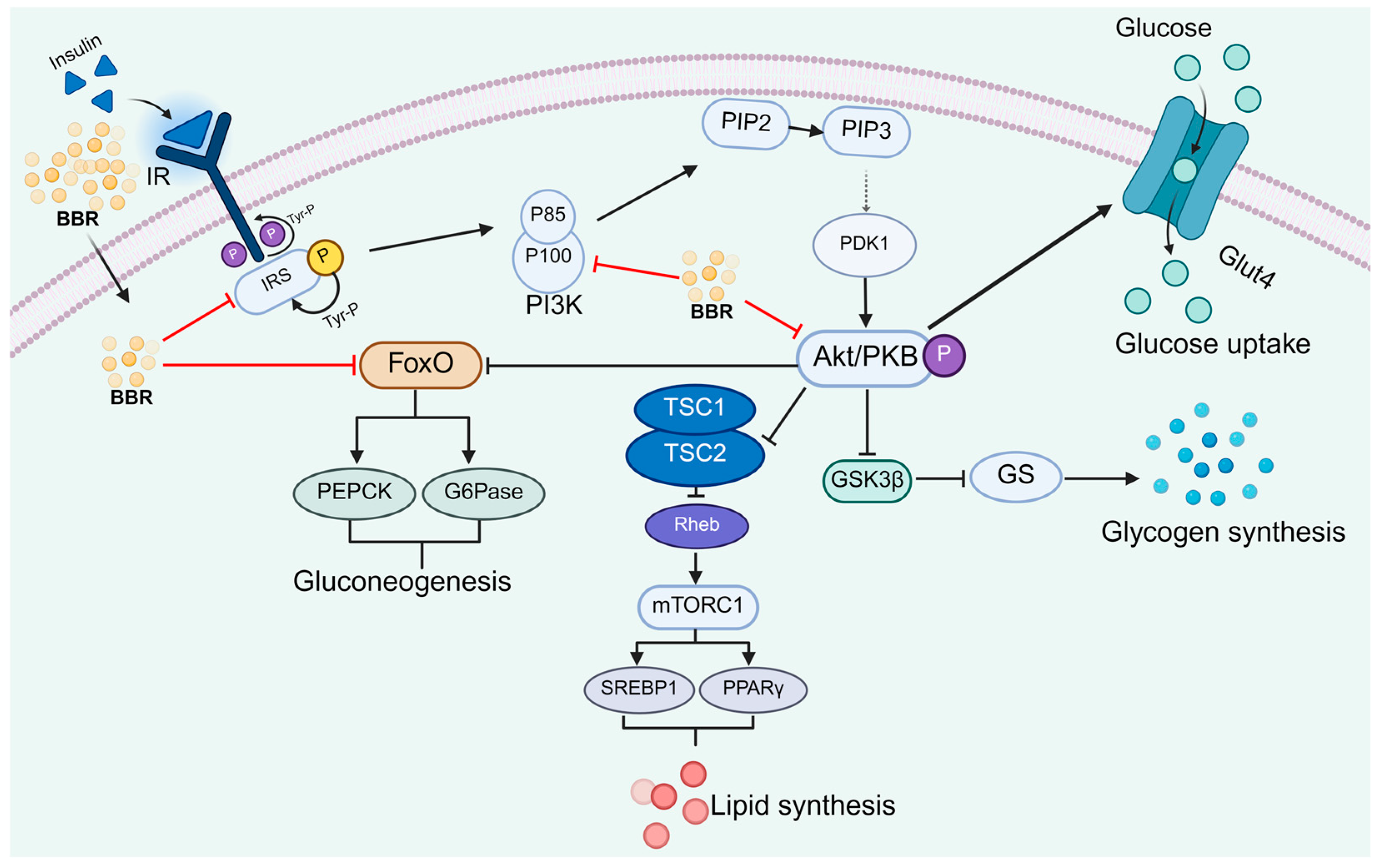

2.3. Regulation of the Insulin Signaling Pathway by Berberine

2.4. Berberine Induces the Secretion of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1)

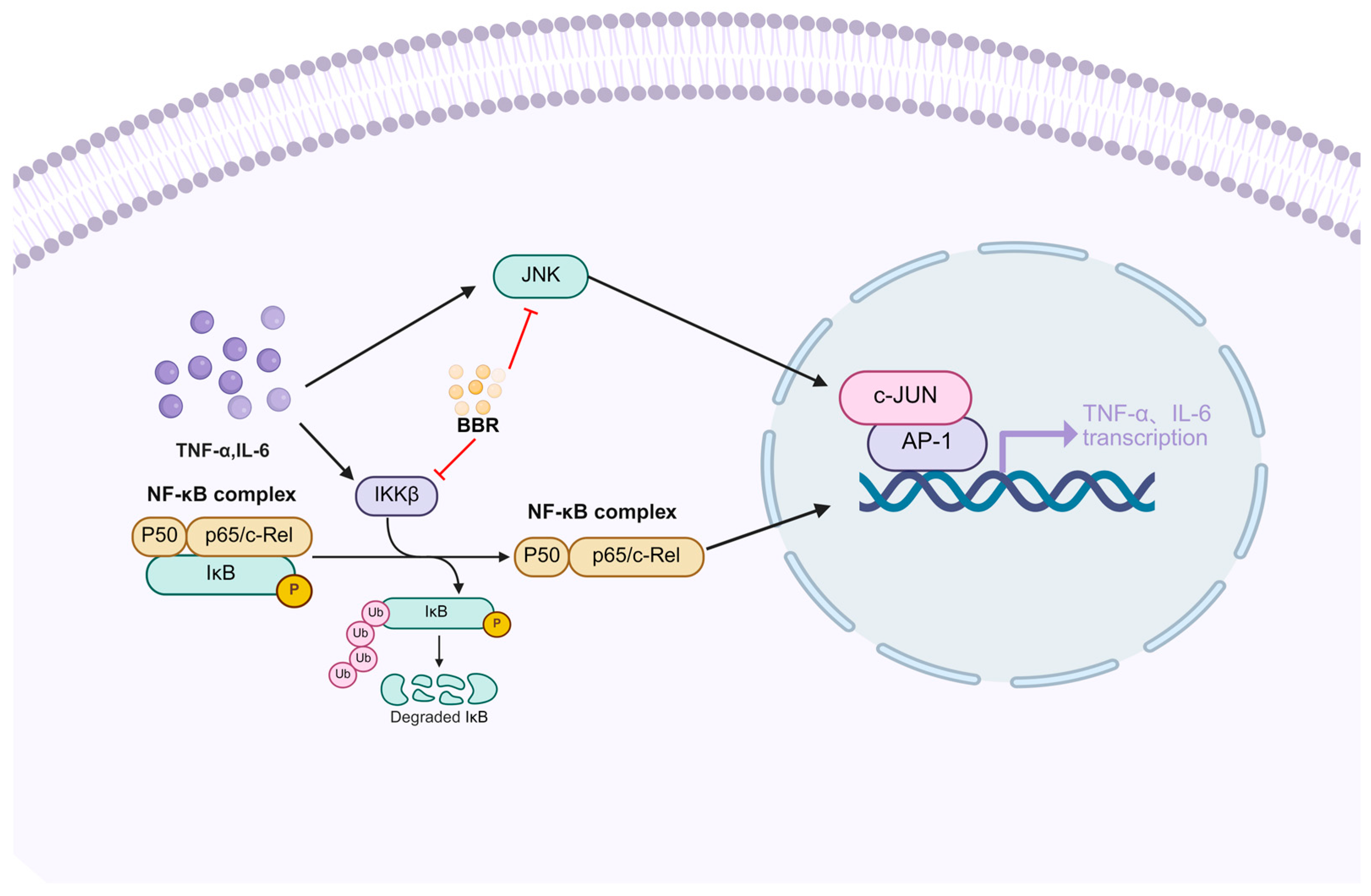

2.5. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of Berberine

2.6. Berberine Ameliorates Type 2 Diabetes Through Multi-Target Epigenetic Regulation

2.7. Protective Effects of Berberine on Pancreatic β-Cells and Promotion of Insulin Secretion

3. Mechanisms and Effects of Berberine Combination Therapy

| Drug Combinations | In Vitro and In Vivo Models | Mechanisms of Action and Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | Insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 cells | Inhibit inflammation | [167] |

| HFD/STZ-induced diabetic rat model | Improve glucose metabolism and alleviate insulin resistance | [168] | |

| Probiotics | Patients | Reduce blood glucose levels | [20,170] |

| Stachyose | High-fat diet (HFD)-induced diabetic mouse model; db/db mice | Reduce blood glucose levels | [172,173] |

| Timosaponin B2 | Spontaneously diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats | Reduce blood glucose levels | [175] |

| Astragalus polysaccharide | High-fat diet (HFD)-induced diabetic mouse model | Down-regulating FOXO1 phosphorylation and PEPCK expression, and up-regulating GLUT2 | [177] |

4. Clinical Research on the Application of Berberine

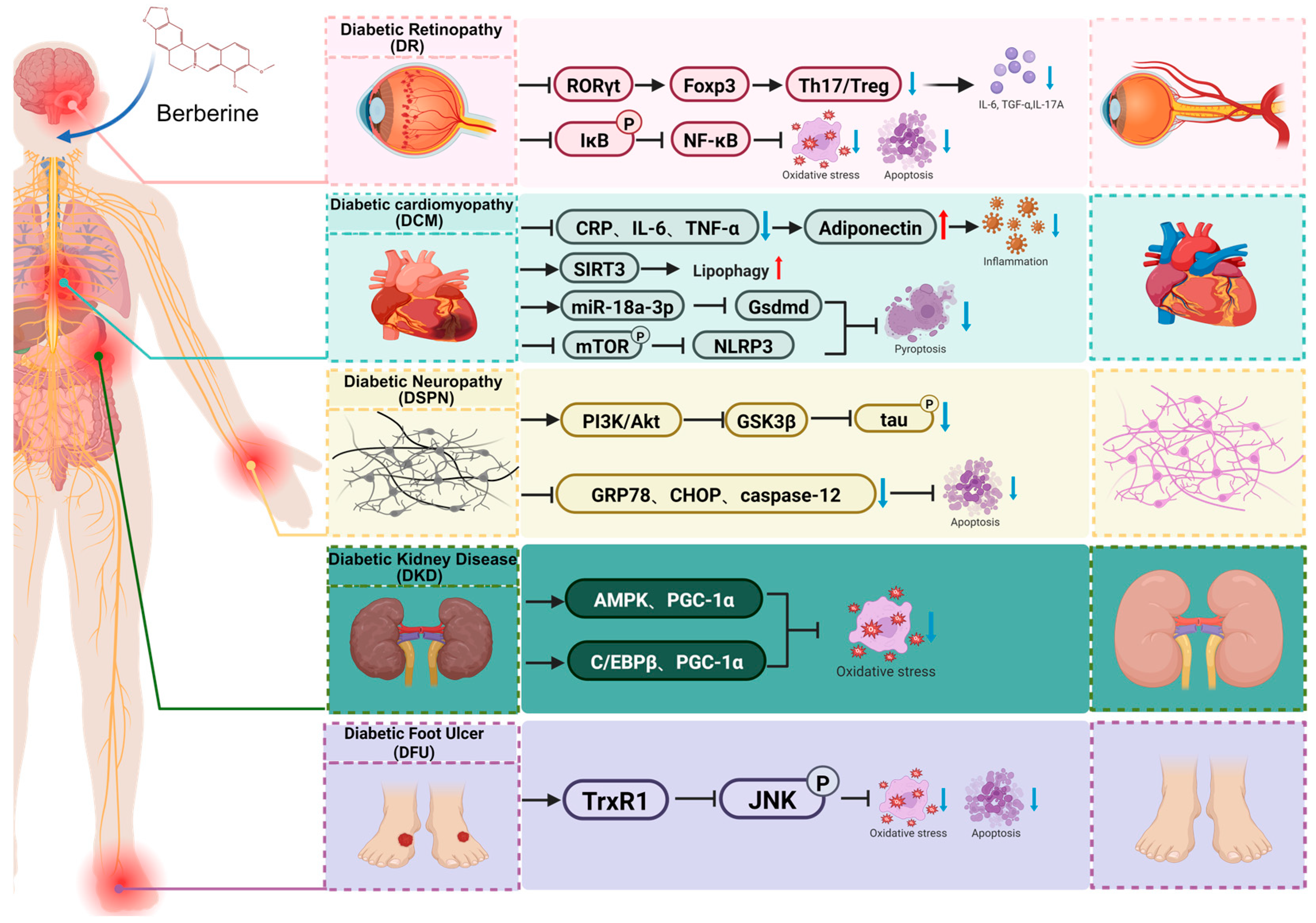

5. Protective Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of Berberine Against Diabetic Complications

5.1. Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD)

5.2. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

5.3. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy (DCM)

5.4. Diabetic Neuropathy (DSPN)

5.5. Diabetic Foot Ulcer (DFU)

6. Discussion and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Młynarska, E.; Czarnik, W.; Dzieża, N.; Jędraszak, W.; Majchrowicz, G.; Prusinowski, F.; Stabrawa, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: New Pathogenetic Mechanisms, Treatment and the Most Important Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, Regional and Country-Level Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2021 and Projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumvoll, M.; Goldstein, B.J.; Van Haeften, T.W. Type 2 Diabetes: Principles of Pathogenesis and Therapy. Lancet 2005, 365, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautzky-Willer, A.; Harreiter, J.; Pacini, G. Sex and Gender Differences in Risk, Pathophysiology and Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 278–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Acosta, J.; Schultz, G.S.; López-Mola, E.; Guillen-Nieto, G.; García-Siverio, M.; Herrera-Martínez, L. Glucose toxic effects on granulation tissue productive cells: The diabetics’ impaired healing. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 256043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C. Chronic hyperglycemia and glucose toxicity: Pathology and clinical sequelae. Postgrad. Med. 2012, 124, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony, R.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Drug Therapies for Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothai, S.; Ganesan, P.; Park, S.-Y.; Fakurazi, S.; Choi, D.-K.; Arulselvan, P. Natural Phyto-Bioactive Compounds for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Inflammation as a Target. Nutrients 2016, 8, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, R.; Ahmad, M.H.; Ghosh, B.; Mondal, A.C. Targeting NRF2 in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Depression: Efficacy of Natural and Synthetic Compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 925, 174993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbuna, C.; Awuchi, C.G.; Kushwaha, G.; Rudrapal, M.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Singh, O.; Odoh, U.E.; Khan, J.; Jeevanandam, J.; Kumarasamy, S.; et al. Bioactive Compounds Effective Against Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1067–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Resveratrol Therapy on Glucose Metabolism, Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Renal Function in the Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Protocol. Medicine 2022, 101, e30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahjabeen, W.; Khan, D.A.; Mirza, S.A. Role of Resveratrol Supplementation in Regulation of Glucose Hemostasis, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 66, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Li, D.; Hua, M.; Miao, X.; Su, Y.; Chi, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, R.; Niu, H.; Wang, J. Black Bean Husk and Black Rice Anthocyanin Extracts Modulated Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolites for Improvement in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7377–7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damián-Medina, K.; Milenkovic, D.; Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Corral-Jara, K.F.; Figueroa-Yáñez, L.; Marino-Marmolejo, E.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Anthocyanin-Rich Extract from Black Beans Exerts Anti-Diabetic Effects in Rats through a Multi-Genomic Mode of Action in Adipose Tissue. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1019259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Och, A.; Podgórski, R.; Nowak, R. Biological Activity of Berberine—A Summary Update. Toxins 2020, 12, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Hao, J.; Fan, D. Biological Properties and Clinical Applications of Berberine. Front. Med. 2020, 14, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Xing, H.; Ye, J. Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Metabolism 2008, 57, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Lou, W.; Zhang, P.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.J. The Effect of Berberine on Metabolic Profiles in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2074610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, S.; Zhong, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, J.; Gu, X.; Xue, Y.; Huang, S.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Related Effects of Berberine and Probiotics on Type 2 Diabetes (the PREMOTE Study). Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, S.; Wells, K.; Tribett, T.; El-Gharbawy, A. Glycogen Metabolism and Glycogen Storage Disorders. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, J.-W.; Ho, W.-K. Cellular and Systemic Mechanisms for Glucose Sensing and Homeostasis. Pflug. Arch.—Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, S.; Bai, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Ye, X.; Guo, C.; Chen, Y. Glycogen Synthesis Is Required for Adaptive Thermogenesis in Beige Adipose Tissue and Affects Diet-Induced Obesity. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E696–E708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, N.J.; Whitfield, J.; Janzen, N.R.; Belhaj, M.R.; Galic, S.; Murray-Segal, L.; Smiles, W.J.; Ling, N.X.Y.; Dite, T.A.; Scott, J.W.; et al. Genetic Loss of AMPK-Glycogen Binding Destabilises AMPK and Disrupts Metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2020, 41, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.T.; Betts, J.A. Dietary Sugars, Exercise and Hepatic Carbohydrate Metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 78, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, Z.; Liu, K.; Li, L.; Liu, B.; Huang, F. Berberine Inhibits Inflammatory Response and Ameliorates Insulin Resistance in Hepatocytes. Inflammation 2011, 34, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Jiang, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y. Berberine Ameliorates Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Regulating microRNA-146b/SIRT1 Pathway. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 2525–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Rumman, M.; Singh, B.; Mahdi, A.A.; Pandey, S. Berberine Ameliorates Glucocorticoid-Induced Hyperglycemia: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mei, X.; Ren, Z.; Chen, S.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Dai, G. Comprehensive Insights into Berberine’s Hypoglycemic Mechanisms: A Focus on Ileocecal Microbiome in Db/Db Mice. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, W.; Lan, T.; Liu, W.; Peng, J.; Huang, K.; Huang, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, P.; Huang, H. Berberine Ameliorates Hyperglycemia in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic C57BL/6 Mice through Activation of Akt Signaling Pathway. Endocr. J. 2011, 58, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandar, C.C.; Sen, D.; Maity, A. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of GSK-3 Inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, J.C.; Favre, C.; Gomis, R.R.; Fernández-Novell, J.M.; García-Rocha, M.; De La Iglesia, N.; Cid, E.; Guinovart, J.J. Control of Glycogen Deposition. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.-M.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.-Y.; Wu, R.-Q.; Gu, Q.; Zhou, T. Hypoglycemic and Gut Microbiota-Modulating Effects of Pectin from Citrus Aurantium “Changshanhuyou” Residue in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 9088–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Shen, J.; Bai, M.; Xu, E. Berberine Attenuates Fructose-Induced Insulin Resistance by Stimulating the Hepatic LKB1/AMPK/PGC1α Pathway in Mice. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Wu, F.; Wu, W.; Dong, H.; Huang, Z.; Xu, L.; Lu, F.; Gong, J. Berberine Reduces Hepatic Ceramide Levels to Improve Insulin Resistance in HFD-Fed Mice by Inhibiting HIF-2α. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Cao, L.; Gasa, R.; Brady, M.J.; Sherry, A.D.; Newgard, C.B. Glycogen-Targeting Subunits and Glucokinase Differentially Affect Pathways of Glycogen Metabolism and Their Regulation in Hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matschinsky, F.M. Glucokinase as Glucose Sensor and Metabolic Signal Generator in Pancreatic β-Cells and Hepatocytes. Diabetes 1990, 39, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Q.; Lu, F.-E.; Leng, S.-H.; Fang, X.-S.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.-S.; Dong, L.-P.; Yan, Z.-Q. Facilitating Effects of Berberine on Rat Pancreatic Islets through Modulating Hepatic Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha Expression and Glucokinase Activity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zuo, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G. Berberine Alleviates Hyperglycemia by Targeting Hepatic Glucokinase in Diabetic Db/Db Mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, A.; Schmoll, D. Novel Concepts in Insulin Regulation of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E685–E692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Shih, C.-C. Antidiabetic and Hypolipidemic Activities of Eburicoic Acid, a Triterpenoid Compound from Antrodia Camphorata , by Regulation of Akt Phosphorylation, Gluconeogenesis, and PPARα in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 20462–20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Sullivan, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Gilbert, R.G.; Deng, B. Metformin and Berberine Suppress Glycogenolysis by Inhibiting Glycogen Phosphorylase and Stabilizing the Molecular Structure of Glycogen in Db/Db Mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 243, 116435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Kong, B.; Yang, N.; Cao, B.; Feng, D.; Yu, X.; Ge, C.; Feng, S.; Fei, F.; Huang, J.; et al. The Hypoglycemic Effect of Berberine and Berberrubine Involves Modulation of Intestinal Farnesoid X Receptor Signaling Pathway and Inhibition of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2021, 49, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, P.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, L.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, B. Berberine Attenuates Hyperglycemia by Inhibiting the Hepatic Glucagon Pathway in Diabetic Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6210526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guan, H.; Tan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Li, D. Enhanced Alleviation of Insulin Resistance via the IRS-1/Akt/FOXO1 Pathway by Combining Quercetin and EGCG and Involving miR-27a-3p and miR-96–5p. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 181, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomonte, J.; Richter, A.; Harbaran, S.; Suriawinata, J.; Nakae, J.; Thung, S.N.; Meseck, M.; Accili, D.; Dong, H. Inhibition of Foxo1 Function Is Associated with Improved Fasting Glycemia in Diabetic Mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E718–E728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchenell, P.M.; Chu, Q.; Monks, B.R.; Birnbaum, M.J. Hepatic Insulin Signalling Is Dispensable for Suppression of Glucose Output by Insulin in Vivo. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Li, N.; Song, Z.; Yin, J.; Lu, L.; et al. Spexin Alleviates Insulin Resistance and Inhibits Hepatic Gluconeogenesis via the FoxO1/PGC-1α Pathway in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Rats and Insulin Resistant Cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2815–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Yan, J.; Shen, Y.; Tang, K.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Liang, H.; Ye, J.; Weng, J. Berberine Improves Glucose Metabolism in Diabetic Rats by Inhibition of Hepatic Gluconeogenesis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksum, I.P.; Rustaman, R.; Deawati, Y.; Rukayadi, Y.; Utami, A.R.; Nafisa, Z.K. Study of the Antidiabetic Mechanism of Berberine Compound on FOXO1 Transcription Factor through Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Meng, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chang, W.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Sodium Caprate Augments the Hypoglycemic Effect of Berberine via AMPK in Inhibiting Hepatic Gluconeogenesis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 363, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.T.; Frederico, M.J.S.; Da Luz, G.; Cintra, D.E.; Ropelle, E.R.; Pauli, J.R.; Velloso, L.A. Acute Exercise Reduces Hepatic Glucose Production through Inhibition of the Foxo1/HNF-4α Pathway in Insulin Resistant Mice. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 2239–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Y.; Lan, X.; Yao, F.; Yan, X.; Chen, L.; Hatch, G.M. Berberine Attenuates Development of the Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Lipid Metabolism Disorder in Type 2 Diabetic Mice and in Palmitate-Incubated HepG2 Cells through Suppression of the HNF-4α miR122 Pathway. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altarejos, J.Y.; Montminy, M. CREB and the CRTC Co-Activators: Sensors for Hormonal and Metabolic Signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravnskjaer, K.; Madiraju, A.; Montminy, M. Role of the cAMP Pathway in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. In Metabolic Control; Herzig, S., Ed.; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 233, pp. 29–49. ISBN 978-3-319-29804-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Zheng, R.; Chang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gao, M.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J. Cyclocarya Paliurus Triterpenoids Suppress Hepatic Gluconeogenesis via AMPK-Mediated cAMP/PKA/CREB Pathway. Phytomedicine 2022, 102, 154175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Sha, W.; Chen, L.; Lei, T.; Liu, L. Berberine Inhibits Gluconeogenesis in Spontaneous Diabetic Rats by Regulating the AKT/MAPK/NO/cGMP/PKG Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 478, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Jiang, X. The Molecular Mechanism Underlying the Human Glucose Facilitators Inhibition. In Vitamins and Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 128, pp. 49–92. ISBN 978-0-443-29552-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Shin, E.-J.; Kim, E.-D.; Bayaraa, T.; Frost, S.C.; Hyun, C.-K. Berberine Activates GLUT1-Mediated Glucose Uptake in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 2120–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueckler, M.; Thorens, B. The SLC2 (GLUT) Family of Membrane Transporters. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiaghaalipour, F.; Khalilpourfarshbafi, M.; Arya, A. Modulation of Glucose Transporter Protein by Dietary Flavonoids in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cok, A.; Plaisier, C.; Salie, M.J.; Oram, D.S.; Chenge, J.; Louters, L.L. Berberine Acutely Activates the Glucose Transport Activity of GLUT1. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolo, A.; Maria, Z.; Lacombe, V.A. Diabetes Causes Significant Alterations in Pulmonary Glucose Transporter Expression. Metabolites 2024, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, G.L.; Brot-Laroche, E.; Mace, O.J.; Leturque, A. Sugar Absorption in the Intestine: The Role of GLUT2. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, S.; Sun, L.; Yin, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Iwakiri, Y.; Han, J.; Duan, Y. Berberine Protects Mice against Type 2 Diabetes by Promoting PPARγ-FGF21-GLUT2-Regulated Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose/Lipid Homeostasis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cao, S.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B.-L.; Qiu, F.; Kang, N. Berberine Directly Targets AKR1B10 Protein to Modulate Lipid and Glucose Metabolism Disorders in NAFLD. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 332, 118354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala-Rabanal, M.; Ghezzi, C.; Hirayama, B.A.; Kepe, V.; Liu, J.; Barrio, J.R.; Wright, E.M. Intestinal Absorption of Glucose in Mice as Determined by Positron Emission Tomography. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 2473–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koepsell, H. Glucose Transporters in the Small Intestine in Health and Disease. Pflug. Arch.—Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1207–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Yang, E.; Li, J.; Dong, L. Berberine Decreases Intestinal GLUT2 Translocation and Reduces Intestinal Glucose Absorption in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, A.L. Regulation of GLUT4 and Insulin-Dependent Glucose Flux. ISRN Mol. Biol. 2012, 2012, 856987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, M.; Nedachi, T.; Katagiri, H.; Kanzaki, M. Functional Role of Sortilin in Myogenesis and Development of Insulin-Responsive Glucose Transport System in C2C12 Myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 10208–10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.T. Intracellular Organization of Insulin Signaling and GLUT4 Translocation. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2001, 56, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, P.; Wan, D.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, C.; Shu, G.; Mei, Z.; Yang, X. Antidiabetic Effect of Methanolic Extract from Berberis julianae Schneid. via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, J.; He, W.; Lv, J.; Zhuang, K.; Huang, H.; Quan, S. Effect of Berberine on the HPA-Axis Pathway and Skeletal Muscle GLUT4 in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Rats. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Chen, L.; Hatch, G.M. Berberine Treatment Attenuates the Palmitate-Mediated Inhibition of Glucose Uptake and Consumption through Increased 1,2,3-Triacyl-Sn-Glycerol Synthesis and Accumulation in H9c2 Cardiomyocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1861, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Nie, K.; Wu, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Jiang, X.; Tang, Y.; Su, H.; et al. Berberine Attenuates Nonalcoholic Hepatic Steatosis by Regulating Lipid Droplet-Associated Proteins: In Vivo, In Vitro and Molecular Evidence. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Luan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z. Berberine Ameliorates High-Fat-Induced Insulin Resistance in HepG2 Cells by Modulating PPARs Signaling Pathway. Curr. Comput. Aided-Drug Des. 2025, 21, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.; Geng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M. Berberine Attenuates Obesity-induced Insulin Resistance by Inhibiting miR-27a Secretion. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amssayef, A.; Eddouks, M. Alkaloids as Promising Agents for the Management of Insulin Resistance: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E.R. Type 2 Diabetes: A Multifaceted Disease. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. The Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance: Integrating Signaling Pathways and Substrate Flux. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Kleinridders, A.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Receptor Signaling in Normal and Insulin-Resistant States. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a009191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Signalling and the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nature 2001, 414, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunn, N.-O.; Kim, J.; Ryu, S.H.; Cho, Y. A Stepwise Activation Model for the Insulin Receptor. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2147–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, T.; Gao, L.; Yao, Z.; Shao, S.; Wang, X.; Proud, C.G.; Zhao, J. Hepatic Selective Insulin Resistance at the Intersection of Insulin Signaling and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteman, E.L.; Cho, H.; Birnbaum, M.J. Role of Akt/Protein Kinase B in Metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 13, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT Pathway in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. Akt Activation: A Potential Strategy to Ameliorate Insulin Resistance. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 156, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, M.; Sun, W.; Li, Q.; Xi, H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; et al. Hirsutine Ameliorates Hepatic and Cardiac Insulin Resistance in High-Fat Diet-Induced Diabetic Mice and in Vitro Models. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Su, H.; Nie, K.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Lu, F.; Dong, H. Berberine Exerts Antidepressant Effects in Vivo and in Vitro through the PI3K/AKT/CREB/BDNF Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 116012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Tao, Y.; Lu, G. Berberine Attenuates Sepsis-induced Cardiac Dysfunction by Upregulating the Akt/eNOS Pathway in Mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Jia, Y.; Pan, D.; Ma, Z. Berberine Alleviates Rotenone-Induced Cytotoxicity by Antioxidation and Activation of PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in SH-SY5Y Cells. NeuroReport 2020, 31, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Li, Z.M.; Chen, Y.T.; Dai, S.J.; Zhou, X.J.; Yang, Y.X.; Lou, J.S.; Ji, L.T.; Bao, Y.T.; Xuan, L.; et al. Berberine Improves Inflammatory Responses of Diabetes Mellitus in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats and Insulin-Resistant HepG2 Cells through the PPM1B Pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 2141508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Pan, J.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Tong, Q.; Fang, J.; Wan, L.; Chen, J. Xiaokeyinshui Extract Combination, a Berberine-Containing Agent, Exerts Anti-Diabetic and Renal Protective Effects on Rats in Multi-Target Mechanisms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Lin, C.; Xie, F.; Jin, M.; Lin, F. Berberine Ameliorates Insulin Resistance by Inhibiting IKK/NF-κB, JNK, and IRS-1/AKT Signaling Pathway in Liver of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Rats. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2022, 20, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; Jiang, R.; Kou, X.; Sheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y. Berberine Improves TNF-α-Induced Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Targeting MEKK1/MEK Pathway. Inflammation 2022, 45, 2016–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, M.R.; Mohammadipanah, S.; Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M. The Pharmacological Effects of Berberine and Its Therapeutic Potential in Different Diseases: Role of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT Signaling Pathway. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J. Berberine Decreases Insulin Resistance in a PCOS Rats by Improving GLUT4: Dual Regulation of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK Pathways. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 110, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, B.; Hang, W.; Wu, N.; Xia, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. Berberine Alleviates Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Axonopathy-Associated with Diabetic Encephalopathy via Restoring PI3K/Akt/GSK3β Pathway. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 65, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, M.; Yan, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Z.; Cui, A.; Ma, F.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Q.; et al. Berberine Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Enhances Energy Expenditure in Mice by Inducing Autophagy and Fibroblast Growth Factor 21. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, K.H.; Yoon, M.J.; Cho, H.J.; Shen, Y.; Ye, J.-M.; Lee, C.H.; Oh, W.K.; Kim, C.T.; et al. Berberine, a Natural Plant Product, Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase with Beneficial Metabolic Effects in Diabetic and Insulin-Resistant States. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Wang, W.; Murono, N.; Iwasa, K.; Inoue, M. Potential Role of Akt in the Regulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 by Berberine. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 78, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Cheong, M.S.; Chen, X.; Farag, M.A.; Cheang, W.S.; Xiao, J. Baicalin Ameliorates Insulin Resistance and Regulates Hepatic Glucose Metabolism via Activating Insulin Signaling Pathway in Obese Pre-Diabetic Mice. Phytomedicine 2024, 124, 155296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Khosravi, K.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Garzoli, S. A Mechanistic Review on How Berberine Use Combats Diabetes and Related Complications: Molecular, Cellular, and Metabolic Effects. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.; Singh, A.K.; Haratipour, P.; Sah, A.N.; Pandey, A.K.; Naseri, R.; Juyal, V.; Farzaei, M.H. Targeting AMPK Signaling Pathway by Natural Products for Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 17212–17231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Zou, X.; Lu, F.; Yi, P. Berberine Inhibits Gluconeogenesis in Skeletal Muscles and Adipose Tissues in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats via LKB1-AMPK-TORC2 Signaling Pathway. Curr. Med Sci. 2020, 40, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.-J. Berberine Inhibits Hepatic Gluconeogenesis via the LKB1-AMPK-TORC2 Signaling Pathway in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Meng, Z.; Wei, S.; Du, H.; Chen, L.; Hatch, G.M. Berberine Improves Insulin Resistance in Cardiomyocytes via Activation of 5′-Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase. Metabolism 2013, 62, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araj-Khodaei, M.; Ayati, M.H.; Azizi Zeinalhajlou, A.; Novinbahador, T.; Yousefi, M.; Shiri, M.; Mahmoodpoor, A.; Shamekh, A.; Namazi, N.; Sanaie, S. Berberine-Induced Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and Its Mechanism for Controlling Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Comprehensive Pathway Review. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 130, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, P.; Chepurny, O.G.; Holz, G.G. Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis by GLP-1. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 121, pp. 23–65. ISBN 978-0-12-800101-1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Bai, M.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; et al. Study on the Mechanism of Modified Gegen Qinlian Decoction in Regulating the Intestinal Flora-Bile Acid-TGR5 Axis for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Based on Macro Genome Sequencing and Targeted Metabonomics Integration. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; He, W.; Luo, Z.; Wang, K.; Tan, X. Achyranthes Bidentata Polysaccharide Ameliorates Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids-Induced Activation of the GLP-1/GLP-1R/cAMP/PKA/CREB/INS Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Cui, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, D.; Li, F.; Lin, X.; Gu, L.; Yang, K.; Yang, J.; et al. Glucagon Acting at the GLP-1 Receptor Contributes to β-Cell Regeneration Induced by Glucagon Receptor Antagonism in Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2023, 72, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Feng, J.; Wei, T.; Zhang, L.; Lang, S.; Yang, K.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Sterr, M.; Lickert, H.; et al. Pancreatic Alpha Cell Glucagon–Liver FGF21 Axis Regulates Beta Cell Regeneration in a Mouse Model of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, J.; Manaka, K.; Horikoshi, H.; Taguchi, M.; Harada, K.; Tsuboi, T.; Nangaku, M.; Iiri, T.; Makita, N. Insights into GLP-1 and Insulin Secretion Mechanisms in Pasireotide-Induced Hyperglycemia Highlight Effectiveness of Gs-Targeting Diabetes Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Liang, J.; Gu, F.; Du, D.; Chen, F. Berberine Activates Bitter Taste Responses of Enteroendocrine STC-1 Cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 447, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; Jia, W.; Le, J.; Ye, J. Restoration of GLP-1 Secretion by Berberine Is Associated with Protection of Colon Enterocytes from Mitochondrial Overheating in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.-L.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Ji, W.-Y.; Zhao, L.-L.; Yang, F.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X. Berberine Metabolites Stimulate GLP-1 Secretion by Alleviating Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony, R.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Overview of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetes. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuryłowicz, A.; Koźniewski, K. Anti-Inflammatory Strategies Targeting Metaflammation in Type 2 Diabetes. Molecules 2020, 25, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 Diabetes as an Inflammatory Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbudi, A.; Rahmadika, N.; Tjahjadi, A.I.; Ruslami, R. Type 2 Diabetes and Its Impact on the Immune System. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020, 16, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Singh, B.P.; Sandhu, N.; Singh, N.; Kaur, R.; Rokana, N.; Singh, K.S.; Chaudhary, V.; Panwar, H. Probiotic Mediated NF-κB Regulation for Prospective Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2301–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandona, P. Inflammation: The Link between Insulin Resistance, Obesity and Diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, H. The Combination of Berberine and Isoliquiritigenin Synergistically Improved Adipose Inflammation and Obesity-induced Insulin Resistance. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 3839–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zand, H. Signaling Pathways Linking Inflammation to Insulin Resistance. Metab. Syndr. 2016, 11, S307–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson, S.E. Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Jing, R.; Shi, M.; Yang, Y.; Feng, M.; Deng, L.; Luo, L. BBR Affects Macrophage Polarization via Inhibition of NF-κB Pathway to Protect against T2DM-associated Periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2024, 59, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokajuk, A.; Krzyżanowska-Grycel, E.; Tokajuk, A.; Grycel, S.; Sadowska, A.; Car, H. Antidiabetic Drugs and Risk of Cancer. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 67, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olefsky, J.M.; Glass, C.K. Macrophages, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojta, I.; Chacińska, M.; Błachnio-Zabielska, A. Obesity, Bioactive Lipids, and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.; Ghotbabadi, Z.R.; Kazemi, K.S.; Metghalchi, Y.; Tavakoli, R.; Rahimabadi, R.Z.; Ghaheri, M. The Effect of Berberine Supplementation on Glycemic Control and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Metabolic Disorders: An Umbrella Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Ther. 2024, 46, e64–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gu, L.; Si, Y.; Yin, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, M. Macrovascular Protecting Effects of Berberine through Anti-Inflammation and Intervention of BKCa in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Rats. Endocrine Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2021, 21, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Epigenetic Regulation in the Tumor Microenvironment: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.; Saadat, A. Neurodegeneration and Epigenetics: A Review. Neurología 2023, 38, e62–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Chiou, J.; Zeng, C.; Miller, M.; Matta, I.; Han, J.Y.; Kadakia, N.; Okino, M.-L.; Beebe, E.; Mallick, M.; et al. Integrating Genetics with Single-Cell Multiomic Measurements across Disease States Identifies Mechanisms of Beta Cell Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefond, A.; Florez, J.C.; Loos, R.J.F.; Froguel, P. Dissection of Type 2 Diabetes: A Genetic Perspective. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Hatzikotoulas, K.; Southam, L.; Taylor, H.J.; Yin, X.; Lorenz, K.M.; Mandla, R.; Huerta-Chagoya, A.; Melloni, G.E.M.; Kanoni, S.; et al. Genetic Drivers of Heterogeneity in Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology. Nature 2024, 627, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Rönn, T. Epigenetics in Human Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Hu, H.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Z.; Meng, F.; Liang, S. Berberine Acts as a Putative Epigenetic Modulator by Affecting the Histone Code. Toxicol. In Vitro 2016, 36, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, R.; Karnib, N.; Assaad, R.A.; Bilen, Y.; Emmanuel, N.; Ghanem, A.; Younes, J.; Zibara, V.; Stephan, J.S.; Sleiman, S.F. Epigenetic Changes in Diabetes. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 625, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, P.; Bacos, K.; Ofori, J.K.; Esguerra, J.L.S.; Eliasson, L.; Rönn, T.; Ling, C. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing of Human Pancreatic Islets Reveals Novel Differentially Methylated Regions in Type 2 Diabetes Pathogenesis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhu, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, C.; Su, L.; Chen, K.; Li, Y. Berberine Inhibits KLF4 Promoter Methylation and Ferroptosis to Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 1728–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, W.; Lv, S.; Qu, H.; He, Y. Berberine Improves Insulin Resistance in Adipocyte Models by Regulating the Methylation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-3α. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20192059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Guan, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Lv, X.; Guan, F. Berberine Mitigates Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Enhancing Mitochondrial Architecture via the SIRT1/Opa1 Signalling Pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Pan, Y.; Xu, L.; Tang, D.; Dorfman, R.G.; Zhou, Q.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, S.; et al. Berberine Promotes Glucose Uptake and Inhibits Gluconeogenesis by Inhibiting Deacetylase SIRT3. Endocrine 2018, 62, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gao, B.; Liang, S.; Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Ye, L.; Yang, Q.; Shang, W. Adipose Tissue SIRT1 Regulates Insulin Sensitizing and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberine. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 591227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M. The αβδ of Ion Channels in Human Islet Cells. Islets 2009, 1, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorsman, P.; Ashcroft, F.M. Pancreatic β-Cell Electrical Activity and Insulin Secretion: Of Mice and Men. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 117–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneto, H.; Matsuoka, T.; Katakami, N.; Kawamori, D.; Miyatsuka, T.; Yoshiuchi, K.; Yasuda, T.; Sakamoto, K.; Yamasaki, Y.; Matsuhisa, M. Oxidative Stress and the JNK Pathway Are Involved in the Development of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Mol. Med. 2007, 7, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Mechanistic Insight into Oxidative Stress-Triggered Signaling Pathways and Type 2 Diabetes. Molecules 2022, 27, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Mechanism of Generation of Oxidative Stress and Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: How Are They Interlinked? J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 3577–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-D.; Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Yu, C.-J.; Li, J.-Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Yang, D.; Guo, C.-L.; Du, X.; Zhang, W.-J.; et al. Effect of Berberine on Hyperglycaemia and Gut Microbiota Composition in Type 2 Diabetic Goto-Kakizaki Rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Han, H.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Berberine Potentiates Insulin Secretion and Prevents β-Cell Dysfunction Through the miR-204/SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 720866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; She, J.; Ma, L.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Zhai, J. Berberine Protects against Palmitate Induced Beta Cell Injury via Promoting Mitophagy. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chueh, W.-H.; Lin, J.-Y. Berberine, an Isoquinoline Alkaloid, Inhibits Streptozotocin-Induced Apoptosis in Mouse Pancreatic Islets through down-Regulating Bax/Bcl-2 Gene Expression Ratio. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfakhrabadi, F.; Niknejad, M.R.; Kalantari, H.; Dehghani, M.A.; Shakiba Maram, N.; Ahangarpour, A. Evaluation of the Protective Effects of Berberine and Berberine Nanoparticle on Insulin Secretion and Oxidative Stress Induced by Carbon Nanotubes in Isolated Mice Islets of Langerhans: An in Vitro Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 21781–21796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Du, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Teng, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Feng, L.; Cui, X.; et al. Amorphous Solid Dispersion of Berberine Mitigates Apoptosis via iPLA2 β/Cardiolipin/Opa1 Pathway in Db/Db Mice and in Palmitate-Treated MIN6 β-Cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-Y.; Cui, H.-M.; Wang, J.-L.; Liu, H.; Dang, M.-M.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Yang, F.; Kou, J.-T.; Tong, X.-L. Protective Role of Berberine and Coptischinensis Extract on T2MD Rats and Associated Islet Rin-5f Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 6981–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.-M.; Lu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, X.; Li, Q.; Shi, T.-T.; Matsunaga, K.; Chen, C.; Huang, H.; et al. Berberine Is an Insulin Secretagogue Targeting the KCNH6 Potassium Channel. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Zahoor, I.; Albarrati, A.; Albratty, M.; Meraya, A.M.; Najmi, A.; Bungau, S. Expatiating the Pharmacological and Nanotechnological Aspects of the Alkaloidal Drug Berberine: Current and Future Trends. Molecules 2022, 27, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Carvalho, C.; Santos, M.; Seica, R.; Oliveira, C.; Moreira, P. Mechanisms of Action of Metformin in Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Complications: An Overview. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, C.; Ying, Y.; Luo, L.; Huang, D.; Luo, Z. Metformin and Berberine, Two Versatile Drugs in Treatment of Common Metabolic Diseases. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 10135–10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Li, D.; Yuan, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ming, X.; Shaw, P.C.; Zhang, C.; Kong, A.P.S.; Zuo, Z. Effects of Combination Treatment with Metformin and Berberine on Hypoglycemic Activity and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Db/Db Mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 101, 154099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.; Santangelo, R. Panax Ginseng and Panax Quinquefolius: From Pharmacology to Toxicology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Xie, W.; He, S.; Sun, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, G.; Sun, X. Ginsenoside Rb1 as an Anti-Diabetic Agent and Its Underlying Mechanism Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Chen, Y. Synergetic Protective Effect of Berberine and Ginsenoside Rb1 against Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha−induced Inflammation in Adipocytes. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 11784–11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Yang, H.-Z.; Su, H.; Song, J.; Bai, Y.; Deng, L.; Feng, C.-P.; Guo, H.-X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; et al. Berberine and Ginsenoside Rb1 Ameliorate Depression-Like Behavior in Diabetic Rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, A.; Zhang, P.; Peng, X.; Lu, X.; Fan, X. Ginsenoside Rb1 and Berberine Synergistically Protect against Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via GDF15/HAMP Pathway throughout the Liver Lobules: Insights from Spatial Transcriptomics Analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 215, 107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ren, H.; Zhong, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Ma, J.; Gu, X.; Xue, Y.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; et al. Combined Berberine and Probiotic Treatment as an Effective Regimen for Improving Postprandial Hyperlipidemia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Double Blinded Placebo Controlled Randomized Study. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2003176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.K.; Omaye, S.T. Metabolic Diseases and Pro- and Prebiotics: Mechanistic Insights. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, C.; Lei, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Huan, Y.; Sun, S.; Shen, Z. Stachyose Improves the Effects of Berberine on Glucose Metabolism by Regulating Intestinal Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Spontaneous Type 2 Diabetic KKAy Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 578943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Liu, M.; Li, R.; Sun, S.; Liu, S.; Huan, Y.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Q.; et al. Berberine Combined with Stachyose Induces Better Glycometabolism than Berberine Alone through Modulating Gut Microbiota and Fecal Metabolomics in Diabetic Mice. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cao, H.; Huan, Y.; Ji, W.; Liu, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, Q.; Lei, L.; Liu, M.; Gao, X.; et al. Berberine Combined with Stachyose Improves Glycometabolism and Gut Microbiota through Regulating Colonic microRNA and Gene Expression in Diabetic Rats. Life Sci. 2021, 284, 119928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Lin, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, P.; Chen, M.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Enhanced Anti-Diabetic Effect of Berberine Combined with Timosaponin B2 in Goto-Kakizaki Rats, Associated With Increased Variety and Exposure of Effective Substances Through Intestinal Absorption. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Leng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Xie, H.; Gao, H.; Xie, C. The Potential of Astragalus Polysaccharide for Treating Diabetes and Its Action Mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1339406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.-J.; Lin, M.; Zhang, X.; Qin, L.-P. Combined Use of Astragalus Polysaccharide and Berberine Attenuates Insulin Resistance in IR-HepG2 Cells via Regulation of the Gluconeogenesis Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Su, F.; Wang, G.; Peng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Hou, K.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Glucose-Lowering Effect of Berberine on Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1015045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Mohanty, S. Efficacy and Safety of HIMABERB® Berberine on Glycemic Control in Patients with Prediabetes: Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, and Randomized Pilot Trial. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, D.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Zhu, N.; Huo, L.; Wang, M.; Hong, J.; Wu, P.; et al. Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes and Dyslipidemia with the Natural Plant Alkaloid Berberine. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, R.; Ni, J. Effects of Berberine on Blood Glucose in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Literature Review and a Meta-Analysis. Endocr. J. 2019, 66, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Sajjadi-Jazi, S.M.; Gerami, H.; Khorasanian, A.S.; Moalemzadeh, B.; Karimi, S.; Afrakoti, N.M.; Mofid, V.; Mohajeri-Tehrani, M.R.; Hekmatdoost, A. The Efficacy and Safety of Berberine in Combination with Cinnamon Supplementation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, S.; Pishdad, G.R.; Zakerkish, M.; Namjoyan, F.; Ahmadi Angali, K.; Borazjani, F. The Effect of Berberine and Fenugreek Seed Co-Supplementation on Inflammatory Factor, Lipid and Glycemic Profile in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Double-Blind Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore, G.; Ragazzi, E.; Antonello, G.; Cosma, C.; Lapolla, A. Effect of a New Formulation of Nutraceuticals as an Add-On to Metformin Monotherapy for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Suboptimal Glycemic Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.-D.; Shi, G.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, C.; Zhu, C. A Review on the Potential of Resveratrol in Prevention and Therapy of Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popykhova, E.B.; Ivanov, A.N.; Stepanova, T.V.; Lagutina, D.D.; Savkina, A.A. Diabetic Nephropathy—Possibilities of Early Laboratory Diagnostics and Course Prediction (Review of Literature). Klin. Lab. Diagn. 2021, 66, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, B.; Alpers, C.E.; Fogo, A.B. Pathology of Human Diabetic Nephropathy. In Contributions to Nephrology; Lai, K.N., Tang, S.C.W., Eds.; S. Karger AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 170, pp. 36–47. ISBN 978-3-8055-9742-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, E.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, J.; Li, W.; Wei, P.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Protective Effect of Berberine in Diabetic Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Revealing the Mechanism of Action. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 185, 106481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L. Berberine Protects Diabetic Nephropathy by Suppressing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Involving the Inactivation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, D.L.; Green, N.H.; Danesh, F.R. The Hallmarks of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, J.; Su, H.; Yuan, F.; Fang, K.; Yuan, X.; Yu, X.; Dong, H.; et al. Berberine Protects against Diabetic Kidney Disease via Promoting PGC-1α-regulated Mitochondrial Energy Homeostasis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3646–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, J.; Huang, W.; Su, H.; Yuan, F.; Fang, K.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Zou, X.; et al. Berberine Protects Glomerular Podocytes via Inhibiting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission and Dysfunction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1698–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.; Mitchell, P.; Wong, T.Y. Diabetic Retinopathy. Lancet 2010, 376, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z. Mechanistic pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 816400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Feng, X.; Chai, L.; Cao, S.; Qiu, F. The metabolism of berberine and its contribution to the pharmacological effects. Drug Metab. Rev. 2017, 49, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhao, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, W. Berberine Alleviates Diabetic Retinopathy by Regulating the Th17/Treg Ratio. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 267, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Yu, P.; Luo, L.; Sun, J.; Tao, H.; Wang, X.; Meng, X. Berberis Dictyophylla F. Inhibits Angiogenesis and Apoptosis of Diabetic Retinopathy via Suppressing HIF-1α/VEGF/DLL-4/Notch-1 Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 296, 115453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Li, M.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Berberine Protects against Diabetic Retinopathy by Inhibiting Cell Apoptosis via Deactivation of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 4227–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Cicero, A.F. Berberine on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: An Analysis from Preclinical Evidences to Clinical Trials. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between Insulin Resistance and the Development of Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillmann, W.H. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: What Is It and Can It Be Fixed? Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jin, T.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, C.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.; Ju, J.; Cheng, T.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Berberine Partially Ameliorates Cardiolipotoxicity in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy by Modulating SIRT3-mediated Lipophagy to Remodel Lipid Droplets Homeostasis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 5038–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cheng, C.-F.; Li, Z.-F.; Huang, X.-J.; Cai, S.-Q.; Ye, S.-Y.; Zhao, L.-J.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, D.-F.; Liu, H.-L.; et al. Berberine Blocks Inflammasome Activation and Alleviates Diabetic Cardiomyopathy via the miR-18a-3p/Gsdmd Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 51, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Q.; Cheng, T.; Li, M.; Ju, J.; et al. Berberine Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Regulating mTOR/mtROS Axis to Alleviate Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 964, 176253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.L.; Callaghan, B.C.; Pop-Busui, R.; Zochodne, D.W.; Wright, D.E.; Bennett, D.L.; Bril, V.; Russell, J.W.; Viswanathan, V. Diabetic Neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, P.; Ye, T.; Gao, H.; Ye, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Berberine Ameliorates Rats Model of Combined Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via the Suppression of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, J.; Noordin, S. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Contemporary Assessment and Management. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2023, 73, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadian, H.; Zamiri, S.; Ehterami, A.; Farzamfar, S.; Vaez, A.; Khastar, H.; Alam, M.; Ai, A.; Derakhshankhah, H.; Allahyari, Z.; et al. Electrospun Cellulose Acetate/Gelatin Nanofibrous Wound Dressing Containing Berberine for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Healing: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Xiang, C.; Cao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J. Berberine Accelerated Wound Healing by Restoring TrxR1/JNK in Diabetes. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Rao, X.; Shen, C.; Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Fang, C.; Zhou, F.; Ding, Z.; et al. Microenvironment-Responsive, Multimodulated Herbal Polysaccharide Hydrogel for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Healing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baska, A.; Leis, K.; Gałązka, P. Berberine in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Endocrine Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2021, 21, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. (Eds.) Anti-Inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 928, ISBN 978-3-319-41332-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Qiang, W.; Chang, L.; Xiao, K.; Zhou, R.; Qiu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Li, X.; Chi, C.; Liu, W.; et al. Integrative Whole-Genome Methylation and Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Epigenetic Modulation of Glucose Metabolism by Dietary Berberine in Blunt Snout Bream (Megalobrama Amblycephala). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2025, 278, 111098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ekavali; Chopra, K.; Mukherjee, M.; Pottabathini, R.; Dhull, D.K. Current Knowledge and Pharmacological Profile of Berberine: An Update. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 761, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-S.; Zheng, Y.-R.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Long, X.-Y. Research Progress on Berberine with a Special Focus on Its Oral Bioavailability. Fitoterapia 2016, 109, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnier, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kuo, Y.; Du, M.; Roh, K.; Gahler, R.; Wood, S.; Chang, C. Characterization and Pharmacokinetic Assessment of a New Berberine Formulation with Enhanced Absorption In Vitro and in Human Volunteers. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.J.; Hafeez, A.; Siddiqui, M.A. Nanocarrier Based Delivery of Berberine: A Critical Review on Pharmaceuticaland Preclinical Characteristics of the Bioactive. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, F.A.; Saleh, S.R.; El-Rahman, S.S.A.; Newairy, A.-S.A.; El-Demellawy, M.A.; Ghareeb, D.A. Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Berberine-Entrapped Albumin Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, M.; Jiang, S.; Shang, P.; Dong, X.; Li, L. Research Progress on Pharmacological Effects and Bioavailability of Berberine. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 8485–8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-L.; Tsai, T.-H. HEPATOBILIARY EXCRETION OF BERBERINE. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, F.; Yan, Z.; Zheng, W.; Fan, J.; Sun, G. Meta-Analysis of the Effect and Safety of Berberine in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Hyperlipemia and Hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 161, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imenshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Berberis Vulgaris and Berberine: An Update Review. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1745–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, D.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y. Berberine: A Rising Star in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Novel Insights into Its Anti-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121890

Liu D, Zhao L, Wang Y, Wang L, Wu D, Liu Y. Berberine: A Rising Star in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Novel Insights into Its Anti-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121890

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Da, Liting Zhao, Ying Wang, Lei Wang, Donglu Wu, and Yangyang Liu. 2025. "Berberine: A Rising Star in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Novel Insights into Its Anti-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Mechanisms" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121890

APA StyleLiu, D., Zhao, L., Wang, Y., Wang, L., Wu, D., & Liu, Y. (2025). Berberine: A Rising Star in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes—Novel Insights into Its Anti-Inflammatory, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121890