The Impact of Maternal BMI on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Misoprostol for Labor Induction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Study Population

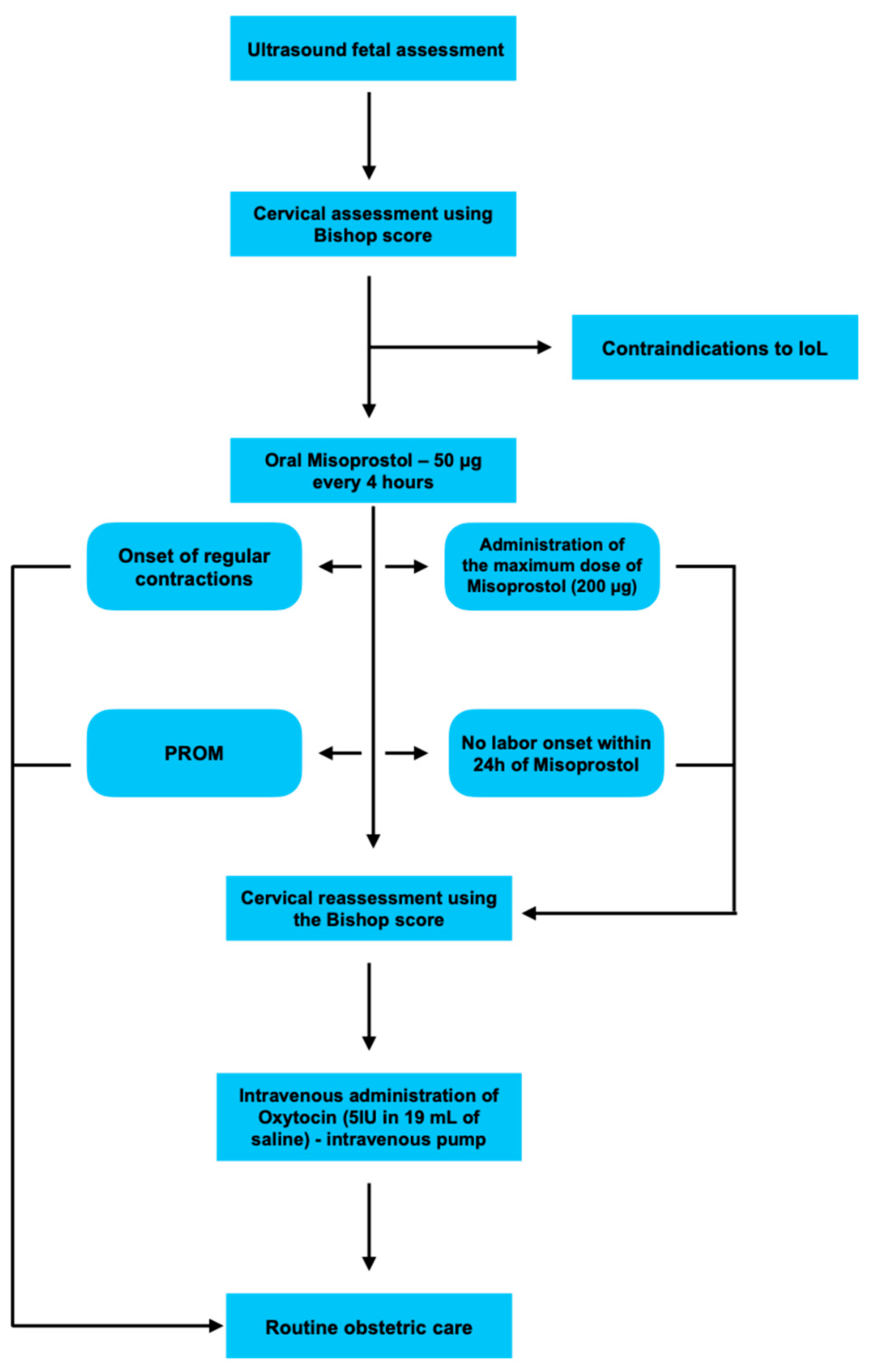

4.3. Interventions

- Onset of regular uterine contractions;

- PROM;

- Administration of the maximum total dose (200 μg).

- Class I (BMI 30.0–34.9);

- Class II (BMI 35.0–39.9);

- Class III (morbid obesity, BMI ≥ 40).

4.4. Outcomes

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langley-Evans, S.C.; Pearce, J.; Ellis, S. Overweight, Obesity and Excessive Weight Gain in Pregnancy as Risk Factors for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Narrative Review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- AlAnnaz, W.A.A.; Gouda, A.D.K.; Abou El-Soud, F.A.; Alanazi, M.R. Obesity Prevalence and Its Impact on Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes among Pregnant Women: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study Design. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1236–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orós, M.; Lorenzo, M.; Serna, M.C.; Siscart, J.; Perejón, D.; Salinas-Roca, B. Obesity in Pregnancy as a Risk Factor in Maternal and Child Health—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Metabolites 2024, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, P.M.; Shankar, K. Obesity and Pregnancy: Mechanisms of Short Term and Long Term Adverse Consequences for Mother and Child. BMJ 2017, 356, j1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of Labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 386–397. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ramos, L.; Levine, L.D.; Sciscione, A.C.; Mozurkewich, E.L.; Ramsey, P.S.; Adair, C.D.; Kaunitz, A.M.; McKinney, J.A. Methods for the Induction of Labor: Efficacy and Safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S669–S695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Bapoo, S.; Shukla, M.; Abbasi, N.; Horn, D.; D’Souza, R. Induction of Labour in Low-Risk Pregnancies before 40 Weeks of Gestation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 79, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.C.; Delaney, T.; Anthony Armson, B.; Fanning, C. Oral Misoprostol, Low Dose Vaginal Misoprostol, and Vaginal Dinoprostone for Labor Induction: Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0304233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.C.; Sanchez-Ramos, L.; Adair, C.D. Labor Induction with Intravaginal Misoprostol Compared with the Dinoprostone Vaginal Insert: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 624.e1–624.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatsis, V.; Frey, N. Misoprostol for Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labour: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness and Guidelines [Internet]; CADTH: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, D.A.; Rahall, A.; Jones, M.M.; Goodwin, T.M.; Paul, R.H. Misoprostol: An Effective Agent for Cervical Ripening and Labor Induction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 172, 1811–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Aflaifel, N.; Weeks, A. Oral Misoprostol for Induction of Labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD001338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, V.L.; Rajamanya, A.V.; Yelikar, K.A. Oral Misoprostol Solution for Induction of Labour. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2017, 67, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduloju, O.P.; Ipinnimo, O.M.; Aduloju, T. Oral Misoprostol for Induction of Labor at Term: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Hourly Titrated and 2 Hourly Static Oral Misoprostol Solution. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 34, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlhäll, S.; Källén, K.; Blomberg, M. Maternal Body Mass Index and Duration of Labor. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Troendle, J.F. Maternal Prepregnancy Overweight and Obesity and the Pattern of Labor Progression in Term Nulliparous Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 104, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomba-Opoń, D.; Drews, K.; Huras, H.; Laudański, P.; Paszkowski, T.; Wielgoś, M. Polish Gynecological Society Recommendations for Labor Induction. Ginekol. Pol. 2017, 88, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K.; Kirby, M.A.; Hughes, F.; Yellon, S.M. Reassessing the Bishop Score in Clinical Practice for Induction of Labor Leading to Vaginal Delivery and for Evaluation of Cervix Ripening. Placenta Reprod. Med. 2023, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Tandel, M.D.; Kwan, L.; Francoeur, A.A.; Duong, H.L.; Negi, M. Favorable Simplified Bishop Score after Cervical Ripening Associated with Decreased Cesarean Birth Rate. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2022, 4, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, A.; Fasoulakis, Z.; Domali, E.; Daskalakis, G.; Antsaklis, P. Role of the Bishop Score in Predicting Successful Induction of Vaginal Delivery: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Cureus 2025, 17, e87467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolkman, D.G.E.; Verhoeven, C.J.M.; Brinkhorst, S.J.; Van Der Post, J.A.M.; Pajkrt, E.; Opmeer, B.C.; Mol, B.J. The Bishop Score as a Predictor of Labor Induction Success: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations on Induction of Labour, at or Beyond Term; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, R.S.; Kumar, N.; Williams, M.J.; Cuthbert, A.; Aflaifel, N.; Haas, D.M.; Weeks, A.D. Low-Dose Oral Misoprostol for Induction of Labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD014484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Eikelder, M.L.G.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Jozwiak, M.; De Leeuw, J.W.; De Graaf, I.M.; Van Pampus, M.G.; Holswilder, M.; Oudijk, M.A.; Van Baaren, G.J.; Pernet, P.J.M.; et al. Induction of Labour at Term with Oral Misoprostol versus a Foley Catheter (PROBAAT-II): A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Bashour, G.; Eldokmery, E.; Alkhawajah, A.; Alsalhi, K.; Badr, Y.; Emad, A.; Labieb, F. The Efficacy and Safety of Oral and Vaginal Misoprostol versus Dinoprostone on Women Experiencing Labor: A Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis of 53 Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine 2024, 103, e39861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenuberi, H.; Mathews, J.; George, A.; Benjamin, S.; Rathore, S.; Tirkey, R.; Tharyan, P. The Efficacy and Safety of 25 Μg or 50 Μg Oral Misoprostol versus 25 Μg Vaginal Misoprostol given at 4- or 6-Hourly Intervals for Induction of Labour in Women at or beyond Term with Live Singleton Pregnancies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 164, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angolile, C.M.; Max, B.L.; Mushemba, J.; Mashauri, H.L. Global Increased Cesarean Section Rates and Public Health Implications: A Call to Action. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nace, M.C.; Delotte, J.; Gauci, P.A. Comparative Study of Second-Line Labor Induction Methods in Patients with Unfavorable Cervix after First-Line Low-Dose Oral Misoprostol. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 167, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesny, W.; Kjøllesdal, M.; Karlsson, B.; Nielsen, S. Bishop Score and the Outcome of Labor Induction with Misoprostol. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2006, 85, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, R.; Pierce, S.; Myers, D. The Role of Prostaglandins E1 and E2, Dinoprostone, and Misoprostol in Cervical Ripening and the Induction of Labor: A Mechanistic Approach. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallén, N.; Amini, M.; Wide-Swensson, D.; Herbst, A. Outpatient vs Inpatient Induction of Labor with Oral Misoprostol: A Retrospective Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, E.H.; McGuire, J.; Lo, J.; McIntire, D.D.; Spong, C.Y.; Nelson, D.B. Vaginal Compared with Oral Misoprostol Induction at Term: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 143, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, W.C.; Charlab, R.; Burckart, G.J.; Stewart, C.F. Effect of Obesity on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Anticancer Agents. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, S85–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, R.B.; Brogaard, L.; Hvidman, L. Women’s Body Mass Index and Oral Administration of Misoprostol for Induction of Labor—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 15, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, M.; Bettonte, S.; Stader, F.; Battegay, M.; Marzolini, C. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling to Identify Physiological and Drug Parameters Driving Pharmacokinetics in Obese Individuals. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 62, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, D.; Kumar, V. The Role of “Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model (PBPK)” New Approach Methodology (NAM) in Pharmaceuticals and Environmental Chemical Risk Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, G.J.; Bernitz, S.; Bonet, M.; Bucagu, M.; Dao, B.; Downe, S.; Galadanci, H.; Homer, C.S.E.; Hundley, V.; Lavender, T.; et al. WHO Next-Generation Partograph: Revolutionary Steps towards Individualised Labour Care. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 1658–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.B.; McIntire, D.D.; Leveno, K.J. Relationship of the Length of the First Stage of Labor to the Length of the Second Stage. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, A.; Jafari-Azar, Z.; Anabi, M.; Davari Dolatabadi, M. Effect of Misoprostol versus Oxytocin on Delivery Outcomes after Labour Induction in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 292, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druenne, J.; Semay, T.; Giraud, A.; Chauleur, C.; Raia-Barjat, T. Pain and Satisfaction in Women Induced by Vaginal Dinoprostone, Double Balloon Catheter and Oral Misoprostol. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.I.; Li, W.; Goni, S.; Flanagan, M.; Weeks, A.; Alfirevic, Z.; Bracken, H.; Mundle, S.; Goonewardene, M.; ten Eikelder, M.; et al. Foley Catheter vs Oral Misoprostol for Induction of Labor: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Wahaibi, S.; Czuzoj-Shulman, N.; Abenhaim, H. Induction of Labor and Risk of Third- and Fourth-Degree Perineal Tears. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2020, 42, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.H.; Franzén, K.; Hiyoshi, A.; Tegerstedt, G.; Dahlgren, H.; Nilsson, K. Risk Factors for Perineal and Vaginal Tears in Primiparous Women—The Prospective POPRACT-Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.; Bolnga, J.W.; Verave, O.; Aipit, J.; Rero, A.; Laman, M. Safety and Effectiveness of Oral Misoprostol for Induction of Labour in a Resource-Limited Setting: A Dose Escalation Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, A.; Harris-Haman, P.A. Review of the Reliability and Validity of the Apgar Score. Adv. Neonatal. Care 2022, 22, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Group (n = 291) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 30.4 | |

| Range | 18.0–46.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 31.0 (6.0) | |

| 95%CI | [29.9; 30.9] | |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| Mean | 81.2 | |

| Range | 59.4–140.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 80.0 (17.0) | |

| 95%CI | [79.6; 82.7] | |

| Age of gestation (weeks) | ||

| 37 | 11 (3.8%) | |

| 38 | 32 (11.0%) | |

| 39 | 77 (26.5%) | |

| 40 | 63 (21.6%) | |

| 41 | 81 (27.8%) | |

| 42 | 27 (9.3%) | |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 209 (71.8%) | |

| Multiparous | 82 (28.2%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Normal weight | 18.5–25 | 49 (16.8%) |

| Overweight | 25–30 | 125 (43.0%) |

| Obesity class I | 30–34.9 | 96 (33.0%) |

| Obesity class II | 35–39.9 | 16 (5.5%) |

| Obesity class III | >40 | 5 (1.7%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Mean | 29.3 | |

| Range | 20.5–51.4 | |

| median (IRQ) | 29.0 (5.8) | |

| 95%CI | [28.8; 29.8] | |

| Indications for IoL | ||

| Post-term pregnancy | 102 (35.1%) | |

| Large for gestational age (LGA) | 62 (21.3%) | |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) | 37 (12.2%) | |

| Fetal growth restriction (FGR) | 24 (8.2%) | |

| Oligohydramnios | 22 (7.7%) | |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus type 2 (GDM G2) | 18 (6.3%) | |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus type 1 (GDM G1) | 15 (5.4%) | |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) | 4 (1.4%) | |

| Polyhydramnios | 4 (1.4%) | |

| Maternal Age > 40 Years | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Small for gestational age (SGA) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Group (n = 291) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial BS | 0.704 1 | |

| mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.1) | |

| range | 0.0–5.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 2.0 (1.0) | |

| 95%CI | [2.2; 2.5] | |

| BS after oral Misoprostol | <0.0001 1 | |

| mean (SD) | 6.2 (2.3) | |

| range | 1.0–12.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 6.0 (3.0) | |

| 95%CI | [6.0; 6.5] |

| Group (n = 291) | |

|---|---|

| Overall | |

| mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.1) |

| range | 1.0–4.0 |

| median (IRQ) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| 95%CI | [2.9; 3.2] |

| Misoprostol doses | |

| 1 | 9 (3.1%) |

| 2 | 13 (4.5%) |

| 3 | 116 (39.8%) |

| 4 | 153 (52.6%) |

| Reason for discontinuation | |

| Uterine contractions | 126 (43.4%) |

| PROM | 12 (4.1%) |

| Type of Delivery | Group (n = 291) |

|---|---|

| Vaginal delivery (VD) | 225 (77.3%) |

| Cesarean section (CS) | 66 (22.7%) |

| Delivery (Vaginal and Cesarean) | Group (n = 291) |

|---|---|

| 24 h | |

| 181 (62.2%) | |

| >24–48 h | |

| 100 (34.4%) | |

| >48 h | |

| 10 (3.4%) |

| VD (n = 225) | CS (n = 66) | Total (n = 291) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | |||

| 145 (64.4%) | 36 (54.5%) | 181 | |

| >24–48 h | |||

| 74 (32.9%) | 26 (39.4%) | 100 | |

| >48 h | |||

| 6 (2.7%) | 4 (6.1%) | 10 |

| Group (n = 12) | |

|---|---|

| 24 h | n = 11 |

| Obstetrical forceps (F) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Vacuum extractor (VE) | 11 (100.0%) |

| >24–48 h | n = 1 |

| Obstetrical forceps (F) | 1 (100.0%) |

| Vacuum extractor (VE) | 0 (0.0%) |

| >48 h | n = 0 |

| Obstetrical forceps (F) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Vacuum extractor (VE) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Group (n = 66) | |

|---|---|

| 24 h | n = 36 |

| Fetal asphyxia | 35 (97.2%) |

| Lack of labor progression | 1 (2.8%) |

| >24–48 h | n = 26 |

| Fetal asphyxia | 22 (84.6%) |

| Lack of labor progression | 4 (15.4%) |

| >48 h | n = 4 |

| Fetal asphyxia | 1 (25.0%) |

| Lack of labor progression | 3 (75.0%) |

| BMI | 18.5–25 (n = 49) | 25.5–30 (n = 125) | 30–35 (n = 96) | 35–40 (n = 16) | >40 (n = 5) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD/CS 24 h | 35 (71.4%) | 79 (63.2%) | 58 (60.4%) | 7 (43.8%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0.255 |

| VD/CS > 24–48 h | 13 (26.5%) | 42 (33.6%) | 34 (35.4%) | 8 (50.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0.330 |

| VD/CS > 48 h | 1 (2.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 4 (4.2%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.906 |

| VD 24 h | 30 (71.4%) | 63 (63.6%) | 48 (66.7%) | 3 (37.5%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.0325 |

| VD 24–48 h | 11 (26.2%) | 33 (33.3%) | 22 (30.6%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.3995 |

| VD > 48 h | 1 (2.4%) | 3 (3.0%) | 2 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.9722 |

| CS 24 h | 5 (71.4%) | 16 (61.5%) | 10 (41.7%) | 4 (50.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0.525 |

| CS 24–48 h | 2 (28.6%) | 9 (34.6%) | 12 (50.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.217 |

| CS > 48 h | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 2 (8.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.377 |

| Oxytocin | 14 (28.6%) | 46 (36.8%) | 38 (39.6%) | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0.255 |

| First stage (h) | 0.189 | |||||

| range | 1.0–10.0 | 1.0–16.0 | 0.5–12.0 | 1.0–12.0 | 0.5–7.5 | |

| median (IRQ) | 3.0 (2.5) | 4.0 (3.5) | 3.5 (3.0) | 4.0 (3.0) | 6.5 (5.0) | |

| Second stage (h) | 0.426 | |||||

| range | 0.5–2.5 | 0.5–2.5 | 0.5–3.0 | 0.5–2.0 | 0.5–6.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.6) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (2.8) | |

| Analgesia | ||||||

| Remifentanil | 12 (24.5%) | 38 (30.4%) | 24 (25.0%) | 7 (43.8%) | 1 (20%) | 0.5256 |

| Epidural analgesia | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (24.8%) | 28 (29.2%) | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0.2252 |

| Tachysystole | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0157 |

| BMI | 18.5–25 (n = 49) | 25.5–30 (n = 125) | 30–35 (n = 96) | 35–40 (n = 16) | >40 (n = 5) | p-Value 1,2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRC (h) | 0.087 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 15.0 (12.3) | 16.8 (11.1) | 16.3 (11.2) | 21.5 (13.5) | 25.1 (10.1) | |

| range | 1.0–61.5 | 0.5–52.0 | 0.5–57.5 | 1.0–55.0 | 15.5–39.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 10.0 (20.5) | 14.0 (16.0) | 14.0 (16.0) | 22.5 (18.3) | 22.0 (15.0) | |

| 95%CI | [11.4; 18.5] | [14.8; 18.8] | [14.1; 18.6] | [14.3; 28.7] | [12.6; 37.6] | |

| TPO (h) | 0.077 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 14.9 (12.4) | 16.9 (11.1) | 16.4 (11.2) | 21.8 (13.7) | 25.1 (10.1) | |

| range | 1.0–61.5 | 0.5–52.0 | 0.5–58.0 | 1,0–55,0 | 15.5–39.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 10.0 (20.0) | 14.5 (16.0) | 14.0 (16.0) | 23.0 (18.3) | 22.0 (15.0) | |

| 95%CI | [11.4; 18.5] | [14.9; 18.8] | [14.1; 18.7] | [14.5; 29.1] | [12.6; 37.6] | |

| TD (h) | 0.058 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 19.3 (13.4) | 21.9 (11.9) | 21.5 (12.4) | 26.4 (15.3) | 31.5 (9.2) | |

| range | 1.5–70.0 | 4.0–58.0 | 2.5–68.0 | 2.0–59.0 | 22.0–42.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 14.5 (19.0) | 19.0 (17.5) | 19.0 (15.3) | 28.0 (23.0) | 30.0 (16.5) | |

| 95%CI | [15.4; 23.2] | [19.8; 24.0] | [19.0; 24.0] | [18.3; 34.5] | [20.1; 42.9] | |

| BL (mL) | 0.708 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 289.8 (137.7) | 314.0 (176.6) | 308.3 (118.0) | 340.6 (146.3) | 320.0 (103.7) | |

| range | 150.0–1 000.0 | 150.0–1 500.0 | 150.0–700.0 | 150.0–700.0 | 200.0–450.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 250.0 (100.0) | 250.0 (150.0) | 250.0 (175.0) | 300.0 (225.0) | 300.0 (150.0) | |

| 95%CI | [250.2; 329.3] | [282.6; 345.4] | [284.4; 332.2] | [262.7; 418.6] | [191.3; 448.7] | |

| PI | 0.670 | |||||

| 1 | 17 (51.5%) | 33 (42.3%) | 17 (30.9%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 15 (45.5%) | 43 (55.1%) | 36 (65.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (100.0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (3.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 18.5–25 (n = 49) | 25.5–30 (n = 125) | 30–35 (n = 96) | 35–40 (n = 16) | >40 (n = 5) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 min. | 0.088 | |||||

| range | 6.0–10.0 | 6.0–10.0 | 6.0–10.0 | 8.0–10.0 | 9.0–10.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.5) | 10.0 (0.0) | |

| 5 min. | 0.715 | |||||

| range | 7.0–10.0 | 8.0–10.0 | 8.0–10.0 | 9.0–10.0 | 10.0–10.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | |

| 10 min. | 0.623 | |||||

| range | 7.0–10.0 | 10.0–10.0 | 8.0–10.0 | 10.0–10.0 | 10.0–10.0 | |

| median (IRQ) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 (0.0) | |

| UA (pH) | 0.567 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 7.2 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.2 (0.1) | |

| range | 7.0–7.5 | 7.1–7.5 | 7.1–7.5 | 7.1–7.4 | 7.1–7.3 | |

| median (IRQ) | 7.2 (0.2) | 7.2 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.2) | 7.3 (0.1) | |

| 95%CI | [7.2; 7.3] | [7.2; 7.3] | [7.2; 7.3] | [7.2; 7.3] | [7.1; 7.4] | |

| UV (pH) | 0.544 | |||||

| mean (SD) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | |

| range | 7.0–7.5 | 7.1–7.5 | 7.1–7.6 | 7.1–7.4 | 7.2–7.4 | |

| median (IRQ) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | |

| 95%CI | [7.2; 7.3] | [7.3; 7.3] | [7.3; 7.3] | [7.3; 7.4] | [7.2; 7.4] |

| R | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| First stage of labor | 0.08 | 0.189 |

| Second stage of labor | −0.03 | 0.652 |

| Time to regular uterine contractions | 0.13 | 0.025 |

| Time to pain onset | 0.14 | 0.019 |

| Time to delivery | 0.15 | 0.013 |

| Blood loss | 0.07 | 0.203 |

| APGAR score at 1 min | 0.01 | 0.874 |

| APGAR score at 5 min | 0.03 | 0.596 |

| APGAR score at 10 min | 0.04 | 0.513 |

| pH UA | 0.10 | 0.095 |

| pH UV | 0.20 | 0.0005 |

| Initial Bishop score | −0.07 | 0.241 |

| Number of Misoprostol doses | 0.15 | 0.013 |

| Bishop score after Misoprostol administration | −0.17 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Socha, M.W.; Flis, W.; Sowińska, J.; Stankiewicz, M.; Kazdepka-Ziemińska, A. The Impact of Maternal BMI on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Misoprostol for Labor Induction. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121888

Socha MW, Flis W, Sowińska J, Stankiewicz M, Kazdepka-Ziemińska A. The Impact of Maternal BMI on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Misoprostol for Labor Induction. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121888

Chicago/Turabian StyleSocha, Maciej W., Wojciech Flis, Julia Sowińska, Martyna Stankiewicz, and Anita Kazdepka-Ziemińska. 2025. "The Impact of Maternal BMI on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Misoprostol for Labor Induction" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121888

APA StyleSocha, M. W., Flis, W., Sowińska, J., Stankiewicz, M., & Kazdepka-Ziemińska, A. (2025). The Impact of Maternal BMI on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Misoprostol for Labor Induction. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121888