The Therapeutic Effect of a Biodegradable Long-Acting Intravitreal Implant Containing CGK012 on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Promoting β-Catenin Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. CGK012 Promotes Pathogenic β-Catenin Degradation in RPE Cells

2.2. CGK012 Inhibits the Pathogenic Effects of β-Catenin in RPE Cells

2.3. CGK012 Inhibits the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway and Capillary Tube Formation in HUVECs

2.4. In Vitro Release and Intraocular Profile of CGK012-Loaded PLGA Implant

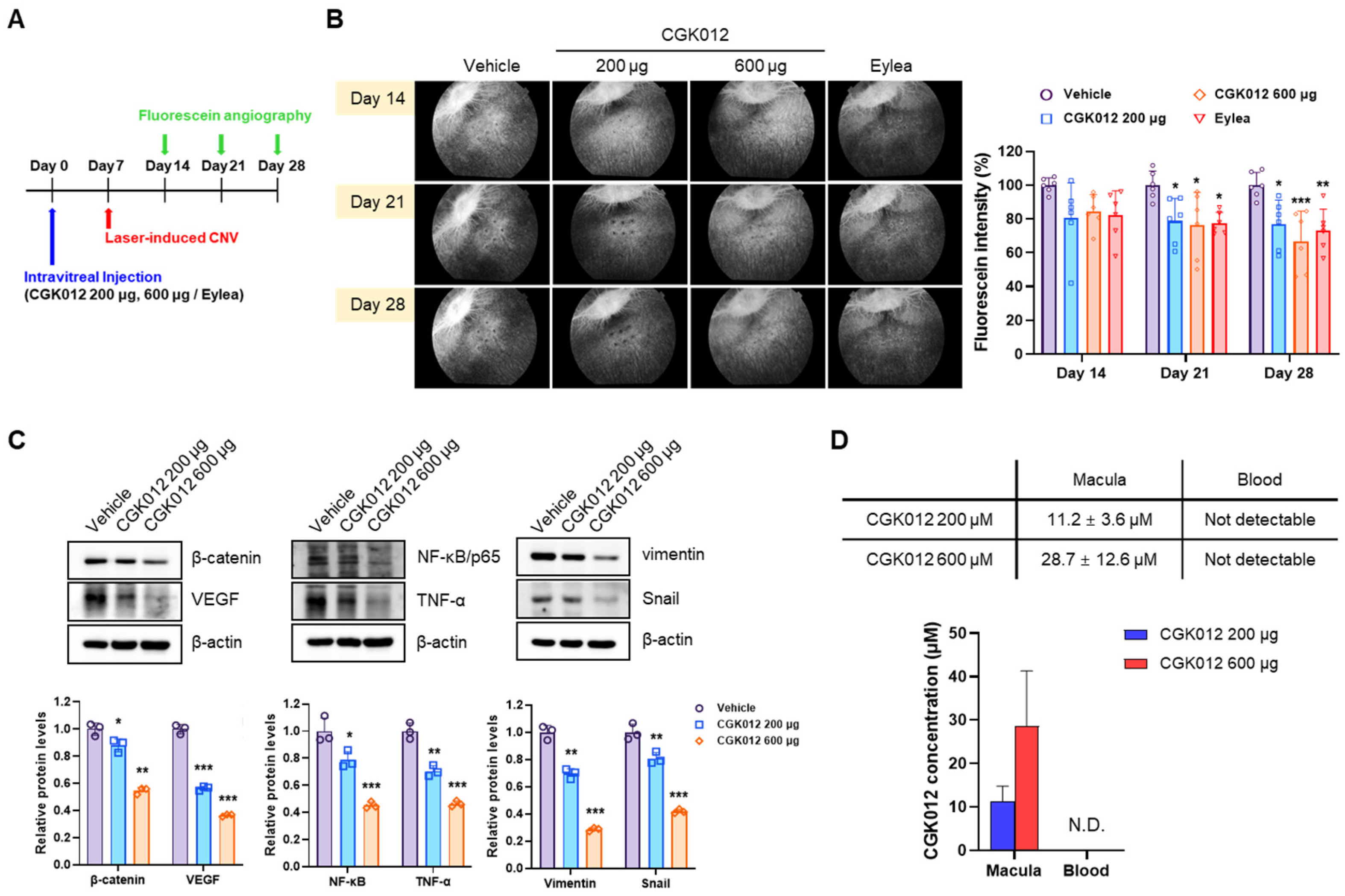

2.5. CGK012 Implants Inhibit Choroidal Neovascularization in a Rabbit Model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture, Transfection, Luciferase Assay, and Chemicals

4.2. Western Blot

4.3. Scratch Assay

4.4. Capillary Tube Formation Assay

4.5. CGK012-Loaded PLGA Implant Preparation

4.6. In Vitro Dissolution Test

4.7. Animals

4.8. CGK012-Loaded PLGA Implant Administration and Vitreous Sampling

4.9. Laser-Induced CNV Rabbit Model

4.10. Fluorescein Angiography and Neovascular Area Quantification

4.11. CGK012 Plasma and Macular Concentration

4.12. Data and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhutto, I.; Lutty, G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, S.; Koh, H.; Phil, M.; Henson, D.; Boulton, M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000, 45, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, A.J.; Kirchhof, J. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2009, 13, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campochiaro, P.A. Molecular pathogenesis of retinal and choroidal vascular diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015, 49, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.; Bressler, N.; Doan, Q.V.; Dolan, C.; Ferreira, A.; Osborne, A.; Rochtchina, E.; Danese, M.; Colman, S.; Wong, T.Y. Estimated cases of blindness and visual impairment from neovascular age-related macular degeneration avoided in Australia by ranibizumab treatment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrs, K.M.; Anderson, D.H.; Johnson, L.V.; Hageman, G.S. Age-related macular degeneration--emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann. Med. 2006, 38, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, P.S.; Schwartz, S.D.; Hubschman, J.P. Age-related macular degeneration: Current and novel therapies. Maturitas 2010, 66, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Llacer, H.; Heussen, F.M.; Joussen, A.M. Non-responders to bevacizumab (Avastin) therapy of choroidal neovascular lesions. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falavarjani, K.G.; Nguyen, Q.D. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: A review of literature. Eye 2013, 27, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.J.; Pohl, S.O.; Deshmukh, A.; Visweswaran, M.; Ward, N.C.; Arfuso, F.; Agostino, M.; Dharmarajan, A. The Role of Wnt Signalling in Angiogenesis. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2017, 38, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jridi, I.; Cante-Barrett, K.; Pike-Overzet, K.; Staal, F.J.T. Inflammation and Wnt Signaling: Target for Immunomodulatory Therapy? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 615131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: Types, Effects, Markers, Mechanisms for Disease Progression, and Its Relation with Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Gong, S.; Bai, X.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.X. Decreased Circulating Levels of Dickkopf-1 in Patients with Exudative Age-related Macular Degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, K.K.; Zhang, B.; Gao, G.; Ma, J.X. The pathogenic role of the canonical Wnt pathway in age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 4371–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, M.; Lee, K.; Mott, R.A.; Ma, J.X. Pathogenic role of the Wnt signaling pathway activation in laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Zhu, Y.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Tseng, S.C. Wnt signaling induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition with proliferation in ARPE-19 cells upon loss of contact inhibition. Lab. Investig. 2012, 92, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.Y.; Bang, J.Y.; Choi, A.J.; Yoon, J.; Lee, W.C.; Choi, S.; Yoon, S.; Kim, H.C.; Baek, J.H.; Park, H.S.; et al. Exosomal proteins in the aqueous humor as novel biomarkers in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, A.; Yoon, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, Y.M.; Park, H.; Lim, D.; Chung, H.; Kim, D.E. Autophagy and KRT8/keratin 8 protect degeneration of retinal pigment epithelium under oxidative stress. Autophagy 2017, 13, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.; Bao, S.; Wang, N.; Gillies, M.C. Diabetic macular edema: New concepts in patho-physiology and treatment. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackaberry, E.A.; Farman, C.; Zhong, F.; Lorget, F.; Staflin, K.; Cercillieux, A.; Miller, P.E.; Schuetz, C.; Chang, D.; Famili, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Toxicity of Intravitreally Injected PLGA Microspheres and Rods in Monkeys and Rabbits: Effects of Depot Size on Inflammatory Response. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 4274–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghjou, N.; Soheilian, M.; Abdekhodaie, M.J. Sustained release intraocular drug delivery devices for treatment of uveitis. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2011, 6, 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- jun Choi, P.; Yuseok, O.; Her, J.H.; Yun, E.; Song, G.Y.; Oh, S. Anti-proliferative activity of CGK012 against multiple myeloma cells via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling attenuation. Leuk. Res. 2017, 60, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Heo, J.B.; Heo, H.J.; Nam, G.; Song, G.Y.; Bae, J.S. The Beneficial Effects of CGK012 Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation. J. Med. Food 2025, 28, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, S.; Chung, H.; Oh, S. Wnt5a attenuates the pathogenic effects of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in human retinal pigment epithelial cells via down-regulating beta-catenin and Snail. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, M.; Xu, D.; Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, F. Overexpression of Snail in retinal pigment epithelial triggered epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.I.; Cho, H.J.; Hahn, J.Y.; Kim, T.Y.; Park, K.W.; Koo, B.K.; Shin, C.S.; Kim, C.H.; Oh, B.H.; Lee, M.M.; et al. Beta-catenin overexpression augments angiogenesis and skeletal muscle regeneration through dual mechanism of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated endothelial cell proliferation and progenitor cell mobilization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.G.; Wagner, M.G.; Wagner, A.L. The Sustained-Release Dexamethasone Implant: Expanding Indications in Vitreoretinal Disease. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 30, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colijn, J.M.; Buitendijk, G.H.S.; Prokofyeva, E.; Alves, D.; Cachulo, M.L.; Khawaja, A.P.; Cougnard-Gregoire, A.; Merle, B.M.J.; Korb, C.; Erke, M.G.; et al. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Europe: The Past and the Future. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 1753–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, S.; Chowdhury, H.; Elagouz, M.; Sivaprasad, S. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for age-related macular degeneration: A critical analysis of literature. Eye 2010, 24, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yafai, Y.; Yang, X.M.; Niemeyer, M.; Nishiwaki, A.; Lange, J.; Wiedemann, P.; King, A.G.; Yasukawa, T.; Eichler, W. Anti-angiogenic effects of the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, pazopanib, on choroidal neovascularization in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 666, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Roh, Y.J.; Kim, I.B. Antiangiogenic effects of tivozanib, an oral VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, on experimental choroidal neovascularization in mice. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 112, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, K.K.; Mott, R.; Wu, M.; Boulton, M.; Lyons, T.J.; Gao, G.; Ma, J.X. Activation of the Wnt pathway plays a pathogenic role in diabetic retinopathy in humans and animal models. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, R.; Lee, K.; Tyagi, P.; Ding, L.; Kompella, U.B.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, J.X. Nanoparticle-mediated expression of a Wnt pathway inhibitor ameliorates ocular neovascularization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Lim, D.; Park, S.; Song, I.S.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, S.; Jang, H.; Liu, K.H.; Song, G.Y.; Kang, W.; et al. Ilimaquinone inhibits neovascular age-related macular degeneration through modulation of Wnt/beta-catenin and p53 pathways. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Abreu, J.G.; Zhou, K.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, T.; He, X.; Ma, J.X. Blocking the Wnt pathway, a unifying mechanism for an angiogenic inhibitor in the serine proteinase inhibitor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6900–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegrini, D.; Raimondi, R.; Borgia, A.; Sorrentino, T.; Montesano, G.; Tsoutsanis, P.; Cancian, G.; Verma, Y.; De Rosa, F.P.; Romano, M.R. Curcumin in Retinal Diseases: A Comprehensive Review from Bench to Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, J.; Xie, H.; Tian, H.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C.; Xu, G.T.; Zhang, J. Wnt5a/beta-catenin-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A key driver of subretinal fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Storey, P.P.; Barakat, M.R.; Hershberger, V.; Bridges, W.Z., Jr.; Eichenbaum, D.A.; Lally, D.R.; Boyer, D.S.; Bakri, S.J.; Roy, M.; et al. Phase I DAVIO Trial: EYP-1901 Bioerodible, Sustained-Delivery Vorolanib Insert in Patients with Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbey, A.M.; Patel, S.S.; Barakat, M.; Hershberger, V.S.; Bridges, W.Z.; Eichenbaum, D.A.; Lally, D.; Storey, P.P.; Roy, M.; Duker, J.S.; et al. The DAVIO trial: A phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation study of a single injection of EYP-1901 (vorolanib in Durasert® platform) demonstrating reduced treatment burden in wet age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 931. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.G.; Chang, A.; Guymer, R.H.; Wickremasinghe, S.; Reilly, E.; Bell, N.; Vantipalli, S.; Moshfeghi, A.A.; Goldstein, M.H. Phase 1 Study of an Intravitreal Axitinib Hydrogel-based Implant for the Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (nAMD). Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, R.; Zhang, J.; Farooq, S.; Li, X.Y. Comparison of the release profile and pharmacokinetics of intact and fragmented dexamethasone intravitreal implants in rabbit eyes. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 30, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Semenov, M.; Han, C.; Baeg, G.H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, X.; He, X. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 2002, 108, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwak, J.; Cho, M.; Gong, S.J.; Won, J.; Kim, D.E.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.K.; Shin, J.G.; et al. Protein-kinase-C-mediated beta-catenin phosphorylation negatively regulates the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 4702–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.H.; Ahn, K.S.; Han, H.; Choung, S.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, I.H. Decursin and PDBu: Two PKC activators distinctively acting in the megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 human erythroleukemia cells. Leuk. Res. 2005, 29, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwak, J.; Lee, J.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Song, G.Y.; Oh, S. Small molecule-based promotion of PKCalpha-mediated beta-catenin degradation suppresses the proliferation of CRT-positive cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignam, J.D.; Lebovitz, R.M.; Roeder, R.G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983, 11, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.G.; Noh, K.; Song, G.Y.; Kang, W. Characterization of CGK012 in rat plasma by high performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS): Application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 189, 113458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Amo, E.M.; Urtti, A. Rabbit as an animal model for intravitreal pharmacokinetics: Clinical predictability and quality of the published data. Exp. Eye Res. 2015, 137, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.; Won, J.; Heo, J.B.; Kang, J.; Oh, Y.W.; Park, G.; Lee, G.; Lee, J.-H.; Song, G.-Y.; Kang, W.; et al. The Therapeutic Effect of a Biodegradable Long-Acting Intravitreal Implant Containing CGK012 on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Promoting β-Catenin Degradation. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121884

Park S, Won J, Heo JB, Kang J, Oh YW, Park G, Lee G, Lee J-H, Song G-Y, Kang W, et al. The Therapeutic Effect of a Biodegradable Long-Acting Intravitreal Implant Containing CGK012 on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Promoting β-Catenin Degradation. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121884

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Seoyoung, Jihyun Won, Jong Beom Heo, Juhyung Kang, Ye Woon Oh, Geunji Park, Giseong Lee, Jee-Hyun Lee, Gyu-Yong Song, Wonku Kang, and et al. 2025. "The Therapeutic Effect of a Biodegradable Long-Acting Intravitreal Implant Containing CGK012 on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Promoting β-Catenin Degradation" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121884

APA StylePark, S., Won, J., Heo, J. B., Kang, J., Oh, Y. W., Park, G., Lee, G., Lee, J.-H., Song, G.-Y., Kang, W., & Oh, S. (2025). The Therapeutic Effect of a Biodegradable Long-Acting Intravitreal Implant Containing CGK012 on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Promoting β-Catenin Degradation. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121884