Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy Penetration Depth in a Synthetic Pig Brain Model: A Novel Approach to Simulate the Reach of PDT-Mediated Effects In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Phantom Materials Attenuate Both Irradiance and the Inhibitory Effects on Spheroid Growth in a Thickness-Dependent Manner

2.2. PDT Predominantly Exerts a Sustained Inhibitory Effect on Spheroid Growth over Several Days

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Cultures and Growth Conditions

4.2. Spheroid Assay

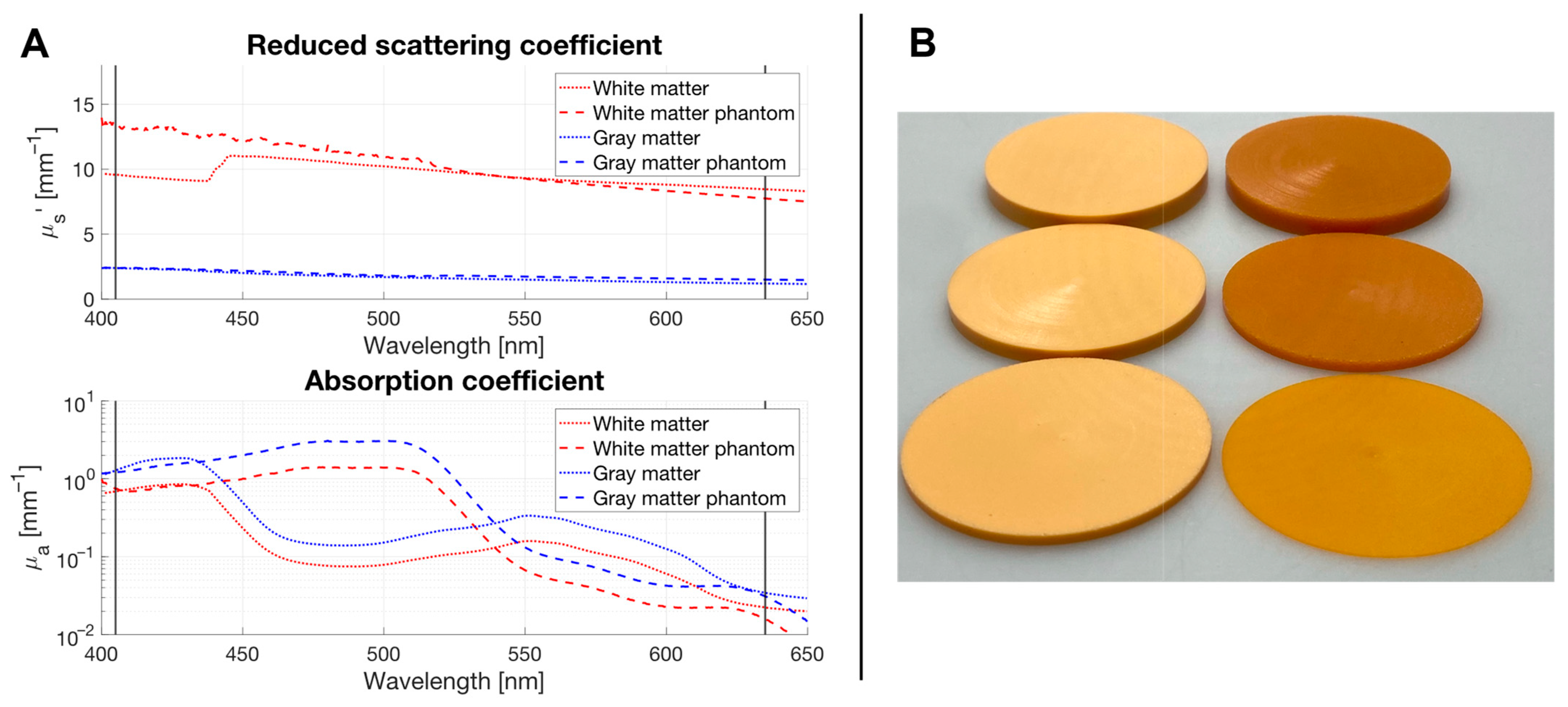

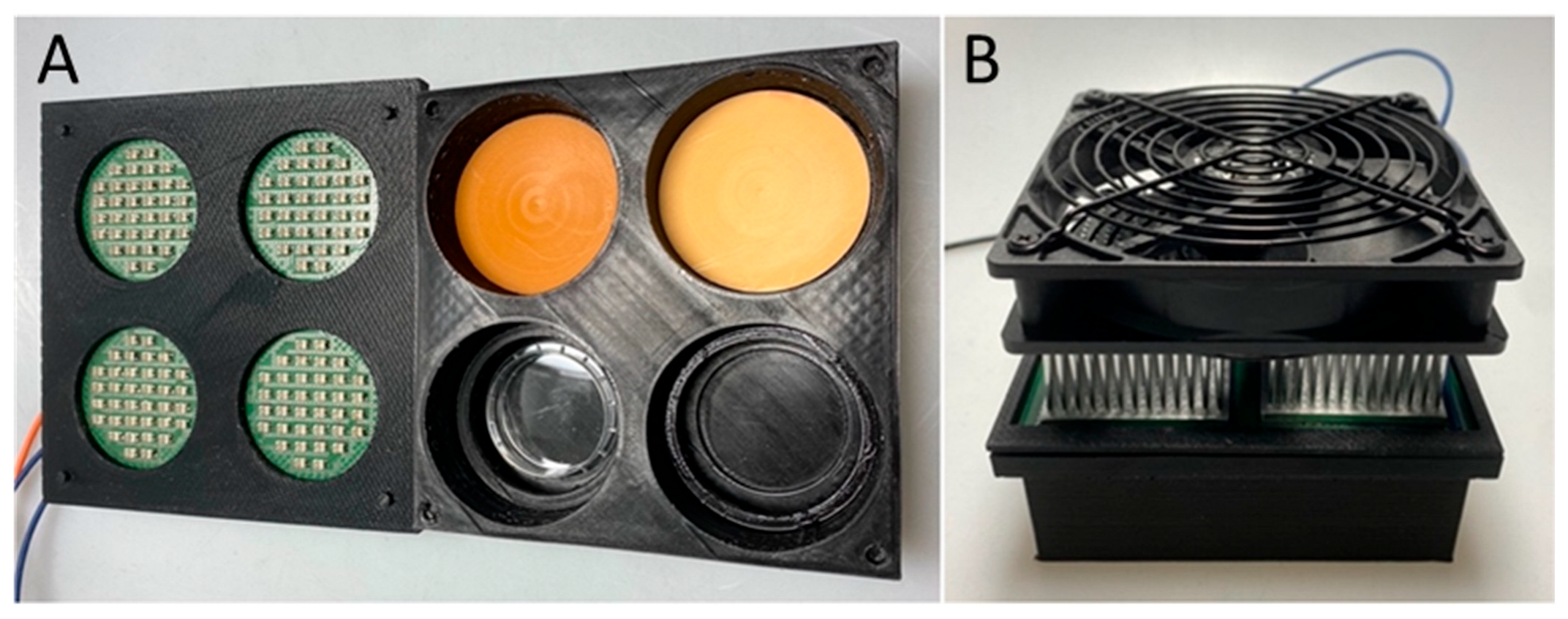

4.3. Optical Phantom Plates

4.4. Photodynamic Therapy

4.5. Light Intensiy Measurements

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-ALA | 5-Aminolevulinic acid |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PpIX | Protoporphyrin IX |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2014–2018. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, iii1–iii105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, J.; Fukami, S.; Suda, T.; Ichikawa, M.; Haraoka, R.; Kohno, M.; Shishido-Hara, Y.; Nagao, T.; Kuroda, M. First autopsy analysis of the efficacy of intra-operative additional photodynamic therapy for patients with glioblastoma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2019, 36, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A. Clinical uses of 5-aminolaevulinic acid in photodynamic treatment and photodetection of cancer: A review. Cancer Lett. 2020, 490, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostron, H.; Fiegele, T.; Akatuna, E. Combination of FOSCAN® mediated fluorescence guided resection and photodynamic treatment as new therapeutic concept for malignant brain tumors. Med. Laser Appl. 2006, 21, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wen, J.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Wen, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of fluorescent-guided resection and therapy-based photodynamics on the survival of patients with glioma. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Aguilar, L.; Vilchez, M.L.; Milla Sanabria, L.N. Targeting glioblastoma stem cells: The first step of photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 36, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepp, H.; Beck, T.; Pongratz, T.; Meinel, T.; Kreth, F.-W.; Tonn, J.C.; Stummer, W. ALA and malignant glioma: Fluorescence-guided resection and photodynamic treatment. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2007, 26, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stummer, W.; Pichlmeier, U.; Meinel, T.; Wiestler, O.D.; Zanella, F.; Reulen, H.-J. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: A randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, K.W.; Lee, S.H. Characterization of Protoporphyrin IX Species in Vitro Using Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Polar Plot Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 5832–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, R.M.; Ibbotson, S.H.; Wood, K.; Brown, C.T.A.; Moseley, H. Modelling fluorescence in clinical photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, S.W.; Chen, C.C. Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Front. Surg. 2020, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: An Update. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, S.; Demirs, J.T.; Kochevar, I.E. Protein kinase C inhibits singlet oxygen-induced apoptosis by decreasing caspase-8 activation. Oncogene 2001, 20, 6764–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.-B.; Oh, G.-S.; Scandella, E.; Bolinger, B.; Ludewig, B.; Kovalenko, A.; Wallach, D. Mutation of a self-processing site in caspase-8 compromises its apoptotic but not its nonapoptotic functions in bacterial artificial chromosome-transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 2522–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kischkel, F.C.; Hellbardt, S.; Behrmann, I.; Germer, M.; Pawlita, M.; Krammer, P.H.; Peter, M.E. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 5579–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stennicke, H.R.; Jürgensmeier, J.M.; Shin, H.; Deveraux, Q.; Wolf, B.B.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ellerby, H.M.; Ellerby, L.M.; Bredesen, D.; et al. Pro-caspase-3 Is a Major Physiologic Target of Caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 27084–27090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, Q. Caspase-9: Structure, mechanisms and clinical application. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23996–24008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Pinedo, C.; Guío-Carrión, A.; Goldstein, J.C.; Fitzgerald, P.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Green, D.R. Different mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins are released during apoptosis in a manner that is coordinately initiated but can vary in duration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11573–11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, Y.-L.P.; Green, D.R.; Hao, Z.; Mak, T.W. Cytochrome c: Functions beyond respiration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, S.W.G.; Green, D.R. Mitochondria and cell death: Outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysart, J.S.; Patterson, M.S. Characterization of Photofrin photobleaching for singlet oxygen dose estimation during photodynamic therapy of MLL cells in vitro. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 2597–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, P.S.; Bhattarai, H.K. Singlet Oxygen, Photodynamic Therapy, and Mechanisms of Cancer Cell Death. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 7211485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, H.; Murayama, Y.; Nakanishi, M.; Inoue, K.; Nakajima, M.; Otsuji, E. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy using light-emitting diodes of different wavelengths in a mouse model of peritoneally disseminated gastric cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 185, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Song, C.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, D.W. Light-Emitting Diode Laser Versus Pulsed Dye Laser-Assisted Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis and Bowen’s Disease. Dermatol. Surg. 2012, 38, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Peschmann, C.; Kast, R.E.; Heiland, T.; Merz, T.; McCook, O.; Alfieri, A.; Karpel-Massler, G.; Capanni, F.; Halatsch, M.-E. Globus Lucidus: A porcine study of an intracranial implant designed to deliver closed, repetitive photodynamic and photochemical therapy in glioblastoma. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 46, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kijanska, M.; Kelm, J. (Eds.) In vitro 3D Spheroids and Microtissues: ATP-based Cell Viability and Toxicity Assays. In The Assay Guidance Manual; Eli Lilly & Company: Indianapolis, IN, USA; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kleijn, A.; Kloezeman, J.J.; Balvers, R.K.; van der Kaaij, M.; Dirven, C.M.F.; Leenstra, S.; Lamfers, M.L.M. A Systematic Comparison Identifies an ATP-Based Viability Assay as Most Suitable Read-Out for Drug Screening in Glioma Stem-Like Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5623235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermandel, M.; Dupont, C.; Lecomte, F.; Leroy, H.-A.; Tuleasca, C.; Mordon, S.; Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Reyns, N. Standardized intraoperative 5-ALA photodynamic therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients: A preliminary analysis of the INDYGO clinical trial. J. Neurooncol. 2021, 152, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peciu-Florianu, I.; Vannod-Michel, Q.; Vauleon, E.; Bonneterre, M.-E.; Reyns, N. Long term follow-up of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated by intraoperative photodynamic therapy: An update from the INDYGO trial (NCT03048240). J. Neurooncol. 2024, 168, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, S.; Lanka, P.; Stone, N.; Konugolu Venkata Sekar, S.; Matousek, P.; Valentini, G.; Pifferi, A. Optical characterization of porcine tissues from various organs in the 650–1100 nm range using time-domain diffuse spectroscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2020, 11, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, S.L. Optical properties of biological tissues: A review. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, R37–R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzmaier, H.-J.; Yaroslavsky, A.N.; Yaroslavsky, I.V.; Goldbach, T.; Kahn, T.; Ulrich, F.; Schulze, P.C.; Schober, R. Optical properties of native and coagulated human brain structures. SPIE 2970 Lasers Surg. Adv. Charact. Ther. Syst. 1997, 2970, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgie, B.N.; Prakash, R.; Goyeneche, A.A.; Telleria, C.M. Vitality, viability, long-term clonogenic survival, cytotoxicity, cytostasis and lethality: What do they mean when testing new investigational oncology drugs? Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirk, B.J.; Brandal, G.; Donlon, S.; Vera, J.C.; Mang, T.S.; Foy, A.B.; Lew, S.M.; Girotti, A.W.; Jogal, S.; LaViolette, P.S.; et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) for malignant brain tumors—Where do we stand? Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2015, 12, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.; Dale, A.M. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11050–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisi, G.; Mangiola, A. Current Knowledge about the Peritumoral Microenvironment in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, M.; Bellnier, D.A.; Vaughan, L.A.; Spernyak, J.A.; Mazurchuk, R.; Foster, T.H.; Henderson, B.W. Light delivery over extended time periods enhances the effectiveness of photodynamic therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, M.S.; Angell-Petersen, E.; Sanchez, R.; Sun, C.-H.; Vo, V.; Hirschberg, H.; Madsen, S.J. The effects of ultra low fluence rate single and repetitive photodynamic therapy on glioma spheroids. Lasers Surg. Med. 2009, 41, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-W.; Lin, L.-T.; Chen, P.-H.; Ho, M.-H.; Huang, W.-T.; Lee, Y.-J.; Chiou, S.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-S.; Dong, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-W. Low-fluence rate, long duration photodynamic therapy in glioma mouse model using organic light emitting diode (OLED). Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2015, 12, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Nguyen, L.; Le, M.T.; Ju, D.; Le, J.N.; Berg, K.; Hirschberg, H. The effects of low irradiance long duration photochemical internalization on glioma spheroids. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpel-Massler, G.; Kast, R.E.; Westhoff, M.-A.; Dwucet, A.; Welscher, N.; Nonnenmacher, L.; Hlavac, M.; Siegelin, M.D.; Wirtz, C.R.; Debatin, K.-M.; et al. Olanzapine inhibits proliferation, migration and anchorage-independent growth in human glioblastoma cell lines and enhances temozolomide’s antiproliferative effect. J. Neurooncol. 2015, 122, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ströbele, S.; Schneider, M.; Schneele, L.; Siegelin, M.D.; Nonnenmacher, L.; Zhou, S.; Karpel-Massler, G.; Westhoff, M.-A.; Halatsch, M.-E.; Debatin, K.-M. A Potential Role for the Inhibition of PI3K Signaling in Glioblastoma Therapy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Ströbele, S.; Nonnenmacher, L.; Siegelin, M.D.; Tepper, M.; Stroh, S.; Hasslacher, S.; Enzenmüller, S.; Strauss, G.; Baumann, B.; et al. A paired comparison between glioblastoma “stem cells” and differentiated cells. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnenmacher, L.; Westhoff, M.-A.; Fulda, S.; Karpel-Massler, G.; Halatsch, M.-E.; Engelke, J.; Simmet, T.; Corbacioglu, S.; Debatin, K.-M. RIST: A potent new combination therapy for glioblastoma. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E173–E187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, F.; Foschum, F.; Marzel, L.; Kienle, A. Ex Vivo Determination of Broadband Absorption and Effective Scattering Coefficients of Porcine Tissue. Photonics 2021, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, P.; Mitchell, P.; Watkins, C.; Matcham, J. Decision-making in early clinical drug development. Pharm. Stat. 2016, 15, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Thickness of Phantom Material [mm] | Irradiance “White Matter” [mW/cm2] | Irradiance “Gray Matter” [mW/cm2] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.85 | 6.14 |

| 2 | 1.29 | 3.78 |

| 3 | 0.70 | 2.57 |

| 4 | 0.38 | - |

| 5 | 0.21 | 1.29 |

| 6 | 0.13 | - |

| 7 | - | 0.48 |

| 9 | - | 0.25 |

| Cell line | Diagnosis | Location | Age at Diagnosis | Sex | MGMT | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U251MG | Glioblastoma WHO IV | Left parieto-occipital | 47 | M | N/A | Established commercially available cell line |

| T98G | Glioblastoma WHO IV | N/A | 61 | M | +,[45] | Established commercially available cell line |

| SC38 | Glioblastoma WHO IV | Right temporal | 75 | M | −,[44,45] | Established as spheroids from patient material |

| SC40 | Glioblastoma WHO IV | Left frontal | 57 | F | −,[44,45] | Established as spheroids from patient material |

| PC38 | Glioblastoma WHO IV | Right temporal | 75 | M | −,[44,45] | Differentiated from SC38 under exposure to FBS |

| PC40 | Glioblastoma WHO IV | Left frontal | 57 | F | −,[44,45] | Differentiated from SC40 under exposure to FBS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bader, N.; Hajosch, A.; Peschmann, C.; Stucke-Straub, K.; Wirtz, C.R.; Kast, R.E.; Halatsch, M.-E.; Capanni, F.; Karpel-Massler, G. Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy Penetration Depth in a Synthetic Pig Brain Model: A Novel Approach to Simulate the Reach of PDT-Mediated Effects In Vitro. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121837

Bader N, Hajosch A, Peschmann C, Stucke-Straub K, Wirtz CR, Kast RE, Halatsch M-E, Capanni F, Karpel-Massler G. Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy Penetration Depth in a Synthetic Pig Brain Model: A Novel Approach to Simulate the Reach of PDT-Mediated Effects In Vitro. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121837

Chicago/Turabian StyleBader, Nicolas, Annika Hajosch, Christian Peschmann, Kathrin Stucke-Straub, Christian Rainer Wirtz, Richard Eric Kast, Marc-Eric Halatsch, Felix Capanni, and Georg Karpel-Massler. 2025. "Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy Penetration Depth in a Synthetic Pig Brain Model: A Novel Approach to Simulate the Reach of PDT-Mediated Effects In Vitro" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121837

APA StyleBader, N., Hajosch, A., Peschmann, C., Stucke-Straub, K., Wirtz, C. R., Kast, R. E., Halatsch, M.-E., Capanni, F., & Karpel-Massler, G. (2025). Assessment of Photodynamic Therapy Penetration Depth in a Synthetic Pig Brain Model: A Novel Approach to Simulate the Reach of PDT-Mediated Effects In Vitro. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121837