Bioengineering Stem Cell-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Development of Glioblastoma Tumor Microenvironment Parallels in Brain Healthy Brain Neurogenesis

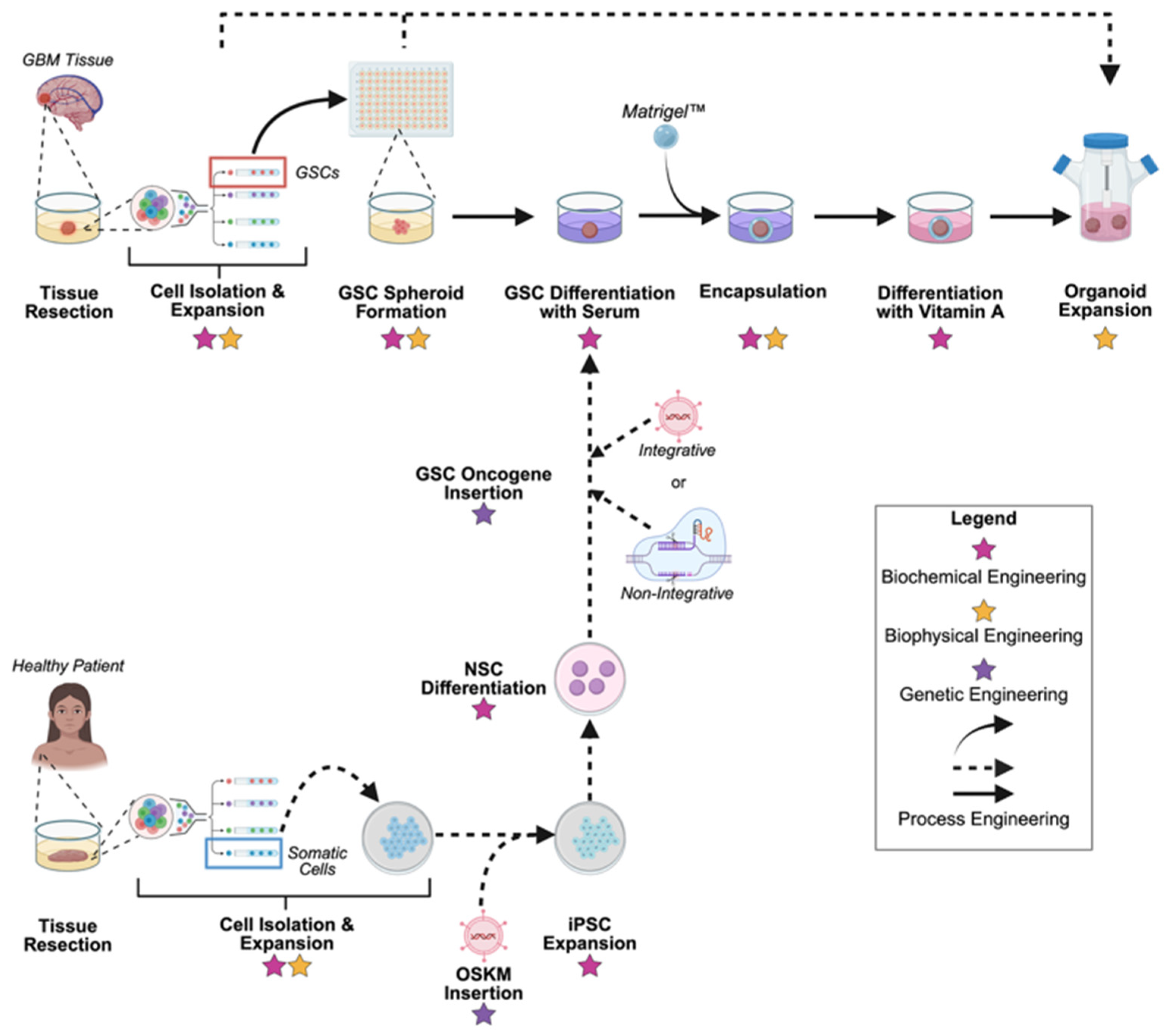

2.1. Healthy Neurogenesis

2.2. Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

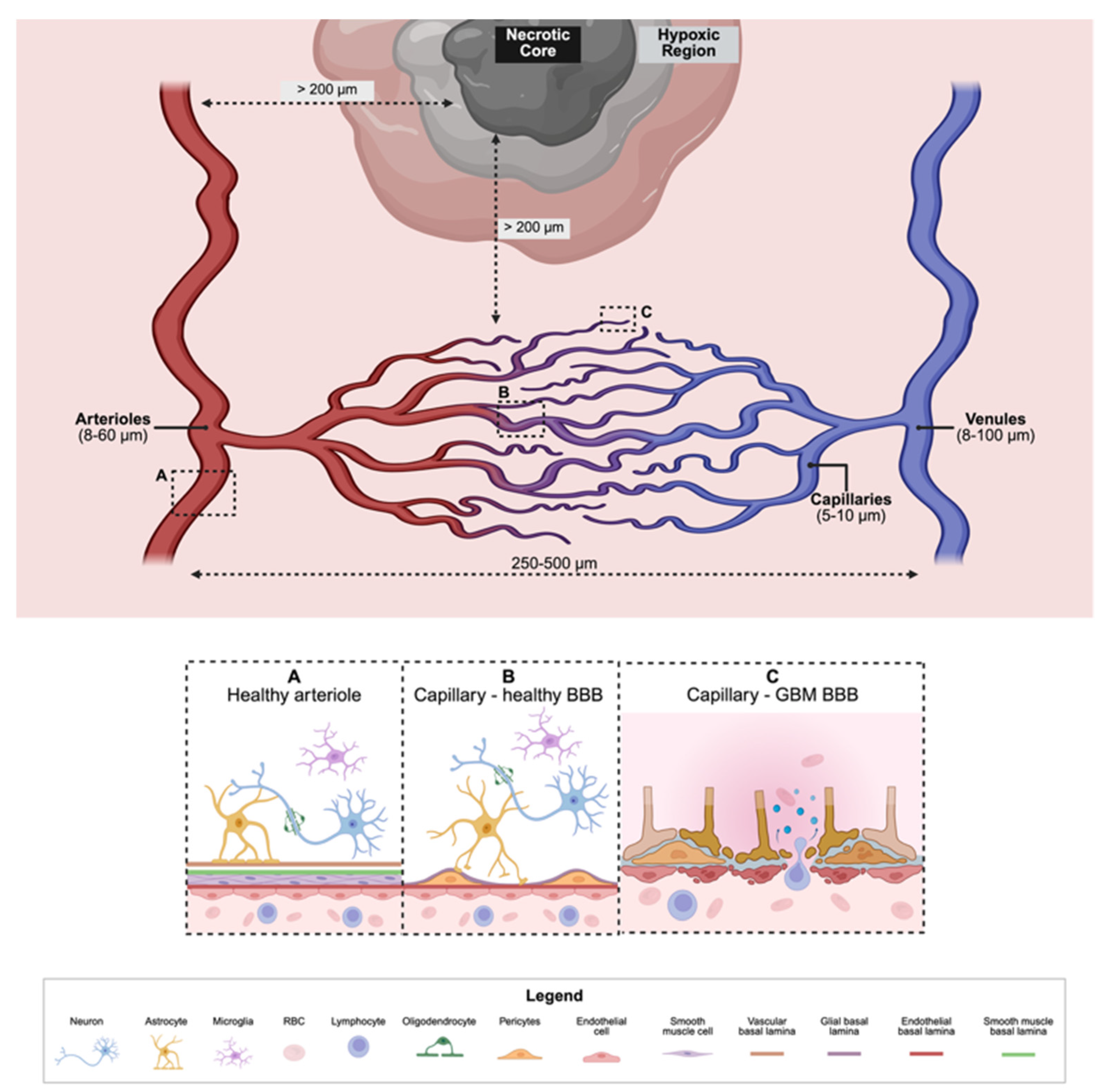

2.3. The Neurovascular Unit (NVU)

2.4. The Brain’s Immune System

3. Critical Limitations in Physiological Relevance Have Triggered the Advancement of In Vitro Modeling Systems of Glioblastoma

3.1. Two-Dimensional (2D) In Vitro Systems

3.2. Three-Dimensional (3D) In Vitro Systems

3.3. Organoids

4. Bioengineering Perspectives on Glioblastoma Organoid Fabrication and Control

4.1. Genetic Engineering

4.2. Biochemical Engineering

4.3. Biophysical Engineering

4.4. Process Engineering

5. Translational Gaps in Glioblastoma Organoid Development

5.1. Standardization

5.2. Enhanced Readouts

5.3. Logistics

6. Discussion: Current Tradeoffs and Needs in GBO Development

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| ACs | Astrocyte Cells |

| ATRX | Alpha-thalassemia/intellectual disability X-linked |

| BBB | Blood-Brain-Barrier |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CPA | Cryoprotective Agent |

| CSC | Cancer Stem Cell |

| CSPG | Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| ECs | Endothelial Cells |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| EGFRvIII | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor vIII |

| ESCs | Embryonic Stem Cells |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| GBM | Glioblastoma (multiforme) |

| GBO | Glioblastoma Organoid |

| GSC | GBM Stem Cell |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid |

| IDH | Isocitrate Dehydrogenase |

| IDH1 | Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 |

| iPSCs | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| LC-MS | Liquid-Chromatography Mass-Spectrometry |

| LGG | Lower-Grade Glioma |

| NPCs | Neural Progenitor Cells |

| NSCs | Neural Stem Cells |

| NVU | Neurovascular Unit |

| OSKM | OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC |

| PCs | Pericyte Cells |

| PNNs | Perineuronal Nets |

| PSCs | Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| QC | Quality Control |

| RGs | Radial Glial Cells |

| RNA-seq | Ribonucleic Acid Sequencing |

| SOM | Standardized Organoid Modeling (National Institute of Health Center) |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedure |

| TAMs | Tumor Associated Microglia |

| TCPS | Tissue Culture Polystyrene |

| TERT | Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNC | Tenascin-C |

| TP53 | Tumor Protein P53 |

| ULA | Ultra-low Attachment |

References

- van Linde, M.E.; Brahm, C.G.; de Witt Hamer, P.C.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Bruynzeel, A.M.E.; Vandertop, W.P.; van de Ven, P.M.; Wagemakers, M.; van der Weide, H.L.; Enting, R.H.; et al. Treatment outcome of patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A retrospective multicenter analysis. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 135, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, Y.W.; Santosh, K. Medical Progress: Malignant Gliomas in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandery, E. Glioblastoma Treatments: An Account of Recent Industrial Developments. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, A.R.; Cirigliano, S.M.; Nicholson, J.G.; Hu, Y.; Linkous, A.; Miyaguchi, K.; Edwards, L.; Singhania, R.; Schwartz, T.H.; Ramakrishna, R.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment Is Critical for the Maintenance of Cellular States Found in Primary Glioblastomas. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, K.J.; Chen, J.; Coombes, J.; Aghi, M.K.; Kumar, S. Dissecting and rebuilding the glioblastoma microenvironment with engineered materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.I.; Song, H.; Ming, G.-L. Applications of Human Brain Organoids to Clinical Problems. Dev. Dyn. 2019, 248, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, L.; Luo, L.; Shu, L.; Si, X.; Chen, Z.; Xia, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shao, A.; et al. Opportunities and challenges of glioma organoids. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Avera, A.D.; Kim, Y. Biomanufacturing of glioblastoma organoids exhibiting hierarchical and spatially organized tumor microenvironment via transdifferentiation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 3252–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, C.G.; Rivera, M.; Spangler, L.C.; Wu, Q.; Mack, S.C.; Prager, B.C.; Couce, M.; McLendon, R.E.; Sloan, A.E.; Rich, J.N. A Three-Dimensional Organoid Culture System Derived from Human Glioblastomas Recapitulates the Hypoxic Gradients and Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity of Tumors Found In Vivo. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, V.; Pospisilova, V.; Vanova, T.; Amruz Cerna, K.; Abaffy, P.; Sedmik, J.; Raska, J.; Vochyanova, S.; Matusova, Z.; Houserova, J.; et al. Glioblastoma and cerebral organoids: Development and analysis of an in vitro model for glioblastoma migration. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkous, A.; Balamatsias, D.; Snuderl, M.; Edwards, L.; Miyaguchi, K.; Milner, T.; Reich, B.; Cohen-Gould, L.; Storaska, A.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Modeling Patient-Derived Glioblastoma with Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3203–3211.e3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, P.; Choi, N.Y.; Shrestha, S.; Jeong, S.; Lee, M.Y. Brain organoids: A revolutionary tool for modeling neurological disorders and development of therapeutics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, M.; Lutolf, M.P. Engineering organoids. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Mead, B.E.; Safaee, H.; Langer, R.; Karp, J.M.; Levy, O. Engineering Stem Cell Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.; Dowbaj, A.M.; Sljukic, A.; Bratlie, K.; Lin, L.; Fong, E.L.S.; Balachander, G.M.; Chen, Z.; Soragni, A.; et al. Organoids. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.-S.; Chen, H.-M.; Yang, M.-Y.; Zhang, C.-B.; Yu, K.; Ye, W.-L.; Hu, B.-Q.; Yan, W.; Zhang, W.; Akers, J.; et al. RNA-seq of 272 gliomas revealed a novel, recurrent PTPRZ1-MET fusion transcript in secondary glioblastomas. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccarelli, M.; Barthel, F.P.; Malta, T.M.; Sabedot, T.S.; Salama, S.R.; Murray, B.A.; Morozova, O.; Newton, Y.; Radenbaugh, A.; Pagnotta, S.M.; et al. Molecular Profiling Reveals Biologically Discrete Subsets and Pathways of Progression in Diffuse Glioma. Cell 2016, 164, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesluk, M.; Pogoda, K.; Deptula, P.; Werel, P.; Kulakowska, A.; Kochanowicz, J.; Mariak, Z.; Lyson, T.; Reszec, J.; Bucki, R. Nanomechanics and Histopathology as Diagnostic Tools to Characterize Freshly Removed Human Brain Tumors. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 7509–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeckle, K.A.; Decker, P.A.; Ballman, K.V.; Flynn, P.J.; Giannini, C.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Jenkins, R.B.; Buckner, J.C. Transformation of low grade glioma and correlation with outcome: An NCCTG database analysis. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 104, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B. Prediction and analysis of hub genes between glioblastoma and low-grade glioma using bioinformatics analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e23513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Q.; Donnola, S.; Liu, J.K.; Fang, X.; Sloan, A.E.; Mao, Y.; Lathia, J.D.; et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell 2013, 153, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, B.C.; Bhargava, S.; Mahadev, V.; Hubert, C.G.; Rich, J.N. Glioblastoma Stem Cells: Driving Resilience through Chaos. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.K. Normalizing Tumor Microenvironment to Treat Cancer: Bench to Bedside to Biomarkers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2205–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, D.F.; Joyce, J.A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.; Stewart, K.M.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 4195–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbereis, J.C.; Pochareddy, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Sestan, N. The Cellular and Molecular Landscapes of the Developing Human Central Nervous System. Neuron 2016, 89, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penisson, M.; Ladewig, J.; Belvindrah, R.; Francis, F. Genes and Mechanisms Involved in the Generation and Amplification of Basal Radial Glial Cells. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Sun, Y.; Resto-Irizarry, A.M.; Yuan, Y.; Aw Yong, K.M.; Zheng, Y.; Weng, S.; Shao, Y.; Chai, Y.; Studer, L.; et al. Mechanics-guided embryonic patterning of neuroectoderm tissue from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, H.S.; Kharbanda, S.; Chen, R.; Forrest, W.F.; Soriano, R.H.; Wu, T.D.; Misra, A.; Nigro, J.M.; Colman, H.; Soroceanu, L.; et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.H.; Park, J.S.; Park, J.; Choi, S.H. Assessing the reproducibility of high temporal and spatial resolution dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with gliomas. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faissner, A.; Reinhard, J. The extracellular matrix compartment of neural stem and glial progenitor cells. Glia 2015, 63, 1330–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.H. Genetic Architectures and Cell-of-Origin in Glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 615400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, R.; Binda, E.; Orfanelli, U.; Cipelletti, B.; Gritti, A.; De Vitis, S.; Fiocco, R.; Foroni, C.; Dimeco, F.; Vescovi, A. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7011–7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, A.; Donato, A.; Bria, J.; Conforti, F.; La Torre, D.; Malara, N.; Donato, G. Extracellular Matrix Structure and Interaction with Immune Cells in Adult Astrocytic Tumors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin, E.; Wakimoto, H. Extracellular matrix in glioblastoma: Opportunities for emerging therapeutic approaches. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 3742–3754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lam, D.; Enright, H.A.; Cadena, J.; Peters, S.K.G.; Sales, A.P.; Osburn, J.J.; Soscia, D.A.; Kulp, K.S.; Wheeler, E.K.; Fischer, N.O. Tissue-specific extracellular matrix accelerates the formation of neural networks and communities in a neuron-glia co-culture on a multi-electrode array. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Sohrabi, A.; Seidlits, S.K. Integrating the glioblastoma microenvironment into engineered experimental models. Future Sci. OA 2017, 3, FSO189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanska, A.; Grall, D.; Schaub, S.; Divonne, S.B.-d.l.F.; Ciais, D.; Rekima, S.; Rupp, T.; Sudaka, A.; Orend, G.; Van Obberghen-Schilling, E. Counterbalancing anti-adhesive effects of Tenascin-C through fibronectin expression in endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidoe-Ansah, D.; Mirzapourdelavar, H.; Aleshin, S.; Schott, B.H.; Seidenbecher, C.; Kaushik, R.; Dityatev, A. Neurocan regulates axon initial segment organization and neuronal activity. Matrix Biol. 2025, 136, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.H.; Brakebusch, C.; Matthies, H.; Oohashi, T.; Hirsch, E.; Moser, M.; Krug, M.; Seidenbecher, C.I.; Boeckers, T.M.; Rauch, U.; et al. Neurocan is dispensable for brain development. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 5970–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, U.; Kaye, A.H. Extracellular matrix and the brain: Components and function. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 7, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, A.; Titov, S.; Shved, N.; Garbuz, M.; Malykin, G.; Gulaia, V.; Kagansky, A.; Kumeiko, V. The Extracellular Matrix and Biocompatible Materials in Glioblastoma Treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmelova, M.; Androvic, P.; Kirdajova, D.; Tureckova, J.; Kriska, J.; Valihrach, L.; Anderova, M.; Vargova, L. A view of the genetic and proteomic profile of extracellular matrix molecules in aging and stroke. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1296455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avera, A.D.; Gibson, D.J.; Birge, M.L.; Schnorbus, T.N.; Concannon, I.M.; Kim, Y. Characterization of Native Extracellular Matrix of Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Multiforme Organoids. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2025, 31, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Nirwane, A.; Yao, Y. Basement membrane and blood-brain barrier. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2019, 4, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serres, E.; Debarbieux, F.; Stanchi, F.; Maggiorella, L.; Grall, D.; Turchi, L.; Burel-Vandenbos, F.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Virolle, T.; Rougon, G.; et al. Fibronectin expression in glioblastomas promotes cell cohesion, collective invasion of basement membrane in vitro and orthotopic tumor growth in mice. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3451–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Obberghen-Schilling, E.; Tucker, R.P.; Saupe, F.; Gasser, I.; Cseh, B.; Orend, G. Fibronectin and tenascin-C: Accomplices in vascular morphogenesis during development and tumor growth. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J.W.; Oohashi, T.; Pizzorusso, T. The roles of perineuronal nets and the perinodal extracellular matrix in neuronal function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Miller, J.H. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, S.; Yong, V.W. The extracellular matrix as modifier of neuroinflammation and remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2021, 144, 1958–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, J.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y. The role of pericytic laminin in blood brain barrier integrity maintenance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simao, D.; Silva, M.M.; Terrasso, A.P.; Arez, F.; Sousa, M.F.Q.; Mehrjardi, N.Z.; Saric, T.; Gomes-Alves, P.; Raimundo, N.; Alves, P.M.; et al. Recapitulation of Human Neural Microenvironment Signatures in iPSC-Derived NPC 3D Differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 11, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anazco, C.; Lopez-Jimenez, A.J.; Rafi, M.; Vega-Montoto, L.; Zhang, M.Z.; Hudson, B.G.; Vanacore, R.M. Lysyl Oxidase-like-2 Cross-links Collagen IV of Glomerular Basement Membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 25999–26012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammoto, T.; Jiang, A.; Jiang, E.; Panigrahy, D.; Kieran, M.W.; Mammoto, A. Role of Collagen Matrix in Tumor Angiogenesis and Glioblastoma Multiforme Progression. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 183, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, M.D.A.; Ferreira, S.A.; Jowett, G.M.; Bozec, L.; Gentleman, E. Measuring the elastic modulus of soft culture surfaces and three-dimensional hydrogels using atomic force microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 2418–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.J.; Sen, S.; Sweeney, H.L.; Discher, D.E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 2006, 126, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, J.B.; El-Ashry, D.; Turley, E.A. Hyaluronan, Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and the Tumor Microenvironment in Malignant Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarians, G.; Sohrabi, A.; Solomon, I.; Xiao, W.; Bastola, S.; Rajput, B.W.; Epperson, M.; Rosenzweig, I.; Tamura, K.; Singer, B.; et al. Glioblastoma Spheroid Invasion through Soft, Brain-Like Matrices Depends on Hyaluronic Acid–CD44 Interactions. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2203143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.K.; Lee, H.G.; Schwertfeger, K.L.; McCarthy, J.B.; Turley, E.A. The Content and Size of Hyaluronan in Biological Fluids and Tissues. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-F.; Qiao, S.-P.; Shi, S.-L.; Yao, L.-F.; Hou, X.-L.; Li, C.-F.; Lin, F.-H.; Guo, K.; Acharya, A.; Chen, X.-B.; et al. Modulating Three-Dimensional Microenvironment with Hyaluronan of Different Molecular Weights Alters Breast Cancer Cell Invasion Behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 9327–9338, Erratum in ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 43979–43980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, I.; Cha, J.; Park, J.; Choi, J.; Kang, S.G.; Kim, P. The mode and dynamics of glioblastoma cell invasion into a decellularized tissue-derived extracellular matrix-based three-dimensional tumor model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between Hyaluronan and Its Receptors (CD44, RHAMM) Regulate the Activities of Inflammation and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walchli, T.; Bisschop, J.; Carmeliet, P.; Zadeh, G.; Monnier, P.P.; De Bock, K.; Radovanovic, I. Shaping the brain vasculature in development and disease in the single-cell era. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.J.; Heiman, M. Molecular and cellular characteristics of cerebrovascular cell types and their contribution to neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, F.J.; Sun, N.; Lee, H.; Godlewski, B.; Mathys, H.; Galani, K.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, X.; Ng, A.P.; Mantero, J.; et al. Single-cell dissection of the human brain vasculature. Nature 2022, 603, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walchli, T.; Ghobrial, M.; Schwab, M.; Takada, S.; Zhong, H.; Suntharalingham, S.; Vetiska, S.; Gonzalez, D.R.; Wu, R.; Rehrauer, H.; et al. Single-cell atlas of the human brain vasculature across development, adulthood and disease. Nature 2024, 632, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirwane, A.; Yao, Y. Cell-specific expression and function of laminin at the neurovascular unit. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2022, 42, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.S.; Foster, C.G.; Courtney, J.-M.; King, N.E.; Howells, D.W.; Sutherland, B.A. Pericytes and Neurovascular Function in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.F.; Doyeux, V.; Berg, M.; Peyrounette, M.; Haft-Javaherian, M.; Larue, A.E.; Slater, J.H.; Lauwers, F.; Blinder, P.; Tsai, P.; et al. Brain Capillary Networks Across Species: A few Simple Organizational Requirements Are Sufficient to Reproduce Both Structure and Function. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.V.; Bouvier, D.S. Astrocyte-Secreted Matricellular Proteins in CNS Remodelling during Development and Disease. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 321209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, E.H.; Marinelli, N.A.; Shi, Y.; McClatchey, P.M.; Balotin, K.M.; Gullett, D.R.; Hagerla, K.A.; Bowman, A.B.; Ess, K.C.; Wikswo, J.P.; et al. A Simplified, Fully Defined Differentiation Scheme for Producing Blood-Brain Barrier Endothelial Cells from Human iPSCs. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, E.M.; Banks, W.A. Role of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Central Nervous System Insulin Resistance. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucullo, L.; Hossain, M.; Puvenna, V.; Marchi, N.; Janigro, D. The role of shear stress in Blood-Brain Barrier endothelial physiology. BMC Neurosci. 2011, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tellingen, O.; Yetkin-Arik, B.; de Gooijer, M.C.; Wesseling, P.; Wurdinger, T.; de Vries, H.E. Overcoming the blood–brain tumor barrier for effective glioblastoma treatment. Drug Resist. Updates 2015, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, E.M.; Collen, D.; Carmeliet, P. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001, 49, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell-Loftin, M.K.; Bayer, S.V.H.; Crist, E.; Hughes, T.; Joison, S.M.; Longmore, G.D.; George, S.C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts support vascular growth through mechanical force. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahir, B.K.; Engelhard, H.H.; Lakka, S.S. Tumor Development and Angiogenesis in Adult Brain Tumor: Glioblastoma. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2461–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, X. Dual role of WNT5A in promoting endothelial differentiation of glioma stem cells and angiogenesis of glioma derived endothelial cells. Oncogene 2021, 40, 5081–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.D.; Arora, Y.; Mahajan, K. Anatomy, Blood Vessels. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Structure and Function of Blood Vessels. Available online: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-herkimer-biologyofaging/chapter/structure-and-function-of-blood-vessels/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Crapser, J.D.; Ochaba, J.; Soni, N.; Reidling, J.C.; Thompson, L.M.; Green, K.N. Microglial depletion prevents extracellular matrix changes and striatal volume reduction in a model of Huntington’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Pang, L.; Dunterman, M.; Lesniak, M.S.; Heimberger, A.B.; Chen, P. Macrophages and microglia in glioblastoma: Heterogeneity, plasticity, and therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e163446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, B.; Hu, X.; Kim, H.; Squatrito, M.; Scarpace, L.; deCarvalho, A.C.; Lyu, S.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; et al. Tumor Evolution of Glioma-Intrinsic Gene Expression Subtypes Associates with Immunological Changes in the Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 42–56.e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J.H.; Gunn, M.D.; Fecci, P.E.; Ashley, D.M. Brain immunology and immunotherapy in brain tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangoso, E.; Southgate, B.; Bradley, L.; Rus, S.; Galvez-Cancino, F.; McGivern, N.; Guc, E.; Kapourani, C.A.; Byron, A.; Ferguson, K.M.; et al. Glioblastomas acquire myeloid-affiliated transcriptional programs via epigenetic immunoediting to elicit immune evasion. Cell 2021, 184, 2454–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogstrate, Y.; Draaisma, K.; Ghisai, S.A.; van Hijfte, L.; Barin, N.; de Heer, I.; Coppieters, W.; van den Bosch, T.P.P.; Bolleboom, A.; Gao, Z.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals tumor microenvironment changes in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 678–692.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo Antunes, A.R.; Scheyltjens, I.; Duerinck, J.; Neyns, B.; Movahedi, K.; Van Ginderachter, J.A. Understanding the glioblastoma immune microenvironment as basis for the development of new immunotherapeutic strategies. Elife 2020, 9, e52176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Chanoch-Myers, R.; Mathewson, N.D.; Myskiw, C.; Atta, L.; Bussema, L.; Eichhorn, S.W.; Greenwald, A.C.; Kinker, G.S.; Rodman, C.; et al. Interactions between cancer cells and immune cells drive transitions to mesenchymal-like states in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Hawkins, C.; Clarke, I.D.; Squire, J.A.; Bayani, J.; Hide, T.; Henkelman, R.M.; Cusimano, M.D.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 2004, 432, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, N.; Miele, L.; Harris, P.J.; Jeong, W.; Bando, H.; Kahn, M.; Yang, S.X.; Ivy, S.P. Targeting notch, hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah-Pine, F.; Khettab, M.; Bedoui, Y.; Slama, Y.; Daniel, M.; Doray, B.; Gasque, P. On the origin and development of glioblastoma: Multifaceted role of perivascular mesenchymal stromal cells. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathia, J.D.; Mack, S.C.; Mulkearns-Hubert, E.E.; Valentim, C.L.; Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes. Dev. 2015, 29, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vescovi, A.L.; Reynolds, B.A.; Galli, R. Brain tumour stem cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.L.V.; Gomes, I.N.F.; Carloni, A.C.; Rosa, M.N.; da Silva, L.S.; Evangelista, A.F.; Reis, R.M.; Silva, V.A.O. Role of glioblastoma stem cells in cancer therapeutic resistance: A perspective on antineoplastic agents from natural sources and chemical derivatives. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, M.J.; Lembong, J.; Muramoto, S.; Gillen, G.; Fisher, J.P. The Evolution of Polystyrene as a Cell Culture Material. Tissue Eng. Part. B Rev. 2018, 24, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, E.; Antonietti, S.; Ius, T.; Fontanella, M.M.; Zeppieri, M.; Panciani, P.P. Glioma Stem Cells as Promoter of Glioma Progression: A Systematic Review of Molecular Pathways and Targeted Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, V.L.; Valdes, P.A.; Hickey, W.F.; De Leo, J.A. Current review of in vivo GBM rodent models: Emphasis on the CNS-1 tumour model. ASN Neuro 2011, 3, e00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segel, M.; Neumann, B.; Hill, M.F.E.; Weber, I.P.; Viscomi, C.; Zhao, C.; Young, A.; Agley, C.C.; Thompson, A.J.; Gonzalez, G.A.; et al. Niche stiffness underlies the ageing of central nervous system progenitor cells. Nature 2019, 573, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.W.; Williams, D.A.; Watt, F.M. Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhou, W.; Xiang, C.; Huang, H.; Miele, L.; Liu, Z.; Bebek, G.; Bao, S.; et al. Hypoxic Induction of Vasorin Regulates Notch1 Turnover to Maintain Glioma Stem-like Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 104–118.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.J.; Shakya, S.; Barnett, A.; Wallace, L.C.; Jeon, H.; Sloan, A.; Recinos, V.; Hubert, C.G. Three-dimensional organoid culture unveils resistance to clinical therapies in adult and pediatric glioblastoma. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 15, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Y.; Hua, S.; Tanwar, P.S. Extracellular matrix-mediated regulation of cancer stem cells and chemoresistance. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 109, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Z.K.; Lokman, N.A.; Ricciardelli, C. Differing Roles of Hyaluronan Molecular Weight on Cancer Cell Behavior and Chemotherapy Resistance. Cancers 2018, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cescon, M.; Rampazzo, E.; Bresolin, S.; Da Ros, F.; Manfreda, L.; Cani, A.; Della Puppa, A.; Braghetta, P.; Bonaldo, P.; Persano, L. Collagen VI sustains cell stemness and chemotherapy resistance in glioblastoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, T.A.; de Juan Pardo, E.M.; Kumar, S. The Mechanical Rigidity of the Extracellular Matrix Regulates the Structure, Motility, and Proliferation of Glioma Cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4167–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Rengarajan, V.; Kjar, A.; Huang, Y. A matrigel-free method to generate matured human cerebral organoids using 3D-Printed microwell arrays. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, P.C.; Miller, W.J.; Meaney, D.F.; Sawyer, E.S.; Janmey, P.A. Matrices with Compliance Comparable to that of Brain Tissue Select Neuronal over Glial Growth in Mixed Cortical Cultures. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 3012–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-M.; Wang, H.-B.; Dembo, M.; Wang, Y.-l. Cell Movement Is Guided by the Rigidity of the Substrate. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.T.; Harley, B.A.C. Perivascular signals alter global gene expression profile of glioblastoma and response to temozolomide in a gelatin hydrogel. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Gwon, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Therapeutic strategies of three-dimensional stem cell spheroids and organoids for tissue repair and regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achilli, T.-M.; McCalla, S.; Meyer, J.; Tripathi, A.; Morgan, J.R. Multilayer Spheroids To Quantify Drug Uptake and Diffusion in 3D. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Martinez, S.; Lara-Mayorga, I.M.; Samandari, M.; Mendoza-Buenrostro, C.; Flores-Garza, B.G.; Reyes-Cortes, L.M.; Segoviano-Ramirez, J.C.; Zhang, Y.S.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; Alvarez, M.M. Culture of cancer spheroids and evaluation of anti-cancer drugs in 3D-printed miniaturized continuous stirred tank reactors (mCSTRs). Biofabrication 2022, 14, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, H. Methods for inducing embryoid body formation: In vitro differentiation system of embryonic stem cells. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 103, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, J.; Kensah, G.; Kempf, H.; Skvorc, D.; Gawol, A.; Elliott, D.A.; Dräger, G.; Zweigerdt, R.; Martin, U.; Gruh, I. The use of agarose microwells for scalable embryoid body formation and cardiac differentiation of human and murine pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2463–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Park, S.A.; Kim, W.D.; Ha, T.; Xin, Y.Z.; Lee, J.; Lee, D. Current Advances in 3D Bioprinting Technology and Its Applications for Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2020, 12, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermida, M.A.; Kumar, J.D.; Schwarz, D.; Laverty, K.G.; Di Bartolo, A.; Ardron, M.; Bogomolnijs, M.; Clavreul, A.; Brennan, P.M.; Wiegand, U.K.; et al. Three dimensional in vitro models of cancer: Bioprinting multilineage glioblastoma models. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 75, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, M.; Chebath, J.; Margulets, V.; Laevsky, I.; Miropolsky, Y.; Shariki, K.; Peri, M.; Blais, I.; Slutsky, G.; Revel, M.; et al. Suspension Culture of Undifferentiated Human Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2010, 6, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakod, P.S.; Kim, Y.; Rao, S.S. The Impact of Astrocytes and Endothelial Cells on Glioblastoma Stemness Marker Expression in Multicellular Spheroids. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2021, 14, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakod, P.S.; Kondapaneni, R.V.; Edney, B.; Kim, Y.; Rao, S.S. The impact of temozolomide and lonafarnib on the stemness marker expression of glioblastoma cells in multicellular spheroids. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38, e3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, C.; Grundy, T.J.; Strissel, P.L.; Bohringer, D.; Grummel, N.; Gerum, R.; Steinwachs, J.; Hack, C.C.; Beckmann, M.W.; Eckstein, M.; et al. Collective forces of tumor spheroids in three-dimensional biopolymer networks. Elife 2020, 9, e51912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Weisz, A.; Kurashima, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Ogura, T.; D’Acquisto, F.; Addeo, R.; Makuuchi, M.; Esumi, H. Hypoxia response element of the human vascular endothelial growth factor gene mediates transcriptional regulation by nitric oxide: Control of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity by nitric oxide. Blood 2000, 95, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, M.; Box, C.; Eccles, S.A. Three-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroid invasion assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, e52686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Ahn, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, D.; Jeon, N.L. Tumor spheroid-on-a-chip: A standardized microfluidic culture platform for investigating tumor angiogenesis. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 2822–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Hora, C.C.; Schweiger, M.W.; Wurdinger, T.; Tannous, B.A. Patient-Derived Glioma Models: From Patients to Dish to Animals. Cells 2019, 8, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelava, I.; Lancaster, M.A. Dishing out mini-brains: Current progress and future prospects in brain organoid research. Dev. Biol. 2016, 420, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Salinas, R.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Schnoll, J.G.; Wong, S.Z.H.; Thokala, R.; Sheikh, S.; Saxena, D.; Prokop, S.; et al. A Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoid Model and Biobank Recapitulates Inter- and Intra-tumoral Heterogeneity. Cell 2020, 180, 188–204.e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.-A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 2014, 345, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubert, J.; Celotti, M.; Lorenzoni, M.; Beccaceci, G.; Alaimo, A.; Foletto, V.; Fortuna, N.; DeFelice, D.; Andreatta, F.; Genovesi, S. The Organoid Era Permits the Development of New Applications to Study Glioblastoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzarelli, R. Organoid Models of Glioblastoma to Study Brain Tumor Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Repic, M.; Guo, Z.; Kavirayani, A.; Burkard, T.; Bagley, J.A.; Krauditsch, C.; Knoblich, J.A. Genetically engineered cerebral organoids model brain tumor formation. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Jacob, F.; Song, M.M.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, H.; Ming, G.L. Generation of human brain region-specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Announces Plan to Phase Out Animal Testing Requirement for Monoclonal Antibodies and Other Drugs. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-announces-plan-phase-out-animal-testing-requirement-monoclonal-antibodies-and-other-drugs (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Cacciamali, A.; Villa, R.; Dotti, S. 3D Cell Cultures: Evolution of an Ancient Tool for New Applications. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 836480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Parveen, M.; Bala, A.; Sur, D. The 3C (Cell Culture, Computer Simulation, Clinical Trial) Solution for Optimizing the 3R (Replace, Reduction, Refine) Framework during Preclinical Research Involving Laboratory Animals. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 1188–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, B.B.; Sievers, C.; Donohue, L.K.; Gillespie, S.M.; Flavahan, W.A.; Miller, T.E.; Venteicher, A.S.; Hebert, C.H.; Carey, C.D.; Rodig, S.J.; et al. Adaptive Chromatin Remodeling Drives Glioblastoma Stem Cell Plasticity and Drug Tolerance. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 233–246.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Clarke, I.D.; Terasaki, M.; Bonn, V.E.; Hawkins, C.; Squire, J.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of a Cancer Stem Cell in Human Brain Tumors. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5821–5828. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. CD133: A stem cell biomarker and beyond. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, W. Sox2, a key factor in the regulation of pluripotency and neural differentiation. World J. Stem Cells 2014, 6, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvà, M.L.; Rheinbay, E.; Gillespie, S.M.; Patel, A.P.; Wakimoto, H.; Rabkin, S.D.; Riggi, N.; Chi, A.S.; Cahill, D.P.; Nahed, B.V.; et al. Reconstructing and Reprogramming the Tumor-Propagating Potential of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Cell 2014, 157, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posthoorn-Verheul, C.; Fabro, F.; Ntafoulis, I.; den Hollander, C.; Verploegh, I.S.C.; Balvers, R.; Kers, T.V.; Hoogeveen, J.; van der Burg, J.; Eussen, B.; et al. Optimized culturing yields high success rates and preserves molecular heterogeneity, enabling personalized screening for high-grade gliomas. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neftel, C.; Laffy, J.; Filbin, M.G.; Hara, T.; Shore, M.E.; Rahme, G.J.; Richman, A.R.; Silverbush, D.; Shaw, M.L.; Hebert, C.M.; et al. An Integrative Model of Cellular States, Plasticity, and Genetics for Glioblastoma. Cell 2019, 178, 835–849.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, J.; Pao, G.M.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Verma, I.M. Glioblastoma Model Using Human Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, A.C.; Picard, D.; Qin, N.; Wolter, M.; Kaulich, K.; Hewera, M.; Pauck, D.; Marquardt, V.; Torga, G.; Muhammad, S.; et al. Longitudinal stability of molecular alterations and drug response profiles in tumor spheroid cell lines enables reproducible analyses. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.A.; Mullins, R.D. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 2010, 463, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, V.; Smith, J.; Sandor, C.; Ried, J.S.; Baud, A.; Handel, A.; Newey, S.E.; Wessely, F.; Attar, M.; Whiteley, E.; et al. Reproducibility of Molecular Phenotypes after Long-Term Differentiation to Human iPSC-Derived Neurons: A Multi-Site Omics Study. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 11, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Weick, J.P.; Yu, J.; Ma, L.X.; Zhang, X.Q.; Thomson, J.A.; Zhang, S.C. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4335–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozhei, O.; Teschemacher, A.G.; Kasparov, S. Viral Vectors as Gene Therapy Agents for Treatment of Glioblastoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstung, M.; Jolly, C.; Leshchiner, I.; Dentro, S.C.; Gonzalez, S.; Rosebrock, D.; Mitchell, T.J.; Rubanova, Y.; Anur, P.; Yu, K.; et al. The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature 2020, 578, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.M.; Ikeda, K.; Cromer, M.K.; Uchida, N.; Nishimura, T.; Romano, R.; Tong, A.J.; Lemgart, V.T.; Camarena, J.; Pavel-Dinu, M.; et al. Highly Efficient and Marker-free Genome Editing of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by CRISPR-Cas9 RNP and AAV6 Donor-Mediated Homologous Recombination. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 821–828.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Mooney, D.J. Chemical strategies to engineer hydrogels for cell culture. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.S.; Postovit, L.M.; Lajoie, G.A. Matrigel: A complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics 2010, 10, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliari, S.R.; Burdick, J.A. A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenbrey, E.A.; Murphy, W.L. Synthetic alternatives to Matrigel. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tibbitt, M.W.; Basta, L.; Anseth, K.S. Mechanical memory and dosing influence stem cell fate. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlits, S.K.; Khaing, Z.Z.; Petersen, R.R.; Nickels, J.D.; Vanscoy, J.E.; Shear, J.B.; Schmidt, C.E. The effects of hyaluronic acid hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties on neural progenitor cell differentiation. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3930–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; Chinzei, K.; Orssengo, G.; Bednarz, P. Mechanical properties of brain tissue in-vivo: Experiment and computer simulation. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budday, S.; Sommer, G.; Birkl, C.; Langkammer, C.; Haybaeck, J.; Kohnert, J.; Bauer, M.; Paulsen, F.; Steinmann, P.; Kuhl, E.; et al. Mechanical characterization of human brain tissue. Acta Biomater. 2017, 48, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tong, X.; Yang, F. Bioengineered 3D Brain Tumor Model To Elucidate the Effects of Matrix Stiffness on Glioblastoma Cell Behavior Using PEG-Based Hydrogels. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthanarayanan, B.; Kim, Y.; Kumar, S. Elucidating the mechanobiology of malignant brain tumors using a brain matrix-mimetic hyaluronic acid hydrogel platform. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7913–7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miroshnikova, Y.A.; Mouw, J.K.; Barnes, J.M.; Pickup, M.W.; Lakins, J.N.; Kim, Y.; Lobo, K.; Persson, A.I.; Reis, G.F.; McKnight, T.R.; et al. Tissue mechanics promote IDH1-dependent HIF1α–tenascin C feedback to regulate glioblastoma aggression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, U.; Ford, E.M.; Ha, B.; Rijns, L.; Chaudhuri, O.; Dankers, P.Y.W.; Kloxin, A.M.; Snedeker, J.G.; Gentleman, E. Engineered hydrogels for mechanobiology. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M.R. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: An overview. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Tiwari, S.K.; Agrawal, K.; Tan, M.T.; Dang, J.S.; Tam, T.; Tian, J.; Wan, X.Y.; Schimelman, J.; You, S.T.; et al. Rapid 3D Bioprinting of Glioblastoma Model Mimicking Native Biophysical Heterogeneity. Small 2021, 17, 2006050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, S.; Jayarajan, V.; Wray, S.; Kamm, R.; Moeendarbary, E. Mechanobiology of the blood-brain barrier during development, disease and ageing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, M.J.F.; Bell, J.C.; Singaravelu, R. Concise Review: Targeting Cancer Stem Cells and Their Supporting Niche Using Oncolytic Viruses. Stem Cells 2019, 37, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Hsieh, I.Y.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, W. Glioblastoma Stem-Like Cells: Characteristics, Microenvironment, and Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Coskun, A.U.; Jonas, M.; Edelman, E.R.; Feldman, C.L.; Stone, P.H. Role of Endothelial Shear Stress in the Natural History of Coronary Atherosclerosis and Vascular Remodeling: Molecular, Cellular, and Vascular Behavior. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontoura, J.C.; Viezzer, C.; Dos Santos, F.G.; Ligabue, R.A.; Weinlich, R.; Puga, R.D.; Antonow, D.; Severino, P.; Bonorino, C. Comparison of 2D and 3D cell culture models for cell growth, gene expression and drug resistance. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 107, 110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E.; Clark, C.; Sivakumar, H.; Yoo, K.; Aleman, J.; Rajan, S.A.P.; Forsythe, S.; Mazzocchi, A.; Laxton, A.W.; Tatter, S.B.; et al. Immersion Bioprinting of Tumor Organoids in Multi-Well Plates for Increasing Chemotherapy Screening Throughput. Micromachines 2020, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecasis, B.; Aguiar, T.; Arnault, É.; Costa, R.; Gomes-Alves, P.; Aspegren, A.; Serra, M.; Alves, P.M. Expansion of 3D human induced pluripotent stem cell aggregates in bioreactors: Bioprocess intensification and scaling-up approaches. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 246, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Y.; Vermette, P. Bioreactors for tissue mass culture: Design, characterization, and recent advances. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7481–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, J.; Birch, J. Reactor design for large scale suspension animal cell culture. Cytotechnology 1999, 29, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, J.I.; Baganz, F. Miniature bioreactors: Current practices and future opportunities. Microb. Cell Factories 2006, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avena, P.; Zavaglia, L.; Casaburi, I.; Pezzi, V. Perfusion Bioreactor Technology for Organoid and Tissue Culture: A Mini Review. Onco 2025, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienow, A.W. Reactor engineering in large scale animal cell culture. Cytotechnology 2006, 50, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Robinson, D.K. Industrial choices for protein production by large-scale cell culture. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001, 12, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Kempf, H.; Hetzel, M.; Hesse, C.; Hashtchin, A.R.; Brinkert, K.; Schott, J.W.; Haake, K.; Kuhnel, M.P.; Glage, S.; et al. Bioreactor-based mass production of human iPSC-derived macrophages enables immunotherapies against bacterial airway infections. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.; Kimmel, H.; Rondo, E.; Underhill, G.H. Advances in high throughput cell culture technologies for therapeutic screening and biological discovery applications. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 9, e10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Park, C.-H.; Choi, D.-H.; Hong, J.K.; Lee, D.-Y. Bioprocess digital twins of mammalian cell culture for advanced biomanufacturing. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 33, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, A.; Carvell, J.; Butler, M. Applications of bio-capacitance to cell culture manufacturing. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 61, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. NIH Establishes Nation’s First Dedicated Organoid Development Center to Reduce Reliance on Animal Modeling. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-establishes-nations-first-dedicated-organoid-development-center-reduce-reliance-animal-modeling (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. NIH Standardized Organoid Modeling (SOM) Center. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/som (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Whaley, D.; Damyar, K.; Witek, R.P.; Mendoza, A.; Alexander, M.; Lakey, J.R. Cryopreservation: An Overview of Principles and Cell-Specific Considerations. Cell Transplant. 2021, 30, 0963689721999617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Wetering, M.; Francies, H.E.; Francis, J.M.; Bounova, G.; Iorio, F.; Pronk, A.; van Houdt, W.; van Gorp, J.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Kester, L.; et al. Prospective Derivation of a Living Organoid Biobank of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cell 2015, 161, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfaghar, M.; Acharya, P.; Joshi, P.; Choi, N.Y.; Shrestha, S.; Lekkala, V.K.R.; Kang, S.Y.; Lee, M.; Lee, M.Y. Cryopreservation of Neuroectoderm on a Pillar Plate and In Situ Differentiation into Human Brain Organoids. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7111–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.S.; Hinman, S.S.; Kim, R.; Wang, Y.; Allbritton, N.L. Primary Cell-Derived Intestinal Models: Recapitulating Physiology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjorevski, N.; Nikolaev, M.; Brown, T.E.; Mitrofanova, O.; Brandenberg, N.; DelRio, F.W.; Yavitt, F.M.; Liberali, P.; Anseth, K.S.; Lutolf, M.P. Tissue geometry drives deterministic organoid patterning. Science 2022, 375, eaaw9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, M.; Mitrofanova, O.; Broguiere, N.; Geraldo, S.; Dutta, D.; Tabata, Y.; Elci, B.; Brandenberg, N.; Kolotuev, I.; Gjorevski, N.; et al. Homeostatic mini-intestines through scaffold-guided organoid morphogenesis. Nature 2020, 585, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, M.; Chang, C.; Fan, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, G. Caliber of Intracranial Arteries as a Marker for Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 558858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bouri, W.K.; Payne, S.J. A statistical model of the penetrating arterioles and venules in the human cerebral cortex. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrounette, M.; Davit, Y.; Quintard, M.; Lorthois, S. Multiscale modelling of blood flow in cerebral microcirculation: Details at capillary scale control accuracy at the level of the cortex. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Miner, A.; Hennis, L.; Mittal, S. Mechanisms of temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma—A comprehensive review. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, H.; Sanford, K.; Szwedo, P.K.; Pathak, R.; Ghosh, A. Synthetic Matrices for Intestinal Organoid Culture: Implications for Better Performance. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.C.; Costa, E.C.; Filipe, H.A.L.; Saraiva, S.M.; Jacinto, T.; Miguel, S.P.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Coutinho, P. Animal-derived products in science and current alternatives. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 151, 213428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioreactor Type | Bioreactor Geometry | Range of Shear (τ, Pa) | Uniformity of Shear | Working Volume Scalability (Scale Up or Out) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates | Static 2D surface (multi-well plates) | Negligible (~0 Pa) | N/A | Very low ≤2 mL (Scale out) | [176,177] |

| Stirred tank | Cylindrical | Low to moderate (<0.5 Pa) | Moderate. Highest shear is concentrated near the impeller or stirring element. | High, 50 mL to 1000–25,000 L (Scale up) | [117,139,178,179,180,181] |

| Rotating wall | Concentric | Very low and controlled (<0.01 Pa) | High. Homogenous shear distribution across the fluid volume due to constant rotation. | Medium, up to 500 mL (Scale out) | [180,182] |

| Perfusion | Hollow fiber/cartridge | Low to moderate (<0.1 Pa) | High. Designed for laminar flow. | Medium, up to 500 mL (Scale out) | [12,183] |

| Wave/shaking | Rectangular | Low to moderate pulsatile | Moderate to Low. Non-uniform; highest at the liquid-air interface due to wave direction. | Medium, 1 mL to 100 L (Scale out) | [182,184,185] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avera, A.D.; Kim, Y. Bioengineering Stem Cell-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121830

Avera AD, Kim Y. Bioengineering Stem Cell-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121830

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvera, Alexandra D., and Yonghyun Kim. 2025. "Bioengineering Stem Cell-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids: A Comprehensive Review" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121830

APA StyleAvera, A. D., & Kim, Y. (2025). Bioengineering Stem Cell-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121830