Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Outcome

2.2. VDR Expression

2.3. Mucosal Microbiota Composition

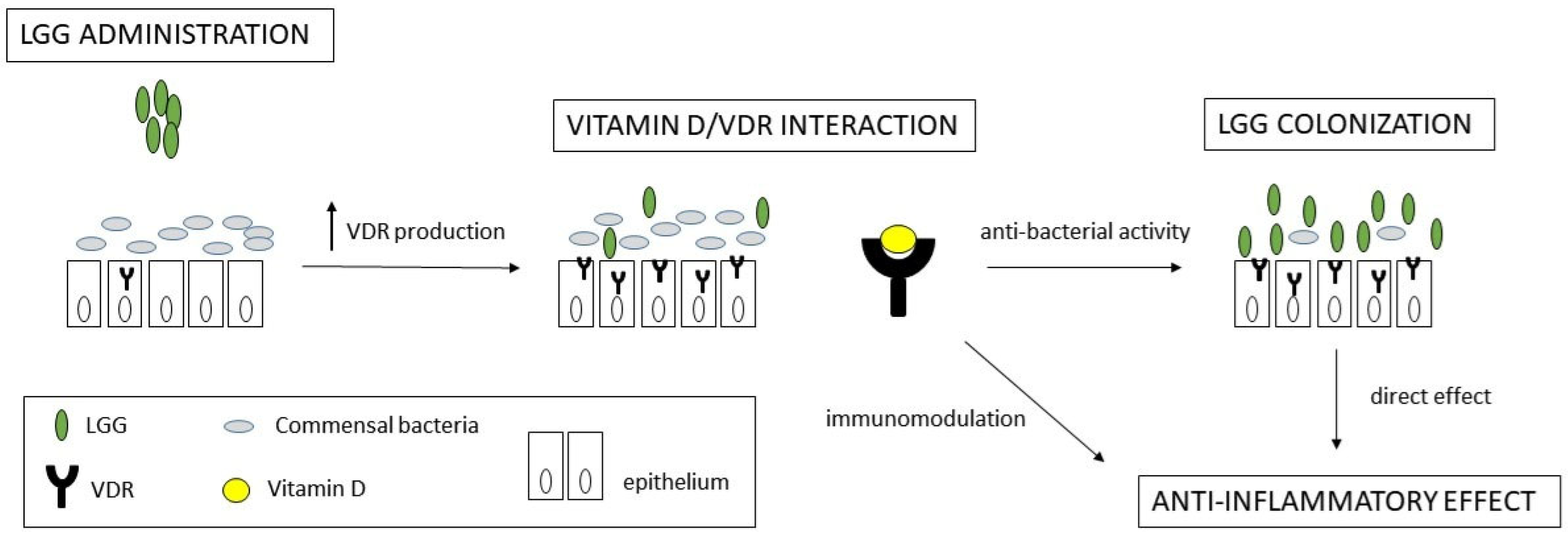

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Bioptic Samples

4.2. DNA Extraction from Human Biopsies

4.3. Gene Expression Analysis

4.4. Immunohistochemistry on Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Sections

4.5. Determination of Bacterial Profiles by Amplicon Sequencing

4.6. Data Processing and Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iliev, I.D.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Guo, C.-J. Microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: Mechanisms of disease and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, C.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2023, 402, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, L.; Gordon, M.; Baines, P.A.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Sinopoulou, V.; Akobeng, A.K. Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 3, CD005573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Kaur, L.; Gordon, M.; Baines, P.A.; Sinopoulou, V.; Akobeng, A.K. Probiotics for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 3, CD007443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, L. Thirty Years of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: A Review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53 (Suppl. S1), S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zocco, M.A.; dal Verme, L.Z.; Cremonini, F.; Piscaglia, A.C.; Nista, E.C.; Candelli, M.; Novi, M.; Rigante, D.; Cazzato, I.A.; Ojetti, V.; et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 23, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Di Paolo, M.C.; Urgesi, R.; Pallotta, L.; Fanello, G.; Graziani, M.G.; Fave, G.D. Safety and Potential Role of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration as Monotherapy in Ulcerative Colitis Patients with Mild-Moderate Clinical Activity. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankainen, M.; Paulin, L.; Tynkkynen, S.; von Ossowski, I.; Reunanen, J.; Partanen, P.; Satokari, R.; Vesterlund, S.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; Lebeer, S.; et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reveals pili containing a human- mucus binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17193–17198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, K.A.; Gareau, M.G.; Wang, Y.J.J.; Sherman, P.M. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced barrier dysfunction and pro-inflammatory signalling. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3288–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Cao, H.; Cover, T.L.; Washington, M.K.; Shi, Y.; Liu, L.; Chaturvedi, R.; Peek, R.M.; Wilson, K.T.; Polk, D.B. Colon-specific delivery of a probiotic-derived soluble protein ameliorates intestinal inflammation in mice through an EGFR-dependent mechanism. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2242–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Corleto, V.D.; Martorelli, M.; Lanini, C.; D’ambra, G.; Di Giulio, E.; Fave, G.D. Mucosal adhesion and anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the human colonic mucosa: A proof-of-concept study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4652–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mei, L.; Hao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ji, Y. Contemporary Perspectives on the Role of Vitamin D in Enhancing Gut Health and Its Implications for Preventing and Managing Intestinal Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pinto, R.; Ferri, C.; Cominelli, F. Vitamin D Axis in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Role, Current Uses and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Di Paolo, M.C.; Graziani, M.G.; Fave, G.D. Probiotics and Vitamin D/Vitamin D Receptor Pathway Interaction: Potential Therapeutic Implications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 747856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yoon, S.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Lu, R.; Xia, Y.; Wan, J.; Petrof, E.O.; Claud, E.C.; Chen, D.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor pathway is required for probiotic protection in colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 309, G341–G349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, C.B.; Cruz, M.L.; Isidro, A.A.; Arthur, J.C.; Jobin, C.; De Simone, C. Pretreatment with the probiotic VSL#3 delays transition from inflammation to dysplasia in a rat model of colitis-associated cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G1004–G1013. [Google Scholar]

- Mencarelli, A.; Cipriani, S.; Renga, B.; Bruno, A.; D'Amore, C.; Distrutti, E.; Fiorucci, S. VSL#3 resets insulin signaling and protects against NASH and atherosclerosis in a model of genetic dyslipidemia and intestinal inflammation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45425. [Google Scholar]

- Raveschot, C.; Coutte, F.; Frémont, M.; Vaeremans, M.; Dugersuren, J.; Demberel, S.; Drider, D.; Dhulster, P.; Flahaut, C.; Cudennec, B. Probiotic Lactobacillus strains from Mongolia improve calcium transport and uptake by intestinal cells in vitro. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, G.; Pei, Z.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhao, J.; Lu, S.; Lu, W. Bifidobacterium longum increases serum vitamin D metabolite levels and modulates intestinal flora to alleviate osteoporosis in mice. mSphere 2025, 10, e0103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.H. Emerging Roles of Vitamin D-Induced Antimicrobial Peptides in Antiviral Innate Immunity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leser, T.; Baker, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, LGG® Probiotic Function. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazul, H.; Kanda, L.L.; Gondek, D. Impact of probiotic supplements on microbiome diversity following antibiotic treatment of mice. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Rawat, A.; Alwakeel, M.; Sharif, E.; Al Khodor, S. The potential role of vitamin D supplementation as a gut microbiota modifier in healthy individuals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmora, N.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Bashiardes, S.; Kotler, E.; Zur, M.; Regev-Lehavi, D.; Brik, R.B.-Z.; et al. Personalized Gut Mucosal Colonization Resistance to Empiric Probiotics Is Associated with Unique Host and Microbiome Features. Cell 2018, 174, 1388–1405.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, I.; Sundin, J.; Fuentes, S.; Repsilber, D.; de Vos, W.M.; Brummer, R.J. The relationship between faecal-associated and mucosal-associated microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uronis, J.M.; Arthur, J.C.; Keku, T.; Fodor, A.; Carroll, I.M.; Cruz, M.L.; Appleyard, C.B.; Jobin, C. Gut microbial diversity is reduced by the probiotic VSL#3 and correlates with decreased TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini, C.; Saeed, R.; Bamias, G.; Arseneau, K.O.; Pizarro, T.T.; Cominelli, F. Probiotics promote gut health through stimulation of epithelial innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, RESEARCH0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masella, A.P.; Bartram, A.K.; Truszkowski, J.M.; Brown, D.G.; Neufeld, J.D. PANDAseq: Paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Beiko, R.G. 16S rRNA Gene Analysis with QIIME2. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1849, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Original Study (n = 76) | Present Study (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 57 ± 15 | 53 ± 16 |

| Gender (M/F) | 37/39 | 7/6 |

| Disease duration (yrs) | 9.6 ± 7.1 | 7.2 ± 5.4 |

| Extension: | ||

| Proctitis Proctosigmoiditis Pancolitis | 12 (16%) 41 (54%) 23 (30%) | 4 (31%) 7 (54%) 2 (15%) |

| Partial Mayo: | ||

| 2 3 4 | 62 (82%) 10 (13%) 4 (5%) | 11 (85%) 2 (15%) 0 |

| LGG dose: | ||

| Regular Double | 38 (51%) 37 (49%) | 7 (54%) 6 (46%) |

| Clinical outcome *: | ||

| Response Stable Flare | 32/52 (58%) 21/52 (38%) 2/52 (2%) | 6 (46%) 7 (54%) 0 |

| Endoscopic outcome **: | ||

| Response Stable Worse | 7/27 (26%) 19/27 (70%) 1/27 (4%) | 3 (23%) 9 (69%) 1 (8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagnini, C.; Gori, M.; Di Paolo, M.C.; Urgesi, R.; Cicione, C.; Zingariello, M.; Arciprete, F.; Velardi, V.; Viciani, E.; Padella, A.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111651

Pagnini C, Gori M, Di Paolo MC, Urgesi R, Cicione C, Zingariello M, Arciprete F, Velardi V, Viciani E, Padella A, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111651

Chicago/Turabian StylePagnini, Cristiano, Manuele Gori, Maria Carla Di Paolo, Riccardo Urgesi, Claudia Cicione, Maria Zingariello, Francesca Arciprete, Viola Velardi, Elisa Viciani, Antonella Padella, and et al. 2025. "Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111651

APA StylePagnini, C., Gori, M., Di Paolo, M. C., Urgesi, R., Cicione, C., Zingariello, M., Arciprete, F., Velardi, V., Viciani, E., Padella, A., Castagnetti, A., Graziani, M. G., & Delle Fave, G. (2025). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111651