Abstract

Solanum surattense Burm. f. is a significant member of the Solanaceae family, and the Solanum genus is renowned for its traditional medicinal uses and bioactive potential. This systematic review adheres to PRISMA methodology, analyzing scientific publications between 1753 and 2023 from B-on, Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Web of Science, aiming to provide comprehensive and updated information on the distribution, ethnomedicinal uses, chemical constituents, and pharmacological activities of S. surattense, highlighting its potential as a source of herbal drugs. Ethnomedicinally, this species is important to treat skin diseases, piles complications, and toothache. The fruit was found to be the most used part of this plant (25%), together with the whole plant (22%) used to treat different ailments, and its decoction was found to be the most preferable mode of herbal drug preparation. A total of 338 metabolites of various chemical classes were isolated from S. surattense, including 137 (40.53%) terpenoids, 56 (16.56%) phenol derivatives, and 52 (15.38%) lipids. Mixtures of different parts of this plant in water–ethanol have shown in vitro and/or in vivo antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-tumoral, hepatoprotective, and larvicidal activities. Among the metabolites, 51 were identified and biologically tested, presenting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumoral as the most reported activities. Clinical trials in humans made with the whole plant extract showed its efficacy as an anti-asthmatic agent. Mostly steroidal alkaloids and triterpenoids, such as solamargine, solanidine, solasodine, solasonine, tomatidine, xanthosaponin A–B, dioscin, lupeol, and stigmasterol are biologically the most active metabolites with high potency that reflects the new and high potential of this species as a novel source of herbal medicines. More experimental studies and a deeper understanding of this plant must be conducted to ensure its use as a source of raw materials for pharmaceutical use.

1. Introduction

Solanum surattense Burm. f. is an important species of the Nightshade family Solanaceae and genus Solanum L., which is the most representative and largest genus comprising 1235 accepted species [1].

There was a debate in the past concerning the Solanum surattense species name, after which this species was named Solanum virginianum L. by Linnaeus (1753) [2]. After that, Burmanii (1768) described it and named it S. surattense [3], and S. surattense by Scharder and Wendland (1795) [4] based on S. virginianum. It has 16 synonyms, but among them, S. surattense was mostly used as a synonym [5,6,7]. However, S. surattense is now stated as the legitimate taxonomic name [8], and S. virginianum is used as the basionym of this species. This species is known by different local names in different countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of synonyms and local names of Solanum surattense [1,9,10,11].

S. surattense is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical parts of Southeast Asia [12]. It is a very common species in Bangladesh and spread all over the country [9]. Morphologically, this species is a prickly, diffuse, perennial herb with procumbent branches, bearing numerous, compressed, straight, and bright yellow prickles (Figure 1). The leaf is very prickly, deeply pinnately lobed with a sinuous outline to the lobes, and very unequal at the base. The flowers are pentamerous, prickly, and purple to bluish-purple. The fruit is a spherical berry, white with green marking when young but light yellow or whitish when ripe [9,13]. The preferable habitat of this species is dry, sunny places, wastelands, along roadsides, and degraded forest areas.

Figure 1.

General picture of S. surattense.

S. surattense is a significant Solanum species reported for its medicinal properties. In accordance, S. surattense is described as being used in traditional medicine in various Oriental regions for treating different ailments. In India and Pakistan, it is commonly used for addressing respiratory issues such as asthma and cough, skin diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, and urinary problems. Its fruit, root, and whole plant are primarily used for the treatment of these health problems, in the form of decoctions, powders, oral and topical administration, and topical semi-solid formulations such as pastes.

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-tumoral, hepatoprotective, and larvicidal biological activities, were demonstrated to different S. surattense plant parts traditional herbal preparations through both in vitro and/or in vivo assays and the marker secondary metabolites responsible or involved in some of these activities identified. Two clinical trials made in humans have confirmed the usefulness of this plant species as an anti-asthmatic agent, reinforcing its potential for therapeutic applications.

Although some of the literature reviews have already been published [14,15,16,17,18] on S. surattense, there are compelling reasons supporting the work hereby presented:

- -

- Reviewing the current scientific research on the species and evaluate the extent of the knowledge that has been published in a broad range of reputable scientific databases;

- -

- Representing the ethnomedicinal potential of Solanum surattense and validating the knowledge scientifically;

- -

- Highlight the identification, characterization, and potentialities of isolated secondary metabolites in terms of drug discovery and development;

- -

- Documentation of more up-to-date information concerning the pharmacological effects of the species. Conclusively, by analyzing the gaps in prior research, providing a detailed account of the species’ ethnomedicinal uses, chemical constituents, and pharmacological properties. This will enable researchers and medical professionals to have access to the most recent scientific evidence, facilitating the development of new herbal medications and promoting the safe and effective use of these traditional medicinal plants.

Scientific data for this review were meticulously collected from several reputable databases, including B-on, Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Web of Science. The search spanned all scientific publications published between 1753 and 2023. The specific thesaurus terms used in the search were “Solanum surattense”, “Solanum xanthocarpum”, “ethnomedicinal value”, “traditional use”, “phytochemical analysis”, and “pharmacological activity”.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Selection of the Information

The procedure to collect and select the data is depicted in Figure 2. From the initial 3661 scientific publications, after removing the duplicates and irrelevant and incomplete results, a total of 231 publications were selected and considered in this review.

Figure 2.

Screening of published data based on the PRISMA methodology.

2.2. Ethnomedicinal Uses

Different parts of S. surattense are utilized in traditional medicine, with the fruit (25%) being the most used part, followed by the whole plant (22%), root (21%), leaf (13%), seed (10%), plant parts mixture (combination) (5%), and flower (4%) (Figure 3). The predominant mode of usage is through decoction. A summary of the traditional uses of S. surattense in medicine is provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material.

Figure 3.

Ethnomedicinal uses of different parts of the S. surattense plant. Abbreviation: Wp—whole plant; L—leaf; F—fruit; S—seed; Fl—flower; R—root.

The use of Solanum surattense in traditional medicine spans seven countries, with India and Pakistan being the primary users. Various parts of this plant are employed to treat multiple ailments [19,20,21].

Numerous reports [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] document the use of the whole plant in India, Iran, Nepal, and Pakistan. It is administered in various forms such as boiled, decoction, juice, paste, powder, topical application, cooked vegetable, and oral administration to address conditions like abdominal pain, arthritis, asthma, cough, colic pain, chronic constipation, fever, hemorrhoids, headache, inflammation, jaundice, leprosy, menstrual problems, paleness, skin issues, stomachache, throat diseases, vaginal infection, and urinary tract problems.

Several studies [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] highlight the medicinal use of S. surattense leaf in China, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. These include topical paste for alopecia, oral infusion and smoke inhalation for asthma and cough, decoction for colds and dental issues, powder with jaggery for genital prolapse, marination with hot mustard oil or juice with Piper nigrum seed powder for joint pain, juice with black pepper and honey for respiratory diseases, and tincture and decoction for respiratory and urinary disorders.

In India and Pakistan, the flowers are commonly fried or powdered and mixed with honey to relieve asthma and cough. Additionally, a paste made from flowers and egg white is used in massages to alleviate arthritis [30,46,59,60].

The fruit is a significant part of the plant used in traditional medicine across Bangladesh, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan [21,27,36,45,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. It is used in various forms such as oral maceration for tumors and swelling, dried chewed fruit for toothache, topical paste for skin lesions, oral juice for diabetes and sore throat, ear drops for earache, decoction for joint pain and respiratory issues, and paste mixed with oil for massage to treat fever and paralysis.

Several articles [33,36,49,55,67,75,78,81,82,83,84,85] describe the use of seeds to treat amenorrhea, cardiac disease, dysmenorrhea, gastrointestinal problems, malaria, migraine, obesity, stomach pain, and toothache in forms such as decoction, rinsing solution, paste, vapor, and powder. In Pakistan, a decoction of the stem with black pepper and salt is orally administered for indigestion, fever, cough, and asthma [86]. Additionally, the root is traditionally used for a wide range of ailments, including abdominal pain, arthritis, asthma, cough, diabetes, fever, headache, hemorrhoids, inflammatory diseases, intestinal infection, jaundice, kidney problems, leprosy, measles, menstrual disorders, nervous system disorders, pain, phlegmatic cough, smallpox, snake bite, toothache, urinary troubles, and weakness through decoction, powder, smoke or fumigation, juice, paste, or tablet [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101].

This species is also used in admixtures with other medicinal plants as polyherbal formulations (Pf) like the nine polyherbal formulations mentioned in Table 2. In Pf1, 4 g of mixed powder is given twice a day with water to treat urinary tract problems; in Pf2, 4 g (one teaspoonful) of mixed powder is given twice a day (morning and bedtime) with water for treating asthma/bronchitis; in Pf3, 4 g of mixed powder is given twice daily (morning and evening, 1 h before meals) with ginger juice for arthritis and rheumatic problems; in Pf4, 3 g of mixed powder is given twice daily (morning and at night before going to bed) with lukewarm water mixed with honey to cure colds; and in Pf5, 4 gm of mixed powder is given twice daily, morning and at bedtime with honey to treat throat diseases [24]. In Pf6, 10 mL of this mixture is given thrice a day for 20–30 days used for cough, fever, jaundice, bronchitis, and diabetes [91]. In Pf7, a mixture of S. surattense root (½ kg) and Saccharum bengalense root (½ kg) were orally administered (decoction) for 8–10 days for intestinal worm problems [71]. In Pf8, a paste of S. surattense root with black pepper (10 g) and ajwain (10 g) is given once a day for 3 days to decrease fever [98]. In the Indian pharmacopeia, Dasamula (Pf9) is used for different ailments like arthritis, asthma, Parkinson’s disease, gout, backache, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant properties, painful, inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders like osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis [102]. In another study, it was mentioned that an equal amount of S. surattense leaf and flower with Leucas linifolia leaf and flower are ground together, warmed, and applied to the swellings of joints for quick recovery [103].

Table 2.

A list polyherbal formulation that includes S. surattense.

2.3. Phytochemistry

Many researchers studied and published information on the chemical constituents of S. surattense in their scientific reports. In the methanol and ethanol extracts of S. surattense whole plant, the presence of steroidal alkaloids, steroidal saponins, methyl esters, phenolic acids, and fatty acids was observed [104,105].

A total of 338 phytochemical constituents of various chemical classes were isolated from S. surattense [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142]. The representative examples of the main compounds are presented in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 and the total identified compounds are represented in Table S2 of the Supplementary Material.

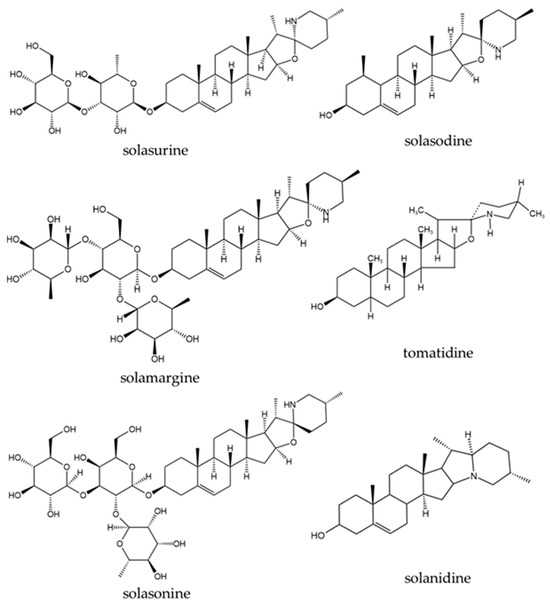

Figure 4.

Examples of phenolic compounds isolated from different parts of S. surattense.

Figure 5.

Examples of steroidal alkaloids isolated from different parts of S. surattense.

Figure 6.

Triterpenoids isolated from different parts of S. surattense.

Figure 7.

Some fatty acids isolated from different parts of S. surattense.

Phenolics: 56 phenolic compounds (16.56%), including phenolic amides (1–8), phenolic acids (9–18), phenolic aldehydes (19), phenolic glycosides (20–22), flavonoids (23–39), coumarins (40–43), anthraquinones (44), lignans (45–55), and tannins (56) were found. These compounds were isolated from different parts of S. surattense (e.g., leaf, stem, fruit, and root) using polar solvents such as water, ethanol, methanol, and hydroethanolic mixtures [104,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119]:

- Phenolic amides such as N-trans-feruloyl tyramine (1) and N-p-trans-coumaroyl tyramine (2) were identified in the whole plant of S. surattense. The compound 2-propenamide, N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-(3) was identified from the absolute alcohol extract of S. surattense leaf. Additionally, compounds such as dihydro-N-feruloyltyramine, N-trans-coumaroyltyramine, N-trans-coumaroyloctopamine, N-[2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl]-3-(4-ethoxyphenyl)-prop-2-enamide, and 3-(4-hydroxy)-N-[2-(3-methoxyphenyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-hydroxy] (4–8) were identified from ethanolic extracts of the fruit part [7,8,12];

- Phenolic acids such as ferulic acid (9) were found in the methanolic extract of the whole plant [104], and evofolin B (10) was also recorded from the same plant part [106]. Chlorogenic acid (11) was isolated from methanolic extracts of the leaf, fruit, stem bark, and root [110,111]. Caffeic acid (12) was extracted from the methanol extract of aerial parts [112]. Compounds such as (1R,3R,4R,5R)-(-)-quinic acid (13) and 2-octylcyclopropene-1-heptanol (14) were recorded from ethanol and methanol extracts of the leaf [107,113]. Eugenol (15) was recorded from hydro-distilled oil extracts of the leaf and fruit, while methyl eugenol (16) and (E)-isoeugenol (17) were identified only from the fruit [114]. Butanedioic acid (18) was found in the ethanolic extract of the fruit part [115];

- Vanillin (19), a phenolic aldehyde, was identified in the ethanolic extract of S. surattense leaf, stem, and fruit, though it was found in significant amounts in the root. Some phenolic glycosides, including chlorogenic acid ethyl ester-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (20), chlorogenic acid methyl ester-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (21), and p-hydroxyphenyl acetonitrile-O-(6′-O-acetyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (22), were identified from the ethanolic extract of S. surattense fruit [109];

- The flavonoid apigenin (23) was isolated from the methanolic extract of various plant parts, including leaf, fruit, petals, stem, and root. Other compounds such as isoquercitrin (24), gallocatechin (25), catechin (26), quercetin (27), flavone (28), luteolin (29), 4H-1-benzopyran-4-one, 5,7-dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxy-(30), 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone (31), 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-6-methoxyflavone (32), 5-hydroxy-8-methoxy-6,7-methylenedioxyflavone (33), 7-hydroxy-6-methoxycoumarin (34), fraxetin (35), 5-hydroxy-6,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (36), 5-hydroxy-4′,6,7-trimethoxyflavone (37), and 5,3′-dihydroxy-6,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone (38) were identified from fruit parts using different solvents such as methanol (70%, 50%, and 30%), ethanol (95%), and aqueous ethanolic solutions [108,115,117,118]. Acetovanillone (39) was found only in the ethanolic extract of the fruit [115];

- Coumarins, including scopoline (40), scopoletin (41), esculin (42), and esculetin (43), were identified from petroleum ether and chloroform extracts of the leaf, fruit, and root parts [119]. The anthraquinone emodin (44) was extracted from the 50% ethanolic extract of the leaf, stem, and root parts;

- The lignans, including threo-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-{4-[(E)-3-hydroxy-1-propenyl]-2-methoxyphenoxy}-1,3-propanediol (45), syringaresinol (46), coniferol (47), simulanol (48), balanophonin (49), glycosmisic acid (50), and tribulusamide A (51), were isolated from the whole plant of S. surattense [106]. Additionally, other lignans such as (7R,8S)-threo-glehlinoside C (52), 2Z-(7S,8R)-aegineoside (53), (7R,8R)-3,5-dimethoxy-8′-carboxy-7′-en-3′,8-epoxy-7,4′-oxyneolignan-4,9-diol (54), and glycerol α-guiacyl ether (55) were identified from the ethanolic extract of the fruit [109,115]. Only one tannin compound, quinic acid (56), was characterized from the ethanolic extract of the fruit [115].

A total of 12.50% of phenolic compounds were found to be biologically active. Among them, 3-(4-hydroxy)-N-[2-(3-methoxyphenyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-hydroxy] (8), p-hydroxyphenyl acetonitrile-O-(6′-O-acetyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside (22), (7R,8S)-threo-glehlinoside C (52), 2Z-(7S,8R)-aegineoside (53), and (7R,8R)-3,5-dimethoxy-8′-carboxy-7′-en-3′,8-epoxy-7,4′-oxyneolignan-4,9-diol (54) showed significant anti-inflammatory activity in vitro. Additionally, caffeic acid (11) and tribulusamide A (51) demonstrated neuroprotective activity in vivo and hepatoprotective activity in vitro, respectively.

Alkaloids: Twenty-one alkaloid compounds (6.21%) were identified, including quinoline alkaloids and steroidal alkaloids [104,105,110,115,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131].

- Quinoline alkaloids, isoquinoline (57) was isolated from the ethanolic extract of S. surattense fruit [115].

- Twenty steroidal alkaloids (58–77) have been reported from S. surattense [104,105,110,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131]. Among them, compounds (58–64) were isolated from the methanolic extract of whole plant parts [104,120]. Five compounds (63–64, 66–68) were found in aerial parts using different solvents such as methanol, ethanol, petroleum ether, and chloroform. Ten compounds (63, 65, 67, 71–77) were characterized from the fruit parts, and two compounds (69–70) were isolated from the alcoholic extract of seeds. Notably, compounds 63, 64, and 67 were commonly found in the whole plant, aerial parts, fruit, and shoot [104,105,110,121,122,123,124,125,126]. Seven compounds (71–77) were characterized from S. surattense fruit extract using different solvents, including ethanol, and petroleum ether [127,128,129,130,131].

Among all the plant parts of the S. surattense, the fruit contains the most diverse secondary metabolites, particularly glycoalkaloids and steroidal alkaloids. In this study, steroidal alkaloids such as solamargine (63), solasodine (65), solasonine (67), solanidine (72), solasurine (74), tomatidine (68), and solanearpidine (77) were found as principal compounds in the fruit and throughout the whole plant [104,105,110,121,125,128].

23.81% of the alkaloids, including solamargine (63), khasianine (64), and (22R, 25R)-16β-H-22α-N-spirosol-3β-ol-5-ene3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 4)]-β-D-glucopyranoside (66), exhibited anti-tumoral activity. Additionally, solasodine (65) and solasonine (67) demonstrated both anti-tumoral activity in vitro and antiurolithiatic activity in vivo.

Terpenoids: Terpenoids (78–214) are the major class, with 137 compounds (40.23%) identified. This class includes monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, and triterpenoids [104,107,111,112,114,115,121,122,127,131,132,135,138,139].

- Eight monoterpenoids (78–85), including 7Z-roseoside (78), linalool (79), camphor (80), α-terpineol (81), geraniol (82), isobornyl acetate (83), (E)-β-ionone (84), and dihydroactinidiolide (85), have been isolated from S. surattense leaf, fruit, seed, and root extracts using solvents like ethanol and aqueous solutions [105,132].

- Sixty-one sesquiterpenoids (86–146) have been identified from aqueous and methanol extracts of the leaf, fruit, seed, and root [113,114,132].

- Five diterpenoids (147–151), such as phytol (147), neophytadiene (148), (E,E)-geranyllinalool (149), lycopene (150), and carotenoids (151), have been characterized from aqueous, ethanol, and methanol extracts of the leaf and fruit [107,113,114,115].

- Sixty-three triterpenoids (152–214) have been identified from various parts, including the aerial parts, leaf, fruit, seed, stem, and whole plant, with the fruit being the major source [104,105,107,111,112,115,121,122,126,127,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139].

A total of 18.25% of terpenoids, predominantly triterpenoids, exhibited various biological effects. These include dioscin, (22R, 23S, 25R)-3β, 6α, 23-trihydroxy-5α-spirostane 6-O-β-dxylopyranosyl-(1 → 3)-O-β-D-quinovopyranoside, (22R, 23S, 25S)-3β, 6α, 23-trihydroxy-5α-spirostane 6-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1 → 3)-O-β-D-quinovopyranoside, (22R, 23R, 25S)-3β, 6α, 23-trihydroxy-5α-spirostane 6-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1 → 3)-O-β-D-quinovopyranoside (153–156), solasaponin A–H (161–168), diosgenin (173), xanthosaponin A–B (174–175), cholesaponin A–F (203–208), and (22S)-25[(β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-22-hydroxycholest-5-en-3β-yl-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-O-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 4)]-β-D-glucopyranoside (209). These compounds exhibited anti-tumoral activity, while carpesterol (177) and oleanolic acid (186) showed anti-diabetic activity in vitro and neuroprotective activity in vivo, respectively.

β-Sitosterol (182) and diosgenin (173) were obtained from the hydroethanolic extract of S. surattense calli. A higher content of β-sitosterol and diosgenin was quantified in tissue culture than in the fully grown S. surattense plant [126]. Gupta and Dutt investigated the constituents of the semi-drying oil obtained from the benzene extract of S. surattense seed and reported the presence of fatty acids, including oleic acid, linoleic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid, arachidic acid, and unsaponifiable matter (a mixture of two sterols) [141].

Lipids: Fifty-one compounds (15.08%) identified as lipids (215–266) encompass fatty acids, aldehydes, fatty alcohols, fatty amides, sphingolipids, oxylipins, and phenolic lipids [104,106,107,113,114,115,140,141,142].

- Eighteen fatty acids (215–232) have been isolated from the leaf, stem, fruit, root, and whole plant of S. surattense, with most of the compounds found in the leaf [104,107,113,114,115,140,141].

- Eleven aldehydes, including nonanal (233), (2E,4E)-decadienal (234), dodecanal (235), tridecanal (236), tetradecanal (237), pentadecanal (238), hexadecanal (239), 9,12,15-octadecatrienal (240), tetracosanal (241), pentacosanal (242), and hexacosanal (243), have been isolated from aqueous extracts of S. surattense, especially from the fruit [114].

- Three fatty alcohols, 1-octanol (244), (6Z)-nonenol (245), and (Z)-dihydroapofarnesol (246), were isolated from aqueous extracts of the fruit and seed, while two fatty amides, (9Z)-octadecenamide (247) and octadecanamide (248), were identified from the seed [114].

- Additionally, eight sphingolipids (249–256), seven oxylipins (257–263), and three phenolic lipids (264–266) have been identified from the fruit of S. surattense [142].

Lipids, accounting for 34.62%, were found to have anti-inflammatory potential in vitro. These include compounds such as 6′′-O-acetyl soya-cerebroside I (249), soya-cerebroside I-II (250–251), 2S,3S,4R,8E-2-(2′R-2′-hydroxyhexacosanosylamino)-octadecene-1,3,4-triol (252), gynuramide I-IV (253–256), methyl 9S,10S,11R-trihydroxy-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoate, 9S,10S,11R-trihydroxy-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoic acid, methyl 9S,10S,11R-trihydroxy-12Z-octadecenoate, 9S,10S,11R-trihydroxy-12(Z)-octadecenoic acid, methyl 9S,12S,13S-trihydroxyoctadeca-10E,15Z-dienoate, 9S,12S,13S-trihydroxy-10E-octadecenoate, 2′S-20-hydroxy arachidic acid glycerol ester (257–263), 2′S-20-O-caffeoyl-20-hydroxy arachidic acid glycerol ester, 2′S-22-O-caffeoyl-22-hydroxy-docosanoic acid glycerol ester, and 2′S-22-O-p-hydroxy-phenyl propionyloxy-22-hydroxy-docosanoic acid glycerol ester (264–266).

Some lipid compounds influence growth factors through phytohormones such as auxins (IAA and IBA), kinetin (Kn), and gibberellic acid (GA) in the callus culture of S. surattense [143,144]. Additionally, certain compounds of this chemical class exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in a paw edema carrageenan-induced inflammation model in rats and demonstrated in vitro anti-cancer activity against HeLa and U937 cell lines [125,145].

Several sources of the scientific literature have reported various quantitative analysis results in different plant parts like leaf, fruit, stem, stem bark, root, and root bark of S. surattense [113,146,147,148,149,150,151]. Among the different solvents used in extraction, methanol was the most used one for quantitative analysis. The quantitative analysis focused on determining the total phenolic, flavonoid, tannin, and terpenoid contents. The phenolic content was highest in the ethanol extract of S. surattense leaf, measuring 46.7 GAE/mg [146], followed by the acetone extract of S. surattense root at 28.9 g/100 g [150], while the lowest value of 4.975 GAE/mg was found in the methanol extracts of the fruit [147], indicating that ethanol solvent is probably the best solvent for more phenolic constituents.

The flavonoid content was highest in the ethyl acetate and acetone extracts of S. surattense fruit, measuring 162.4 ± 0.15 μg QE/mg and 148 ± 0.18 μg QE/mg, respectively [151]. In contrast, the methanol extracts of S. surattense leaf showed the lowest value at 2.48 ± 0.6 Rutin/µg [148]. In addition, the acetone extract of S. surattense root has the highest total tannin content of 18.7 g/100 g extract [150]. Regarding total terpenoid content, the highest content was 6.3 ± 1.2 GAE/mg in the methanol extract of S. surattense root [113]. Moreover, the quantification analysis differs in results based on plant parts, extracting solvents, and way of result expression. More details are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative phytochemical estimation of different extracts of S. surattense.

2.4. Pharmacological Studies

Extracts from the whole plant and various parts of Solanum surattense—including aerial part, leaf, fruit, flower, seed, stem, stem bark, and root—have been extensively studied for their biological activities. These results are comprehensively summarized in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Although there are no formal scientific reports on using S. surattense specifically against piles, traditional medicine in regions like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh frequently employs this plant for such conditions, often lauding it as a remarkable therapeutic agent. Notably, the ancient Indian text “Materia Medica” references S. surattense, particularly its root, for treating a variety of ailments, including piles [152], using methods like fumigation [89].

Table 4.

In vitro and in vivo pharmacological and toxicological studies based on S. surattense.

Figure 8.

Different biological activities (%) of S. surattense.

Figure 9.

Percentage of different plant parts of S. surattense used in different biological activities. Abbreviation: F—fruit; L—leaf; Wp—whole plant; Ap—aerial part; R—root; Stb—stem bark; Fl—flower; S—seed; B—bark; St—stem.

2.4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The anti-inflammatory properties of S. surattense are well-documented, particularly for its ethanolic extracts from leaf and fruit. These extracts exhibit significant activity in both in vivo and in vitro experiments [118,185,191,198]. The alcoholic extract of aerial parts, as well as a gel formulated with Carbopol 940 polymer, have been evaluated for wound healing potential using excision and incision wound models in male Wistar rats (180–220 g).

For the excision wound model, rats were divided into eleven groups (six animals per group):

- Groups 1 and 2: Normal topical control with Carbopol gel and normal oral control with distilled water;

- Groups 3 and 4: Diabetic topical control and diabetic oral control with Carbopol gel and distilled water, respectively;

- Groups 5 and 6: Diabetic treated topically with aloe vera cream and orally with aloe vera juice;

- Groups 7–10: Diabetic treated topically and orally with ethanolic extract of S. surattense ESX gel (5% w/w and 10% w/w) and ESX (100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg), respectively;

- Group 11: Diabetic treated with both topical (ESX gel 10%) and oral (200 mg/kg) treatments.

Significant effects were observed across all doses for both topical and oral treatments. The combination treatment (ESX Gel 10% + ESX 200 mg/kg) showed the most substantial wound closure (93.50 ± 1.60%), followed by ESX Gel 10% (88.33 ± 2.24%) and ESX 200 mg/kg (85.16 ± 1.27%). For the incision wound model, animals were divided into nine groups (excluding Groups 10 and 11 from the excision wound model), demonstrating a significant increase in wound-breaking strength (WBS), particularly in those treated with the combination therapy [167].

Parmar et al. (2010) investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of ethanolic leaf extracts using Sprague-Dawley rats (140–160 g) in a carrageenan-induced paw edema model. The extract (50–400 mg/kg, p.o.) significantly inhibited paw swelling at doses of 100, 200, and 300 mg/kg, with edema inhibition percentages of 31.57%, 46.31%, and 45.26%, respectively, at 3 h. These results were highly significant (p < 0.01) compared to the control [190].

Aqueous extracts of dried S. surattense fruit were evaluated for anti-inflammatory activity using the carrageenan-induced paw edema assay in Wistar Albino rats (150–300 g). Six groups were categorized: positive control, negative control, S. surattense group, Cassia fistula group, combinations 1 and 2. The S. surattense dried fruit extract showed superior anti-inflammatory properties compared to C. fistula, with the highest effects at a 500 mg/kg dose. The combination of S. surattense and C. fistula (1:1) exhibited synergistic efficiency, achieving 75% inhibition compared to 81% for diclofenac sodium [204].

Key anti-inflammatory components from S. surattense include stigmasterol [234], carpesterol [235], and diosgenin [236]. Other compounds such as solanidine, α-solanine, and α-chaconine also possess significant therapeutic potential against inflammation. Chronic inflammation, often seen in autoimmune diseases, cancer, vascular disorders, and arthritis, can be addressed by targeting key molecular pathways. Lupeol, identified in S. surattense, demonstrates immense anti-inflammatory potential as a multi-target agent, affecting pathways such as NFκB, cFLIP, Fas, Kras, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt/β-catenin. Remarkably, lupeol at therapeutic doses shows no toxicity to normal cells, making it a promising candidate for both preventive and therapeutic applications against inflammation [237].

2.4.2. Anti-Diabetic Activity

In the quest for advanced and effective anti-diabetic drugs, substantial research highlights the potential of various plants. S. surattense has shown prominent anti-diabetic properties comparable to the standard drug “Glibenclamide”. Sridevi et al. (2007) demonstrated that S. surattense leaf extract possesses antihyperglycemic potential in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic male Wistar Albino rats (150–300 g). Five groups (n = 6) were categorized: group I: normal rats receiving 2% gum acacia only; group II: normal + leaf extract (100 mg kg−1 bw) in 2% gum acacia; group III: diabetic control rats (STZ-40 mg kg−1 bw); group IV: diabetic + leaf extract (100 mg kg−1 bw) in 2% gum acacia; group V: diabetic + glibenclamide (600 μg kg−1 bw) in 2% gum acacia for this study. Extended oral administration of 100 mg/kg b.w. of leaf extract for 45 days significantly reduced blood glucose levels and increased insulin levels [177].

Gupta et al. (2011) identified β-sitosterol from S. surattense as having promising antidiabetic properties. For this study, male Wistar Albino rats (170–190 g) were used, and they were divided into nine experimental groups (n = 9), including a control group, a diabetic group, and BS- and glibenclamide-treated diabetic groups. A 21-day experiment showed increased serum insulin levels in the treated group compared to controls. Enhanced levels of pancreatic antioxidants, such as SOD, CAT, GSH, GST, GPx, and ascorbic acid, were also observed, confirming β-sitosterol’s antidiabetic and antioxidant effects [221].

2.4.3. Anti-Tumor Activity

S. surattense has a wide range of pharmacological properties, including anticancer efficiency. Both polar and nonpolar solvent extracts of S. surattense leaf and fruit showed potential inhibitory activity against cancer cell proliferation [118,151,238]. The methanol extract of S. surattense whole plant was responsible for apoptosis-inducing activity and causes cell death [239]. In another study, S. surattense leaf extract with the nanoparticle solution (silver nanoparticle solution (AgNPs)) also showed significant cytotoxicity [181].

The presence of different secondary metabolites such as lupeol, apigenin, stigmasterol, solancarpine, carpesterol, solamargine, diosgenin, and steroidal alkaloids enhances the cytotoxic activity. Lupeol, apigenin, and solamargine exhibit the potentiality of antitumor activity by enhancing apoptosis. Lupeol possesses up-regulation of melanogenesis through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway against B16 2F2 melanoma cells. Solamargine induces non-selective cytotoxicity and P-glycoprotein inhibition. Again, the appearance in solamargine-treated cells of chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and a sub-G1 peak in a DNA histogram suggests that solamargine induces cell death by apoptosis. Apigenin decreases the genotoxic damage induced by mitomycin C and cyclophosphamide and activates anti-cancerous potentials, thereby reducing the chances of developing secondary tumors [240,241,242,243]. Apigenin, quercetin, fisatin, and luteolin recorded from S. surattense fruit extracts act as potential inhibitors of cancer cell proliferation, e.g., human lung cancer cell lines (HOP-62) and leukemic (THP-1) cell lines [151,244]. Cham (2017) reported that solamargine and solasodine showed cytotoxicity against Hep 2 B cells of 10 µm [245]. Sethi et al. (2018) mentioned that diosgenin exhibited apoptosis activity on HCT 116 cell lines (human colon carcinoma cell lines) [168]. These findings of the study confirmed that the steroidal constituents (from S. surattense) are responsible for apoptosis-inducing activity and cause cell death. Through these systematic investigations, it is well explained how inducing apoptosis and cell death could potentially develop therapeutic drugs to overcome cancer.

2.4.4. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidants are a very important factor in improving health problems, and they can be isolated from traditional medicinal plants. Antioxidants can protect against oxidative damage [169]. Some plants have rich resources of antioxidants which have potential effects against reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. Therefore, the determination of natural antioxidant compounds of plant extracts will be helpful for the development of new drug candidates for antioxidant therapy [246]. The leaf contains a higher quantity of phenols and flavonoids than the stem and fruit. The presence of phenols and flavonoids in S. surattense has become a natural source of potential antioxidants and can be used as a medicine against diseases caused by free radicals [147]. Leaf extract of S. surattense enhanced the level of antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase in alloxan-induced animal models [173]. Meena et al. (2010) mentioned that methanolic and ethanolic extracts of S. surattense have potential antioxidant properties [29]. Joseph et al. (2011) estimated higher levels of total phenolics (28.9 g/100 g extract) and tannins (18.7 g/100 g extract) in the acetone extract of S. surattense root that has the potentiality to exhibit higher activity against DPPH, ABTS+, OH− radical scavenging, and phosphomolybdenum reduction [150]. Nithiyanantham et al. (2012) reported that S. surattense fruit aqueous extract exhibited good scavenging and reducing potentiality against DPPH and FRAP with the values of 2.1 ± 0.2 and 2.5 ± 0.0 (boiled) g extract/g DPPH, and 7.0 ± 0.0 and 28.5 ± 0.0 (boiled) µg extract/mmol Fe(II) [149]. Muruhan et al. (2013) reported that the significant scavenging efficiency of S. surattense leaf extracts against 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl has shown remarkable antioxidant activity at all test doses in a dose-dependent manner [146]. Kumar and Pandey (2014) measured free radical scavenging activity by DPPH assay at different concentrations of 250, 500, and 1000 μg/mL. In the DPPH radical scavenging assay, most of the S. surattense fruit extracts (chloroform, ethyl acetate, acetone, ethyl alcohol, and water extracts) demonstrated appreciable radical scavenging activity at a 250 μg/mL concentration, revealing considerable antioxidant potential in the extracts where total flavonoid contents (ranged between 10.22–162.49 μg quercetin equivalent/mg) showed a positive correlation with antioxidant activity [151]. Shah et al. (2013) explained that fruit extracts possess an appreciable amount of radical scavenging activity (about 80%) at a concentration of 250 µg/mL, but no changes at increased test dose concentrations of 500 and 1000 µg/mL (due to the saturation effect) [197]. Poongothai et al. (2011) reported that methanol extract of S. surattense leaf enhanced the level of antioxidant enzymes catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione (GSH) peroxidase in alloxan-induced animal models. Antioxidants increased to the normal level, and the efficiency showed similar to standard drug glibenclamide. The antioxidant potentiality of S. surattense leaf extracts might be attributed to the presence of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in high quantities [173]. According to Azhar et al. (2020), the methanol extract of the stem bark, with an IC50 value of 0.323102 mg ml−1, had the highest potential for antioxidant activity [148]. These findings confirm that S. surattense would be an effective natural source of antioxidants.

2.4.5. Antibacterial Activity

Many studies have highlighted the antibacterial properties of plant extracts from S. surattense. Ahmed et al. (2009) found that methanol and aqueous extracts from different plant parts (fruit, shoot, root) were effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, with the fruit extract showing the highest activity [42]. Sheeba (2010) reported significant antibacterial effects of ethanol leaf extracts against eight bacterial strains [179]. Nithiyanantham et al. (2012) noted the antimicrobial activity of aqueous fruit extracts against gram-negative bacteria [149]. Abbas et al. (2014) observed that fruit extracts inhibited various bacterial strains, with varying zones of inhibition [195]. Mickymaray et al. (2016) found ethanolic aerial part extracts effective only against E. coli [247]. Another study showed high sensitivity of different plant part extracts to Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella typhi, with varying effectiveness against other bacteria [228]. Choudhary et al. (2016) reported that the whole plant aqueous extract exhibited significant antibacterial activity at high concentrations [154]. Different solvent extracts of S. surattense leaf showed varying degrees of effectiveness against several bacterial strains, with methanol extracts being the most effective [113]. Another study demonstrated that methanol, ethanol, and chloroform extracts of the whole plant had different minimum inhibitory concentrations against Staphylococcus cohnii. Overall, these studies highlight the broad antibacterial potential of S. surattense extracts [153].

2.4.6. Antiviral Activity

The anti-HIV reverse transcriptase (RT) activity of different solvent extracts of S. surattense fruit has been evaluated, showing dose-dependent inhibitory effects at concentrations of 0.6 and 6.0 μg/mL. Benzene and acetone extracts demonstrated significant RT inhibition [151].

2.4.7. Antifungal Activity

Methanol extracts of S. surattense fruit have shown broad-spectrum antifungal effectiveness, inhibiting the growth of fungal strains such as Trichoderma viride, Aspergillus niger, A. flavus and A. Fumigatas. Singh et al. (2007) reported that the antifungal efficiency of isolated steroidal glycosides exhibited inhibitory effects on the radial growth of A. niger and T. viride, where T. viride exhibited the highest susceptibility and showed the highest growth inhibition antifungal effect of plant extracts compared with the standard drug amphotericin-B [196]. David et al. (2010) reported that among the aqueous, ethanolic, and methanolic extracts of S. surattense seed, ethanol seed extracts showed high antifungal activity against Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, A. niger, A. fumigates and A. flavus; methanol extracts showed activity against A. fumigatus and Rhizopus oryzae; and aqueous extracts showed activity only against C. albicans [218]. Jinal and Amaresan (2020) also evaluated that aqueous-ethanol root extract showed antifungal activity against R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum, respectively [226].

2.4.8. Antihelminthic Activity

Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of S. surattense fruit showed anthelminthic activity against Pheritima posthuma, whereas aqueous extract showed better anthelmintic activity in comparison to the ethanol extract [200]. Priya et al. (2010) recorded that aqueous, hydroethanolic, and ethanolic extracts of S. surattense showed anthelminthic activity at 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL conc. Here, ethanolic extracts showed a remarkable anthelmintic potentiality compared to aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts at a concentration of 100 µg/mL [159]. In another study, ethanol extract of S. surattense fruit showed anthelminthic activity against P. posthuma at different concentrations (10, 25, and 50 mg/mL) and caused paralysis and death [199]. Barik et al. (2018) mentioned similar findings on the anthelminthic efficiency of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of S. surattense fruit [205].

2.4.9. Cardiovascular Activity

Pasnani (1988) investigated the cardiovascular effects of Abana, a formulation containing solasodine from S. surattense. The study found that Abana caused direct sensitization of the atrium and downregulation of beta-adrenoceptors [248].

2.4.10. Hepatoprotective Activity

Hepatic diseases, often caused by oxidative stress and inflammation, are a serious health concern. Traditional Ayurvedic medicine uses S. surattense fruit to treat liver disorders. Gupta et al. (2011) investigated the hepatoprotective potential of S. surattense fruit ethanolic extract applied to CCl4-induced (carbon tetrachloride) acute liver toxic experimental animals. A total of six groups (n = 6) of Sprague-Dawley rats were made, where Group I was considered as the control group and administered a single daily dose of carboxymethyl cellulose (1 mL of 1%, w/v, p.o. body weight). Group II received carbon tetrachloride (1 mL/kg b.w., i.p. 1:1 v/v mixture of CCI4 and liquid paraffin) alone, while groups III, IV and V received orally 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg body weight of ethanolic (50%) extract of S. surattense in (1%, w/v, CMC), respectively. And group VI received silymarin, the known hepatoprotective compound (standard), at a dose of 100 mg/kg, p.o., along with carbon tetrachloride. The fruit extract at a dose of 400 mg/kg showed a significant effect on lowering the serum marker enzymes, where reduction in the level of serum marker enzymes is comparable between the CCl4 group and Silymarin. The percentage protection in marker enzyme of treated groups (III, IV, and V) at the dose of 400 mg/kg was AST 67.71, ALT 75.66, ALP 54.52 compared to the silymarin treated group VI at the dose of 100 mg/kg as AST 70.36, ALT 77.40, ALP 59.80 [221].

Ghassam et al. (2014) conducted a similar study, finding that the leaf methanolic extract decreased serum LDH, ALP, and AST levels significantly (1.7-fold, 1.6-fold, and 1.8-fold, respectively). At a dose of 200 mg/kg extract, SOD, CAT, GST, and GSH levels in liver homogenates were increased (1.78 ± 0.13, 34.63 ± 1.98, 231.64 ± 14.28, 8.23 ± 0.48). Albino Wistar rats weighing 180–200 g were used in this study. Animals were categorized into five groups (n = 6); group I: sterile distilled water (positive control), group II: CCl4 (negative control), group III: 100 mg/kg b.w. of SXAF (S. surattense active fraction) orally for 14 d + single oral dose of CCl4 on the 15th day (1 mL/kg b.w.), group IV: 200 mg/kg b.w. of SXAF orally for 14 d + single oral dose of CCl4 on the 14th day and group V: 25 mg/kg b.w. of silymarin orally for 14 d + single oral dose of CCl4 on the 14th day. Histopathological examination also showed lowered liver damage in CCl4-induced groups [183].

Singh et al. (2016) noticed the hepatoprotective potential of S. surattense fruit extracts combined with Juniperus communis against Paracetamol (PCM) and Azithromycin (AZM) induced hepatic injury. Wistar albino rats of either sex (150–200 g) were used, and total experimental procedures were conducted in eight experimental groups (n = 6) in this study. The administration of AZM and PCM significantly produced liver toxicity by increasing the serum level of hepatic enzymes (SGPT, SGOT, and ALP) and oxidative parameters causing liver damage in rats. Administration of S. surattense fruit extract (200 and 400 mg/kg) and J. communis (200 and 400 mg/kg) for 14 days significantly attenuated the liver enzymes (SGPT, SGOT, and ALP) in AZM and PCM-treated animals. The findings indicated that S. surattense fruit extracts have hepatoprotective potential due to their synergistic antioxidant properties [193].

Jigrine is a combination of 14 medicinal plants including S. surattense in aqueous extract form, used to treat various liver conditions as a polypharmaceutical herbal hepatoprotective formulation. Najmi et al. (2005) investigated the DPPH-free radical scavenging activity, hepatoprotective, and antioxidant activity of Jigrine against galactosamine-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Wistar strain albino rats (150–200 g) were used for the study and categorized into four groups (n = 6). Both positive and negative controls were used here. In Galactosamine-induced animals, a significant increase in serum AST, ALT, urea, and tissue TBARS levels was observed and analyzed to assess liver function. Administration of Jigrine (1 mL/kg, p.o.) for 21 days decreased the levels of the above indices significantly. The biochemical data exhibited significant hepatoprotective activity against galactosamine-induced rat models [249].

According to this review, antimicrobial (36%), antioxidant (21%), anti-inflammatory (12%), and cytotoxic activities (12%) were the most reported activities of this species, where antimicrobial activity showed the highest percentage (Figure 8).

Similarly, the most used extracts were ethanolic (47.37%), and the most used plant parts were fruit (29%) and leaf (28%) (Figure 9).

2.5. Pharmacological Activity of Secondary Metabolites of S. surattense

Fifty-five isolated compounds from S. surattense that were biologically tested and studied for their potential bioactivities by different researchers demonstrated anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory are the most remarkable activities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biologically tested compounds of S. surattense.

Several active compounds from S. surattense have been reported to strongly bind to the target proteins, potentially inhibiting their functions or mechanisms, indicating their therapeutic potential by in silico method. Marker secondary metabolites such as quercetin and heptahydroxy flavone interact with the following proteins: AKT1 (AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1), BCL2L1(Bcl-2-like protein 1), EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor), ESR (Estrogen Receptor), H1F1-α (Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1-alpha), HRAS (Harvey Rat Sarcoma Virus), mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), TNF (Tumor Necrosis Factor). Also, solanidine interacts with AKT1, EGFR, H1F1-α, mTOR; esculetin, with BCL2L1 and TNF; Leptinidine, with ESR; and Verazine with HRAS and creates a strong binding force with these target proteins. These interactions suggest that these compounds can inhibit cell proliferation and have shown therapeutic effects against hepatocellular carcinoma [250].

In another study, Hasan et al. (2020) reported that the C3-like protease of SARS-CoV-2 raises the possibility of their acting therapeutically against the virus. Marker secondary metabolites from S. surattense, such as α-solamargine, bind strongly with both catalytic residues His41 and Cys145, and other residues including Ser46, Ser144, His163, Asn142, Glu166, Met49, and Gln189. It also binds with inhibitor N3 residues: His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, His163, His164, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, Gln189, Thr190, and Ala191. Similarly, solanine interacts with catalytic residues Cys145 and His41 as well as other residues such as His163, His164, Met165, and Pro168 and Asp187, Gln189, and Ala191, and interacts with inhibitor N3 residues Met49, His163 and His164. Solasurine interacts with Phe8, Pro9, Ile152, Tyr154, Pro293, Phe294, Val297, and Arg298; tomatidenol binds with catalytic residue Cys145, and other residues like Ser144, Pro168 and Ala191. Carpesterol interacts with Arg40, Cys85, Phe 134, and Pro 184, creating a strong bond [251].

Also, apigenin, chlorogenic acid, stigmasterol, and stigmasterol glycoside were found to create strong bonds with target proteins such as EGFR, TP53, ERBB2, and STAT3, providing therapeutic effects against psoriasis [252].

2.6. Clinical Studies

Govindan et al. (1999) performed a pilot experiment on the clinical efficacy and safety of a single dose in mild to moderate bronchial asthma resulting in relief from asthmatic symptoms after 1 h, and its effect lasted for about 6–8 h. The respiratory functions (FVC, FEV1, PEFR, and FEF25–75%) were assessed by using a spirometer before and 2 h after the oral administration of 300 mg powder of the whole plant S. surattense. Treatment with S. surattense significantly improved the various parameters of pulmonary function in asthmatic subjects [26]. Govindan et al. (2004) studied the clinical efficacy of S. surattense and S. trilobatumin in bronchial asthma. For the clinical efficacy, a dose of 300 mg for 3 days was administered orally in mild to moderate bronchial asthma. S. surattense and S. trilobatum produced a progressive improvement in the ventilatory function of asthmatic individuals over 3 days. The scores for rhonchi, cough, breathlessness, and sputum decreased with these drug treatments. The improvement in PEFR and the reduction in other symptom scores clearly indicate a bronchodilator effect and a decrease in edema and secretions in the airway lumen. These clinical trials proved the anti-asthmatic potential, which is important for the management of asthma [253]. Another experiment was performed by Divya et al. (2013) where anti-asthmatic activity of the polyherbal ayurvedic drug was observed in in vitro and in vivo conditions. This trial on 60 bronchial asthmatic patients resulted in significant improvement in pulmonary expiratory flow rate (PEFR), forced vital capacity (FVC), and forced expiratory volume (FEV), indicating that constant improvement was observed throughout the follow-up with no recurrence of bronchial constriction [254]. Joshi et al. (2021) conducted a randomized clinical trial on gingivitis on 75 patients considering the safety and efficacy to assess the properties of two herbal mouth rinses (S. surattense and Acacia catechu Willd) and compare the herbal mouth rinses with Chlorhexidine (Gold standard) [255].

Especially in India, several herbal medicines based on S. surattense are available on the market, such as S. xanthocarpum powder and tablets (Bharat Herbal, India), Indukantham Kashayam (Planet Ayurveda, Punjab, India), Koflet (Himalaya Wellness Company, Bengaluru, India), Mother Tincture Solanum xanthocarpum (Dr. Willmar Schwabe India Pvt. Ltd., Delhi, India), and Kantakari powder and capsules (DR WAKDE’S Natural Health Care, London, UK). However, these products are neither approved nor controlled by the Indian Drug Control Agency, and no information regarding their quality, safety, and efficacy is available in the literature. Additionally, a Chinese patent was identified, describing the preparation and administration of an ethanolic herbal formulation from S. surattense fruit. This formulation contains 80 to 99% total weight (wt%) of solancarpine (30–50 wt%), solamargine (10–30 wt%), and solasurine (30–50 wt%), and is intended for the prevention and treatment of diseases such as tumors, diabetes, asthma, and coronary heart disease [256].

2.7. Toxicological Studies

Baskar et al. (2018) studied the toxic effect on Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.), Culex quinquefasciatus (Say.), and Eisenia fetida (Savigny) by using hexane (H), chloroform, and ethyl acetate (E) extracts. The chloroform extract exhibited maximum larvicidal activity of 71.55% against H. armigera with the least EC50 value of 2.95%, followed by ethyl acetate extract which showed larvicidal activity of 40.88% with an EC50 value of 5.36%. The lower larvicidal activity was recorded in hexane extract with a higher EC50 value of 6.61% concentration. Maximum pupicidal activity of 83.33% was recorded in chloroform extract of S. surattense against H. armigera and the EC50 value was 1.96%. The minimum pupicidal activity of 35.23% was recorded at 5.0% concentration in hexane extract. In the case of EC50 value, ethyl acetate extract was the least toxic. At 5.0% concentration, the hexane and ethyl acetate extracts showed statistically similar activities. Based on the bio-efficacy result, the chloroform extract was fractionated into 9 fractions (F) with increasing polarity of the solvent system with hexane, ethyl acetate, and acetone. Among these fractions, F4 (H70: E30) showed the highest effectivity. The F4 showed acute toxicity against H. armigera at 1500 and 2000 ppm concentrations. All the concentrations (125, 250, 375, 500 ppm) of F4 showed acute toxicity against Cx. quinquefasciatus with an LC50 value of 225.70 ppm. None of the concentrations (31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg dry weight of soil concentration) tested exhibited toxic symptoms or abnormal behavior, nor did they result in mortality of E. foetida within the 14-day observation period, and the LC50 value was >1000 mg/kg dry weight of soil [162].

The acute toxicity effect of the ethanol extract of S. surattense on Swiss albino mice at high concentrations of 100 and 200 mg/kg body weight (oral administration) was reported by Sravanthi et al., 2013 where no changes in the normal behavior of mice, and no signs of toxicity or mortality were observed. In LD50 tests, it was found that the animals were safe up to a maximum dose of 2 gm/kg body weight [257]. Gupta et al. (2011) also investigated acute toxicity on Swiss albino mice (6 groups). The ethanolic (50%) extract of S. surattense fruit was administered orally at doses of 250, 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 mg/kg body weight. No mortality was observed at 2000 mg/kg, leading to the selection of 200 mg/kg as the therapeutic middle dose, with 100 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg chosen as the low and high doses, respectively [258].

A study investigated the 95% ethanolic extract of S. surattense for acute toxicity and determined the maximum lethal doses for 24 h exposure, where it was determined the doses of 8.64 mg/L and 17.28 mg/L caused 100% mortality to the fish. And this extract also effectively killed mature and young snails at 4.321 mg/L [208]. In another study, α-solamargine, one of the active components obtained from the 95% ethanolic extract of S. surattense fruit, shows an effective activity of killing (100% at 28 °C) Oncomelania snails in an α-solamargine solution (0.2 mg/L) [130]. Using in vivo tests on 8 groups of sourian mice, the first 7 groups were infected with P. berghei and treated with chloroquine, four different concentrations of S. surattense (20, 100, 300, 450 mg/kg), placebo, or no treatment. By day 4, chloroquine completely cleared parasitaemia (0%), while the 450 mg/kg S. surattense group reduced parasitaemia to 4.19%. Placebo and untreated groups showed high parasitaemia (17.2% and 17.8%) with increased levels on day 7. Chloroquine extended survival to 29 days, while the 450 mg/kg S. surattense group had a survival of 22 days, compared to 10–14 days in other extract-treated groups. No toxicity was observed in any treatment group [155].

The hepatoprotective activity was demonstrated for the 50% ethanolic extracts of S. surattense against antitubercular drug (isoniazid (I) 7.5 mg/kg, rifampicin (R) 10 mg/kg and pyrazinamide (P) 35 mg/kg)-induced hepatotoxicity, using various biochemical parameters like serum enzymes: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatise (ALP), total bilirubin (TBL), albumin (ALB), total protein (TP), lactate dehydroginase (LDH), and serum cholesterol (CHL). Acute liver toxicity resulting from antitubercular drug administration, showed massive fatty changes, focal necrosis with portal inflammation, and loss of cellular boundaries (indicated by the circle) and enhanced the levels of serum enzymes as well as hepatic enzymes. The 50% ethanolic extracts of S. surattense (400 mg/kg) inhibited the elevations of these markers by 122.37 ± 5.54, 57.27 ± 5.33, 72.65 ± 6.64, 0.85 ± 0.14, 3.97 ± 0.01, 5.89 ± 0.02, 516.21 ± 3.00, 45.12 ± 2.00, respectively. This was compared with the standard silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight), which reversed the elevation of these markers by 109.89 ± 4.43, 52.84 ± 4.72, 68.34 ± 6.21, 0.83 ± 0.13, 4.68 ± 0.05, 6.22 ± 0.12, 504.23 ± 3.94, and 36.12 ± 1.90, respectively [209].

Another study illustrated the protective effects of the ethanolic (50%) extract of S. surattense whole plant against Isoniazid and Rifampicin (INH + RIF (50 mg/kg))-induced hepatotoxicity. The extract, at doses of 125 and 250 mg/kg body weight, suppressed the INH + RIF-mediated increase in serum glutamate oxalate transaminase and serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase levels, and restored total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase to normal values [259]. A similar study found that administering ethanolic (50%) extract of S. surattense fruit (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg body weight) daily for 35 days in experimental animals protected against liver toxicity induced by a combination of three antitubercular drugs [isoniazid (INH) 7.5 mg/kg, rifampicin 10 mg/kg, and pyrazinamide (P) 35 mg/kg]. The hepatoprotective activity was assessed using various biochemical parameters, including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, albumin, total protein, lactate dehydrogenase, and serum cholesterol. The results demonstrated that treatment with S. surattense significantly (p < 0.05–p < 0.001) and dose-dependently prevented drug-induced increases in serum levels of hepatic enzymes. Histopathological analysis showed reduced hepatocellular necrosis and inflammatory cell infiltration, indicating the hepatoprotective activity of S. surattense [209].

The herbicidal effectiveness of S. surattense fruit extract was evaluated using a phytotoxic assay on maize seeds with methanolic solutions at 100, 250, 500, and 1000 µg/mL. The extract showed dose-dependent inhibition, with the highest concentration (1000 µg/mL) causing maximum inhibition of root (70.45%) and shoot (63.45%) growth of zea maize. The results demonstrated significant suppression of maize seedling growth compared to the control (methanol) [197].

2.8. Other Uses

The study reveals that the species investigated have a significant impact on nutritional value. Mali and Harsh (2014) estimated the protein content of leaf and seed at 11.11% and 12.83%, respectively. Additional findings include carbohydrate content at 75.08% and 71.74%, and crude fiber content at 33.91% and 20.24%. The mineral element composition (mg/100 g) of leaf and seed includes calcium at 1.17 and 1.52, potassium at 0.19 and 0.22, sodium at 0.10 and 0.02, and phosphorus at 0.39 and 0.51, respectively. Phytochemical analysis also revealed high levels of ascorbic acid [44]. Another study estimated total mineral content at 5.093 ± 0.015%, calcium content at 34.44 ± 1.92 mg/100 g, selenium content at 144.80 ± 0.01 mg/100 g, and iron content at 8.87 ± 0.03 mg/100 g [260]. These results indicate that this species has significant nutritional value when used as a vegetable.

Currently, highly toxic and carcinogenic chemicals are used to produce dyes, which harm human health and disrupt ecosystems. The global demand for natural dyes has increased due to their beneficial properties. Tayade et al. (2016) used green techniques to extract dye from S. surattense leaf for the finest color. This dye is important for both dyeing and pharmaceutical applications due to its medicinal value [261].

3. Materials and Methods

This review was performed following the criteria described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement 2020 [http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram.aspx (accessed on 10 December 2023)]. The PRISMA checklist with detailed information is added as Table S3 in the Supplementary Material.

3.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review adheres to PRISMA methodology and analyzes scientific publications between 1753 and 2023 from B-on, Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Web of Science. To ensure the quality and reliability of the nonrandomized studies included in this review, each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). This scale evaluates studies based on three broad criteria: the selection of the study groups, the comparability of the groups, and the ascertainment of the exposure or outcome of interest. Each study was scored accordingly to determine its methodological rigor. The explicit mention of NOS ensures that the quality of the nonrandomized studies is systematically evaluated, thereby enhancing the reliability and credibility of the findings presented in the review. Solanum surattense, Solanum xanthocarpum, ethnomedicinal value, traditional use, phytochemical analysis, and pharmacological activities were used as search keywords.

3.2. Data Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Relevant studies on S. surattense concerning medicinal importance.

- Full text in English.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Duplicate scientific publications;

- Not directly related to the medicinal issues;

- Containing non-relevant or incomplete information.

4. Conclusions

This systematic review will play an important role in providing complete knowledge on S. surattense as an important natural source of many ethnomedicinal and pharmacological perspectives. It has been used in traditional medicine to cure various ailments since ancient times by traditional practitioners. The literature study indicates the presence of different bioactive secondary metabolites from this species which are very important in both Ayurvedic and modern drug development areas. Additionally, different pharmacological activities have been shown by different plant parts. Systematic investigation ensures that most pharmacological studies were preliminary, carried out in animal models but are not sufficient for the development of a pharmaceutical product. At the present time, alternative drugs as herbal drugs, or herbal drugs with synthetic drugs have become popular for the safety and efficacy of natural products. It could lead to the exploration of new methods for therapeutic and industrial application. So, the present review concludes that the traditional medicinal plant S. surattense is a potent source of phytochemicals and pharmacological importance for future pharmaceutical use.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph17070948/s1, Table S1. Ethnomedicinal uses of S. surattense; Table S2. List of identified compounds found in S. surattense; Table S3. PRISMA Checklist with Detailed Information.

Author Contributions

K.H.: Conceptualization, information collection, writing original manuscript; S.S.: writing and editing; J.F.P. and N.I.: Revising the manuscript; O.S.: Supervision, conception, and study design, editing, and revising the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) through national funds to iMed.ULisboa (UIDP/04138/2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that the contents of this article have no conflicts of interest.

References

- POWO (Plants of the World Online). Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Linnaeus, C. Verbena. In Species Plantarum, 1st ed.; Impensis GC Nauk: Berlin, Germany, 1753; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Burman, N.L. Burmanii, Flora Indica: Cui Accedit Series Zoophytorum Indicorum, Nec Non Prodromus Florae Capensis; Cornelius Haek: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1768; p. 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharder, H.A.; Wendland, I.C. Sertvm Hannoveranvm Sev Plantae Rariores Qvae. In Hortis Regiis Hannoverae Vicinis Colvntvr; Vandenhoeck Et Ruprecht: Goettingae, Hannoverae, 1795; Volume 1, p. 600. Available online: https://digitale-sammlungen.gwlb.de/resolve?PPN=742569349 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Clarke, C.B. Solanaceae. In Flora of British India; New Connaught Place: Dehradun, India, 1885; Volume 4, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Rechinger, K.H. Solanaceae. In Symbolae Afghanicae; Kommission hos Ejnar Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1958; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, R.J. Flora of Presd. Bomb; Bombay Press: Mumbai, India, 1967; Volume 2, p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, J.Y. Solanaceae. In Flora of Pakistan; Fascicle; National Herbarium, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council: Islamabad, Pakistan, 1985; Volume 168, pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.U.; Begum, Z.N.T.; Hassan, M.A.; Khondker, M.; Kabir, S.M.H.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, A.T.A.; Rahman, A.K.A.; Haque, E.U. Encyclopedia of Flora and Fauna of Bangladesh; Asiatic Society: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopoeias. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India, Part-1; Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of AYUSH: New Delhi, India, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Flora of China Editorial Committee. Flora of China Editorial Committee. Flora of China (Checklist & Addendum). In Unpaginated; Wu, C.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Fl. China; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, C. Solanum xanthocarpum S. & W. In Indian Medicinal Plants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://10.1007/978-0-387-70638-2_1525.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Vattakaven, T.; George, R.; Balasubramanian, D.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Muthusankar, G.; Ramesh, B.; Prabhakar, R. India biodiversity portal: An integrated, interactive and participatory biodiversity informatics platform. Biodivers. Data J. 2016, 4, e10279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P. A review on the pharmaceutical activity of Solanum surattense. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 7, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekuri, S.K.; Pasupuleti, S.K.; Konidala, K.K.; Amuru, S.R.; Bassaiahgari, P.; Pabbaraju, N. Phytochemical and pharmacological activities of Solanum Surattense Burm f.—A Review. J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Gangwal, A.; Navin, S. Solanum Xanthocarpum (Yellow Berried Night Shade): A Review. Der. Pharm. Lett. 2010, 2, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Joghee, S. Solanum Xanthocarpum: A Review. IPCM 2019, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laware, S.G.; Shirole, N.L. A systematic review on Solanum xanthocarpum (solanaceae) plant and its potential pharmacological activities. Inter. Res. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 01–09. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Ahmad, S.; Sadiq, A.; Alam, K.; Wariss, H.M.; Ahmad, I.; Hayat, M.Q.; Anjum, S.; Mukhtar, M. A comparative ethno-botanical study of cholistan (an arid area) and pothwar (a semi-arid area) of Pakistan for traditional medicines. J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Mahmood, A.; Mahmood, A.; Tahir, S.S.; Bano, A.; Malik, R.N.; Hassan, S.; Ishtiaq, M. Relative importance of indigenous medicinal plants from Layyah district, Punjab province, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, M.R.; Shah, N.A.; Shah, S.A.; Majid, M.; Farooq, M.A. Ethnomedicinal plant use value in the Lakki Marwat district of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 158, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabesh, J.E.M.; Prabhu, S.; Vijayakumar, S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in silent valley of Kerala, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeva, S.; Femila, V. Ethnobotanical investigation of Nadars in Atoor village, Kanyakumari district, Tamilnadu, India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S593–S600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.M.; Rastogi, S.; Rawat, A.K.S. Indian traditional ayurvedic system of medicine and nutritional supplementation. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 376327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.P.; Malla, S.B.; Rajbhandari, S.B.; Manandhar, A. Medicinal plants of Nepal—Retrospect and Prospects. Econ. Bot. 1979, 33, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Vijayasekaran, V.; Alagappan, R. A pilot study on the clinical efficacy of Solanum xanthocarpum and Solanum trilobatum in bronchial asthma. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 66, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, G.; Meena, M. Bioprospecting of endophytes in medicinal plants of Thar Desert: An attractive resource for biopharmaceuticals. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, V.C.; Singh, A.G.; Tewari, D.D. Traditional uses of medicinal plants for dermatological healthcare management practices by the Tharu tribal community of Uttar Pradesh, India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.K.; Rao, M.M. Folk herbal medicines used by the Meena community in Rajasthan. Asian J. Tradit. Med. 2010, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik, B.K.; Panda, T.; Padhy, R.N. Traditional herbal practices by the ethnic people of Kalahandi district of Odisha, India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S988–S994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazani, A.; Zakeri, S.; Sardari, S.; Khodakarim, N.; Djadidt, N.D. In vitro and in vivo anti-malarial activity of Boerhavia elegans and Solanum surattense. Malar. J. 2010, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirbalouti, A.G.; Jahanbazi, P.; Enteshari, S.; Malekpoor, F.; Hamedi, B. Antimicrobial activity of some Iranian medicinal plants. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2010, 62, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, S.A.; Khan, A.M.; Qureshi, R.A.; Sherwani, S.K.; Khan, R.U.; Bokhari, T.Z. Advances in bioresearch ethno-medicinal treatment of common gastrointestinal disorders by indigenous people in Pakistan. Adv. Biores. 2014, 5, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Umair, M.; Altaf, M.; Bussmann, R.W.; Abbasi, A.M. Ethnomedicinal uses of the local flora in Chenab Riverine Area, Punjab Province Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.; Ditta, A.; Ibrahim, F.H.; Murtaza, G.; Rajpar, M.N.; Mehmood, S.; Saleh, M.N.B.; Imtiaz, M.; Akram, S.; Khan, W.R. Quantitative ethnobotanical analysis of medicinal plants of high-temperature areas of Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Plants 2021, 10, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.U.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, A.; Aziz, M.A.; Alam, N.; Sher, H.; Ali, I. Traditional knowledge of medicinal flora among tribal communities of Buner Pakistan. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaib, M.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, K.; Ilyas, M.; Hussain, F.; Urooj, Z.; Shah, S.S.; Kumar, T.; Shah, M.; Khan, I.; et al. Ethnobotanical and ecological assessment of plant resources at district Dir, Tehsil Timergara, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, R.B.; Bibi, T.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M. Indigenous knowledge of folk medicine by the women of Kalat and Khuzdar Regions of Balochistan, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 1465–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, F.; Ahmad, H.; Alam, M. Traditional uses of medicinal plants of Nandiar Khuwarr catchment (district Battagram), Pakistan. J. Medicinal Plants. 2011, 5, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.F.; Mashwani, Z.-R.; Mehmood, A.; Qureshi, R.; Sarwar, R.; Ahmad, K.S.; Quave, C.L. An ethnopharmacological survey and comparative analysis of plants from the Sudhnoti District, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matin, A.; Khan, M.A.; Ashraf, M.; Qureshi, R.A. Traditional use of herbs, shrubs and trees of Shogran valley, Mansehra, Pakistan. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2001, 4, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Kanwal, R.; Ayub, N.; Hassan, M. Assessment of antibacterial activity of Solanum surrattense against waterborne pathogens isolated from surface drinking water of the Potohar region in Pakistan. HERA 2009, 15, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Santra, S.C. Development of Tibetan plant medicine. Sci. Cult. 1976, 45, 262–265. [Google Scholar]

- Mali, M.C.; Harsh, N. Nutritional value estimation of the leaves and seeds of Solanum Surattense. J. Medicinal Plants 2015, 3, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dangwal, L.R.; Sharma, A. Indigenous traditional knowledge recorded on some medicinal plants in Narendra Nagar Block (Tehri Garhwal), Uttarakhand. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2011, 2, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, S.S.; Padhy, R.N. In vitro antibacterial efficacy of plants used by an Indian aboriginal tribe against pathogenic bacteria isolated from clinical samples. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2015, 10, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshad, S.M.R.; Iqbal, Z.; Muhammad, G.; Iqbal, A.; Ahmed, N. An inventory of the ethnoveterinary practices for reproductive disorders in cattle and buffaloes, Sargodha district of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinhababu, A.; Banerjee, A. Ethno-botanical study of medicinal plants used by tribals of Bankura Districts, West Bengal, India. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2013, 1, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, F.; Hussain, T.; Abdullah, M.; Ashraf, I.; Ch, K.M.; Rafay, M.; Bibi, I. Ethnobotanical survey; common medicinal plants used by people of Cholistan desert. Prof. Med. J. 2015, 22, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rajalakshmi, S.; Vijayakumar, S.; Arulmozhi, P. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Thanjavur and its surrounding (Tamil Nadu–India). Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, H.; Sharma, Y.P.; Manhas, R.K.; Kumar, K. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the villagers of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullaiah, T. Medicinal Plants in India; Regency Publications: New Delhi, India, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 474–475. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, R.; Waheed, A.; Arshad, M.; Umbreen, T. Medico-ethnobotanical inventory of tehsil Chakwal, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, A.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Yaseen, G.; Zada Khan, M.P.; Butt, M.A.; Sultana, S. Ethnopharmacological relevance of medicinal plants used for the treatment of oral diseases in Central Punjab-Pakistan. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 12, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Iqbal, W.; Sheraz, M.; Javed, B.; Zehra, S.S.; Abbas, H.A.B.E.; Hussain, W.; Sarwer, A.; Mashwani, Z.-R. Ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants in Bajwat wildlife sanctuary, district Sialkot, Punjab province of Pakistan. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5547987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, R.; Raza Bhatti, G.; Memon, R.A. Ethnomedicinal uses of herbs from Northern part of Nara desert, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 839–851. [Google Scholar]

- Badshah, L.; Hussain, F. People preferences and use of local medicinal flora in district Tank, Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Napagoda, M.T.; Sundarapperuma, T.; Fonseka, D.; Amarasiri, S.; Gunaratna, P. Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Polonnaruwa district in North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Scientifica 2019, 2019, 9737302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Abideen, Z.; Adnan, M.Y.; Ansari, R.; Gul, B.; Khan, M.A. Traditional ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants from coastal areas of Pakistan. J. Coast. Life. Med. 2014, 2, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, H.; Sher, Z.; Khan, Z.U. Medicinal plants from salt range Pind Dadan Khan, district Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 2157–2168. [Google Scholar]