Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain

Abstract

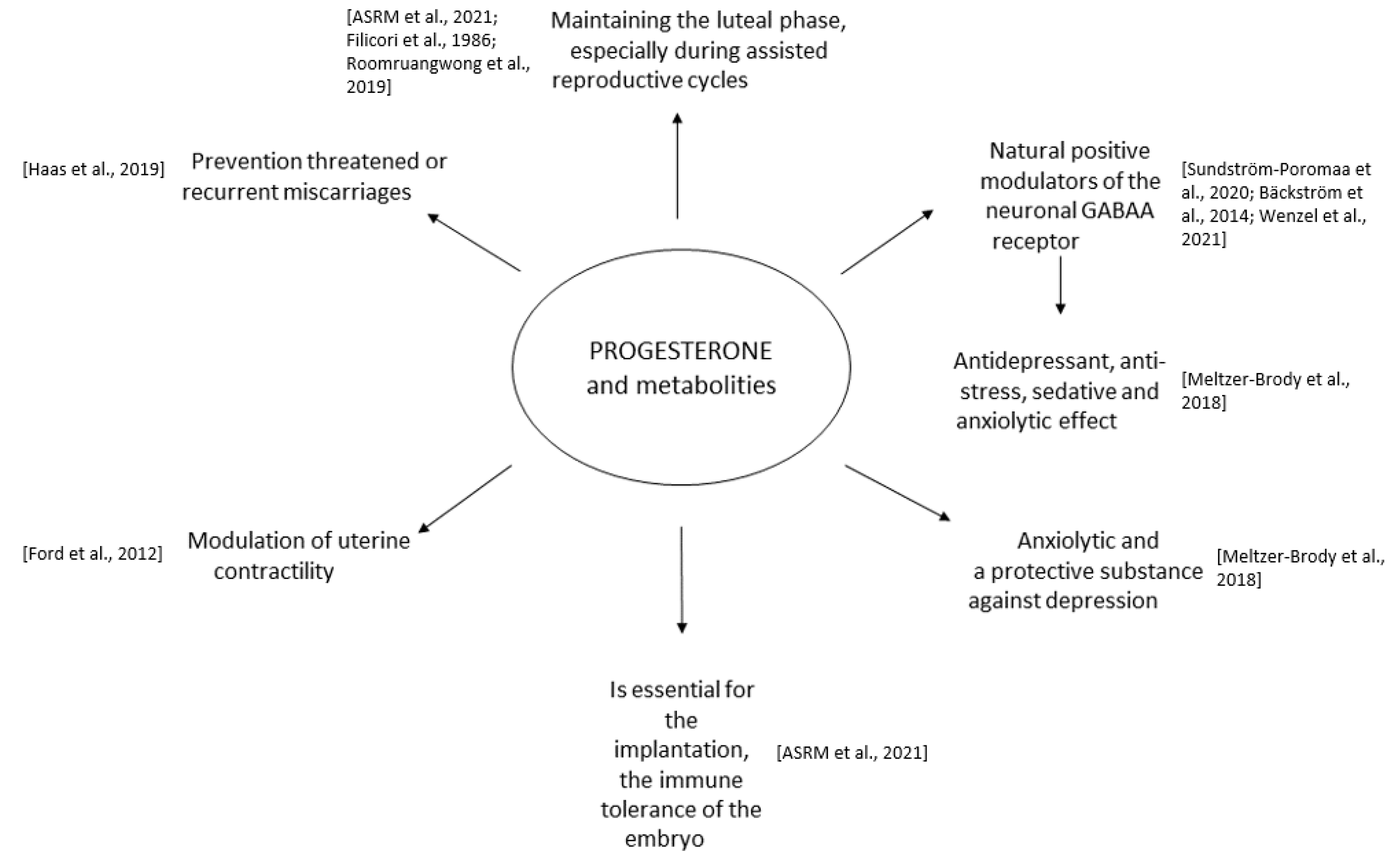

1. Introduction

2. Results

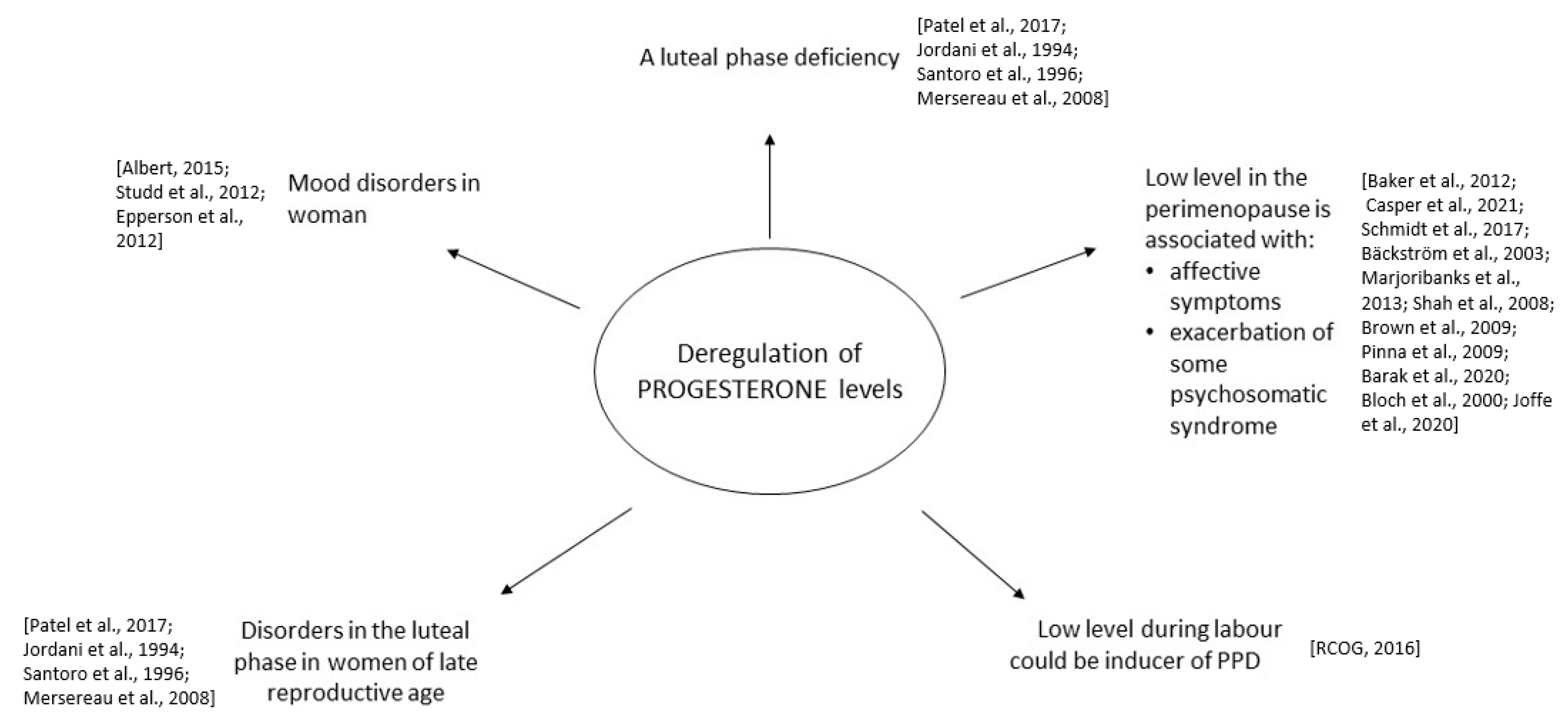

2.1. The Role of Progesterone and Its Metabolites in Luteal Phase Deficiency

2.2. The Role of Progesterone and Its Derivatives in the Regulation of Emotional Disorders in Women

2.3. Role of Progesterone and Allopregnanolone in Affective Disorders in The Perinatal Period

3. Future Perspectives

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuehner, C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faravelli, C.; Alessandra Scarpato, M.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C. Gender differences in depression and anxiety: The role of age. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accortt, E.E.; Freeman, M.P.; Allen, J.J. Women and major depressive disorder: Clinical perspectives on causal pathways. J. Womens Health 2008, 17, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreano, J.M.; Touroutoglou, A.; Dickerson, B.; Barrett, L.F. Hormonal Cycles, Brain Network Connectivity, and Windows of Vulnerability to Affective Disorder. Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemus, M.; Sarvaiya, N.; Neill Epperson, C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutzios, G.; Karalaki, M.; Zapanti, E. Common pathophysiological mechanisms involved in luteal phase deficiency and polycystic ovary syndrome. Impact on fertility. Endocrine 2013, 43, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Diagnosis and treatment of luteal phase deficiency: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Comasco, E.; Sumner, R.; Luders, E. Progesterone—Friend or foe? Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 59, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, T.; Bixo, M.; Johansson, M.; Nyberg, S.; Ossewaarde, L.; Ragagnin, G.; Savic, I.; Strömberg, J.; Timby, E.; van Broekhoven, F.; et al. Allopregnanolone and mood disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 113, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, E.S.; Pinna, G.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.; Bernabe, B.P.; Tallon, R.R.; Nagelli, U.; Davis, J.; Maki, P.M. Neuroactive steroids and depression in early pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 134, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B.; Szekeres-Barthó, J.; Kovács, G.L.; Sulyok, E.; Farkas, B.; Várnagy, Á.; Vértes, V.; Kovács, K.; Bódis, J. Key to Life: Physiological Role and Clinical Implications of Progesterone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filicori, M.; Santoro, N.; Merriam, G.R.; Crowley, W.F., Jr. Characterization of the physiological pattern of episodic gonadotropin secretion throughout the human menstrual cycle. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986, 62, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, O.; Lethaby, A.; Roberts, H.; Mol, B.W. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD003415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roomruangwong, C.; Carvalho, A.F.; Comhaire, F.; Maes, M. Lowered Plasma Steady-State Levels of Progesterone Combined with Declining Progesterone Levels During the Luteal Phase Predict Peri-Menstrual Syndrome and Its Major Subdomains. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, K. The Premenstrual Syndrome and Progesterone Therapy; William Heinemann Books: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, D.M.; Hathaway, T.J.; Ramsey, P.S. Progestogen for preventing miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage of unclear etiology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD003511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devall, A.J.; Papadopoulou, A.; Podesek, M.; Haas, D.M.; Price, M.J.; Coomarasamy, A.; Gallos, I.D. Progestogens for preventing miscarriage: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, CD013792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.E. Some newer aspects of the management of infertility. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1949, 141, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliep, K.C.; Mumford, S.L.; Hammoud, A.O.; Stanford, J.B.; Kissell, K.A.; Sjaarda, L.A.; Perkins, N.J.; Ahrens, K.A.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Mendola, P.; et al. Luteal phase deficiency in regularly menstruating women: Prevalence and overlap in identification based on clinical and biochemical diagnostic criteria. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E1007–E1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strott, C.A.; Cargille, C.M.; Ross, G.T.; Lipsett, M.B. The short luteal phase. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1970, 30, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, B.Y.; Betz, G. Altered luteinizing hormone pulse frequency in early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle with luteal phase defect patients in women. Fertil. Steril. 1993, 60, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweiger, U.; Laessle, R.G.; Tuschl, R.J.; Broocks, A.; Krusche, T.; Pirke, K.M. Decreased follicular phase gonadotropin secretion is associated with impaired estradiol and progesterone secretion during the follicular and luteal phases in normally menstruating women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1989, 68, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, A.B.; Mortola, J.F.; Girton, L.; Yen, S.S. Alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes in athletic women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1989, 68, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burney, R.O.; Talbi, S.; Hamilton, A.E.; Vo, K.C.; Nyegaard, M.; Nezhat, C.R.; Lessey, B.A.; Giudice, L.C. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 3814–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.G.; Rudnicki, M.; Yu, J.; Shu, Y.; Taylor, R.N. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: Origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obs. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Craig, K.; Clifton, D.K.; Soules, M.R. Luteal phase deficiency: The sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods in common clinical use. Fertil. Steril. 1994, 62, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.J.; Meyer, W.R.; Zaino, R.J.; Lessey, B.A.; Novotny, D.B.; Ireland, K.; Zeng, D.; Fritz, M. A critical analysis of the accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical utility of histologic endometrial dating in fertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, E.R.; Silva, S.; Barnhart, K.; Groben, P.A.; Richardson, M.S.; Robboy, S.J. NICHD National Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in the histological dating of the endometrium in fertile and infertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutifaris, C.; Myers, E.R.; Guzick, D.S.; Diamond, M.P.; Carson, S.A.; Legro, R.S.; McGovern, P.; Schlaff, W.; Carr, B.; Steinkampf, M.; et al. NICHD National Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network. Histological dating of timed endometrial biopsy tissue is not related to fertility status. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, N.; Brown, J.R.; Adel, T.; Skurnick, J.H. Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mersereau, J.E.; Evans, M.L.; Moore, D.H.; Liu, J.H.; Thomas, M.A.; Rebar, R.W.; Pennington, E.; Cedar, M.I. Luteal phase estrogen is decreased in regularly menstruating older women compared with a reference population of younger women. Menopause 2008, 15, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, J. Neuroactive Steroids and GABAergic Involvement in the Neuroendocrine Dysfunction Associated with Major Depressive Disorder and Postpartum Depression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, I. GABA-AR modulator for postpartum depression. Cell 2019, 176, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer-Brody, S.; Colquhoun, H.; Riesenberg, R.; Epperson, C.N.; Deligiannidis, K.M.; Rubinow, D.R.; Li, H.; Sankoh, A.J.; Clemson, C.; Schacterle, A.; et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: Two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2018, 392, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, R.D.; Thompson, R.F.; Foy, M.R.; Baudry, M.; Wang, J.; Finch, C.E.; Morgan, T.; Pike, C.; Mack, W.; Stanczyk, F. Progesterone receptors: Form and function in brain. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 29, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, C.J.; De Vries, G.J. Progestin receptor immunoreactivity within steroid-responsive vasopressin-immunoreactive cells in the male and female rat brain. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2002, 14, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, P.; Perez, J.; Barale, F.; Schettini, G.; Soares, J.C. GABAergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2003, 8, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.A.; Herd, M.B.; Gunn, B.G.; Lambert, J.J.; Belelli, D. Neurosteroid modulation of GABA(A) receptors: Molecular determinants and significance in health and disease. Neurochem. Int. 2007, 52, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingen, G.; van Broekhoven, F.; Verkes, R.J.; Petersson, K.M.; Backstrom, T.; Buitelaar, J.; Fernandez, G. How progesterone impairs memory for biologically salient stimuli in healthy young women. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 11416–11423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premenstrual Syndrome, Management (Green-Top Guideline No. 48). Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2016. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg48/ (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Cunningham, J.; Yonkers, K.A.; O’Brien, S.; Eriksson, E. Update on research and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziomkiewicz, A.; Pawlowski, B.; Ellison, P.T.; Lipson, S.F.; Thune, I.; Jasienska, G. Higher luteal progesterone is associated with low levels of premenstrual aggressive behavior and fatigue. Biol. Psychol. 2012, 91, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovick, T.A.; Guapo, V.G.; Anselmo-Franci, J.A.; Loureiro, C.M.; Faleiros, M.C.M.; Del Ben, C.M.; Brandão, M.L. A specific profile of luteal phase progesterone is associated with the development of premenstrual symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 75, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreen, L.; Nyberg, S.; Turkmen, S.; Wingen, G.; Fernández, G.; Bäckström, T. Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by GABA-A modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapkin, A.J.; Berman, S.M.; Mandelkern, M.A.; Silverman, D.H.S.; Morgan, M.; London, E.D. Neuroimaging evidence of cerebellar involvement in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerstein, L.; Spencer-Gardner, C.; Brown, J.B.; Smith, M.A.; Burrows, G.D. Premenstrual tension-hormonal profiles. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1984, 3, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, M.R.; Brush, M.G.; Taylor, R.W. Correlations between progesterone, oestradiol and aldosterone levels in the premenstrual syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 1981, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, E.; Sundblad Ch Lisjö, P.; Modigh, K.; Björn, A. Serum levels of androgens are higher in women with premenstrual irritability and dysphoria than in controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1992, 17, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redei, E.; Freeman, E.W. Daily plasma estradiol and progesterone levels over the menstrual cycle and their relation to premenstrual symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1995, 20, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailliot, M.T.; Hildebrandt, B.; Eckel, L.A.; Baumeister, R.F. A theory of limited metabolic energy and premenstrual syndrome symptoms: Increased metabolic demands during the luteal phase divert metabolic resources from and impair self-control. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.J.; O’Brien, P.M. Potential strategies to avoid progestogeninduced premenstrual disorders. Menopause Int. 2012, 18, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, R.F.; Yonkers, K.A. Treatment of Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder—UpToDate. Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/contents/treatment-of-premenstrual-syndrome-and-premenstrual-dysphoric (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Schmidt, P.J.; Martinez, P.E.; Nieman, L.K.; Koziol, D.E.; Thompson, K.D.; Schenkel, L.; Wakim, P.G.; Rubinow, D.R. Exposure to a change in ovarian steroid levels but not continuous stable levels triggers PMDD symptoms following ovarian suppression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, T.; Andreen, L.; Birzniece, V.; Björn, I.; Johansson, I.M.; Nordenstam-Haghjo, M.; Nyberg, S.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Wahlström, G.; Wang, M.; et al. The role of hormones and hormonal treatments in premenstrual syndrome. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, J.; Brown, J.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Wyatt, K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD001396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.R.; Jones, J.B.; Aperi, J.; Shemtov, R.; Karne, A.; Borenstein, J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for pre-menstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A meta-analysis. Obs. Gynecol. 2008, 111, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Marjoribanks, J.; Wyatt, K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2, CD001396. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, G.; Costa, E.; Guidotti, A. SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009, 9, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, Y.; Glue, P. Progesterone loading as a strategy for treating postpartum depression. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 35, e2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, M.; Schmidt, P.J.; Danaceau, M.; Murphy, J.; Nieman, L.; Rubinow, D.R. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.; de Wit, A.; Coborn, J.; Crawford, S.; Freeman, M.; Wiley, A.; Athappilly, G.; Kim, S.; Sullivan, K.; Cohen, L.; et al. Impact of Estradiol Variability and Progesterone on Mood in Perimenopausal Women with Depressive Symptoms. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e642–e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanes, S.J.; Colquhoun, H.; Doherty, J.; Raines, S.; Hoffmann, E.; Rubinow, D.R.; Meltzer-Brody, S. Open-label, proof-of-concept study of brexanolone in the treatment of severe postpartum depression. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 32, e2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsouni, E.; Fisher, P.M.; Dubol, M.; Hustad, S.; Lanzenberger, R.; Frokjaer, V.G.; Wikström, J.; Comasco, E. Brain reactivity during aggressive response in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder treated with a selective progesterone receptor modulator. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixo, M.; Ekberg, K.; Poromaa, I.S.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Jonasson, A.F.; Andréen, L.; Timby, E.; Wulff, M.; Ehrenborg, A.; Bäckström, T. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with the GABA-A receptor modulating steroid antagonist Sepranolone (UC1010)-A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 80, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, T.; Ekberg, K.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Bixo, M.; Epperson, C.N.; Briggs, P.; Panay, N.; O’Brien, S. A randomized, double-blind study on efficacy and safety of sepranolone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 133, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkery, A.; Leader, L.D.; Cooke, E.; VandenBerg, A. Review of Allopregnanolone Agonist Therapy for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studd, J.; Nappi, R.E. Reproductive depression. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epperson, C.N.; Steiner, M.; Hartlage, S.A.; Eriksson, E.; Schmidt, P.; Jones, I.; Yonkers, K.A. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for a new category for DSM. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldzic-Zivanovic, N.; Seitz, P.K.; Watson, C.S.; Cunningham, K.A.; Thomas, M.L. Intracellular signaling involved in estrogen regulation of serotonin reuptake. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 226, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudevinge, M.S.; O’Connor, P.J. A review of physical activity patterns in pregnant women and their relationship to psychological health. Sport. Med. 2006, 36, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Hao, J.; Tao, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, R. Pregnancy loss and anxiety and depression during subsequent pregnancies: Data from the C-ABC study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 166, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, L.; Zinga, D.; Phillips, S.D. Update on the treatment of depression during pregnancy. Therapy 2006, 3, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariante, C.; Conroy, S.; Dazzan, P.; Howard, L.; Pawlby, S.; Seneviratne, T. Perinatal Psychiatry: The Legacy of Channi Kumar; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, M.; Carballedo, A.; O’Keane, V. Perinatal depression and psychosis: An update. BJPsych Adv. 2015, 21, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, M.M.; Mott, S.L.; Pearlstein, T.; Stuart, S.; Zlotnick, C.; O’hara, M.W. Examination of premenstrual symptoms as a risk factor for depression in postpartum women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013, 16, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoner, R.; Camilleri, V.; Calleja-Agius, J.; Schembri-Wismayer, P. The cytokine-hormone axis—The link between premenstrual syndrome and postpartum depression. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2017, 33, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, J.; Ogbo, F.A.; Hendry, A.; Noble, J.; Page, A. The Impact of Antenatal Depression on Perinatal Outcomes in Australian Women. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.E.; Robertson, E.; Phil, M.; Dennis, C.L.; Grace, S.L.; Wallington, T. Postpartum Depression: Literature Review of Risk Factors and Interventions; Toronto Public Health; University Health Network Women’s Health Program: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos, A.L.; Dubin-Rhodin, A.; Sackett, J.C.; Dixon, T.A.; Weller, R.A.; Weller, E.B. The impact of mood disorders and their treatment on the pregnant woman, the fetus, and the infant. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2010, 12, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, C.V.N.; da Silveira, M.F.; Bassani, D.G.; Netsi, E.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Barros, F.C.; Stein, A. Antenatal depressive symptoms among pregnant women: Evidence from Southern Brazilian population-based cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 209, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert Evans, S.E.; Ross, L.E.; Sellers, E.M.; Purdy, R.H.; Romach, M.K. 3α-reducted neuroactive steroids and their precursors during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2005, 21, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, I.S.; Tanner Stapleton, L.R.; Guardino, C.M.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: Systematic review and call for integration. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.; Lovett, L.; Newcombe, R.G.; Read, G.F.; Walker, R.; Riad-Fahmy, D. Maternity blues and major endocrine changes: Cardiff puerperal mood and hormone study II. BMJ 1994, 1994, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, L.M.; Gispen, F.; Sanyal, A.; Yenokyan, G.; Meilman, S.; Payne, J.L. Lower allopregnanolone during pregnancy predicts postpartum depression: An exploratory study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 79, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, J.G.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; McCleary, C.A.; Bluestein, B.W.; Buckwalter, D.K.; Rankin, K.P.; Chang, L.; Murphy Goodwin, T. Pregnancy, the postpartum, and steroid hormones: Effects on cognition and mood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1999, 24, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel, E.C.; Craft, R.M. Ovarian hormone withdrawal-induced “depression” in female rats. Physiol. Behav. 1999, 83, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, S.; Segi-Nishida, E.; Newton, S.S.; Duman, R.S. A postpartum model in rat: Behavioral and gene expression changes induced by ovarian steroid deprivation. Biol. Psychiatr. 2008, 64, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, A.; Schleyer, M.; Spingler, H.; Albert, P.; Knoche, M.; Fritze, J.; Lanczik, M. Postpartum blues: Relationship between not-protein bound steroid hormones in plasma and postpartum mood changes. J. Affect. Disord. 1994, 30, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, C.; Akerud, H.; Skalkidou, A.; Backstrom, T.; Sundstrom-Poromaa, I. Low serum allopregnanolone is associated with symptoms of depression in late pregnancy. Neuropsychobiology 2014, 69, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligiannidis, K.M.; Sikoglu, E.M.; Shaffer, S.A.; Frederick, B.; Svenson, A.E.; Kopoyan, A.; Kosma, C.A.; Rothschild, A.J.; Moore, C.M. GABAergic neuroactive steroids and resting-state functional connectivity in postpartum depression: A preliminary study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, J.; Mody, I. GABA-AR plasticity during pregnancy: Relevance to postpartum depression. Neuron 2008, 59, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, E.; Strohle, A.; Spalletta, G.; di Michele, M.F.; Hermann, B.; Holsboer, F.; Pasini, A.; Rupprecht, R. Effects of antidepressant treatment on neuroactive steroids in major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, V.; Sheline, Y.; Davis, J.M.; Rasmusson, A.; Uzunov, D.P.; Costa, E.; Guidotti, A. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3239–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, G.; Costa, E.; Guidotti, A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology 2006, 186, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schule, C.; Nothdurfter, C.; Rupprecht, R. The role of allopregnanolone in depression and anxiety. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 113, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padberg, F.; di Michele, F.; Zwanzger, P.; Romeo, E.; Bernardi, G.; Schule, C.; Baghai, T.C.; Ella, R.; Pasini, A.; Rupprecht, R. Plasma concentrations of neuroactive steroids before and after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, R.E.; Petraglia, F.; Luisi, S.; Polatti, F.; Farina, C.; Genazzani, A.R. Serum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum “blues”. Obs. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Le Melledo, J.M.; Van Driel, M.; Coupland, N.J.; Lott, P.; Jhangri, G.S. Response to flumazenil in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Publication Year | Population Size | Type of Study | Hormone Used | Objectives | Primary Outcomes | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford et. al. [13] | 2012 | 280 | Systematic review | Progesterone | The objectives were to determine if progesterone has been found to be an effective treatment for all or some premenstrual symptoms and if adverse events associated with this treatment have been reported. | The trials did not show that progesterone is an effective treatment for PMS or that it is not. | No statistically significant difference |

| Roomruangwong et al. [14] | 2019 | 41 | Observational study | Quantitative determination of oestradiol and progesterone. | To examine associations between levels of progesterone and oestradiol during the menstrual cycle and PMS, considering different diagnostic criteria for PMS. | Lowered steady-state levels of progesterone, when averaged over the menstrual cycle, together with declining progesterone levels during the luteal phase, predict the severity of peri-menstrual symptoms. | >0.8 |

| Haas et al. [16] | 2018 | 2556 | Systematic review | Progestogen | To assess the efficacy and safety of progestogens as a preventative therapy against recurrent miscarriage. | The meta-analysis of all women suggests that there is probably a reduction in the number of miscarriages for women given progestogen supplementation compared to placebo/controls (average risk ratio (RR) 0.69, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 0.92, 11 trials, 2359 women, moderate-quality evidence). | Average risk ratio (RR) 0.69, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 0.92, 11 trials, 2359 women, moderate-quality evidence. |

| Meltzer-Brody et al. [34] | 2018 | 375 | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trials | Breksanolon patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive a single intravenous injection of either brexanolone 90 μg/kg per h (BRX90), brexanolone 60 μg/kg per h (BRX60), or matching placebo for 60 h. | Assessed brexanolone injection (formerly SAGE-547 injection), a positive allosteric modulator of γ-aminobutyric-acid type A (GABAA) receptors, for the treatment of moderate to severe postpartum depression. | Administration of brexanolone injection for postpartum depression resulted in significant and clinically meaningful reductions in the HAM-D total score at 60 h compared with placebo, with a rapid onset of action and durable treatment response during the study period. | Statistically significant |

| Ziomkiewicz et al. [42] | 2012 | 122 | Observational study | Saliva samples were assayed for progesterone concentrations. | Assayed for progesterone concentrations and mood intensity scores were used to calculate behavioral indices. | Women with low aggression/irritability and fatigue had consistently higher progesterone levels during the luteal phase than women with high aggression/irritability and fatigue. Additionally, aggression/irritability and fatigue correlated negatively with maximal progesterone value during the luteal phase. Results demonstrated a negative effect of low progesterone levels on premenstrual mood symptoms, such as aggressive behavior and fatigue in healthy reproductive-age women. | Statistically significant |

| Lovick et al. [43] | 2017 | 46 | Case control study | Progesterone | Evaluated not only the absolute concentrations of progesterone but also the kinetics of the change in progesterone concentration in relation to the development of premenstrual symptoms during the last 10 days of the luteal phase | In participants who developed symptoms of premenstrual distress, the daily saliva progesterone concentration remained stable during most of the mid-late luteal phase, before declining sharply during the last 3 days prior to the onset of menstruation. In contrast, progesterone concentration in asymptomatic women underwent a gradual decline over the last 8 days prior to menstruation. Neither the maximum nor minimum concentrations of progesterone in the two groups were related to the appearance or severity of premenstrual symptoms. | Statistically significant |

| Rapkin et al. [45] | 2011 | 12 women with PMDD and 12 healthy women | Case control study | Blood samples were taken before each session for an assay of plasma estradiol and progesterone concentrations. | Positron emission tomography with [(18)F] fluorodeoxyglucose and self-report questionnaires to assess cerebral glucose metabolism. The primary biological end point was incorporated into regional cerebral radioactivity (scaled to the global mean) as an index of glucose metabolism. Relationships between regional brain activity and mood ratings were assessed. | There were no group differences in hormone levels in either the follicular or late luteal phase, but the groups differed in the effect of menstrual phase on cerebellar activity. | Women with PMDD but not comparison subjects showed an increase in cerebellar activity (particularly in the right cerebellar vermis) from the follicular phase to the late luteal phase (p = 0.003). In the PMDD group, this increase in cerebellar activity was correlated with worsening of mood (p = 0.018). |

| Redei et al. [49] | 1995 | 10 women with confirmed PMS and 8 asymptomatic women | Case control study | Plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone were measured daily | Assessment of plasma ACTH levels in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) compared with asymptomatic controls. | Both estradiol and progesterone levels were consistently, but not significantly, higher throughout the cycle in PMS subjects compared with controls. From the follicular to the early luteal phase, estradiol levels were significantly higher in a previously defined PMS subgroup 2 with more severe symptoms throughout the cycle compared with both the less severe PMS subgroup 1 and controls. Progesterone levels were significantly and positively correlated with PMS symptoms along the entire menstrual cycle, preceding the symptoms by 5–7 days. These preliminary results provide support for the hypothesis that the presence of progesterone at early luteal phase levels is required for PMS symptoms to occur. | Statistically significant |

| Kaltsouni. et al. [63] | 2021 | 35 women with PMDD | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled | Determine the levels of estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, and cortisol. | Investigate the neural correlates of reactive aggression during the premenstrual phase in women with PMDD, randomized to a selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM) or placebo. | The findings contribute to defining the role of progesterone in PMDD symptomatology, suggesting a beneficial effect of progesterone receptor antagonism, and consequent anovulation, on top- down emotion regulation, i.e., greater fronto-cingulate activity in response to provocation stimuli. | Statistically significant |

| Bixo et al. [64] | 2017 | 26 healthy women in a pharmacokinetic phase I study, and 126 women with PMDD in a phase II study. | Explorative randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. | Subjects were randomized to treatment with UC1010 (10 or 16 mg) subcutaneously every second day during the luteal phase or placebo during one menstrual cycle. | Test whether inhibition of allopregnanolone by treatment with the GABAA modulating steroid antagonist (GAMSA) Sepranolone (UC1010) during the premenstrual phase could reduce symptoms of the premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). | This explorative study indicates promising results for UC1010 as a potential treatment for PMDD. The effect size was comparable to that of SSRIs and drospirenone-containing oral contraceptives. UC1010 was well tolerated and deemed safe. | Statistically significant |

| Bäckström et al. [65] | 2021 | 206 | A randomized, double-blind study | Treat PMDD patients with the GABAA receptor modulating steroid antagonist, sepranolone (isoallopregnanolone). Patients were administered sepranolone subcutaneously every 48 h during the 14 premenstrual days of three consecutive menstrual cycles. | Test the hypothesis that sepranolone is more effective than a placebo in reducing PMDD symptoms, presumably through sepranolone-induced inhibition or blockade of allopregnanolone action at the GABAA receptor in women with PMDD (Bäckström et al., 2011). | The results indicate that there is an attenuating effect by sepranolone on the symptoms, impairment, and distress in women with PMDD, especially at the 10 mg dosage. Sepranolone was well tolerated, and no safety concerns were identified. | Statistically significant |

| Bloch et al. [60] | 2000 | Eight women with and eight without a history of postpartum depression | Cross-sectional study | Estradiol and progesterone | Investigated the possible role of changes in gonadal steroid levels in postpartum depression by simulating two hormonal conditions related to pregnancy and parturition in euthymic women with and without a history of postpartum depression. | The data provide direct evidence in support of the involvement of the reproductive hormones, estrogen and progesterone, in the development of postpartum depression in a subgroup of women. Further, they suggest that women with a history of postpartum depression are differentially sensitive to the mood-destabilizing effects of gonadal steroids. | Statistically significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stefaniak, M.; Dmoch-Gajzlerska, E.; Jankowska, K.; Rogowski, A.; Kajdy, A.; Maksym, R.B. Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16040520

Stefaniak M, Dmoch-Gajzlerska E, Jankowska K, Rogowski A, Kajdy A, Maksym RB. Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain. Pharmaceuticals. 2023; 16(4):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16040520

Chicago/Turabian StyleStefaniak, Małgorzata, Ewa Dmoch-Gajzlerska, Katarzyna Jankowska, Artur Rogowski, Anna Kajdy, and Radosław B. Maksym. 2023. "Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain" Pharmaceuticals 16, no. 4: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16040520

APA StyleStefaniak, M., Dmoch-Gajzlerska, E., Jankowska, K., Rogowski, A., Kajdy, A., & Maksym, R. B. (2023). Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain. Pharmaceuticals, 16(4), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16040520