Evaluation of Different Controllers for Sensing-Based Movement Intention Estimation and Safe Tracking in a Simulated LSTM Network-Based Elbow Exoskeleton Robot

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Preprocessing Analysis

2.4. Deep Learning Regression

2.5. Dynamic Model of Elbow Robot

2.6. Controller

2.6.1. PID Controller

2.6.2. Impedance Controller

2.6.3. Sliding Mode Controller

2.6.4. Controller Parameters

2.7. Evaluation Analysis

2.7.1. Deep Learning Evaluation

2.7.2. Controller Evaluation

3. Results

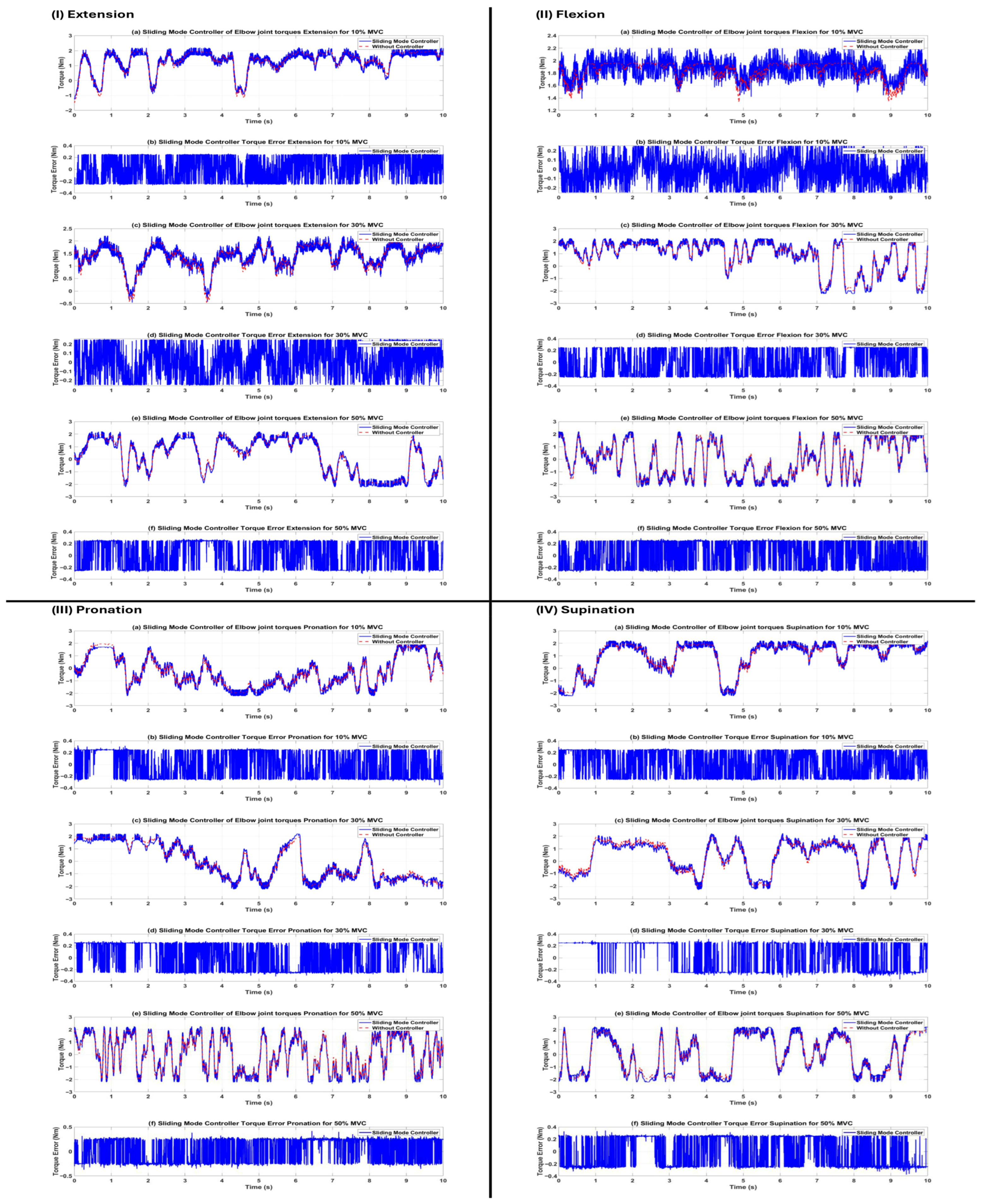

- Sliding Mode Controller: Attained the minimal RMSE (0.129–0.238 Nm) and EST values across all motions and levels of exertion. R2 remained consistently high (0.897–0.975), with correlation values above 0.95 in 11 of 12 circumstances. These findings validate the established resilience of SMC to model errors, nonlinear muscle dynamics, and the noise intrinsic to biological signals.

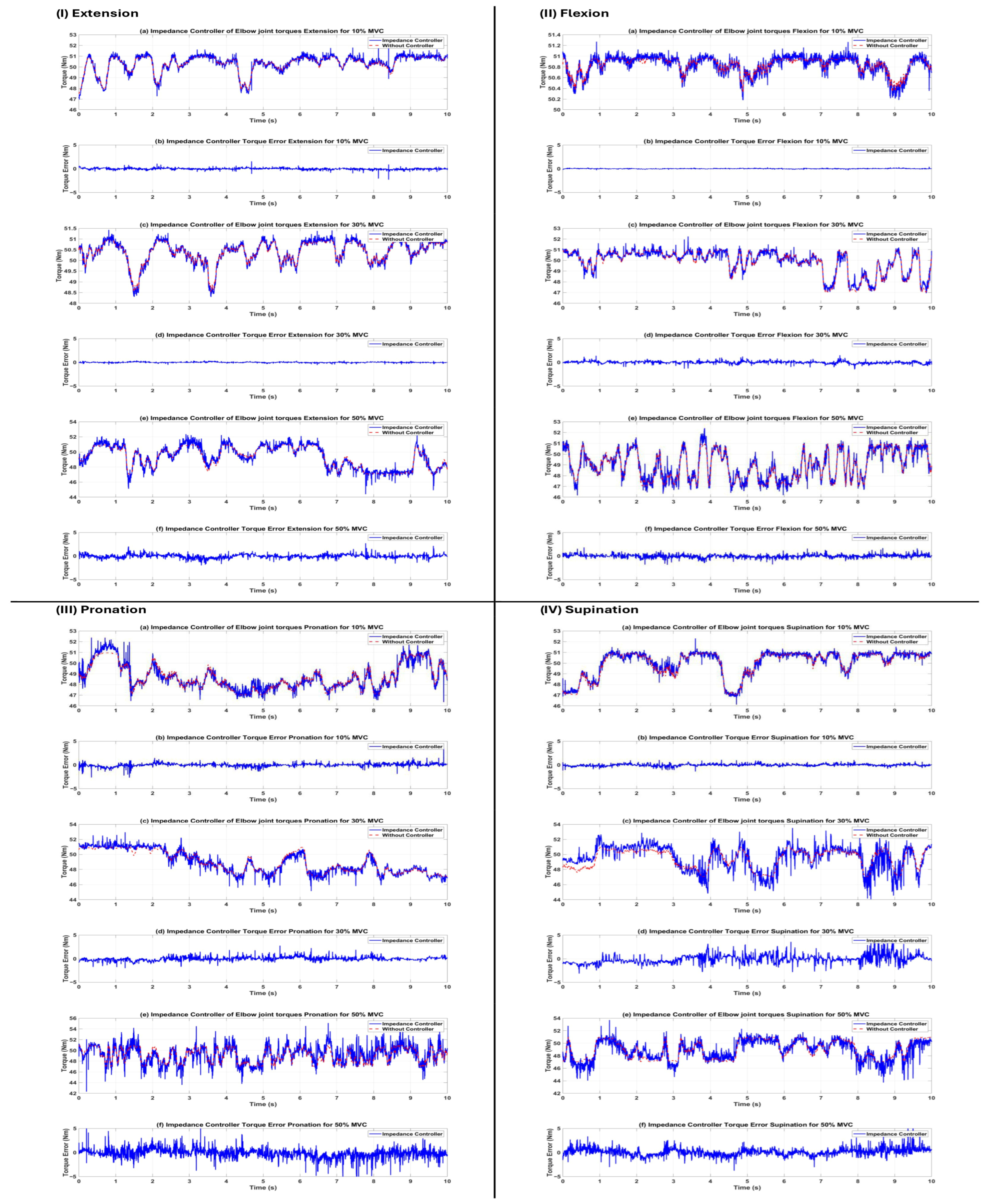

- Impedance Controller: Demonstrated superior performance, particularly in flexion and extension activities (RMSE 0.055–0.345 Nm, R2 0.939–0.971), leveraging adjustable rigidity () and damping () that effectively adapt to contact forces. Performance exhibited a modest decline in pronation/supination at elevated effort levels (R2 0.579–0.794 at 30–50% MVC) attributable to the reduced torsional stiffness of forearm rotation motions.

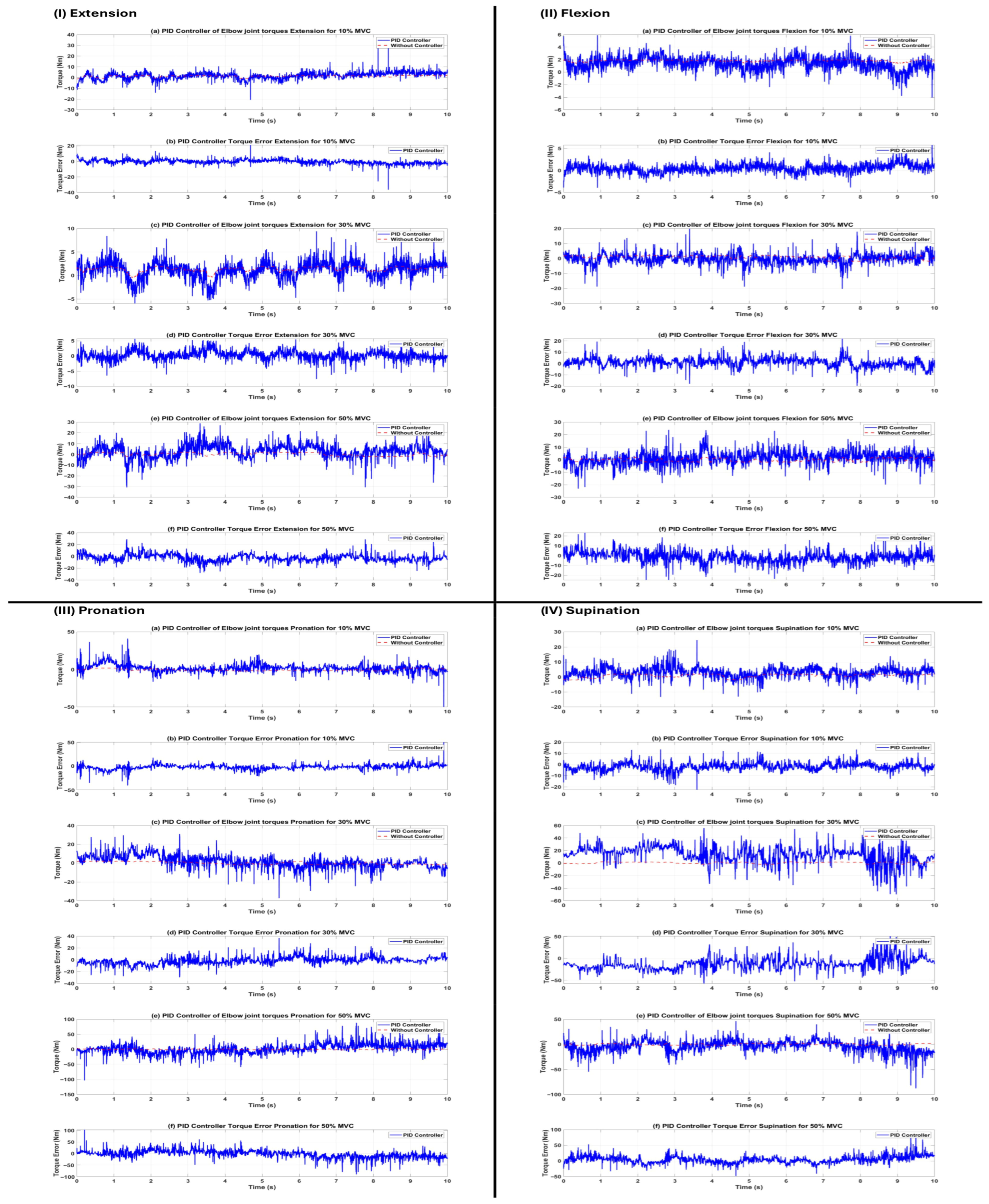

- PID Controller: Generated significant tracking errors under various settings (RMSE reaching 17.24 Nm, with negative R2 values in many instances), demonstrating inadequate resilience to the highly nonlinear and time-varying dynamics imposed by EMG-driven reference trajectories. The fixed-gain configuration proved insufficient to appropriately compensate for quick fluctuations in required torque and signal noise.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nizamis, K.; Athanasiou, A.; Almpani, S.; Dimitrousis, C.; Astaras, A. Converging robotic technologies in targeted neural rehabilitation: A review of emerging solutions and challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoni, P. Rehabilitation technologies for sensory-motor-cognitive impairments. In Cerebral Palsy: A Practical Guide for Rehabilitation Professionals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 461–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, F.; Gasperini, G.; Cannaviello, G.; Guanziroli, E. Exoskeleton and end-effector robots for upper and lower limbs rehabilitation: Narrative review. PM&R 2018, 10, S174–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethichandra, D.; Piyathilaka, L.; Sul, J.-H.; Izhar, U.; Samarasinghe, R.; Arachchige, S.D.; de Silva, L.C. Passive and active exoskeleton solutions: Sensors, actuators, applications, and recent trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, E.; Slayton, J.; Tejeda-Godinez, G.; Carney, E.; Cruz, K.; Exley, T.; Jafari, A. A review of rehabilitative and assistive technologies for upper-body exoskeletal devices. Actuators 2023, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Teo, H.H.; King, Y.J. Towards Intelligent Human-Robot Interaction for Upper Limb Rehabilitation: A Review of Emerging Modalities and Strategies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 185513–185532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, D.M.; Shehata, O.M.; Morgan, E.I.; Arrichiello, F. A Comprehensive Review of Control Challenges and Methods in End-Effector Upper-Limb Rehabilitation Robots. Robotics 2024, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huo, W.; Xu, W.; Mohammed, S.; Amirat, Y. Control of upper-limb power-assist exoskeleton using a human-robot interface based on motion intention recognition. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2015, 12, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoji, K.; Soleimani, M.; Moshayedi, A.J. A Comprehensive Review of Electromyography in Rehabilitation: Detecting Interrupted Wrist and Hand Movements with a Robotic Arm Approach. EAI Trans. AI Robot. 2024, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolandino, G.; Zangrandi, C.; Vieira, T.; Cerone, G.L.; Andrews, B.; FitzGerald, J.J. HDE-Array: Development and validation of a new dry electrode array design to acquire HD-sEMG for hand position estimation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 4004–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, L.; Wang, J.; Pan, M.; Yi, J.; Cheng, N.; Liu, T. A novel exoskeleton neuromuscular interface based on motor unit action potential model using high-density sEMG. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 4012112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanini, C.; Alhanai, T.; Shamout, F.E.; Atashzar, S.F. The Role of Functional Muscle Networks in Improving Hand Gesture Perception for Human-Machine Interfaces. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.02547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Harrach, M.; Carriou, V.; Boudaoud, S.; Laforet, J.; Marin, F. Analysis of the sEMG/force relationship using HD-sEMG technique and data fusion: A simulation study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 83, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Xu, X. Review of sEMG for Exoskeleton Robots: Motion Intention Recognition Techniques and Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, T.A. EMG Control of an Upper-Limb Rehabilitation Exoskeleton for SCI Affected Users. Master’s Thesis, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Falzarano, V. A Robot-Aided Evaluation of the Biomechanical Impedance of the Wrist as an Assessment Tool of Spasticity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Genova, Genova, Italy, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14242/66750 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Babaiasl, M.; Goldar, S.N.; Barhaghtalab, M.H.; Meigoli, V. Sliding mode control of an exoskeleton robot for use in upper-limb rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2015 3rd RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICROM), Tehran, Iran, 7–9 October 2015; pp. 694–701. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Trinh, V.C.; Le, T.D. An adaptive fast terminal sliding mode controller of exercise-assisted robotic arm for elbow joint rehabilitation featuring pneumatic artificial muscle actuator. Actuators 2020, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, P.; Li, X.; Tavakoli, M. Emg-based intention detection using deep learning for shared control in upper-limb assistive exoskeletons. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 2023, 9, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Garg, N.P.; Gao, R.; Yuan, M.; Noronha, B.; Ang, W.T.; Accoto, D. Learning-based motion-intention prediction for end-point control of upper-limb-assistive robots. Sensors 2023, 23, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Qi, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. Deep neural network approach in EMG-based force estimation for human–robot interaction. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, M.-S.; Woo, J.-H.; Sahithi, K.K.; Kim, S.-H. Continuous intention prediction of lifting motions using EMG-based CNN-LSTM. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42453–42464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivieso Caraguay, Á.L.; Vásconez, J.P.; Barona López, L.I.; Benalcázar, M.E. Recognition of hand gestures based on EMG signals with deep and double-deep q-networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Gao, L.; Cao, H.; Li, Z. sEMG-upper limb interaction force estimation framework based on residual network and bidirectional long short-term memory network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Gang, S.; Guan, C. FCIHMRT: Feature cross-layer interaction hybrid method based on Res2Net and transformer for remote sensing scene classification. Electronics 2023, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeriaski, F.; Mohammadian, M. Enhancing Upper Limb Exoskeletons Using Sensor-Based Deep Learning Torque Prediction and PID Control. Sensors 2025, 25, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, S.; Herath, H.; Yasakethu, S.; Fernando, D.; Madusanka, N.; Yi, M.; Lee, B.-I. Long Short-Term Memory-Enabled Electromyography-Controlled Adaptive Wearable Robotic Exoskeleton for Upper Arm Rehabilitation. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, D.; Schmermbeck, K.; Vazquez-Pufleau, M.; Ferscha, A. Intention prediction for active upper-limb exoskeletons in industrial applications: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2025, 25, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Di Natali, C.; Sposito, M.; Caldwell, D.G.; Ortiz, J. Elbow-sideWINDER (Elbow-side Wearable INDustrial Ergonomic Robot): Design, control, and validation of a novel elbow exoskeleton. Front. Neurorob. 2023, 17, 1168213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Saad, M.; Kenné, J.-P.; Archambault, P. Exoskeleton robot for rehabilitation of elbow and forearm movements. In Proceedings of the 18th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED’10), Marrakech, Morocco, 23–25 June 2010; pp. 1567–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello, N.; Lenzi, T.; Roccella, S.; De Rossi, S.M.M.; Cattin, E.; Giovacchini, F.; Vecchi, F.; Carrozza, M.C. NEUROExos: A powered elbow exoskeleton for physical rehabilitation. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2012, 29, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi, K.; Kariya, S.; Watanabe, K.; Izumi, K.; Fukuda, T. An exoskeletal robot for human elbow motion support-sensor fusion, adaptation, and control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B Cybern. 2001, 31, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copaci, D.; Martin, F.; Moreno, L.; Blanco, D. SMA based elbow exoskeleton for rehabilitation therapy and patient evaluation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 31473–31484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copaci, D.; Cano, E.; Moreno, L.; Blanco, D. New design of a soft robotics wearable elbow exoskeleton based on shape memory alloy wire actuators. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2017, 2017, 1605101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.H.; Kittel-Ouimet, T.; Saad, M.; Kenné, J.-P.; Archambault, P.S. Robot assisted rehabilitation for elbow and forearm movements. Int. J. Biomechatron. Biomed. Rob. 2011, 1, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Martínez, M.; Serna, L.Y.; Jordanic, M.; Marateb, H.R.; Merletti, R.; Mañanas, M.Á. High-density surface electromyography signals during isometric contractions of elbow muscles of healthy humans. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Khundrakpam, B.; Vaughan, T. Effects of Electrode Position Targeting in Noninvasive Electromyography Technologies for Finger and Hand Movement Prediction. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2023, 43, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Singh, M. Time-domain feature and ensemble model based classification of emg signals for hand gesture recognition. Res. Sq. 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, D.; Doğru, S.C. Utilization of Electromyographic Signal Classification for Predicting Hand Gestures and Grasping Forces Through Artificial Neural Networks. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. Part A Eng. Innov. 2025, 12, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, J.; Abdullah, A.R.; Saad, N.M. Classification of hand movements based on discrete wavelet transform and enhanced feature extraction. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Zhou, Z.-W. Comparison of Image Fusion based on DCT-STD and DWT-STD. In Proceedings of the International Multiconference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, China, 14–16 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nabian, M.; Nouhi, A.; Yin, Y.; Ostadabbas, S. A biosignal-specific processing tool for machine learning and pattern recognition. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Healthcare Innovations and Point of Care Technologies (HI-POCT), Bethesda, MD, USA, 6–8 November 2017; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P.; Chowdhury, E.; Gedam, V.; Kumar, C.S.; Mahadevappa, M. Classification of EMG Signals Between Healthy and Stroke Subjects in Upper Limb Muscle Activities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing and Computer Vision (SIPCOV-2023), Silchar, India, 30–31 March 2023; pp. 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; O’Sullivan, L.; Gallwey, T.J. Estimating upper limb discomfort level due to intermittent isometric pronation torque with various combinations of elbow angles, forearm rotation angles, force and frequency with upper arm at 90 abduction. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2007, 37, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Gallwey, T.J. Forearm torque strengths and discomfort profiles in pronation and supination. Ergonomics 2005, 48, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Nambu, I.; Maruyama, Y.; Wada, Y. Sliding-window normalization to improve the performance of machine-learning models for real-time motion prediction using electromyography. Sensors 2022, 22, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S. Introduction to Sequence Learning Models: RNN, LSTM, GRU; Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2021; p. 37988518. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Moncada, C.A.; Pérez-Vidal, A.F.; Ortiz-Torres, G.; Sorcia-Vázquez, F.D.J.; Rumbo-Morales, J.Y.; Cervantes, J.-A.; Hernández-Magaña, C.E.; Figueroa-Jiménez, M.D.; Brizuela-Mendoza, J.A.; Rodríguez-Cerda, J.C. Development and Analysis of an Exoskeleton for Upper Limb Elbow Joint Rehabilitation Using EEG Signals. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiloyannis, M.; Chiaradia, D.; Frisoli, A.; Masia, L. Physiological and kinematic effects of a soft exosuit on arm movements. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Islam, M.R.; Brahmi, B.; Rahman, M.H. Robustness and tracking performance evaluation of PID motion control of 7 DoF anthropomorphic exoskeleton robot assisted upper limb rehabilitation. Sensors 2022, 22, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N. Impedance control: An approach to manipulation: Part II—Implementation. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Contr. 1985, 107, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, D.; Qian, W.; Xiao, X.; Guo, Z. Modeling and control of a cable-driven rotary series elastic actuator for an upper limb rehabilitation robot. Front. Neurorob. 2020, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajoudani, A. Transferring Human Impedance Regulation Skills to Robots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C. Cartesian Impedance Control of Redundant and Flexible-Joint Robots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; He, W.; Su, C.-Y. Adaptive impedance control for an upper limb robotic exoskeleton using biological signals. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 64, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.D.; Pereira, T.F.; Leithardt, V.R.; Seman, L.O.; Zeferino, C.A. Hybrid impedance-admittance control for upper limb exoskeleton using electromyography. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Sliding mode control of manipulator based on improved reaching law and sliding surface. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaa, M.Y.; Barambones, O.; Bencherif, A.; Rougab, I. An Adaptive Control Strategy with Switching Gain and Forgetting Factor for a Robotic Arm Manipulator. Machines 2025, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harary, M. Combinatorial optimization of the coefficient of determination. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, S.; Bu, D.; Wang, H.; Kawanishi, M. Subject-independent estimation of continuous movements using CNN-LSTM for a home-based upper limb rehabilitation system. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 6403–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Metric | Equation | Evaluation Metric | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square (RMS) [37] | Simple Square Integral (SSI) [37] | ||

| Waveform Length (WL) [37] | Mean Absolute Value (MAV) [37] | ||

| Zero Crossing (ZC) [37] | Modified Mean Absolute Value Type 1 (MAV1) [38] | ||

| Difference in Absolute Standard Deviation Value (DASDV) [39] | Average Amplitude change (AAC) [40] | ||

| Enhanced Wavelength (EWL) [40] | Enhanced Mean absolute value (EMAV) [40] | ||

| Standard Deviation (STD) [41] | Log Detector (LD) [42] | ||

| Variance in EMG (VAR) [43] |

| 10% MVC | 30% MVC | 50% MVC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | 140 | 150 | 160 |

| Extension | 145 | 155 | 165 |

| Supination | 75 | 80 | 85 |

| Pronation | 78 | 83 | 88 |

| LSTM Units | Dropout Rate | Batch Norm | FC Layers | Validation RMSE (Nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 0.2 | No | 2 | 0.892 |

| 64 | 0.3 | Yes | 3 | 0.785 |

| 128 | 0.2 | Yes | 2 | 0.712 |

| 128 | 0.3 | Yes | 3 | 0.658 |

| 128 | 0.5 | Yes | 3 | 0.694 |

| 256 | 0.3 | Yes | 3 | 0.703 |

| 128 (bidirectional) | 0.3 | Yes | 3 | 0.721 |

| Controller | Parameter | Value | Tuning Criterion/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PID | 15 | Minimized RMSE on validation tasks; high for fast response, moderate to suppress overshoot, small to reduce steady-state error without instability | |

| Ki | 8 | ||

| Kd | 2 | ||

| Impedance | Stiffness (Nm/rad) | 1 | Balanced compliance and tracking accuracy; lower K for higher transparency in low-effort tasks, adjusted to avoid excessive deviation in high-effort scenarios |

| Damping (Nm·s/rad) | 0.5 | ||

| Sliding Mode | Sliding surface gain | 1 | Robustness to disturbances; high for fast convergence, boundary layer thickness to minimize chattering while maintaining RMSE ≈ 0.21 Nm |

| Switching gain | 0.25 | ||

| Boundary layer thickness | 0.1 |

| Evaluation Metric | Equation | Evaluation Metric | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation of Error (STD) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | ||

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | Paired t-test | ||

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) |

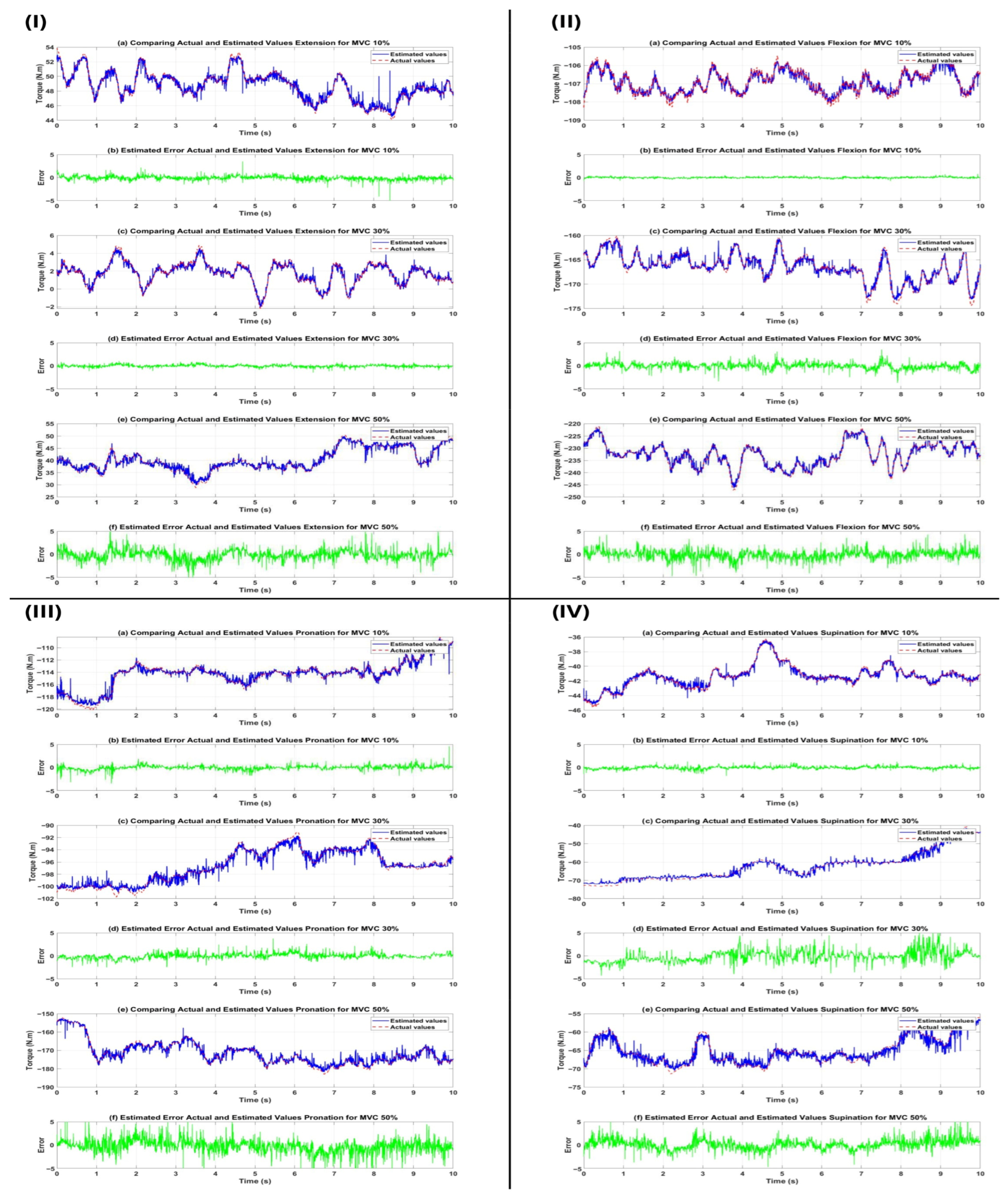

| Train | Validation | Test | All Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | 0.605 | 0.660 | 0.654 | 0.621 |

| RMSE | 0.610 | 0.665 | 0.659 | 0.626 |

| R2 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.961 | 0.965 |

| p-value | 0.012 | 0.130 | 0.193 | 0.030 |

| Corr | 0.986 | 0.982 | 0.983 | 0.985 |

| MVC | EST | RMSE | R2 | p-Value | Corr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | 10 | 0.034 | 0.030 | 0.955 | 0.000 | 0.982 |

| 30 | 0.664 | 0.657 | 0.963 | 0.038 | 0.985 | |

| 50 | 0.669 | 0.662 | 0.976 | 0.000 | 0.990 | |

| Extension | 10 | 0.495 | 0.491 | 0.968 | 0.000 | 0.987 |

| 30 | 0.960 | 0.961 | 0.968 | 0.214 | 0.988 | |

| 50 | 0.125 | 0.186 | 0.957 | 0.000 | 0.980 | |

| Supination | 10 | 0.982 | 0.983 | 0.974 | 0.000 | 0.988 |

| 30 | 1.111 | 1.116 | 0.981 | 0.000 | 0.991 | |

| 50 | 0.965 | 0.980 | 0.934 | 0.000 | 0.972 | |

| Pronation | 10 | 0.395 | 0.395 | 0.970 | 0.088 | 0.987 |

| 30 | 0.479 | 0.479 | 0.969 | 0.000 | 0.986 | |

| 50 | 1.255 | 1.274 | 0.963 | 0.000 | 0.983 |

| MVC | EST | RMSE | R2 | p-Value | Corr | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID Controller | Flexion | 10 | 0.840 | 0.969 | −46.716 | 0.000 | 0.576 |

| 30 | 3.306 | 3.494 | −7.845 | 0.000 | −0.180 | ||

| 50 | 4.535 | 4.724 | −11.118 | 0.000 | 0.084 | ||

| Extension | 10 | 2.308 | 2.341 | −8.890 | 0.000 | 0.651 | |

| 30 | 1.271 | 1.295 | −5.744 | 0.000 | 0.802 | ||

| 50 | 5.284 | 5.900 | −16.779 | 0.000 | 0.287 | ||

| Supination | 10 | 2.942 | 3.525 | −7.732 | 0.000 | 0.168 | |

| 30 | 11.653 | 17.240 | −99.980 | 0.000 | 0.247 | ||

| 50 | 10.329 | 11.145 | −55.293 | 0.000 | −0.132 | ||

| Pronation | 10 | 4.419 | 4.834 | −15.855 | 0.000 | 0.110 | |

| 30 | 5.292 | 5.479 | −13.903 | 0.000 | 0.443 | ||

| 50 | 14.448 | 14.608 | −85.272 | 0.000 | 0.041 | ||

| Impedance Controller | Flexion | 10 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.844 | 0.000 | 0.959 |

| 30 | 0.219 | 0.219 | 0.965 | 0.041 | 0.985 | ||

| 50 | 0.293 | 0.294 | 0.953 | 0.000 | 0.976 | ||

| Extension | 10 | 0.145 | 0.146 | 0.961 | 0.000 | 0.987 | |

| 30 | 0.085 | 0.085 | 0.971 | 0.230 | 0.993 | ||

| 50 | 0.341 | 0.345 | 0.939 | 0.000 | 0.974 | ||

| Supination | 10 | 0.204 | 0.205 | 0.971 | 0.000 | 0.985 | |

| 30 | 0.804 | 0.808 | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.860 | ||

| 50 | 0.664 | 0.673 | 0.794 | 0.000 | 0.898 | ||

| Pronation | 10 | 0.298 | 0.298 | 0.936 | 0.100 | 0.968 | |

| 30 | 0.338 | 0.338 | 0.943 | 0.000 | 0.974 | ||

| 50 | 0.837 | 0.849 | 0.617 | 0.000 | 0.840 | ||

| Sliding Mode Controller | Flexion | 10 | 0.126 | 0.129 | 0.158 | 0.000 | 0.602 |

| 30 | 0.212 | 0.212 | 0.968 | 0.002 | 0.990 | ||

| 50 | 0.222 | 0.222 | 0.973 | 0.000 | 0.989 | ||

| Extension | 10 | 0.193 | 0.196 | 0.931 | 0.000 | 0.966 | |

| 30 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.897 | 0.000 | 0.953 | ||

| 50 | 0.223 | 0.225 | 0.974 | 0.000 | 0.987 | ||

| Supination | 10 | 0.210 | 0.211 | 0.969 | 0.000 | 0.987 | |

| 30 | 0.236 | 0.240 | 0.963 | 0.000 | 0.982 | ||

| 50 | 0.235 | 0.238 | 0.974 | 0.000 | 0.990 | ||

| Pronation | 10 | 0.219 | 0.219 | 0.965 | 0.001 | 0.984 | |

| 30 | 0.224 | 0.224 | 0.975 | 0.020 | 0.988 | ||

| 50 | 0.235 | 0.238 | 0.970 | 0.000 | 0.986 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shakeriaski, F.; Mohammadian, M. Evaluation of Different Controllers for Sensing-Based Movement Intention Estimation and Safe Tracking in a Simulated LSTM Network-Based Elbow Exoskeleton Robot. Sensors 2026, 26, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020387

Shakeriaski F, Mohammadian M. Evaluation of Different Controllers for Sensing-Based Movement Intention Estimation and Safe Tracking in a Simulated LSTM Network-Based Elbow Exoskeleton Robot. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020387

Chicago/Turabian StyleShakeriaski, Farshad, and Masoud Mohammadian. 2026. "Evaluation of Different Controllers for Sensing-Based Movement Intention Estimation and Safe Tracking in a Simulated LSTM Network-Based Elbow Exoskeleton Robot" Sensors 26, no. 2: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020387

APA StyleShakeriaski, F., & Mohammadian, M. (2026). Evaluation of Different Controllers for Sensing-Based Movement Intention Estimation and Safe Tracking in a Simulated LSTM Network-Based Elbow Exoskeleton Robot. Sensors, 26(2), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020387