Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Scour Volume Detection of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Based on Side-Scan Sonar

Abstract

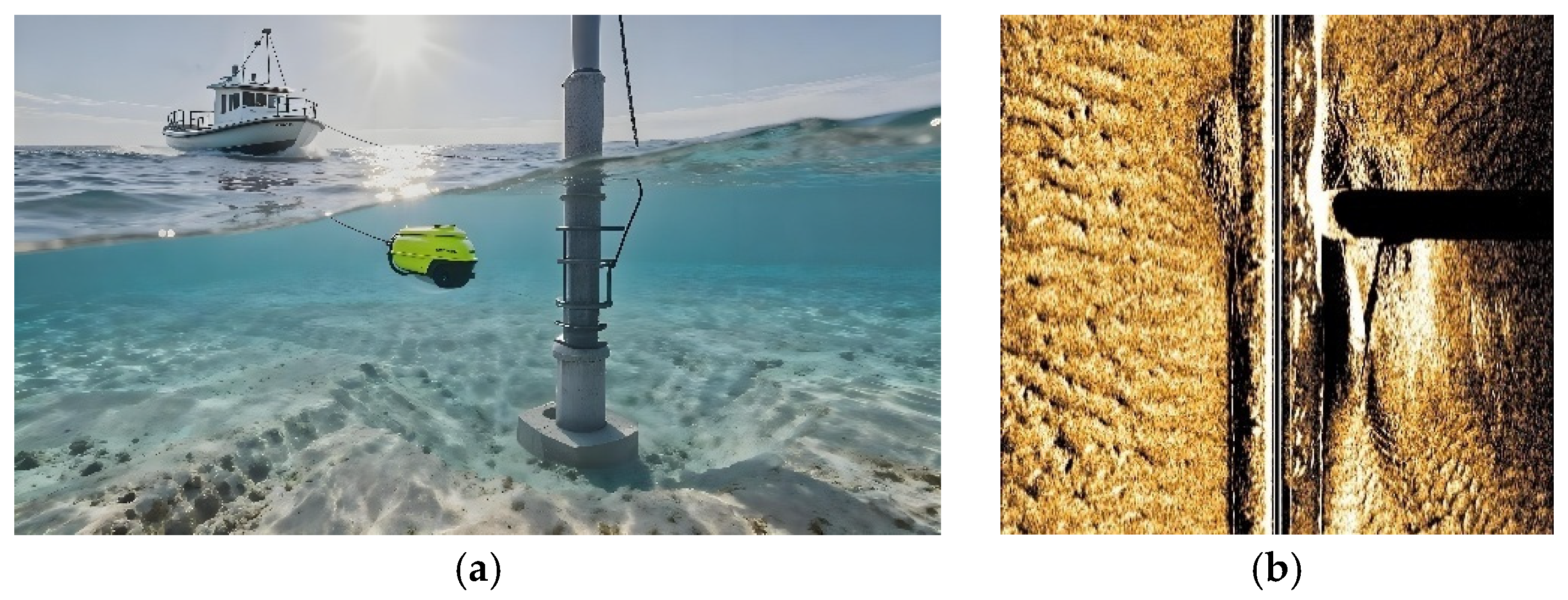

1. Introduction

2. Scour Pit Identification and Extraction from Side-Scan Sonar Images of Pile Foundations

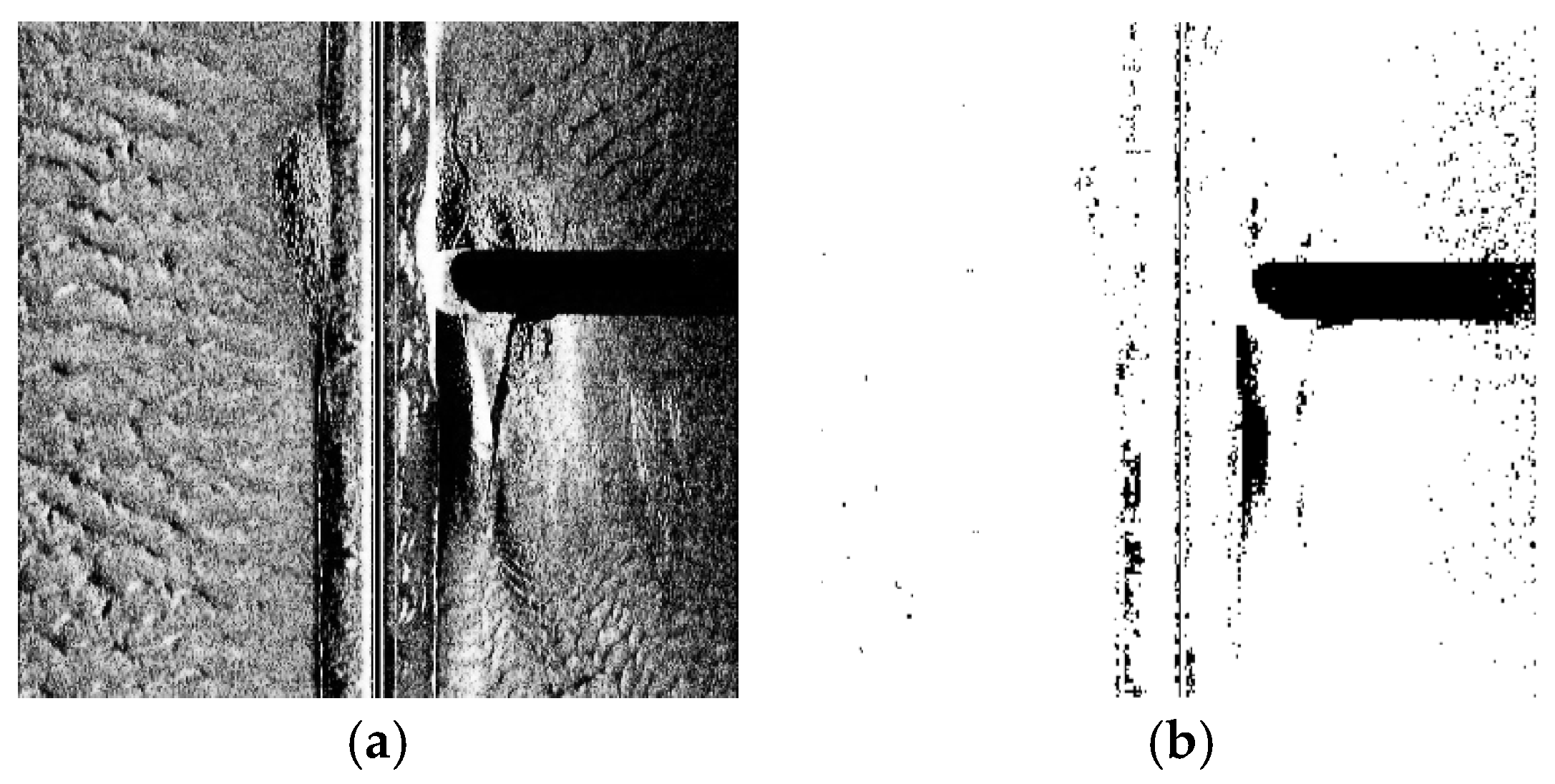

2.1. Binarization of Side-Scan Sonar Images of Pile Foundations

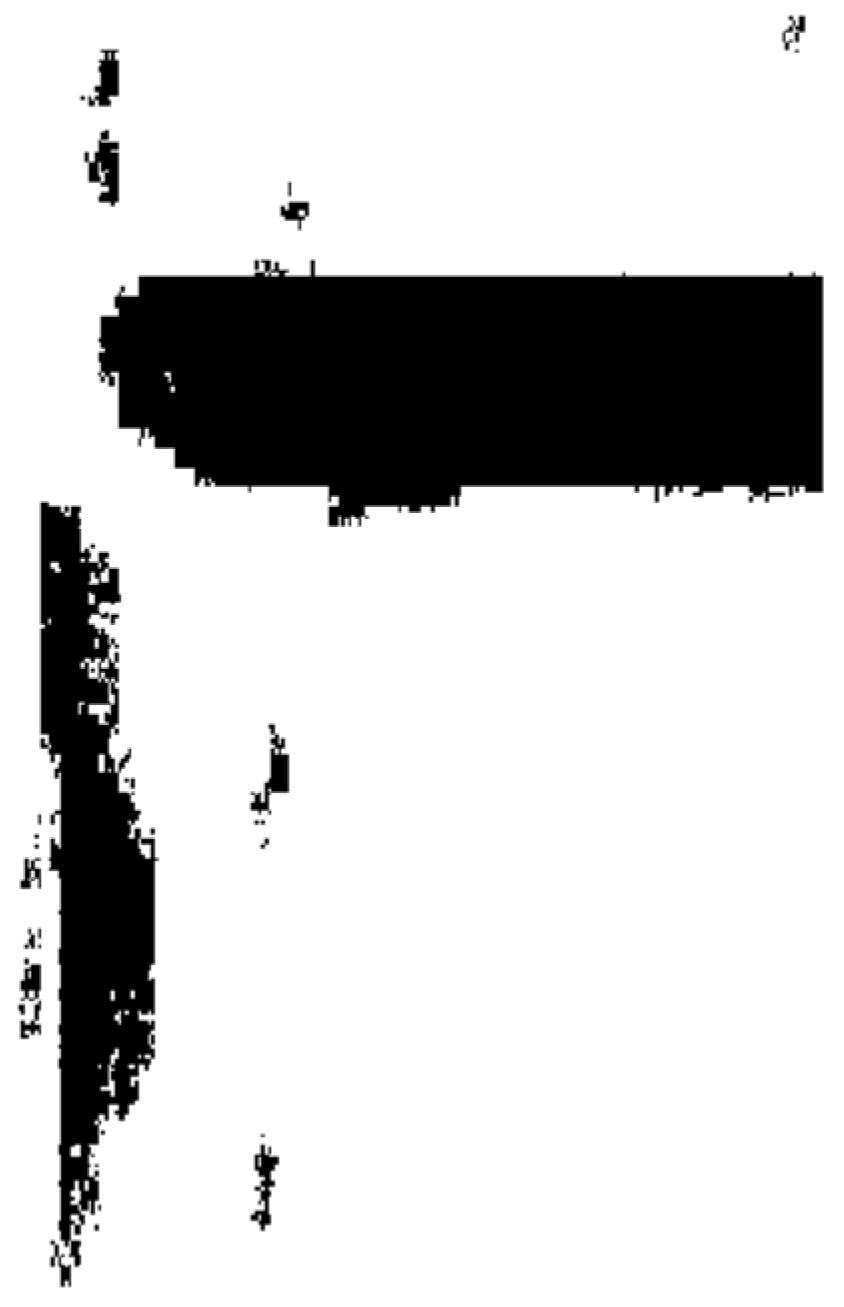

2.2. Scour Pit Extraction Based on Connected Components and Regional Features

2.3. Region Expansion and Merging of the Finally Preserved Connected Domains

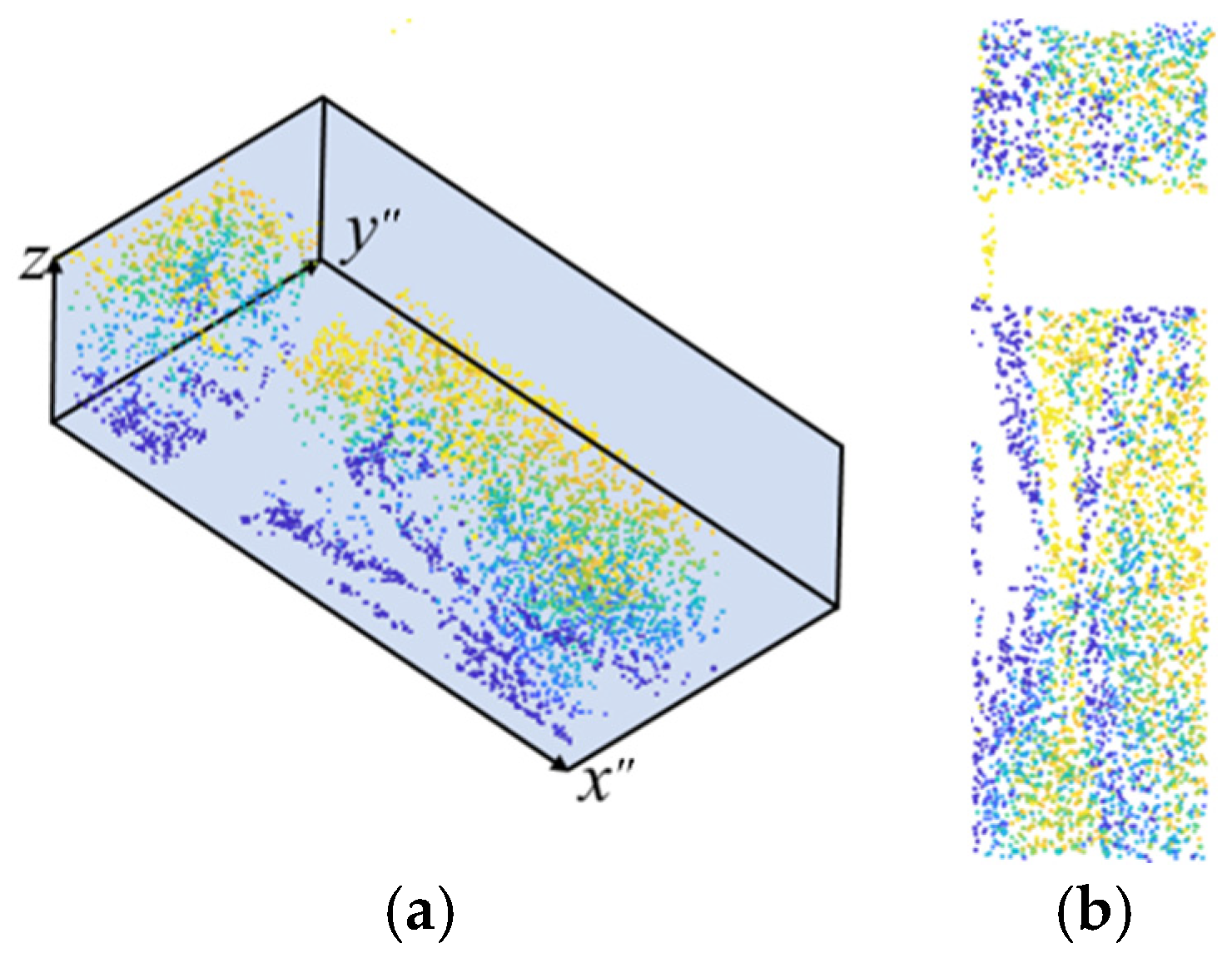

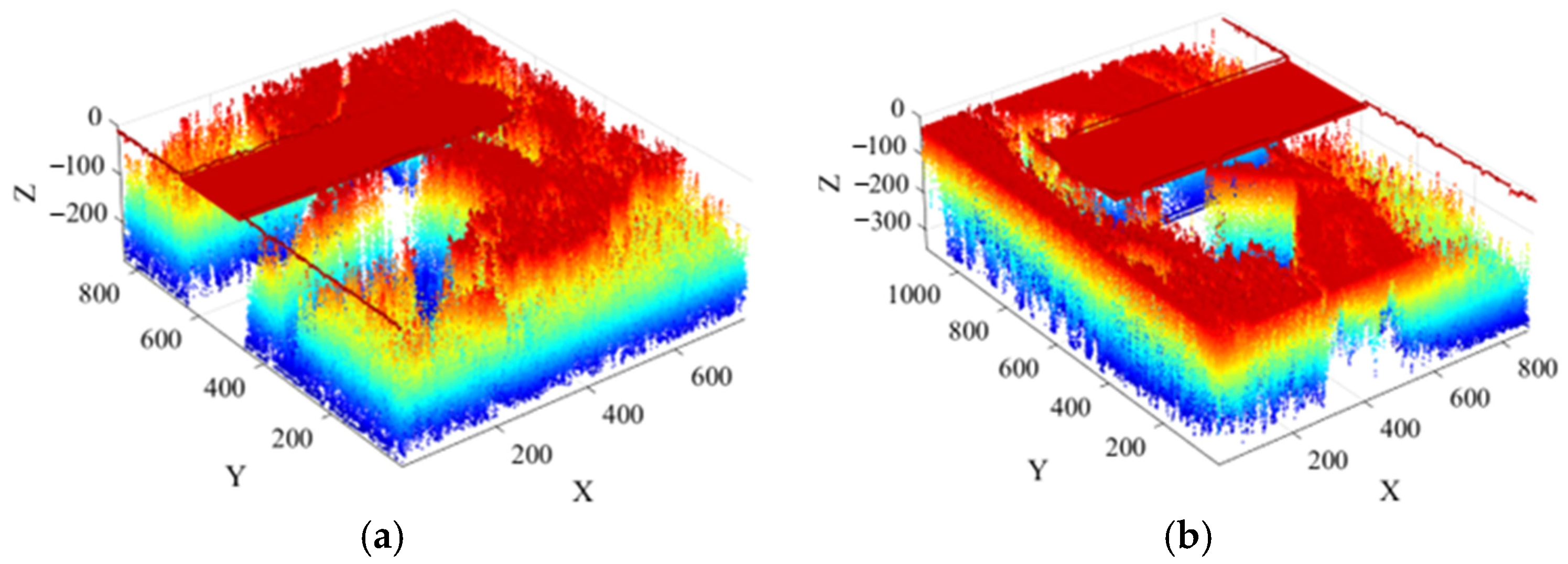

3. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Effective Grayscale Image of Pile-Foundation Scour Pits

3.1. Acquisition of Initial Depth Values for the z-Coordinate

3.2. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Effective Grayscale Image of Pile-Foundation Scour Pits Based on the SFS Method

4. Scour-Pit Point Cloud Filtering and Morphological Restoration

4.1. Point Cloud Filtering and Extraction

4.2. Clustering and Morphology Restoration of Scour-Pit Point Clouds

5. Volume Calculation of Scour Pits Around Offshore Wind Turbine Pile Foundations

6. Numerical Testing of Simulated Scour Environments

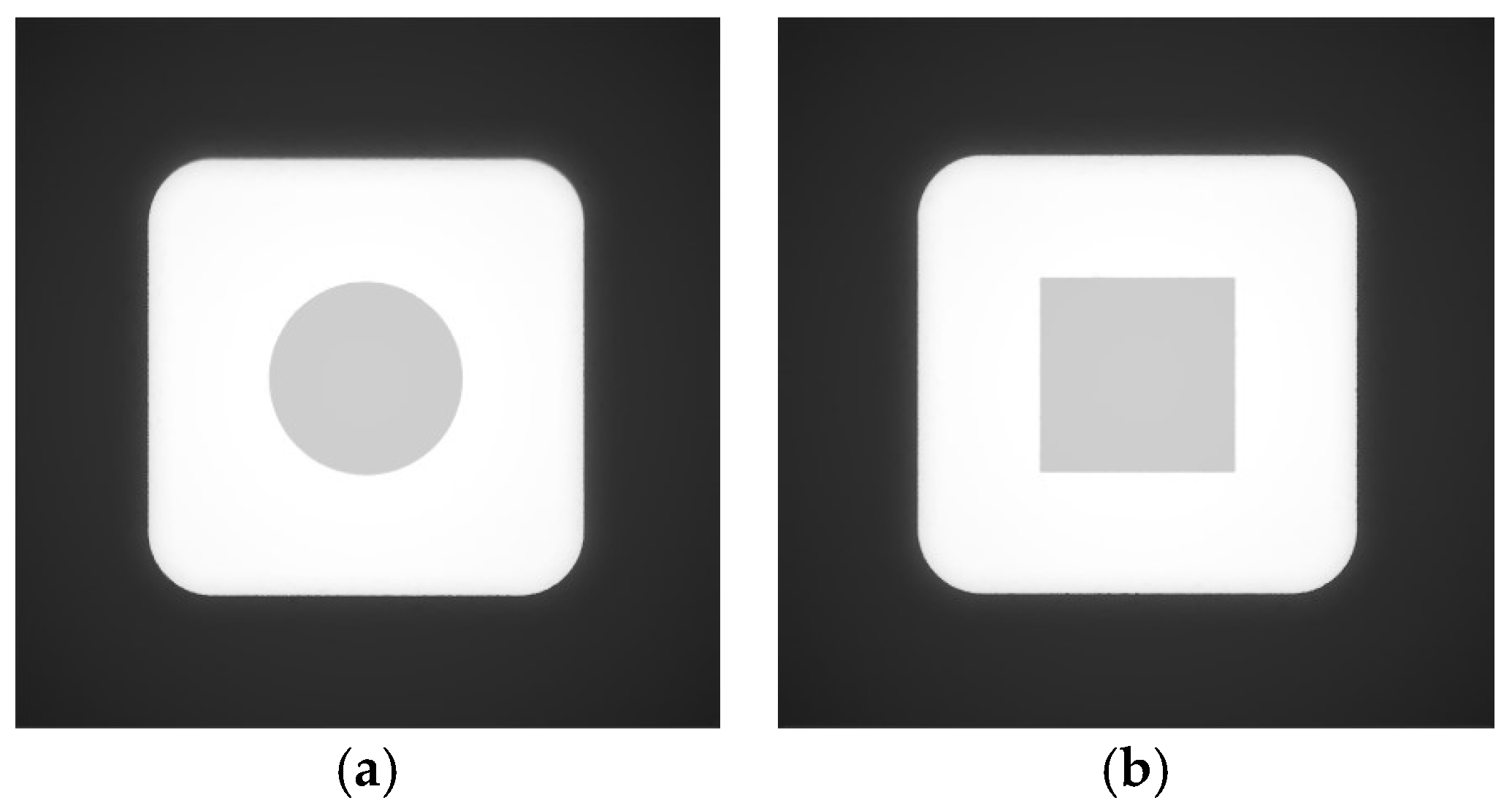

6.1. Test of Single Scour Pit Simulation Environment

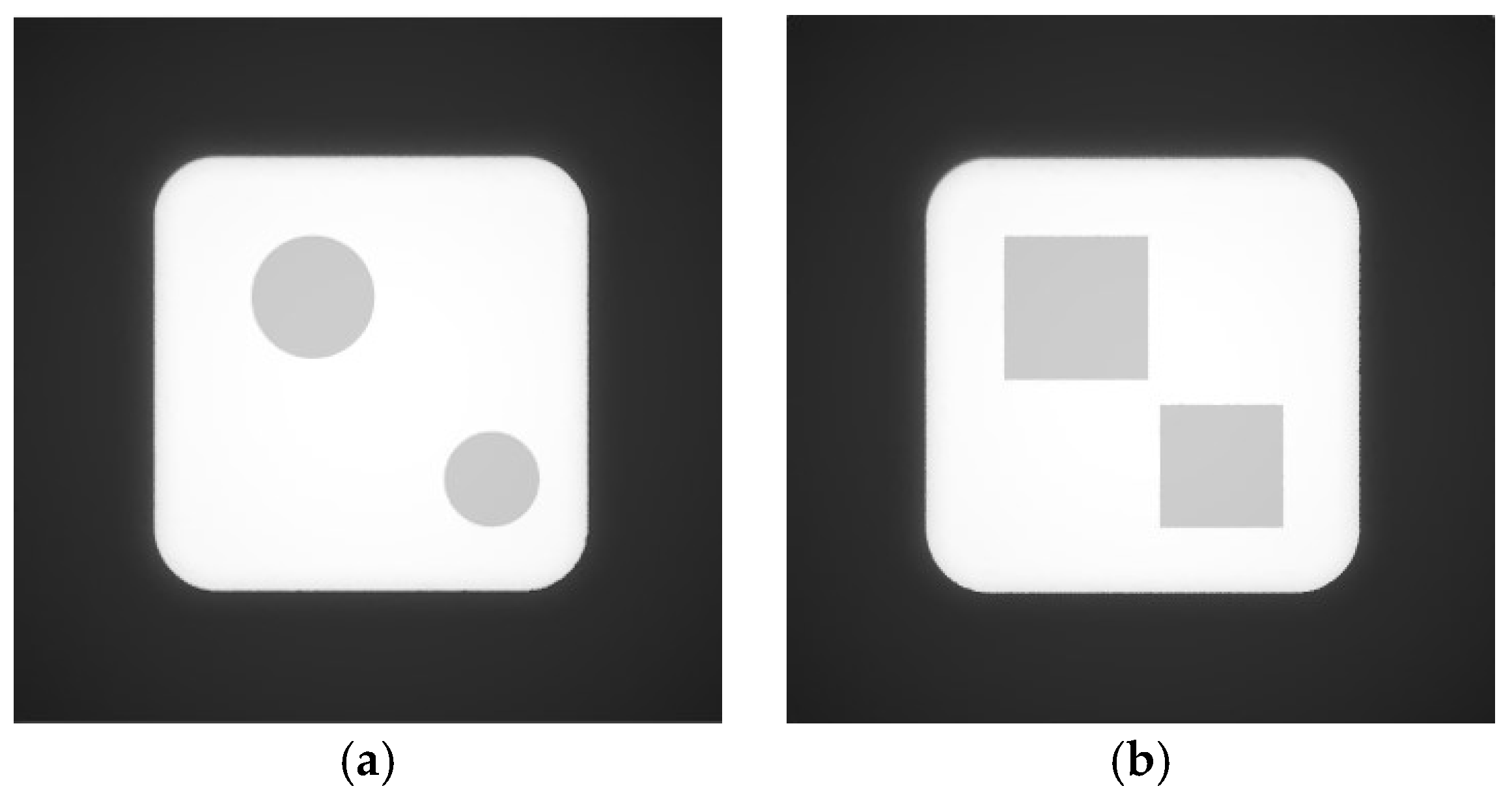

6.2. Test of Double Scour-Pit Simulation Environment

6.3. Test of Triple Scour Pit Simulation Environment

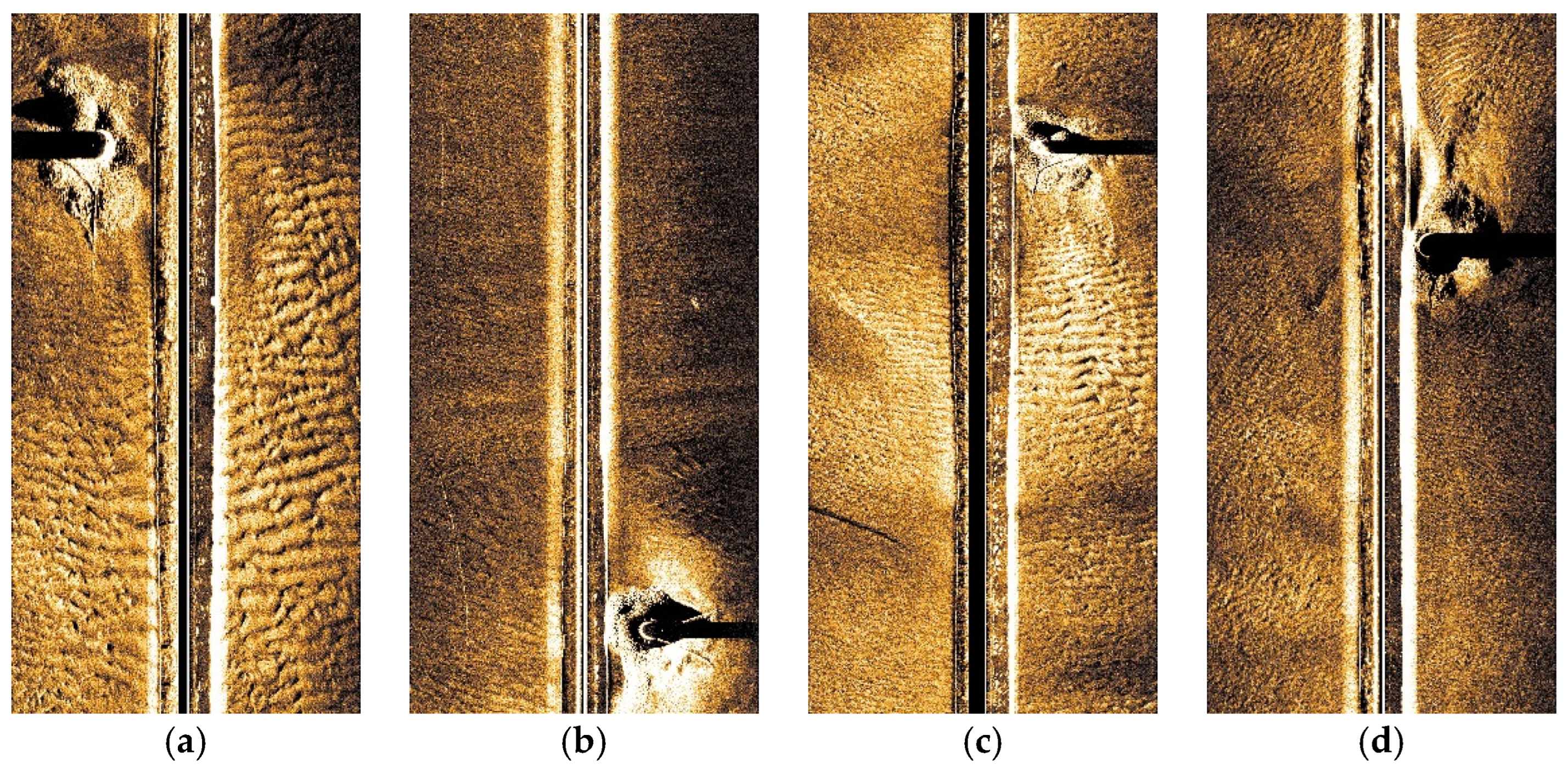

7. Experimental Testing in Real Scour Environments

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.Y.; Wan, X.; Lyu, J.Y.; Wu, B. Ship Path Planning in Offshore Wind Farm Waters Based on Improved A Algorithm*. Navig. China 2025, 48, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, T.; Yi, C.; Gao, W.; Li, S.Z.; Lyu, B.C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Bai, Z.L.T.; Wang, J.R.; et al. Development of Deep-Sea Floating Wind Power Technology. Strateg. Study Chin. Acad. Eng. 2025, 27, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.R.; Zhang, S.Y. Short Term Wind Speed Prediction by Fusing Swarm Decomposition and Transformer-KAN. J. Nanjing Univ. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.J.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, X.W. Detection of Apparent Defects of Underwater Structures in Turbid Waters Based on Polarization Imaging and Deep Learning. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.Y.; Li, J.; Dong, Z.P.; Hu, J.; Tang, Q.H. Denoising Processing and Analysis of ICESat-2 Seabed Photon Point Cloud Based on Improved Median Filtering Algorithm. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2024, 43, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Li, J.S.; Rao, Z.; Huo, Z.F. A Review of Terrain Elevation Matching Algorithms for Undersea Vehicles. J. Unmann. Undersea Syst. 2025, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Making Good Use of Submarine Cable Detection Equipment and Technologies, Maritime Hydrographic Survey Guarantees the Construction of Offshore Wind Farms. China Marit. Saf. 2022, 6, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.B. Application Conception of Intelligent Inspection of Offshore Wind Power. J. Ocean. Technol. 2022, 41, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, M. Study of Local Scour Around Rectangular and Square Subsea Caissons Under Steady Current Condition. Coast. Eng. 2024, 190, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lam, W.H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Guo, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Tan, T.H.; Chuah, J.H.; et al. Empirical Model for Darrieus-Type Tidal Current Turbine Induced Seabed Scour. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Yang, Q.; Zang, W.K.; Liu, H.J.; Liu, X.L. Advanced Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation on Influence of MS2AF on Scour Protection Considering Seabed Response: A Coupled CFD-FEM Method. Ocean Eng. 2025, 324, 120625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.Z.; Pan, G.S.; Liu, S.B.; Hu, Q.H. The Application of Side-Scan Sonar to Investigation of Submarine Pipeline Route. Chin. J. Eng. Geophys. 2016, 13, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.P. Study on Monitoring Methods for Operation and Maintenance of Offshore Wind Farm. Surv. Map. Geol. Miner. Resour. 2023, 39, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.L.; Wang, L.M.; Jin, S.H.; Zhao, J.H.; Huang, C.; Yu, Y.C. AUV-Based Side-Scan Sonar Real-Time Method for Underwater-Target Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, D.; Pere, P.; Sarah, P.; Jorge, G.; Albert, P.; Claudio, L.L.; Marta, A.C.; Araceli, M.; Aaron, M. Long-Term Morphological and Sedimentological Changes Caused by Bottom Trawling on the Northern Catalan Continental Shelf (NW Mediterranean). Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B. Integrated Application of Multiple Marine Geophysical Approaches in Submarine Pipeline Detection: A Case of Zhoushan Continental Water Diversion Project. Coast. Eng. 2020, 39, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.M.; Long, X.H.; Guo, J.L.; Gong, Q.S.; Ma, Q.L.; Xie, F.C. Contamination Detection in the Cultivation of Leukocyte Based on Image Sparsity Evaluation. Intell. Comput. Appl. 2025, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.H.; Tu, H.; Xue, Z.Y.; Zhou, W.; Haq, Z.U.; Luo, Z.G.; Wang, Z.X. Research on Automatic Identification Method of Aging Cracks in Rubber Materials Based on Computer Image Processing Technology. Polym. Bull. 2025, 38, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.W.; Xue, J.N.; Li, M.; Yan, S.Y.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, S.; He, R.F. Unstructured Road Semantic Segmentation Method Based on 3D Point Cloud of Open Pit Mine. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wan, Z.F.; Chen, B.; Chen, H.P.; Xu, K.; Li, S.W. Research on Automatic Extraction Method of Water Area Occupation Patches Based on GF-1 Imagery and Water Indices. Water Conserv. Sci. Technol. Econ. 2025, 31, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.F.; Guo, H.J. Volume Research of 3D Model Based on Alpha Shape. Comput. Technol. Autom. 2023, 42, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R. Credibility of 3D Volume Computation Using GIS for Pit Excavation and Roadway Constructions. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 8, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.L.; Wang, T.Y.; Cheng, D.Y.; Su, W.S.; Yao, P.; Ma, X.L.; He, M.Z. Enhanced Point Cloud Slicing Method for Volume Calculation of Large Irregular Bodies: Validation in Open-Pit Mining. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Theoretical Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detected Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detection Error (m3) | Error Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cylindrical | 4.948 | 4.944 | 0.004 | 0.08 |

| Square | 6.3 | 6.262 | 0.038 | 0.6 |

| Name | Theoretical Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detected Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detection Error (m3) | Error Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Cylindrical | 2.199 | 2.327 | 0.128 | 5.8% |

| Small Cylindrical | 1.407 | 1.324 | 0.083 | 5.8% |

| Large Square | 3.703 | 3.586 | 0.117 | 3.2% |

| Small Square | 2.800 | 2.678 | 0.122 | 4.3% |

| Name | Theoretical Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detected Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detection Error (m3) | Error Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Hexagonal | 3.073 | 3.096 | 0.023 | 0.7% |

| Medium Hexagonal | 2.405 | 2.352 | 0.053 | 2.2% |

| Small Hexagonal | 1.641 | 1.57 | 0.071 | 4.3% |

| Algorithm | Detected Scour-Pit Volume (m3) | Detection Error (%) | Computational Efficiency (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Method | 6.262 | 0.6 | 0.043 |

| Method 1 | 3.07 | 52.2 | 7.009 |

| Method 2 | 5.05 | 19.8 | 0.026 |

| Name | Scour Pit 1 (m3) | Scour Pit 2 (m3) | Scour Pit 3 (m3) | Scour Pit 4 (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# Pile | 2.4 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.46 |

| 2# Pile | 5.89 | 0.12 | 1.95 | 0.66 |

| 3# Pile | 0.26 | 1.21 | 0.19 | 2.19 |

| 4# Pile | 3.73 | 4.16 | 4.17 | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Yuan, M.; Yang, J. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Scour Volume Detection of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Based on Side-Scan Sonar. Sensors 2026, 26, 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020386

Wang Y, Tao L, Yuan M, Yang J. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Scour Volume Detection of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Based on Side-Scan Sonar. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020386

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yilong, Lijia Tao, Mingxin Yuan, and Jingjing Yang. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Scour Volume Detection of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Based on Side-Scan Sonar" Sensors 26, no. 2: 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020386

APA StyleWang, Y., Tao, L., Yuan, M., & Yang, J. (2026). Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Scour Volume Detection of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Based on Side-Scan Sonar. Sensors, 26(2), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020386