1. Introduction

Ultra-high voltage (UHV) transmission lines are crucial infrastructure for national energy strategies and major engineering projects such as the “West-to-East Power Transmission” program [

1,

2,

3]. These lines often traverse high mountains, canyons, and deserts, creating harsh construction environments that increase the need for high-altitude heavy-load UAV operations [

4,

5]. HD-UAVs, with strong load-carrying capacity and flexible deployment advantages, have enormous potential in material delivery, conductor pulling, and high-precision inspection [

6,

7,

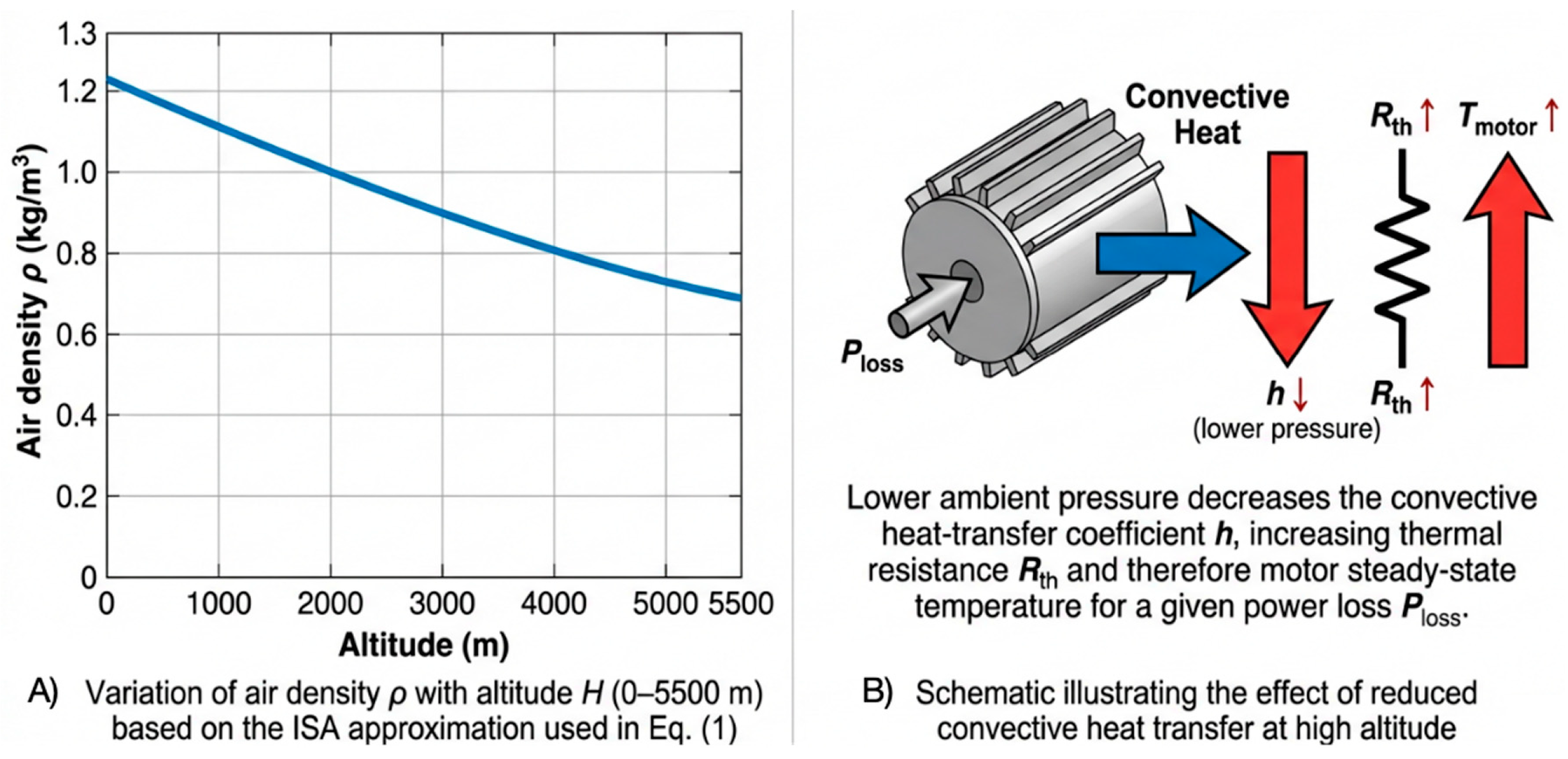

8]. They have become indispensable key technical equipment in UHV construction. However, severe challenges were posed to UAV power systems by rarefied air and low-temperature environments in high-altitude areas. With increased altitude, there was a sharp decrease in air density

and ambient temperature, directly influencing the’ lift force of the rotors and the’ heat dissipation performance of the motors: thrust attenuation limits the maximum load and safety margin, while deteriorated thermal management easily overheats motors and Electronic Speed Controllers (ESCs) [

9]. This may lead to system degradation or even shutdown risks, seriously endangering mission safety. Until now, existing methods have mainly addressed these issues by increasing redundant power or adopting conservative flight strategies, but they significantly reduce endurance and energy efficiency. Thus, developing an intelligent method that enables adaptive regulation and energy consumption optimization of power systems in complex plateau environments has become a key direction to enhance the unmanned construction capability of UHV projects.

The commonly used traditional regulation methods for the power system of UAVs mainly fall into three categories: first, attitude control based on PID [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], which can maintain the stability of flight but cannot dynamically respond to the influence of altitude variation on thrust characteristics; second, compensation methods [

16,

17] using the ISA model depend only on theoretical calculations without considering the interference from local outdoor temperature and humidity, which leads to insufficient accuracy and robustness; third, the Lookup Table approach [

18,

19] conducts power correction based on preset discrete compensation coefficients; yet, the interpolation accuracy and data dimensions will constrain it, which cannot work well for the nonlinear coupling of many influence factors such as altitude, temperature, and humidity. In recent years, with the rapid development of AI and computer technology, machine learning has been gradually applied in adaptive optimization for UAVs [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, existing studies generally focus on single-parameter regulation, lacking overall modeling and joint optimization for environmental factors, ETE, and thermal management constraints, which makes it hard to meet the complex requirements of HD-UAV plateau missions.

To address the above issues, this paper proposes a High-Altitude Adaptive Intelligent Regulation Network (HAARN) for HD-UAV power systems based on Deep Neural Networks (DNN). The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

1. Multi-sensor fusion-based high-precision environmental perception: Data fusion of barometric altimeters and GPS locators is realized, providing stable and high-precision real-time multi-dimensional environmental feature inputs (such as altitude, ambient temperature, air pressure) for HAARN.

2. End-to-end deep learning regulation architecture: A multi-layer HAARN model is built which can learn intelligently the complex nonlinear mapping relationship between the environmental parameters and optimal control commands (rotational speed, propeller pitch angle, current limit).

3. Synergistic optimization of energy consumption and reliability: With maximum thrust per unit of energy consumption (ETE) as the primary optimization objective and the output of current limits at the same time, this achieves the synergy in thrust compensation and thermal protection to improve reliability and endurance for plateau operations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 analyzes the quantitative impact of high-altitude environments on UAV power systems and discusses limitations of traditional regulation methods.

Section 3 presents the proposed HAARN framework, including multi-sensor fusion, dataset construction, network architecture, and optimization objectives.

Section 4 details the experimental setup and data-collection procedures, and

Section 5 presents experimental results and analysis, including static and dynamic performance comparisons, energy-efficiency evaluation, and thermal reliability tests. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

3. Intelligent Regulation Method of Power System Based on Deep Neural Network

3.1. Multi-Sensor Data Fusion Algorithm

To provide high-precision and high-reliability real-time altitude information, we adopts the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) algorithm to fuse data from the barometric altimeter () and GPS locator ().

The barometric altimeter provides high-bandwidth and low-drift relative altitude information but is susceptible to meteorological changes. GPS offers accurate absolute altitude information but has a low update frequency and occasional jumps. EKF leverages the complementarity of the two to achieve optimal state estimation.

The state variable

is defined as:

where

is the estimated altitude at time

k,

is the vertical velocity, and

is the vertical acceleration.

The state prediction model

adopts a uniform acceleration model for prediction:

where the state transition matrix

is modified to include the acceleration term:

is the sampling time interval, is the noise of the process, and its covariance is adjusted according to the kinematic characteristics of the UAV in the plateau. The diagonal elements of reflect the model’s confidence in the uncertainty of , which are usually increased under high wind speed conditions in the plateau.

The observation variable

is defined as:

The observation model is

, and the observation matrix

is:

is the observation noise and its covariance matrix . In practical applications, we dynamically adjust based on GPS signal quality (HDOP value) to reduce its weight when the GPS signal is poor, achieving robust fusion. The final output is a stable fused altitude estimate with a resolution better than 0.5 m.

3.2. Data Collection and Feature Engineering

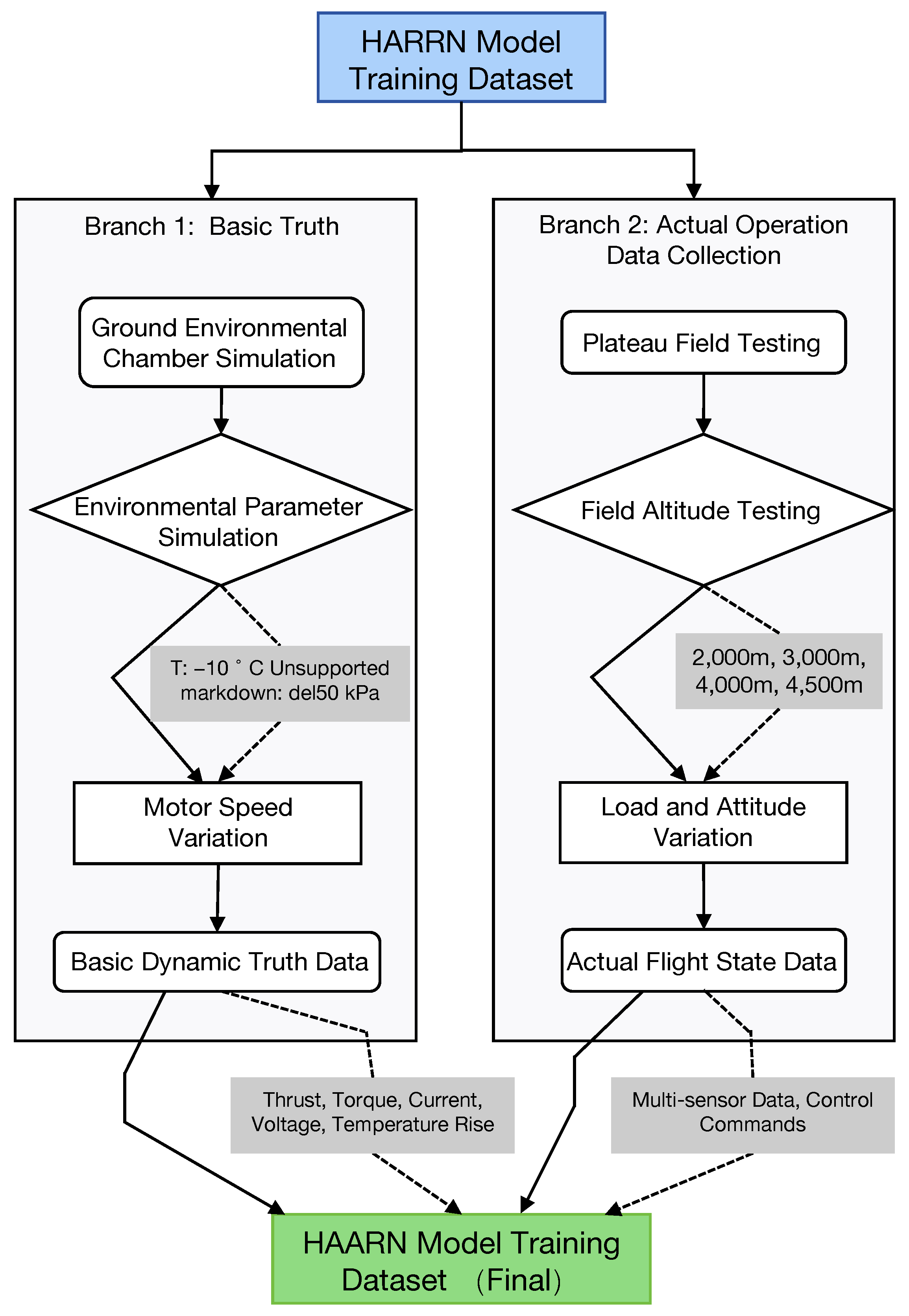

The training dataset of the HAARN model is the foundation for achieving accurate regulation. As illustrated in

Figure 2, data collection follows strict experimental protocols, covering all key operating quadrants in plateau environments. The establishment of data sources and collection environments combines two methods: first, in a ground environmental chamber, we simulated a temperature range of

to

and an air pressure range of 100 kPa to 50 kPa (corresponding to altitudes from 0 m to 5500 m). Real-time thrust, torque, current, voltage, and temperature rise data of the motor at different rotational speeds were accurately measured in the chamber to construct a basic dynamic truth database. Second, we conducted plateau field tests with varying loads (20 kg to 50 kg) and attitude changes (

tilt) at altitudes of 2000 m, 3000 m, 4000 m, and 4500 m, collecting multi-sensor data and control commands under actual flight conditions.

The generation of true value labels follows the criterion of maximizing the thrust per unit of energy consumption (ETE) while considering the safe temperature limit of the motor. The true values of and in are obtained, for each environmental state (a subset of ), through an exhaustive search and an inverse solution of the dynamic model to find the combination of and that can provide the required thrust and maximize . Meanwhile, the label is the theoretical safe current upper limit calculated based on the maximum allowable temperature rise and the thermal balance model under that state.

In the feature preprocessing stage, all sensor data are aligned and synchronized using high-precision timestamps and downsampled to a uniform frequency of . Subsequently, all input features are assigned to the interval using the Min-Max normalization method. The denormalization of the output is completed before flight control execution to ensure the output commands are within the physical safety range. The input feature set of the HAARN model has 7 dimensions, including , , , , , , and the newly added (motor surface temperature), thus achieving a comprehensive perception of the environment, dynamic state, and thermal state.

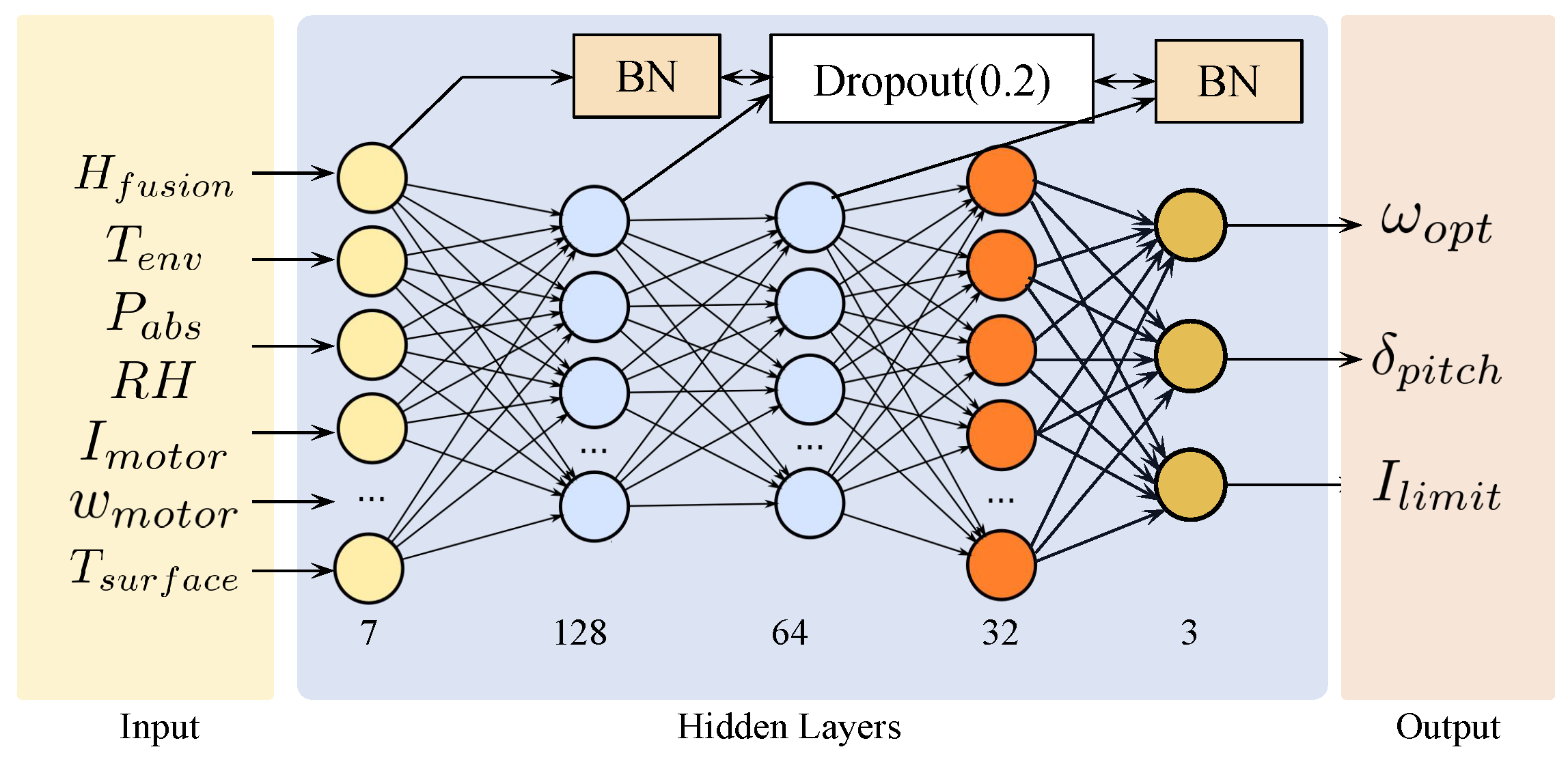

3.3. Construction of High-Altitude Adaptive Regulation Network (HAARN) Model

HAARN is a lightweight, four-layer fully connected network that minimizes model complexity while guaranteeing high-precision nonlinear mapping performance, with the requirement to meet the resource constraints and real-time demand for flight control computing units. The network topology is selected as (7-128-64-32-3). In that sense, it makes a good balance between accuracy and latency. Specifically, from the input layer (7 nodes) to the first hidden layer (128 nodes), mapping low-dimensional environmental features onto a high-dimensional feature space captures complex environmental coupling relationships, and then two subsequent hidden layers are used to extract, compress, and refine high-dimensional features for the mapping function learning to transform the environmental features into optimal control strategies. The detailed architecture of the network is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Specifically, BN is applied after Hidden Layer 1 and Hidden Layer 3 to stabilize the internal covariance shift of the network at first. This ensures stable training and fast convergence of the model under significantly different data distributions (Domain Shift) collected at high altitudes and sea levels. Second, a Dropout layer with in Hidden Layer 2 serves as a regularization method to reduce co-adaptation between neurons, enhancing generalization capability in unknown or transiently changing plateau meteorological conditions. Finally, for the selection of the activation function, ReLU is adopted for all hidden layers to guaranty computational efficiency. In the output layer, and employ linear activation functions to allow free adjustment within the target range; for , the Sigmoid activation function is adopted, followed by scaling and translation operations to strictly limit the current between the upper and lower limits of the safe operating current of the motor for physical constraints. It is worth noting that the generalization across different UAV platforms mainly requires adjusting the scaling ranges of motor–propeller parameters, while the core HAARN structure remains unchanged.

3.4. Optimization Objective and Loss Function Improvement

The training objective of HAARN is based on maximizing energy efficiency while taking thermal reliability as an insurmountable constraint. The final hybrid loss function adopted

achieves synergistic optimization of energy efficiency and reliability. Among them, the thrust energy efficiency loss term

uses the standard Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the main optimization term:

By minimizing this loss, the network’s predicted control commands are prompted to approach the maximum true ETE values at each environmental point to the greatest extent. Meanwhile, to actively manage thermal risks, a dynamic thermal limit and penalty term

are introduced. We established a first-order thermal model based on the equivalent heat capacity and thermal resistance of the motor windings to dynamically calculate the maximum safe current

during training. This model is based on the thermal balance equation:

. Based on this model and the

threshold, we dynamically calculate

and construct the penalty term:

where

is the current limit in the output

. The weight coefficient

is set to a high value to assign a higher priority to optimization to thermal limits, ensuring that thrust compensation does not come at the cost of motor life. It should be noted that the thermal model used in

is calibrated under controlled temperature–pressure conditions and is mainly designed as a conservative constraint; therefore, it does not explicitly target highly transient or extreme meteorological variations.

3.5. Flight Control Platform Deployment of Intelligent Regulation Strategy

Real-time deployment of the HAARN model is essential to ensure stable UAV operation in plateau environments. The model is deployed directly on the onboard flight-control computing unit (e.g., a high-frequency MCU integrated into the main control board), rather than on external edge-computing devices, to guarantee compactness, robustness, and deterministic real-time behavior.

To satisfy the hard real-time constraints of the flight-control loop, the trained HAARN model undergoes strict post-training optimization before deployment. All network weights and activations are quantized from 32-bit floating-point (FP32) to 8-bit fixed-point (INT8), reducing the model size by approximately 75% and yielding a 3–5× inference speedup compared with the FP32 implementation. The quantized model is compiled with architecture-specific optimizations targeting ARM Cortex-M7/H7 microcontrollers, enabling efficient execution without dedicated neural acceleration hardware. After optimization, the INT8-quantized HAARN model occupies approximately 28 kB of RAM for weights and intermediate buffers, and 48 kB of flash memory for the model binary. On a representative flight-control computing unit (ARM Cortex-M7@400 MHz), the average per-inference execution time, including feature normalization and output denormalization, is 8–10 ms. The target flight-control computing unit is based on an STM32H7-series microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland), featuring an ARM Cortex-M7 core running at 400 MHz.

The HAARN module is integrated into the main flight-control loop and executed at 20 Hz, corresponding to a 50 ms control-cycle budget. At the perception stage, the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) outputs the fused altitude-related state together with six additional environmental and flight-state features . These features are processed by the onboard computing unit, and HAARN completes inference within ≤10 ms to generate the regulation output . The observed end-to-end latency from EKF output to the updated Electronic Speed Controller (ESC) current limit does not exceed 12 ms. When operating at 20 Hz, HAARN inference accounts for approximately 4–8% of the available CPU cycles on the test MCU, leaving more than 90% computational headroom for other time-critical modules, including EKF, PID control, and sensor fusion. Stack and heap usage during inference remain well within the available memory budget of the flight-control board.

At the execution stage, the predicted thrust regulation commands and are applied as feedforward compensation signals and superimposed on the baseline PID controller output. In parallel, the predicted current limit is transmitted to the ESC as a dynamic upper bound. When the motor current approaches this limit, the ESC softly constrains power output, enabling proactive thermal protection without relying solely on delayed temperature sensor feedback. Importantly, HAARN operates as an auxiliary feedforward module rather than a replacement for the core stabilization loop. The PID controller remains the primary safety-critical component, and in the presence of abnormal predictions, timing overruns, or sensor inconsistencies, the system automatically disables HAARN and reverts to pure PID control, thereby preserving deterministic flight-control behavior and ensuring operational safety.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

In this section, we present the experimental results. Subsections include: static regulation performance comparisons (steady hover), dynamic thrust step-response analysis, energy-efficiency (ETE) comparisons across altitudes, and thermal-reliability assessments. Each experiment is reported with measurement details, uncertainty quantification, and comparison against baseline methods.

5.1. Static Comparison Experiment of Regulation Performance

To assess the steady-state performance of HAARN in suppressing plateau thrust attenuation, three fixed-height hovering tests were conducted in a typical plateau environment with altitude m and ambient temperature , maintaining constant thrust required by heavy-duty tasks. Three different regulation methods were compared: the traditional PID control based on sea-level parameters, a simple lookup table method modified by the ISA model, and the proposed HAARN method.

5.2. Dynamic Characteristic Analysis of Thrust Response

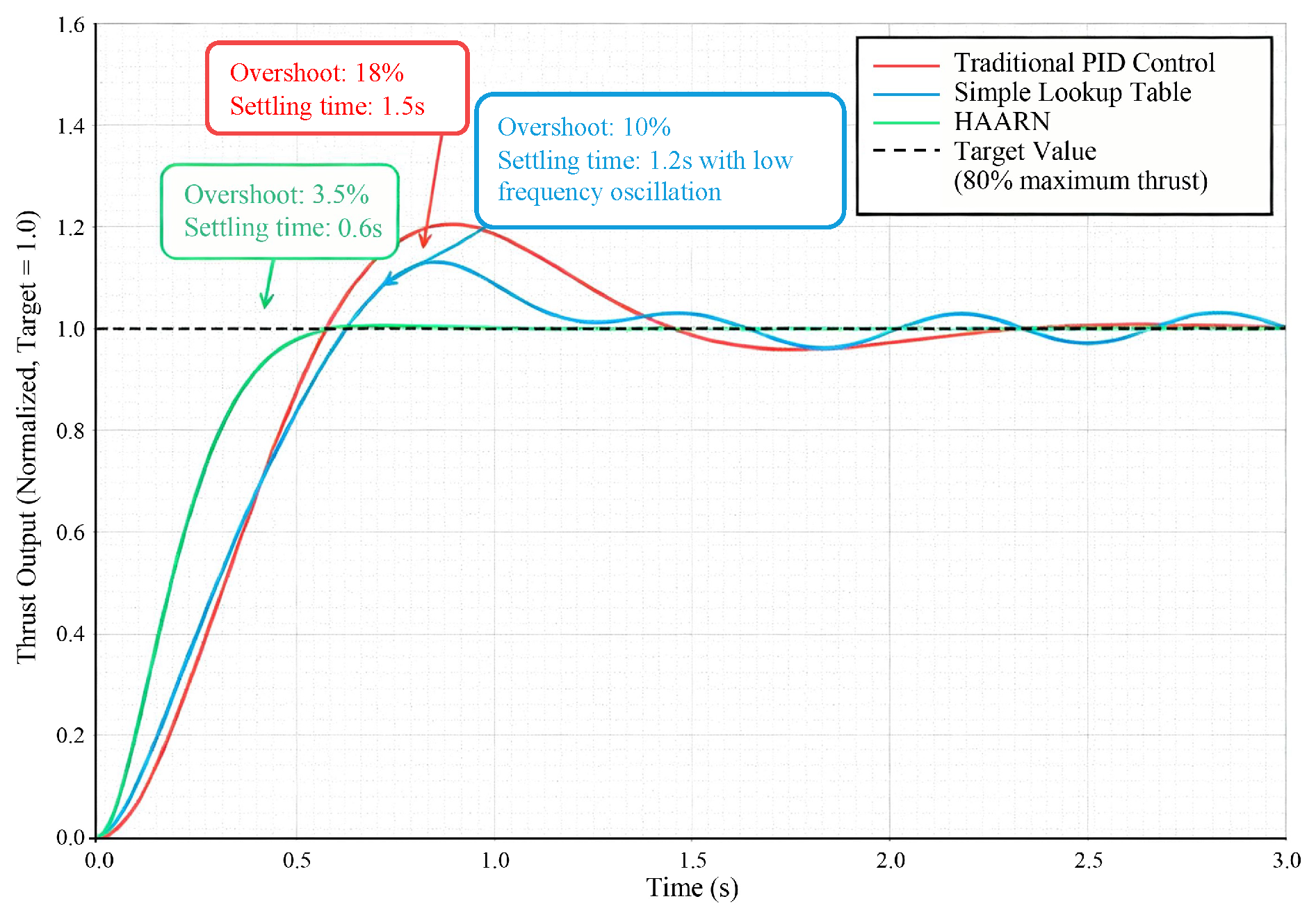

The thrust step response test was performed to assess the adaptability of the control system to sudden changes in the external environment and flight commands. In the experiment, at an altitude of 4000 m, the system inputted a step command from hovering thrust to 80% of maximum thrust. Then, the dynamic characteristics of the thrust output were analyzed. The important indicators of dynamic performance include Rise Time, settlement Time, and Overshoot.

5.2.1. Thrust Step Response Curve Comparison

Figure 4 clearly illustrates the comparative dynamic performance of the three methods. Due to its system gain variation due to high-altitude thrust characteristics, the conventional PID demonstrates 18% overshoot and a settling time of as long as 1.5 s, which will inevitably lead to a severe oscillation and instability of the attitude during actual flight. The simple lookup table method, although by compensation reduces the overshoot to 10%, still possesses a low-frequency oscillation of about 3% in the process of stabilization, due to the discreteness of its compensation coefficients. The HAARN method has an overshoot of only 3.5% and a significantly shortened settling time of 0.6 s. This excellent dynamic performance is directly attributed to the thrust feedforward compensation mechanism described in

Section 3.5: The optimal commands predicted in real-time

and

by HAARN are used directly as feedforward signals to correct the throttle command, reducing the dependence of the underlying PID controller on errors. This allows the system to predict in advance and adjust quickly, guaranteeing the attitude stability and safety of the heavy-duty UAV while going through complex airflow environments. The quantitative comparison of key dynamic performance indicators at 4000 m altitude is summarized in

Table 2.

5.2.2. Thrust Response to 80% Step Command at 4000 m

Figure 5a compares time-series of thrust, motor current, and speed for an 80% step thrust test at 4000 m using PID (blue), lookup table (orange), and HAARN (green). HAARN shows 3.5% overshoot (vs. 10% and 18%), 0.5 s settling time (vs. 1.0 s and 1.5 s), and lower steady-state currents (150–165 A vs. 180 A), improving efficiency in high-altitude conditions.

5.2.3. Normalized Thrust Step-Response Curves at 4000 m

Figure 5b overlays normalized thrust step-responses at 4000 m. PID: 18% overshoot, 0.6 s rise, 1.3 s settling. Lookup: 10% overshoot, 0.3 s rise, 1.0 s settling. HAARN: 3.5% overshoot, 0.3 s rise, 0.6 s settling. HAARN provides faster, more stable regulation in thin air.

5.2.4. Motor Temperature During Continuous Hovering at 4500 m

Figure 5c shows motor temperature over 30-min maximum-load hovering at 4500 m and 5 °C. PID exceeds thermal threshold, shutting down at 10 min. Lookup approaches unsafe levels. HAARN stabilizes at 80 °C, staying below threshold, enabling sustained operation without damage.

5.2.5. Schematic of the Test Setup

Figure 5d diagrams the test rig, including octocopter UAV with PT1000 sensors, environmental sensors (barometer, GPS, IMU), vacuum pump, six-axis load cell, tether, cold air circulation, and real-time data logging. This setup replicates high-altitude conditions for accurate performance measurements.

5.3. Adaptability and Energy Consumption Synergy Analysis

This section is devoted to the analysis of the synergistic optimization effect of HAARN in terms of energy efficiency ETE and thermal reliability.

5.3.1. Energy Efficiency Comparison Analysis

We compared ETEs of the three methods at different altitudes and demonstrated that a higher ETE indicates stronger endurance. In flight tests, ETE is computed by integrating instantaneous battery power and actual thrust T.

5.3.2. ETE Comparison at Different Altitudes

As indicated in

Figure 6, the HAARN approach has the highest ETE at all altitudes. At an altitude of 4000 m, HAARN is about 8.3% higher compared to the simple lookup table method and 15.2% higher compared to traditional PID. This confirms that HAARN can achieve an optimal balance between thrust compensation and energy consumption management using the loss function

during the training process, thus prolonging the endurance time of heavy-duty UAVs at high altitudes.

5.3.3. Dynamic Thermal Management and Reliability

Analysis We further tested the thermal management performance of the system under continuous hovering conditions at an extreme altitude of 4500 m with maximum load. The test lasted 30 min with the motor surface temperature reaching as the thermal safety threshold.

As shown in

Table 3, due to dynamic current limit

, HAARN maintains the peak motor temperature at

, far below the upper threshold

, without triggering any thermal protection in 30 min. By contrast, the conventional PID controller triggered a shutdown protection due to an excessive rise in temperature in 15.5 min, where the peak temperature increased to

. The lowest rate of temperature increase is

as HAARN effectively tunes an active thermal management strategy through the penalty term

. In addition to achieving the highest energy efficiency, HAARN has the longest continuous operating time under extreme conditions, significantly improving the operational reliability and safety of heavy-duty UAVs during plateau UHV tasks.

5.4. Model Quantization Evaluation

To evaluate the effect of the FP32-to-INT8 quantization on system performance, we compare the thrust compensation accuracy, thermal behavior, and control dynamics before and after quantization. As shown in

Table 4, the INT8 model preserves the performance of the FP32 model with negligible differences. The thrust loss rate, ETE, overshoot, and peak motor temperature remain almost unchanged, while the model size is reduced by more than 70% and the inference latency improves from 35 ms to 7 ms, ensuring real-time execution on embedded hardware.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we proposed HAARN, a lightweight deep neural network–based regulation method for the high-altitude adaptability of heavy-load UAV power systems. By fusing multi-sensor environmental and system-state inputs and optimizing for thrust-per-unit-energy (ETE) under thermal constraints, HAARN reduced thrust attenuation to 2.5% at 4000 m and achieved energy-efficiency improvements of 8.3–15.2% compared to baseline methods across tested altitudes. The model’s dynamic current-limiting strategy also improved thermal reliability, enabling continuous hovering at extreme altitudes without triggering thermal protection.

Future work will focus on extending HAARN to online adaptive learning (e.g., integration with DRL) to support rapidly changing environments, expanding evaluation to additional UAV platforms and longer endurance tests, and integrating transient meteorological factors such as wind gusts into the regulation framework. We will also release anonymized dataset summaries and inference-code benchmarks to aid reproducibility.