A 5000 Fps, 4 Megapixel, Radiation-Tolerant, Wafer-Scale CMOS Image Sensor for the Direct Detection of Electrons and Photons †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Design

2.1. Stitching Plan and Architecture Decisions

2.2. Pixel

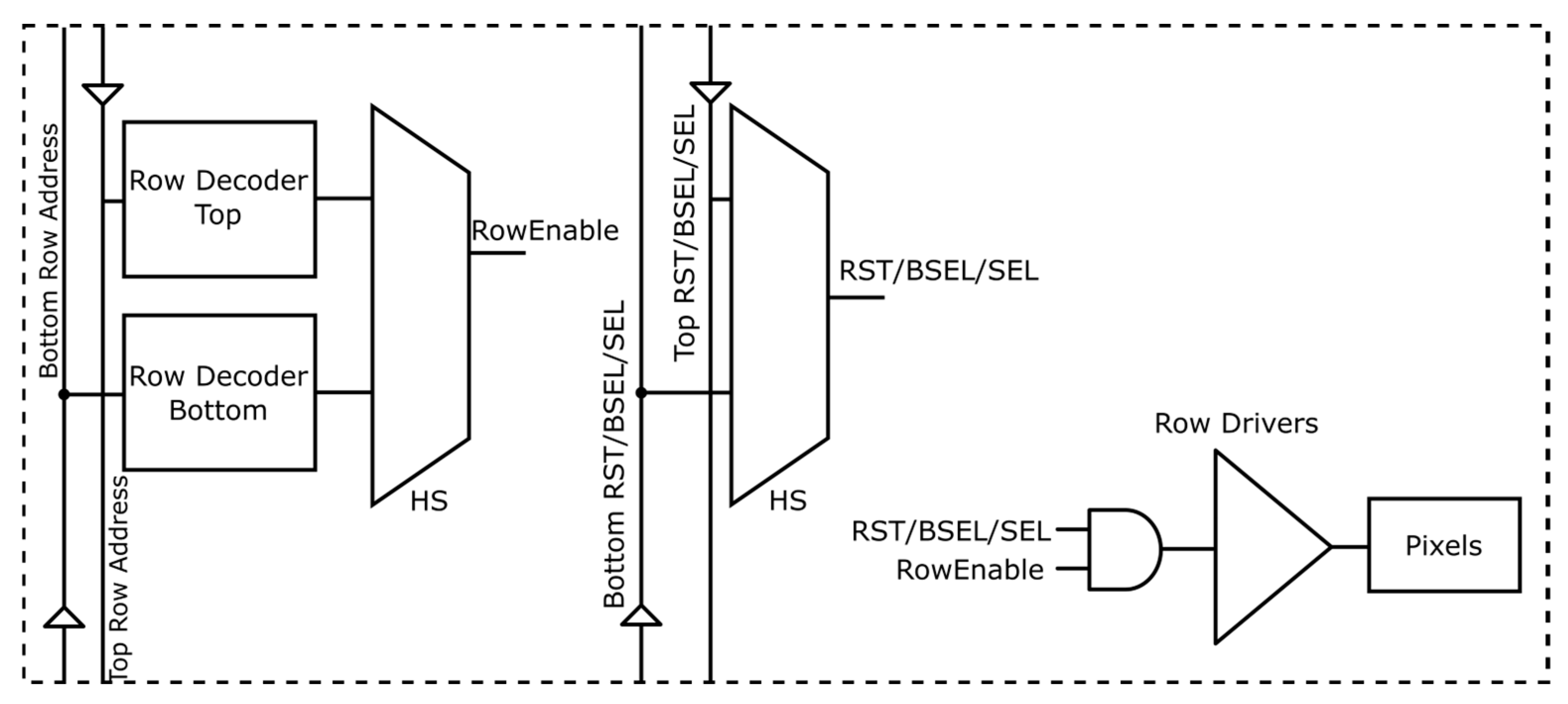

2.3. Analogue Readout

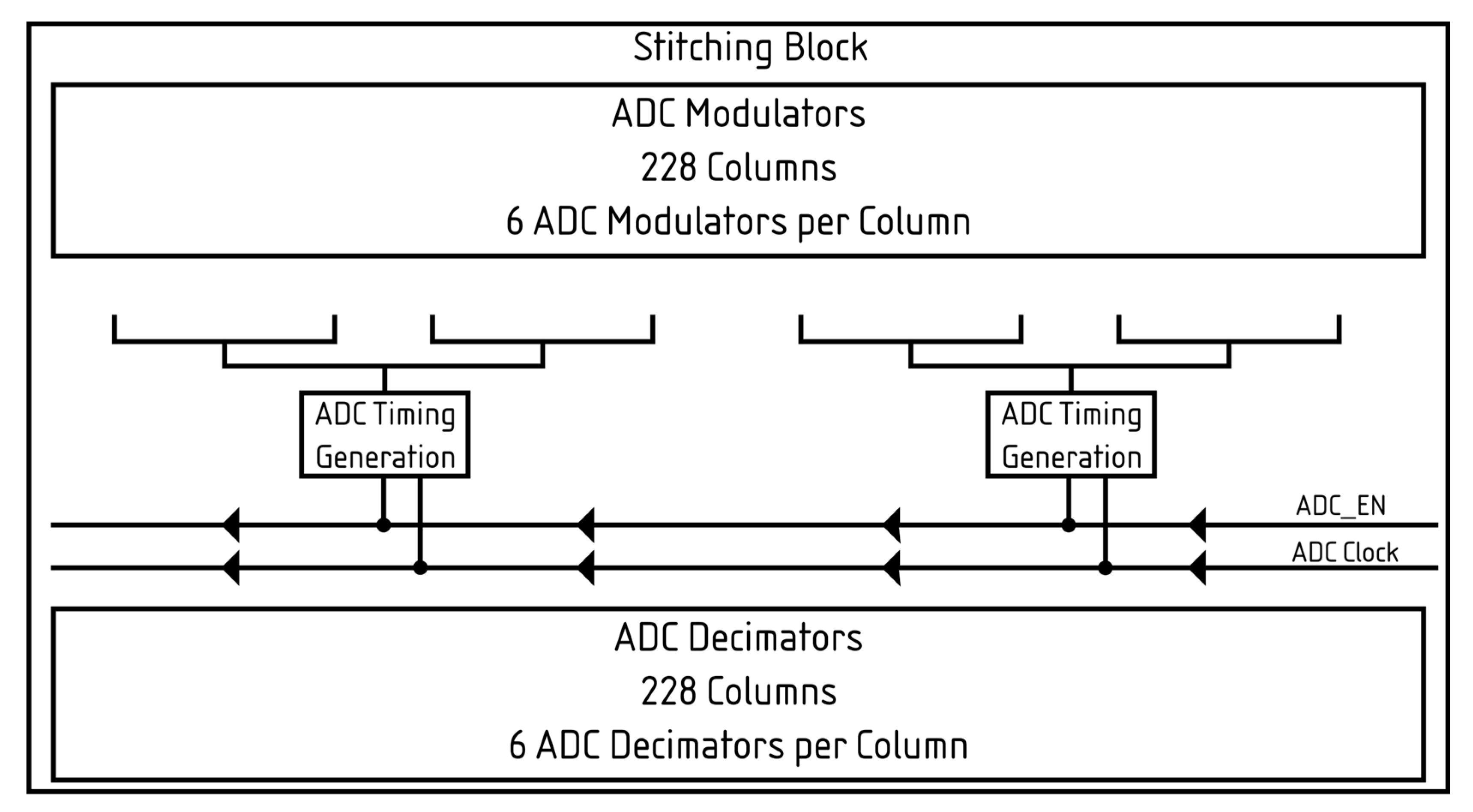

2.4. Digital Readout

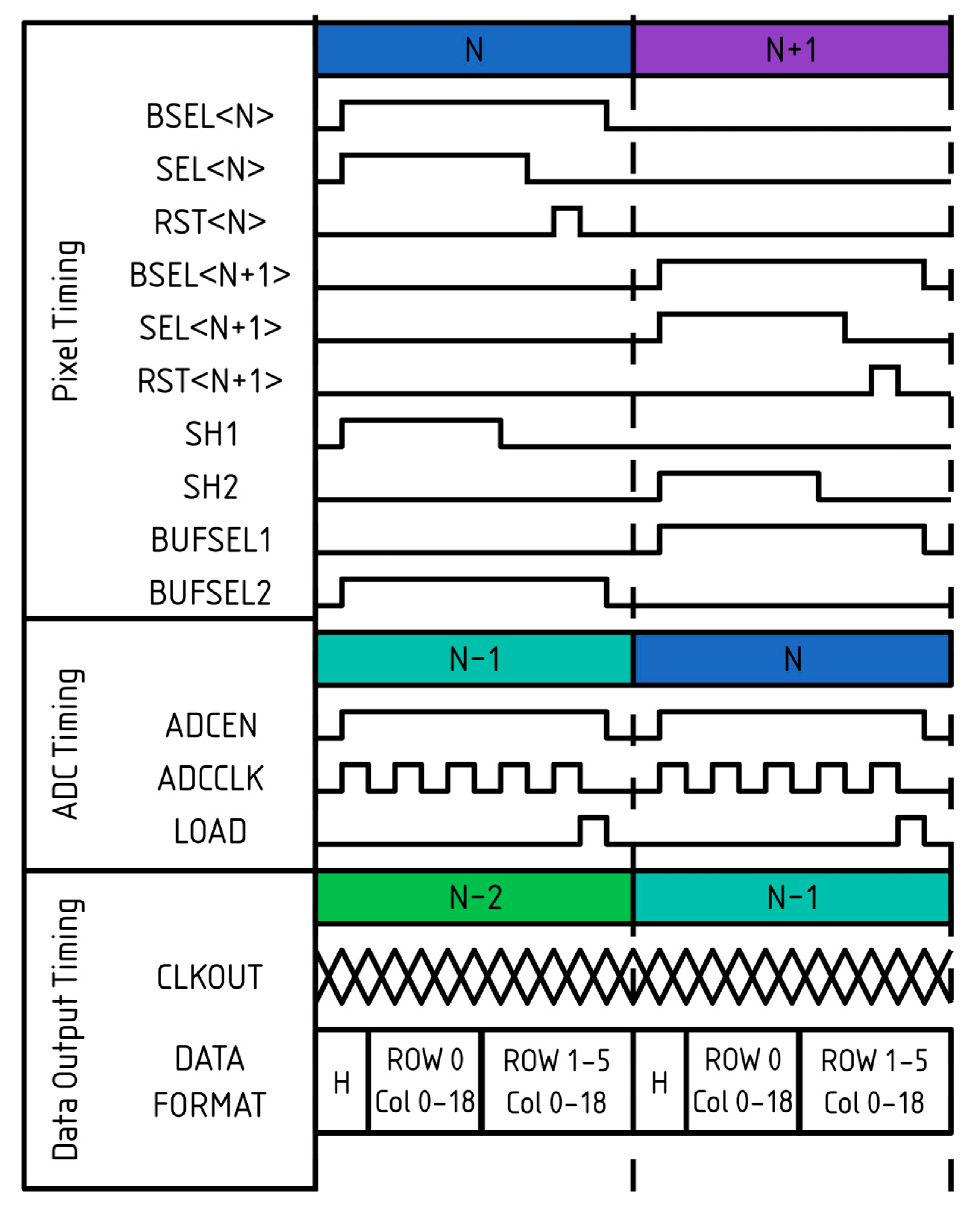

2.5. Readout Timing

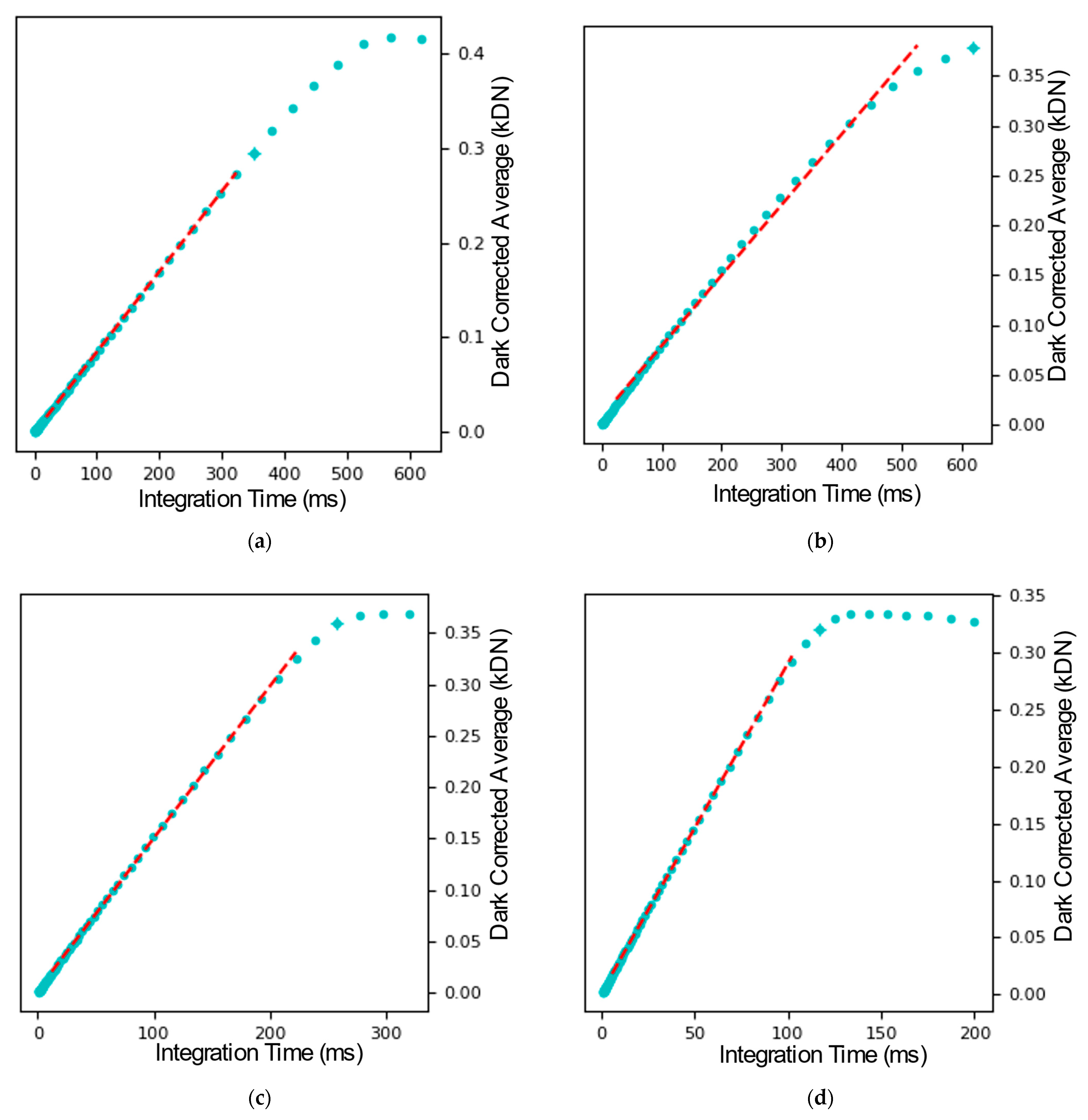

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGA | Programmable Gain Amplifier |

| ADC | Analogue to Digital Converter |

| DDR | Double Data Rate |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| CMOS | Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor |

| CIS | CMOS Image Sensor |

| COB | Chip-On-Board |

| FPN | Fixed-Pattern Noise |

| SPI | Serial-Parallel Interface |

| PPPD | Partially Pinned Photodiode |

| HS | Half Select |

| LVDS | Low-Voltage Differential Signalling |

| CryoEM | Cryogenic Electron Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| S/H | Sample and Hold |

| FSI | Front Side Illuminated |

References

- Farrier, M.G.; Achterkirchen, T.G.; Weckler, G.P.; Bosiers, J. CMOS Active Pixel Detectors for Radiography. In Proceedings of the 2009 Image Sensor Workshop, Bergen, Norway, 25–28 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf, L.; Tomer, L.; Raz, R.; Amos, F. Enhanced X-RAY CMOS Sensor Panel for Radio and Fluoro Application Using a Low Noise Charge Amplifier Pixel with a Partially Pinned PD. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Image Sensor Workshop, Hokkaido, Japan, 8–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Korthout, L.; Verbugt, D.; Timpert, J.; Mierop, A.; de Haan, W.; Maes, W.; de Meulmeester, J.; Muhammad, W.; Dillen, B.; Stoldt, H.; et al. A Wafer-Scale CMOS APS Imager for Medical X-Ray Applications. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Image Sensor Workshop, Bergen, Norway, 25–28 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, I.; Das, D.; Guerrini, N.; Marsh, B.; Turchetta, R. LASSENA: A 6.7 Megapixel, 3-Sides Buttable Wafer-Scale CMOS Sensor Using a Novel Grid- Addressing Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Image Sensor Workshop, Snowbird, UT, USA, 12–16 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Blerkom, D.; Truong, L.; Rysinski, J.; Corlan, R.; Venkatesan, K.; Bagwell, S.; Oniciuc, L.; Bergey, J. A 1Mpixel, 80k Fps Global Shutter CMOS Image Sensor for High Speed Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Image Sensor Workshop, Online Event, 20–23 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchaert, T.; Ceulemans, B.; Wolfs, B.; Cotteleer, W.; Lepage, G.; Vanhorebeek, G.; Markey, E.; Huysman, A.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; et al. High Speed 21M Pixel Global Shutter Image Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Image Sensor Workshop, Online Event, 20–23 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Hansrani, J.; Bagwell, S.; Rytov, O.; Shah, V.; Ong, K.L.; Blerkom, D.V.; Bergey, J.; Kumar, N.; Lu, T.; et al. A 316MP, 120FPS, High Dynamic Range CMOS Image Sensor for Next Generation Immersive Displays. Sensors 2023, 23, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühlbrandt, W. The Resolution Revolution. Science 2014, 343, 1443–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RCSB PDB. PDB Statistics: Number of Released PDB Structures per Year. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/stats/all-released-structures (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Lavery, L. Cryo-EM Used in Novel Coronavirus Research to Support Vaccine, Treatment Development. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/blog/atomic-resolution/cryo-em-used-in-novel-coronavirus-research-to-support-vaccine-treatment-development/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Lynch, M.L.; Snell, E.H.; Bowman, S.E.J. Structural Biology in the Time of COVID-19: Perspectives on Methods and Milestones. IUCrJ 2021, 8, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruqi, A.R.; Henderson, R.; McMullan, G. Progress and Development of Direct Detectors for Electron Cryomicroscopy. In Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 190, pp. 103–141. ISBN 978-0-12-802380-8. [Google Scholar]

- Peet, M.J.; Henderson, R.; Russo, C.J. The Energy Dependence of Contrast and Damage in Electron Cryomicroscopy of Biological Molecules. Ultramicroscopy 2019, 203, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.M.; Courteau, B.J.; Maker, A.; Wu, M.; Basanta, B.; Mehmood, H.; Bulkley, D.; Joyce, D.; Lee, B.C.; Mick, S.; et al. High-Resolution Single-Particle Imaging at 100–200 keV with the Gatan Alpine Direct Electron Detector. J. Struct. Biol. 2024, 216, 108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karia, D.; Koh, A.F.; Yang, W.; Cushing, V.I.; Basanta, B.; Mihaylov, D.B.; Khavnekar, S.; Vyroubal, O.; Malínský, M.; Sháněl, O.; et al. Sub-3 Å Resolution Protein Structure Determination by Single-Particle Cryo-EM at 100 keV. Structure 2025, 33, 1717–1727.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durini, D. High Performance Silicon Imaging: Fundamentals and Applications of CMOS and CCD Sensors; Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Woodhead: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-85709-598-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bichsel, H. Straggling in Thin Silicon Detectors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1988, 60, 663–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dectris DECTRIS SINGLA Web Brochure. Available online: https://media.dectris.com/filer_public/25/87/25871486-5561-4af1-8ba5-6f28e9fa6871/singla_web_brochure_dectris_15_01.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Hutchings, S.W.; Larsen, H.; Sharkawy, M.E.; Sedgwick, I.; Marsh, B.; Starborg, T.; Barnard, J.; Hart, M.; Macwaters, C.; Vassilev, D.; et al. C100: A 4-Megapixel, 2000 FPS Wafer Scale Direct Electron Detection Sensor for 100keV Electron Cyro-Microscopy. In Proceedings of the C100: A 4-Megapixel, 2000 FPS Wafer Scale Direct Electron Detection Sensor for 100keV Electron Cyro-Microscopy, Bratislava, Slovakia, 8 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sannino, M.; Bofill-Petit, A.; Giulioni, M.; Mollà Garcia, A.; Turchetta, R.; McMullan, G.; Henderson, R.; Copetti, C.; Janssen, B.; Mele, L.; et al. A Rad-Hard, 60µm Pixel Sensor Optimized for the Direct Detection of Electrons. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Image Sensor Workshop, Online Event, 20–23 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, N.S.; Ancona, M.G.; Modolo, J.A. Radiation Effects in MOS Capacitors with Very Thin Oxides at 80°K. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1984, 31, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, M.; Bofill-Petit, A.; Pinaroli, G.; Turchetta, R. A High Dynamic Range, 1.9 Mpixel CMOS Image Sensor for X-Ray Imaging with In-Pixel Charge Binning and Column Parallel ADC. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Image Sensor Workshop, Snowbird, UT, USA, 23–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Bypass PGA | PGA X1 | PGA X2 | PGA X4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gain (DN/e−) | 8.78 | 7.33 | 16.38 | 33.33 |

| Linear Full Well (ke−) | 33.67 | 51.61 | 21.93 | 9.63 |

| Saturation Full Well (ke−) | 47.65 | 51.6 | 22.54 | 9.63 |

| Noise (e− rms) | 86.4 | 107.5 | 68.2 | 55.2 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Format | 2052 × 2064 pixels 4.2 megapixels |

| Illuminated | Front Side Illuminated (FSI) |

| Pixel size | 58 µm |

| Focal plane size | 119.0 mm × 119.7 mm |

| Noise | 86 e− rms |

| Linear full well | 33,700 e− |

| ADC | Column-parallel |

| ADC resolution (User-selectable) | 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 bits |

| Frame rate (At full 4.2 Mpixels resolution) | 7267 @ 4 bit 5768 @ 6 bits 5266 @ 8 bits 4542 @ 9 bits 3303 @ 10 bits |

| Frame rate (ROI: 2052 × 24) | 303,000 @ 8 bits 189,394 @ 10 bits |

| Frame rate (ROI: 2052 × 1056) | 6887 @ 8 bits 4304 @ 10 bits |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scott, A.; Bauzà, C.; Bofill-Petit, A.; Font, A.; Gargallo, M.; Gifreu, R.; Latif, K.; Mollà Garcia, A.; Sannino, M.; Turchetta, R. A 5000 Fps, 4 Megapixel, Radiation-Tolerant, Wafer-Scale CMOS Image Sensor for the Direct Detection of Electrons and Photons. Sensors 2026, 26, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020370

Scott A, Bauzà C, Bofill-Petit A, Font A, Gargallo M, Gifreu R, Latif K, Mollà Garcia A, Sannino M, Turchetta R. A 5000 Fps, 4 Megapixel, Radiation-Tolerant, Wafer-Scale CMOS Image Sensor for the Direct Detection of Electrons and Photons. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):370. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020370

Chicago/Turabian StyleScott, Andrew, Claus Bauzà, Adrià Bofill-Petit, Albert Font, Mireia Gargallo, Robert Gifreu, Kamran Latif, Armand Mollà Garcia, Michele Sannino, and Renato Turchetta. 2026. "A 5000 Fps, 4 Megapixel, Radiation-Tolerant, Wafer-Scale CMOS Image Sensor for the Direct Detection of Electrons and Photons" Sensors 26, no. 2: 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020370

APA StyleScott, A., Bauzà, C., Bofill-Petit, A., Font, A., Gargallo, M., Gifreu, R., Latif, K., Mollà Garcia, A., Sannino, M., & Turchetta, R. (2026). A 5000 Fps, 4 Megapixel, Radiation-Tolerant, Wafer-Scale CMOS Image Sensor for the Direct Detection of Electrons and Photons. Sensors, 26(2), 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020370