The Labeled Square Root Cubature Information GM-PHD Approach for Multi Extended Targets Tracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Our Work and Contribution

- (1)

- We present a labeled ET-GM-PHD approach based on the SRCIF method. First, we use a group of GM components to describe the density of the extended target. These GM components have been assigned different labels. Then, these labeled GM components have been predicted by the SRCIF method. Since the SRCIF method has been put forward for tracking standard targets, it cannot be directly applied to update the GM components of the extended targets. To solve such a problem, we have raised a candidate observation extracting method. With such a method, we can obtain the observations of each partition. Then, we implement the updating step of the SRCIF method to evaluate the updated labeled GM components. Using the updated components, we can obtain the posterior densities of multi extended targets. Benefiting from the above implementations, the tracking performance of the proposed approach can be significantly improved.

- (2)

- We present the state extracting method of our approach. Since we applied the labeled GM components for predicting and updating the density, GM components with the same label have a larger probability of being associated with the same target than the others. According to this, we first use the pruning method of the conventional ET-GM-PHD approach to discard the GM components with small weights. Thus, the number of GM components can be greatly decreased. Then, we derive the merging method to combine GM components with the same label. With the help of the preset threshold, these combined labeled components can be merged to extract the states of the multi extended targets.

- (3)

- The label-based trajectory constructing method has been proposed for constructing the trajectories of multi extended targets. In multi extended target tracking scenarios, affected by clutters, target detection loss, and death, the trajectory of a target may be broken into several pieces. To avoid such problems, we first divide the targets into four sets, such as, the survival, death, undetected, and unconfirmed sets. These sets can be used to describe the cases, such as target birth, survival, detection loss, and so on. Obviously, states with the same label at different time steps belong to the same target. Thus, we can assign the estimated states into the survival sets based on the label. When the labels of estimated states are not in the survival set, we present the label assignment strategy based on the gating method and trajectories. With such a strategy, the trajectories of extended targets can be steadily constructed.

2. The GM-PHD Approach for Extended Target Tracking

2.1. The PHD Filter for Extended Target Tracking

2.2. The GM-PHD Filter for Extended Target Tracking

- (1)

- Both the dynamic and observation models of the extended targets are subject to linear Gaussian models, represented bywhere denotes the Gaussian distribution, and and are the mean and covariance, respectively. is the transition matrix, and is the observation matrix.

- (2)

- The possibilities of target survival and detection are state independent,

- (3)

- The birth intensity is formulated by the GM components.where denotes the weight of the GM component, and and are the mean and covariance, respectively.

3. The LSRCI-GM-PHD Algorithm for Extended Target Tracking

3.1. The Labeled SRCIF-Based GM-PHD Method for Extended Target Tracking

3.1.1. Predict the State and Square Root Factor of the Covariance

3.1.2. Extract the Candidate Cells

3.1.3. Update Predicted States and Covariances

3.2. The State Extracting Method of the LSRCI-GM-PHD Approach

3.3. The Trajectory Constructing Method of the Proposed Approach

- (1)

- Assign the estimated states

- (2)

- Begin the trajectory

- (3)

- Matching the interrupted trajectories

3.4. Computational Complexity

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Simulation Scenarios

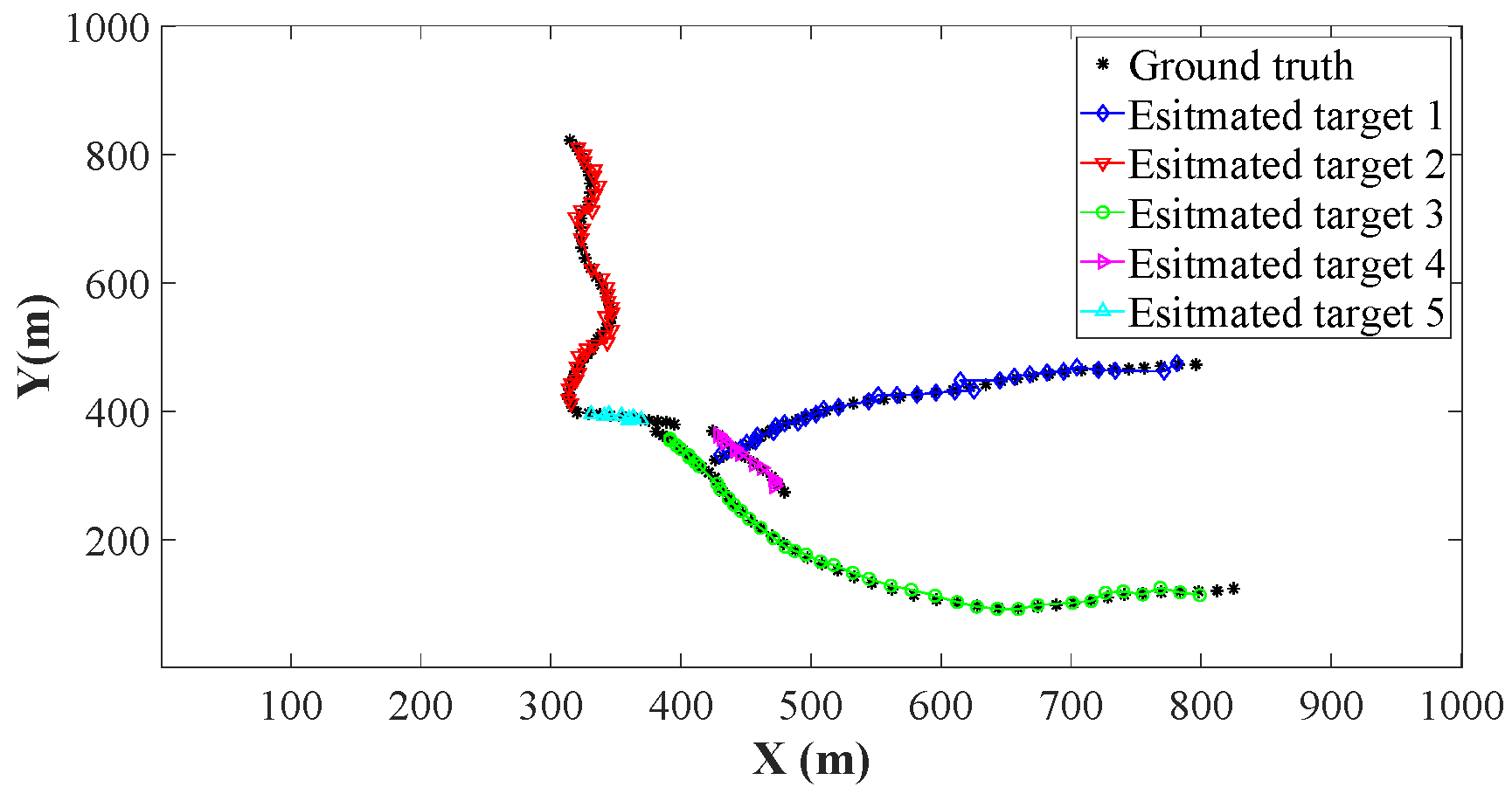

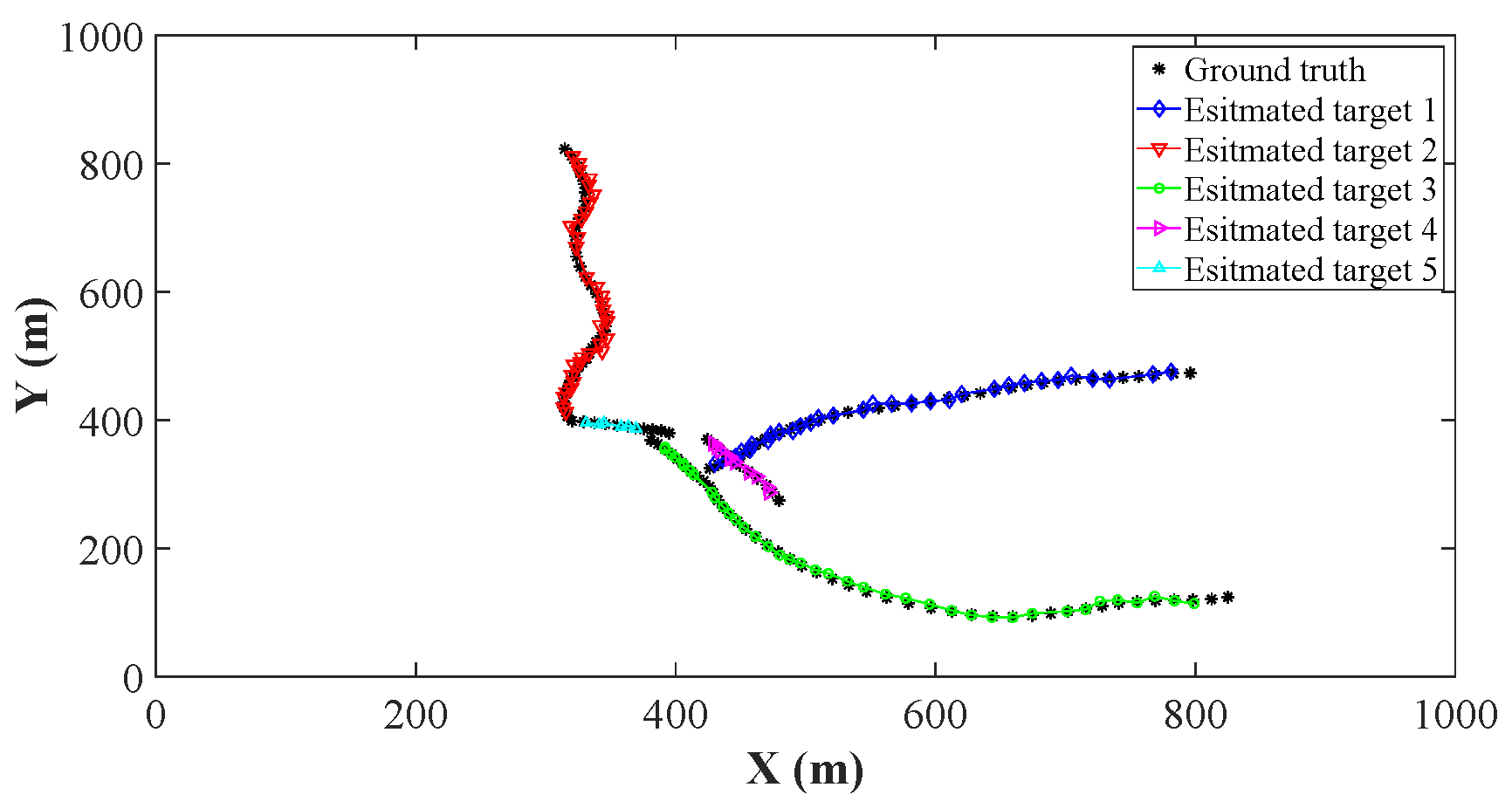

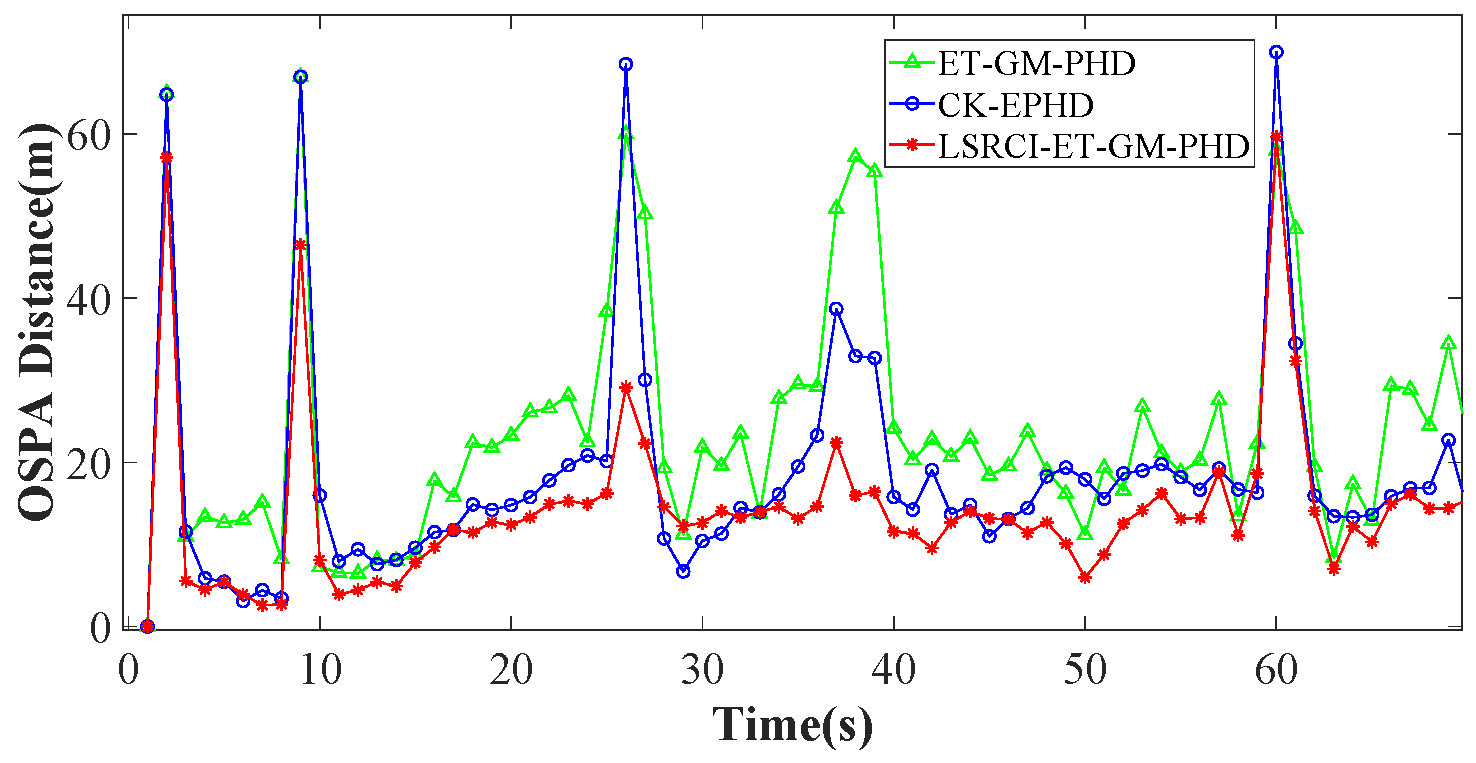

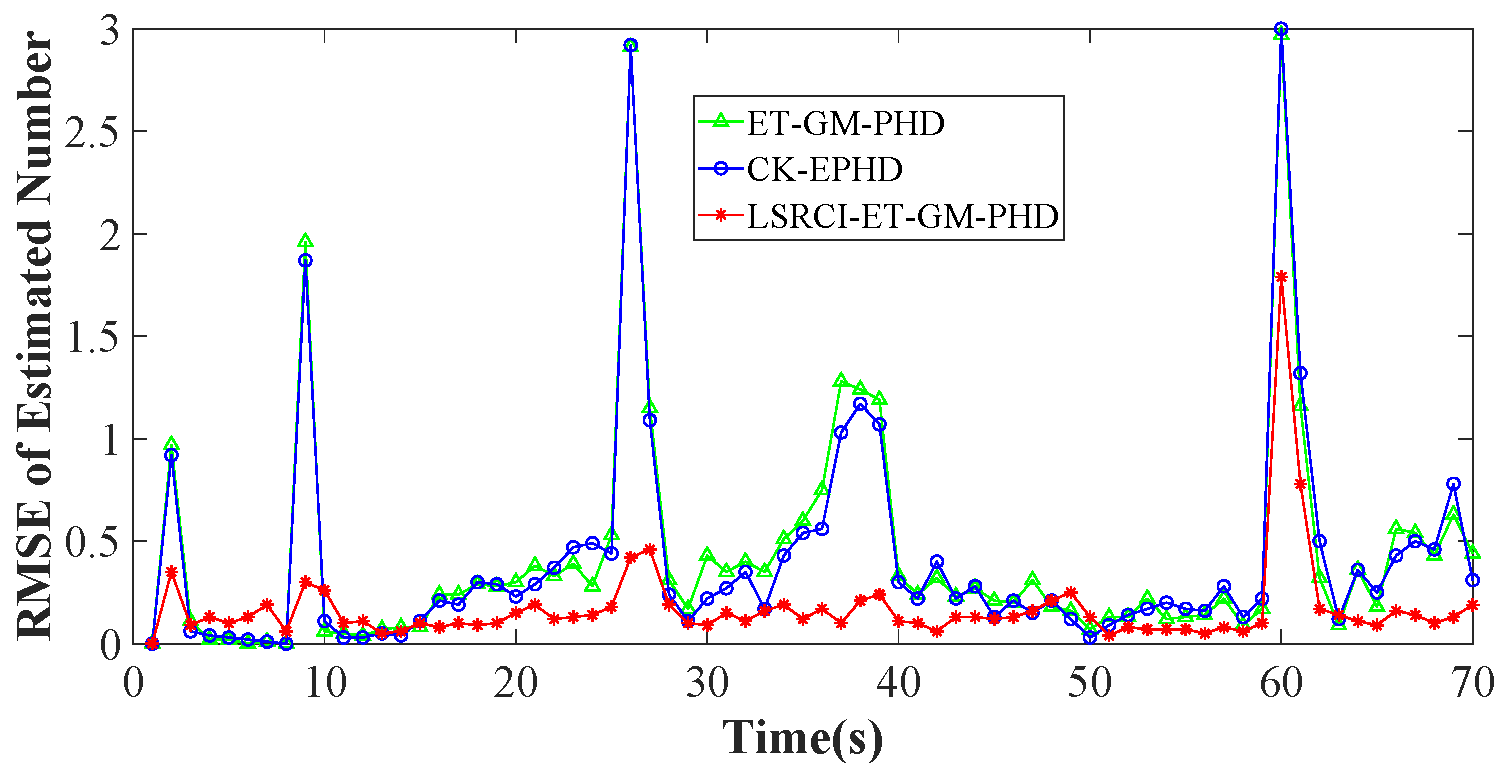

4.2. Comparison of Estimation Accuracy on a Certain Clutter Ratio

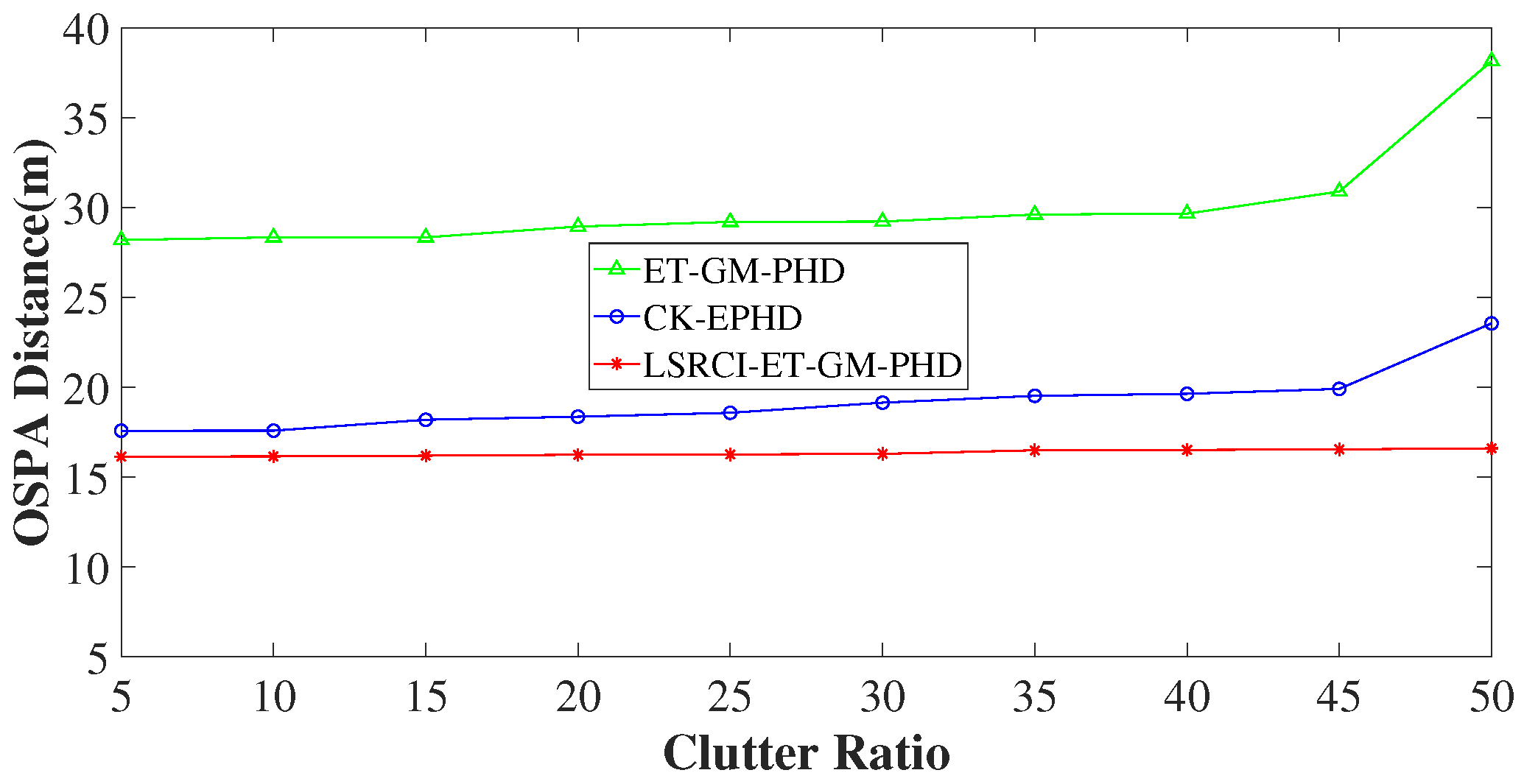

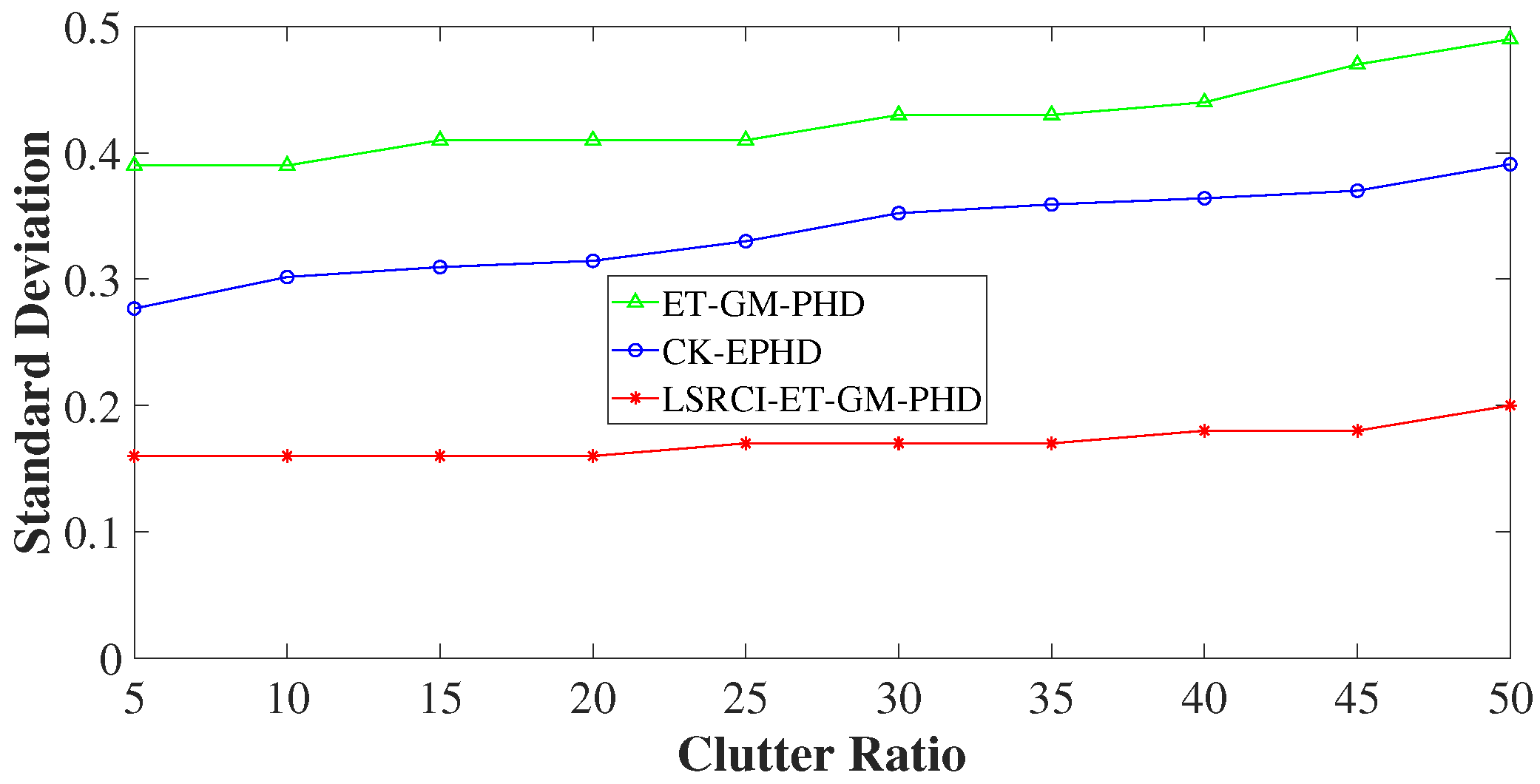

4.3. Comparison of Estimation Accuracy on Various Clutter Ratios

4.4. Comparison of Estimation Accuracy Under Different Detection Probabilities

4.5. Comparison of the Estimation Accuracy Under Different Survival Probabilities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHD | Probability hypothesis density |

| GM | Gaussian mixture |

| SRCIF | Square root cubature information filter |

| EPHD | Extended-target PHD filter |

| PMHT | Probabilistic multi-hypothesis tracker |

| VB | Variational Bayes |

| PMBM | Poisson multi-Bernoulli mixture |

| ET-GM-PHD | Extended target tracking using Gaussian mixture PHD |

| ART | Fuzzy adaptive resonance theory |

References

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, X.; Sun, G.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Y. Array Three-Dimensional SAR Imaging via Composite Low-Rank and Sparse Prior. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairui, S.; Ran, Z.; Huiyan, C.; Xiaodi, M.; Lin, L.; Jingya, Q. A review of point target and extended target tracking algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Image Processing and Media Computing (ICIPMC), Hefei, China, 17–19 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Granström, K.; Lundquist, C.; Orguner, U. A Gaussian Mixture PHD filter for Extended Target Tracking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Fusion, Edinburgh, UK, 26–29 July 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 915–921. [Google Scholar]

- Tuncer, B.; Özkan, E. Random matrix based extended target tracking with orientation: A new model and inference. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 1910–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ji, L.; Yang, F.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z.; Qin, D. Cubature Information Gaussian Mixture Probability Hypothesis Density Approach for Multi Extended Target Tracking. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 103678–103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Ren, H.; Zou, L.; Lin, J.; Zhou, Y. Attention-Based Maneuver-Aware Tracking Network for Maneuvering Target Tracking. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 2684–2688. [Google Scholar]

- Baomin, L.; Xiefan, P. Research on Maneuvering Target Tracking Algorithm Based on an Improved Particle Filter Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 OES China Ocean Acoustics (COA), Harbin, China, 29–31 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Deng, X.; Bu, S.; Jiang, M. Research on Maneuvering Target Tracking Algorithm with Adaptive Turning Rate Based on Dynamics Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Electronic Engineering and Informatics (EEI), Chongqing, China, 28–30 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1243–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Kong, L.; Yi, W.; Li, X. Robust Poisson multi-Bernoulli mixture filter with unknown detection probability. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 70, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M. Cubature information SMC-PHD for multi-target tracking. Sensors 2016, 16, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Ma, J.; Luo, Z. An Adaptive Multi-Bernoulli Filter for Coexisting Point Target and Extended Target Tracking with Unknown Detection Probability. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 84593–84606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, W.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, J.; Mao, H.; Yi, W. Clustering-Free Extended Target Tracking Method Based on Motion and Shape Information Feedback. In Proceedings of the 2025 28th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7–11 July 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, P.; Berntorp, K.; Svensson, L.; Granström, K.; Mansour, H.; Boufounos, P.; Orlik, P.V. Learning-Based Extended Object Tracking Using Hierarchical Truncation Measurement Model With Automotive Radar. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2021, 15, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, M.; Franken, D.; Koch, W. Tracking of extended objects and group targets using random matrices. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2011, 59, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Q.; Yang, X. Distributed Variational Measurement Update for Extended Target Tracking With Random Matrix. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 3792–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Z.; Jiao, Q. Variational Extended Target Tracking with Dependent Measurements Using Random Matrix. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14211–14226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, M.; Tharmarasa, R.; Kirubarajan, T. Seamless Tracking of Apparent Point and Extended Targets Using Gaussian Process PMHT. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2019, 67, 4825–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, K.; Fatemi, M.; Svensson, L. Poisson multi-Bernoulli mixture conjugate prior for multiple extended target filtering. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2019, 56, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, Á.F.; Williams, J.L.; Svensson, L.; Xia, Y. A Poisson multi-Bernoulli mixture filter for coexisting point and extended targets. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 2600–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhou, R. The multiple model Poisson multi-Bernoulli mixture filter for extended target tracking. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 14304–14314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, R. PHD filters for nonstandard targets, I: Extended targets. In Proceedings of the 2009 12th International Conference on Information Fusion, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–9 July 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 915–921. [Google Scholar]

- Granstrom, K.; Orguner, U. A phd Filter for Tracking Multiple Extended Targets Using Random Matrices. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 5657–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Cui, C.; Wu, B. A GGIW-PHD Filter for Multiple Non-Ellipsoidal Extended Targets Tracking with Varying Number of Sub-Objects. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 64719–64731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrom, K.; Lundquist, C.; Orguner, O. Extended target tracking using a Gaussian-mixture PHD filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 3268–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Xu, N.; Xu, L.; Li, M.Q.; Cheng, P. An improved partitioning algorithm based on FCM algorithm for extended target tracking in PHD filter. Digit. Signal Process. 2019, 90, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, N.; Ma, L.; Xu, B. Extended target probability hypothesis density filter based on cubature Kalman filter. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2015, 9, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Yao, X.; Sun, J.; Shan, T. Gaussian Process Gaussian Mixture PHD Filter for 3D Multiple Extended Target Tracking. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Kirubarajan, T.; Liang, Y. Application of an Efficient Graph-Based Partitioning Algorithm for Extended Target Tracking Using GM-PHD Filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 4451–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Ji, H. Multiple Extended Target Tracking Using PHD Filter and Convolutional Conditional Neural Process. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems (ICAUS 2022), Xi’an, China, 23–25 September 2022; Volume 1010, pp. 2424–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, R.; Ni, N.; Dou, L.; Hu, C. A Gaussian Mixture PHD Filter for Multitarget Tracking in Target-Dependent False Alarms. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 4808–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tian, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, W.; Yi, W. Trajectory PHD Filter for Extended Traffic Target Tracking with Interaction and Constraint. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Venice, Italy, 8–11 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, H. A robust and fast partitioning algorithm for extended target tracking using a Gaussian inverse wishart PHD filter. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 95, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Bar-Shalom, Y.; Kirubarajan, T. Track labeling and PHD filter for multitarget tracking. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2006, 42, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Hu, W.; Kirubarajan, T. Labeled Random Finite Sets With Moment Approximation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 3384–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Zhang, B.; Yang, J.; Long, X.; Peng, C.; Yi, W. Labeled Probability Hypothesis Density Filtering for Track-Before-Detect Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Charleston, SC, USA, 27–30 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gilholm, K.; Godsill, S.; Maskell, S.; Salmond, D. Poisson models for extended target and group tracking. In Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets 2005; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; Volume 5913, pp. 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, K.P.B.; Gu, D.W.; Postlethwaite, I. Square Root Cubature Information Filter. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 750–758. [Google Scholar]

- Arasaratnam, I.; Haykin, S. Cubature Kalman Filters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2009, 54, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, B.N.; Ma, W.K. The Gaussian Mixture Probability Hypothesis Density Filter. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 4091–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmathullah, A.S.; García-Fernández, Á.F.; Svensson, L. Generalized optimal sub-pattern assignment metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th International Conference on Information Fusion (Fusion), Xi’an, China, 10–13 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.H.; Kim, D.U.; Yoon, K.J. Gaussian mixture importance sampling function for unscented SMC-PHD filter. Signal Process. 2013, 93, 2664–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

| Target | State | Appearing (s) | Disappearing (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 40 | |

| 2 | 8 | 50 | |

| 3 | 25 | 70 | |

| 4 | 59 | 70 | |

| 5 | 59 | 70 |

| Approach | OSPA (m) | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| ET-GM-PHD | 29.23 | 0.43 |

| CK-PHD | 17.29 | 0.25 |

| LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | 16.19 | 0.17 |

| ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | |

| OSPA (m) | 35.80 | 21.09 | 18.49 | 29.56 | 18.77 | 16.54 |

| RMSE | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.18 |

| ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | |

| OSPA (m) | 28.25 | 17.13 | 15.93 | 28.13 | 16.59 | 15.84 |

| RMSE | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.16 |

| ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | |

| OSPA(m) | 36.80 | 22.12 | 17.35 | 30.12 | 20.73 | 15.52 |

| RMSE | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.17 |

| ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | ET-GM-PHD | CK-EPHD | LSRCI-ET-GM-PHD | |

| OSPA (m) | 29.53 | 17.60 | 14.92 | 29.27 | 17.62 | 14.84 |

| RMSE | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Qu, X.; An, J. The Labeled Square Root Cubature Information GM-PHD Approach for Multi Extended Targets Tracking. Sensors 2026, 26, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020367

Liu Z, Zhang S, Yang Z, Qu X, An J. The Labeled Square Root Cubature Information GM-PHD Approach for Multi Extended Targets Tracking. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020367

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhe, Siyu Zhang, Zhiliang Yang, Xiqiang Qu, and Jianping An. 2026. "The Labeled Square Root Cubature Information GM-PHD Approach for Multi Extended Targets Tracking" Sensors 26, no. 2: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020367

APA StyleLiu, Z., Zhang, S., Yang, Z., Qu, X., & An, J. (2026). The Labeled Square Root Cubature Information GM-PHD Approach for Multi Extended Targets Tracking. Sensors, 26(2), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020367