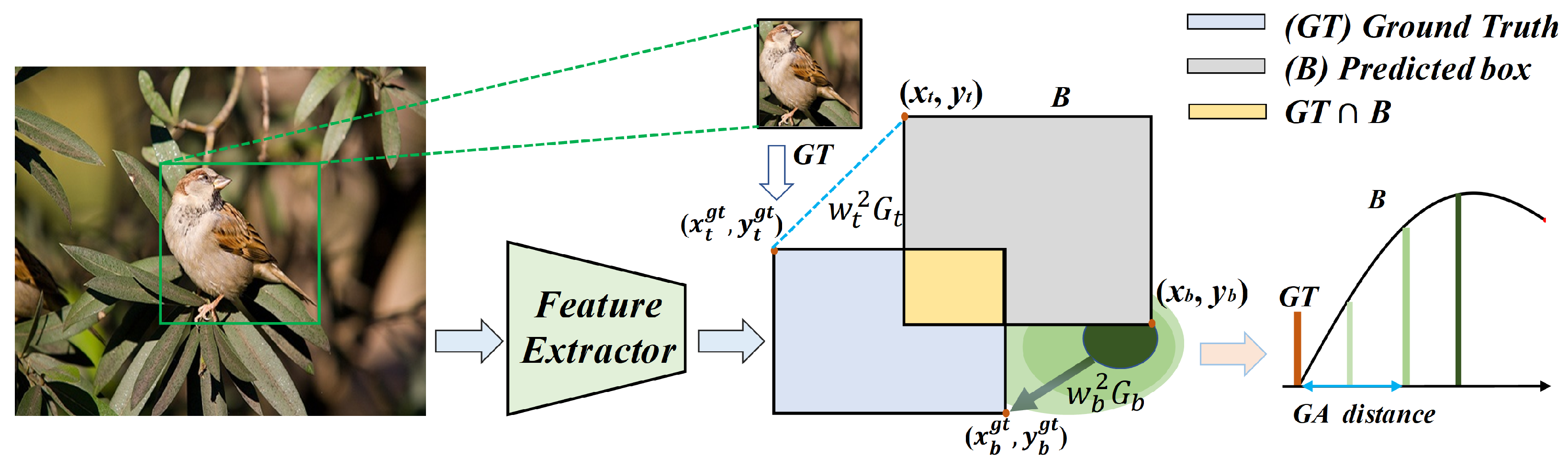

The objective of this study is to enhance the ability of object detection algorithms to accurately identify objects of diverse sizes and shapes. To this end, we propose the Gaussian Adaptive BBR Loss (GAOC), a novel loss function specifically designed to optimize localisation and classification in object detection. By integrating GAOC into the YOLOv5 and RT-DETR object detection frameworks and conducting extensive experiments on the PASCAL VOC and MS COCO 2017 benchmark datasets, we demonstrate that GAOC achieves superior performance in multi-scale object detection tasks.

4.1. MS COCO 2017 and PASCAL VOC

The Common Objects in Context (COCO) dataset is a large-scale benchmark developed by Microsoft in collaboration with research institutions. It contains over 330,000 images featuring diverse objects and complex backgrounds and is widely used for computer vision tasks such as object detection, semantic segmentation, and instance-level annotation. Each image is annotated with precise bounding boxes, pixel-level segmentation masks, and corresponding semantic labels. The COCO dataset defines 80 object categories, covering common classes such as humans, animals, and vehicles, while also providing scene-level annotations for background contexts. In the COCO 2017 release, the Train2017 subset (118,287 images) is used for model training, the Val2017 subset (5000 images) for validation, and the Test2017 subset (20,288 images) for performance evaluation and benchmarking.

The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (PASCAL VOC) dataset is a widely used benchmark for object detection, image classification, and semantic segmentation. In this study, the VOC2007 and VOC2012 datasets are integrated to form a combined training set of 21,503 images and a test set of 4952 images, covering a total of 20 object categories.

4.3. Experimental Analysis

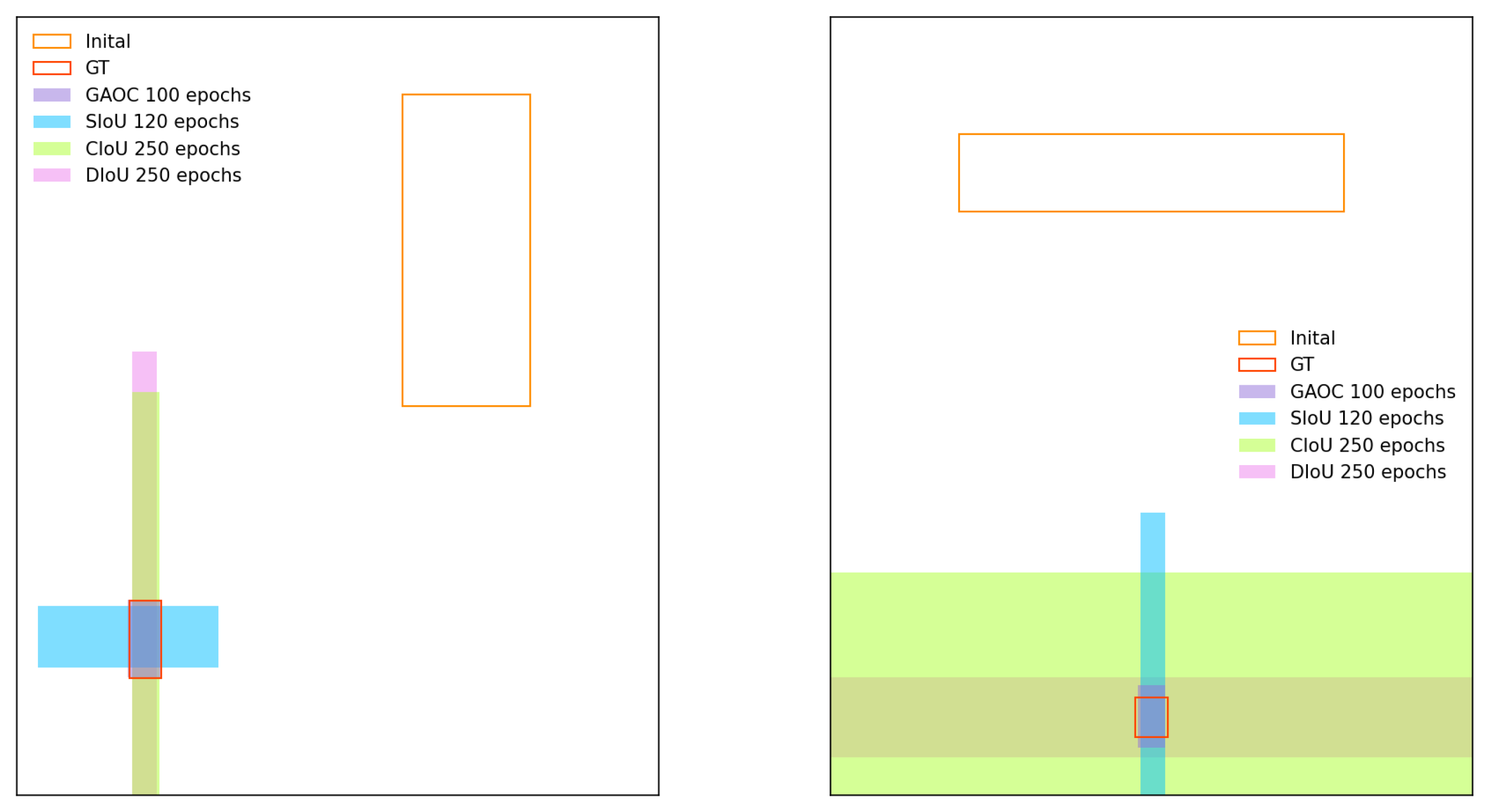

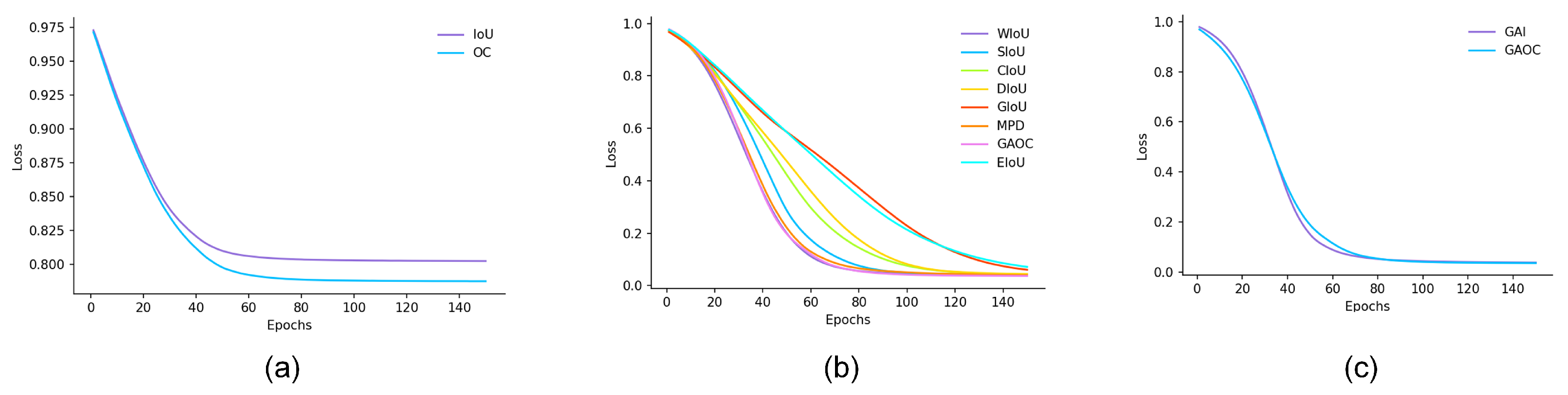

As shown in

Figure 5a, under identical initialization conditions, both IoU and OC losses decrease monotonically as training iterations increase, and they reach a plateau after about 50 to 70 epochs, reflecting the stability of the overall optimization process. However, the two curves ultimately converge to loss levels of 0.804 and 0.788, indicating that their localization performance remains limited. By contrast, the OC loss demonstrates a faster descent and a lower convergence value, implying that in cases of minor overlaps or partial scale mismatches, OC provides smoother gradients and thus achieves more effective loss suppression. These results reveal that relying solely on intersection-based metrics (IoU or OC) is insufficient to provide adequate geometric guidance in scenarios with large displacements or significant shape differences.

Based on the results in

Figure 5b,c and

Table 1, we systematically compared multiple BBR loss functions. As shown in

Figure 5b,c, all methods exhibit a stable downward trend in their training curves. However, they differ significantly in convergence speed and final residual values. In terms of curve morphology, WIoU, SIoU, and GAOC decline most rapidly within the 40 to 60 epochs and quickly enter a low loss plateau. GIoU converges the slowest and retains the highest residual error. EIoU descends faster in the mid-to-late training phase but still ends with relatively high residuals. A closer comparison between GAOC (GA + OC) and GAI (GA + IoU) shows that both follow a smooth, S-shaped convergence trajectory. GAOC achieves a lower final value and a more stable plateau. This suggests that it provides effective gradient guidance in both the early geometric alignment and the later fine-tuning stages of localization.

From

Table 1,

represents the overall average localization quality, whereas

reflects the lower bound performance on the most challenging samples. Higher values indicate greater robustness. GAOC achieves the best results on both

(0.963) and

(0.956). This demonstrates improvements not only in overall accuracy but also in worst-case long tail performance. GAI (0.959/0.953) yields comparable results. WIoU achieves a higher

(0.950) than MPDIoU (0.942), indicating stronger robustness. DIoU and CIoU perform at moderate levels. EIoU shows competitive average performance (0.958) but a very low

(0.51), revealing high vulnerability to long tail cases. GIoU performs the weakest across both metrics (0.872/0.571).

Mechanistically, GAOC and GAI integrate overlap measures with Gaussian corner-based geometric constraints. These constraints yield nonvanishing, directionally informative gradients even under zero overlap and weak overlap conditions. This design enables fast convergence, low residual loss, and strong long tail robustness. WIoU mitigates noisy gradient effects through hard sample adaptive weighting, thereby stabilizing its tail performance. In contrast, EIoU suffers from gradient imbalance when dealing with extreme shapes and large displacements. This results in degraded tail performance. In summary, GAOC achieves the best overall performance in this simulation study, excelling in convergence speed, final accuracy, and long tail robustness.

Table 2 and

Table 3 present the experimental results on the COCO 2017 and PASCAL VOC datasets, respectively. A comparison of different BBR losses (including CIoU, DIoU, EIoU, GIoU, SIoU, WIoU, and MPDIoU) against GAOC yields the following conclusions. On the COCO 2017 dataset, GAOC outperformed all competing methods in mAP, mAP75, and mAP50. Specifically, GAOC achieved an mAP of 46.2%, representing a 1.6% improvement over the best-performing competitor, WIoU (44.6%), thereby demonstrating a clear advantage in detection accuracy. GAOC also achieved an mAP50 of 64.5%, corresponding to a 3.2% increase over WIoU and substantial improvements compared to other methods.

On the PASCAL VOC dataset, GAOC achieved an mAP50 of 79.0%, further confirming its superior performance. The consistent improvements across both datasets highlight GAOC’s robust generalization capability: it sustains high detection accuracy in the complex, real-world scenes of COCO 2017 as well as in the standardized image settings of PASCAL VOC.

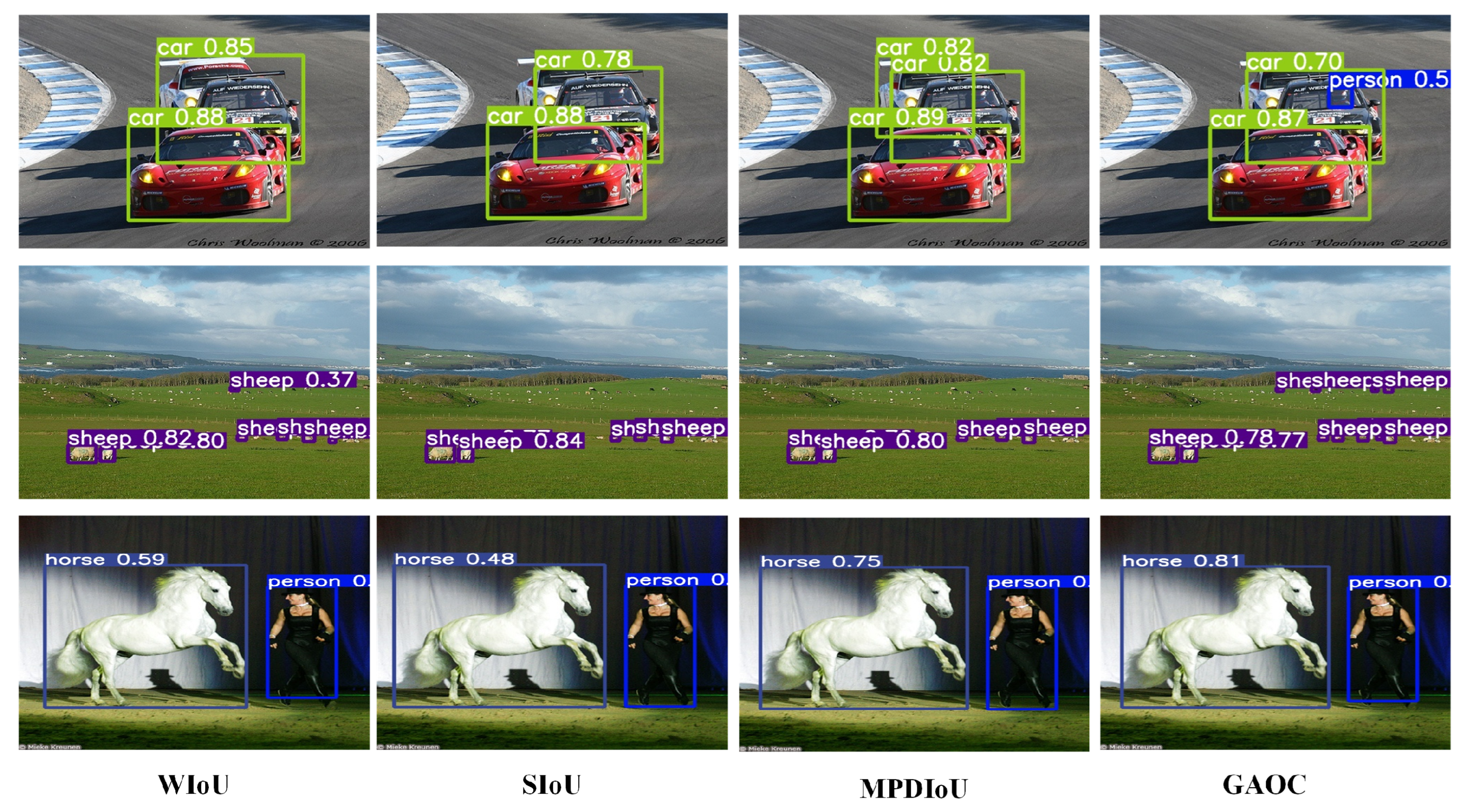

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate qualitative detection results, further supporting the superior performance of GAOC compared with alternative loss functions.

Table 4 presents the performance of various BBR losses functions on the MS COCO dataset using RT-DETR as the baseline, with GAOC demonstrating clear advantages across key evaluation metrics. For the mAP50 metric, GAOC achieved the highest score of 65.3%, surpassing the second-ranked CIoU (64.9%) by 0.4%. This result indicates that GAOC delivers superior object detection accuracy under relaxed matching criteria. GAOC also maintained the leading position in mAP, achieving a score of 47.8%. Overall, in experiments on the MS COCO dataset with RT-DETR as the benchmark, GAOC consistently outperformed other mainstream BBR losses functions (including CIoU, DIoU, and EIoU) across both mAP50 and mAP metrics. These findings confirm that GAOC more effectively optimizes BBR in object detection, improves detection accuracy, and provides superior overall performance.

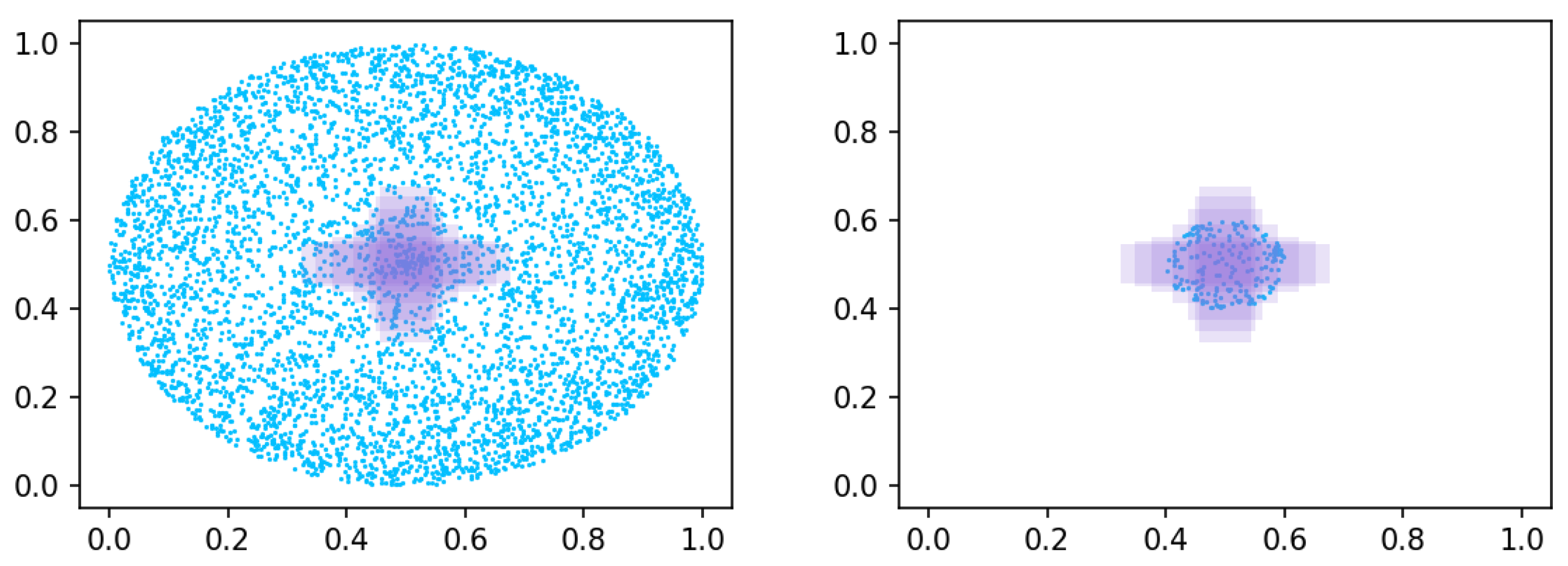

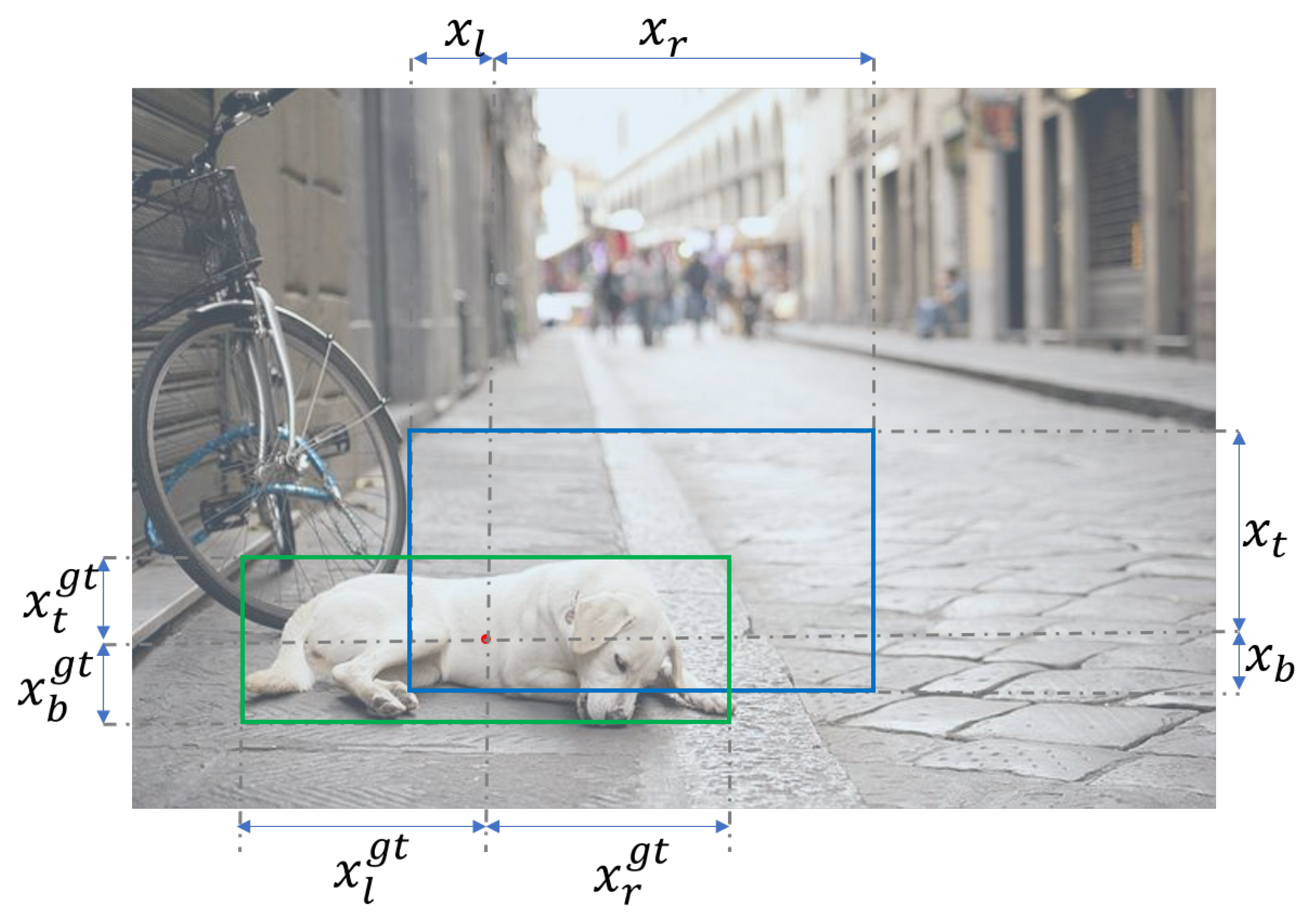

The design philosophy of GAOC is grounded in a deep understanding of the intrinsic characteristics of the BBR problem. By introducing a falloff coefficient, GAOC assigns greater weight to the intersection between predicted and ground truth boxes in the loss function, thereby improving detection performance for multi-scale objects. In addition, the incorporation of a Gaussian adaptive mechanism increases the algorithm’s robustness to variations in target position by modeling the TL/BR coordinates of bounding boxes as a two-dimensional Gaussian distribution.

Synthesizing the experimental results with the methodological analysis, we conclude that the GAOC loss function demonstrates outstanding performance in object detection tasks. The combination of its innovative design and consistent empirical outcomes validates GAOC as a novel BBR loss function with significant potential to advance the field of object detection. Future research could explore applying GAOC to diverse scenarios and tasks, as well as integrating it with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) algorithms.

4.4. Ablation Study

When comparing the OC and IoU loss functions, as shown in

Table 5, OC consistently outperforms IoU across both mAP50 and mAP. By normalizing the square root of bounding box dimensions’ product, OC achieves scale invariance and enables more accurate similarity measurement between predicted and ground truth boxes, thereby delivering superior performance in object detection tasks.

The comparison between GAI and GAOC shows that GAOC surpasses GAI by 1.2% and 0.5% in mAP50 and mAP, respectively. This result validates the rationale for integrating GA with OC. The GA mechanism reduces sensitivity to positional deviations by modeling the TL/BR coordinates of bounding boxes as a two-dimensional Gaussian distribution. The scale invariance of OC further complements this approach. In contrast, GAI’s reliance on IoU limits its optimization capacity, and even when combined with GA, it fails to match the comprehensive performance of GAOC. These findings suggest that GAOC adopts a more effective design strategy for BBR optimization, better addressing the challenges of complex scenes and multi-scale object detection.