1. Introduction

Affine image transformation, a fundamental geometric transformation in computer vision and image processing, is critical for establishing spatial correspondence between image pixels [

1]. It encompasses core operations such as rotation, translation, scaling, and shearing, enabling flexible adjustment of image geometry while preserving the collinearity and parallelism of the pixels [

2,

3,

4]. Affine transformation is widely employed in image registration, fusion, and correction, with applications in remote sensing, medical imaging, and autonomous driving [

5,

6]. In real-time video fusion, affine transformation facilitates the registration of multispectral images [

7]. In panoramic stitching, the alignment of overlapping regions is supported [

8]. These applications underscore their role as the cornerstones of modern image processing.

The image correction process involves three key steps. These steps include determining the corresponding point pairs, calculating the affine transformation matrix, and performing affine transformation-based image interpolation [

9]. The final step is the core of affine transformation. This step is highly computationally intensive as it involves trigonometric functions, matrix multiplication and interpolation. In image registration tasks, it dominates up to 85% of the total central processing unit (CPU) execution time [

10]. Thus, latency reduction is essential for real-time performance in intensive image-processing tasks. FPGAs offer several advantages, including low latency, low power consumption, and high system flexibility [

11]. These features have motivated extensive research in this area [

12,

13,

14]. However, FPGAs have certain limitations, including constrained on-chip resources. Moreover, adapting to new usage scenarios typically requires a hardware redesign.

Previous studies have sought to improve affine transformation efficiency through both algorithmic optimization and hardware acceleration techniques [

15,

16]. In the inseparable implementation method, the coordinate rotation digital computer (CORDIC) algorithm was used to design dedicated chips for implementing image rotation applications [

17,

18]. Although this algorithm does not require multiplication operations, the hardware requirements are higher, and the initial delay of the CORDIC is also higher. In the study by Bhandakar and Yu, an image rotation implementation method based on lookup tables (LUT) was reported, in which two independent LUTs were used to store the sine and cosine values for calculating the pixel positions in the image [

19]. Owing to the movement of the center position of the image, each pixel position has a corresponding position in the image. In the study by Biswal and Banerjee, the proposed ATPR algorithm leverages the repetitive nature of pixel positions to perform parallel computations for the transformation of two pixel positions [

20]. Biswal et al. proposed a modified ATPR (MATPR) algorithm that can calculate the transformation of four pixel positions through a single transformation operation [

21]. Affine transformation by removing multiplications (ATRM) eliminates multiplications by leveraging the relationships between neighboring pixels but incurs significant overheads due to slow image data access speeds [

22,

23]. However, ATRM suffers from slow data access, and block methods often incur high bus loads because of the noncontiguous output addresses.

Hardware accelerators dedicated to affine transformations are typically implemented exclusively on FPGA. The exceptional parallel processing capability inherent to FPGA facilitates the concurrent computation of multiple pixel points throughout the affine transformation process. However, for complex systems, relying solely on FPGAs is insufficient to meet all task requirements. SoC architectures are more adept at performing system control-oriented tasks [

24,

25]. However, during the execution of an affine transformation, the SoC requires access to double data rate (DDR) memory via an advanced extensible interface (AXI), which leads to a decrease in the efficiency of the affine transformation operation [

26]. Belokurov used high-level synthesis (HLS) to deploy affine transformations, with the process also utilizing the AXI interface and DMA [

27]. Although the block data are successfully read, the writing process is still carried out address by address, which leads to a decrease in efficiency.

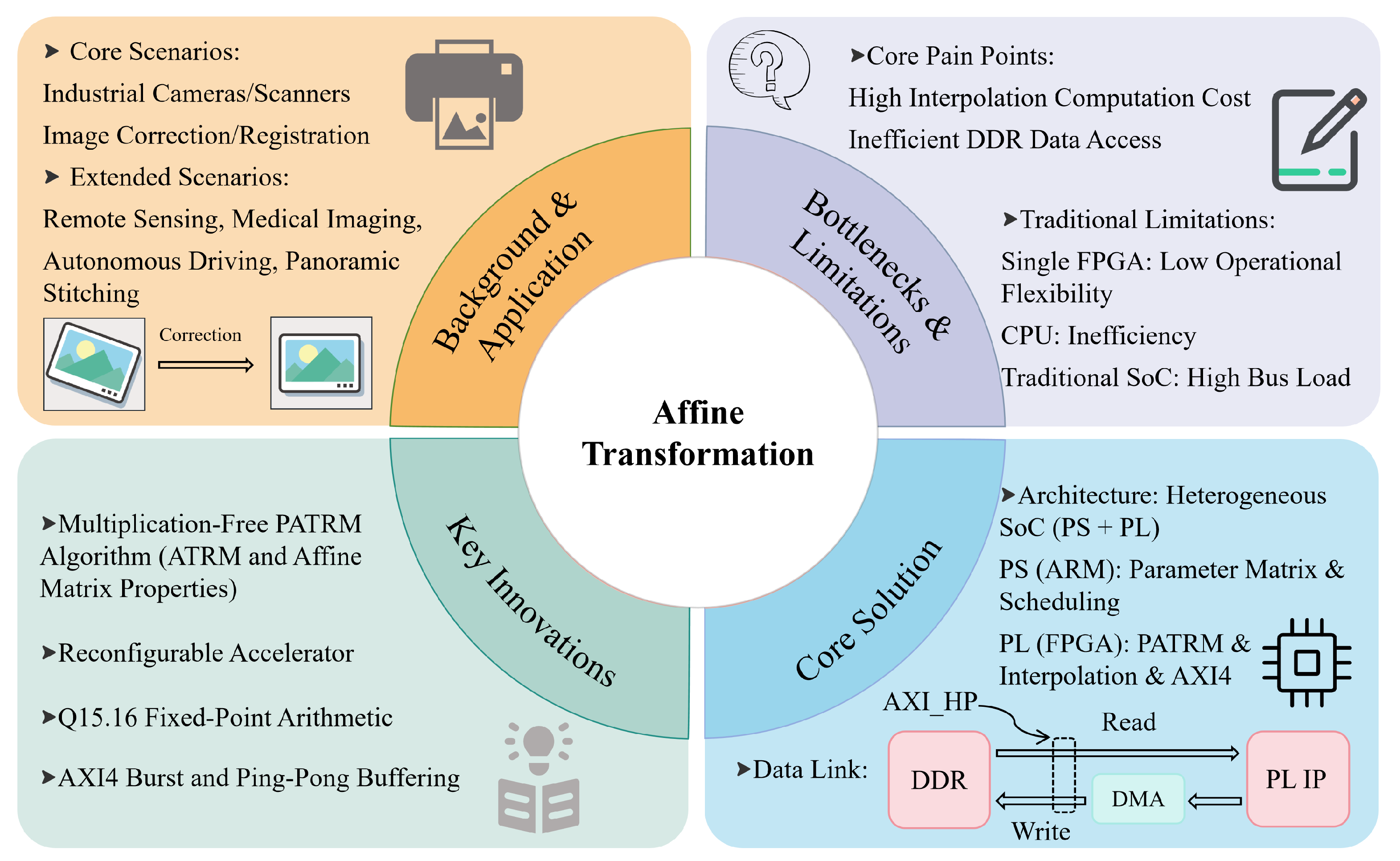

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed solution to the bottlenecks of traditional affine transformation methods. We propose a heterogeneous SoC-based accelerator for affine transformation using FPGA technology. The architecture decouples the computation into control and data paths. The ARM in the PS handles control tasks (scheduling and parameter matrix generation), whereas the FPGA in the PL implements the proposed prefetch ATRM (PATRM) algorithm. PATRM integrates the multiplication-free method of ATRM with affine matrix properties, and AXI4 burst transmission optimizes DDR access for efficient prefetching and pipelined processing. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed architecture achieves twice the throughput of the conventional solutions. The system meets the real-time requirement of 25 FPS for

image processing while providing computational determinism and maintaining system reconfigurability.

3. Hardware Design

3.1. System Architecture

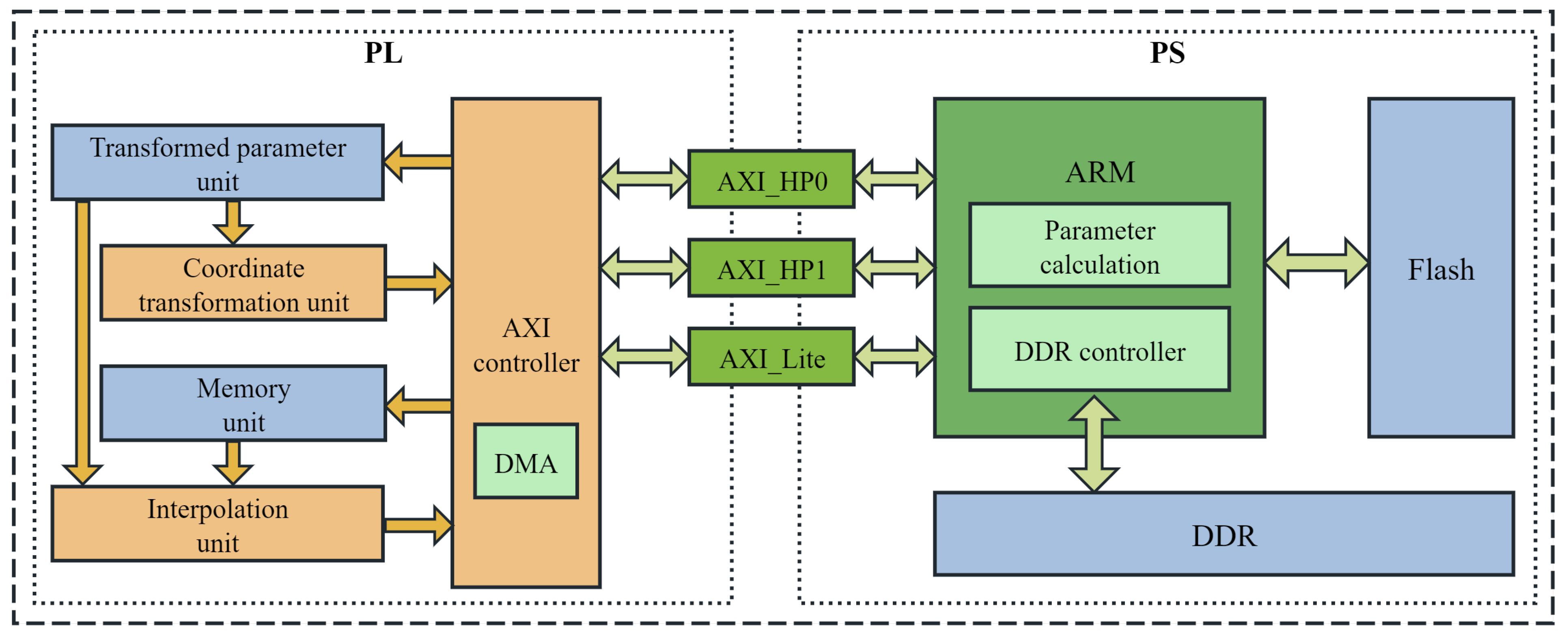

A block diagram of the accelerator system is shown in

Figure 4. The pipelined computation of the affine transformation, which is the core of the entire hardware accelerator, handles the pixel prefetching and interpolation. Efficient block data prefetching is achieved through AXI4 burst transmission, where contiguous pixel rows in the source image are read in advance based on the calculated

range. In data transmission, PATRM executes only one read and one write operation per data block. In contrast, Block AT typically performs one read followed by multiple writes. This single read-write scheme reduces the total number of DDR accesses, which aligns with the spatial locality exploited by PATRM.

The PL section incorporates four core computational Intellectual Property (IP) blocks, including the transformed parameter unit, coordinate transformation unit, memory unit, and interpolation unit. These units are pipelined based on the pixel data flow. The AXI controller manages the initialization of the parameters and distribution of tasks to the computational units. A Direct Memory Access (DMA) controller handles high-speed data transfer between the PL (FPGA) and PS (ARM core). Specifically, the DMA controller reads the source images from the DDR and writes the transformed images to the DDR. The PS primarily consists of an ARM processor, DDR memory, and a flash storage. The affine transformation matrices are stored in flash memory, and the ARM processor orchestrates the entire transformation process.

During global data scheduling within the system, data communication between the PS and PL is achieved through two AXI_HP interfaces and one AXI_Lite interface. In our implementation, the transformation matrix and image information are first written to the transformation parameter unit using the AXI_Lite interface. Once the configuration was complete, a start command was given. The coordinate transformation unit then calculates and reads the address information. Subsequently, the pixels were stored in the RAM-based memory unit through the AXI_HP interface. Finally, the interpolation unit completed the interpolation. The DMA transfers the processed pixels back to the DDR through AXI_HP interface.

3.2. Hardware Module Design

The design of the PL portion of the system was divided into two main components. The first component comprises the control and configuration paths. It is primarily responsible for system scheduling and parameter configuration of various modules, such as the affine matrices and image data. The second component is the data path. It encompasses the computational process of affine transformation from an input image to an output image.

During the affine transformation process, the transformed parameter unit uses several registers to cache the configuration parameters from the PS and forward the commands. The key parameters include the image storage address, image information, and the start and stop commands. Once the configuration information is ready, a start command is issued. The transformation parameter unit loads various parameters into the downstream units to initiate an affine transformation process. Affine transformations of images of different sizes can be performed using a dynamic parameter configuration.

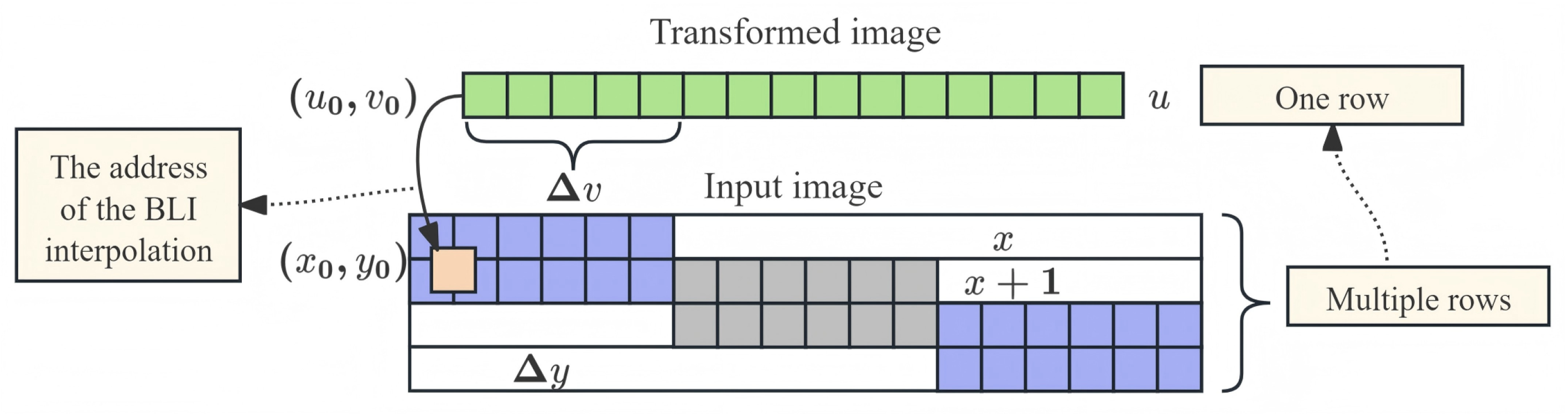

After the start command is received, the coordinate transformation unit converts the position of the target pixel to the corresponding position of the source pixel. It cooperates with the AXI controller to complete the reading of pixel data, as shown in

Figure 5. The initial coordinates of the source pixel were calculated using the proposed PATRM algorithm. The system then uses a burst transmission mechanism to read the gray values of the pixels in the same source row into memory units. Based on the row and column positions of the current output image, an affine transformation matrix was used to calculate the position of the input image. A three-stage pipeline was adopted to complete these calculations and accelerate the operating frequency. The read address of the DDR is jointly determined by the base address and coordinates.

With traditional DDR reading methods directly deployed on an FPGA using serial computing hardware platforms, different addresses in the DDR are accessed frequently. This not only wastes hardware resources but also limits the execution speed of the hardware. The proposed PATRM determines the burst-transmission length. It can simultaneously read multiple pixels. Data read from the DDR are stored in the RAM through a selector for interpolation calculations. In the interpolation process, the data were written to RAM1 for interpolation calculations. Meanwhile, PATRM predicts the next burst transmission address using and . The read data were then written to RAM2. Subsequent operations were performed using a ping-pong mechanism.

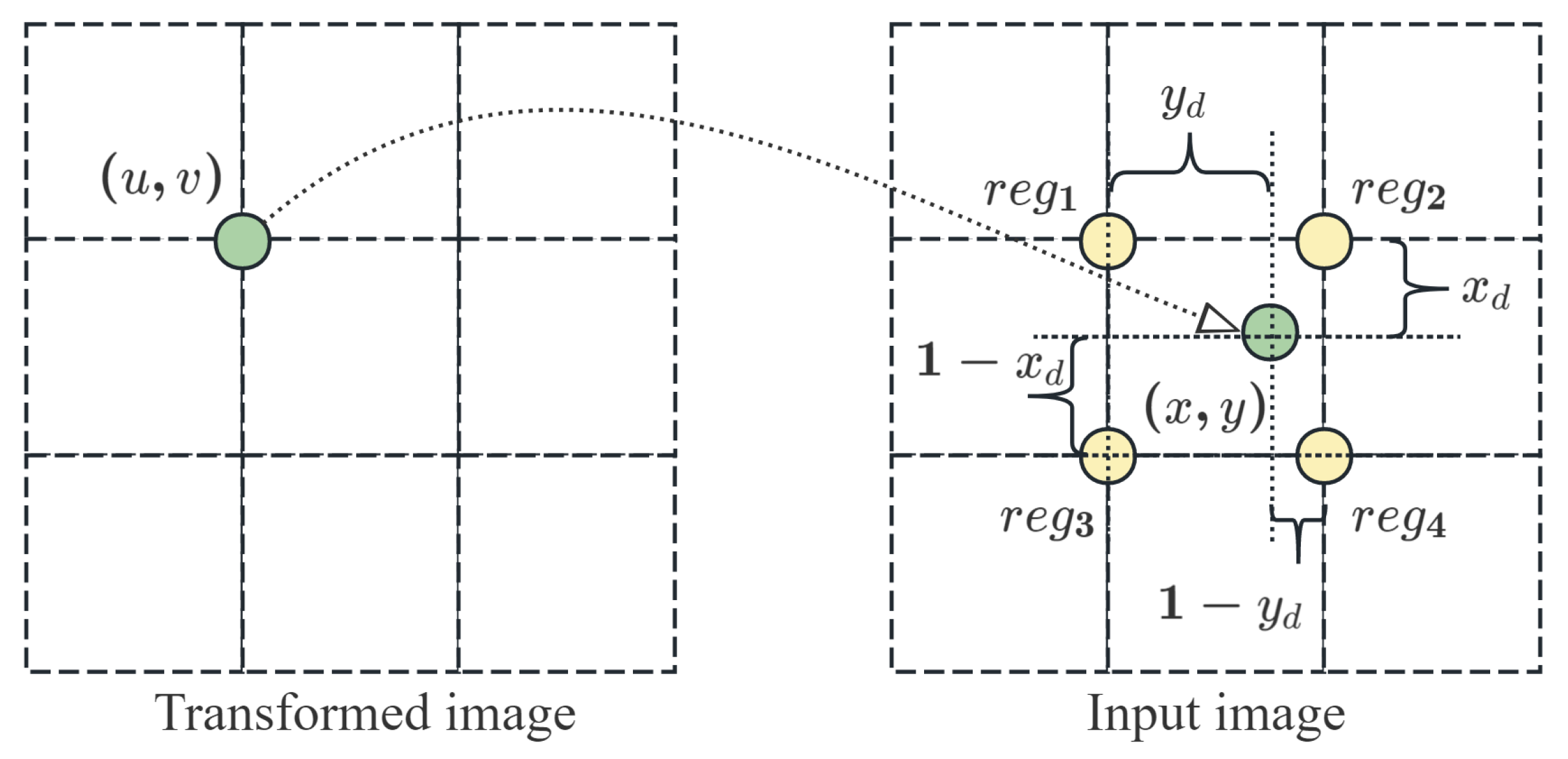

When the data are stored in the memory unit, the coordinate transformation unit performs interpolation. The interpolation calculation process is illustrated in

Figure 6. The process of calculating the pixel values also adopts a four-stage pipeline. The interpolation weights for the four pixels were determined using the fractional component

calculated by the coordinate transformation unit. The data read from the RAM underwent interpolation. To reduce the computational complexity, the pipeline truncates the data-bit width. Because the pixel data are integers, truncating the fractional part introduces a negligible error while significantly increasing the operating speed. The interpolated result

D is initially buffered in the FIFO. Upon reaching the maximum burst length, the FIFO contents were written to the specified location in the DDR using the AXI_HP interface.

4. Experimental

The complete algorithm verification process is illustrated in

Figure 7. The feasibility of the algorithm was ensured by using C++ 17 to implement OpenCV, floating, and fixed PATRM for cross-validation. The results showed that the proposed PATRM can perform image affine transformations. Subsequently, the quantified PATRM was implemented using Verilog HDL and deployed on the designated platform for simulation and hardware deployment. This algorithm verification process, which started with software and progresses through simulation to hardware, ensured the accuracy of the algorithm results. The test images included a

photographer image and a series of images, all represented by 256 grayscale levels.

4.1. Simulation Results

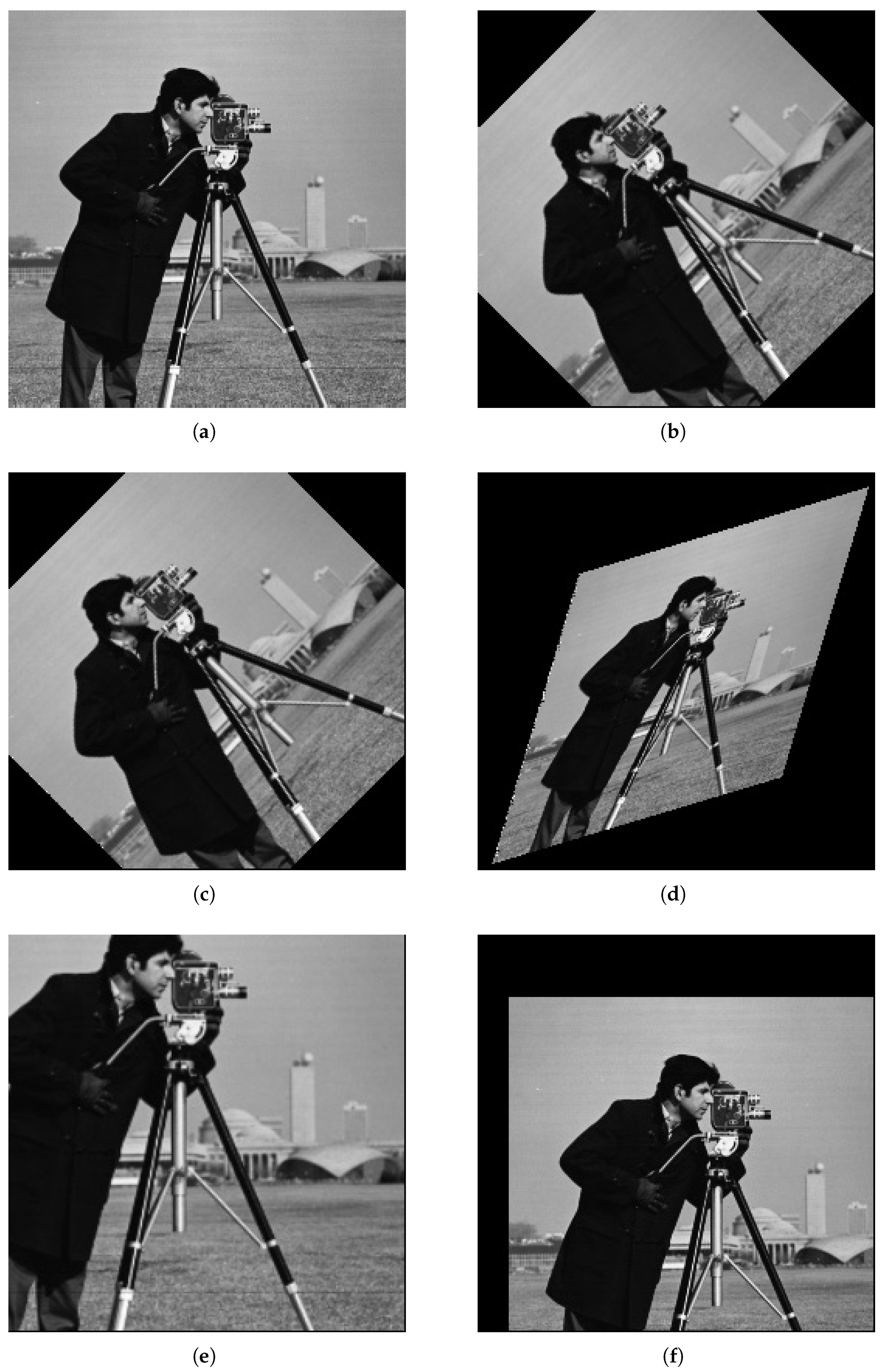

Figure 8a shows the original image, whereas

Figure 8b,c illustrate the affine rotation operations performed using the OpenCV method and the proposed PATRM algorithm, respectively.

Figure 8d–f demonstrate the transformation effects of shearing, scaling, and scaling plus translation. The sample image was a

photographer image. These results indicate that the visual image quality remains unchanged by the proposed PATRM algorithm.

Table 1 quantifies the execution times of the three algorithms. The algorithms used were OpenCV, floating-PATRM, and fixed-PATRM. The evaluation covered different image sizes and hardware platforms. This table enables a quantitative evaluation of the time efficiency of the algorithms at the software level. For a small size

image on the CPU, the fixed-PATRM algorithm achieved an execution time of 2.09 ms. It is 9.5% faster than the floating-PATRM algorithm, with an execution time of 2.31 ms. The speedup is attributed to the reduced computational complexity of fixed-point arithmetic. The fixed-PATRM algorithm is only 10.6% slower than the optimized OpenCV implementation, which has an execution time of 1.89 ms. This gap is negligible. The algorithm features a hardware-oriented design. As the image resolution scales to large formats, two typical examples are

and

. The advantage of fixed-PATRM becomes more pronounced when using a CPU. For the two large sizes, fixed-PATRM outperforms floating-PATRM by 9.4% and 9.3%, respectively. The time cost of fixed-PATRM remains close to that of OpenCV.

When deployed on the PS of the SoC (ARM core), the fixed-PATRM consistently demonstrated a lower latency than the floating-PATRM. For

images, the latency values were 157.68 ms for fixed-PATRM and 173.89 ms for floating-PATRM. These results verified the Q15.16 fixed-point optimization. It effectively mitigates the computational overhead of the affine transformation on embedded processing cores. This higher latency can be attributed to the lower clock frequency of the ARM core and DDR memory access constraints via the AXI interface. Subsequent FPGA-based acceleration in the PL section aims to overcome these limitations. The fixed-PATRM algorithm preserves the image quality, as shown in

Figure 9. In addition, it achieves superior computational efficiency compared with its floating-point counterpart at the software level. This algorithm lays a solid foundation for high-performance hardware implementation on heterogeneous SoC.

4.2. Image Quality Analysis

The image quality of the fixed-point PATRM implementation was evaluated against two benchmarks: the OpenCV affine transformation and floating-point implementation of the PATRM algorithm. The PSNR was computed for rotations ranging from 0° to 90° in 1° increments. PSNR was calculated using equation [

29]:

In Equation (

7), MAX represents the maximum possible pixel value (e.g., 255 for 8-bit grayscale images). The Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the reference image (

) and processed image (

) is given by the following equation:

where M and N denote the height and width of the image in pixels.

and

represent the pixel intensity values at locations

in

and

, respectively.

To evaluate the image quality of our fixed-point hardware implementation, we computed the PSNR and Structural Similarity (SSIM) indices using the OpenCV warpAffine function (double-precision floating-point) and our own floating-point PATRM algorithm implementation software references as the ground truth. The results, labeled as ’OpenCV-Fixed’ and ’Floating-Fixed’ respectively, are plotted against rotation angles in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows that the PSNR value of the proposed algorithm matches well with those of the OpenCV and floating-point PATRM algorithms for BLI. The PSNR value of the proposed algorithm ranged between 26 and 30 dB, remaining stable at approximately 30 dB for angles exceeding 10°. The fixed-point PATRM maintains an average SSIM above 0.980 when compared to the OpenCV benchmark, and above 0.988 compared to the floating-point PATRM implementation across all rotation angles. Even at small angles (0°–10°) where quantization effects are more pronounced, the SSIM remains above 0.98, indicating well-preserved structural fidelity.

At small angles, the PSNR slightly deteriorated. Because the Structural Similarity (SSIM) decreases at small angles, the main reason for the reduction in PSNR is the error in the image structure, rather than a real decline in image quality. Further analysis shows that when the angle approaches 0°, becomes very small. For example, for 1°, the Q15.16 fixed-point representation is . The relative proportion of the quantization error () was (5° is 0.017%), which was significantly larger than that of the error at medium and high angles. This amplifies the deviations in the coordinate calculations and increases the errors in the interpolated pixels, which are relatively high. During the interpolation process from point to point , the fixed-point PATRM introduces quantization errors that differ from the rounding errors inherent in floating-point PATRM. Nevertheless, when compared to the results generated by OpenCV warpAffine function, the images processed by fixed-point PATRM maintain a PSNR above 26 dB, confirming that the introduced errors remain within an acceptable range for industrial imaging applications.

In the context of industrial imaging for tasks such as scanner correction and alignment, a PSNR above 26 dB is widely regarded as acceptable for maintaining functional accuracy [

21,

30,

31]. The proposed fixed-point PATRM consistently exceeds this practical threshold (PSNR > 26 dB, SSIM > 0.98) across all transformations, confirming its suitability for real-time industrial applications where a balance between computational efficiency and image quality is paramount [

32,

33].

4.3. Implementation Results

The hardware platform used in this experiment was an Anlogic DR1M90GEG400 development board. The PL section of the board was equipped with a high-performance FPGA. In this study, an affine transformation accelerator was designed. The operating frequency of the accelerator was 200 MHz. The proposed architecture was implemented directly on the FPGA of the SoC system using Verilog HDL.

Table 2 presents the FPGA resource utilization of the proposed PATRM accelerator. The accelerator was synthesized and implemented on an Anlogic DR1 development board. The results demonstrate the high resource efficiency of the proposed architecture. Specifically, the design consumes only 2934 look-up tables (LUT), which accounts for 5.59% of the 52,480 available resources. This low utilization originates from two key optimizations. The multiplication-free design of the PATRM algorithm and the adoption of pipelined logic, both of which enhance the efficiency of the coordinate transformation and interpolation circuits. Regarding the embedded random access memory (ERAM), 66 units were utilized, representing 23.57% of the 280 available units. These units mainly serve to cache pre-fetched pixel blocks and the intermediate interpolation results. The AXI4 burst transmission mechanism reduces redundant storage requirements. The usage of digital signal processors (DSP) is minimal at 17 units, which constitutes 7.08% of the 240 available DSPs. Multiplications in Equations (

2) and (

3) are eliminated via recurrence relations between neighboring pixels. The 17 DSPs are used primarily for address calculation during the first read operation and interpolation calculations (Equation (

6)). This low DSP consumption is enabled by Q15.16 fixed-point arithmetic. Complex floating-point operations are replaced with streamlined integer computations through this arithmetic. This replacement reduces the demand for dedicated DSP resources.

The proposed PATRM was deployed in an industrial scanner. During the operation of the scanner, slight movements or vibrations of the machine can cause the position of the scanned image to be shifted. To obtain an image in the correct position, centering and rotation operations are required. The PS controls the scanning process and calculation of the transformation matrix and sends the correction commands to the PL through the AXI interface. This achieves image correction at 25 FPS in

format. The scanning and correction results are presented in

Figure 10. The process of converting the original image into a correctly positioned image was completed.

Table 3 compares the performance of the proposed PATRM algorithm with that of traditional affine transformation algorithms. Two key dimensions are involved in this process. They are the processing rate, expressed as pixels per second (pixel/s), and hardware architecture. Most traditional algorithms adopt a single FPGA or CPU architecture, whereas only the Block AT algorithm and the proposed PATRM rely on the SoC architecture. Most traditional single-architecture algorithms suffer from low processing efficiencies. For example, the CORDIC algorithm proposed by Jiang et al. runs on the XC2V1000 FPGA, achieving only 4.45 M pixel/s. The CATM algorithm proposed by Lee et al. operates on a CPU, with a performance of 18.72 M pixel/s. The solution proposed by Hernandez et al. was implemented on a Spartan3E1600 FPGA, achieving 39.32 M pixel/s. All these single-architecture methods often generate non-continuous output image addresses, which increase the bus load and restrict system speed. The Block AT algorithm, while implemented on a modern SoC platform, exhibits relatively high LUT (11,000) and BRAM (1800 Kb) consumption for its achieved performance of 24.32 M pixel/s. However, it did not list the usage amount of DSP. In contrast, the proposed PATRM runs on a DR1M90GEG400 based SoC architecture. It achieves a processing rate of 128.21 M pixel/s, far exceeding both traditional single-architecture algorithms and the Block AT (SoC) algorithm. This superior performance stems from the targeted optimization of the PATRM for the SoC characteristics. The linear algebraic properties of transformation matrices are leveraged by PATRM. Continuous data rows are output by the PATRM. This optimizes data transmission under the AXI interface of the SoC. The computation efficiency under the DDR access mechanism is also improved.

Among all the compared methods, only the MATPR algorithm by Biswal et al. achieves a higher throughput (1129.93 M pixel/s). The implementation of multipliers using slices, as opposed to dedicated DSP blocks, leads to higher slice utilization. This peak performance is attained through a deeply pipelined, parallel architecture that employs direct and fixed-pattern DDR data reading. However, this approach increases hardware resource requirements and demands a memory access pattern that is often optimized for specific image dimensions and transformation parameters. Consequently, adapting to images of different sizes or affine transformations typically necessitates hardware redeployment (re-synthesis), resulting in low operational flexibility.

In contrast, the proposed PATRM, architected for the heterogeneous SoC platform, prioritizes a balance between performance, flexibility, and resource efficiency. The high RAM usage in PATRM is attributed to the preallocated space for accommodating images of varying sizes and the buffer occupancy required for DMA operations. While its throughput (128.21 M pixel/s) is lower than MATPR peak, it sustains real-time performance for target applications. Crucially, PATRM design leverages the spatial locality of affine transformations to prefetch contiguous data via parameterized AXI4 burst transmission. This allows the PS to dynamically calculate and output different affine matrices according to application needs. The PATRM accelerator in the PL can then adapt to these new parameters in real-time without hardware redesign or reconfiguration. This inherent flexibility enables seamless support for diverse affine operations and variable image sizes, outperforming most traditional single FPGA/CPU solutions and the existing SoC-based Block AT algorithm. Thus, this study demonstrates that PATRM provides an effective, superior, and highly adaptable solution for practical industrial imaging scenarios where both performance and adaptability are required.

4.4. Latency and Scalability Analysis

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the operational characteristics of this system, an analysis of latency composition and architectural scalability is presented. The overall latency for processing a image arises from both the PS and the PL. The PS contributes approximately 10% of the total latency, which primarily includes the time for the ARM core to compute the affine transformation matrix and, more significantly, to configure the PL parameters and initiate DMA transfers via the AXI_Lite interface. This control overhead remains relatively constant across different image sizes after initial setup. The dominant portion (90%) stems from the PL, encompassing the complete PATRM computation pipeline: coordinate address generation, burst data prefetching from DDR via AXI_HP, the bilinear interpolation calculation, and the final write-back of results. This distribution validates the efficacy of the heterogeneous architecture, which successfully offloads the computationally intensive, deterministic pixel processing to the parallel PL while retaining flexible control in the PS.

The proposed accelerator architecture is inherently scalable to accommodate more complex imaging requirements. For multi-channel color images such as RGB, the most straightforward extension involves replicating the grayscale processing datapath, comprising the coordinate transformation, prefetch logic and interpolation unit for each color channel. This channel-parallel approach would leverage the same shared control logic and AXI/DMA infrastructure, primarily requiring an adjustment to the data path width and a proportional increase in DDR bandwidth, for which the AXI4 burst mechanism remains equally efficient. To handle image data with higher bit depths such as 10, 12 or 16 bits, the Q15.16 fixed-point arithmetic core can be adapted by extending the integer part of the format (for example, extending to Q17.16) while preserving the fractional precision for interpolation. Such an adjustment would have a minimal impact on LUT utilization but might necessitate wider internal datapaths and could moderately increase DSP usage for the interpolation multiplications. These clear pathways for extension underscore the potential of this design potential to meet the demands of advanced industrial applications involving color or high dynamic range content without necessitating a fundamental architectural redesign.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a PATRM accelerator architecture based on a heterogeneous SoC. By decoupling the control and data paths, employing a multiplication-free design, and utilizing AXI4 burst prefetching, the system achieves real-time affine transformation at 25 FPS for images with a resolution of

, striking a favorable balance between throughput and resource efficiency. The system supports real-time affine transformation of images with varying dimensions through dynamic parameter configuration. This capability for real-time processing of images of variable sizes highlights the versatility and computational efficiency of the architecture. This study provides an efficient and reconfigurable hardware solution capable of fulfilling the real-time requirements of affine transformation in image processing applications [

34,

35,

36].

However, this work has several limitations, which point to clear directions for future research. First, the adopted Q15.16 fixed-point arithmetic leads to a noticeable drop in PSNR at very small rotation angles due to the increased relative proportion of quantization error. Second, the performance of the system is heavily relies on contiguous burst data transmission via the AXI4 interface. In practice, if the source image data lacks ideal storage continuity, the efficiency of the prefetching mechanism would be compromised. Furthermore, while the current architecture is primarily validated for grayscale images and possesses a theoretically scalable path for color image processing, its actual throughput and resource consumption under multi-channel data flow require further evaluation.

To address these limitations and further enhance the system, future work will focus on optimizing the AXI4 burst transmission mechanism and on-chip buffer capacity to improve adaptability to diverse data layouts and achieve even faster real-time performance. Advanced interpolation algorithms such as bicubic interpolation will be integrated into the PATRM framework, coupled with targeted hardware optimizations to better balance image quality and computational overhead. Finally, a portable IP core compatible with mainstream SoC/FPGA platforms will be developed to extend the practicality and scalability of this accelerator in broader industrial and consumer electronics applications.