Quantifying the Measurement Precision of a Commercial Ultrasonic Real-Time Location System for Camera Pose Estimation in Indoor Photogrammetry

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Research Objectives

- Develop an automated stationary detection algorithm to support the envisioned walk-around workflow, enabling the system to detect when the operator has paused and signal when measurements meeting precision thresholds have been acquired.

- Evaluate IMU sensor fusion performance across all five proprietary configuration profiles to identify which provides suitable orientation constraints for stationary photogrammetric observations.

- Determine optimal data collection protocols by evaluating both duration (observation windows from 0.25 s to 90 s) and strategy (immediate collection versus threshold-based settling).

- Quantify achievable position and orientation precision under stationary conditions, establishing baseline performance characteristics to inform the weighting of camera pose constraints in photogrammetric bundle adjustment.

1.4. Organization

2. Materials and Methods

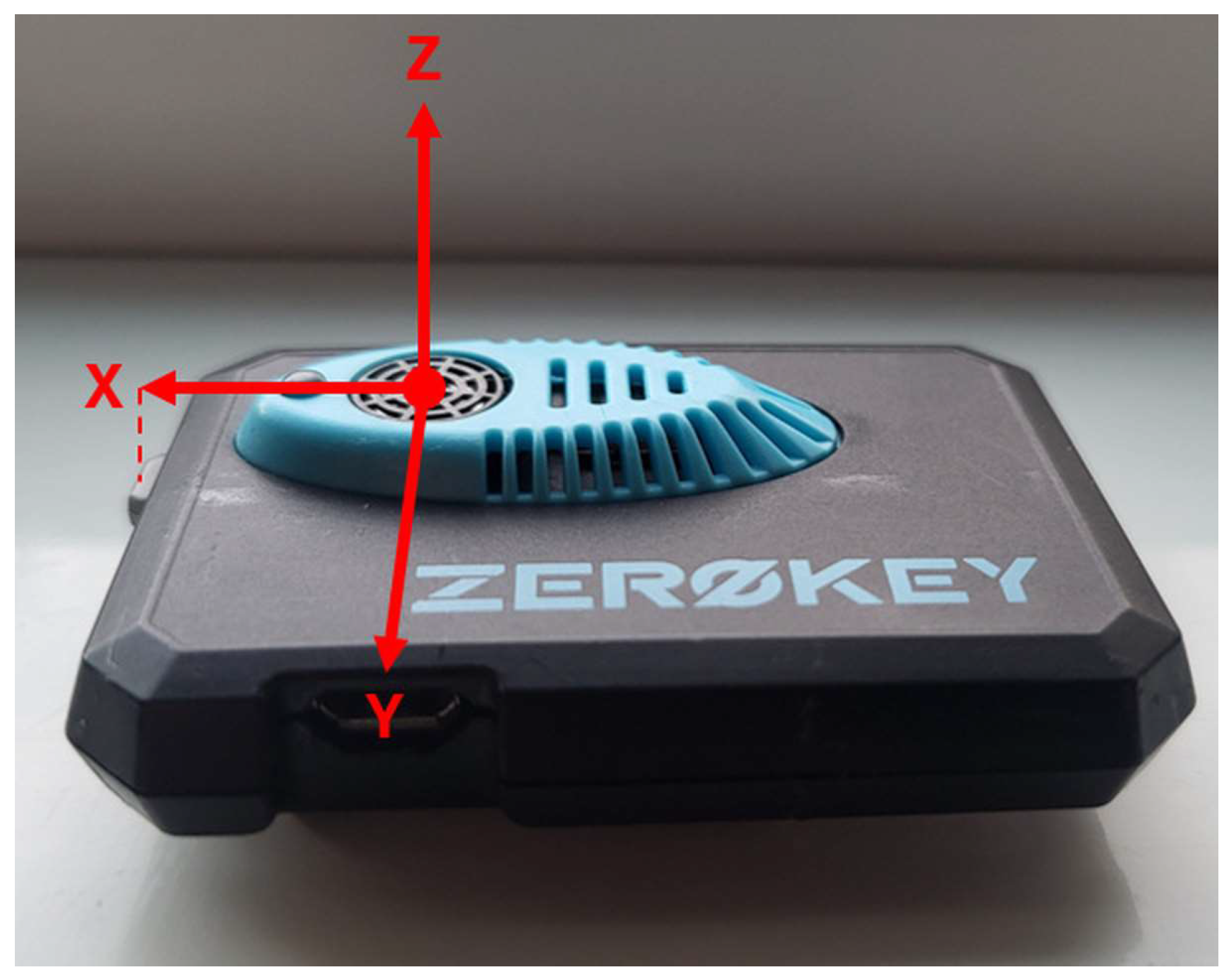

2.1. ZeroKey Quantum RTLS

2.2. Experimental Design and Data Collection

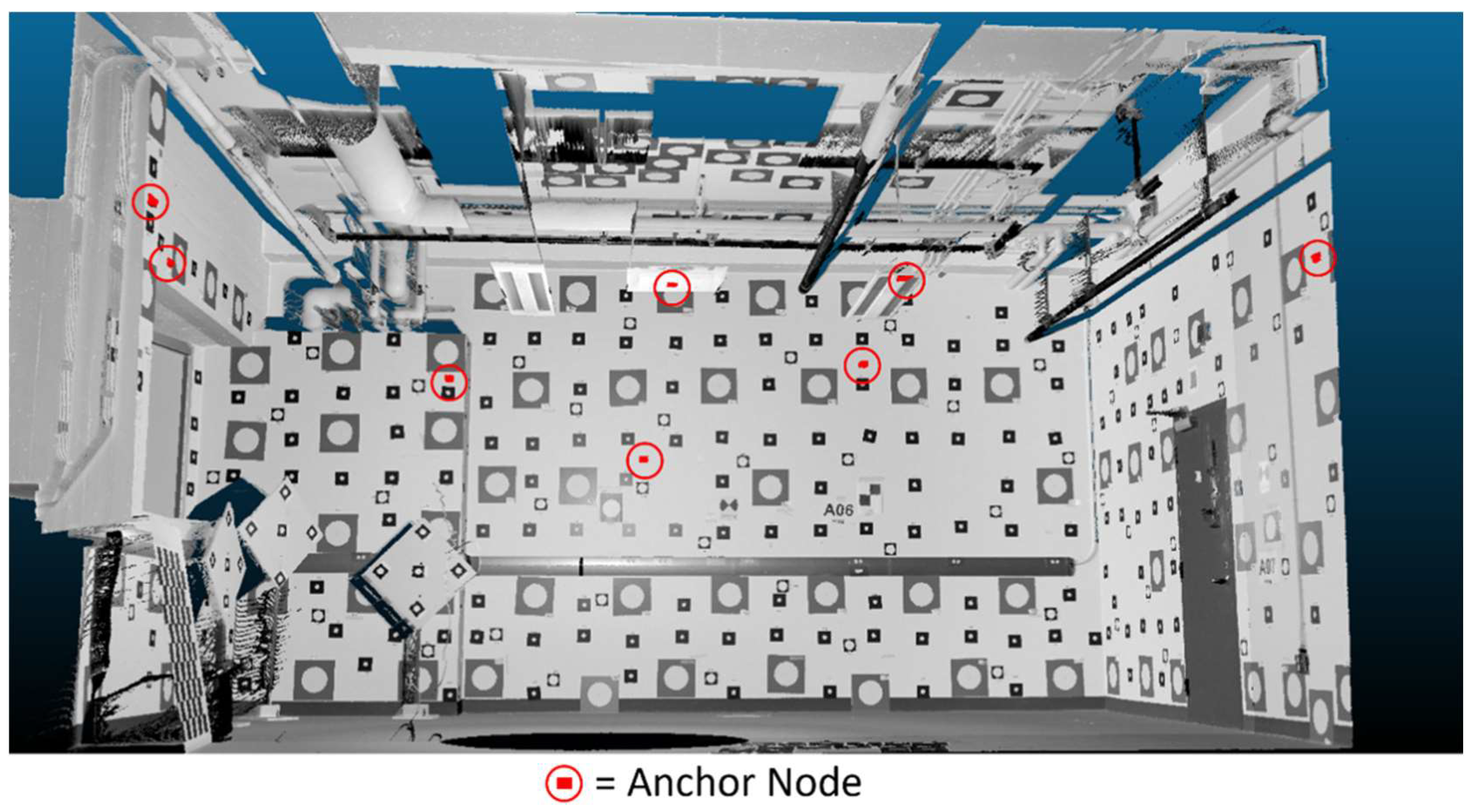

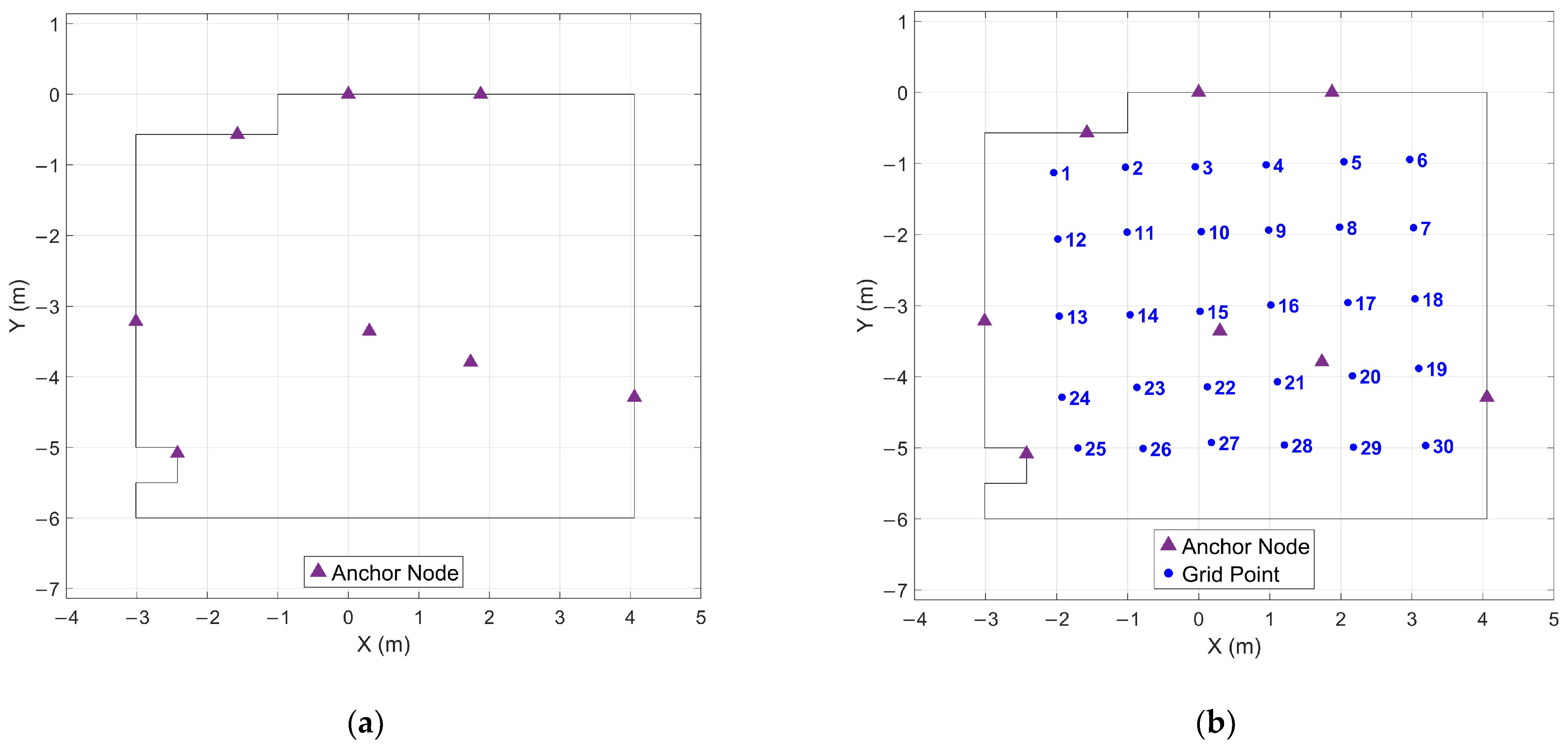

2.2.1. Test Environment and Infrastructure

- Ensuring at least four anchors maintain line-of-sight to any position within the tracked volume to enable robust positioning.

- Maximizing geometric diversity through varied anchor heights and spatial distribution to strengthen positioning accuracy throughout the test area.

- Maintaining practical installation constraints by mounting anchors on existing walls and ceiling surfaces without specialized infrastructure.

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analytical Framework

2.3.1. Stationary Period Detection

2.3.2. Position and Orientation Estimate Analysis

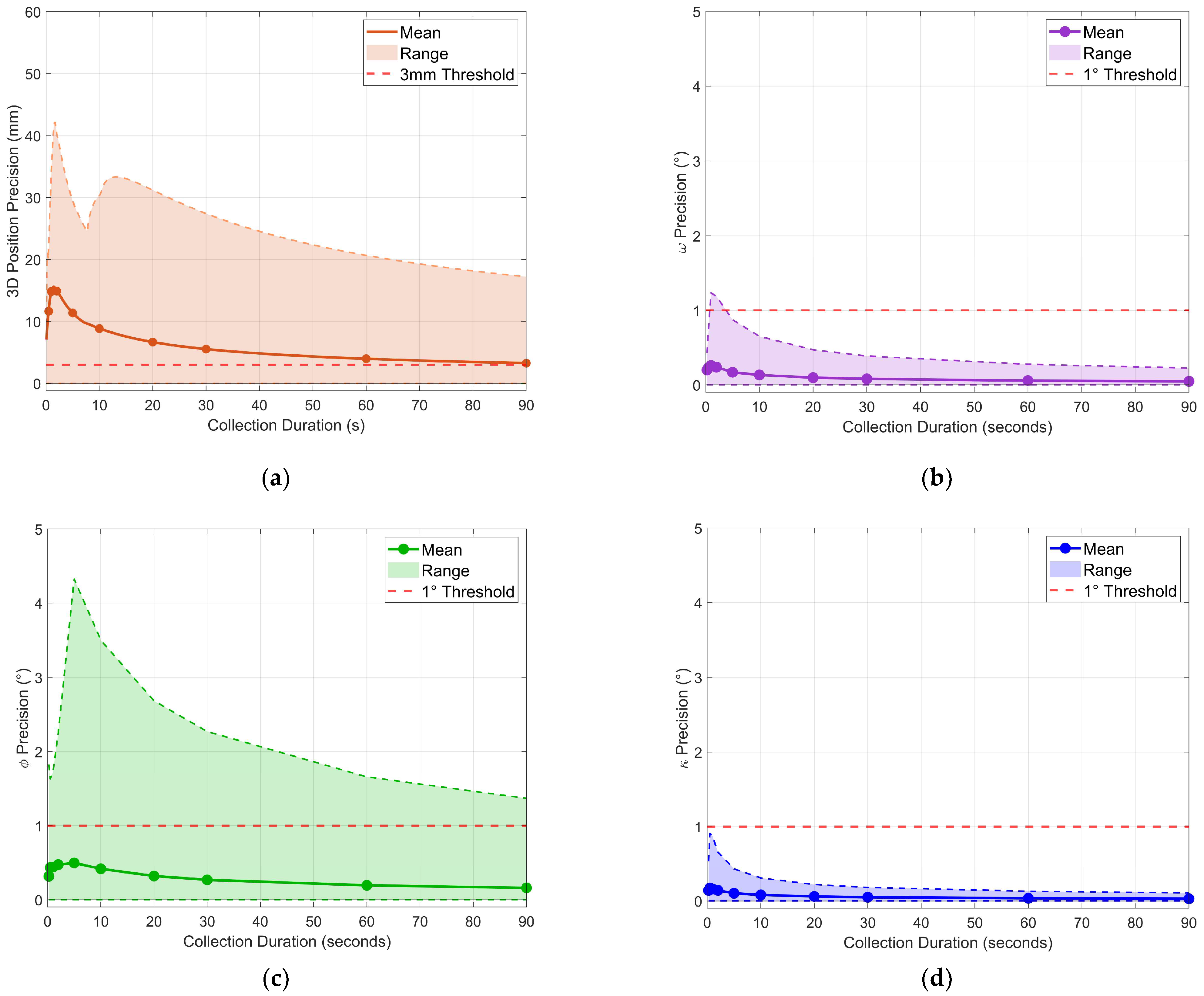

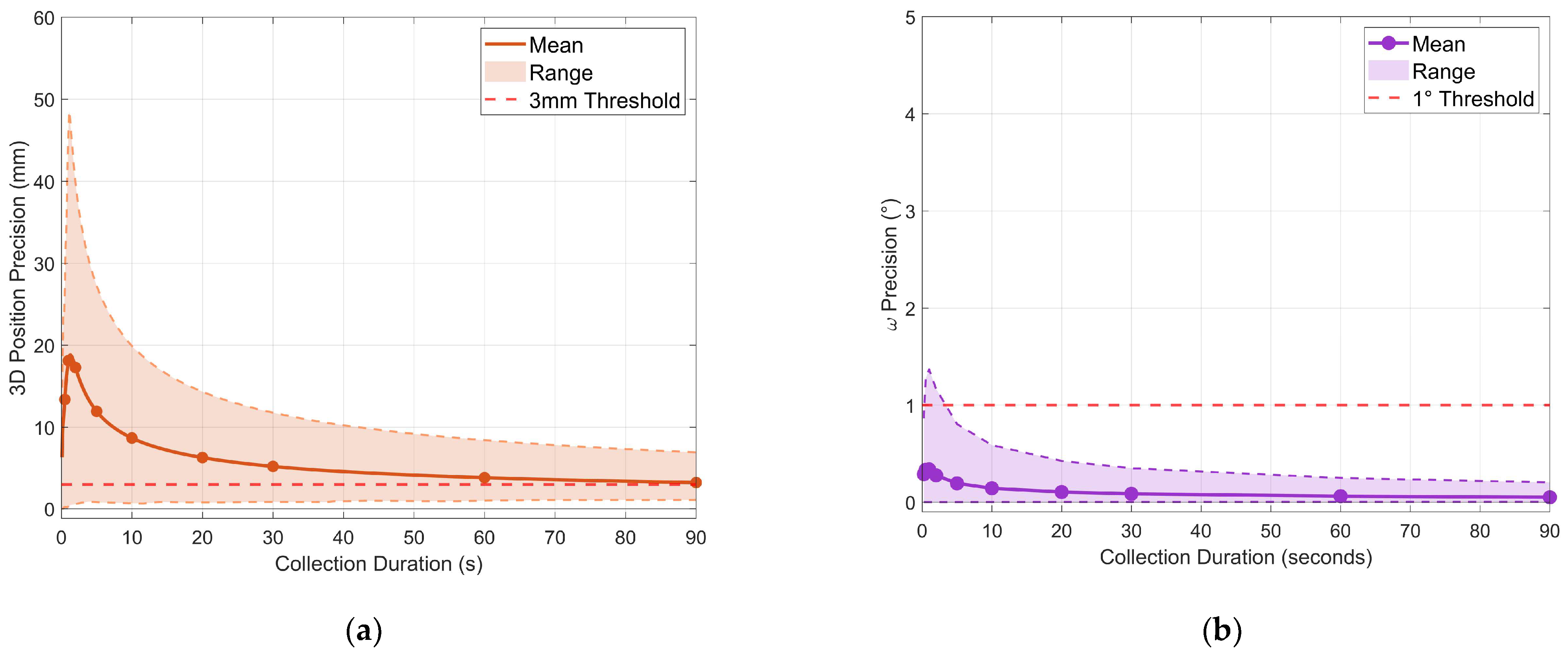

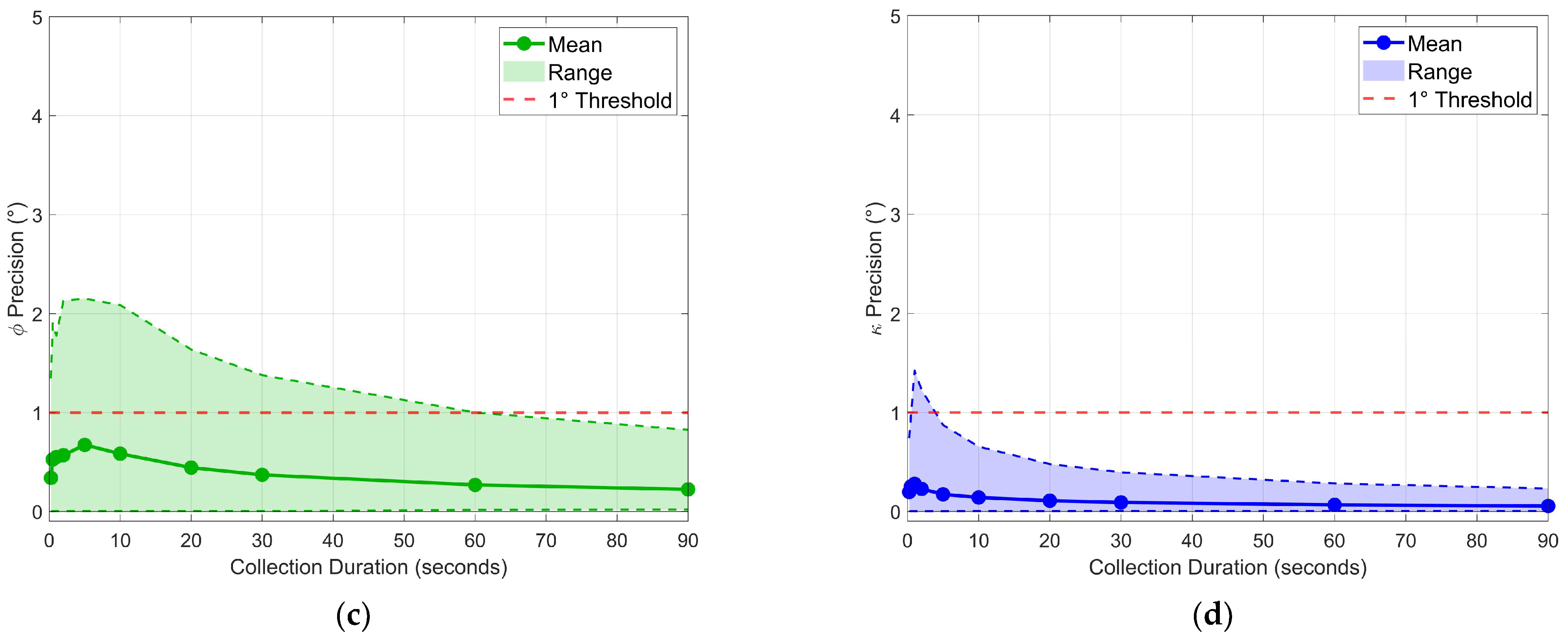

2.3.3. Optimal Duration Analysis

- Success rate: the percentage of grid points where the precision criterion was met.

- Wait time: the delay from the start of the stationary period until the start of the first threshold-meeting window.

- Collection time: wait time plus window duration.

- Final precision: the precision values achieved during the first threshold-meeting window.

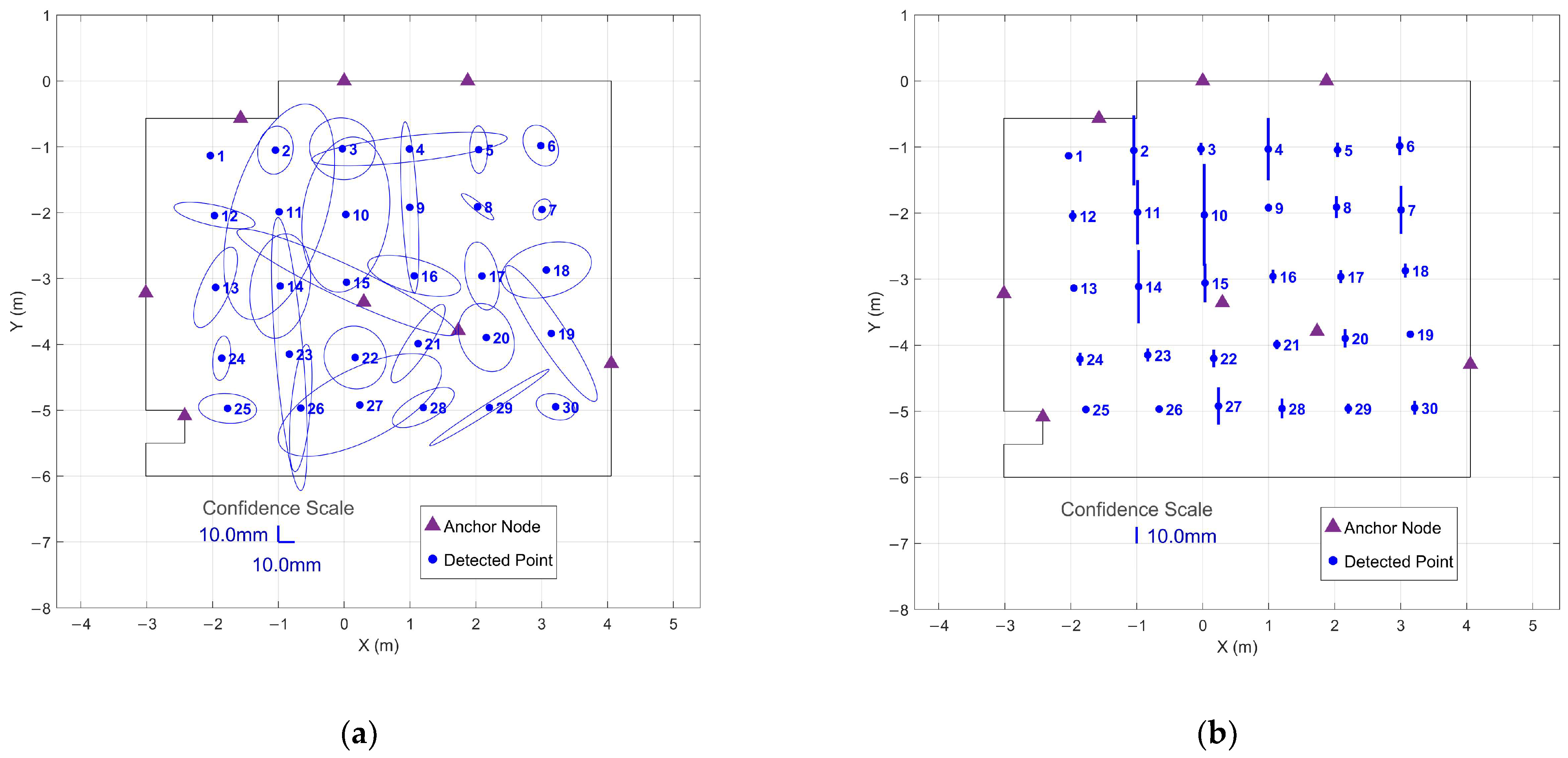

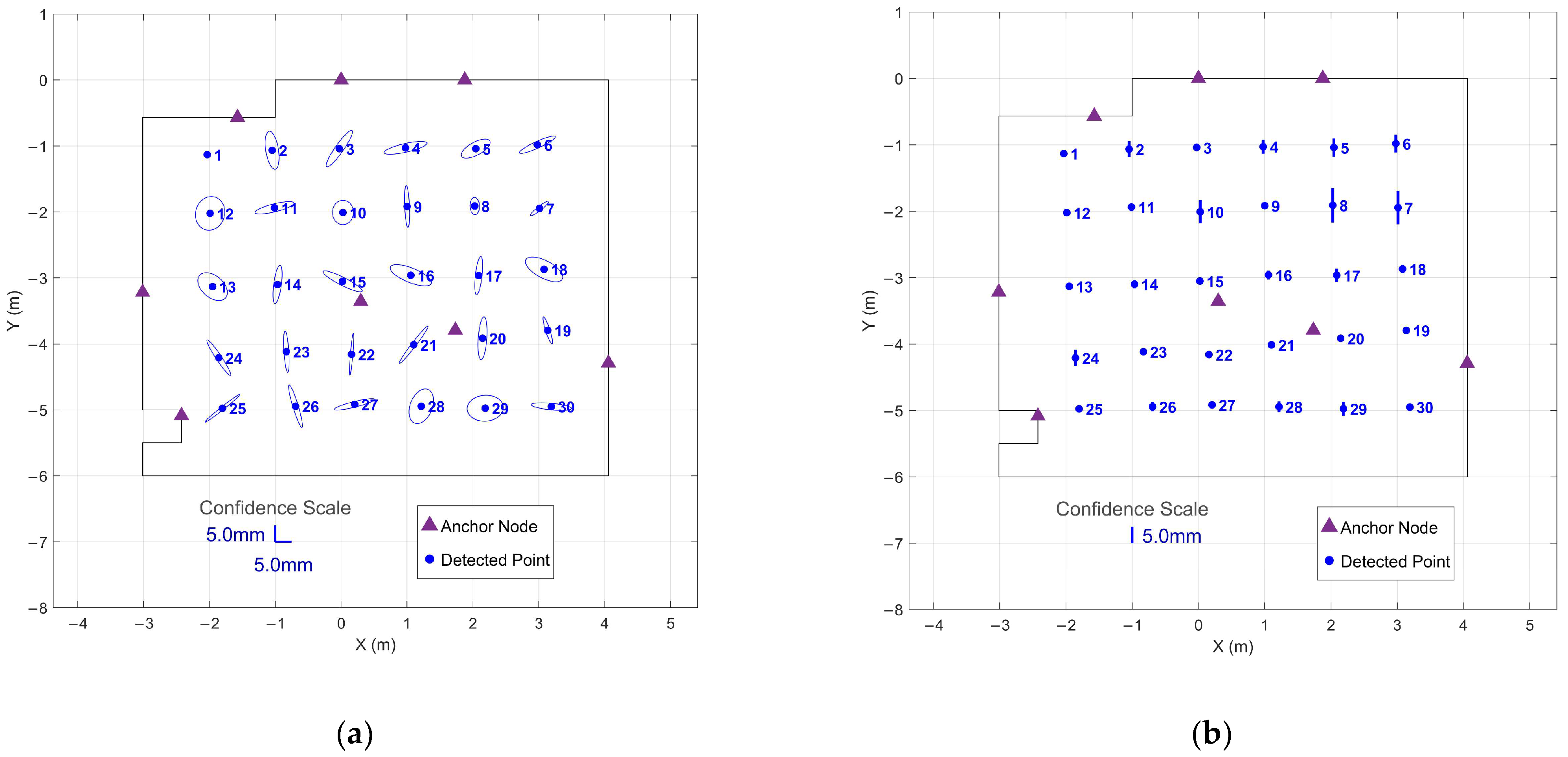

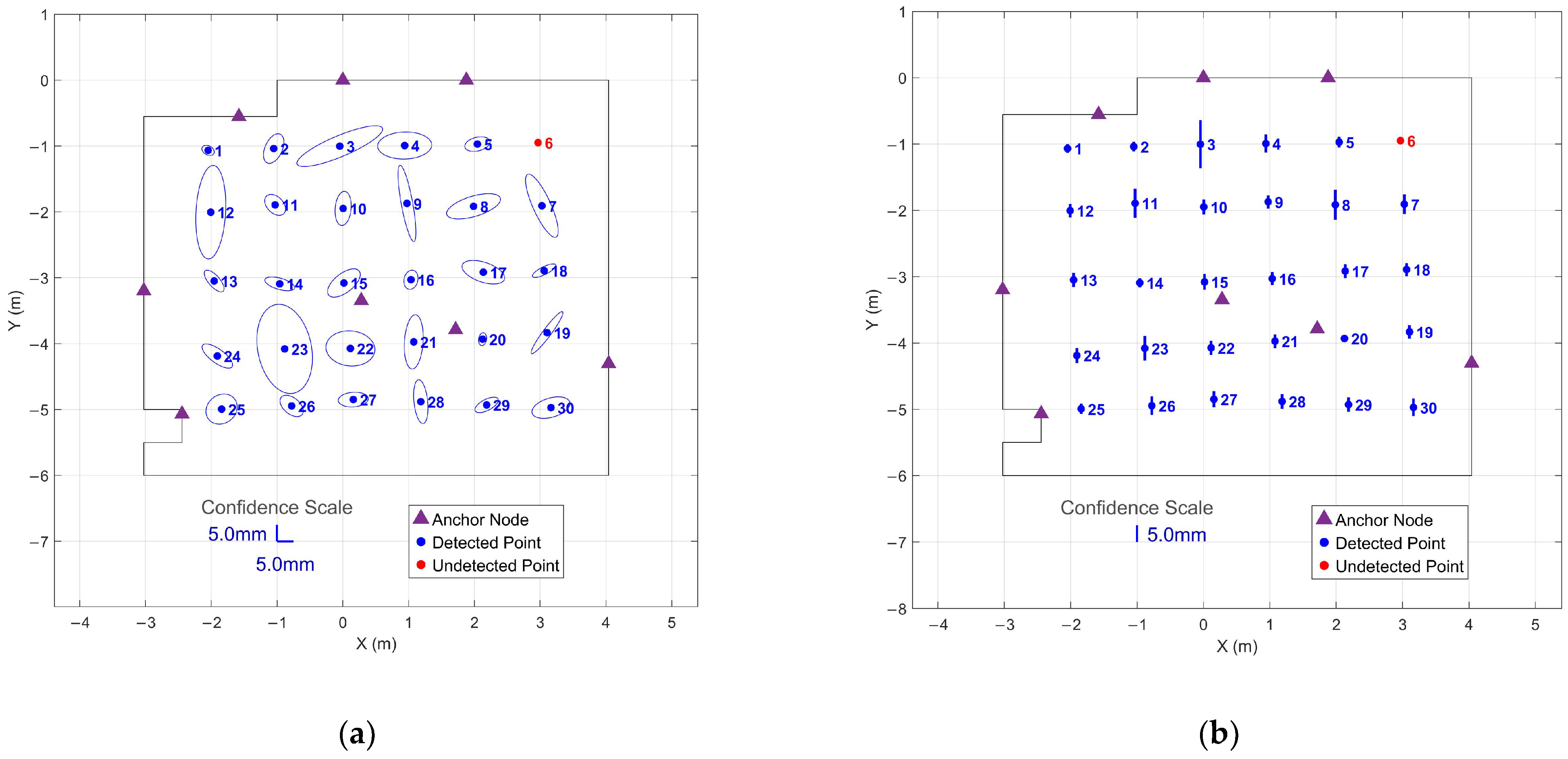

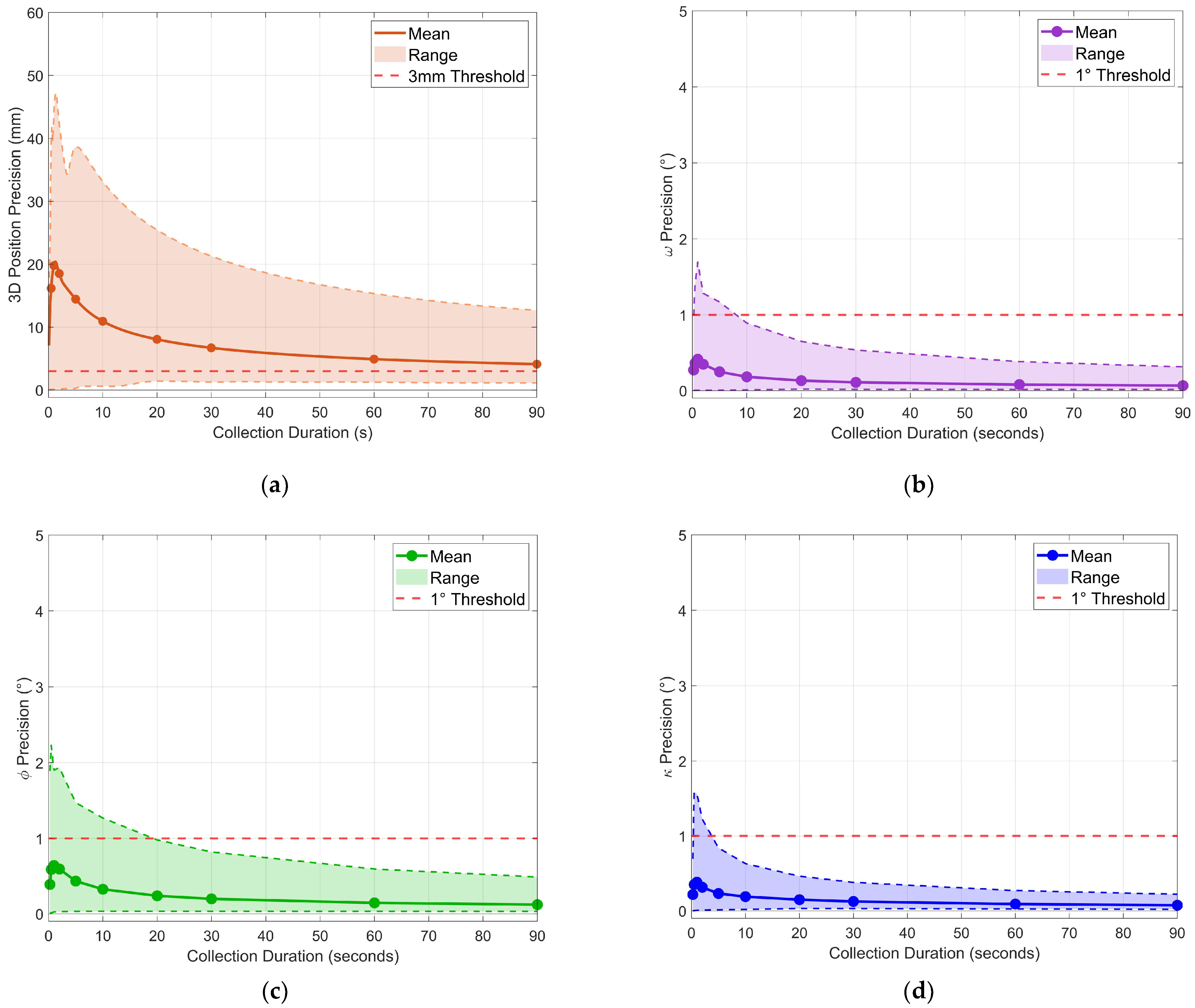

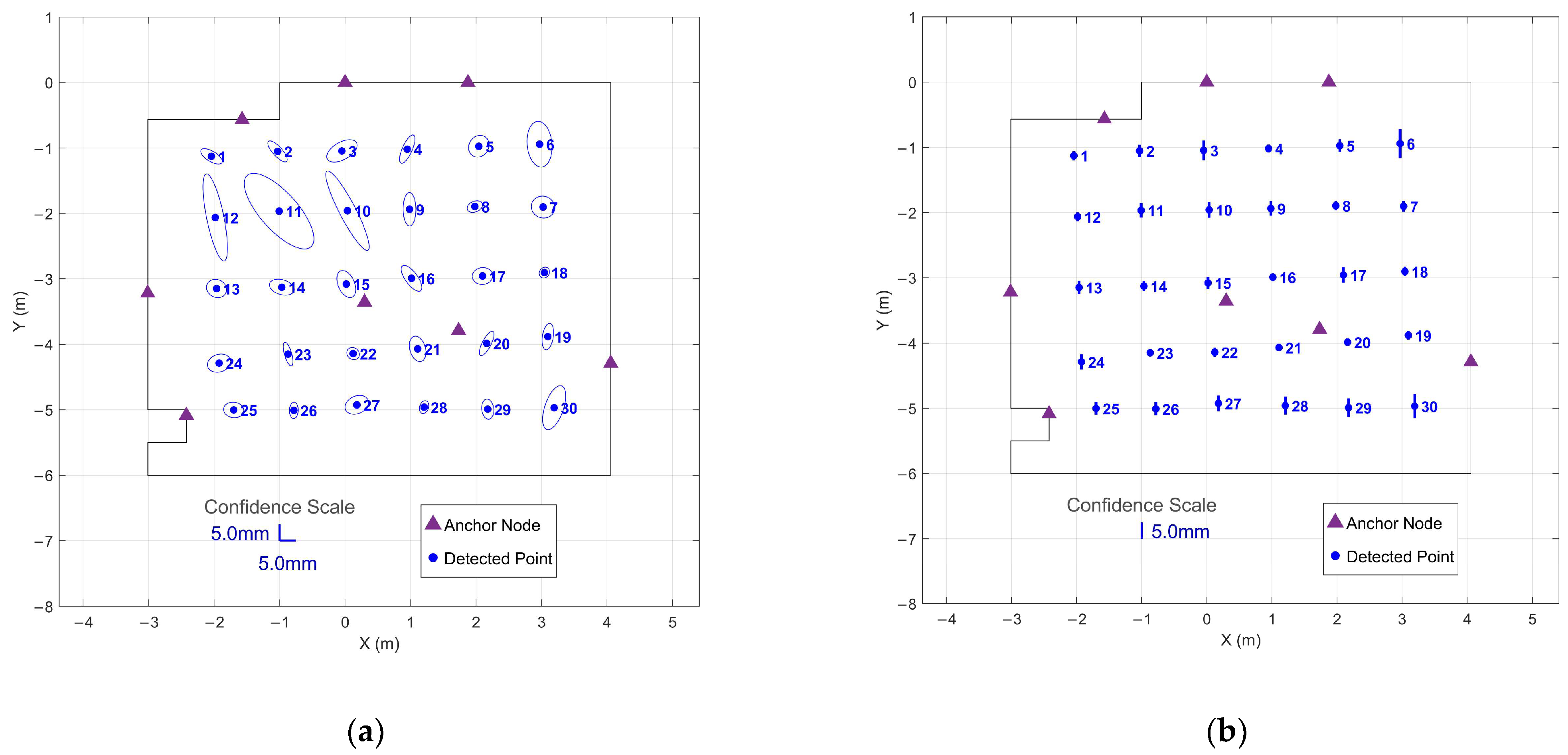

2.3.4. Observation Uncertainty Quantification

3. Results

3.1. Stationary Period Detection

3.1.1. Threshold Determination

3.1.2. Detection Performance

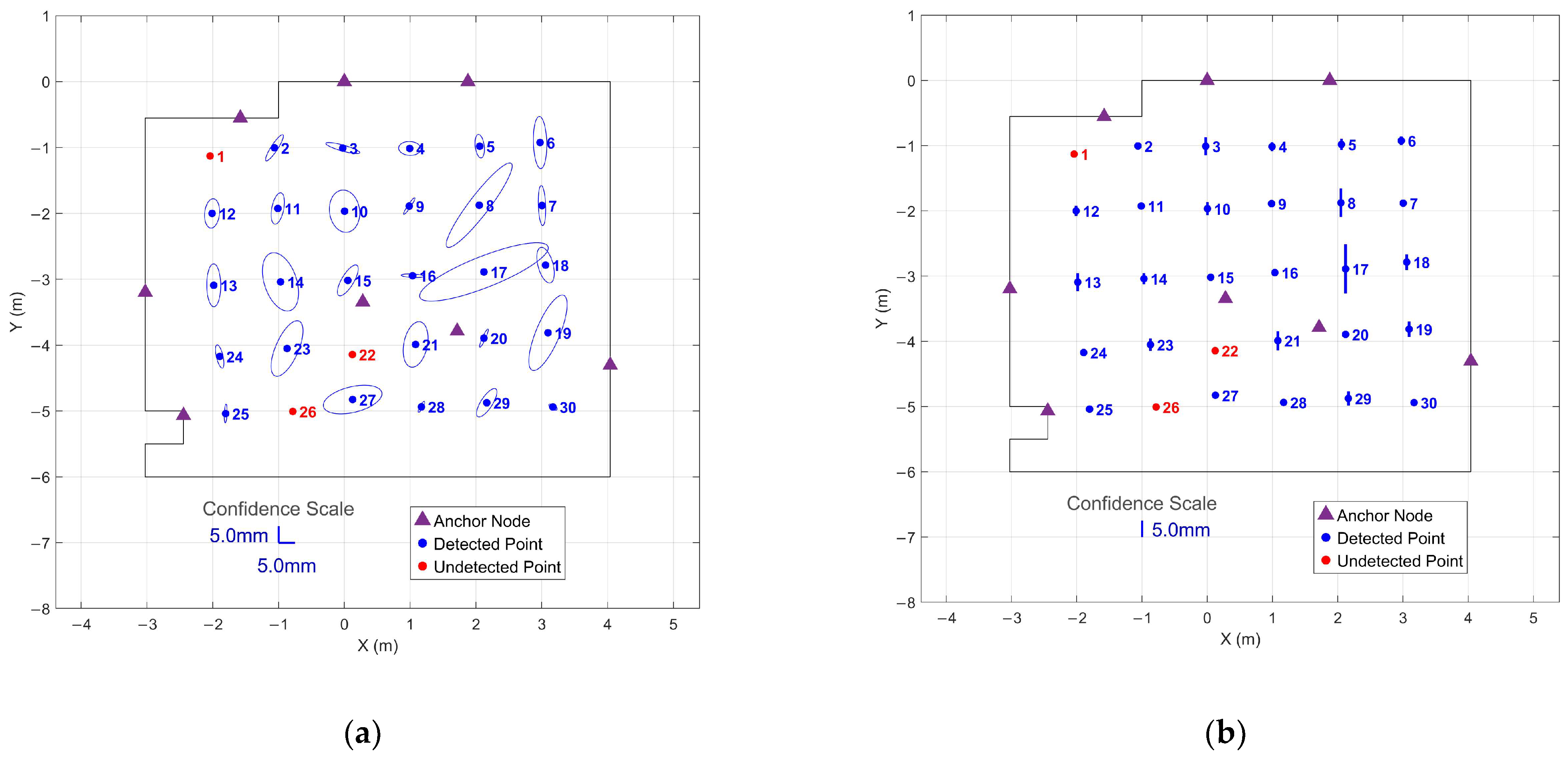

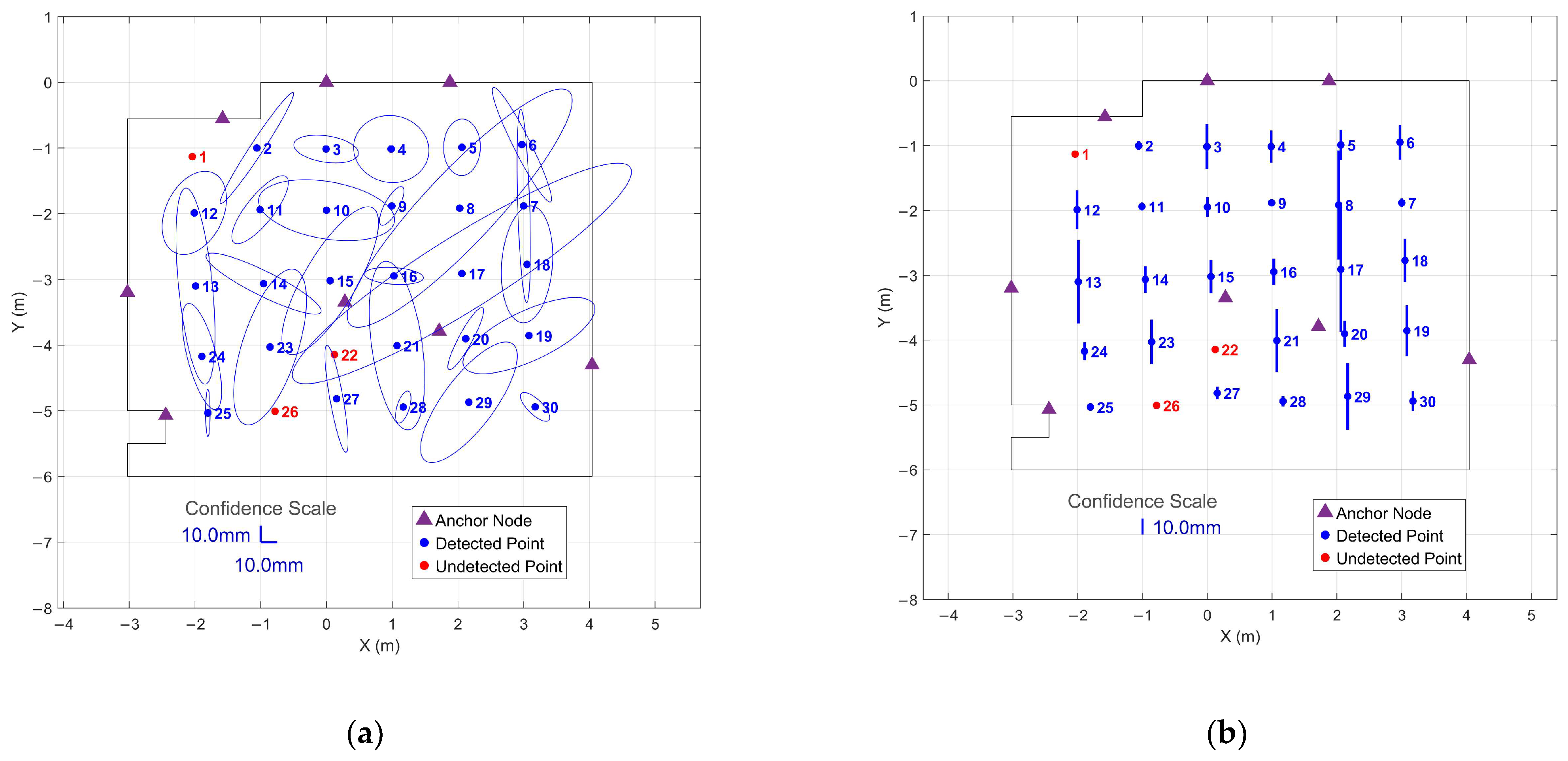

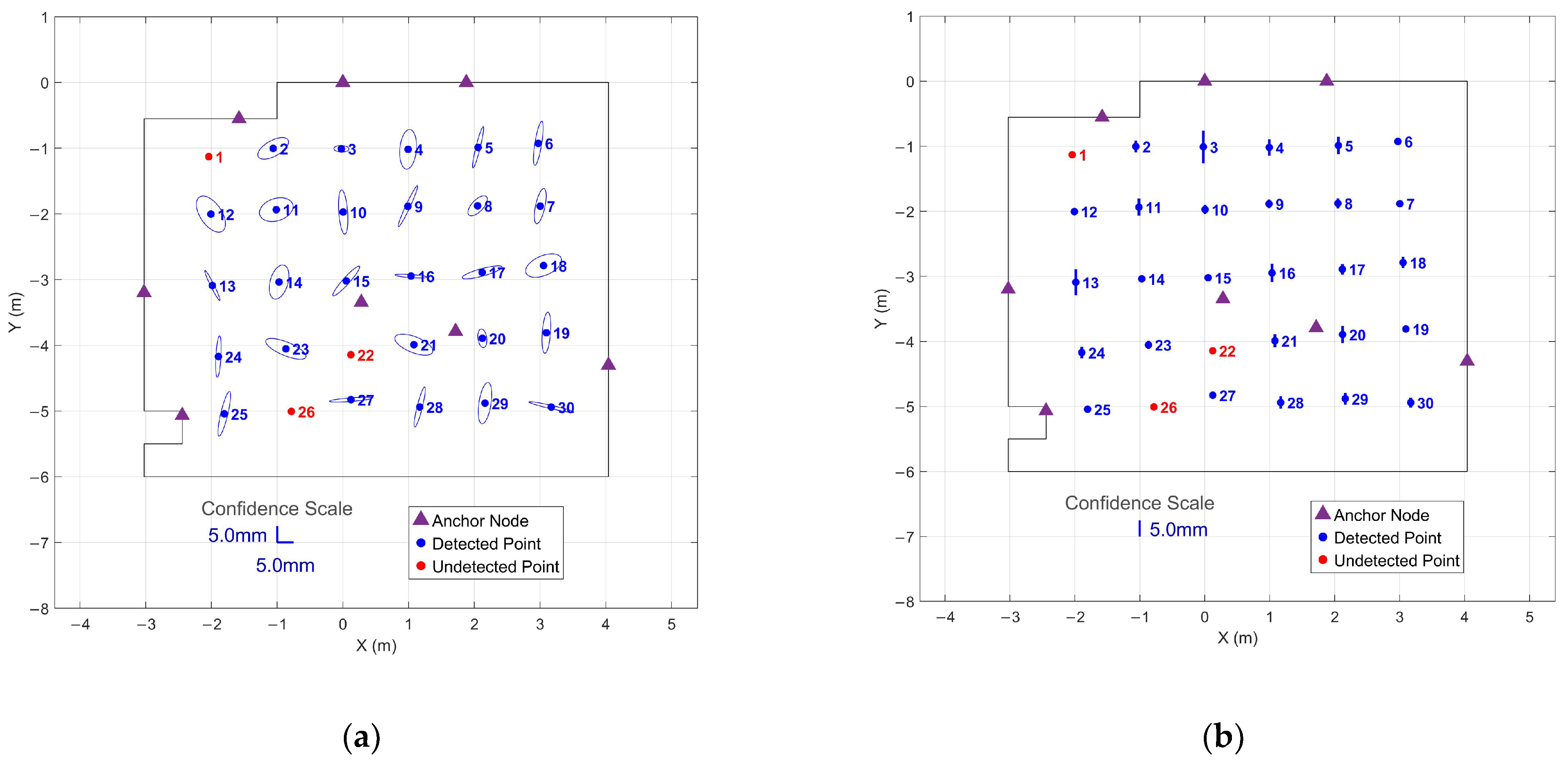

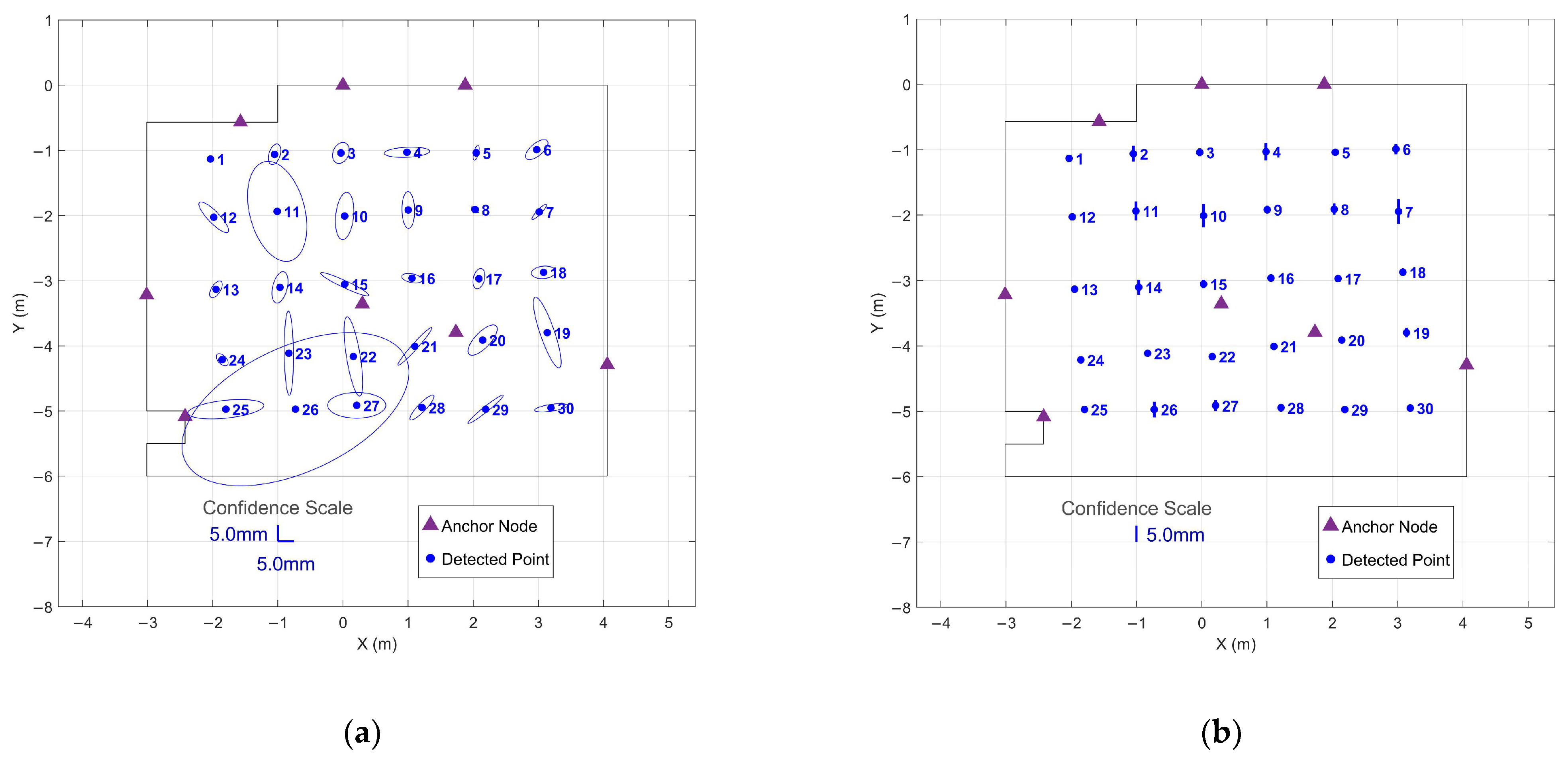

3.2. Position and Orientation Estimate Analysis

3.3. Optimal Duration Analysis

3.3.1. First-Window Analysis

3.3.2. Sliding-Window Threshold Analysis

3.3.3. Optimal Duration Recommendation

3.4. Observation Uncertainty Quantification

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| GCP | ground control point |

| GNSS | global navigation satellite system |

| IMU | inertial measurement unit |

| IPS | indoor positioning system |

| ISO | integrated sensor orientation |

| RMS | root mean square |

| RTLS | real-time location system |

| ToF | time-of-flight |

| UAV | unmanned aerial vehicle |

| UWB | ultra-wideband |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. IMU Profile 1 Results

| Angle | Spatial Mean (°) | Minimum (°) | Maximum (°) | Temporal Precision (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92.0 ± 0.3 | 91.3 | 92.4 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | |

| −5.1 ± 4.3 | −11.9 | 6.1 | 0.16 ± 0.15 | |

| −0.2 ± 0.5 | −0.9 | 1.0 | 0.05 ± 0.07 |

| Time (s) | Initial Precision (mm) | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) | Final Precision (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 11.2 | 100% | 0.65 | 2.25 | 0.90 | 2.50 | 2.4 |

| 0.50 | 15.7 | 100% | 0.90 | 2.25 | 1.40 | 2.75 | 2.5 |

| 1 | 17.7 | 100% | 1.15 | 2.45 | 2.15 | 3.45 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 16.4 | 100% | 1.10 | 2.35 | 3.10 | 4.35 | 2.8 |

| 3 | 14.4 | 100% | 1.00 | 2.30 | 4.00 | 5.30 | 2.8 |

| 5 | 11.7 | 100% | 0.90 | 2.05 | 5.90 | 7.05 | 2.8 |

| 10 | 8.6 | 100% | 0.75 | 1.95 | 10.75 | 11.95 | 2.8 |

| 20 | 6.1 | 100% | 0.55 | 1.85 | 20.55 | 21.85 | 2.8 |

| 30 | 5.0 | 100% | 0.30 | 1.65 | 30.30 | 31.65 | 2.7 |

| 45 | 4.1 | 100% | 0.00 | 1.25 | 45.00 | 46.25 | 2.6 |

| 60 | 3.6 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.70 | 60.00 | 60.70 | 2.5 |

| Time | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.95 | ||

| 1 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 1.40 | ||

| 2 | 1.85 | 2.00 | 3.85 | ||

| 3 | 1.80 | 3.00 | 4.80 | ||

| 5 | 1.75 | 5.00 | 6.75 | ||

| 10 | 1.60 | 10.00 | 11.60 | ||

| 20 | 1.30 | 20.00 | 21.30 | ||

| 30 | 1.00 | 30.00 | 31.00 | ||

| 45 | 0.60 | 45.00 | 45.60 | ||

| 60 | 0.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| Position (mm) | ||||

| Axis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| X | 0.3 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Y | 0.2 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Z | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Orientation (°) | ||||

| Angle | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

Appendix A.2. IMU Profile 3 Results

| Angle | Spatial Mean (°) | Minimum (°) | Maximum (°) | Temporal Precision (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90.8 ± 0.6 | 89.8 | 91.7 | 0.04 ± 0.07 | |

| −4.7 ± 6.9 | −16.9 | 13.9 | 0.16 ± 0.23 | |

| −0.1 ± 0.5 | −1.2 | 1.0 | 0.02 ± 0.04 |

| Time (s) | Initial Precision (mm) | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) | Final Precision (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 9.6 | 100% | 0.47 | 1.80 | 0.72 | 2.05 | 2.4 |

| 0.50 | 11.7 | 100% | 0.75 | 2.40 | 1.25 | 2.90 | 2.6 |

| 1 | 14.8 | 100% | 1.02 | 3.40 | 2.02 | 4.40 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 14.9 | 100% | 1.05 | 3.40 | 3.05 | 5.40 | 2.6 |

| 3 | 13.7 | 100% | 1.02 | 3.40 | 4.02 | 6.40 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 11.4 | 100% | 0.97 | 10.65 | 5.97 | 15.65 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 8.9 | 100% | 0.80 | 10.45 | 10.80 | 20.45 | 2.7 |

| 20 | 6.7 | 100% | 0.53 | 9.95 | 20.53 | 29.95 | 2.7 |

| 30 | 5.5 | 100% | 0.35 | 9.85 | 30.35 | 39.85 | 2.6 |

| 45 | 4.6 | 100% | 0.20 | 9.75 | 45.20 | 54.75 | 2.5 |

| 60 | 4.0 | 100% | 0.05 | 9.65 | 60.05 | 69.65 | 2.5 |

| Time | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.80 | ||

| 1 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1.30 | ||

| 2 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | ||

| 3 | 2.60 | 3.00 | 5.60 | ||

| 5 | 6.30 | 5.00 | 11.30 | ||

| 10 | 6.15 | 10.00 | 16.15 | ||

| 20 | 5.95 | 20.00 | 25.95 | ||

| 30 | 5.75 | 30.00 | 35.75 | ||

| 45 | 5.40 | 45.00 | 50.40 | ||

| 60 | 5.05 | 60.00 | 65.05 |

| Position (mm) | ||||

| Axis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| X | 0.0 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Y | 0.0 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Z | 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Orientation (°) | ||||

| Angle | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

Appendix A.3. IMU Profile 4 Results

| Angle | Spatial Mean (°) | Minimum (°) | Maximum (°) | Temporal Precision (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90.8 ± 0.9 | 88.8 | 92.1 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | |

| −6.5 ± 5.0 | −14.2 | 2.5 | 0.23 ± 0.16 | |

| −0.6 ± 0.6 | −1.5 | 0.3 | 0.04 ± 0.06 |

| Time (s) | Initial Precision (mm) | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) | Final Precision (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 10.9 | 100% | 0.55 | 1.60 | 0.80 | 1.85 | 2.4 |

| 0.50 | 13.4 | 100% | 1.00 | 2.70 | 1.50 | 3.20 | 2.5 |

| 1 | 18.1 | 100% | 1.15 | 2.70 | 2.15 | 3.70 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 17.3 | 100% | 1.15 | 2.65 | 3.15 | 4.65 | 2.7 |

| 3 | 4.9 | 100% | 1.10 | 2.60 | 4.10 | 5.60 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 12.0 | 100% | 1.10 | 2.40 | 6.10 | 7.40 | 2.8 |

| 10 | 8.7 | 100% | 1.00 | 2.00 | 11.00 | 12.00 | 2.7 |

| 20 | 6.3 | 100% | 0.75 | 1.90 | 20.75 | 21.90 | 2.7 |

| 30 | 5.2 | 100% | 0.50 | 1.75 | 30.50 | 31.75 | 2.8 |

| 45 | 4.4 | 100% | 0.35 | 1.45 | 45.35 | 46.45 | 2.7 |

| 60 | 3.8 | 100% | 0.20 | 1.25 | 60.20 | 61.25 | 2.7 |

| Time | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 1.25 | ||

| 1 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.75 | ||

| 2 | 1.35 | 2.00 | 3.35 | ||

| 3 | 1.30 | 3.00 | 4.30 | ||

| 5 | 1.70 | 5.00 | 6.70 | ||

| 10 | 1.40 | 10.00 | 10.40 | ||

| 20 | 0.75 | 20.00 | 20.75 | ||

| 30 | 0.55 | 30.00 | 30.55 | ||

| 45 | 0.20 | 45.00 | 45.20 | ||

| 60 | 0.05 | 60.00 | 60.05 |

| Position (mm) | ||||

| Axis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| X | 0.1 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Y | 0.2 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Z | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Orientation (°) | ||||

| Angle | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.13 | |

| 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

Appendix A.4. IMU Profile 5 Results

| Angle | Spatial Mean (°) | Minimum (°) | Maximum (°) | Temporal Precision (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90.2 ± 0.7 | 88.4 | 91.4 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | |

| −6.6 ± 5.3 | −19.5 | 3.5 | 0.12 ± 0.11 | |

| 0.1 ± 0.7 | −0.7 | 2.1 | 0.06 ± 0.06 |

| Time (s) | Initial Precision (mm) | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) | Final Precision (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 12.2 | 100% | 0.78 | 1.90 | 1.03 | 2.15 | 2.4 |

| 0.50 | 16.2 | 100% | 1.05 | 2.65 | 1.55 | 3.15 | 2.4 |

| 1 | 19.8 | 100% | 1.15 | 2.60 | 2.15 | 3.60 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 18.5 | 100% | 1.12 | 3.70 | 3.12 | 5.70 | 2.7 |

| 3 | 16.6 | 100% | 1.10 | 3.70 | 4.10 | 6.70 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 14.5 | 100% | 1.08 | 3.65 | 6.08 | 8.65 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 10.9 | 100% | 0.95 | 3.55 | 10.95 | 13.55 | 2.8 |

| 20 | 8.1 | 100% | 0.75 | 3.40 | 20.75 | 23.40 | 2.8 |

| 30 | 6.7 | 100% | 0.57 | 3.35 | 30.57 | 33.35 | 2.8 |

| 45 | 5.6 | 100% | 0.42 | 3.30 | 45.42 | 48.30 | 2.7 |

| 60 | 4.9 | 100% | 0.10 | 3.10 | 60.10 | 63.10 | 2.6 |

| Time | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.45 |

| 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.80 | ||

| 1 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.80 | ||

| 2 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 2.75 | ||

| 3 | 0.70 | 3.00 | 3.70 | ||

| 5 | 2.55 | 5.00 | 7.55 | ||

| 10 | 1.90 | 10.00 | 11.90 | ||

| 20 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 20.00 | ||

| 30 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | ||

| 45 | 0.00 | 45.00 | 45.00 | ||

| 60 | 0.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| Position (mm) | ||||

| Axis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| X | 0.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Y | 0.1 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Z | 0.1 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Orientation (°) | ||||

| Angle | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.09 | |

| 0.02 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.12 | |

| 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

References

- Ackermann, F. Practical Experience with GPS Supported Aerial Triangulation. Photogramm. Rec. 1994, 14, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.R. Aerotriangulation without Ground Control. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1987, 53, 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, K.; Chapman, M.; Cannon, E.; Gong, P. An Integrated INS/GPS Approach to the Georeferencing of Remotely Sensed Data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1993, 59, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, M. Direct Geocoding—Is Aerial Triangulation Obsolete? Herbert Wichmann Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartayeva, Y.; Chan, H.C.B.; Ho, Y.H.; Chong, P.H.J. A Survey of Indoor Positioning Systems Based on a Six-Layer Model. Comput. Netw. 2023, 237, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Darabi, H.; Banerjee, P.; Liu, J. Survey of Wireless Indoor Positioning Techniques and Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 2007, 37, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, A.; Al-Salman, A.; Alsaleh, M.; Alnafessah, A.; Al-Hadhrami, S.; Al-Ammar, M.A.; Al-Khalifa, H.S. Ultra Wideband Indoor Positioning Technologies: Analysis and Recent Advances. Sensors 2016, 16, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Liu, G.-P. A Robust High-Accuracy Ultrasound Indoor Positioning System Based on a Wireless Sensor Network. Sensors 2017, 17, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brena, R.F.; García-Vázquez, J.P.; Galván-Tejada, C.E.; Muñoz-Rodriguez, D.; Vargas-Rosales, C.; Fangmeyer, J., Jr. Evolution of Indoor Positioning Technologies: A Survey. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 2630413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, D.; Lv, C. UWB/Binocular VO Fusion Algorithm Based on Adaptive Kalman Filter. Sensors 2019, 19, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Yu, C.; Xia, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, K.; Chen, W. An Indoor Positioning Method Based on UWB and Visual Fusion. Sensors 2022, 22, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Zhan, J.-R. GNSS-Denied UAV Indoor Navigation with UWB Incorporated Visual Inertial Odometry. Measurement 2023, 206, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Hu, C.; Wang, T.; Lv, K.; Guo, T.; Jiang, J.; Hu, W. Research on a Visual/Ultra-Wideband Tightly Coupled Fusion Localization Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Yu, C.; Jiang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, K.; Chen, W. Indoor Pedestrian Positioning Method Based on Ultra-Wideband with a Graph Convolutional Network and Visual Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Cho, S. Fusion Localization for Indoor Airplane Inspection Using Visual Inertial Odometry and Ultrasonic RTLS. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, Q.; Yang, G.; Liu, P. RFG-TVIU: Robust Factor Graph for Tightly Coupled Vision/IMU/UWB Integration. Front. Neurorobot 2024, 18, 1343644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadruddin, H.; Mahmoud, A.; Atia, M. An Indoor Navigation System Using Stereo Vision, IMU and UWB Sensor Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SENSORS, Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, P.; Schuster, M.J.; Steidle, F. Visual-Inertial SLAM Aided Estimation of Anchor Poses and Sensor Error Model Parameters of UWB Radio Modules. In Proceedings of the 2019 19th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2–6 December 2019; pp. 739–746. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, J.-Y.; Habib, A.F.; Kersting, A.P.; Chiang, K.-W.; Bang, K.-I.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-H. Direct Sensor Orientation of a Land-Based Mobile Mapping System. Sensors 2011, 11, 7243–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, A.P.; Habib, A.; Rau, J. New Method for the Calibration of Multi-Camera Mobile Mapping Systems. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXIX-B1, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Ma, H.; Liu, K.; Luo, W.; Zhang, L. Direct Georeferencing for the Images in an Airborne LiDAR System by Automatic Boresight Misalignments Calibration. Sensors 2020, 20, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, A.; Fissore, F.; Vettore, A. A Low Cost UWB Based Solution for Direct Georeferencing UAV Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulindwa, D.B. Indoor 3D Reconstruction Using Camera, IMU and Ultrasonic Sensors. J. Sens. Technol. 2020, 10, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence Home. Available online: https://zerokey.com/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Leskiw, D.C.; Gao, D.G.; Lowe, M. ZeroKey’s Smart Space Indoor Positioning System [White Paper]; ZeroKey Inc.: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence ZeroKey Info Center. Available online: https://infocentre.zerokey.com/articles/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence Changes in the Mobile Body Frame from Quantum RTLS 1.0 to 2.0. Available online: https://infocentre.zerokey.com/articles/changes-in-the-mobile-body-frame-from-quantum-rtls (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence Anchor Layouts for Starter Kits. Available online: https://infocentre.zerokey.com/articles/anchor-layouts-for-starter-kits (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence Calibrate Your System with the ZeroKey Calibration Wizard. Available online: https://infocentre.zerokey.com/articles/how-to-calibrate-your-positioning-system (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ZeroKey Spatial Intelligence Mobile Training and Mounting Steps. Available online: https://infocentre.zerokey.com/articles/mobile-training-and-mounting-steps (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Markley, F.L.; Cheng, Y.; Crassidis, J.L.; Oshman, Y. Averaging Quaternions. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2007, 30, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, T.; Robson, S.; Kyle, S.; Boehm, J. Close-Range Photogrammetry and 3D Imaging; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-11-030278-3. [Google Scholar]

| IMU Profile | Duration (s) | Number of Points Detected | Detection Rate (%) | Undetected Point IDs | Mean Precision (mm) | Minimum Precision (mm) | Maximum Precision (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 30 | 100% | - | 2.9 | 0.7 | 9.0 |

| 60 | 30 | 100% | - | 2.8 | |||

| 90 | 27 | 90% | 1, 22, 26 | 2.8 | |||

| 2 | 30 | 30 | 100% | - | 2.4 | 1.2 | 5.9 |

| 60 | 30 | 100% | - | 2.4 | |||

| 90 | 30 | 100% | - | 2.4 | |||

| 3 | 30 | 30 | 100% | - | 3.3 | 1.0 | 15.5 |

| 60 | 30 | 100% | - | 3.2 | |||

| 90 | 30 | 100% | - | 3.3 | |||

| 4 | 30 | 30 | 100% | - | 3.3 | 1.5 | 6.3 |

| 60 | 29 | 90% | 6 | 3.2 | |||

| 90 | 29 | 90% | 6 | 3.2 | |||

| 5 | 30 | 30 | 100% | - | 4.1 | 1.1 | 12.1 |

| 60 | 29 | 97% | 6 | 4.0 | |||

| 90 | 28 | 93% | 6, 28 | 4.0 |

| Angle | Spatial Mean (°) | Minimum (°) | Maximum (°) | Temporal Precision (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 89.6 ± 0.6 | 88.1 | 90.6 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | |

| −5.8 ± 8.3 | −22.8 | 10.6 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | |

| −0.4 ± 0.7 | −1.5 | 1.2 | 0.08 ± 0.07 |

| Time (s) | Initial Precision (mm) | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) | Final Precision (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 7.8 | 100% | 0.38 | 1.35 | 0.63 | 1.60 | 2.6 |

| 0.50 | 10.7 | 100% | 0.57 | 1.55 | 1.07 | 2.05 | 2.3 |

| 1 | 11.1 | 100% | 0.60 | 1.50 | 1.60 | 2.50 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 9.7 | 100% | 0.68 | 3.05 | 2.68 | 5.05 | 2.7 |

| 3 | 8.6 | 100% | 0.60 | 3.00 | 3.60 | 6.00 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 7.3 | 100% | 0.55 | 2.95 | 5.55 | 7.95 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 5.5 | 100% | 0.45 | 2.80 | 10.45 | 12.80 | 2.7 |

| 20 | 4.1 | 100% | 0.17 | 13.35 | 20.17 | 33.35 | 2.6 |

| 30 | 3.6 | 100% | 0.03 | 5.45 | 30.03 | 35.45 | 2.6 |

| 45 | 3.1 | 97% | - | ||||

| 60 | 2.8 | 97% | - | ||||

| Time | Success Rate (%) | Median Wait (s) | Maximum Wait (s) | Median Collection Time (s) | Maximum Collection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 100% | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 |

| 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.80 | ||

| 1 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 1.15 | ||

| 2 | 0.15 | 2.00 | 2.15 | ||

| 3 | 0.20 | 3.00 | 3.20 | ||

| 5 | 0.15 | 5.00 | 5.15 | ||

| 10 | 0.05 | 10.00 | 10.05 | ||

| 20 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 20.00 | ||

| 30 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | ||

| 45 | 0.00 | 45.00 | 45.00 | ||

| 60 | 0.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| Position (mm) | ||||

| Axis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| X | 0.1 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Y | 0.1 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Z | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Orientation (°) | ||||

| Angle | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | RMS |

| 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.09 | |

| 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nayko, F.; Lichti, D.D. Quantifying the Measurement Precision of a Commercial Ultrasonic Real-Time Location System for Camera Pose Estimation in Indoor Photogrammetry. Sensors 2026, 26, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010319

Nayko F, Lichti DD. Quantifying the Measurement Precision of a Commercial Ultrasonic Real-Time Location System for Camera Pose Estimation in Indoor Photogrammetry. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010319

Chicago/Turabian StyleNayko, Faith, and Derek D. Lichti. 2026. "Quantifying the Measurement Precision of a Commercial Ultrasonic Real-Time Location System for Camera Pose Estimation in Indoor Photogrammetry" Sensors 26, no. 1: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010319

APA StyleNayko, F., & Lichti, D. D. (2026). Quantifying the Measurement Precision of a Commercial Ultrasonic Real-Time Location System for Camera Pose Estimation in Indoor Photogrammetry. Sensors, 26(1), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010319