User Experience of Virtual Human and Immersive Virtual Reality Role-Playing in Psychological Testing and Assessment: A Case Study of ‘EmpathyVR’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Research Question and Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

- RQ 1: What aspects of IVR role-play and VHs for PTA provide positive and negative experiences for the participants?

- RQ 2: Do the participants’ prior IVR experience affect their sense of embodiment during role-play with VHs in EmpathyVR?

- RQ 3. Does the participants’ immersion level affect their satisfaction with the IVR experience during role-play with VHs in EmpathyVR?

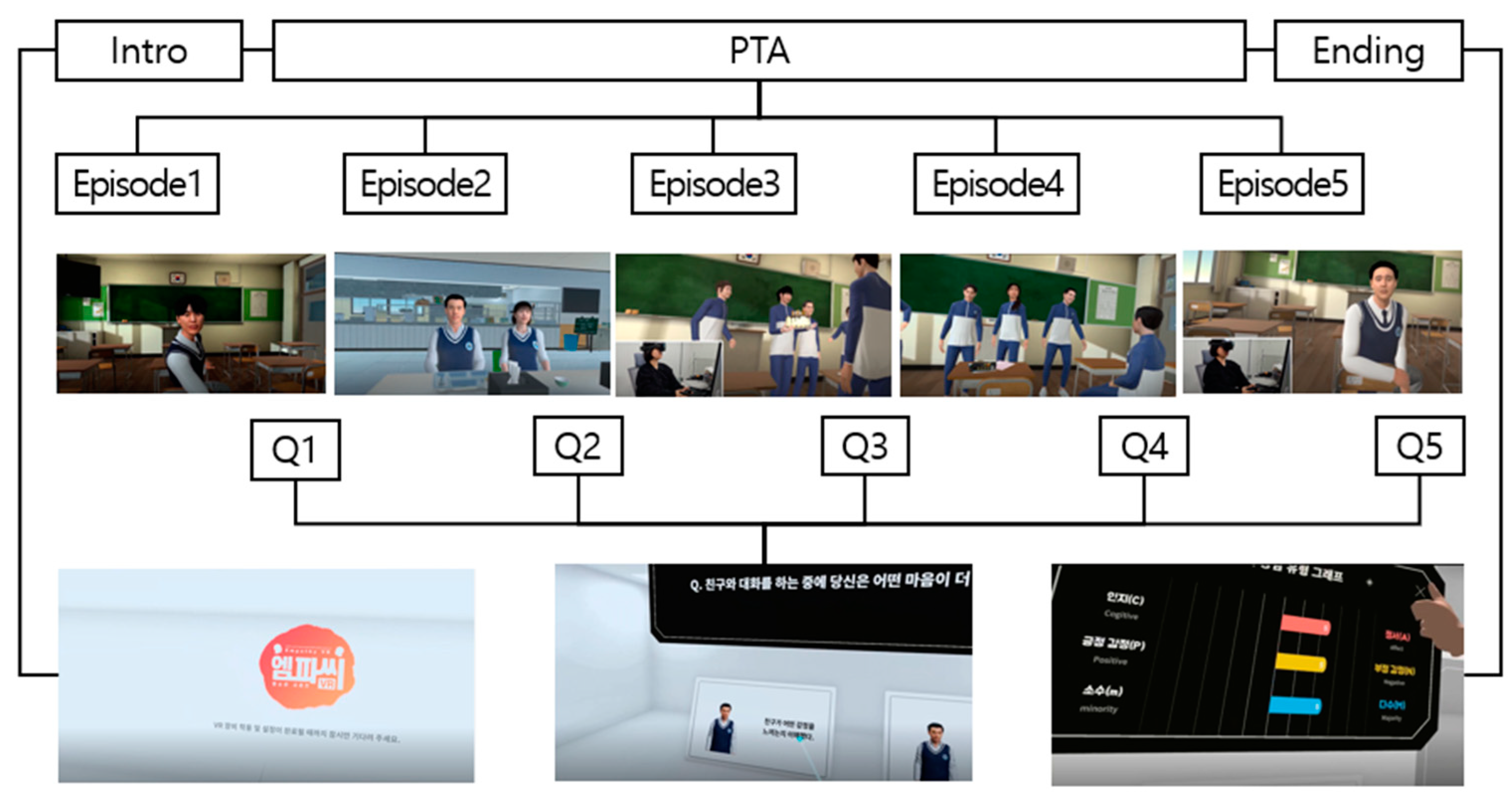

3.2. Stimulus: EmpathyVR

3.3. Experimental Design

3.3.1. Instruments

- Prior experience with IVR (pre-test): The participants were asked to evaluate their prior IVR experience on a four-point Likert scale, with the following responses: never (0), rarely (1), occasionally (2), frequently (3). This was performed to ascertain the extent of the participants’ experience with IVR before the experiment.

- Embodiment (post-test): This section included three questions rated on a seven-point Likert scale to measure participants’ sense of embodiment within a virtual environment [49]. The questions focused on the extent to which the participants felt that their virtual body was their own, their ability to control it as if it were real, and their perception of their body’s existence in the virtual space.

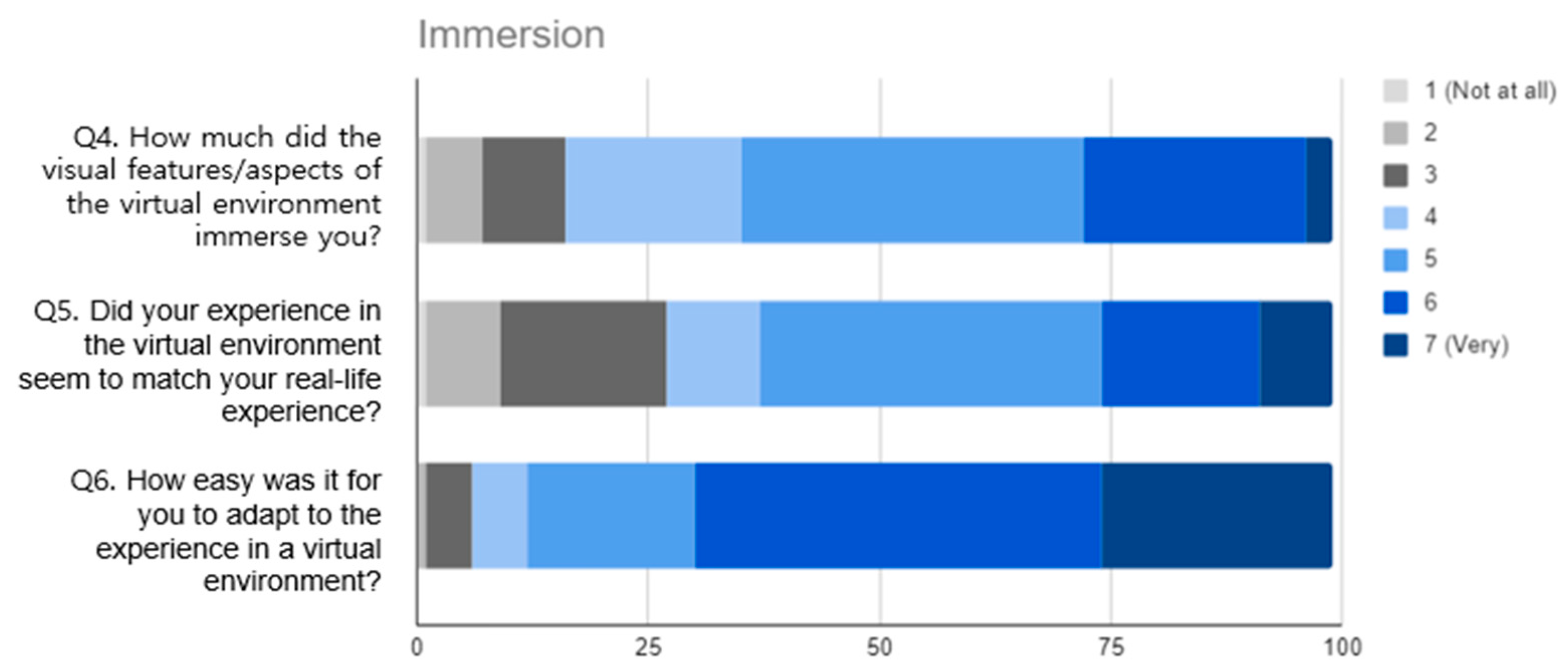

- Immersion (post-test): Three questions assessed the level of immersion on a seven-point Likert scale [50]. These questions evaluated the immersion of the visual aspects of the virtual environment, whether the EmpathyVR experience matched real-life experiences, and how easily the participants adapted to the virtual environment.

- Satisfaction with Empathy Diagnosis Content (post-test): A 10-point question asked participants how likely they were to recommend the IVR content to other middle and high-school students [51] to measure their overall satisfaction with the content. Open-ended questions were used to explore the elements of user satisfaction.

3.3.2. Participants

3.3.3. Procedure

3.3.4. Data Analysis

3.3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Result

4.1. Prior Experience with IVR

4.2. Embodiment and Immersion

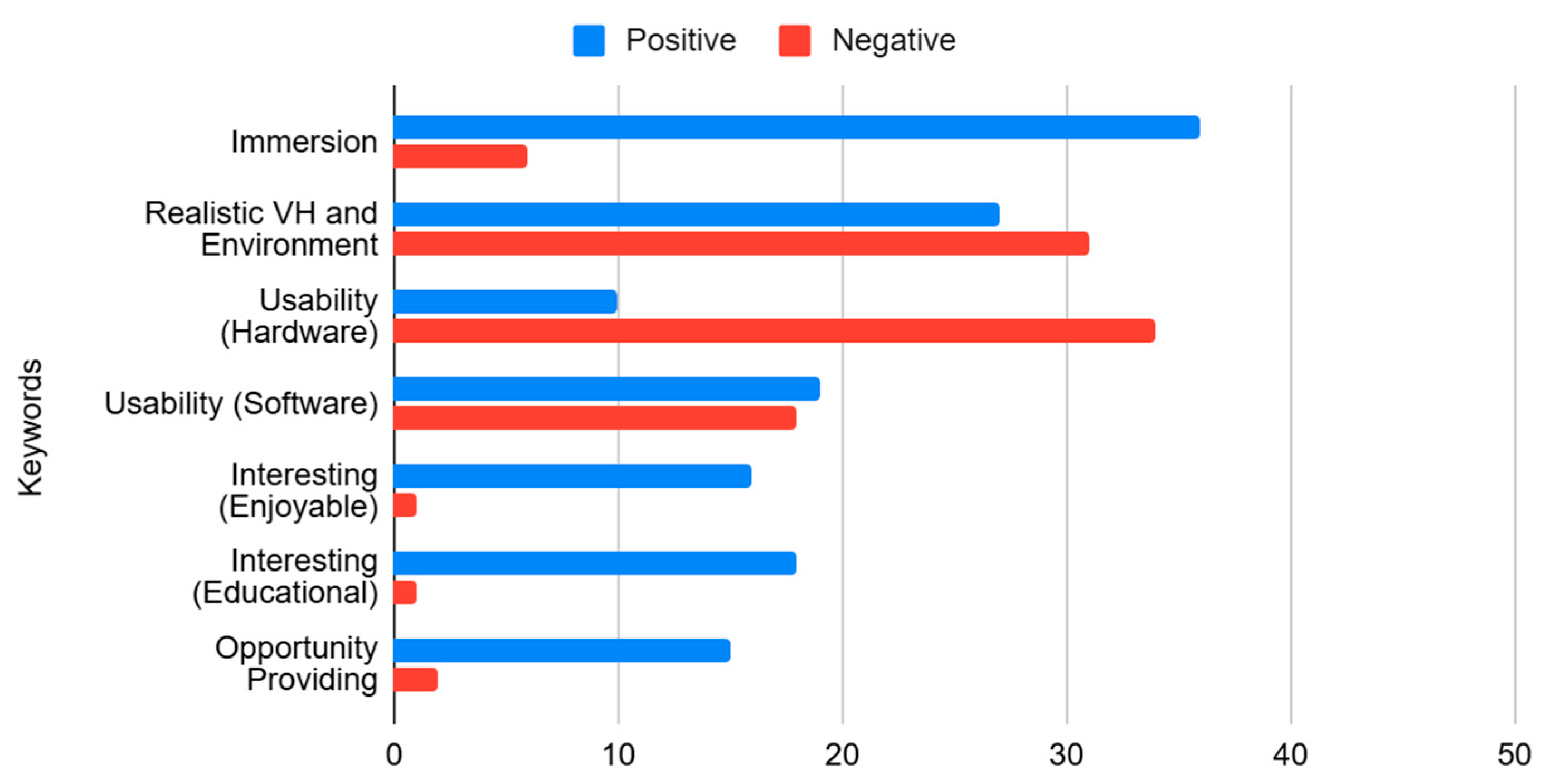

4.3. Satisfaction with EmpathyVR

- Immersive: Phrases indicating a feeling of presence.

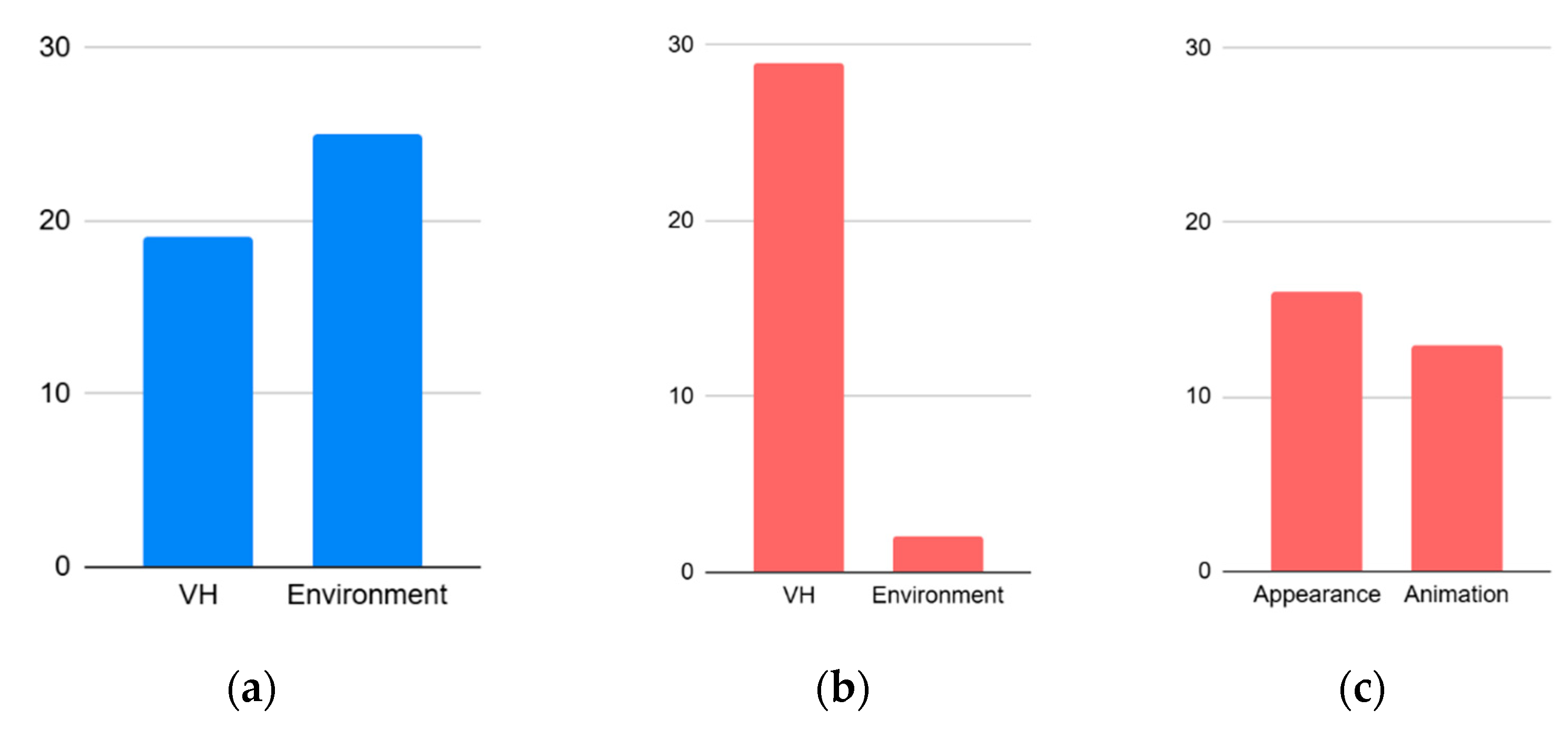

- Realistic Virtual Humans and Environment: Phrases describing an accurate representation similar to the real world.

- Usability—Hardware: Phrases signifying that the devices were useful.

- Usability—Software: Phrases indicating that the content fulfilled its intended purpose.

- Interesting and Enjoyable: Phrases suggesting that the content was entertaining.

- Interesting and Educational: Phrases referring to engaging and valuable content for empathy detection and learning.

- Opportunity Providing: Phrases indicating that the content facilitated knowledge growth and served as a platform for development and empathy detection.

4.4. Relationship Between Familiarity with IVR and Embodiment

The participants’ prior IVR experience is independent of their embodiment level during role-play with VHs in EmpathyVR.

4.5. Relationship Between Immersion and Satisfaction

The participants’ immersion and satisfaction levels are independent of each other during role-play with VHs in EmpathyVR.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Role-Playing with VHs in IVR-Based PTA

5.2. Prior IVR Experience and Embodiment

5.3. Level of Immersion and Satisfaction

5.4. Implications

5.5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IVR | Immersive virtual reality |

| IVE | Immersive virtual environment |

| VH | Virtual Human |

| PTA | Psychological testing and assessment |

| VHI | Virtual Human Interaction |

| PaNES | Positive and Negative Empathy Scale |

| CASES | Cognitive, Affective, and Somatic Empathy Scale |

| MESA | Multidimensional Empathy Scale for Adolescents |

| HMD | Head-mounted display |

| MBTI | Myers-Briggs type indicator |

| MSIT | Ministry of Science and ICT |

| ITRC | Information Technology Research Center |

| IITP | Institute for Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation |

Appendix A

| Scenario | Questions | Possible Answers | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Positive Situation | ||

| 1. Which one of the following did you experience more while talking with Sangmin? | (a) I easily understood what Sangmin was feeling | (a) = 1 point for C (b) = 1 point for A | |

| 2. From the list of provided emotion words, choose the emotion you felt after listening to Sangmin’s story? (up to five words) | Delighted, upset, happy, depressed, sad, excited, worried, proud, excited, impressed, blessed, uncertain, embarrassed, interested, pitiful, admired | Five relevant words = 1 point for A | |

| 3. How much do you agree with “I was excited and happy as if I confessed and was accepted”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for A | |

| 4. How much do you agree with “I tried to imagine what Sangmin was feeling as much as possible when I was hearing his story”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for C | |

| Scenario | Questions | Possible answers | Scoring |

| #1 | Negative situation | ||

| 5. Which one of the following did you experience more while talking with Sihwan? | (a) I easily understood what Sihwan was feeling (b) I felt what Sihwan was feeling | (a) = 1 point for C (b) = 1 point for A | |

| 6. From the list of emotion words, choose the emotion you felt after listening to Sihwan’s story? (up to five words) | Delighted, upset, happy, depressed, sad, excited, worried, proud, excited, impressed, blessed, uncertain, embarrassed, interested, pitiful, admired | Five relevant words = 1 point for A | |

| 7. How much do you agree with “I felt down and sad as if I confessed and was rejected”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for A | |

| 8 How much do you agree with “I tried to imagine what Sihwan was feeling as much as possible when I was hearing his story”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for C | |

| 9. There are gift icons that you can give to your friends. Choose the person you want to give the gift icon to: Sangmin or Sihwan. | Sangmin or Sihwan | Sangmin = 1 point for P Sihwan = 1 point for N | |

| 10. When you heard the story of Sangmin who confessed successfully and a friend Sihwan whose confession was rejected, whose story did you want to hear more? | Sangmin or Sihwan | Sangmin = 1 point for P Sihwan = 1 point for N | |

| 11. Whose feelings influenced you more—Sangmin whose confession got accepted or Sihwan whose confession got rejected? | Sangmin or Sihwan | Sangmin = 1 point for P Sihwan = 1 point for N | |

| 12. When there are many people who are happy like Sangmin who made a successful confession, and one person who is having a hard time like Sihwan whose confession was rejected; whose story do you want to hear more, from (Sangmin) group or (Sihwan)? [Show images of several Sangmins and one Sihwan.] | Sangmin or Sihwan | Sangmin = 0.5 point for M Sihwan = 0.5 point for m | |

| 13. When there is one person who is happy like Sangmin who confessed successfully, and there are many people who are struggling like Sihwan whose confession was rejected, which one do you want to hear more from (Sihwan) group or (Sangmin)? [Show images of several Sihwans and one Sangmin] | Sangmin or Sihwan | Sangmin = 0.5 point for m Sihwan = 0.5 point for M | |

| Scenario | Questions | Possible answers | Scoring |

| #2 | Positive situation | ||

| 1. Which one of the following did you experience more while talking with Jaehong? | (a) I easily understood what Jaehong was feeling (b) I felt what Jaehong was feeling | (a) = 1 point for C (b) = 1 point for A | |

| 2. From the list of provided emotion words, choose the emotion you felt after listening to Jaehon’s story? (up to five words) | Delighted, upset, happy, depressed, sad, excited, worried, proud, excited, impressed, blessed, uncertain, embarrassed, interested, pitiful, admired | Five relevant words = 1 point for A | |

| 3. How much do you agree with “I was excited and happy as if I won first place in the competition”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for A | |

| Negative situation | |||

| 5. Which one of the following did you experience more while talking with Juyeon? | (a) I easily understood what B was feeling (b) I felt what B was feeling | (a) = 1 point for C (b) = 1 point for A | |

| 6. From the list of emotion words, choose the emotion you felt after listening to Juyeon’s story? (up to five words) | Delighted, upset, happy, depressed, sad, excited, worried, proud, excited, impressed, blessed, uncertain, embarrassed, interested, pitiful, admired | Five relevant words = 1 point for A | |

| 7. How much do you agree with “I felt down and sad as if I lost in the first round”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for A | |

| 8 How much do you agree with “I tried to imagine what Juyeon was feeling as much as possible when I was hearing his story”? | 5-rating scale (1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree) | 4&5 = 1 point for C | |

| 9. There is a glass of water that you can give to your friends. Choose the person you want to give a glass of water to: Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong = 1 point for P Juyeon = 1 point for N | |

| 10. When you heard the story of Jaehong who won first place in the competition and Juyeon who lost in the first round, whose story did you want to hear more? | Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong = 1 point for P Juyeon = 1 point for N | |

| 11. Among the stories of Jaehong who won first place in the competition or a friend Juyeon who lost in the first round, whose feelings influenced you more? | Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong = 1 point for P Juyeon = 1 point for N | |

| 12. When there are many people who are happy like Jaehong who won first place in the competition and one person who is having a hard time like Juyeon who lost in the first round, whose story do you want to hear more from (Jaehong) group or (Juyeon)? [Show images of several Jaehongs and one Juyeon] | Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong = 0.5 point for M Juyeon = 0.5 point for m | |

| 13. When there is one person who is happy like Jaehong who won the first place in the competition, and there are many people who are struggling like Juyeon who lost in the first round, which one do you want to hear more from (Juyeon) group or (Jaehong)? [Show images of several Juyeons and one Jaehong] | Jaehong or Juyeon | Jaehong = 0.5 point for m Juyeon = 0.5 point for M | |

| Scenario | Questions | Possible answers | Scoring |

| #3 | Negative situation for minority and positive situation for majority | ||

| 1. Which one of the following did you experience more? | (a) I can better understand the positive feelings of celebrating the birthday (majority) than the negative feeling of losing a cell phone (Eunwoo) (b) I can better understand the negative feeling of losing a cell phone (Eunwoo) than the positive feelings of celebrating the birthday (majority) | (a) = 1 point for M (b) = 1 point for m | |

| 2. Which one of the following did you want to do more? | (a) I want to help Eunwoo to feel better (b) I want to celebrate the birthday with them | (a) = 1 point for m (b) = 1 point for M | |

| 3. Which one of the following did you feel more? | (a) I feel bad for Eunwoo (b) I feel good for students who are celebrating the birthday | (a) = 1 point for m (b) = 1 point for M | |

| 4. Which one of the following did you want to do more? | (a) I want to do what Eunwoo wants to do with me (b) I want to do what students who are celebrating the birthday want to do with me | (a) = 1 point for m (b) = 1 point for M | |

| Positive situation for minority and negative situation for majority | |||

| 5. Which one of the following did you experience more? | (a) I can better understand the negative feelings of losing in a soccer competition (majority) than the positive feeling of winning in a running competition (Woohyun) (b) I can better understand the positive feeling of winning in a running competition (Woohyun) than the negative feelings of losing in a soccer competition (majority) | 5. Which one of the following did you experience more? | |

| 6. Which one of the following did you want to do more? | (a) I want to congratulate Woohyun (b) I want to help students who lost in a soccer competition | (a) = 1 point for M (b) = 1 point for m | |

| 7. Which one of the following did you feel more? | (a) I feel good for Woohyun (b) I feel bad for the students who lost in a soccer competition | (a) = 1 point for M (b) = 1 point for m | |

| 8. Which one of the following did you want to do more? | (c) I want to do what students who lost in a soccer competition want to do with me (d) I want to do what Woohyun wants to do | (a) = 1 point for M (b) = 1 point for m | |

Appendix B

| Category | Keywords/Phrases |

|---|---|

| Immersion | “Immersive”, “I felt like real situation”, “Sense of immersion quite high”, “Easy to immerse in the situation that could have existed in reality”, “Well immersed”, “Allowing people to immerse themselves much more quickly”, “Good to think as another world and immerse”, “Immersed”, “ Immersing in situation”, “Like facing real situation”, “Able to experience actual situation in virtual reality”, “People appeared seem to be real and easily immersed in them”, “Immersive due to real human voice”, “See and feel it with own eyes”, “Making it immersed”, “Allows as if I am experiencing the situation myself” |

| Realistic VH and Environment | “Experiencing real school”, “Made based on things that can be experienced in reality”, “Quite real”, “Students similar to reality”, “Like reality”, “Felt like real”, Characters felt alive”, “Virtual space felt real”, “Act in real situation”, “Experiencing real school”, “Things that could happen in real situation”, “Felt like a real situation”, “Expressed realistic and well”, “Felt realistic”, “Made based on things that can be experienced in reality”, “More realistic”, “Liked compositions of situation that could actually occur”, “Realistic interaction”, “The situation seemed real”, “Like facing real situation”, “Characters”, “Quality”, “Alive characters”, “Friends”, “People”, “Human”, “Students”, “Character movements”, “Facial expressions”, “Appearances”, “People appeared seemed real”, “Disappointing” |

| Opportunity Providing | “Could easily find out my empathy type”, “Beneficial to learn empathy through simulation”, “Able to experience technology that never encountered before”, “Able to know empath type”, “Able to know emotional type”, “Able to pick objects felt like reality”, “Various situation and options gave opportunity to think about how to act in real situation”, “Was good to do it in a situation that could happen around people”, “Was able to answer with more immersion than by understanding the situation in writing”, “Variety of options of choosing emotions”, “Able to conduct test”, “Decide options”, “Opportunity providing”, “Being able to choose multiple emotions”, “Empathy Increases”, “Being able to sympathize and understand emotions” |

| Interesting | “Fun”, “Nice to know empathy type”, “Amazing to enter inside VR”, “Was great being able to make decisions across multiple situations”, “Liked compositions of situation that could actually occur”, “Being able to know empathy was fun” “New and fun”, “More realistic and interesting than regular one”, “Less boring”, “Nice and fun content”, “Enjoy different type of test” |

| Usability | “Useful”, “Good and easy to use”, “Able to get used to it quickly”, “Easy interface”, “Able to contrate well and move freely”, “Easy operation”, “Simple and easy operation”, “Heavy device”, “Device”, “VR device”, “Felt dizzy”, “Limited hand motion”, “Headset”, “Poor screen quality”, “VR machine” |

| Role-Play | “Experiencing the actual situation”, “As a student myself”, “Able to sympathize more”, “Simulation”, “Asking opinion after the situation presented made more immersed”, “Experience the situation and judge”, “Feel as if experiencing the situation myself”, “Faced a real situation rather than reading” |

| Negative | “Frustrating”, “Awkward”, “Uncomfortable”, “Unnatural”, “Scared”, “Bad”, “Inconvenient”, “Not realistic”, “Difficult”, “Bad quality”, “Heavy”, “Poor”, “Low”, “Disappointing”, “Hurt”, “Ugly” |

| Positive | “Pretty”, “Good”, “Realistic”, “Good quality”, “Real”, “Interesting”, “Fun”, “Like”, “High sense”, “Nice”, “Like reality”, “Amazing”, “Easy”, “Alive”, “Able to enjoy”, “Seemed real”, “Less boring”, “Familiar”, “Refreshing” |

References

- Armaou, M.; Konstantinidis, S.; Blake, H. The Effectiveness of Digital Interventions for Psychological Well-Being in the Workplace: A Systematic Review Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Burger, H.; Arjadi, R.; Bockting, C.L.H. Effectiveness of digital psychological interventions for mental health problems in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, B.; Botella, C.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Baños, R.M. Virtual Reality and Anxiety Disorders Treatment: Evolution and Future Perspectives. In Virtual Reality for Psychological and Neurocognitive Interventions; Rizzo “Skip”, A., Bouchard, S., Eds.; Virtual Reality Technologies for Health and Clinical Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 47–84. ISBN 978-1-4939-9480-9. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, M.; Prada, R.; Santos, P.A.; Dias, J.; Jhala, A.; Mascarenhas, S. The Impact of Virtual Reality in the Social Presence of a Virtual Agent. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Virtual Event, 20–22 October 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, M.; Rossmy, B.; Neumann, D.P.; Streuber, S.; Schmidt, A.; Machulla, T.-K. A Human Touch: Social Touch Increases the Perceived Human-likeness of Agents in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, R.B.; McHugh, M.P. Development of parasocial interaction relationships. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1987, 31, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.R. The Limitations of Self-Report Measures of Non-Cognitive Skills. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-limitations-of-self-report-measures-of-non-cognitive-skills/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- NeuroLaunch Self-Report Measures in Psychology: Advantages, Limitations, and Applications. Available online: https://neurolaunch.com/self-report-measures-psychology/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Tourangeau, R.; Rips, L.J.; Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-521-57246-0. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, J.; Gustavson, A.R. The Science of Self-Report. APS Observer 1997. Available online: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/the-science-of-self-report (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Razavi, T. Self-Report Measures: An Overview; Discussion Papers in Accounting and Management Science; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Simms, L.J.; Zelazny, K.; Williams, T.F.; Bernstein, L. Does the number of response options matter? Psychometric perspectives using personality questionnaire data. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, P.; Aguado, D.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Abad, F.; Santamaría, P. New Trends in Digital Technology-Based Psychological and Educational Assessment. Psicothema 2023, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhammer, F.; Scherer, R.; Greiff, S. Editorial: Advancements in Technology-Based Assessment: Emerging Item Formats, Test Designs, and Data Sources. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Laine, T.H.; Suk, H.J.; Jo, Y.W. Using immersive virtual reality in testing empathy type for adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 16183–16197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, E.; Sofkova Hashemi, S.; Lundin, J. Fun and frustrating: Students’ perspectives on practising speaking English with virtual humans. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2170088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochimaru, M. Digital Human Models for Human-Centered Design. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2017, 29, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badler, N.I.; Phillips, C.B.; Webber, B.L. Simulating Humans: Computer Graphics, Animation, and Control; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-1-60129-867-866. [Google Scholar]

- Gratch, J.; Wang, N.; Okhmatovskaia, A.; Lamothe, F.; Morales, M.; Van Der Werf, R.J.; Morency, L.-P. Can Virtual Humans Be More Engaging Than Real Ones. In Human-Computer Interaction. HCI Intelligent Multimodal Interaction Environments; Jacko, J.A., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4552, pp. 286–297. ISBN 978-3-540-73108-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggioli, A.; Mantovani, F.; Castelnuovo, G.; Wiederhold, B.; Riva, G. Avatars in Clinical Psychology: A Framework for the Clinical Use of Virtual Humans. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2003, 6, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Shilling, R.; Forbell, E.; Scherer, S.; Gratch, J.; Morency, L.-P. Autonomous Virtual Human Agents for Healthcare Information Support and Clinical Interviewing. In Artificial Intelligence in Behavioral and Mental Health Care; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 53–79. ISBN 978-0-12-420248-1. [Google Scholar]

- Paulik, G.; Taylor, C.D.J. Imagery-Focused Therapy for Visual Hallucinations: A Case Series. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2024, 31, e2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.; Bouchard, S. (Eds.) Virtual Reality for Psychological and Neurocognitive Interventions. In Virtual Reality Technologies for Health and Clinical Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4939-9480-9. [Google Scholar]

- De Melo, C.M.; Gratch, J.; Marsella, S.; Pelachaud, C. Social Functions of Machine Emotional Expressions. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 1382–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiwald, J.P.; Schenke, J.; Lehmann-Willenbrock, N.; Steinicke, F. Effects of Avatar Appearance and Locomotion on Co-Presence in Virtual Reality Collaborations. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2021, Ingolstadt, Germany, 5–8 September 2021; pp. 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich, J.; Bailenson, J.N. Infinite Reality: Avatars, Eternal Life, New Worlds, and the Dawn of the Virtual Revolution; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M.; Usoh, M. Presence in Immersive Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality Annual International Symposium, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–22 September 1993; pp. 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kvapil Varšová, K.; Juřík, V. Using iVR to deliver optimal psychotherapy experience—Current perspectives on VRET for acrophobia. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1491622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, Z.; Ransom, S.; Xiao, A.; Huang, J. Therapy as an NLP Task: Psychologists’ Comparison of LLMs and Human Peers in CBT. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.02244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araiza, P.; Keane, T.L.; Beaudry, J.; Kaufman, J. Immersive Virtual Reality Implementations in Developmental Psychology. Int. J. Virtual Real. 2020, 20, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. Virtual Reality in Clinical Psychology. In Comprehensive Clinical Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 91–105. ISBN 978-0-12-822232-4. [Google Scholar]

- Elor, A.; Kurniawan, S. The Ultimate Display for Physical Rehabilitation: A Bridging Review on Immersive Virtual Reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2020, 1, 585993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöne, B.; Kisker, J.; Lange, L.; Gruber, T.; Sylvester, S.; Osinsky, R. The reality of virtual reality. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1093014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quah, T.C.S.; Lau, Y.; Ang, W.W.; Lau, S.T. Experiences of immersive virtual reality in healthcare clinical training for nursing and allied health students: A mixed studies systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 148, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, A.E.; Lumbye, A.; Schandorff, J.; Damgaard, V.; Glenthøj, L.B.; Nordentoft, M.; Mikkelsen, C.; Didriksen, M.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Vinberg, M.; et al. Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality (CAVIR): Associations with neuropsychological performance and activities of daily living in patients with mood or psychosis spectrum disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felnhofer, A.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Hauk, N.; Beutl, L.; Hlavacs, H.; Kryspin-Exner, I. Physical and social presence in collaborative virtual environments: Exploring age and gender differences with respect to empathy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. Empathy and embodied experience in virtual environment: To what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.M.; Rizzo, A.; Gratch, J.; Scherer, S.; Stratou, G.; Boberg, J.; Morency, L.-P. Reporting Mental Health Symptoms: Breaking Down Barriers to Care with Virtual Human Interviewers. Front. Robot. AI 2017, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Scherer, S.; DeVault, D.; Gratch, J.; Artstein, R.; Hartholt, A.; Lucas, G.; Marsella, S.; Nazarian, A.; Stratou, G.; et al. Detection and computational analysis of psychological signals using a virtual human interviewing agent. Virtual Real. 2014, 9, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, G.; Jung, S.; Lindeman, R.W. Evaluating Virtual Human Role-Players for the Practice and Development of Leadership Skills. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 658561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkaroski, D.; Mundy, M.; Dimmock, M.R. Immersive virtual reality simulated learning environment versus role-play for empathic clinical communication training. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 2022, 69, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbi, M.; Swart, M.; Keysers, C. Empathy for positive and negative emotions in the gustatory cortex. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reniers, R.L.E.P.; Corcoran, R.; Drake, R.; Shryane, N.M.; Völlm, B.A. The QCAE: A Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. J. Pers. Assess. 2011, 93, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, E. Development and initial validation of the Multidimensional Empathy Scale for Adolescents. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 26, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-S.; Jung, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, K. Controlling the Sense of Embodiment for Virtual Avatar Applications: Methods and Empirical Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e21879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewe, H.; Gottwald, J.M.; Bird, L.-A.; Brenton, H.; Gillies, M.; Cowie, D. My Virtual Self: The Role of Movement in Children’s Sense of Embodiment. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 28, 4061–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reallusion Character Creator 4. Available online: https://www.reallusion.com/character-creator/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Noitom Perception Neuron 3. Available online: https://www.noitom.com/perception-neuron-3 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Roth, D.; Lugrin, J.-L.; Latoschik, M.E.; Huber, S. Alpha IVBO—Construction of a Scale to Measure the Illusion of Virtual Body Ownership. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 2875–2883. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring Presence in Virtual Environments: A Presence Questionnaire. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehre, S.; O’Dwyer, M.; O’Malley, L.; Lee, N. The use of Net Promoter Score (NPS) to predict sales growth: Insights from an empirical investigation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.; Murphy, R.R. Hand gesture recognition with depth images: A review. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE RO-MAN: The 21st IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Paris, France, 9–13 September 2012; pp. 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, M.; Normand, J.-M.; Jeunet-Kelway, C.; Moreau, G. The sense of embodiment in Virtual Reality and its assessment methods. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1141683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagu, C.; AlSlaity, A.; Orji, R. EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interactions in Immersive Virtual and Augmented Reality: A Systematic Review. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 7, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.; Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VHs | Process | Story | Scene Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avatar | Virtual self [46] check in a mirror (male and female) |  (button text: complete verification)  | |

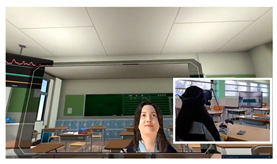

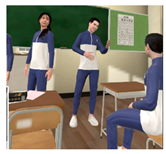

| One VH | Episode1. Positive | A boy has a crush on a girl and she likes him too. |  |

| Episode5. Negative | A boy was rejected by one of the girls he liked. |  | |

| Two VHs | Episode2. Positive and negative | A boy who lost and a girl who won in the badminton tournament. |  |

| Several VHs | Episode4. Positive for the majority vs. negative for the minority | A grumpy student who lost his phone, and a happy group for celebrating someone’s birthday. |  |

| Episode3. Positive for the minority vs. negative for the majority | A group of students lost a soccer game; a boy won a medal in a running competition. |  | |

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| World Design | |

| Environment | Classroom, school cafeteria |

| Virtual Humans (VH) | 11 virtual humans (VHs) performing 14 roles in the scenario |

| VH Creation | 3D digital humans created through image-based modeling in Character Creator v4.5 (Reallusion Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), using photographs of staff members in their early 20s |

| Animation | Character animations were recorded with actors using the Perception Neuron 3 motion capture system and AxisStudio 2.8 (Noitom Ltd., Beijing, China). The captured motion data was refined and processed in Maya 2021 (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and then applied to the characters in iClone 8 (Reallusion Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), with additional clean-up, polishing, and post-animation work. Missing animations were added, and unnecessary parts were removed to enhance realism and immersion. |

| Tools | |

| Character Creator 4.5 [47] | Character creation tool from Reallusion Inc. Version: 4.5 The software generates and customizes realistic 3D characters that are used across multiple 3D modeling platforms and game development engines. Scientific rationale: We tested Unreal Engine’s MetaHuman with FaceAR, Photogrammetry, Face Builder for Blender, and Headshot in Character Creation to generate an image-based 3D face model. Headshot in Character Creation was selected owing to its ability to quickly create realistic characters and its compatibility across multiple platforms. It is suitable for efficient integration into diverse 3D environments, as well as being fast, affordable, and less dependent on the skill of the user. |

| Perception Neuron 3 [48] | Motion capture system from Noitom Ltd. (Beijing, China). Version: 3.0 A full-body motion tracking system with 23 wireless inertial measurement sensors that are mounted on a custom suit, which the actor must equip while recording motions. Scientific rationale: We compared the HTC VIVE Tracker 3.0, Rococo Vision, and Perception Neuron 3 as potential motion capture technologies. Perception Neuron 3 tool was selected because of its portability, compact design, and cost-effectiveness compared to the other motion capture technologies. Moreover, it allows seamless transfer of recorded motion data to digital character animations. |

| Interaction Design | |

| Object manipulation | The user interacts with the world and objects using the IVR controllers, which enable basic actions such as grabbing, rotating, pointing, and clicking. |

| Seated IVR and control | Although EmpathyVR is used in a seated position, the user can move their upper body, hands, and shoulders, and rotate their head in IVR based on their physical movements. |

| Device and specifications | HTC VIVE Pro Eye (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan, Taiwan) was used for the HMD IVR display and to track participants’ head and eye movements. HTC VIVE Trackers (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan, Taiwan) were used to track the participants’ upper body and arm movements. |

| Empathy-type evaluation | After exploring each episode, the user answers questions (based on MESA), and their empathy type result is computed based on their responses. |

| Mean | Median | Mode | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | Range | 25th Percentile | 50th Percentile | 75th Percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 8.31 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 1.24 | 4.00 | 10.00 | 7.00 | 7.50 | 8.00 | 9.00 |

Experience/Embodiment | High Embodiment | Low Embodiment | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Experience | 19 | 13 | 32 | ||

| Low Experience | 44 | 23 | 67 | ||

| Total | 63 | 36 | 99 | ||

| Chi Square Test Result | Chi Square Statistic | p-Value | Degrees of freedom | Expected frequencies | |

| 0.149 | 0.700 | 1.0 | [[20.36, 11.64], [42.64, 24.36]] | ||

Immersion/Satisfaction | High Satisfaction | Low Satisfaction | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Immersion | 50 | 6 | 56 | ||

| Low Immersion | 24 | 19 | 43 | ||

| Total | 74 | 25 | 99 | ||

| Chi Square Test Result | Chi Square Statistic | p-Value | Degrees of freedom | Expected frequencies | |

| 12.72 | 0.000362 | 1.0 | [[41.86, 14.14], [32.14, 10.86]] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magar, S.T.; Suk, H.; Laine, T.H. User Experience of Virtual Human and Immersive Virtual Reality Role-Playing in Psychological Testing and Assessment: A Case Study of ‘EmpathyVR’. Sensors 2025, 25, 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25092719

Magar ST, Suk H, Laine TH. User Experience of Virtual Human and Immersive Virtual Reality Role-Playing in Psychological Testing and Assessment: A Case Study of ‘EmpathyVR’. Sensors. 2025; 25(9):2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25092719

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagar, Sunny Thapa, Haejung Suk, and Teemu H. Laine. 2025. "User Experience of Virtual Human and Immersive Virtual Reality Role-Playing in Psychological Testing and Assessment: A Case Study of ‘EmpathyVR’" Sensors 25, no. 9: 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25092719

APA StyleMagar, S. T., Suk, H., & Laine, T. H. (2025). User Experience of Virtual Human and Immersive Virtual Reality Role-Playing in Psychological Testing and Assessment: A Case Study of ‘EmpathyVR’. Sensors, 25(9), 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25092719