Design Analysis and Isotropic Optimization for Miniature Capacitive Force/Torque Sensor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analysis of the Deformable Part

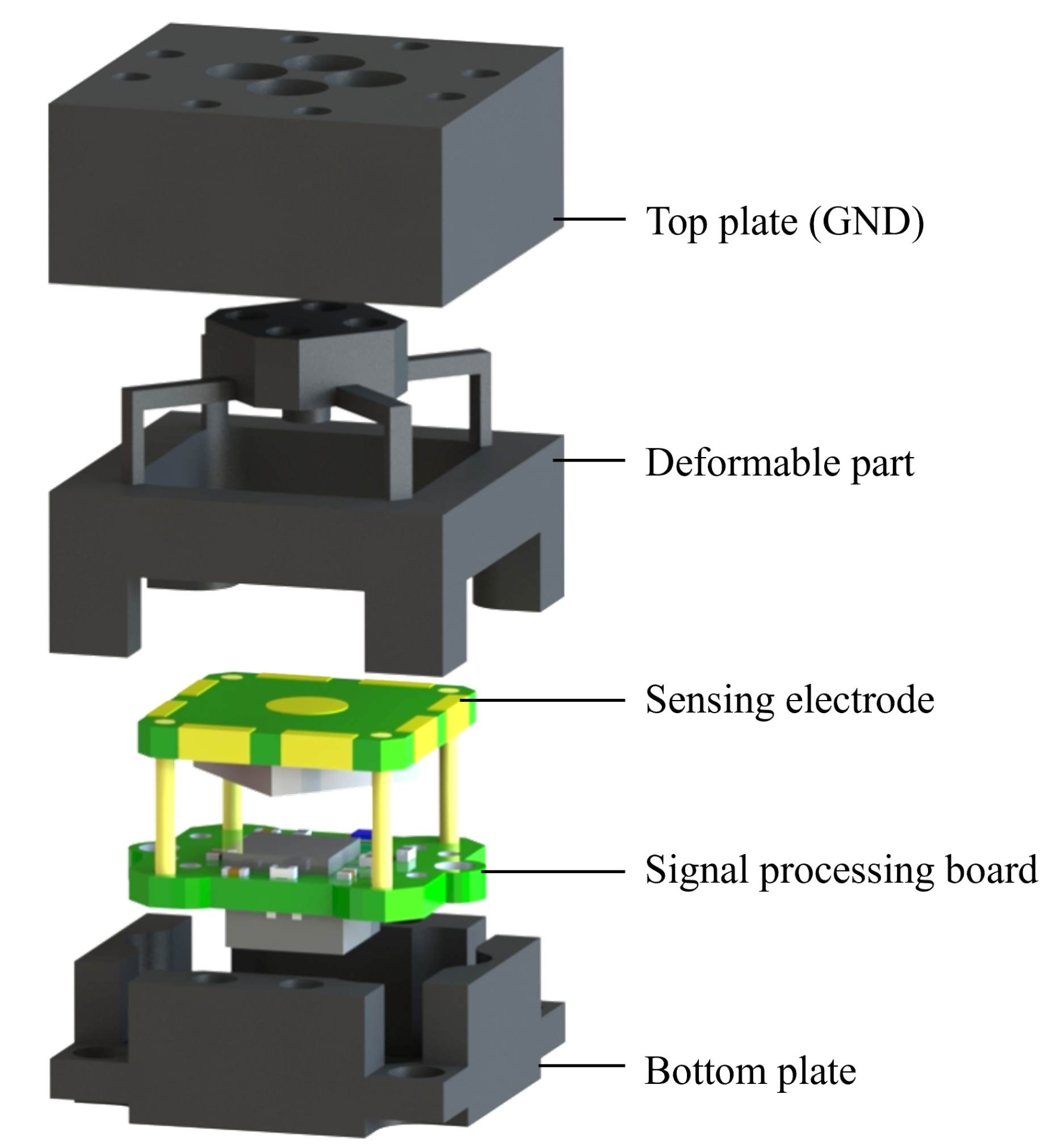

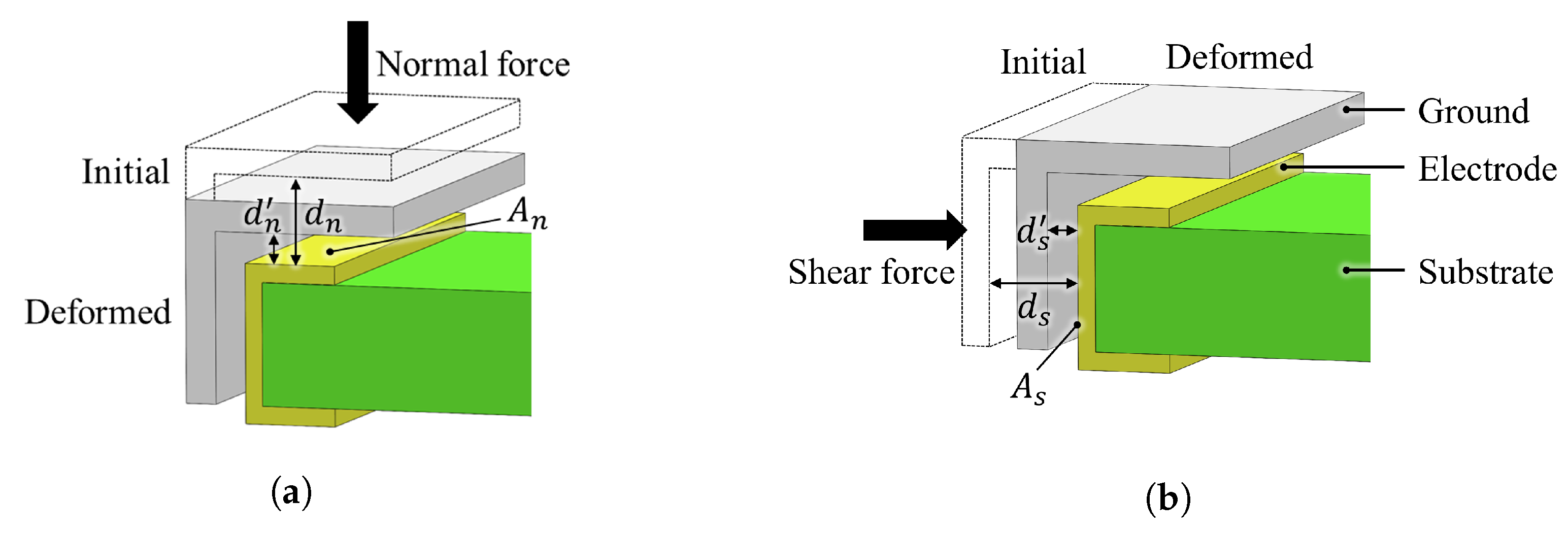

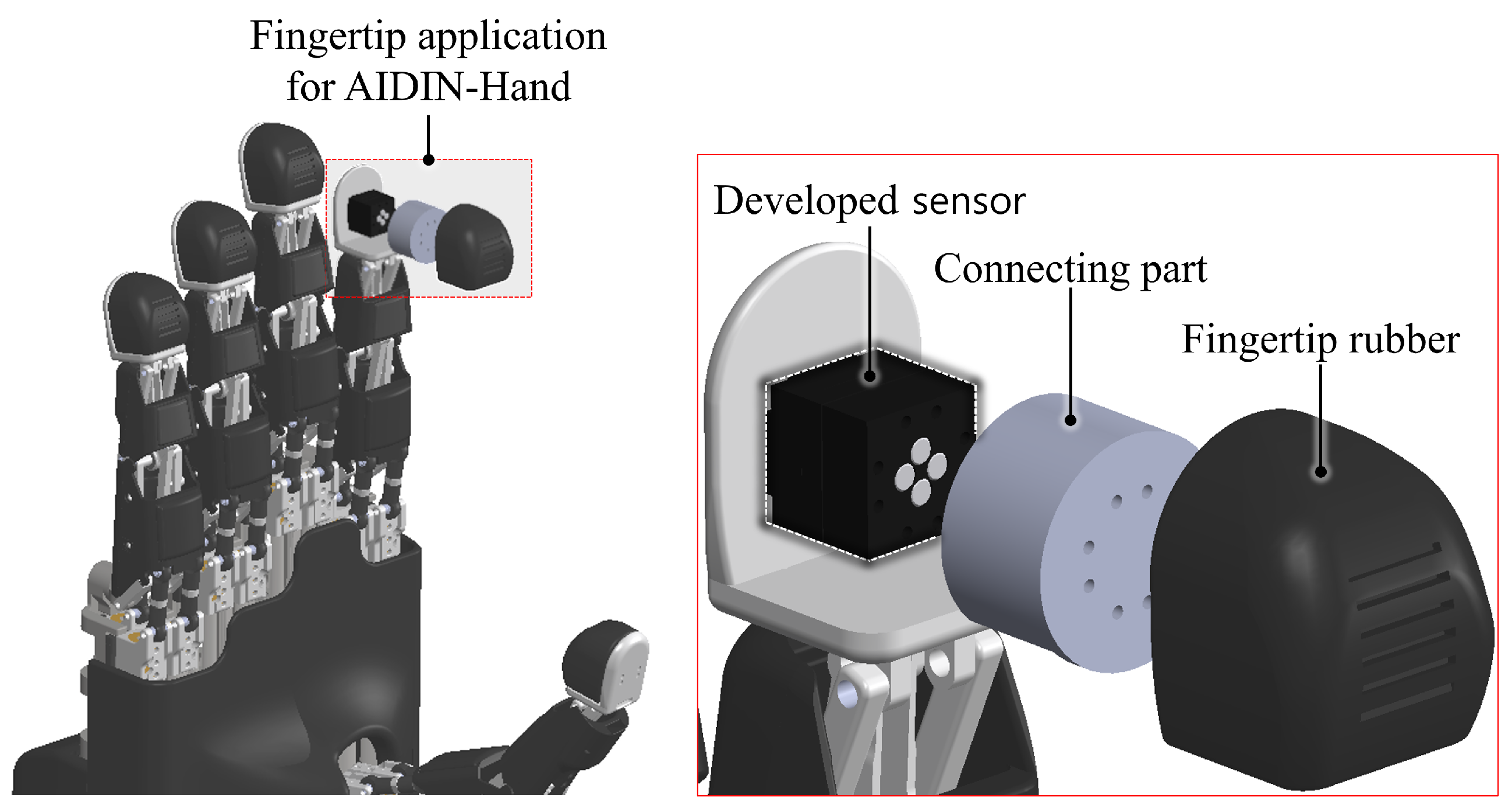

2.1. Capacitive Sensor Sensing Principle

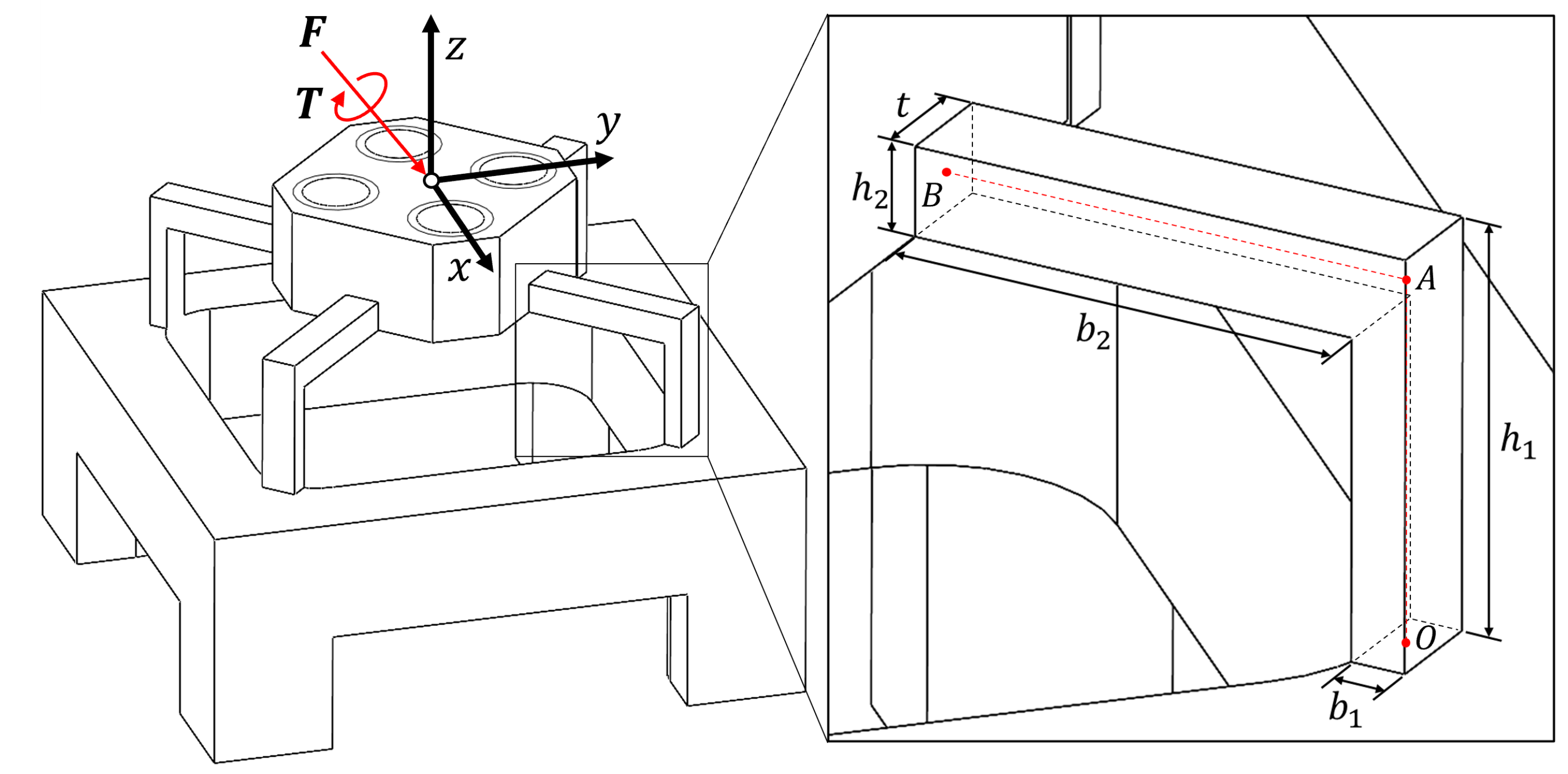

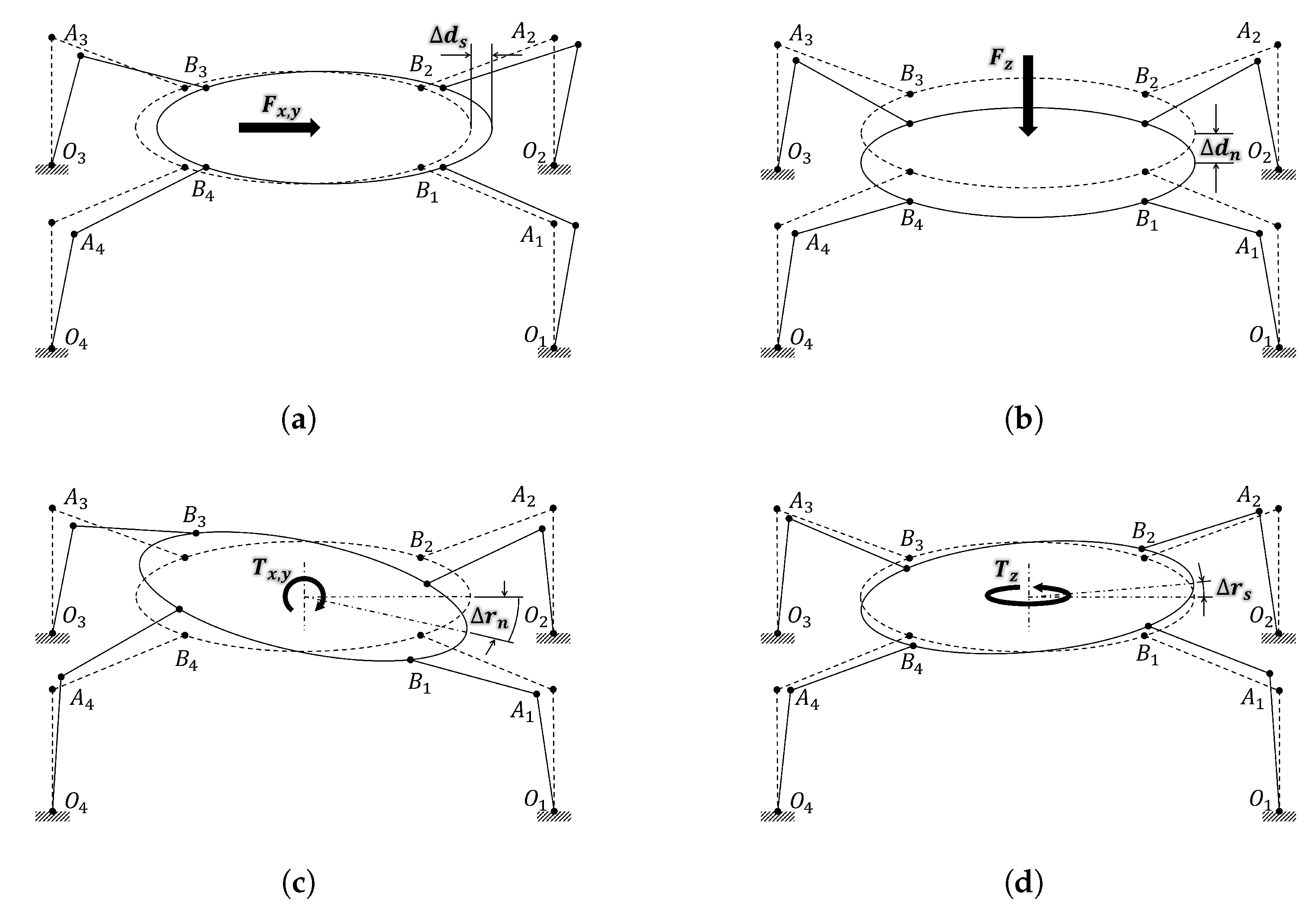

2.2. Analysis of Deformable Part

3. Isotropic Optimization

3.1. Deformable Part with Optimal Design

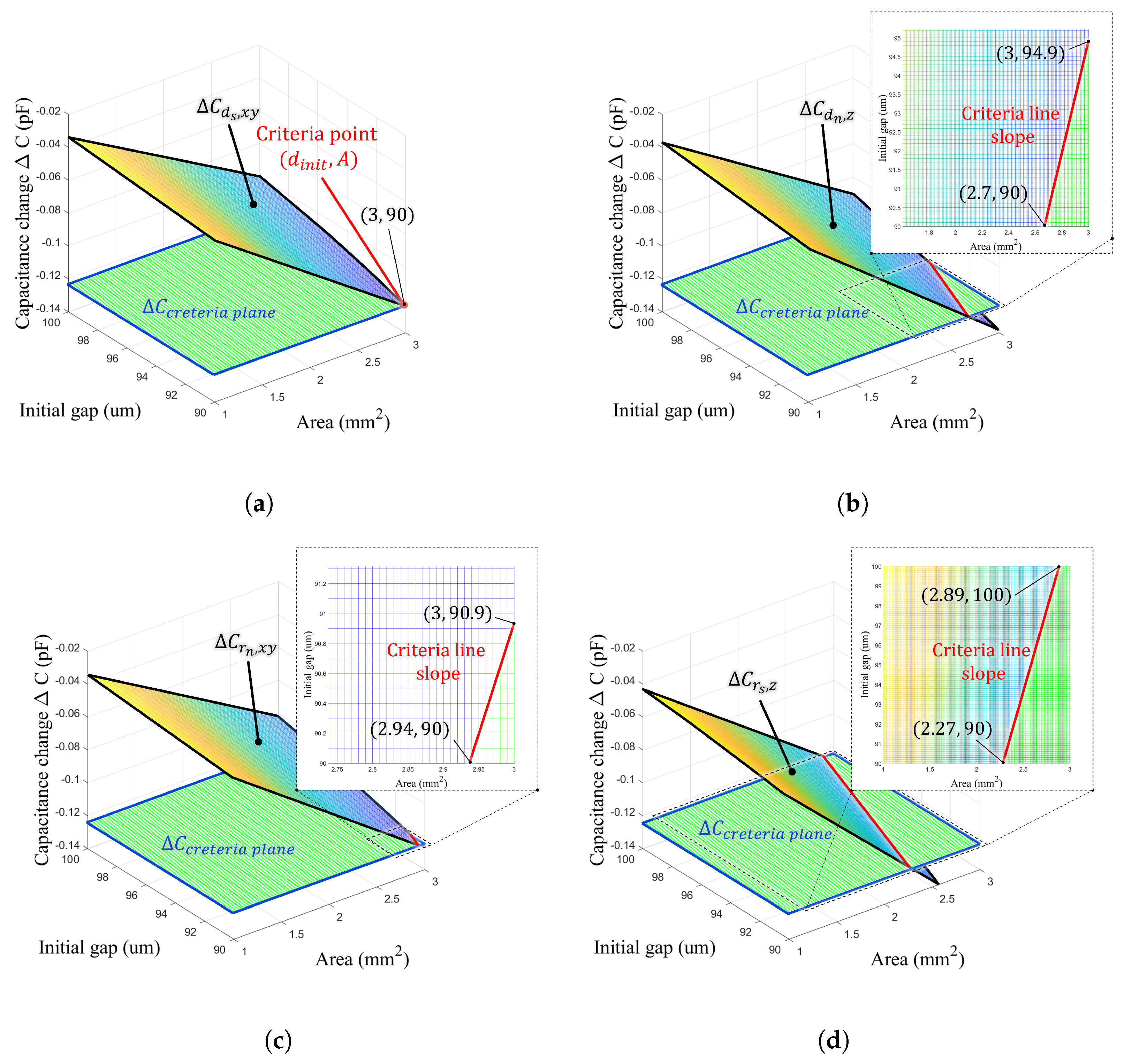

3.2. Sensing Electrode Design

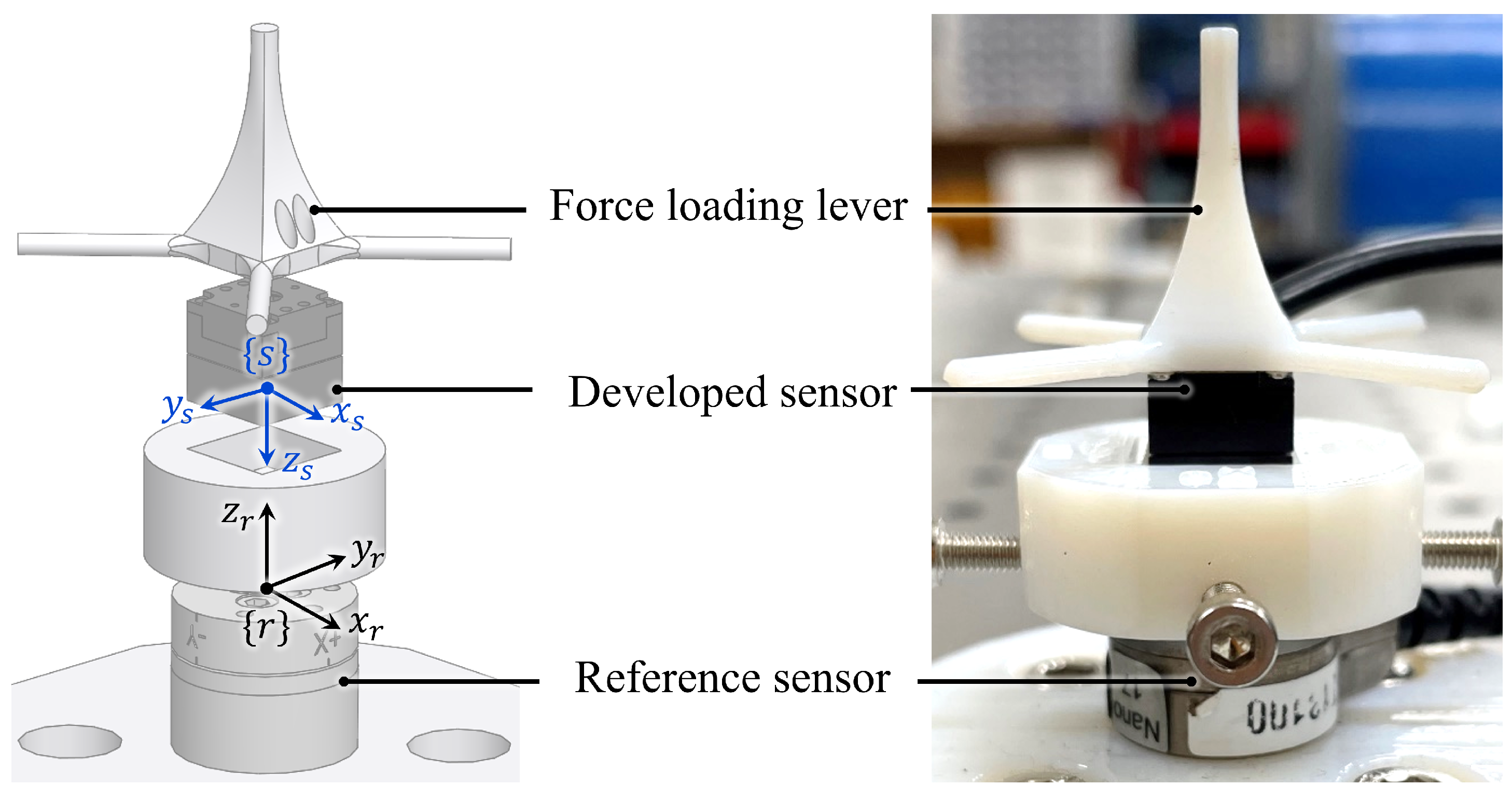

4. Development of Miniature Six-Axis F/T Sensor

4.1. Fabrication and Specification

4.2. Calibration Method

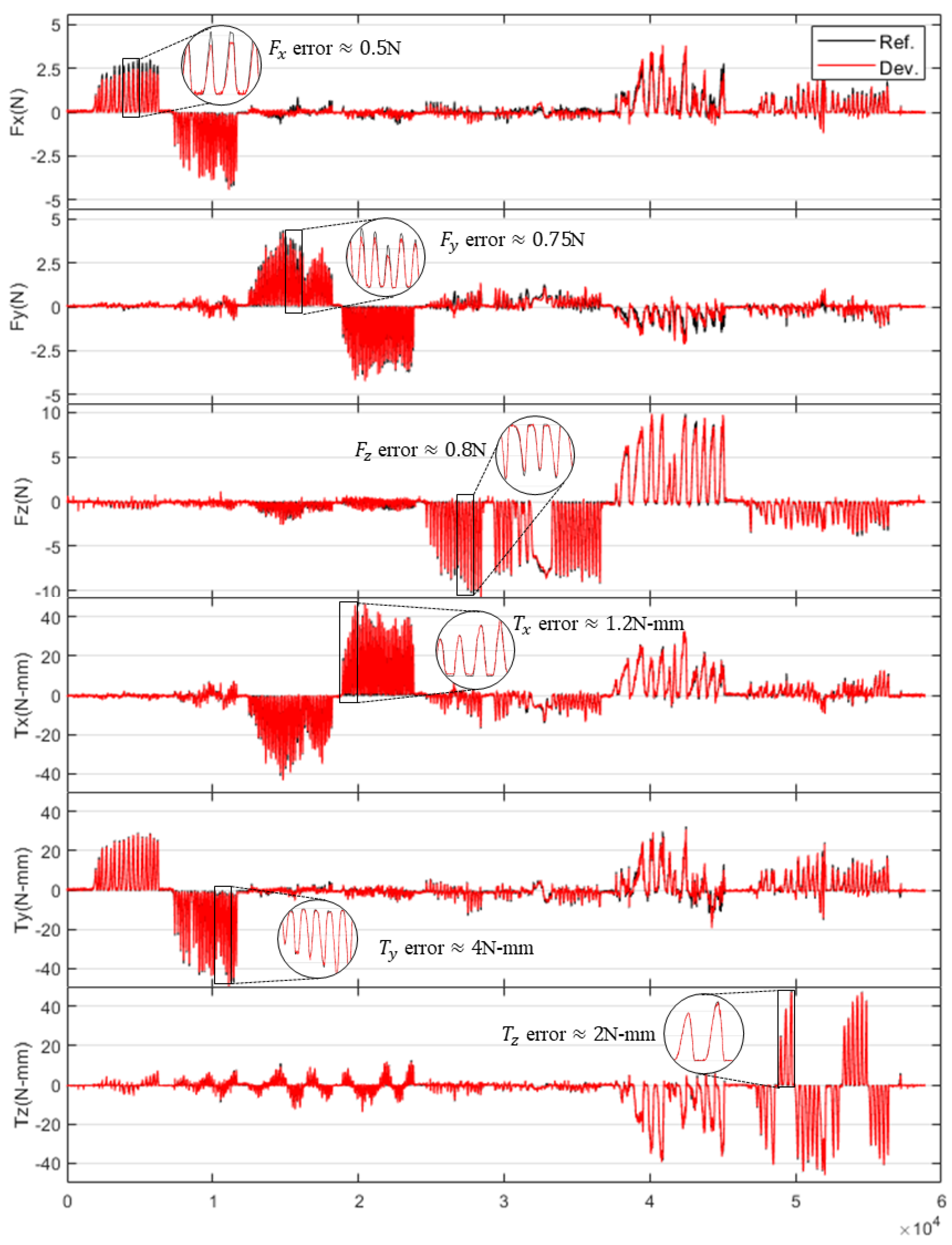

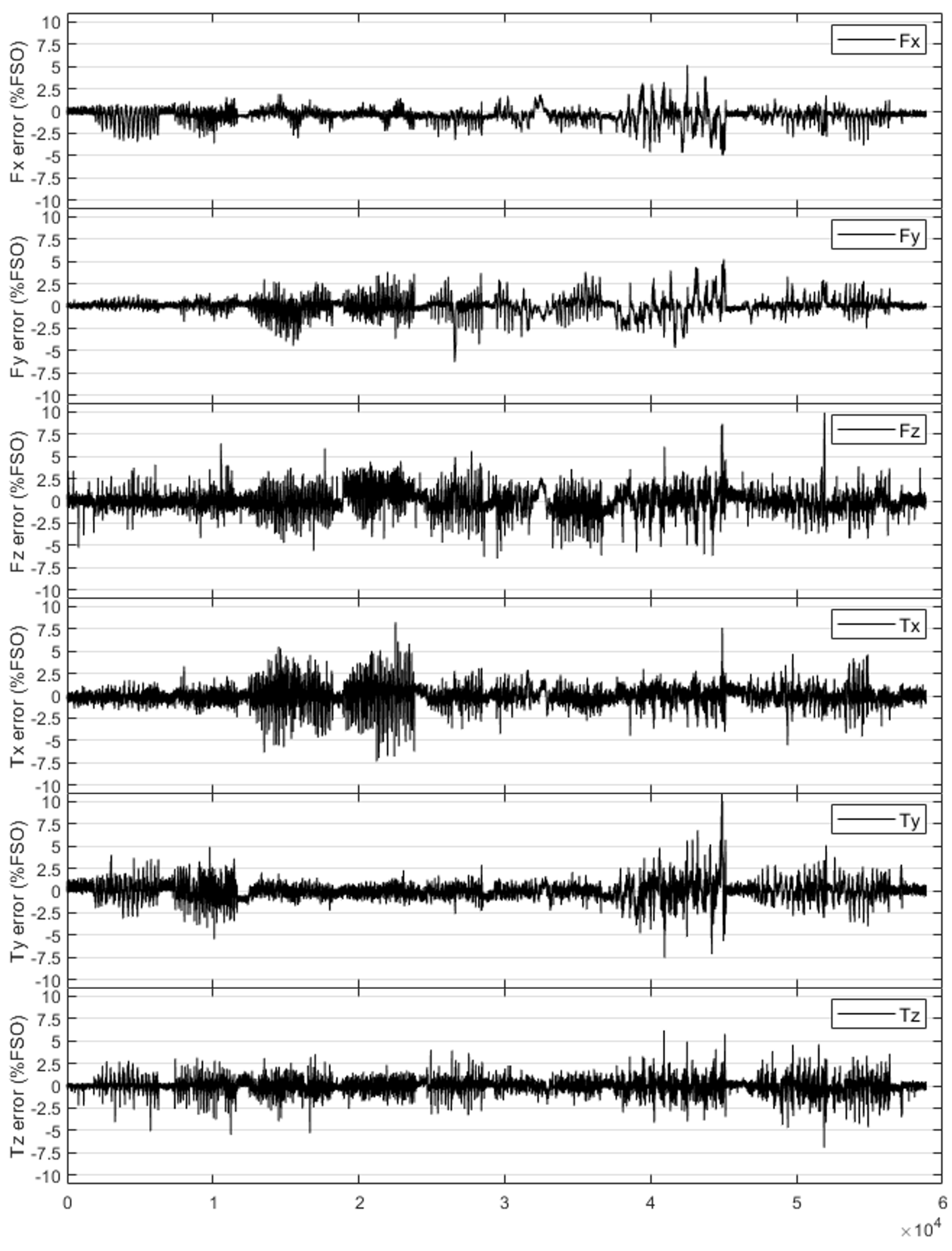

4.3. Calibration and Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merat, F. Introduction to robotics: Mechanics and control. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 1987, 3, 166. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis, A.; Siciliano, B.; De Luca, A.; Bicchi, A. An atlas of physical human—Robot interaction. Mech. Mach. Theory 2008, 43, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluethmann, W.; Ambrose, R.; Diftler, M.; Askew, S.; Huber, E.; Goza, M.; Rehnmark, F.; Lovchik, C.; Magruder, D. Robonaut: A robot designed to work with humans in space. Auton. Robot. 2003, 14, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-L.; Ahn, K.-H.; Song, J.-B. Direct teaching algorithm based on task assistance for machine tending. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), Xian, China, 19–22 August 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 861–866. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchi, A.; Salisbury, J.K.; Brock, D.L. Contact sensing from force measurement. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1993, 12, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, H.; Komatsu, T.; Uchiyama, K. Dexterous anthropomorphic robot hand with distributed tactile sensor: Gifu hand ii. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2002, 7, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Nguyen, K.C.; Perdereau, V.; Bimbo, J.; Back, J.; Godden, M.; Seneviratne, L.D.; Althoefer, K. Finger contact sensing and the application in dexterous hand manipulation. Auton. Robot. 2015, 39, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. Development and kinematics/statics analysis of rigid-flexible-soft hybrid finger mechanism with standard force sensor. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.; Jeong, H.; Do, H.; Park, J.; Park, C. Six-axis force/torque fingertip sensor for an anthropomorphic robot hand. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 5566–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchi, A. A criterion for optimal design of multi-axis force sensors. Robot. Auton. Syst. 1992, 10, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Isotropy analysis of redundant parallel six-axis force sensor. Mech. Mach. Theory 2015, 91, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, T. Isotropy optimization of six-axis capacitive force sensor with a large moment-to-force ratio. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M.; Liang, Q.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, R.; Ai, Z.; Su, F. Design and optimization of a novel capacitive six-axis force/torque sensor based on sensitivity isotropy. Measurement 2022, 203, 111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.-H. Shape optimization of a mechanically decoupled six-axis force/torque sensor. Sensors Actuators Phys. 2014, 209, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-R.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, U.; Gulrez, T.; Yoon, W.J.; Hannaford, B. A laparoscopic grasping tool with force sensing capability. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2016, 21, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, D.-Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, H.R. Ultra-thin joint torque sensor with enhanced sensitivity for robotic application. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 5873–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Design of a novel six-axis wrist force sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.W.; Na, K.S.; Kang, D.I. Design and evaluation of a six-component load cell. Measurement 2002, 32, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Kazerooni, A. Improving the coupling errors of a Maltese cross-beams type six-axis force/moment sensor using numerical shape-optimization technique. Measurement 2018, 126, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.A.; Tzo, H.L. A novel six-component force sensor of good measurement isotropy and sensitivities. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2002, 100, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobontiu, N. Compliant Mechanisms: Design of Flexure Hinges; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.-Y.; Youn, J.-H.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, U.; Kyung, K.-U. Development of a three-axis monolithic flexure-based ground reaction force sensor for various gait analysis. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 4118–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Bayo, E.; Palma-Villalon, E. A Systematic Design Procedure to Minimize a Performance Index for Robot Force Sensors. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1991, 113, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, Y.N.M.; Hakomori, K. Evaluation of the robot force sensor structure using singular value decomposition. Adv. Robot. 1990, 5, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M.; Luo, Q.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, J. Modeling for elastomer displacement analysis of capacitive six-axis force/torque sensor. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 22, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.Y.; Laws, S.; y Baena, F.R. Six-axis force/torque sensors for robotics applications: A review. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, 27238–27251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.S.; Kim, U.; Kang, G.; Seo, J.K.; Choi, H.R. Multi-axial force/torque sensor calibration method based on deep-learning. IEEE Sensors J. 2018, 18, 5485–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Choi, K.; Park, S.J.; Park, C.H.; Choi, H.R.; Kim, U. Rugged and compact three-axis force/torque sensor for wearable robots. Sensors 2021, 21, 2770–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, W.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, U. Automated Calibration Robotic System Capable of Producing Versatile Force Combinations for Multiaxis Force/Torque Sensors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 7335–7344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition Number | t | Unit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.261 | 0.49 | 1.15 | 3.45 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 10 × 10 × 10 | mm |

| Force | 15 | N |

| Torque | 75 | N-mm |

| Communication | CAN | |

| Sampling rate | 100 | Hz |

| Accuracy | Linearity | Resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 98.97 | 98.42 | 0.74 | |

| 98.87 | 98.23 | 0.77 | |

| 98.23 | 97.59 | 0.39 | |

| 99.37 | 99.12 | 0.52 | |

| 99.38 | 99.09 | 0.34 | |

| 99.53 | 99.33 | 0.22 |

| Quantity | Value | unit |

|---|---|---|

| Relative error of forces | 0.16, 0.18, 0.24 | %FSO |

| Relative error of torques | 0.88, 0.90, 0.67 | %FSO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.Y.; Sim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Seok, D.; Shim, J.; Choi, H.R. Design Analysis and Isotropic Optimization for Miniature Capacitive Force/Torque Sensor. Sensors 2025, 25, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030940

Lee SY, Sim JY, Kim YB, Seok D, Shim J, Choi HR. Design Analysis and Isotropic Optimization for Miniature Capacitive Force/Torque Sensor. Sensors. 2025; 25(3):940. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030940

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seung Yeon, Jae Yoon Sim, Yong Bum Kim, Dongyeop Seok, Jaeyoon Shim, and Hyouk Ryeol Choi. 2025. "Design Analysis and Isotropic Optimization for Miniature Capacitive Force/Torque Sensor" Sensors 25, no. 3: 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030940

APA StyleLee, S. Y., Sim, J. Y., Kim, Y. B., Seok, D., Shim, J., & Choi, H. R. (2025). Design Analysis and Isotropic Optimization for Miniature Capacitive Force/Torque Sensor. Sensors, 25(3), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030940