Phase Measuring Deflectometry for Wafer Thin-Film Stress Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

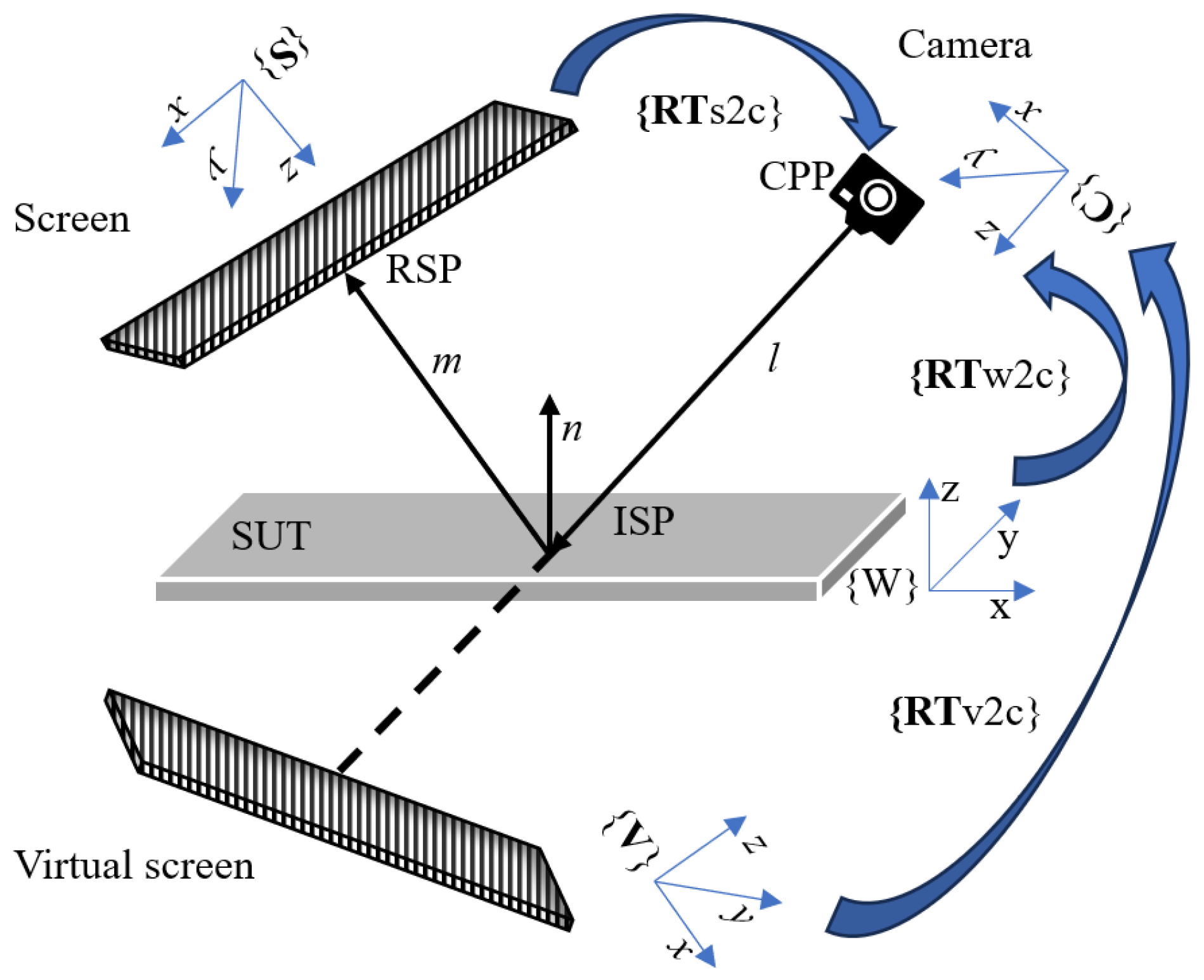

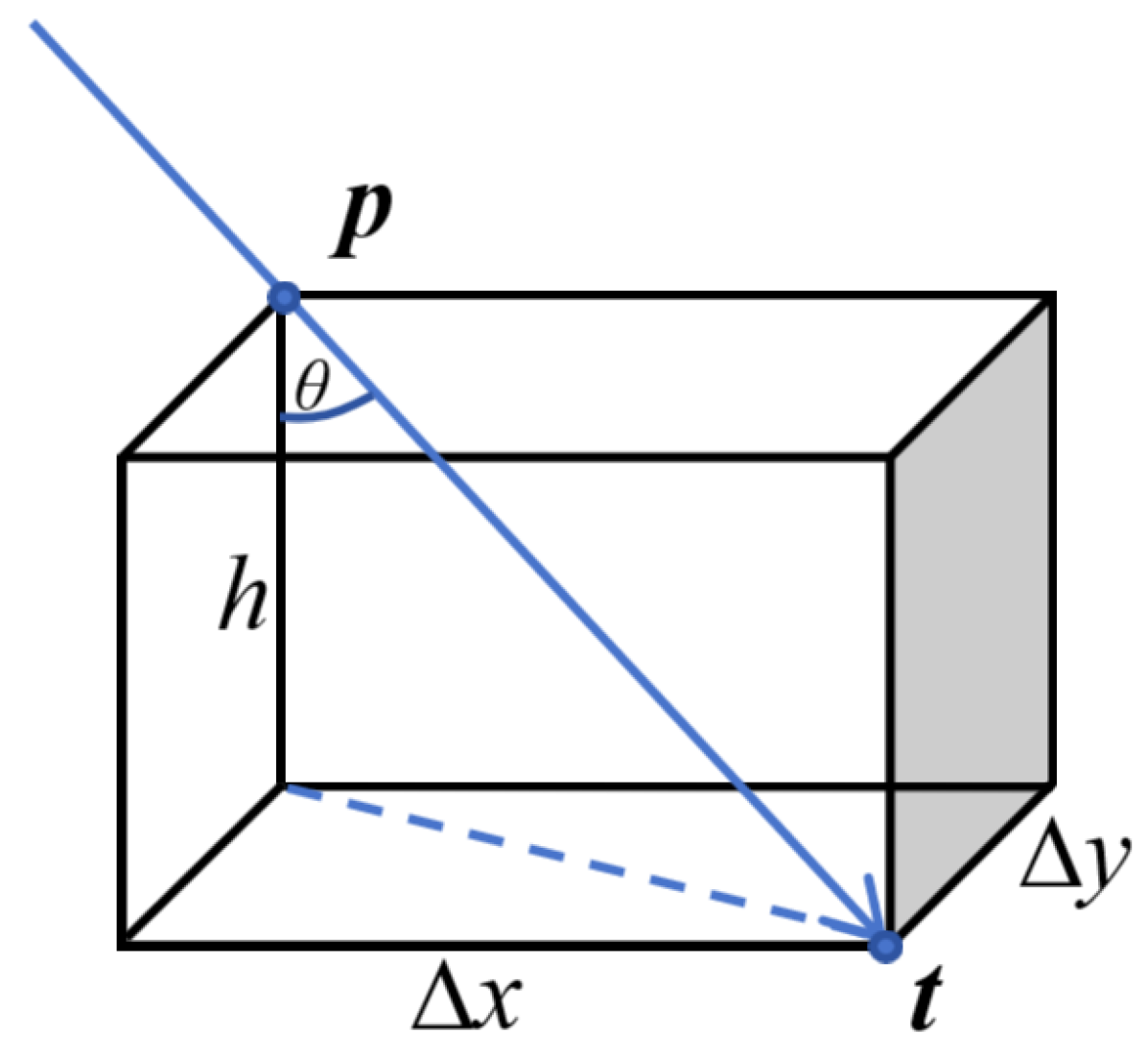

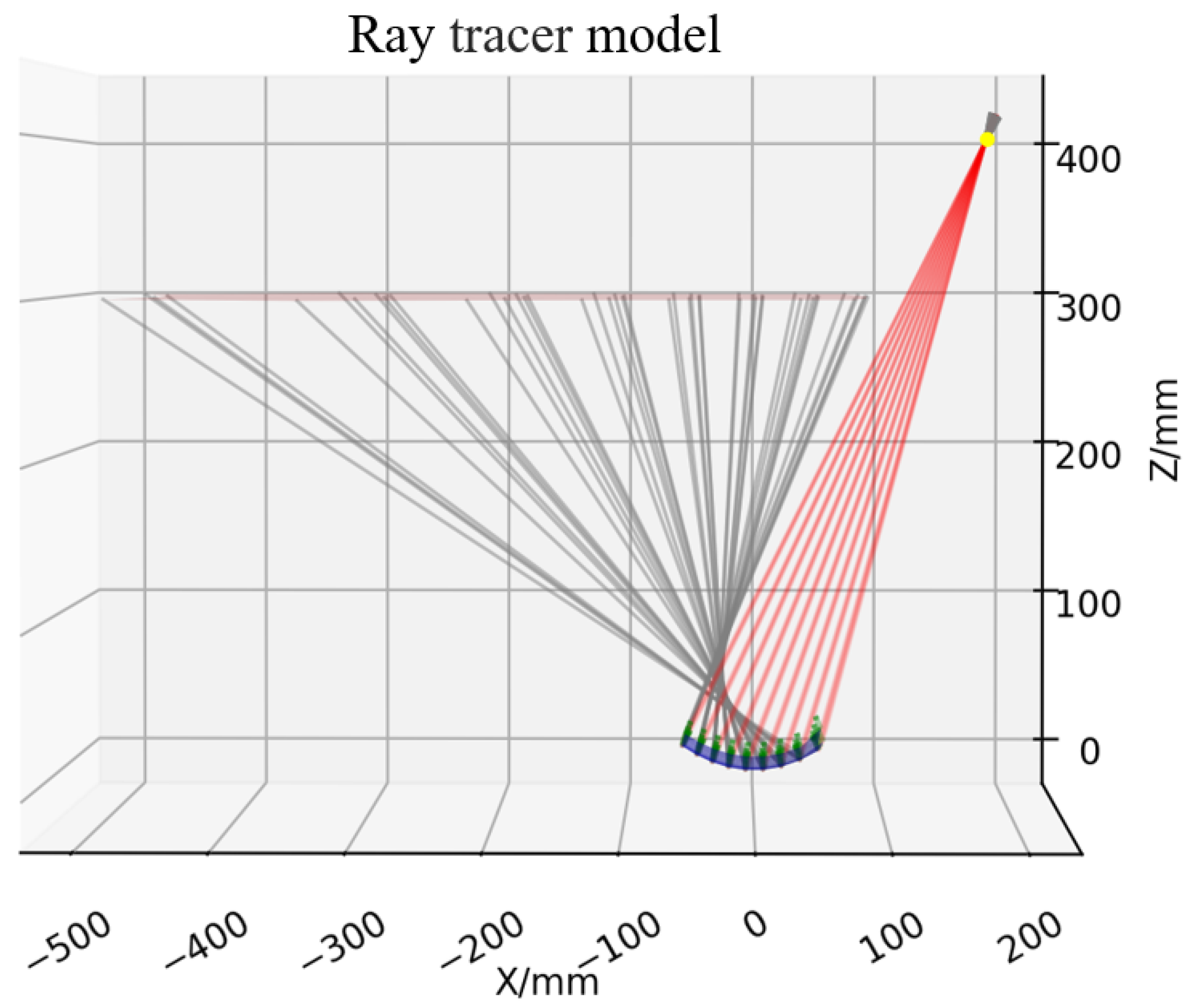

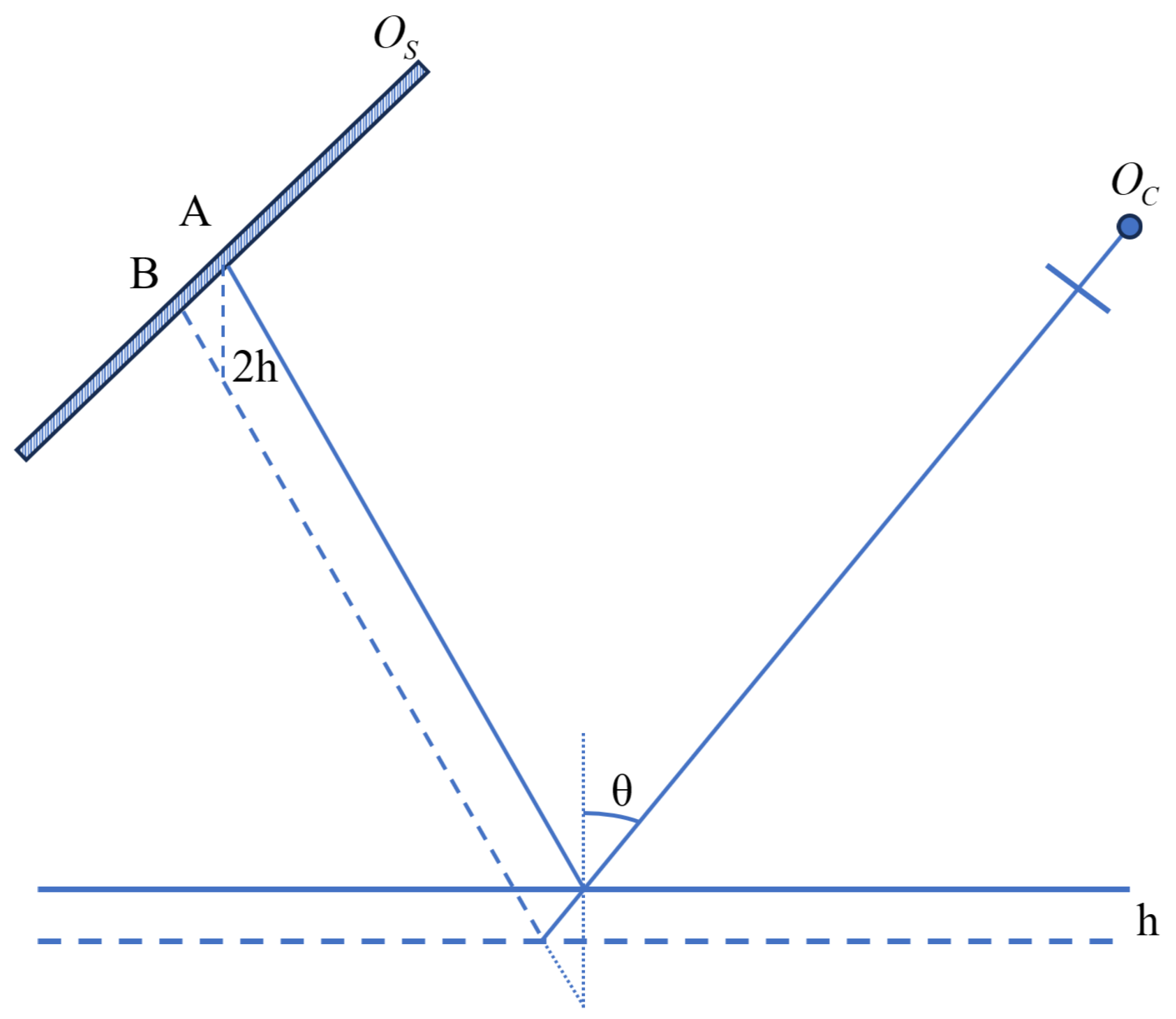

2. Principle

3. Global Optimization of Calibration

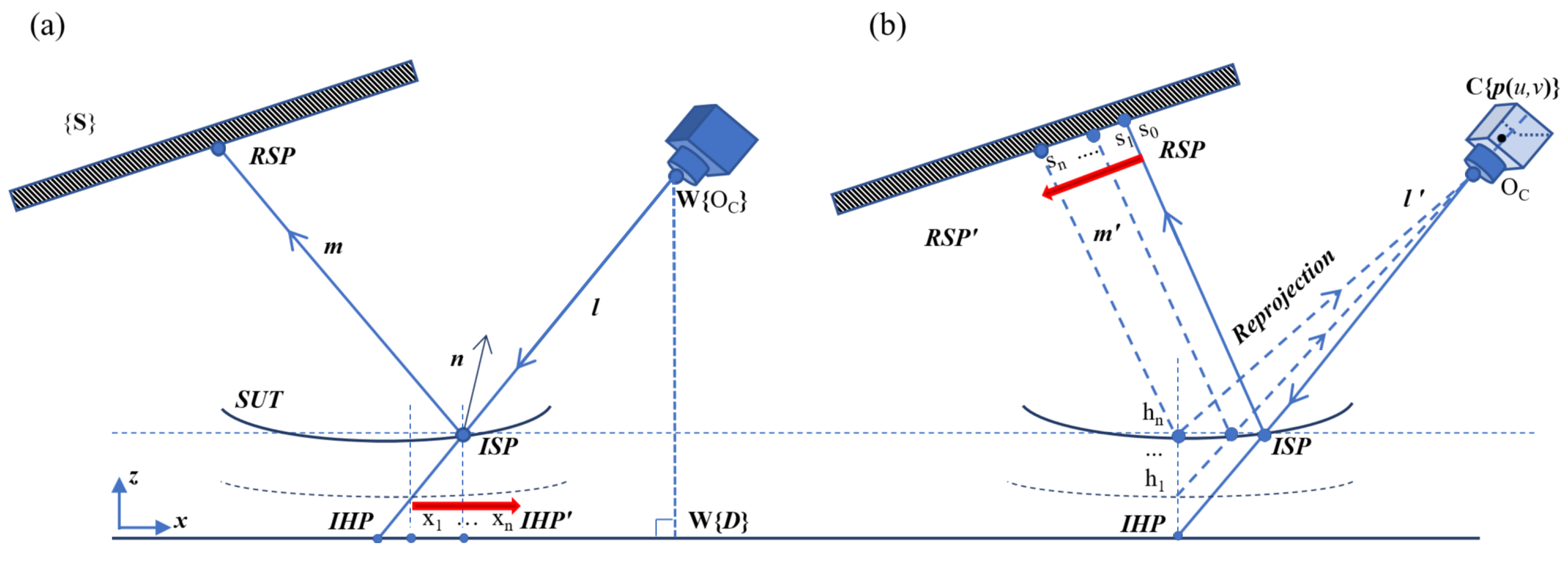

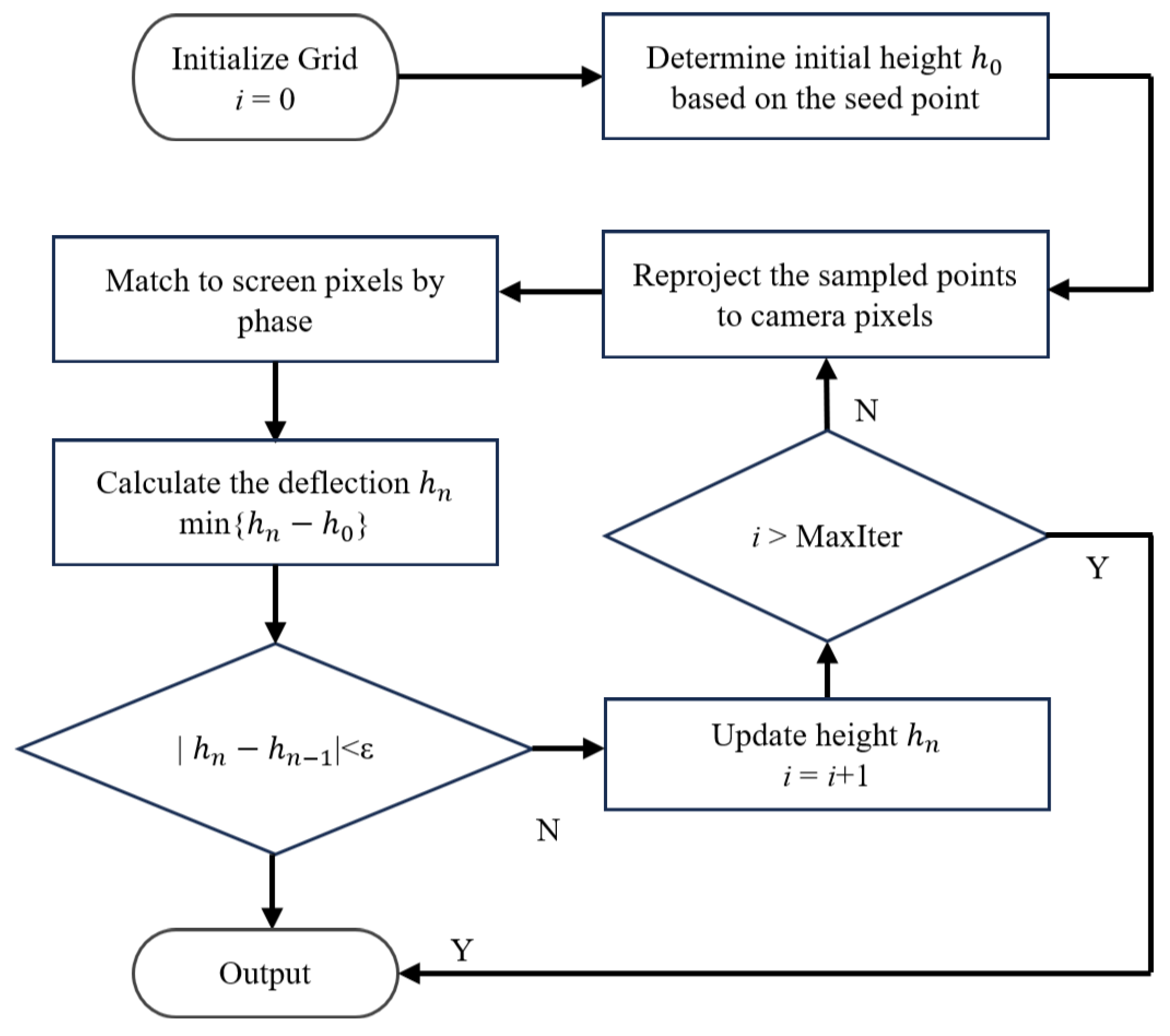

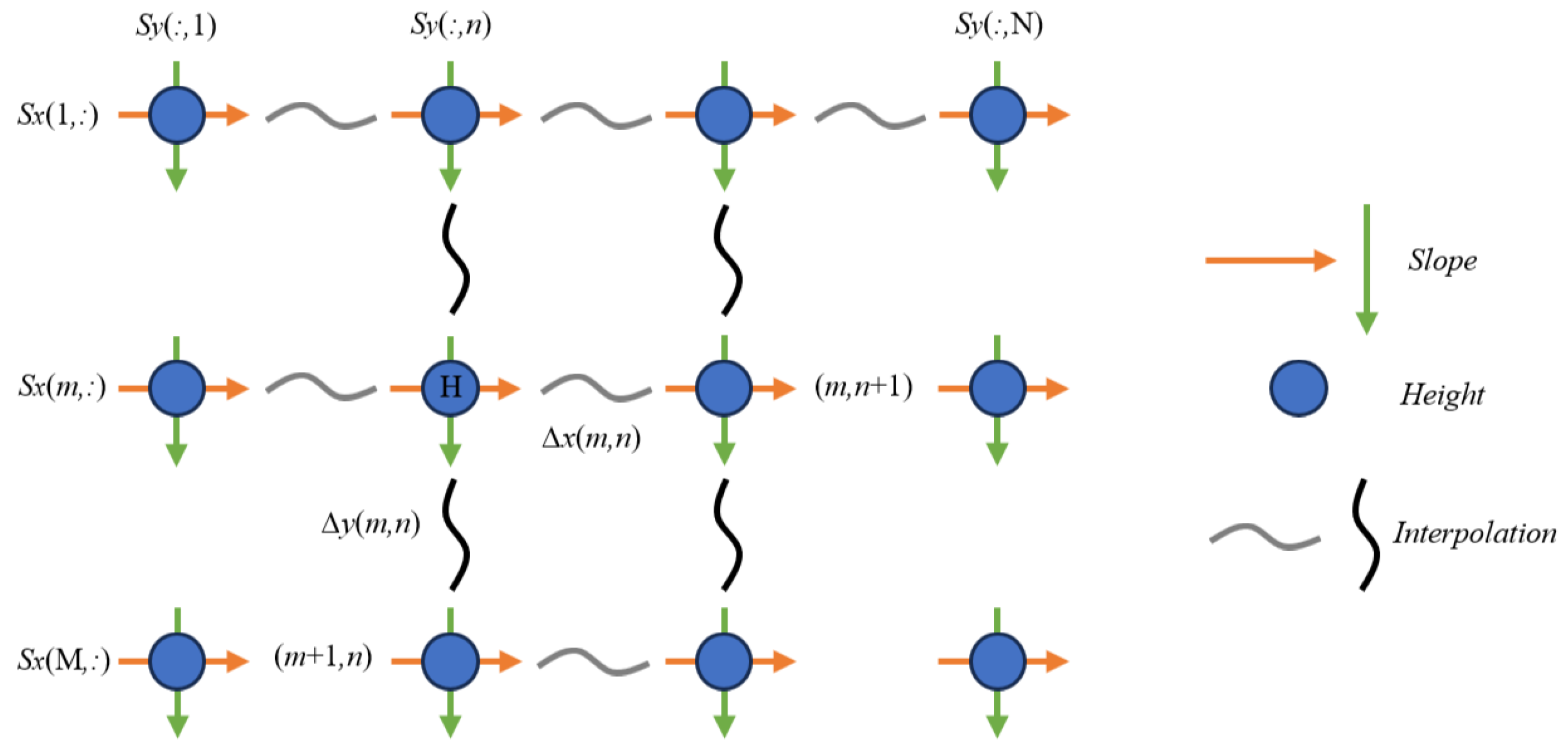

4. Iteration Strategies

4.1. OC and RC Strategies

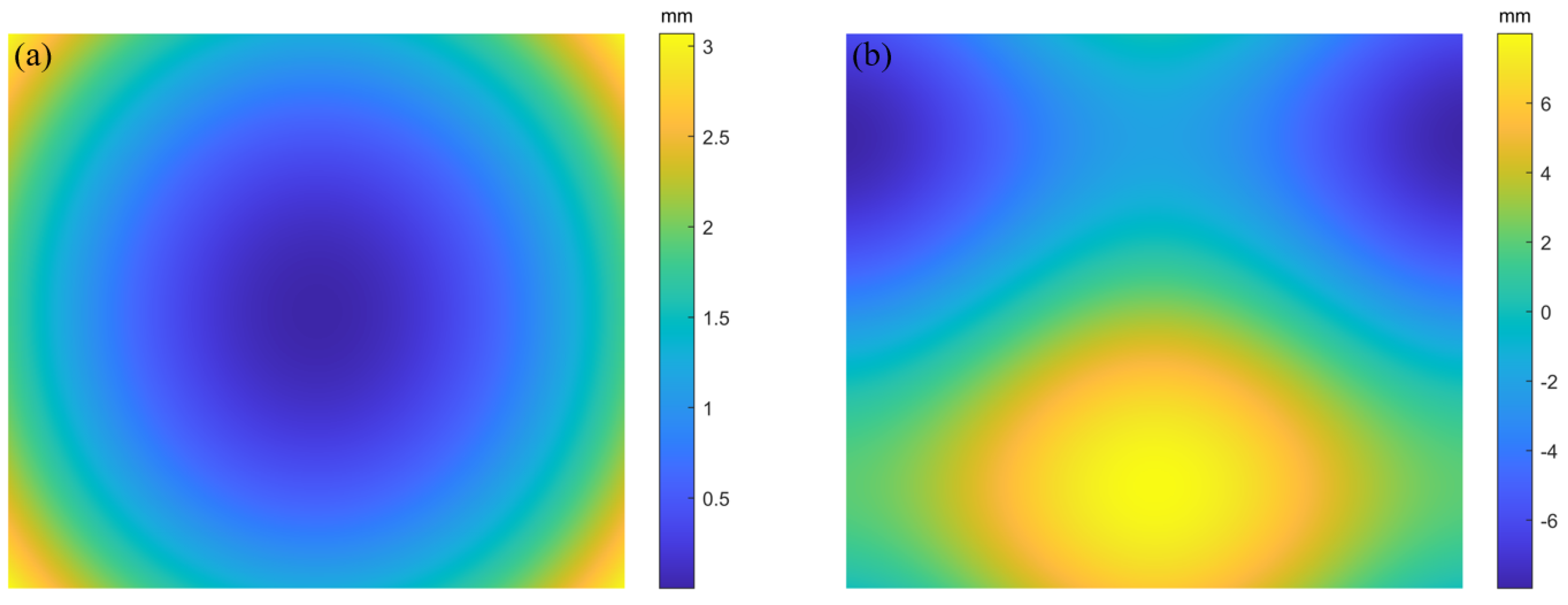

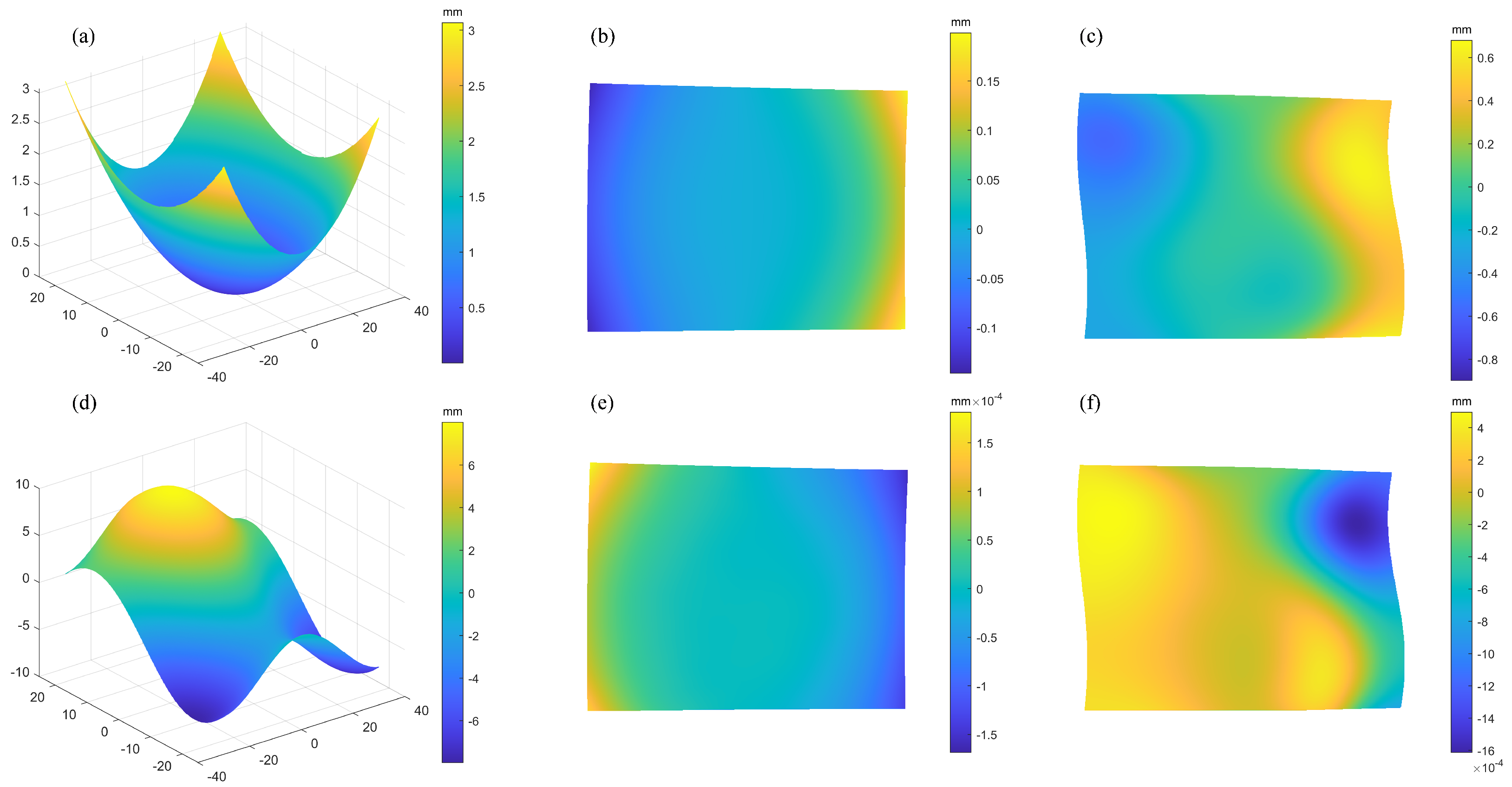

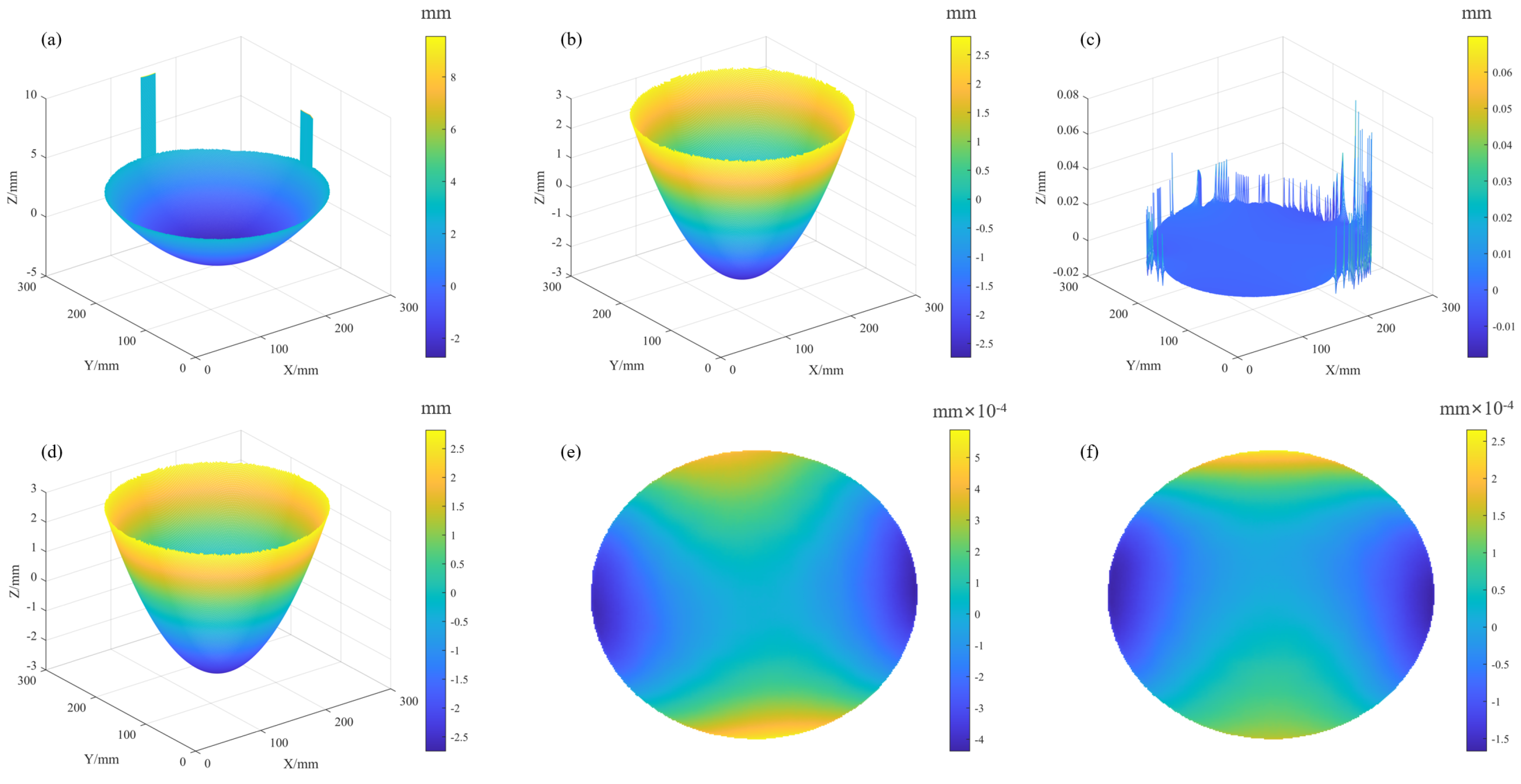

4.2. Simulation

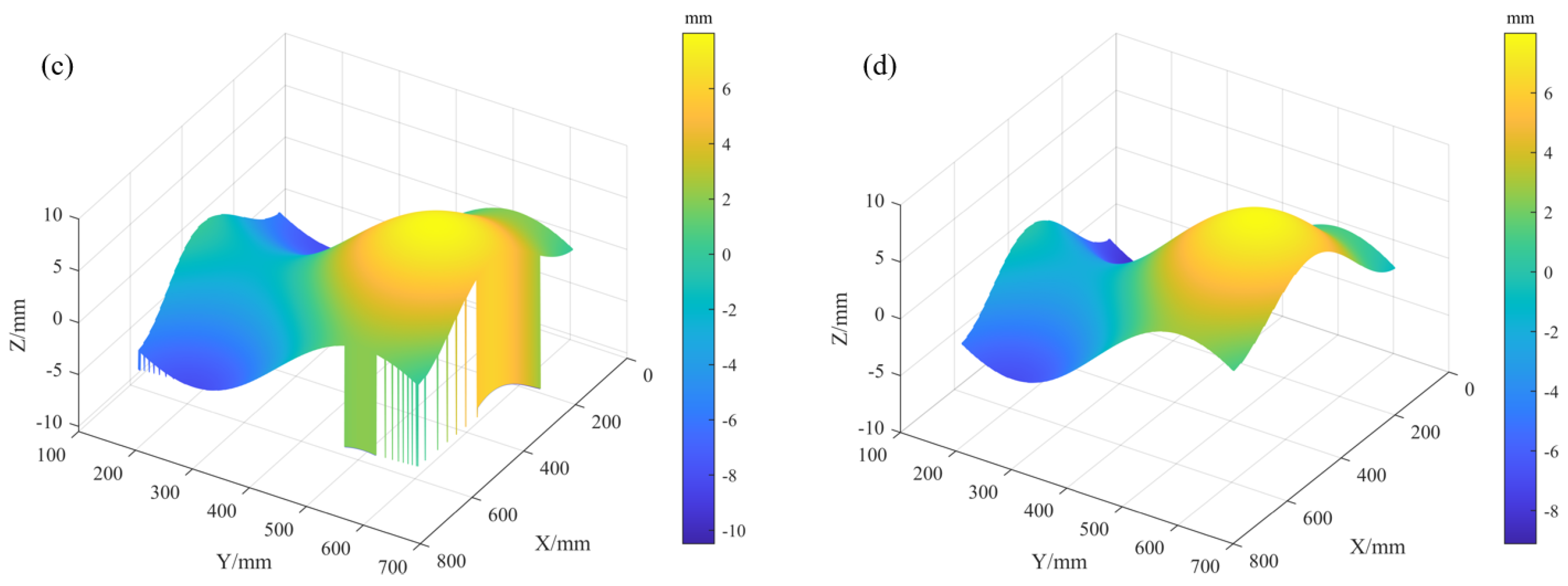

5. Edge Artifact Suppression

6. Experiment

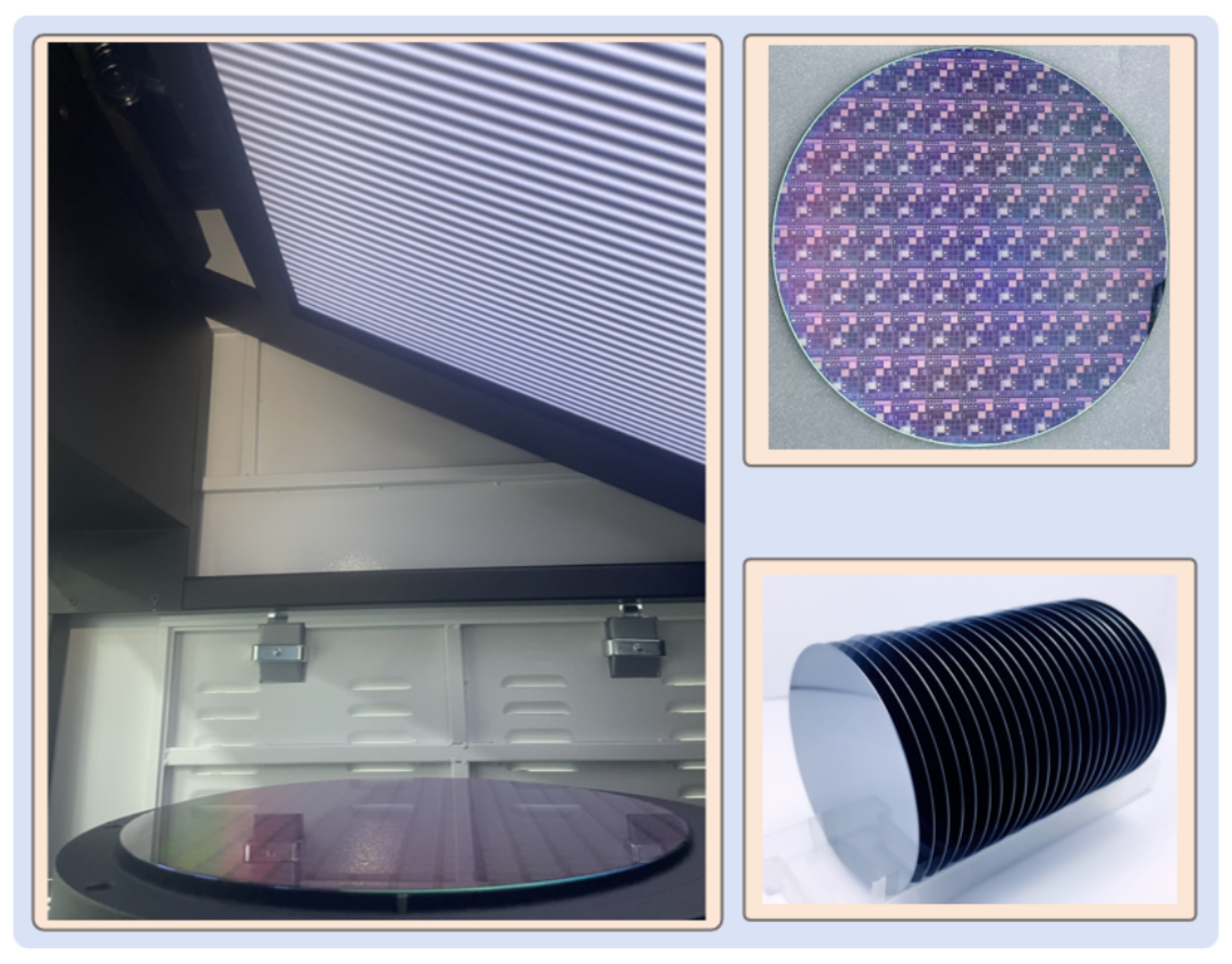

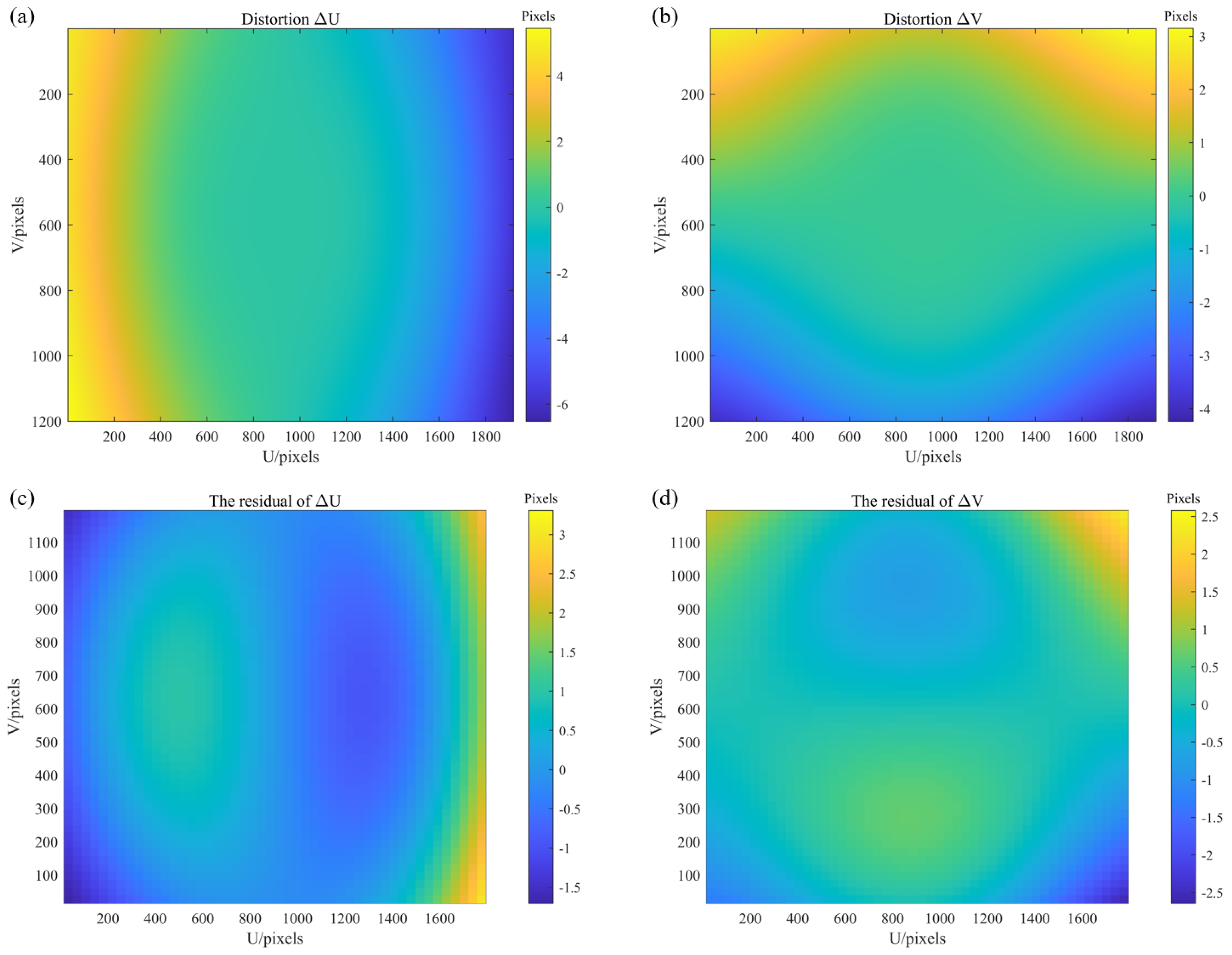

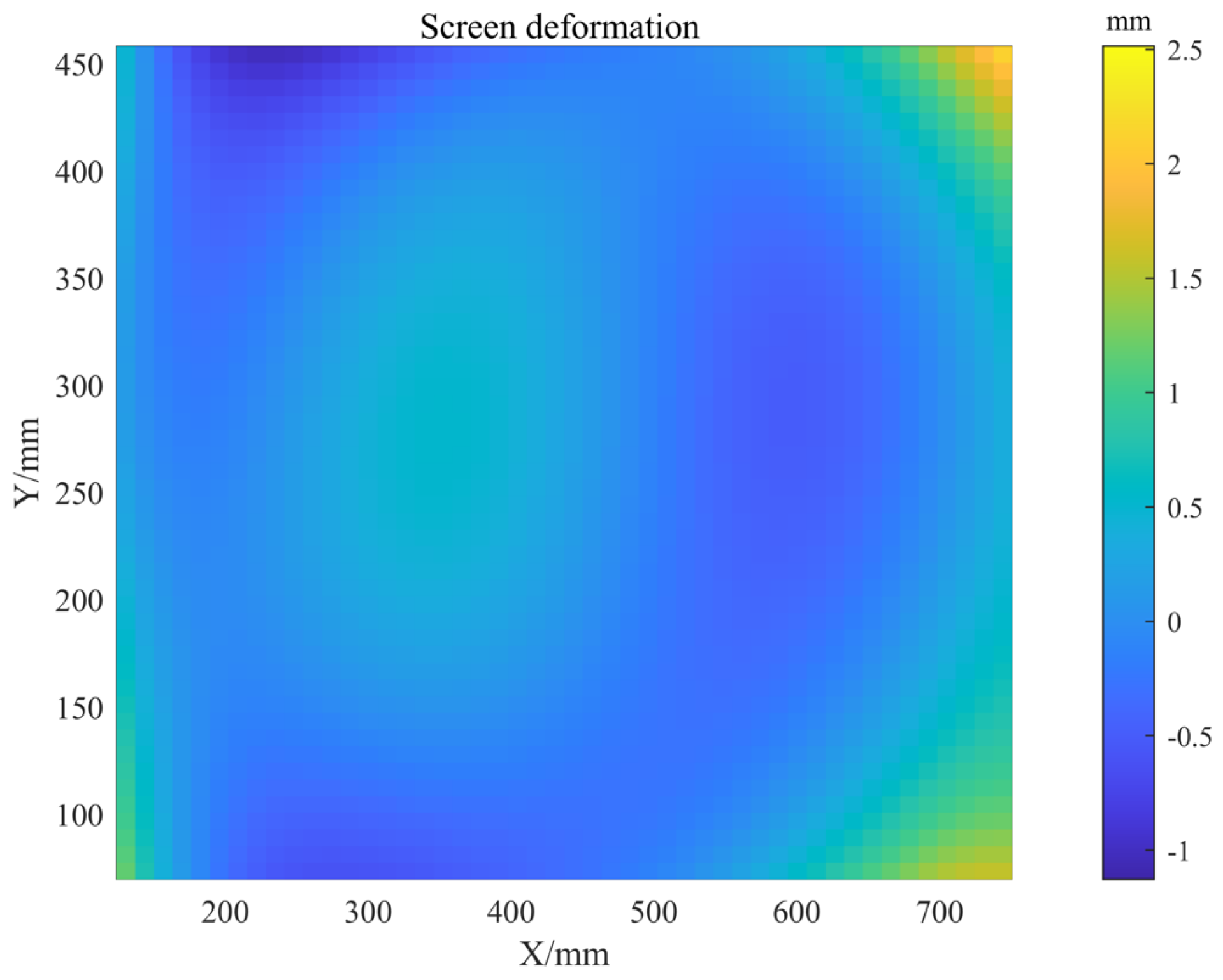

6.1. System Setup and Characterization

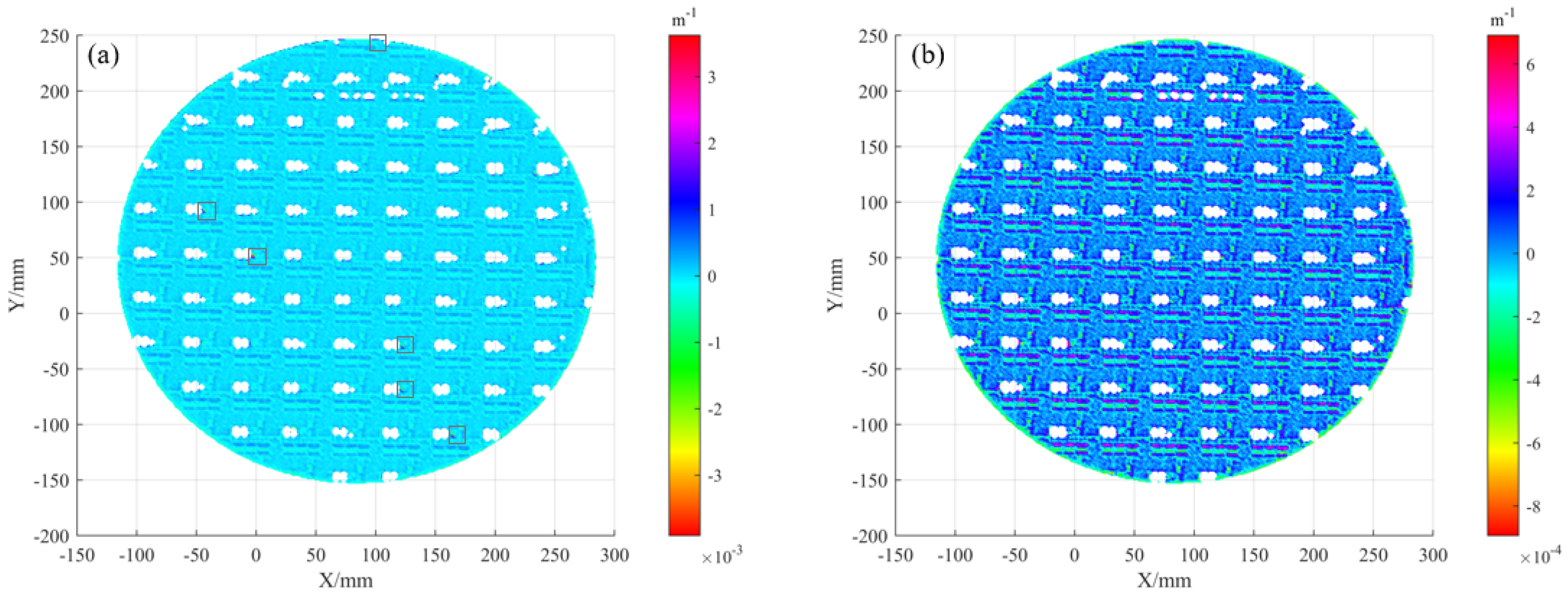

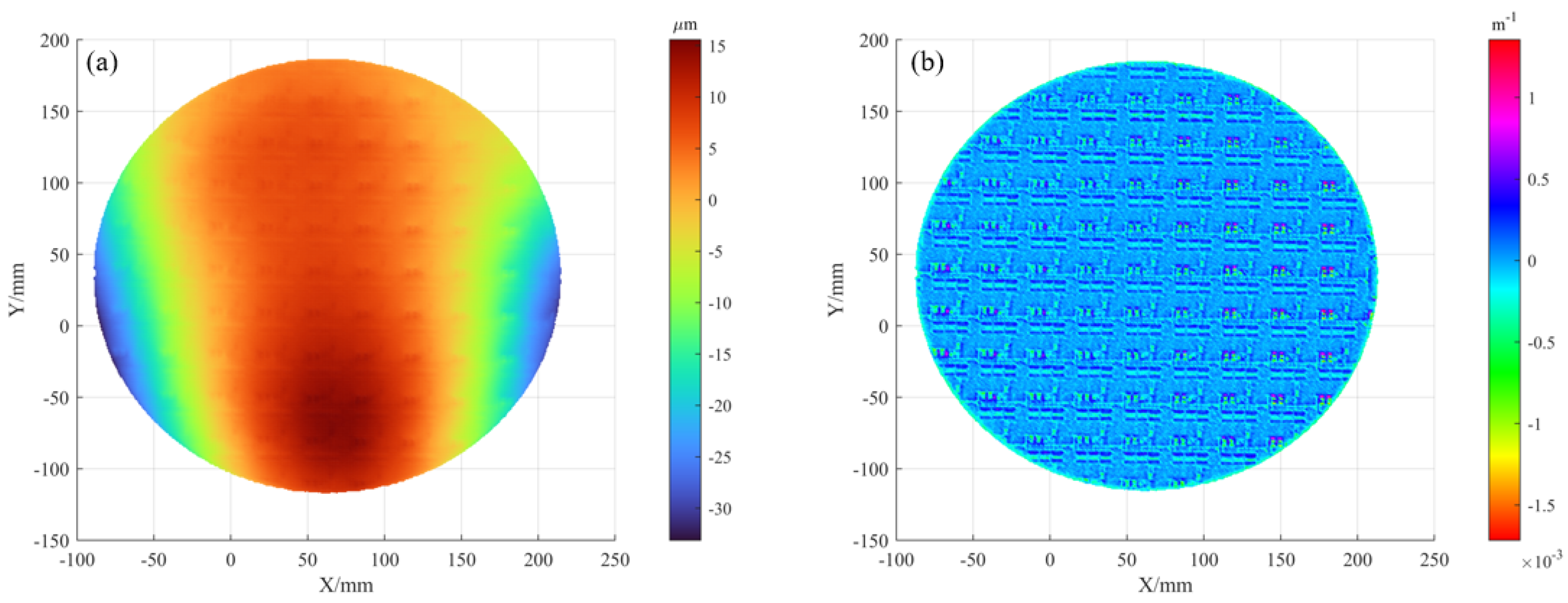

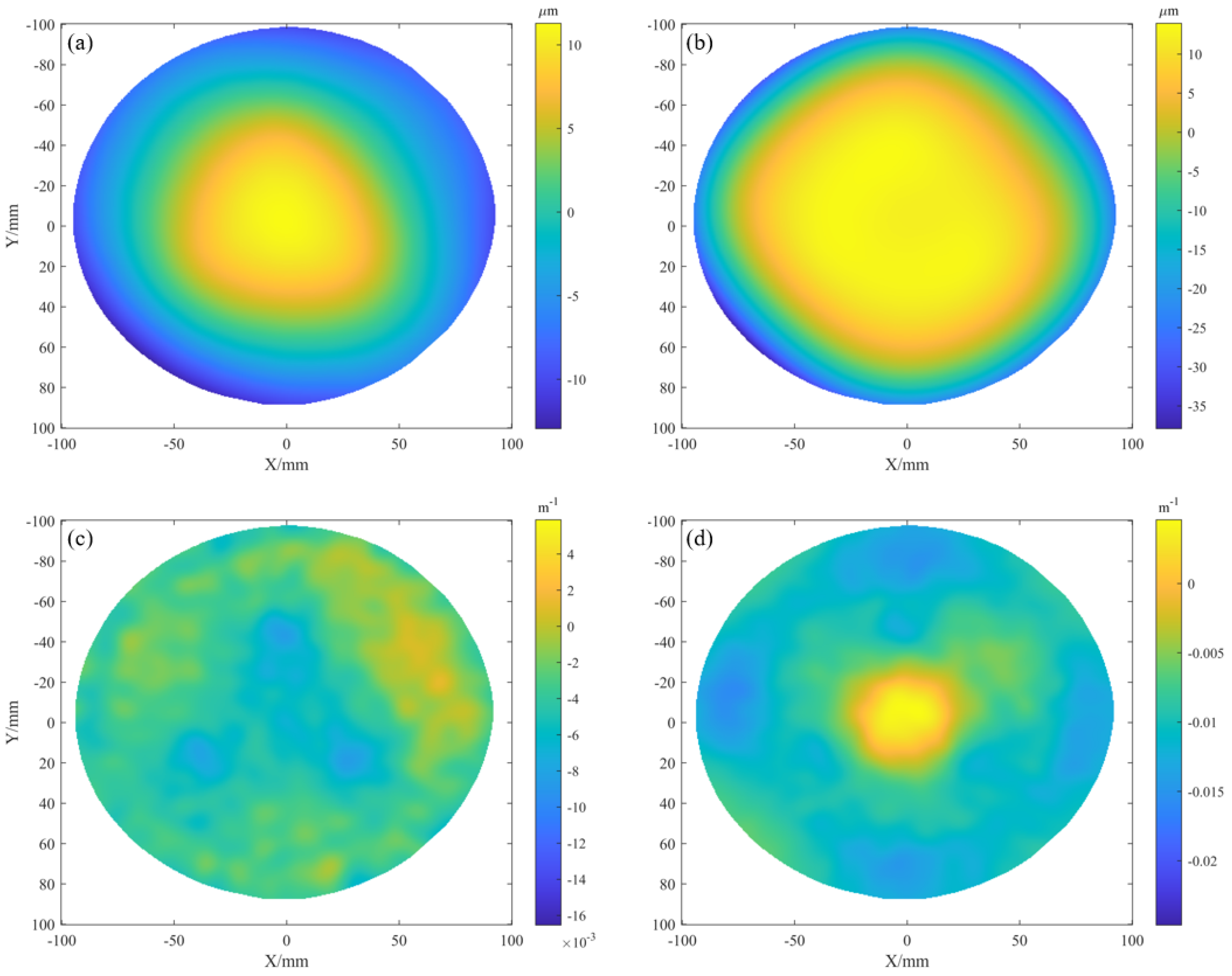

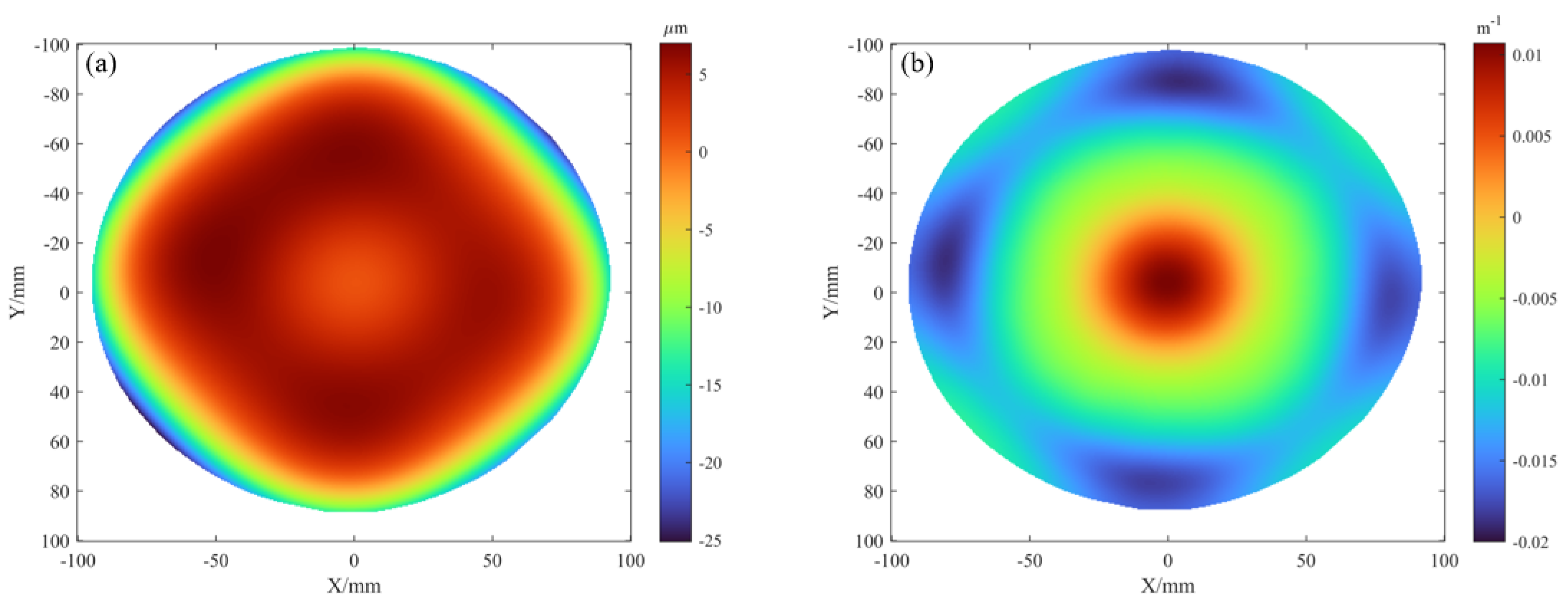

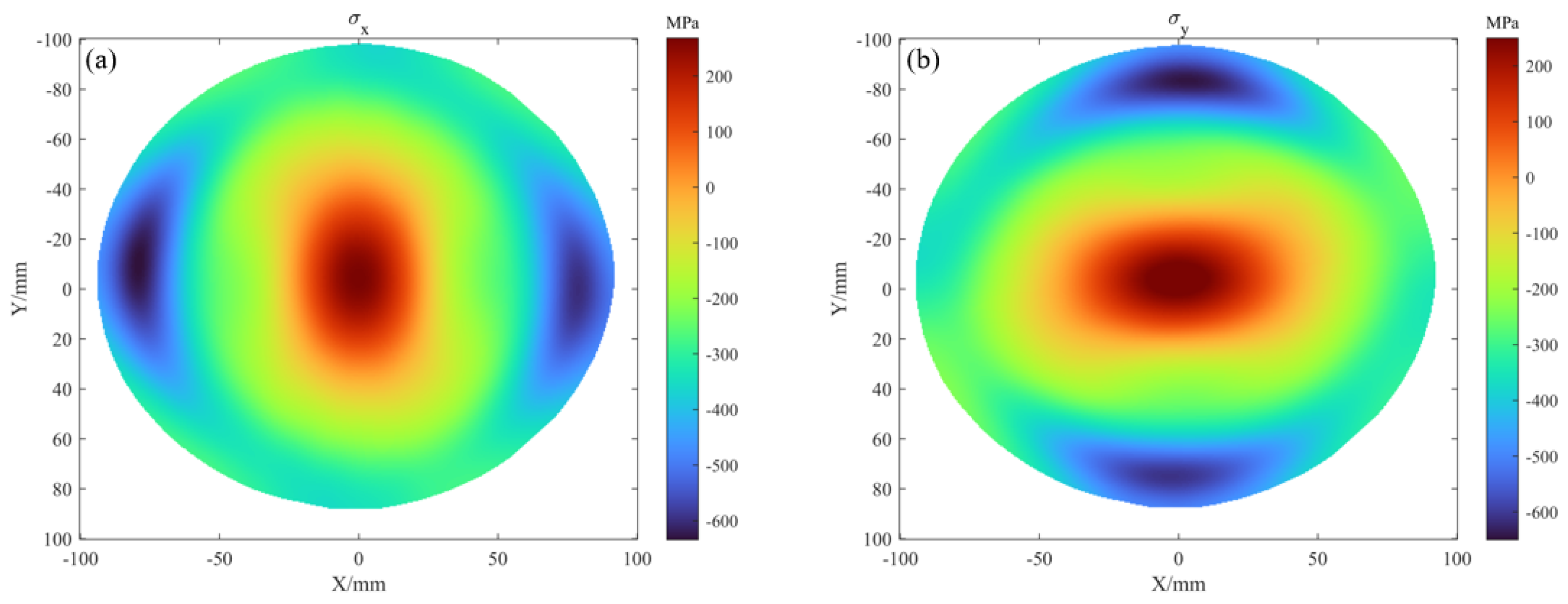

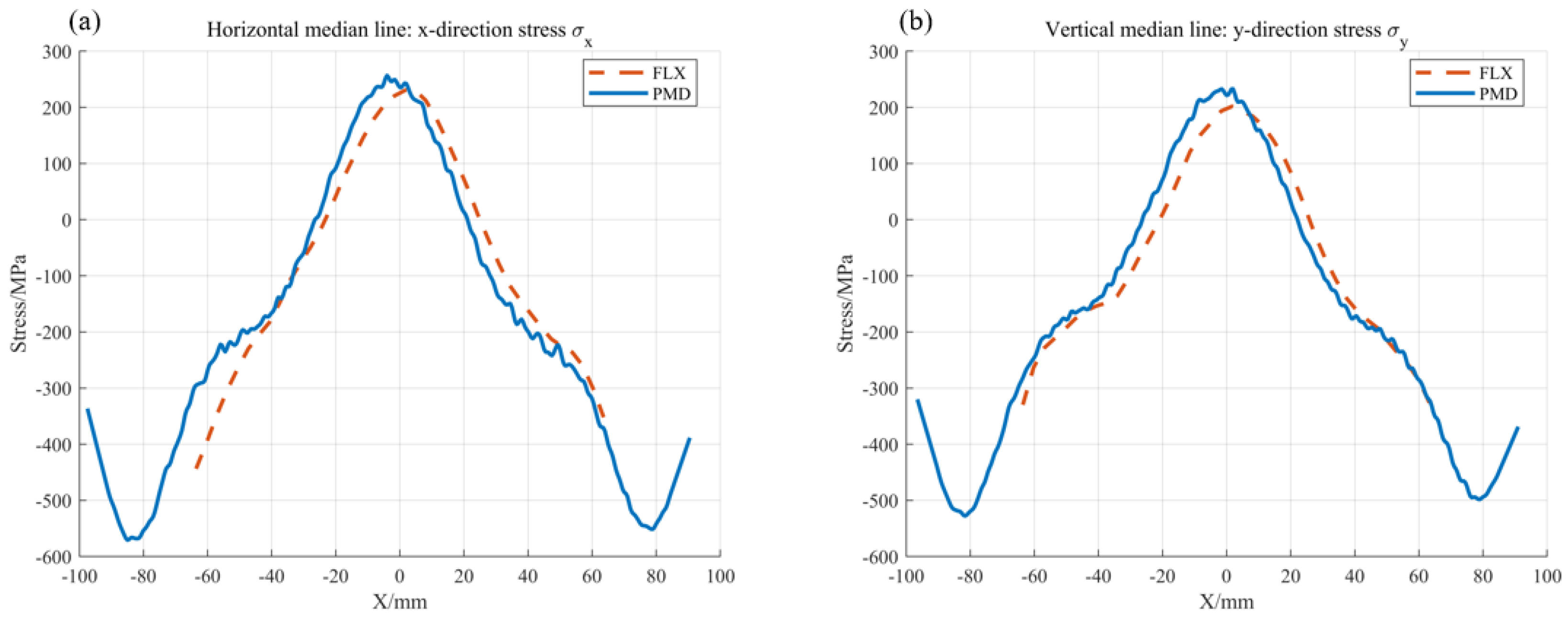

6.2. Validation on Patterned and Bare Wafers

6.3. Phase Error Analysis from Parasitic Reflections

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Camera Intrinsic Matrix

Appendix A.2. Camera Extrinsic Matrix

Appendix A.3. Mirror Deformation Parameters

References

- Kumar, S.; Zhong, W.; Williamson, J.; Kumar, P.; Furness, T.; Lou, S.; Zeng, W.; Jiang, X. Design, fabrication, and testing of freeform mirror-based head-up display system. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huke, P.; Burke, J.; von Kopylow, C.; Bergmann, R.B. Measuring deformations with deflectometry. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optical Engineering + Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2014; Interferometry XVII: Techniques and Analysis. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9203, pp. 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Krey, S.; van Amstel, W.D.; Szwedowicz, K.; Campos, J.; Moreno, A.; Lous, E.J. A fast optical scanning deflectometer for measuring the topography of large silicon wafers. In Proceedings of the Optical Science and Technology, the SPIE 49th Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 2–6 August 2004; Current Developments in Lens Design and Optical Engineering V. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5523, pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, M.L.; Gorji, N.E. Metrology of warpage in silicon wafers using X-ray diffraction mapping. IEEE Trans. Components Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 15, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esashi, M. Wafer level packaging of MEMS. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2008, 18, 073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praful, P.; Bailey, C. Warpage in wafer-level packaging: A review of causes, modelling, and mitigation strategies. Front. Electron. 2025, 5, 1515860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.H. Recent advances and trends in advanced packaging. IEEE Trans. Components Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 12, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarihan, V. Role of film intrinsic stress in packaging of multi-layer microelectronic structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 421, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Belhenini, S.; Roqueta, F.; Pujos, C.; Bruno, E.; Gardes, P.; Tougui, A. Intrinsic stress effects on the warpage of silicon substrate during thin film deposition, photolithography and etching processes. In Proceedings of the 2016 17th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), Montpellier, France, 18–20 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Lyu, P.; Wang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W. Polymer-Based wafer-Level Warpage Prediction and Regulation for the Advanced Packaging. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 19th International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS), Kyoto, Japan, 2–5 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Airaksinen, V.M. Silicon wafer and thin film measurements. In Handbook of Silicon Based MEMS Materials and Technologies; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, G.C.; Abdalla, M.M.; Van Keulen, F.; Pujada, B.R.; Van Venrooy, B. Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Stoney equation for film stress: Developments from polycrystalline steel strips to single crystal silicon wafers. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.M. Stress inspection for overlay characterization. In Proceedings of the SPIE Advanced Lithography, San Jose, CA, USA, 26–27 February 2013; Metrology, Inspection, and Process Control for Microlithography XXVII. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2013; Volume 8681, pp. 754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Chen, Y.; She, P.; Liu, C.; He, X.; Lv, S. Modeling the measurement precision of a multi-camera system. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 6489–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Feng, S.; Yin, W.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Trusiak, M.; Kujawinska, M.; Chen, Q.; et al. Dual-frequency angular-multiplexed fringe projection profilometry with deep learning: Breaking hardware limits for ultra-high-speed 3D imaging. Opto-Electron. Adv. 2025, 8, 250021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Powell, R.E.; Hanna, C.R.; Ume, I.C. Warpage measurement comparison using shadow moiré and projection moiré methods. IEEE Trans. Components Packag. Technol. 2002, 25, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Yan, K. A novel high-precision measurement method for warpage and bow of double-sided polished wafers based on wavelength-tunable laser interferometry. Measurement 2025, 258, 119124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häusler, G.; Faber, C.; Olesch, E.; Ettl, S. Deflectometry vs. interferometry. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optical Metrology 2013, Munich, Germany, 13–16 May 2013; Optical measurement systems for industrial inspection VIII. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2013; Voluem 8788, pp. 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, T.A.; Zhou, Y.; Wong, C.W.; Morgenfeld, B.; Leino, G.; Mahajan, S. Patterned wafer geometry (PWG) metrology for improving process-induced overlay and focus problems. In Proceedings of the SPIE Advanced Lithography, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–25 February 2016; Optical Microlithography XXIX. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 9780, pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, S.S.; Sharma, R.; Mukhiya, R. Experimental evaluation of stress in thin-films for MEMS applications. ISSS J. Micro Smart Syst. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Z.; Cai, W.; Chen, J.; Yao, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Lan, L.; et al. Effect of intrinsic stress on structural and optical properties of amorphous Si-doped SnO2 thin-film. Materials 2017, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauer, M.C.; Kaminski, J.; Hausler, G. Phase measuring deflectometry: A new approach to measure specular free-form surfaces. In Proceedings of the Photonics Europe, Strasbourg, France, 27–30 April 2004; Optical Metrology in Production Engineering. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Voume 5457, pp. 366–376. [Google Scholar]

- Arnal, L.; Solanes, J.E.; Molina, J.; Tornero, J. Detecting dings and dents on specular car body surfaces based on optical flow. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 45, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geckeler, R.D.; Weingaertner, I. Sub-nm topography measurement by deflectometry: Flatness standard and wafer nanotopography. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Optical Science and Technology, Seattle, WA, USA, 7–11 July 2002; Advanced Characterization Techniques for Optical, Semiconductor, and Data Storage Components. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2002; Volume 4779, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Yang, P.D.; Zhang, X.C.; Lang, W.; Chen, Y.N.; Xu, M. Separation of fringe patterns in fast deflectometric measurement of transparent optical elements based on neural network-assisted fast iterative filtering method. Adv. Manuf. 2025, 13, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Gao, F.; Jiang, X. Iterative optimization calibration method for stereo deflectometry. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 22060–22068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. A flexible new technique for camera calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geckeler, R.D.; Just, A. Optimized use and calibration of autocollimators in deflectometry. In Proceedings of the Optical Engineering + Applications, 2007, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–30 August 2007; Advances in Metrology for X-ray and EUV Optics II. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; Volume 6704, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Jiang, X. Holistic calibration method of deflectometry by holonomic framework priors. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Wu, S.; Song, Z. An accurate calibration means for the phase measuring deflectometry system. Sensors 2019, 19, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, M. In-situ deflectometic measurement of transparent optics in precision robotic polishing. Precis. Eng. 2020, 64, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Nobuhara, S.; Matsuyama, T. A new mirror-based extrinsic camera calibration using an orthogonality constraint. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1051–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.L.; Su, X.; Chen, W. Flexible geometrical calibration for fringe-reflection 3D measurement. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. 3D global optimization of calibration parameters of deflectometry system by using a spherical mirror. Measurement 2023, 219, 113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, X. A holistic calibration method with iterative distortion compensation for stereo deflectometry. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 106, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Xing, Y.; Ao, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C. Vision-Ray-Calibration-Based Monocular Deflectometry by Poses Estimation from Reflections. Sensors 2025, 25, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, D.; Zheng, W.; Yu, L.; Ge, R.; Zhang, X. Vision ray model based stereo deflectometry for the measurement of the specular surface. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 172, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, F.; Jiang, X. Performance analysis and evaluation of geometric parameters in stereo deflectometry. Engineering 2018, 4, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Jiang, X. Performance analysis and evaluation of direct phase measuring deflectometry. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 103, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cossairt, O.; Willomitzer, F. 3D imaging of complex specular surfaces by fusing polarimetric and deflectometric information. Optica 2025, 12, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Li, B.; Wei, X.; Zappa, E. Iterative reconstruction method with auto-updated seed point of monoscopic deflectometry for off-axis aspheric. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wu, S.; Song, Z.; Gu, F.; Zhao, J. 3D reconstruction of the specular surface using an iterative stereoscopic deflectometry method. Optics Express 2021, 29, 12867–12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.M. Modal wave-front reconstruction with Zernike polynomials and Karhunen–Loève functions. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1996, 13, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Idir, M.; Zuo, C.; Kaznatcheev, K.; Zhou, L.; Asundi, A. Comparison of two-dimensional integration methods for shape reconstruction from gradient data. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2015, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, F. A robust iterative reconstruction technique for deflectometry. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2025, 8, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Parks, R.E.; Wang, L.; Angel, R.P.; Burge, J.H. Software configurable optical test system: A computerized reverse Hartmann test. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 4404–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrulle, A.A. Householder transformations revisited. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2000, 22, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xue, J.; Gao, B.; Zuo, C.; Idir, M. Zonal wavefront reconstruction in quadrilateral geometry for phase measuring deflectometry. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 5139–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xue, J.; Gao, B.; Zuo, C.; Idir, M. Spline based least squares integration for two-dimensional shape or wavefront reconstruction. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017, 91, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazopoulos, K.A.; Lazopoulos, A.K. Fractional differential geometry of curves & surfaces. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2016, 2, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Tzeng, P.; Lee, C.; Zhan, C.; Li, M.; Cline, J.; Saito, K.; Hsin, Y.; Chang, P.; Chang, Y.; et al. Redistribution layers (RDLs) for 2.5 D/3D IC integration. J. Microelectron. Electron. Packag. 2014, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Yue, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, T.; Cai, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y. Elimination of parasitic reflections for objects with high transparency in phase measuring deflectometry. Results Phys. 2019, 15, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Round | Spherical-RC | Spherical-OC | Free-Form-RC | Free-Form-OC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 373.1 | 344.8 | 2206.7 | 1579.3 |

| 2 | 8.04 | 9.1 | 310.8 | 366.5 |

| 3 | 0.1 | 0.49 | 6.72 | 7.24 |

| 4 | 0.0916 | 0.35 | 0.2627 | 2.09 |

| 5 | 0.0915 | 0.348 | 0.2626 | 2.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Wan, X.; Hsin, K.; Tao, J.; Yin, Z.; Yang, F. Phase Measuring Deflectometry for Wafer Thin-Film Stress Mapping. Sensors 2025, 25, 7668. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247668

Gao Y, Wan X, Hsin K, Tao J, Yin Z, Yang F. Phase Measuring Deflectometry for Wafer Thin-Film Stress Mapping. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7668. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247668

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yang, Xinjun Wan, Kunying Hsin, Jiaqing Tao, Zhuoyi Yin, and Fujun Yang. 2025. "Phase Measuring Deflectometry for Wafer Thin-Film Stress Mapping" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7668. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247668

APA StyleGao, Y., Wan, X., Hsin, K., Tao, J., Yin, Z., & Yang, F. (2025). Phase Measuring Deflectometry for Wafer Thin-Film Stress Mapping. Sensors, 25(24), 7668. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247668