Synthesizing the overall trends across the tested crash pulses reveals a distinct evolution in the dummy’s biomechanical response. At low-energy pulses (10 g), the primary deviation is observed in amplitude effects, where the compliance of the overlays actively dampens peak accelerations. As the energy increases to medium pulses (15 g), the system exhibits high timing sensitivity; this is the transitional phase where phase shifts are most pronounced due to the variable stabilization time of the foam. Finally, at high-energy pulses (20 g), the response shifts towards controlled deformation behavior. Under these loads, the material is fully compressed, resulting in a synchronization of waveforms and minimizing time delays, as the biomechanical response becomes dominated by the structural stiffness of the overlays rather than the initial compliance of the overlay.

3.1. Peak Analysis

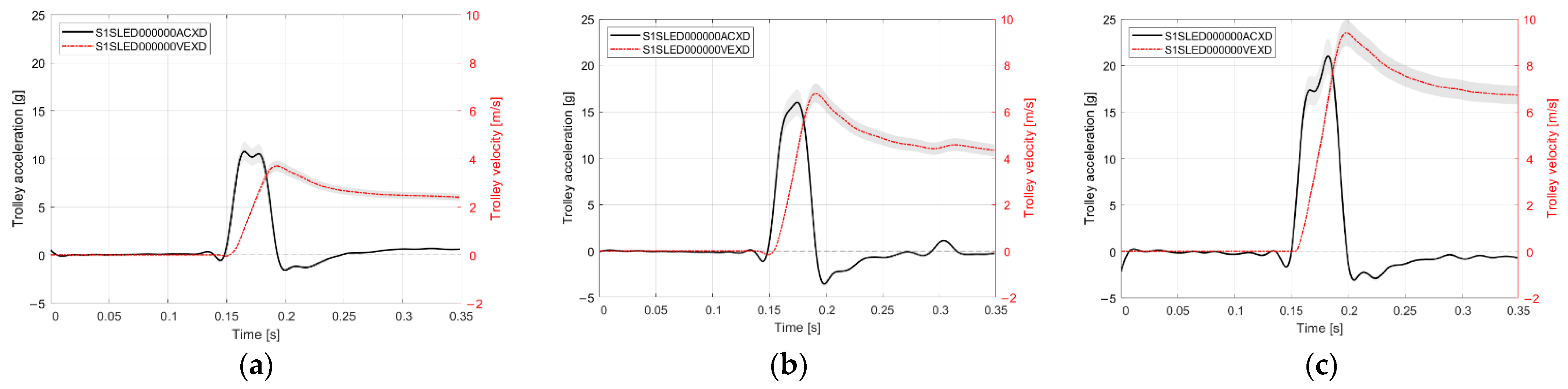

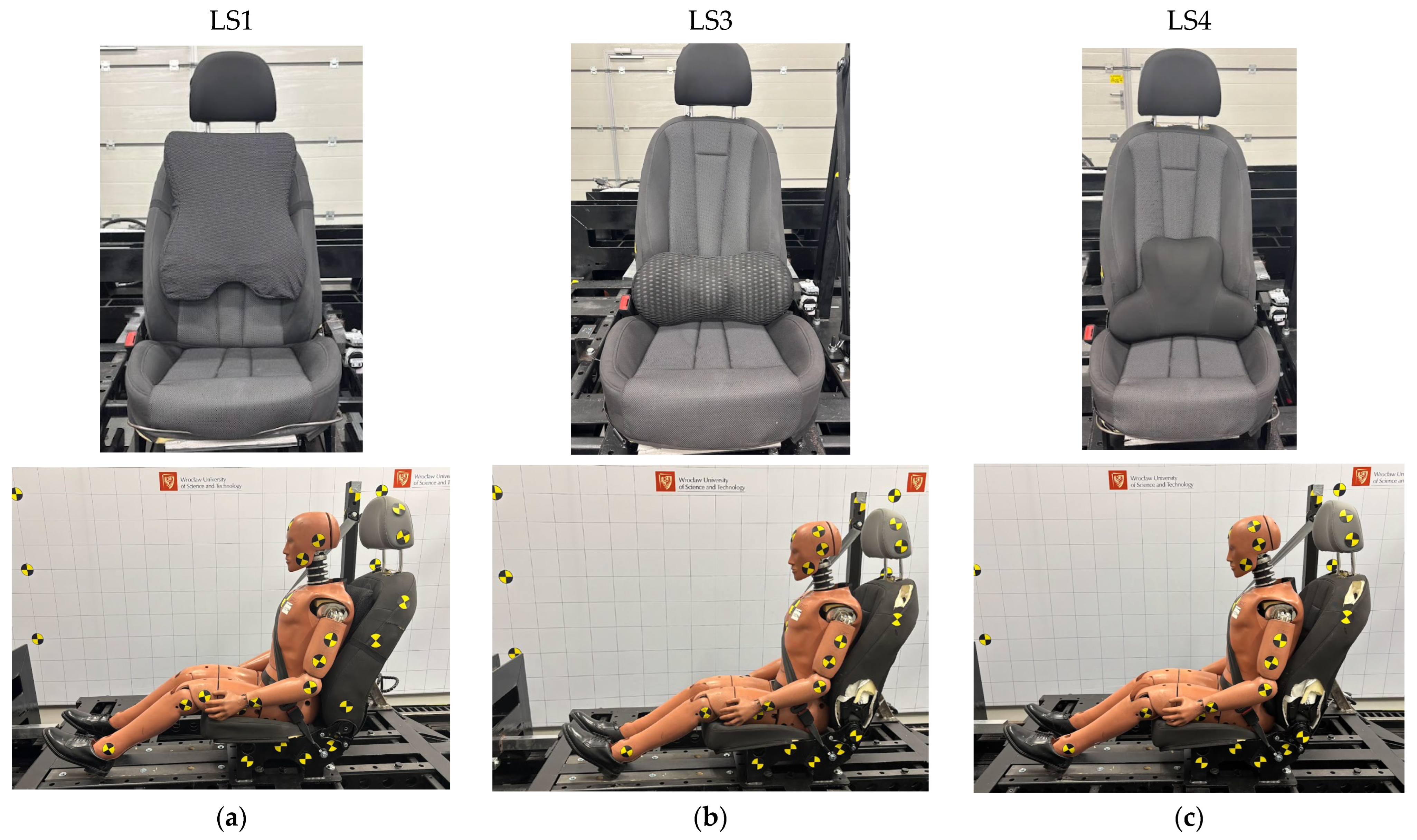

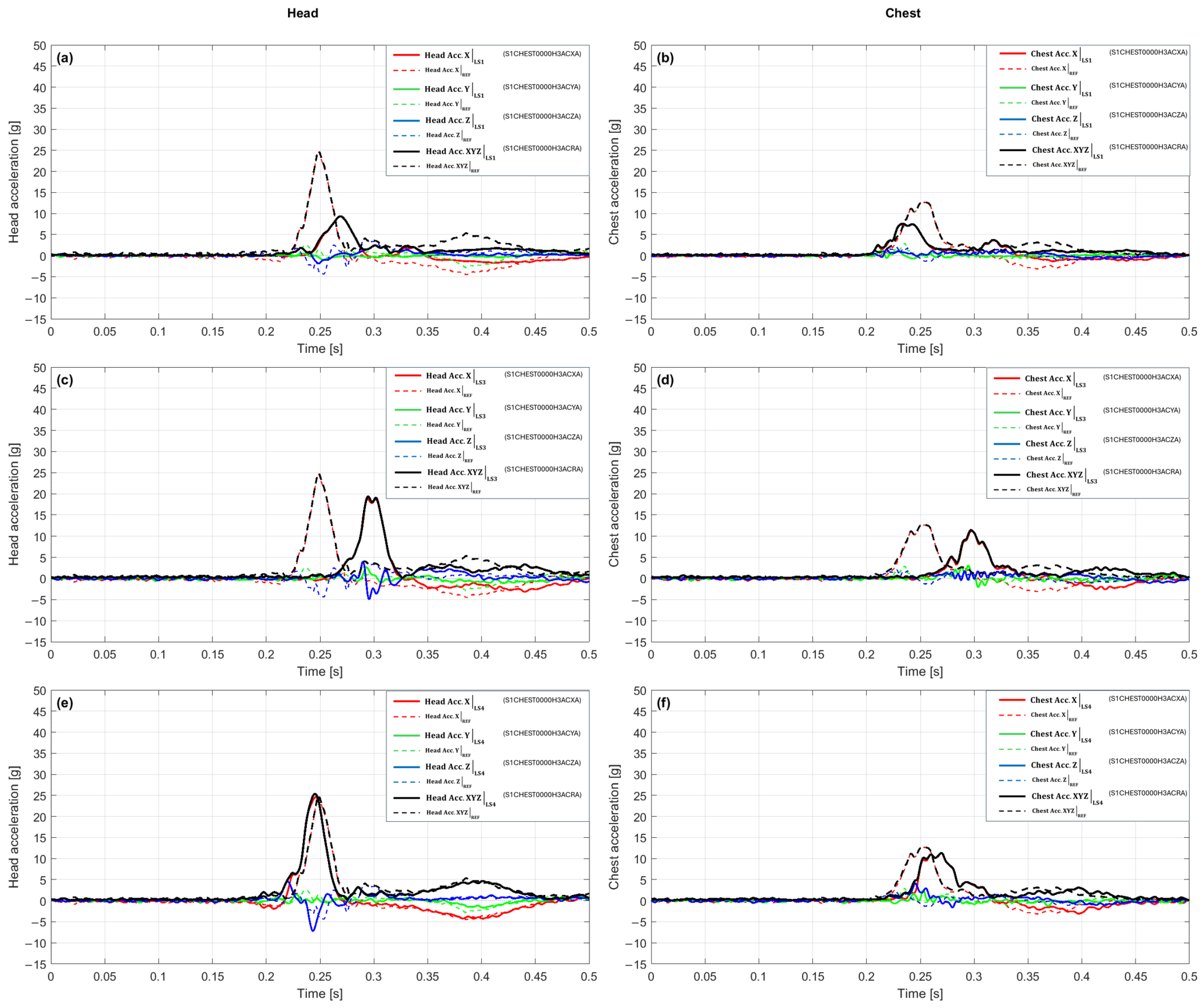

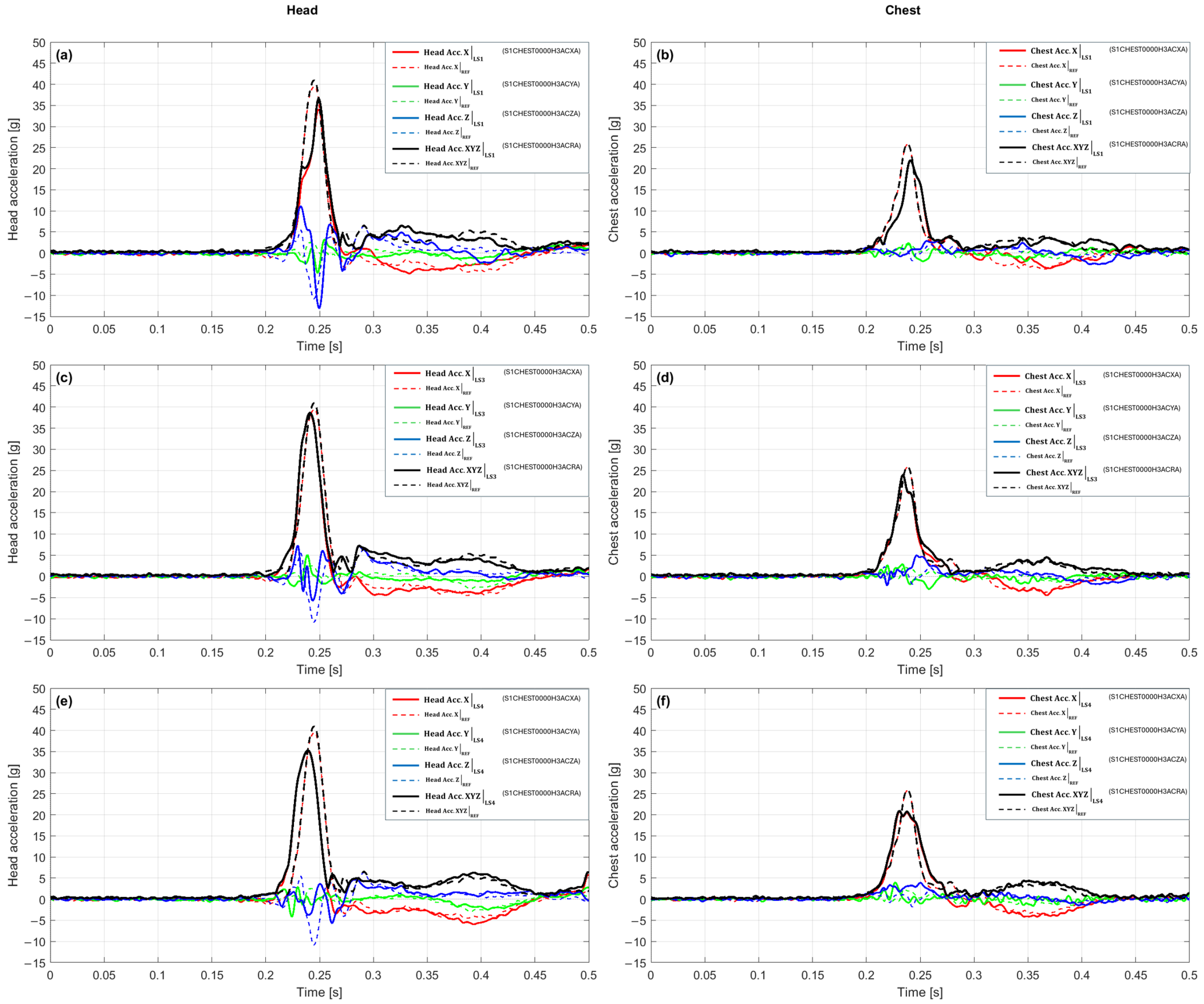

In the scenario with a 10 g crash pulse, waveforms from the LS1 variant were compared with the reference configuration (REF), referencing

Figure 4a,b. In the head (

Figure 4a) the first maximum in the reference configuration was 24.88 g at 0.249 s, while the LS1 variant recorded 9.34 g at 0.269 s. This signifies an amplitude reduction of 62.5% and a delay in the time of maximum of 0.020 s. The plot shows that the culmination for LS1 appears later and is distinctly lower; the signal rise to the peak is slower than in the reference configuration, and a gentler decay is observed after the culmination. The peak value remains dominated by the

X-axis component, while the Y and Z components do not reach comparable values at the same moment, which limits the resultant acceleration magnitude. Such a waveform indicates that in the head, the action of LS1 translates into a reduction in the peak load and an extension of the time to maximum, resulting in a slower and milder dynamic response.

In the chest (

Figure 4b) the first maximum in the reference configuration was 12.71 g at 0.254 s, while the LS1 variant achieved 7.55 g at 0.234 s. This corresponds to an amplitude drop of 40.6% and an acceleration of the time of maximum of 0.020 s. The plot shows that the peaks for LS1 appear earlier and at a lower level, suggesting a faster yet less intense response. Similarly to the head, the acceleration culmination coincides with the maximum of the X-component, whereas the lack of co-occurring extremes in the Y and Z axes limits the resultant value. Consequently, the action of LS1 in the chest leads to a significant dampening of the amplitude and a shortening of the response rise time relative to the reference configuration. The plot shows that the peaks for LS1 appear slightly earlier and at a lower level, indicating a faster but less intense dynamic response buildup. Similarly to the head, the acceleration culmination remains dominated by the X-component, whereas the lack of co-occurring extremes in the Y and Z axes limits the total resultant value. Consequently, the action of LS1 in the chest leads to a significant dampening of the amplitude and a shortening of the response rise time relative to the reference configuration.

Figure 4c,d presents a comparison of the dynamic responses for the LS3 variant and the reference configuration. In the head (

Figure 4c), a clear waveform phase shift is visible, where in the reference system the maximum is reached earlier (24.88 g at 0.249 s), while in the LS3 variant the peak only appears after 0.297 s, with a smaller amplitude of 19.37 g. This difference corresponds to a decrease of about 22% and indicates that the action of LS3 results in a slowing down and weakening of the head system’s response. In contrast to the reference waveform, where the acceleration rises sharply, the LS3 signal increases gradually, and the culmination is less distinct. The acceleration maximum is primarily associated with the dominant

X-axis component, while the Y and Z components remain relatively low at that moment, which limits the resultant value. Overall, the LS3 waveform features a milder time profile, more distributed in the rising phase, suggesting that the system reacts more slowly but with a lower peak load.

Figure 4d shows a clear difference in the acceleration waveforms of the chest between the reference configuration and the LS3 variant. In the case of the reference system, the maximum reaches 12.71 g at 0.254 s, whereas in the LS3 configuration, the peak shifts to 0.297 s and reaches 11.47 g. This signifies an amplitude reduction of 9.8%, combined with a distinct delay in the moment of culmination by 0.043 s. The shape of the LS3 curve suggests that the chest response develops more slowly, and the signal rises over a longer time interval, while reaching the maximum value is preceded by a phase of gentle increase. After the culmination, no sudden drop is observed, but a smooth dampening of the acceleration, which indicates a more temporally distributed system response. Compared to the reference configuration, the behavior of LS3 can be described as less dynamic but more controlled, with limited acceleration jumps and an extended reaction time to the crash pulse.

Figure 4e,f presents the acceleration waveforms for the LS4 variant compared to the reference configuration. In the case of the head (

Figure 4e), the first maximum in the reference configuration was 24.88 g at 0.249 s, whereas in the LS4 variant, 25.34 g was recorded at 0.245 s. This corresponds to a slight amplitude difference (an increase of 1.8%) and an acceleration of the moment of maximum by 0.004 s. The shape of the LS4 waveform remains very close to the reference one, and the rising phase is almost identical; however, the culmination occurs slightly earlier and at a minimally higher peak value. After reaching the maximum, the LS4 curve drops faster, which indicates a shorter duration of the intensive reaction phase. At the moment of culmination, the

X-axis component has the main contribution to the total value, while the remaining axes do not additionally amplify the signal, which limits further increase in the acceleration value.

Figure 4f shows a large convergence of the acceleration waveforms for the LS4 variant and the reference configuration, although subtle differences in the reaction dynamics are noticeable. In the chest, the maximum acceleration in LS4 is 11.32 g at 0.270 s, while in the reference configuration, it reached 12.71 g at 0.254 s. This signifies an amplitude reduction of 10.9% and a delay in the time of culmination by 0.016 s. The LS4 signal rise proceeds similarly to the baseline configuration; however, the maximum occurs slightly later, and the peak shape is more rounded and less distinct. After the culmination, the acceleration decreases faster, and the subsequent portion of the curve has a milder course, which shortens the duration of the intensive reaction phase. Overall, the LS4 signal in the chest is characterized by a lower abruptness of changes and a more subdued dynamic profile, suggesting a limitation of the load in the final phase of the crash.

The integrated view of the scenario with a 10 g crash pulse, compiled in

Table 1, confirms the dominant effectiveness of the LS1 variant, which shows clear amplitude dampening in both analyzed segments. In the head, LS1 reduces the peak value relative to the baseline by 62.46% and simultaneously delays the time of maximum by 20 ms, which is reflected by the indicators “Δ% Head vs. REF” and “Δt Head [ms]”. The LS3 variant reduces the amplitude by 22.16%, with a peak delay of 48 ms, while LS4 maintains the resultant value slightly above the baseline (+1.84%) and accelerates the maximum by 4 ms. In the chest, all variants lead to an amplitude reduction. LS1 provides the deepest dampening (−40.63%) and earlier peak occurrence (−20 ms), while LS3 and LS4 act milder (−9.77% and −10.97%), and their maxima are time-shifted towards the end of the pulse. Overall, the compilation confirms that LS1 represents the most protective response character, LS3 is an intermediate system with moderate dampening and delayed reaction, while LS4 exhibits an atypical combination of no dampening in the head and moderate dampening in the chest, with a slight acceleration of the peak in the head part.

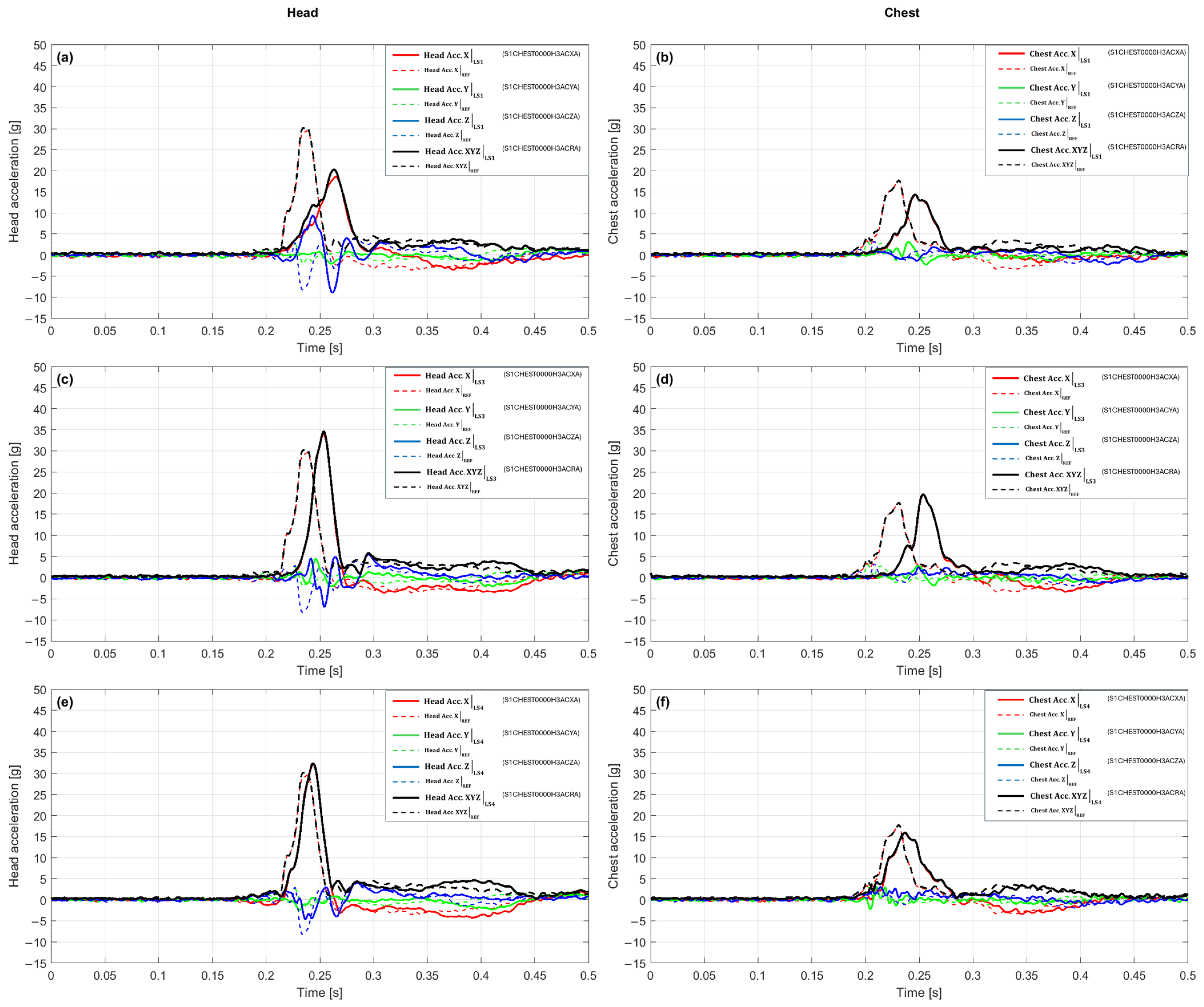

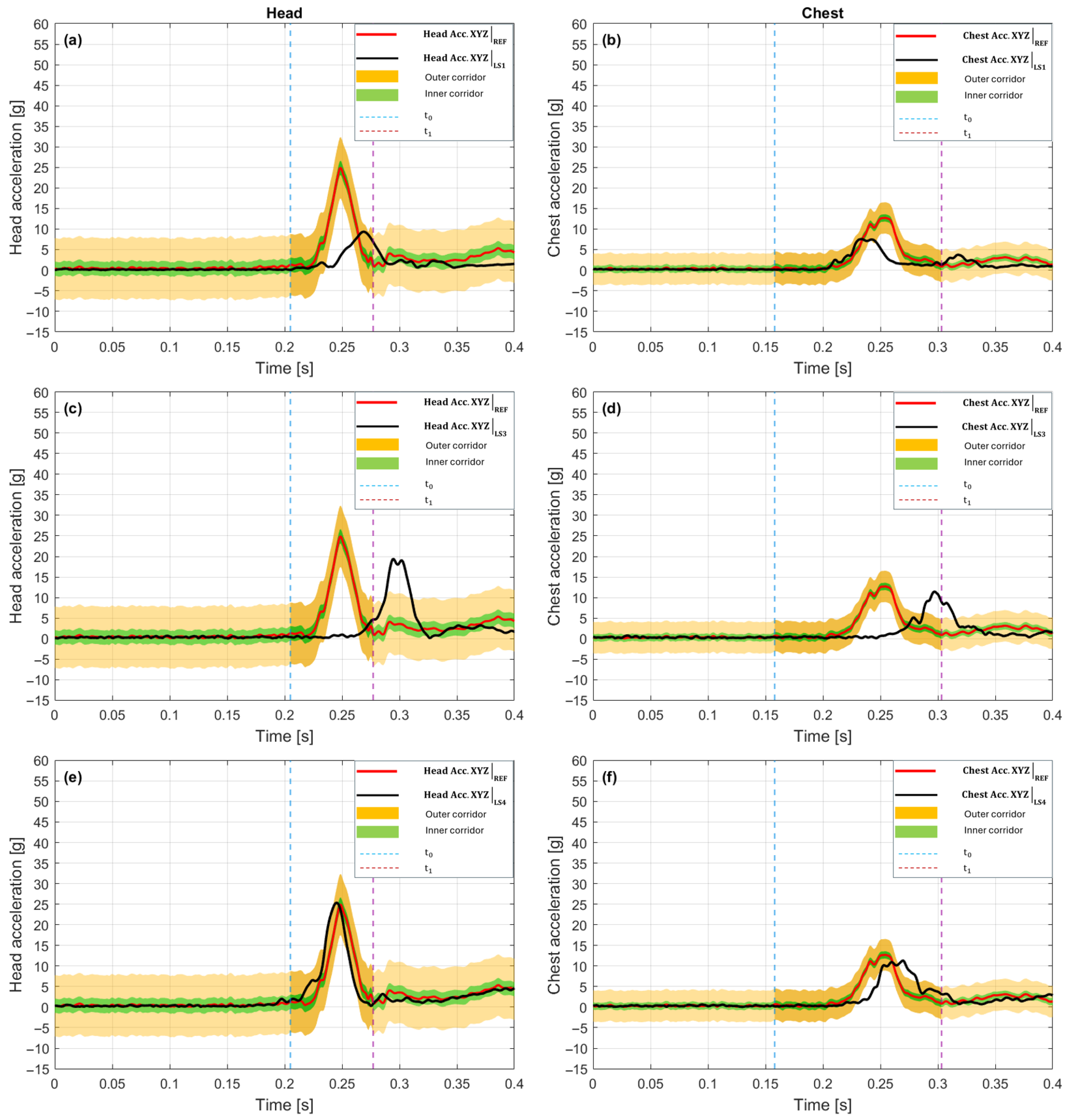

Figure 5a,b presents a comparison of the acceleration waveforms for the LS1 variant and the reference configuration for the 15 g crash pulse. In the head (

Figure 5a), the maximum value in the reference configuration was 30.41 g at 0.238 s, while 20.27 g was recorded in LS1 at 0.263 s. This signifies an amplitude reduction of about 33% and a shift in the time of culmination towards later occurrence by 0.025 s. The shape of the LS1 waveform remains similar to the reference one, but the dynamics of the rise are distinctly milder, and the peak is reached more slowly and at a lower level. After culmination, the signal damps smoothly, without secondary fluctuations. The resultant acceleration value is shaped mainly by the

X-axis component, while the remaining axes do not reach comparable values at the same time. As a result, a reduction in maximum head acceleration and an extended rise time are observed, which indicates more effective pulse dampening in this configuration. In the chest (

Figure 5b), the maximum in the reference configuration was 17.75 g at 0.231 s, and in the LS1 variant, it reached 14.37 g at 0.246 s, which corresponds to an amplitude drop of 19% and a delay in the time of maximum by 0.015 s. In the initial rising phase, the curves are similar; however, in LS1, the signal rises more slowly, and the peak occurs later and at a lower level. After reaching the maximum, the LS1 waveform maintains a gentle character, and the rate of decay remains close to the reference. The largest contribution to the resultant value is again from the

X-axis component, while the transverse components remain relatively small. Overall, LS1 leads to a reduction in peak values and a slowing of the chest reaction dynamics, which confirms its dampening action in the analyzed scenario.

With a 15 g crash pulse, the waveforms for the LS3 variant (

Figure 5c,d) exhibit a distinct shape compared to the reference configuration, both in terms of amplitude and the time of maximum occurrence. In the head (

Figure 5c), a maximum of 34.57 g was recorded at 0.254 s, which corresponds to an amplitude increase of about 14% and a delay in the time of culmination by 0.016 s relative to the baseline. The LS3 variant is characterized by a longer rising phase and a distinct, narrow peak, after which the acceleration rapidly decreases. In the final phase, no additional local maxima occur, and the shape of the waveform remains symmetrical with respect to the culmination. The resultant value at the time of maximum is primarily determined by the

X-axis component, while the components in the Y and Z axes maintain a lower level, which limits their influence on the total acceleration. In the chest (

Figure 5d), the maximum was 19.65 g at 0.254 s, which constitutes an amplitude increase of about 11% and a delay in the time of maximum by 0.023 s. The LS3 waveform shows a faster rise than in LS1, and the culmination is more distinct and shorter in duration. After the peak, a gradual decrease in acceleration is observed without secondary oscillations. The change in the curve shape is similar in both analyzed segments, while maintaining a comparable temporal sequence of signal rise and decay.

In the scenario with a 15g crash pulse, the waveforms for the LS4 variant (

Figure 5e,f) exhibit different behaviors in the head and chest segments. In the head (

Figure 5e), a maximum of 32.39 g was recorded at 0.244 s, which signifies a slight amplitude increase of about 6.5% and a delay in the time of culmination by 0.006 s relative to the reference configuration. The LS4 waveform retains the overall shape of the reference curve, but the rising phase is slightly prolonged, and the acceleration peak occurs slightly later and reaches a higher value. After culmination, a gentle decrease in acceleration is observed without additional local extrema, and the decay profile remains similar to the baseline. The resultant value at the time of maximum continues to be shaped mainly by the

X-axis component, while the components in the Y and Z axes remain at a lower level. In the chest (

Figure 5f), the maximum reached 15.93 g at 0.237 s, which corresponds to an amplitude drop of about 10% and a delay in the time of culmination by 0.006 s relative to the baseline. The LS4 waveform is characterized by a similar beginning of the rise; however, the culmination occurs later and at a lower level. After the maximum, the acceleration decreases smoothly, without secondary amplitude changes. The entire signal maintains a regular shape, and the differences between LS4 and the reference concern mainly the height and time of peak occurrence. The LS4 variant thus maintains a similar temporal course in both analyzed segments, with a slight increase in the peak value in the head and an amplitude reduction in the chest, which confirms the stable and repeatable nature of the response.

The integrated view for the 15 g crash pulse, compiled in

Table 2 for this scenario, shows a clear amplitude and time differentiation between the LS variants. In the head, the reference value is 30.41 g at 0.238 s. The LS1 variant achieves 20.27 g, which signifies an amplitude drop of 33.3%, and the maximum occurs at 0.263 s, 0.025 s later. The LS3 variant yields 34.57 g, representing an increase of 13.7%, with culmination at 0.254 s (+0.016 s relative to the baseline). The LS4 variant achieves 32.39 g, which is 6.5% more than the reference, and the maximum occurs at 0.244 s, signifying a delay of 0.006 s. In the chest, the baseline value is 17.75 g at 0.231 s. The LS1 variant achieves 14.37 g (−19.1%) at 0.246 s (+0.015 s), while LS3 yields 19.65 g (+10.7%) with a maximum at 0.254 s (+0.023 s). The LS4 variant gives 15.93 g, which means a drop of 10.3% and the occurrence of the maximum at 0.237 s (+0.006 s). The compilation of these values in the columns Peak [g], Δ% vs. REF, and t_peak [s] shows that in the head, only LS1 leads to a clear reduction in the peak value, while LS3 and LS4 cause an increase with a slight delay in the time of maximum. In the chest, the differences are more varied, i.e., LS1 and LS4 reduce the amplitude, while LS3 shows a moderate increase, and all variants are characterized by a slight shift in the maximum towards later times. Due to the lack of reliable data for the pelvis, values for this region are not included in the compilation.

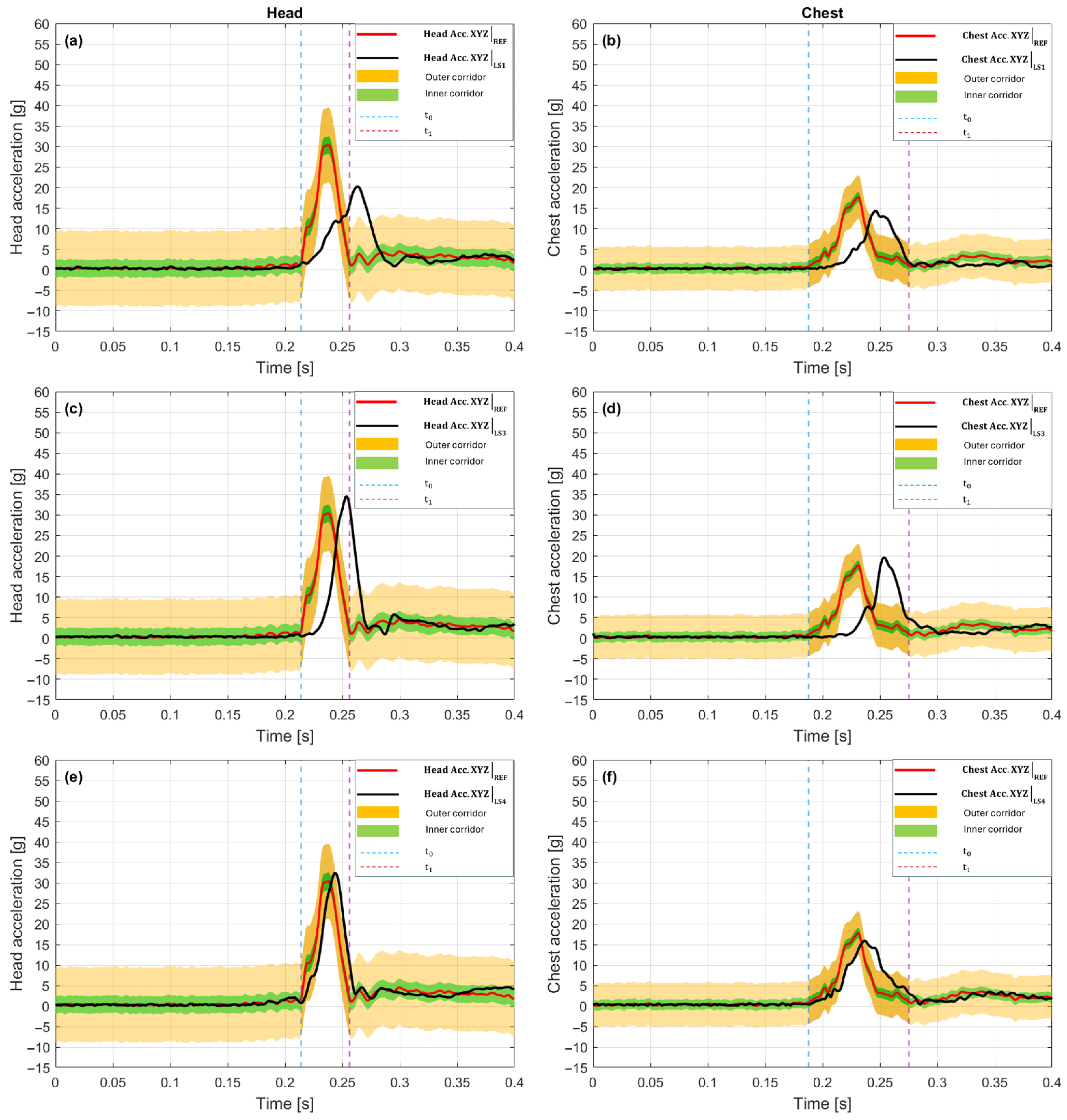

In the 20 g crash pulse scenario, the reference configuration achieved a maximum value of 40.98 g at 0.245 s in the head, and 25.88 g at 0.238 s in the chest. Against this background, the LS1 variant waveforms (

Figure 6a,b) show a reduction in peak values and slight temporal shifts, while maintaining a similar general shape of the response. In the head (

Figure 6a), a maximum of 36.67 g was recorded at 0.249 s, which corresponds to an amplitude drop of 10.5% and a delay in time of culmination by 0.004 s relative to the baseline. The signal rise begins at a similar time; however, in LS1, it has a milder character, the pre-peak slope is less steep, and the transition to maximum is smoother. The culmination occurs slightly later and is characterized by a lower peak value, while after its occurrence, a clear signal dampening is observed without secondary extrema. In the acceleration vector structure, the

X-axis component plays a dominant role, accounting for the main direction of the pulse, while the Y and Z components retain smaller values and do not significantly affect the total maximum. In the chest (

Figure 6b), the maximum was reached at 21.99 g at 0.241 s, which constitutes a reduction of about 15% and a delay of 0.003 s relative to the baseline. In the rising segment, both configurations show a similar course, but in LS1, the value increase process is more temporally distributed, resulting in a milder, less abrupt peak. After reaching the maximum, the signal decays smoothly and stably, without additional local extrema. The LS1 waveform maintains phase consistency with the reference, and both the time of rise initiation and decay occur at the same time points.

In the 20 g crash pulse scenario, the waveforms for the LS3 variant (

Figure 6c,d) indicate a reduction in acceleration peak values and an earlier occurrence of the time of culmination compared to the baseline configuration. In the head (

Figure 6c), a maximum of 38.66 g was recorded at 0.241 s, which corresponds to an amplitude drop of 5.7% and an acceleration of the time of maximum by 0.004 s. The LS3 waveform maintains the general shape of the pulse; however, differences appear in the final rising phase, the values increase slightly slower, and the peak is reached earlier and at a lower value than in the reference configuration. The culmination phase is shorter and more regular, and after its completion, the acceleration decreases smoothly, without secondary extrema. In the acceleration vector structure, the

X-axis component plays a dominant role, while the Y and Z components retain smaller values and do not increase the resultant amplitude. In the chest (

Figure 6d), the maximum was 23.95 g at 0.234 s, which signifies an amplitude reduction of 7.5% and an acceleration of the time of culmination by 0.004 s. The initial LS3 waveform is consistent with the reference configuration; however, in the final rising phase, there is an earlier achievement of a smaller peak value. The pre-peak slope has a similar inclination, while after the maximum, the signal decreases faster and stably, without secondary amplitude changes. At the time of culmination, the

X-axis component remains the dominant element of the acceleration vector, and the other directions show no significant deviations.

In the 20 g crash pulse scenario, the waveforms for the LS4 variant (

Figure 6e,f) show a clear reduction in peak values and a shift in the time of culmination relative to the baseline configuration. In the head (

Figure 6e), the maximum reached 35.26 g at 0.239 s, which corresponds to an amplitude drop of 13.97% and an advancement of the time of maximum by 0.006 s. In the initial phase, the LS4 waveform remains similar to the reference configuration; however, differences become apparent in the final rising segment, the acceleration value increases more slowly, and the peak is reached earlier and at a lower level. The culmination phase is shorter and more symmetrical, and after its completion, the acceleration decreases uniformly, without additional local extrema. The

X-axis component retains its dominant influence on the resultant value, while the Y and Z components maintain lower values and do not cause an increase in the total amplitude. In the chest (

Figure 6f), a maximum of 20.89 g was recorded at 0.231 s, which signifies an amplitude reduction of 19.27% and an advancement of the time of culmination by 0.007 s. The shape of the LS4 waveform in the initial phase is consistent with the baseline; however, in the final rising part, an earlier achievement of the maximum value and a lower peak level are observed. After culmination, the signal drops stably, and its temporal course remains regular and devoid of secondary fluctuations. The changes are quantitative: they do not affect the general structure of the waveform, but they clearly indicate a limitation of the maximum acceleration values relative to the baseline configuration.

The summary of the results for the 20 g crash pulse scenario, which presents a complete picture of the amplitude and temporal changes between the baseline configuration and the LS1, LS3, and LS4 variants, is shown in

Table 3. The reference values for this scenario are 40.98 g at 0.245 s in the head and 25.88 g at 0.238 s in the chest. In the head, the LS1 configuration achieved a maximum of 36.67 g at 0.249 s, which represents a drop of 10.53% and a delay in the time of culmination by 0.004 s. The LS3 variant shows a maximum of 38.66 g at 0.241 s, meaning a drop of 5.67% and an advancement of the peak by 0.004 s, while LS4 recorded 35.26 g at 0.239 s, which signifies an amplitude reduction of 13.97% and an advancement of the time of maximum by 0.006 s. As a result, all LS variants lead to an amplitude reduction while maintaining a similar waveform shape and slight temporal differences. In the chest, the reference value was 25.88 g at 0.238 s. The LS1 variant reached 21.99 g at 0.241 s, which corresponds to a reduction of 15.00% and a delay of 0.003 s. For LS3, the maximum was 23.95 g at 0.234 s, meaning a drop of 7.46% and an advancement of 0.004 s, while LS4 yielded 20.89 g at 0.231 s, which corresponds to a reduction of 19.27% and an advancement of 0.007 s. These values indicate a consistent amplitude reduction in the chest for all variants, with differences in peak chronology not exceeding a few milliseconds. The compilation of results in the columns Peak [g], Δ% vs. baseline, and t_peak [s] confirms the consistency of the trends between the analyzed segments. In the head and chest, the LS variants lead to a reduction in maximum values ranging from 5% to 19%, while maintaining a similar temporal course. The differences primarily concern amplitude, while changes in the time of peak occurrence range from −0.007 to +0.004 s, which indicates the maintenance of a uniform temporal characteristic throughout the entire system.

3.2. RMSE Analysis

For the 10 g crash pulse in the head, the RMSE aligned values ranged from 0.79 g for LS1 to 0.91 g for LS3, with an intermediate value of 0.85 g for LS4 (

Table 4). After amplitude matching (which involved proportionally strengthening or weakening the LS signal so that its range of values corresponded to the reference signal), the errors decreased to 0.54 g (LS1), 0.63 g (LS3), and 0.59 g (LS4). The error reduction of about 30% indicates that the main differences between LS and the baseline resulted from the LS sensors recording the same waveform but with a slightly lower intensity.

The LS1 variant achieved the highest agreement with the reference waveform, both before and after amplitude matching. This means that LS1 faithfully reproduced the temporal structure of the signal, and the differences resulted primarily from the level of recorded acceleration. The LS3 variant maintained a similar signal shape, but its amplitude was further removed from the baseline. LS4 held an intermediate position: the waveform was well matched in time, but it still exhibited a lower intensity of accelerations relative to the reference configuration.

For the chest, the RMSE aligned errors were higher and averaged 1.02 g for LS1, 1.10 g for LS3, and 1.05 g for LS4. After amplitude matching, they dropped to 0.74 g, 0.81 g, and 0.78 g, respectively. This trend is consistent with the observations for the head; LS1 maintained the best fit, LS3 was characterized by a larger error, and LS4 ranked in between them. This means that LS1 most faithfully reproduced both the shape and the rate of acceleration changes, LS3 recorded a signal with greater dispersion and amplitude differences, and LS4 maintained correct chronology but with less precision in intensity mapping.

The average temporal shifts between the LS signals and the reference amounted to about 9–11 ms. The largest delay occurred for LS3, and the smallest for LS1. The adopted evaluation threshold was ±8 ms; thus, in some tests, the temporal differences were slightly larger. From the perspective of dynamic measurements, however, these values fall within the range considered acceptable, in accordance with the guidelines of SAE J211/1 (Instrumentation for Impact Test—Part 1: Electronic Instrumentation) and ISO 6487:2022 (Road vehicles—Measurement techniques in impact tests—Instrumentation), which specify acceptable temporal differences at the level of ±10 ms.

A comparison of the RMSE aligned and RMSE scaled values shows that amplitude matching reduced the error by 25–30%, which means the dominant source of differences between LS and REF was lower signal intensity, and not a different waveform shape (

Table 4). The LS1 variant achieved the smallest total error (0.54 g after matching), which demonstrates the best agreement with the baseline. LS3 was characterized by the largest error (0.63 g) and the largest delay, while LS4 held an intermediate position; the errors were moderate, and temporal synchronization remained correct.

In the 15 g crash pulse scenario, for the head, the RMSE aligned values were: 0.83 g for LS1, 1.04 g for LS3, and 0.91 g for LS4 (

Table 5). After introducing amplitude matching, meaning proportional strengthening or weakening of the LS signal so that its value range overlapped with the reference signal, the error was reduced to 0.58 g (LS1), 0.72 g (LS3), and 0.63 g (LS4). The error reduction of about 25–30% indicates that the main cause of the differences between LS and REF was the varying intensity of recorded accelerations, and not the distortion of the waveform shape. Among the analyzed variants, LS1 most accurately reproduced the reference signal, LS3 showed greater amplitude deviations and less stable mapping in time, while LS4 held an intermediate position; the shape and phase of the signal were well matched, though the amplitude remained somewhat lower than in the reference configuration.

In the case of the chest, the RMSE aligned values were higher and averaged 1.15 g for LS1, 1.26 g for LS3, and 1.19 g for LS4. After applying amplitude matching, the error dropped to 0.83 g (LS1), 0.95 g (LS3), and 0.88 g (LS4). The same pattern held as for the head: LS1 provided the best fit, LS3 generated the largest deviations, while LS4 ranked in between them. This means that the LS1 variant most faithfully reproduced both the waveform shape and the dynamics of acceleration changes, LS3 recorded a more dispersed signal burdened with larger amplitude differences, and LS4 correctly mapped the chronology of events, but with moderately reduced intensity relative to the baseline.

The compilation of RMSE aligned and RMSE scaled shows that amplitude matching allowed for an error reduction of 25–30%, which confirms that the key source of divergence between LS and REF was the differences in signal strength, and not its shape (

Table 5). The LS1 variant achieved the most favorable parameters, the smallest total error after scaling (0.58 g) and the most stable temporal mapping. In contrast, LS3 was characterized by the highest error values (0.72 g) and local temporal shifts, while LS4 maintained a correct waveform shape, but with moderately reduced amplitude.

In the 20 g crash pulse scenario, for the head, the obtained RMSE aligned values were 0.92 g for the LS1 configuration, 1.18 g for LS3, and 1.01 g for LS4 (

Table 6). After applying amplitude matching (meaning linear scaling of the LS signal so that its range overlapped with the range of the reference signal), the error values decreased to 0.68 g (LS1), 0.84 g (LS3), and 0.73 g (LS4). The drop of the order of 25–30% indicates that the essential difference between the LS and REF signals resulted from the level of acceleration amplitude, and not from significant distortions of their waveform shape. LS1 proved to be the variant with the smallest error and highest convergence with the baseline waveform; LS3 was characterized by the largest deviations both in terms of amplitude and temporal mapping, while LS4 ranked in between them, ensuring correct temporal matching with a slightly weaker signal intensity.

For the chest, the RMSE aligned values were generally higher and amounted to 1.22 g (LS1), 1.34 g (LS3), and 1.28 g (LS4). After introducing amplitude matching, an error reduction was recorded to 0.90 g for LS1, 1.03 g for LS3, and 0.95 g for LS4. The pattern of dependencies remained similar to that observed for the head: LS1 consistently generated the lowest error values, LS3 was characterized by the most dispersed signal and larger response delays, while LS4 maintained intermediate results. In practice, this means that LS1 most faithfully reproduced the reference signal in terms of both shape and the rate of acceleration changes, LS3 showed the largest amplitude and chronology discrepancies, and LS4 maintained a correct waveform with somewhat reduced intensity.

A comparison of RMSE aligned with RMSE scaled shows that the application of amplitude scaling allowed for an error reduction of about 25–30%, which confirms that the discrepancies between LS and REF were primarily characterized by differences in signal strength, and not in its shape (

Table 6). The LS1 variant achieved the lowest total error after scaling (0.68 g) and the most stable temporal mapping. The LS3 configuration remained burdened with the largest deviations (0.84 g) and local temporal shifts, while LS4 was characterized by a moderate error level (0.73 g) while maintaining correct synchronization with the reference signal.

3.3. CORA Waveform Analysis

In the 10 g crash pulse scenario, the LS1 variant (

Figure 7a—Head,

Figure 7b—Chest) showed pronounced temporal shifts and amplitude differences relative to the baseline, despite very high waveform shape match in both analyzed areas. In the head, the time shift = +18 ms value signifies a delay relative to the reference waveform by 18 ms, and P_phase = 0.000 confirms a lack of phase match in the analysis range [t

0, t

1].

Figure 7a shows that the LS1 peak occurred later than the maximum of the reference signal (red line), and the waveform remained outside the tolerance corridor for most of the time, which is reflected in the low C1_corridor value of 0.422. Additionally, G_size = 0.176 means that the total energy of the LS1 signal in the head is lower by as much as 82.4% relative to the baseline. Despite this, V_progression = 0.993 and Kmax = 0.987 confirm a very high curve shape match.

In the chest (

Figure 7b), an inverse shift character is indicated; in this case, a time shift = −12 ms means that the LS1 signal maximum occurred 12 ms earlier than in the reference waveform. This value is still significant, but the influence on the phase metric is smaller, P_phase = 0.172, which signifies partial temporal match. The tolerance corridor coverage is better than in the head, C1_corridor = 0.679, confirming a larger part of the signal remains within the outer corridor. The signal amplitude in the chest remained reduced, G_size = 0.347, which signifies an energy drop of over 65% relative to the baseline.

The shape maintains a very good match (V_progression = 0.996, Kmax = 0.991). The overall scores C_total for both areas are similar, 0.406 (Head) and 0.592 (Chest), indicating a relatively uniform, though low level of match.

A common element in the behavior of the LS1 system in both areas is the consistent waveform profile (V_progression > 0.99), while the main sources of mismatch remain amplitude differences and temporal shifts, which have opposite signs—a delay in the head (+18 ms) and an advancement in the chest (–12 ms).

The LS3 variant shown in

Figure 7c for the head and

Figure 7d for the chest exhibited the most pronounced temporal delays in the entire group. In the head, the time shift = +42 ms signifies that characteristic waveform features (e.g., maximum acceleration) occurred 42 ms later than in the reference waveform. Such a large delay results in a P_phase value = 0.000, which by CORA definition means total lack of temporal match in the designated window [t

0, t

1] [

57]. Despite this, the shape match remains high (V_progression = 0.994, Kmax = 0.989), indicating that the signal structure was well mapped, but shifted in time. The G_size value = 0.381 means that the total signal energy is lower by 61.9% relative to the baseline.

Figure 7c confirms this assessment: the LS3 curve (black) rises similarly to the reference, but reaches its peak with a large delay, outside the central analysis zone. A significant part of the waveform is outside the tolerance corridor, resulting in C1_corridor = 0.467. The overall match score C_total = 0.463 is lower than in LS1, which primarily results from the larger phase shift. In the chest, the delay is more pronounced. Time shift = +53 ms, which again translates to P_phase = 0.000. The maximum acceleration in LS3 occurred 53 ms after the reference peak moment. On

Figure 7d, this phase drift was visible as the main peak shifted toward the end of the time window. Tolerance corridor coverage was weaker than in the head. C1_corridor = 0.508. Despite the shift, the waveform shape remains coherent (V_progression = 0.992, Kmax = 0.983), and the amplitude reaches the highest level among the analyzed variants. G_size = 0.927, meaning only 7.3% lower than the baseline. The overall score C_total = 0.574 is slightly higher than in the head, but still remains in the range of an incomplete match.

The LS3 performance is characterized by high shape and amplitude coherence, but its main limitation in both areas is the significant temporal shift. High time shift values in the head (+42 ms) and the chest (+53 ms) suggest a global delay in the reaction of the LS3 measurement system.

The LS4 variant (

Figure 7e,f) presents the best coherence with the baseline in both areas. In the head, the temporal difference relative to the reference was time shift = −5 ms, meaning the LS4 signal maximum occurred 5 ms earlier than in the reference waveform. This value falls within the typical error tolerance and results in P_phase = 0.306, which signifies partial phase match.

Figure 7e shows that the LS4 peak is very close to the reference peak, and a significant part of the waveform is within the outer corridor, with fragments covering the inner corridor. This is also confirmed by the metrics, C1_corridor = 0.505, V_progression = 0.997, G_size = 0.913, Kmax = 0.994. The overall score C_total = 0.622 is the highest among all analyzed configurations in the head. In the chest, a positive temporal shift was observed: time shift = +15 ms, which translates to P_phase = 0.000. This result is lower than in the head. The main maximum of the LS4 signal occurs here, 15 ms after the baseline, which indicates nonuniform dynamics of pulse propagation along the body.

Figure 7f shows that although the signal shape is well mapped (V_progression = 0.994, Kmax = 0.989), and the amplitude reaches 87.6% of the baseline value (G_size = 0.876), the phase differences cause the overall score to drop to C_total = 0.595. Tolerance corridor coverage is comparable to the head (C1_corridor = 0.567).

The LS4 variant features the most balanced match profile (both in relation to shape and amplitude) and relatively low temporal shifts. There is a difference in the sign of the time shift between the head (–5 ms) and the chest (+15 ms).

The LS1 variant in the 15 g crash pulse (

Figure 8a—Head,

Figure 8b—Chest) was characterized by reduced match quality in terms of both amplitude and phase match, despite high signal shape correlation. In the head, the temporal shift value time shift = +12 ms indicates that the maximum of the analyzed signal occurs 12 ms after the peak in the reference waveform. Such a difference causes the P_phase = 0.000, which, according to the CORA assessment standard, corresponds to total lack of temporal match in the analyzed window [

57]. For the head

Figure 8a, the value C1_corridor = 0.168 indicates very limited tolerance corridor coverage. A significant portion of the LS1 signal in the head lies outside the permissible range relative to the baseline. The observed discrepancies are amplified by the low G_size value = 0.228, which means a drop in total dynamic energy of over 77% relative to the reference waveform. Nevertheless, the curve shape match is still very high (V_progression = 0.991, Kmax = 0.982), meaning that the LS1 signal in the head retains a structure similar to the baseline, but is weaker and temporally shifted. Consequently, the overall match quality score (C_total = 0.287) is low. In the chest (

Figure 8b), an even larger temporal shift was recorded: Time shift = +23 ms, which again translates to P_phase = 0.000.

Figure 8b indicates that the LS1 signal maximum occurs noticeably after the reference signal peak, and this shift has a direct impact on the match within the analysis window. However, the signal amplitude is significantly closer to the baseline values than in the case of the head. G_size = 0.773, which means an energy reduction of about 22.7%. Tolerance corridor coverage is also slightly higher than in the head, C1_corridor = 0.237, but still remains below the acceptable level. The signal temporal structure is consistent with the baseline: V_progression = 0.995, Kmax = 0.991, suggesting correct mapping of the overall waveform. The overall score C_total = 0.413 is slightly better than in the head.

The LS3 variant in the 15 g crash pulse (

Figure 8c—Head,

Figure 8d—Chest) presents a match profile with very high signal shape match relative to the reference signal (baseline), but with a significant temporal shift problem and partial amplitude mismatch. In the head, a time shift = +16 ms indicates a delay of the LS3 signal relative to the reference waveform by 16 ms. Such a shift results in a P_phase metric = 0.000, which, according to the CORA assessment model, signifies a lack of phase match in the defined analysis window [

57]. Simultaneously, tolerance corridor coverage C1_corridor = 0.096 is highly restricted. Less than 10% of the signal falls within the expected range around the baseline waveform. This means that the signal temporal profile, although structurally similar, is shifted enough that it ceases to be acceptable within the adopted evaluation limits. The waveform amplitude remains moderately lower than the reference (G_size = 0.848), corresponding to a reduction in dynamic energy of approximately 15.2%. Despite these mismatches, the curve shape analysis indicates very strong correlation (Kmax = 0.9948) and waveform consistency (V_progression = 0.9974). The cumulative score C_total is 0.356.

For the chest, the metric values present a similar pattern. Time shift = +29 ms signifies a significant delay, which also results in P_phase = 0.000. The value C1_corridor = 0.213 suggests that only about 21% of the LS3 signal is within the permissible corridor. Despite this, the amplitude is very close to the reference (G_size = 0.899), and the structural match remains at a high level (V_progression = 0.994, Kmax = 0.9888). The overall score C_total = 0.422 remains low, but better than in the head, mainly due to better amplitude match and slightly greater corridor coverage.

The LS3 variant in the 15 g crash pulse is characterized by very good signal shape mapping quality (Kmax > 0.98 for both areas), but only partial amplitude match (G_size < 0.9) leads to a low final score (C_total < 0.45).

The LS4 variant in the 15 g crash pulse is characterized by the best mapping quality of all three configurations relative to the reference signal, both in the head and the chest.

Figure 8e and f show that LS4 maintains very good convergence with the reference waveform across the entire evaluation window. In the case of the head, a time shift = +6 ms indicates a slight delay relative to the reference signal peak. The value P_phase = 0.000 means that despite this delay, the temporal match is formally low in the CORA metric (because the delay exceeded the penalization threshold) [

57]. Despite this limitation, the signal shape match remains almost ideal. V_progression = 0.9986, Kmax = 0.9972, which proves strong correlation of the LS4 waveform with the reference. The amplitude metric G_size = 0.934 means that the total dynamic energy was mapped with very little loss (~6.6%). Tolerance corridor coverage was also noticeably better than in LS1 and LS3 (C1_corridor = 0.242), although still below half. As a result, the overall score C_total = 0.443 is the highest among the variants analyzed so far for the head in this scenario.

In the chest, the LS4 configuration also presented a better match. Time shift = +11 ms is moderate, but it again results in P_phase = 0.000 due to exceeding the acceptable delay. Nevertheless, both the amplitude match (G_size = 0.938) and shape correlation (V_progression = 0.989, Kmax = 0.978) are high. Tolerance corridor match C1_corridor = 0.370 is the best of all cases analyzed so far, indicating a significant improvement in signal coverage relative to the reference waveform. The final value C_total = 0.506 is the only instance in this scenario where the overall match exceeded the 0.5 threshold.

The LS1 variant in the 20 g crash pulse scenario showed a clear improvement in match quality relative to previous scenarios, reflected in both the partial and final scores. In the head (

Figure 9a), the time shift = +3 ms value indicates a very slight delay of the signal relative to the reference waveform. The P_phase value = 0.286 suggests that the shift is within the range where the phase score does not drop to zero, but is partially penalized. A significant improvement was achieved in tolerance corridor match. C1_corridor = 0.636, which means over 63% of the LS1 signal was within the defined evaluation range around the reference. This is a significantly higher level of match than in previous scenarios. The resultant amplitude was mapped moderately well (G_size = 0.719), corresponding to a reduction in dynamic energy of approximately 28%. Shape correlation remained very high (Kmax = 0.983, V_progression = 0.992), confirming that LS1 maps the dynamic profile with high precision. The cumulative score C_total = 0.651 qualifies as a moderately high result. In the chest (

Figure 9b), this trend continued. The delay was time shift = +5 ms, which also fell within the range of partial temporal penalization (P_phase = 0.425). The C1_corridor score = 0.698 indicates that almost 70% of the signal was inside the permissible corridor, representing the best result of all previous LS1 cases. Amplitude match G_size = 0.770 suggests a slight underestimation of overloads, but without serious impact on signal quality. The waveform shape was preserved with very high accuracy (V_progression = 0.996, Kmax = 0.993), ensuring a final score C_total = 0.714.

The LS3 variant in the 20 g crash pulse achieves the best results of all previous configurations, both in terms of temporal and structural match, and also regarding amplitude mapping. For the head

Figure 9c, the signal delay relative to the REF signal was practically negligible. Time shift = −3 ms, resulting in a relatively high temporal score, P_phase = 0.286.

The LS3 waveform coverage relative to the tolerance corridor was C1_corridor = 0.532, meaning that more than half of the signal fell within the tolerance range around the baseline waveform. Structural parameters achieved values close to the maximum: Kmax = 0.9987 and V_progression = 0.9994, confirming an almost ideal signal shape match. Amplitude match was also very high (G_size = 0.913), giving only an approximately 9% difference in dynamic energy between LS3 and the reference. The final value C_total = 0.632 classifies LS3 as a highly convergent configuration, particularly against previous results.

For the chest (

Figure 9d), LS3 achieved an even higher score. Time shift = −1 ms means that the LS3 waveform was nearly synchronous with the reference. This is confirmed by the phase score P_phase = 0.885, which is the highest among the cases analyzed so far. The value C1_corridor = 0.861 means that 86% of the signal fell within the tolerance corridor. This is also the highest recorded result for this metric. Structurally, the waveform was still very well matched (Kmax = 0.984, V_progression = 0.992), and the amplitude match G_size = 0.927 suggests minimal differences in overload levels. The final value C_total = 0.898 not only exceeded the 0.80 threshold but also indicates that LS3 can be treated as a reference variant for this scenario.

In the LS4 configuration for the 20 g crash pulse, a clear discrepancy in match quality was noticeable between the head and the chest. Although a very good structural signal match was maintained in both cases, the results of the C_total metric differ depending on the sensor location. For the head (

Figure 9e), time shift = −6 ms indicates a slight lead of the LS4 waveform relative to the REF signal. However, P_phase = 0.0 suggests that this shift exceeded the temporal metric penalization threshold, which lowered the final score. Simultaneously, V_progression = 0.998 and Kmax = 0.996 prove almost ideal signal shape match, confirming that temporal misalignment is the only serious factor limiting the final score. Tolerance corridor coverage C1_corridor = 0.278 was relatively low, which was partially due to the earlier occurrence time of the peak, causing the LS4 signal to fall outside the main evaluation window.

Amplitude was mapped well, with G_size = 0.859, meaning a difference of around 14% relative to the reference energy. The overall value C_total = 0.448 is classified as an intermediate result, dominated by high waveform correlation and acceptable amplitude mapping. For the chest (

Figure 9f), the situation was significantly more favorable. Temporal shift was eliminated (time shift = 0 ms), resulting in a P_phase score = 1.0 (full temporal match). Tolerance corridor coverage was high. C1_corridor = 0.710, meaning that over 70% of the LS4 signal fell within the defined tolerance range around the reference waveform. Amplitude match G_size = 0.929 and correlation Kmax = 0.962 (with V_progression = 0.981) prove high-quality mapping in terms of both energy and dynamic structure. The final value C_total = 0.840 exceeds the 0.80 threshold, classifying this case as technically very good and close to the reference configuration.

Comparing the results of variants LS1, LS3, and LS4 across different crash pulses, clear differences in the quality of mapping the model’s dynamic response relative to the reference waveforms were observed, both in the head and the chest (

Table 7). The LS1 variant was characterized by significant variability between crash pulses. In the 10 g crash pulse, it exhibited low C_total values (0.287 for Head, 0.413 for Chest), mainly due to significant temporal shifts (time shift = +12 ms and +23 ms), which resulted in total lack of phase match (P_phase = 0.000) and low tolerance corridor coverage (C1_corridor < 0.24). Despite a high shape match (Kmax > 0.98), a low level of dynamic energy (G_size close to 0.2) further lowered the final score. In subsequent crash pulses, this quality gradually improved: in the 20 g crash pulse, time shift decreased to +3/+5 ms, P_phase increased (to 0.286 and 0.425), and C1_corridor reached values above 0.63. Ultimately, LS1 in the 20 g crash pulse achieved C_total = 0.651 for Head and 0.714 for Chest, indicating a clear improvement in mapping, particularly in terms of synchronization and corridor coverage.