Collaborative Control for a Robot Manipulator via Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method and Extremum Seeking Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

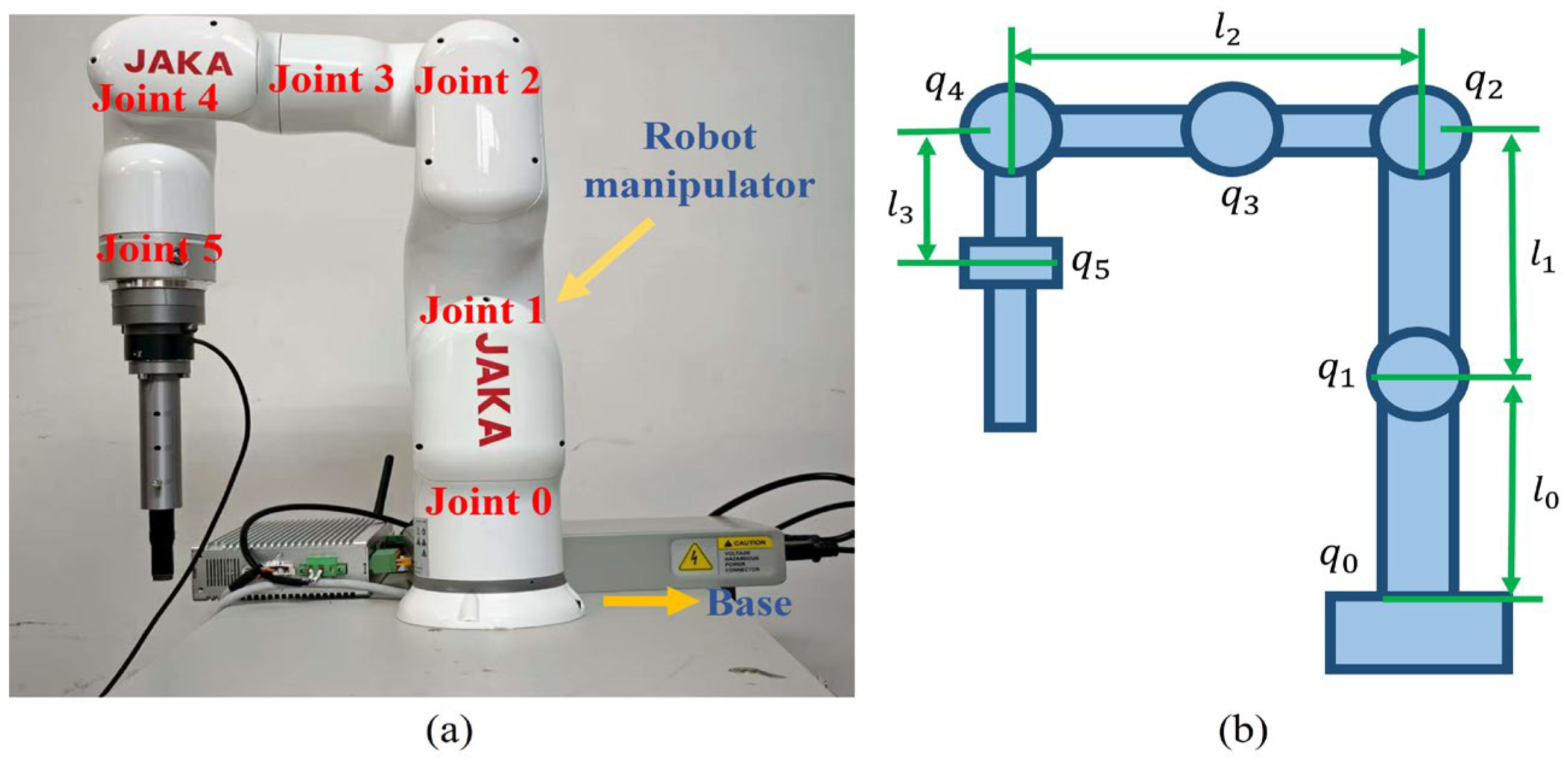

2.1. Dynamic Model of Robot Manipulator

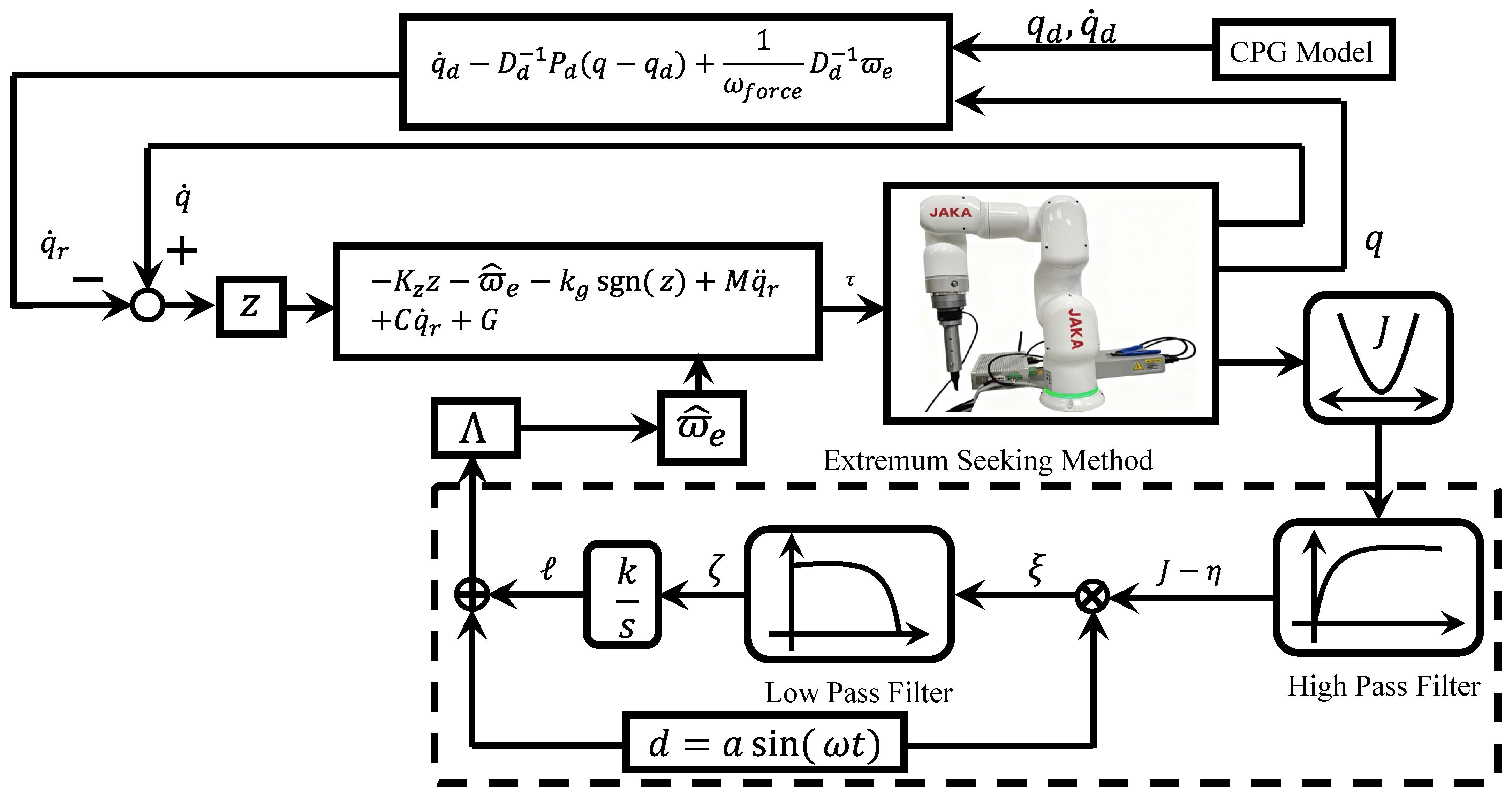

2.2. Extremum Seeking Optimization

2.3. Control Development

2.3.1. Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method

2.3.2. Stability Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiments Setup

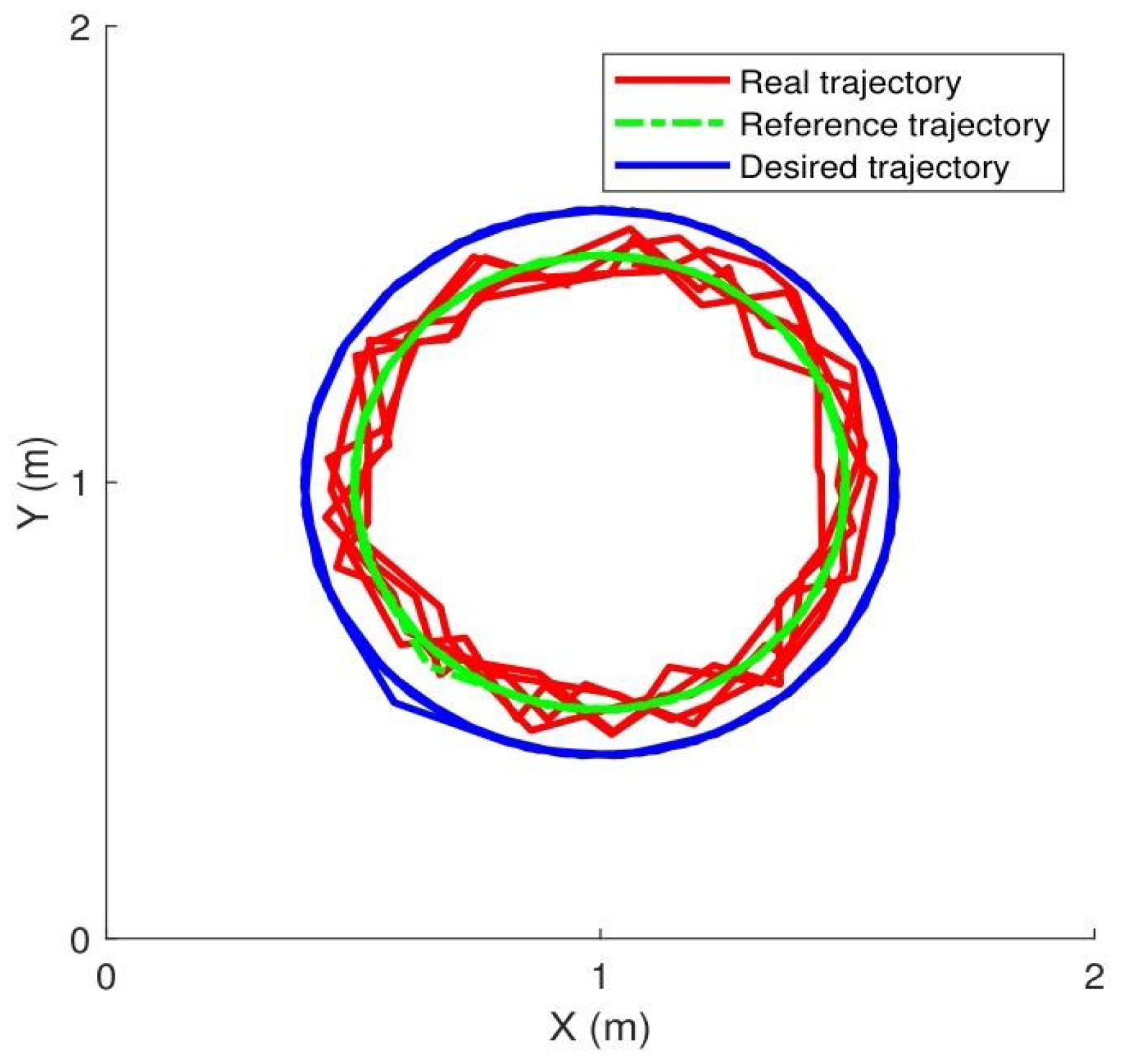

3.2. Case 1: Manipulator Tracking a Circular Motion

- (1)

- Experiment: The circular motion tracking task in Case 1 control strategy. A circular path was defined as the reference trajectory, which the robot’s end-effector was commanded to track. However, owing to the influence of contact force, the proposed impedance method regulated the desired trajectory to the reference trajectory. Finally, the controller computed motor torques to drive the end-effector along the reference trajectory while maintaining a consistent contact force level. The combined cost function was designed with tracking errors and the contact force change. An extremum seeking approach is introduced to optimize the composite cost function . The suitable control parameters are selected to help the manipulator match the correct and appropriate tracking trajectory.

- (2)

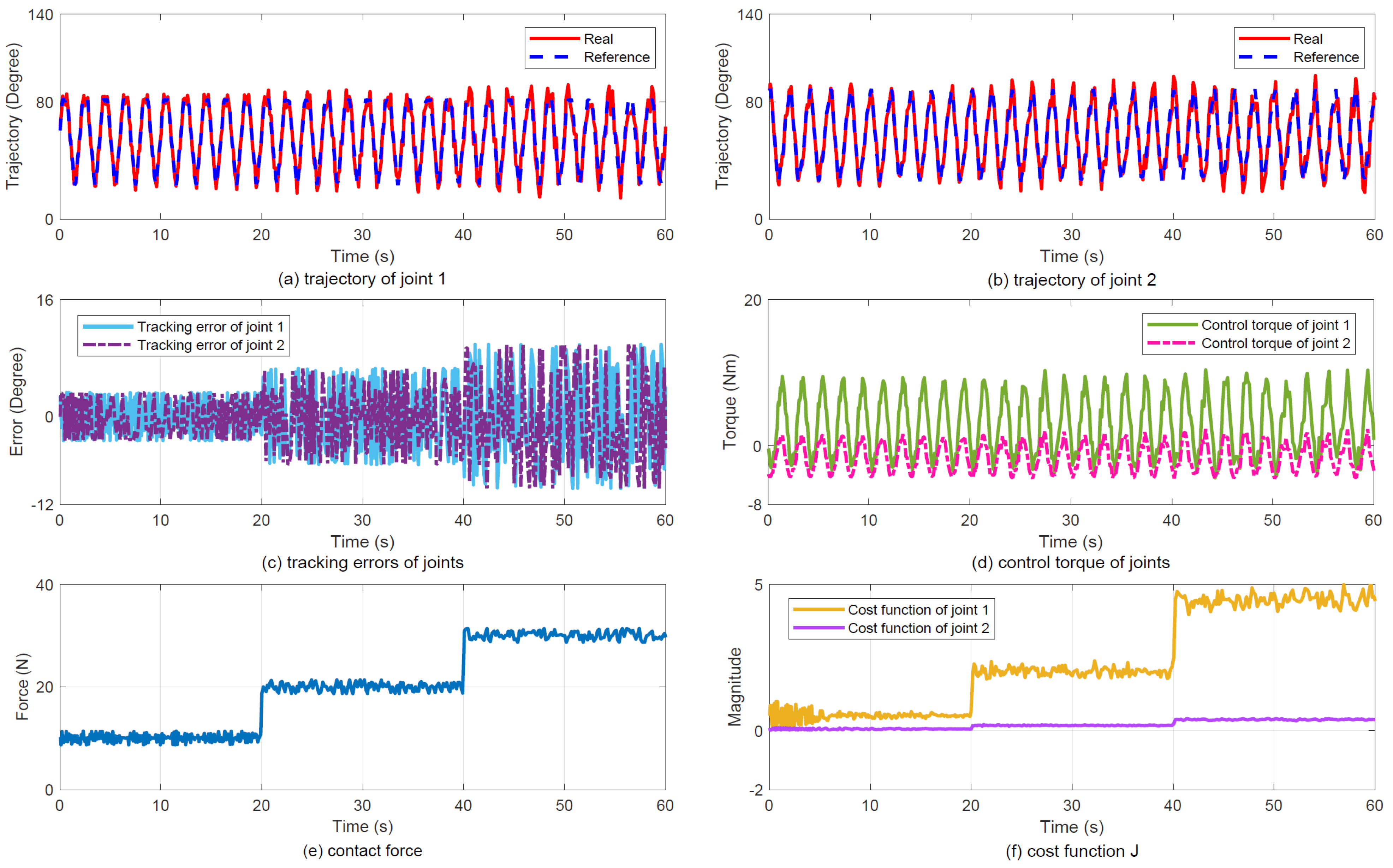

- Results: Figure 5 illustrates the experimental tracking performance, with subplots (a) and (b) displaying joint trajectories, (c) presenting joint tracking errors, (d) showing control torque profiles, (e) depicting contact force variations, and (f) demonstrating the evolution of cost function J. The results indicate that the proposed controller achieves smoothly varying force regulation.

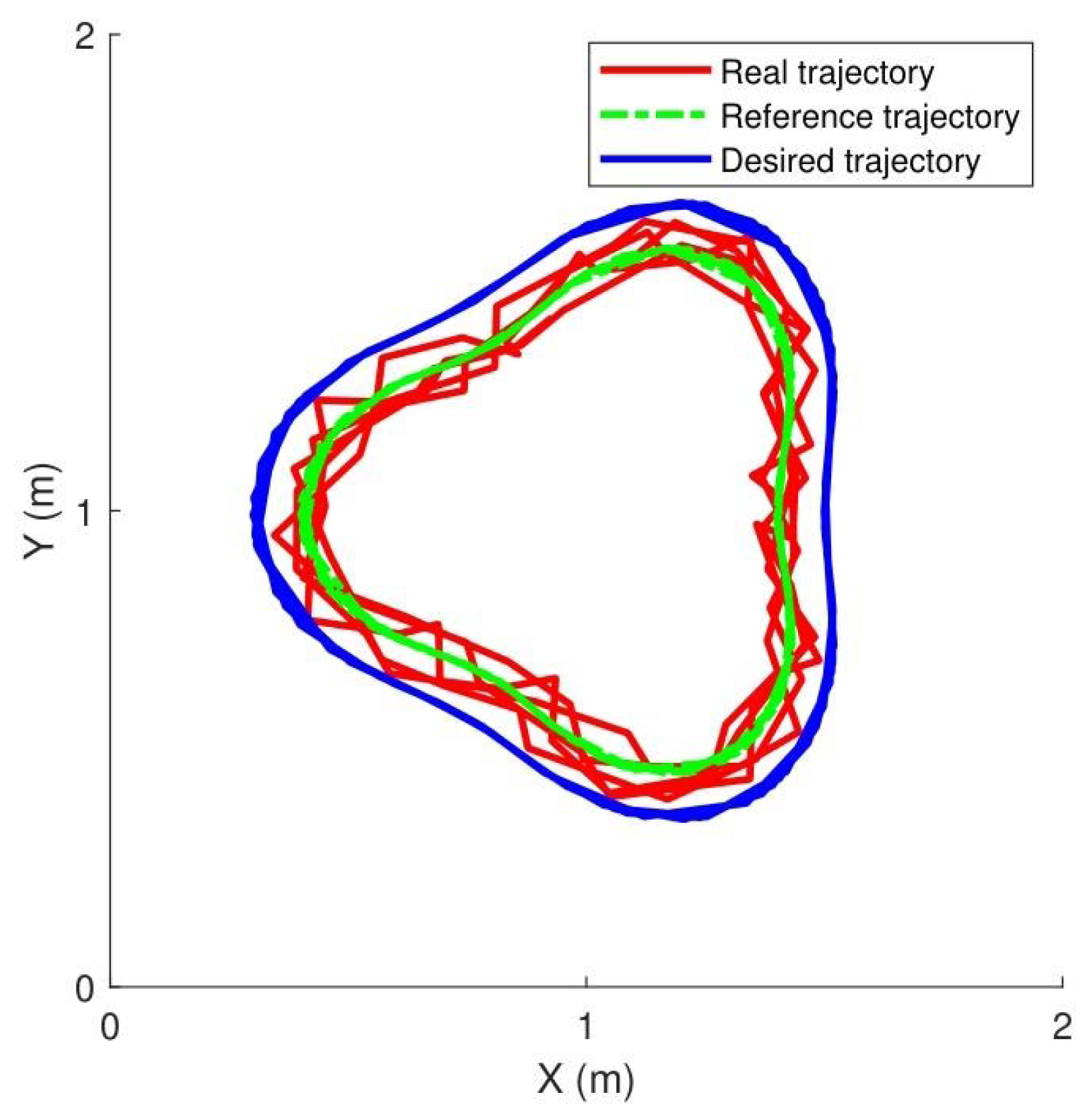

3.3. Case 2: Manipulator Tracking a Triangular Motion

- (1)

- Experiment: Case 2 evaluates how the proposed controller performs in a triangular circular path tracking task. The desired trajectory was designed as a triangular circle. The robotic end-effector was regulated to follow the predefined trajectory. However, due to the effect of contact force, the proposed impedance method aligned the desired trajectory with the reference trajectory. The controller computed the motor torques necessary to guide the robotic end-effector along the reference trajectory. In the process, the manipulator maintained the contact force at a fixed level. The combined cost function J was designed with tracking errors and the contact force change. An extremum seeking strategy is employed to optimize the aggregate cost function J. The suitable control parameters are selected to help the manipulator match the correct and appropriate tracking trajectory.

- (2)

- Results: Figure 7 summarizes the experimental tracking performance, with subfigures (a) and (b) illustrating joint tracking results, (c) displaying joint errors, (d) presenting control torque, (e) showing contact force variations, and (f) depicting the evolution of cost function J. The results demonstrate smooth force regulation achieved by the proposed controller.

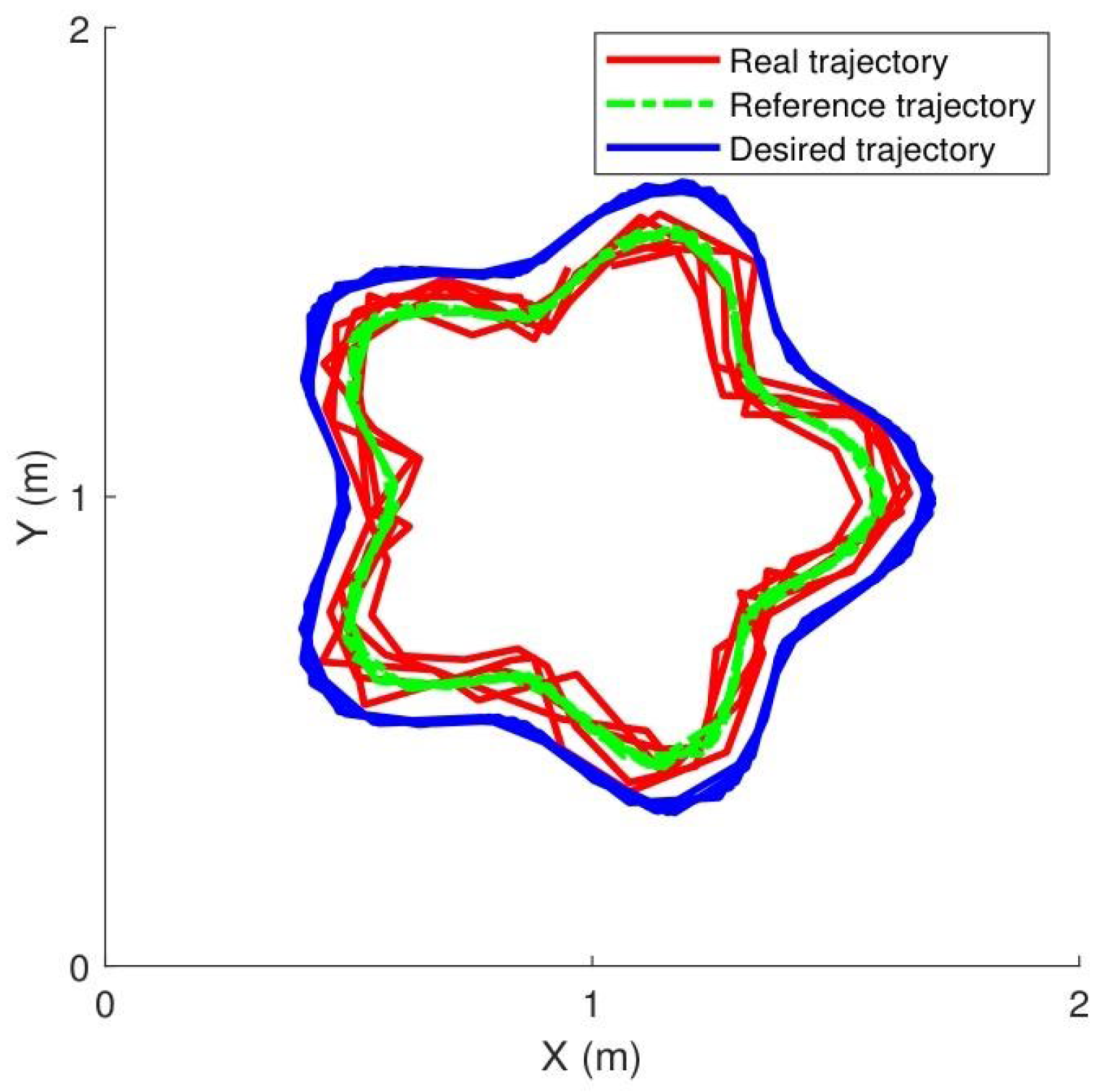

3.4. Case 3: Manipulator Tracking a Sine Circular Motion

- (1)

- Experiment: Case 3 evaluates the controller’s performance through a sinusoidal circular path tracking task, where the robot’s end-effector is guided along a predefined sinusoidal trajectory. However, due to the effect of contact force, the proposed impedance method regulated the desired trajectory to the reference trajectory. The controller computed the motor torques required to drive the robotic end-effector along the reference trajectory. In the process, the contact force was maintained at a fixed level. The combined cost function J was designed with tracking errors and the contact force change. An extremum seeking strategy is introduced to optimize the aggregate cost function J. The suitable control parameters are selected to help the manipulator match the correct and appropriate tracking trajectory.

- (2)

- Results: Figure 9 presents the experimental tracking performance, with subfigures (a) and (b) illustrating joint trajectories, (c) displaying tracking errors, (d) showing control torque profiles, (e) depicting contact force variations, and (f) demonstrating the evolution of cost function J. The results confirm smooth force regulation achieved by the proposed controller.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kommuri, S.K.; Han, S.; Lee, S. External torque estimation using higher order sliding-mode observer for robot manipulators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ma, Z.; Sheng, X.; Zhu, X. Centimeter-level aerial assembly achieved with manipulating condition inference and compliance. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Jin, L.; Luo, X. Kinematics-based motion-force control for redundant manipulators with quaternion control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Jin, L.; Xie, Z.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y. Data-driven motion-force control scheme for redundant manipulators: A kinematic perspective. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5338–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kang, Y. Dynamic coupling switching control incorporating support vector machines for wheeled mobile manipulators with hybrid joints. Automatica 2010, 46, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lee, J. State control of a 12 DOF mobile manipulator via centroid feedback. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2013, 14, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korayem, M.H.; Nazemizadeh, M.; Rahimi, H.N. Trajectory optimization of nonholonomic mobile manipulators departing to a moving target amidst moving obstacles. Acta Mech. 2013, 224, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.; Wang, Y. Adaptive force/motion control system based on recurrent fuzzy wavelet CMAC neural networks for condenser cleaning crawler-type mobile manipulator robot. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Formation-based decentralized iterative learning cooperative impedance control for a team of robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefinia, E.; Talebi, H.A.; Doustmohammadi, A. A robust adaptive model reference impedance control of a robotic manipulator with actuator saturation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Adaptive fuzzy neural network command filtered impedance control of constrained robotic manipulators with disturbance observer. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 5171–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Li, X.; Song, S. Nonsingular terminal sliding-mode control of second-order systems subject to hybrid disturbances. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 5019–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kwon, W.; Park, P. An improved adaptive sliding mode control based on time-delay control for robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 10363–10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wu, Y.; Lv, X. Adaptive neural network control for full-state constrained robotic manipulator with actuator saturation and time-varying delays. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 3331–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hou, Z. Distributed model-free adaptive control for MIMO nonlinear multiagent systems under deception attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S. Fully distributed observer-based leader-following consensus of linear multiagent systems by adaptive dynamic event-triggered schemes. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Baldi, S.; Zhong, R. Leaderless consensus of heterogeneous multiple euler–lagrange systems with unknown disturbance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Mei, J.; Miao, Z.; Wu, A.; Ma, G. Fully distributed consensus of multiple euler–lagrange systems under switching directed graphs using only position measurements. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Z. Finite-time adaptive event-triggered control for robot manipulators with output constraints. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 3824–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Li, Z. Fast-exponential sliding mode control of robotic manipulator with super-twisting method. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, M.; Son, H. Robust predictor-based control for multirotor UAV with various time delays. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8151–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ju, Z. Attitude decoupling control of semifloating space robots using time-delay estimation and supertwisting control. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 4280–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Ju, F.; Chen, B. Time-delay control using a novel nonlinear adaptive law for accurate trajectory tracking of cable-driven robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 5234–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, F.; Sun, W.; Gu, J.; Yao, B. RBF-neural-network-based adaptive robust control for nonlinear bilateral teleoperation manipulators with uncertainty and time delay. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Niu, Y.; Lam, H. Event-triggered sliding mode control of fuzzy systems via artificial time-delay estimation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 2467–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, C.G.; Best, T.K.; Gregg, R.D. Improving sit/stand loading symmetry and timing through unified variable impedance control of a powered knee-ankle prosthesis. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 4146–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, T.K.; Welker, C.G.; Rouse, E.J.; Gregg, R.D. Data-driven variable impedance control of a powered knee–ankle prosthesis for adaptive speed and incline walking. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Chen, C.; Hu, H.; Fang, K.; Wu, X. Effect of hip assistance modes on metabolic cost of walking with a soft exoskeleton. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.F.N.; McGreavy, C.; Christou, A.; Vijayakumar, S. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance via online simulation of metabolic cost. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1410–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fiers, P.; Witte, K.A.; Jackson, R.W.; Poggensee, K.L.; Atkeson, C.G.; Collins, S.H. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance during walking. Science 2017, 356, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, N.J.; Krstić, M. PID tuning using extremum seeking: Online, model-free performance optimization. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2006, 26, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Divekar, N.V.; Thomas, G.C.; Gregg, R.D. Optimally biomimetic passivity-based control of a lower-limb exoskeleton over the primary activities of daily life. IEEE Open J. Control Syst. 2022, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Zwall, M.R.; Bolívar-Nieto, E.A.; Gregg, R.D.; Gans, N. Extremum seeking control for stiffness auto-tuning of a quasi-passive ankle exoskeleton. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 4604–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, P.; Oliveira, T.R.; Pino, A.V.; Fontana, A.P. Model-free neuromuscular electrical stimulation by stochastic extremum seeking. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 28, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijspeert, A.J. Central pattern generators for locomotion control in animals and robots: A review. Neural Netw. 2008, 21, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, A.; Ijspeert, A.J. Online optimization of swimming and crawling in an amphibious snake robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, G.; Nakanishi, J.; Morimoto, J.; Cheng, G. Experimental studies of a neural oscillator for biped locomotion with QRIO. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Torrealba, R.R.; Cappelletto, J.; Fermín, L.; Fernández-López, G.; Grieco, J.C. Cybernetic knee prosthesis: Application of an adaptive central pattern generator. Kybernetes 2012, 41, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Onal, C.D.; Fu, J. Reinforcement learning of CPG-regulated locomotion controller for a soft snake robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3382–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souzanchi-K., M.; Arab, A.; Akbarzadeh-T., M.R. Robust impedance control of uncertain mobile manipulators using time-delay compensation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 1942–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Notation | Variable | Notation | Variable | Notation | Variable | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inertia matrix | angle for joint 1 | amplitude | positive gain | ||||

| centripetal coriolis matrix | angle for joint 2 | constant | positive gain | ||||

| gravitational torque | gravity | total offset | positive gain | ||||

| real angle of joints | desired trajectory | raw trajectory | positive gain | ||||

| control torque | the i-th joint of | gait cycle | candidate function | ||||

| interaction torque | offset | cost function | candidate function | ||||

| reference trajectory | amplitude | weight | candidate function | ||||

| stiffness matric | frequency | assistant variable | control gain | ||||

| damping matric | time | constant matrix | control gain | ||||

| initial value | phase | constant gain | control gain | ||||

| impedance vector | constant | gain matrix | gain matrix | ||||

| seeking signal | frequency | estimation |

| Part | Mass (Kg) | Motion Range (°) |

|---|---|---|

| body structure | 2.06 | |

| control assembly | 2.38 | |

| joint 1 | 2.77 | −90° to 90° |

| joint 2 | 2.59 | −150° to 150° |

| total | 10.8 |

| Controllers | Tracking Error (°) MEAN (°) | MSE (°) | Force Error (N) MEAN (N) | MSE (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torque-based Control [10] | 4.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.3 |

| Voltage-based control [40] | 3.6 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Proposed control | 2.7 | 1.52 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pi, M. Collaborative Control for a Robot Manipulator via Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method and Extremum Seeking Optimization. Sensors 2025, 25, 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247648

Pi M. Collaborative Control for a Robot Manipulator via Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method and Extremum Seeking Optimization. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247648

Chicago/Turabian StylePi, Ming. 2025. "Collaborative Control for a Robot Manipulator via Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method and Extremum Seeking Optimization" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247648

APA StylePi, M. (2025). Collaborative Control for a Robot Manipulator via Interaction-Force-Based Impedance Method and Extremum Seeking Optimization. Sensors, 25(24), 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247648