Outlier-Resistant Initial Alignment of DVL-Aided SINS Using Mahalanobis Distance

Abstract

1. Introduction

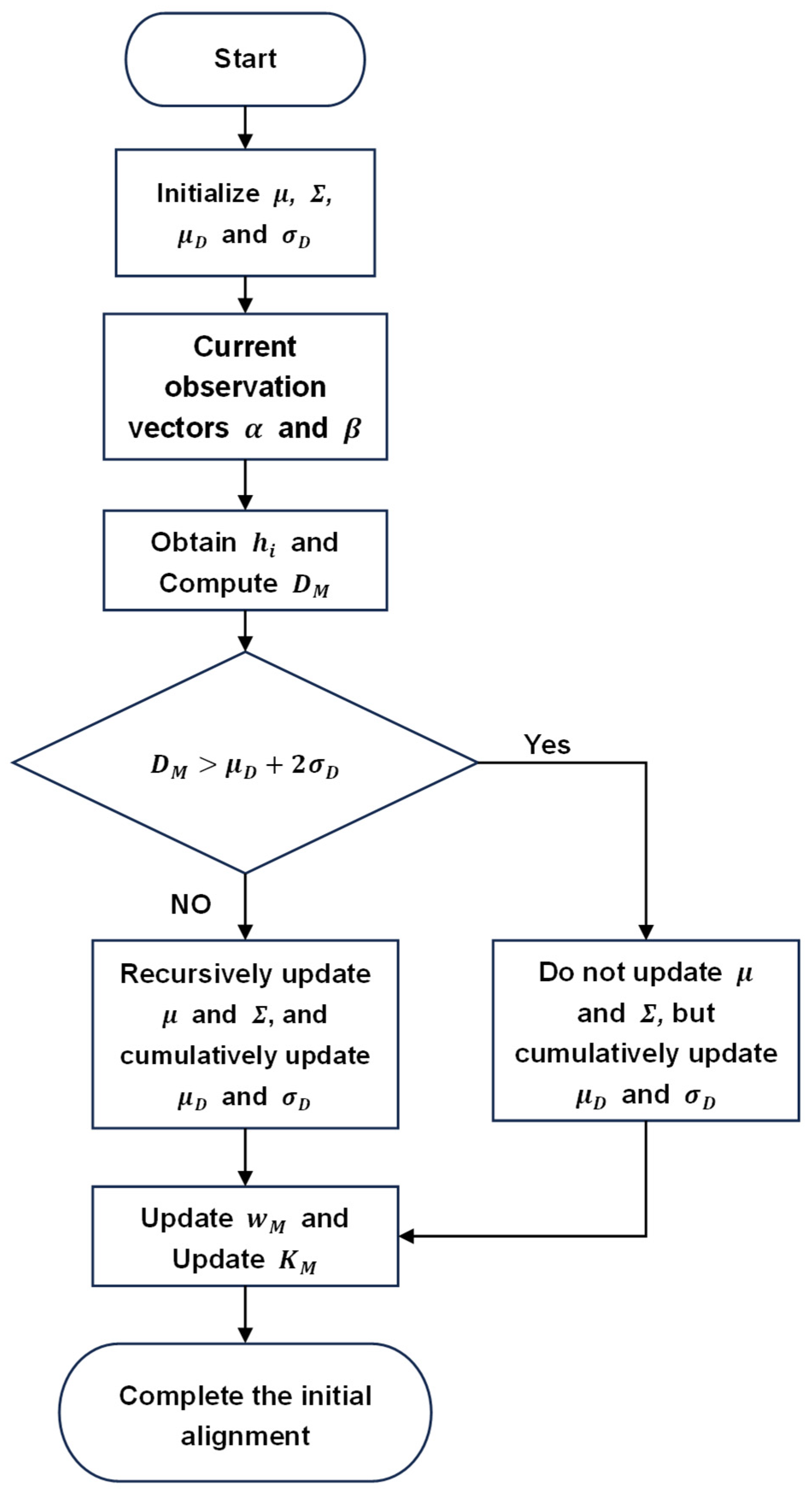

- A detection method was presented under the OBA framework and recursively calculates the Mahalanobis distance. By using historical statistics to adaptively set the anomaly detection threshold, it achieves real-time and statistically meaningful effective identification of outliers in the observed sequence.

- An exponential-type adaptive weighting function based on the detection mechanism was imported to realize the dynamic adjustment of the contribution of each historical epoch observation vector. This method overcomes a disadvantage that the traditional method depends on the fixed threshold value or static weight, so it can more effectively restrain outliers and interference.

- The article not only verifies algorithm performance under the fiducial simulation environment, but also establishes a time-varying anomaly model and some scenes of sea trial track, and assesses performances of the way under different interference and maneuvering degrees.

2. Problem Statement

3. An Initial Alignment Method with Interference Suppression Based on Mahalanobis Distance

4. Experimental Validation and Performance Analysis

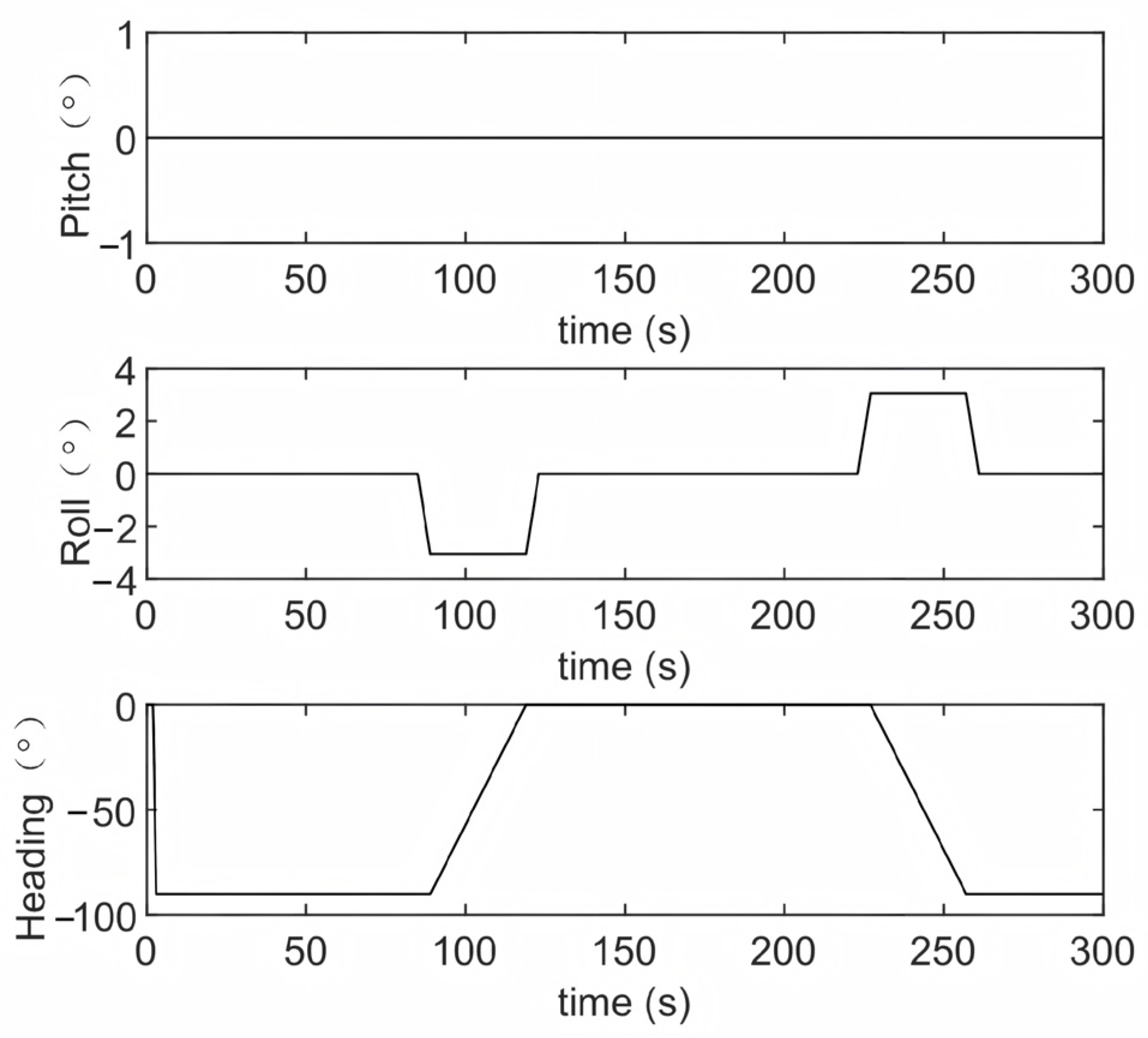

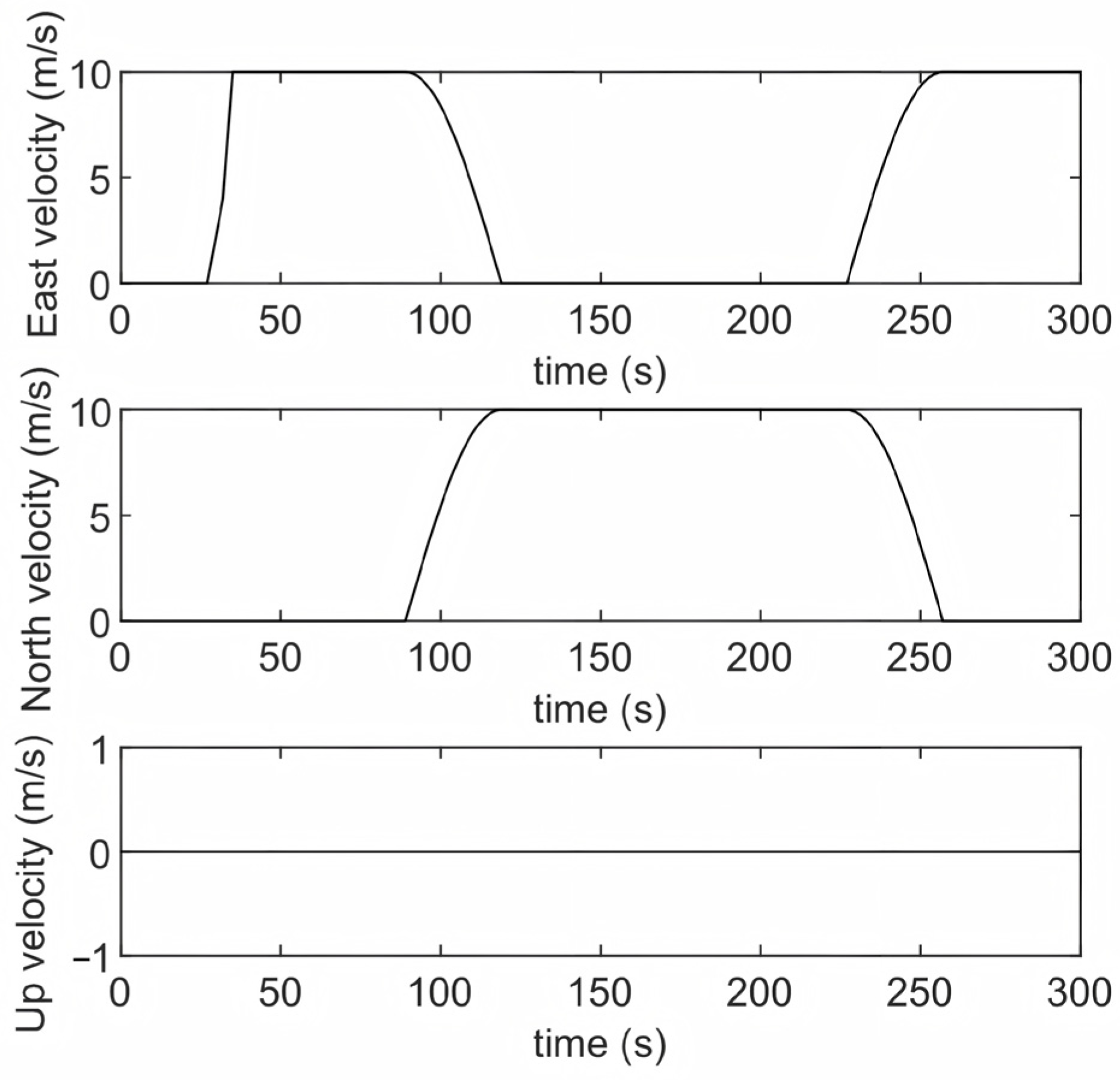

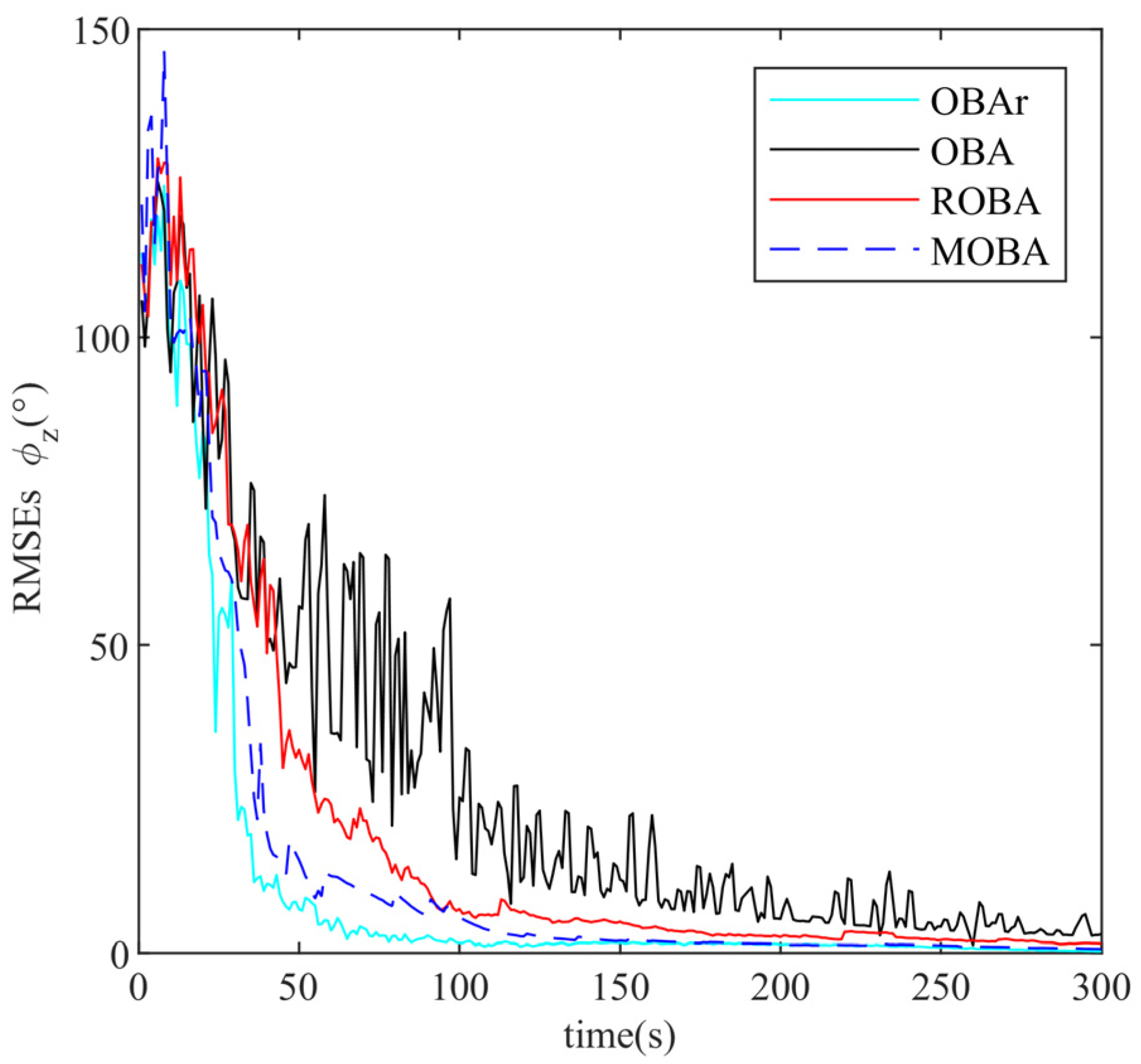

4.1. Simulation Experiments

4.1.1. The First Simulation

4.1.2. The Second Simulation

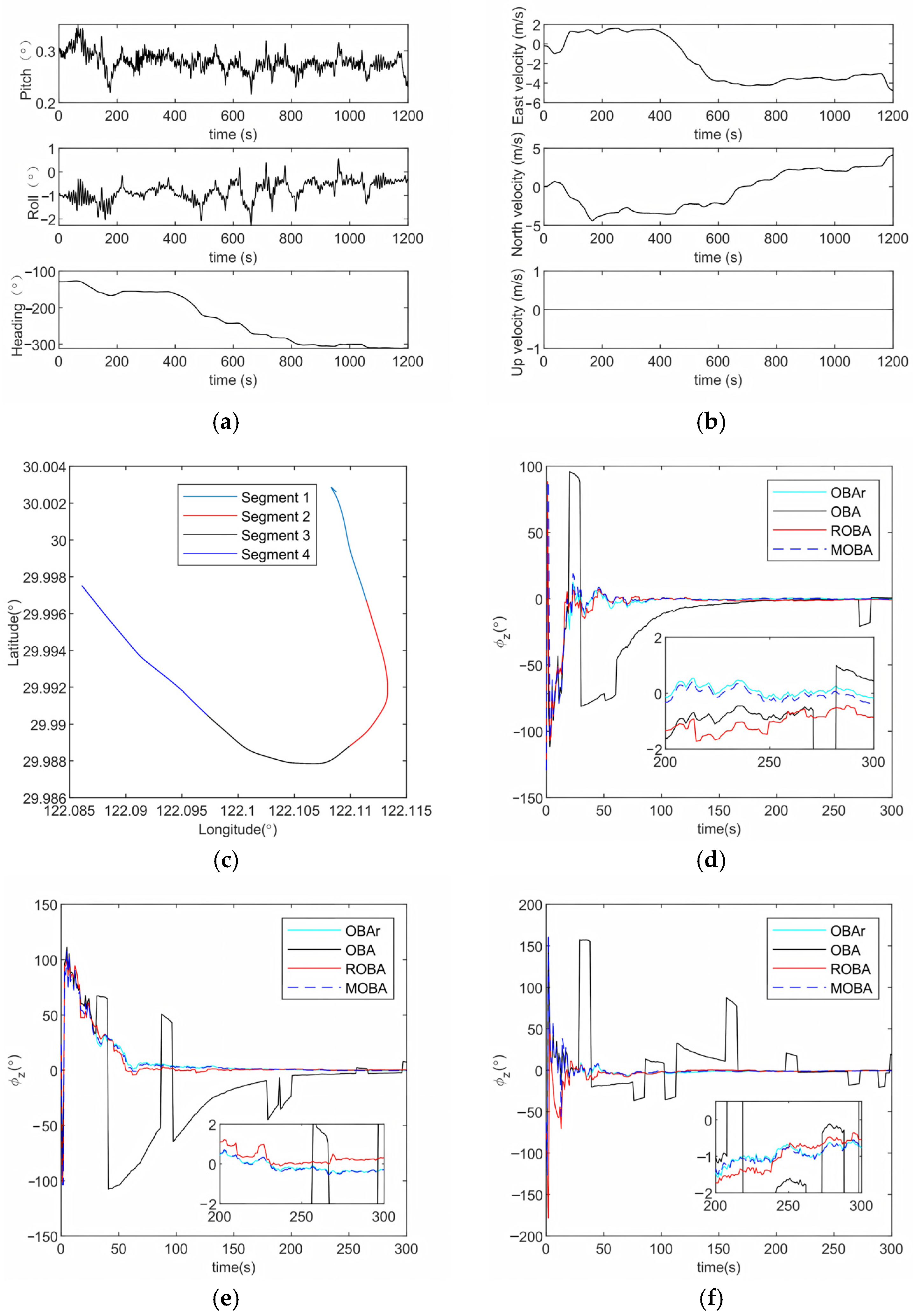

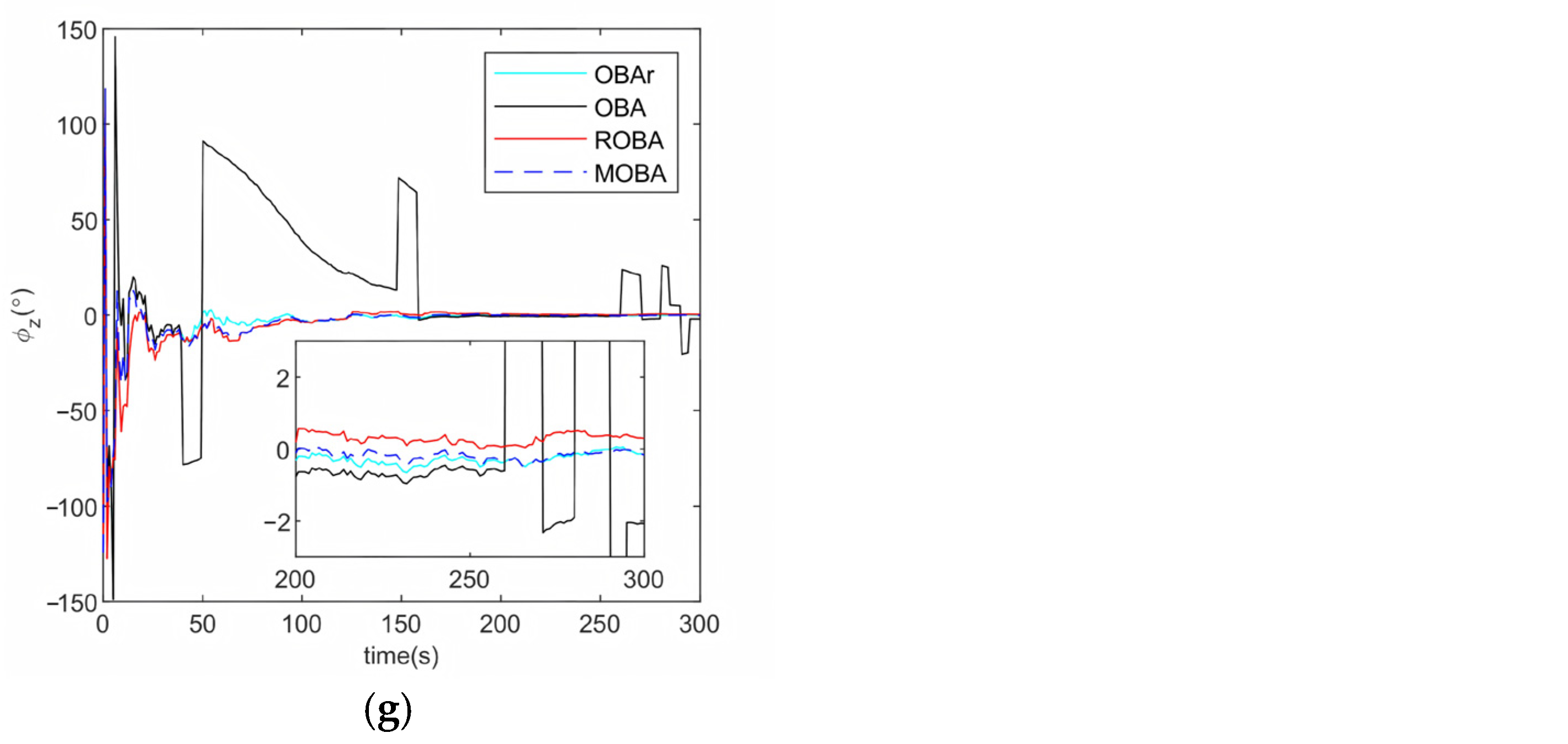

4.2. Field Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Notations | Definitions |

| Body frame | |

| Earth frame | |

| Inertial frame | |

| Navigation frame (geographic frame) | |

| Specific force in b-frame | |

| Gravity vector | |

| Body angular rate in b frame | |

| Ground velocity of SINS in b frame | |

| Attitude matrix from -frame to -frame | |

| Attitude matrix from body frame to navigation frame at time | |

| Value of the variable at time | |

| Angular velocity of -frame with respect to -frame projected in -frame | |

| Skew-symmetric matrix of the angular velocity of the inertial frame with respect to the navigation frame, projected in n-frame, i.e., the cross-product operator satisfying | |

| Skew-symmetric matrix of the angular velocity of the inertial frame with respect to the body frame, expressed in the b-frame, i.e., the cross-product operator satisfying for any vector . |

Appendix A

References

- Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z. In-motion filter-QUEST alignment for strapdown inertial navigation systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 1979–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Z. In-motion coarse alignment method based on reconstructed observation vectors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2017, 88, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pan, X. Velocity/position integration formula—Part I: Application to in-flight coarse alignment. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2013, 49, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yan, G.; Gu, D.; Zheng, J. Clever way of SINS coarse alignment despite rocking ship. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 2005, 23, 681–684. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F. Improved Kalman filter for SINS coarse alignment based on parameter identification. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2016, 24, 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Hu, X.; Wu, Z. Observability of initial alignment for strapdown inertial navigation systems. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2009, 45, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fang, J.; Du, M. Error analysis and gyro-bias calibration of analytic coarse alignment for airborne POS. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 3058–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. An initial alignment method for strapdown gyrocompass based on gravitational apparent motion in inertial frame. Measurement 2014, 55, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Song, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L. A novel self-alignment method for SINS based on three vectors of gravitational apparent motion in inertial frame. Measurement 2015, 62, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y. Gravitational apparent motion-based SINS self-alignment method for underwater vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 11402–11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Gradient descent optimizationbased self-alignment method for stationary SINS. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 3278–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Tong, J.; Li, Y. A fast SINS self-alignment method under geographic latitude uncertainty. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 2885–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Gui, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, T. A fast robust in-motion alignment method for SINS with DVL aided. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 3816–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pan, X. Velocity/position integration formula—Part II: Application to strapdown inertial navigation computation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2013, 49, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z.F.; Aggarwal, P.; Niu, X.; El-Sheimy, N. Civilian vehicle navigation: Required alignment of the inertial sensors for acceptable navigation accuracies. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2008, 57, 3402–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Jin, B.; Li, Y. Application of improved fifth-degree cubature Kalman filter in the nonlinear initial alignment of strapdown inertial navigation system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2019, 90, 095001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, D. Optimization-based alignment for inertial navigation systems: Theory and algorithm. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2011, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, Y.; Xue, B. Initial alignment for a Doppler velocity log-aided strapdown inertial navigation system with limited information. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; He, H.; Qin, F. In-Motion Initial Alignment for Odometer-Aided Strapdown Inertial Navigation System Based on Attitude Estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, J.; Li, K. Optimization-based alignment for strapdown inertial navigation system: Comparison and extension. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2016, 52, 1697–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Niu, X. Velocity-based optimizationbased alignment (VBOBA) of low-end MEMS IMU/GNSS for low dynamic applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 5527–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Qin, F.; Li, A. A novel backtracking scheme for attitude determination-based initial alignment. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Hu, B.; Li, Y. Backtracking integration for fast attitude determination-based initial alignment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 64, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, Z.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, T. Robust initial alignment for SINS/DVL based on reconstructed observation vectors. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gui, J.; Sun, Y.; Yao, Y. A robust in-motion alignment method based on DVL. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, T. A Robust In-Motion Optimization-Based Alignment for SINS/GPS Integration. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 4362–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Durovic, Z.M.; Kovacevic, B.D. Robust estimation with unknown noise statistics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1999, 44, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gui, J.; Sun, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, T. A Robust In-Motion Alignment Method With Inertial Sensors and Doppler Velocity Log. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 8500413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yuan, S.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Xu, J. DVL Aided SINS Coarse Alignment Solution with High Dynamics. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 155655–155666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| IMU | Sampling frequency | 100 Hz |

| Gyroscope bias | 0.01°/h | |

| Gyroscope noise | ||

| Accelerometer bias | 100 μg | |

| Accelerometer noise | ||

| DVL | Sampling frequency | 5 Hz |

| Velocity noise standard deviation | 0.05 m/s | |

| Outlier probability | random noise amplified ×200 2% |

| Error Type | OBAr | OBA | ROBA | MOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch | 0.005° | 0.04° | 0.017° | 0.009° |

| Roll | 0.006° | 0.011° | 0.008° | 0.006° |

| Heading | 0.57° | 4.39° | 1.85° | 0.89° |

| Segment | Duration (s) | Probability p | Magnitude mag |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–60 | 0.001 | 10 |

| 2 | 60–120 | 0.010 | 50 |

| 3 | 120–180 | 0.015 | 100 |

| 4 | 180–240 | 0.020 | 150 |

| 5 | 240–300 | 0.020 | 200 |

| Error Type | OBAr | OBA | ROBA | MOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch | 0.005° | 0.04° | 0.02° | 0.001° |

| Roll | 0.006° | 0.012° | 0.007° | 0.011° |

| Heading | 0.64° | 4.36° | 1.79° | 0.92° |

| Sensor | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| IMU | Sampling frequency | 98 Hz |

| Gyroscope bias stability | 0.01°/h | |

| Gyroscope angle random walk | ||

| Accelerometer bias stability | 100 μg | |

| Accelerometer velocity random walk | ||

| DVL | Sampling frequency | 1 Hz |

| Standard deviation of velocity measurement noise | 0.1 m/s | |

| Outlier probability | probability of 2% |

| Segment | OBAr | OBA | ROBA | MOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1160° | 8.7566° | 0.7660° | 0.2001° |

| 2 | 0.3416° | 3.2290° | 0.2102° | 0.3725° |

| 3 | 0. 8062° | 11.1331° | 0.6311° | 0.8092° |

| 4 | 0.2623° | 13.7160° | 0.3188° | 0.2727° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, T.; Luo, L.; Guo, J.; Wang, S. Outlier-Resistant Initial Alignment of DVL-Aided SINS Using Mahalanobis Distance. Sensors 2025, 25, 7599. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247599

Shen Y, Luo L, Wang G, Liu T, Luo L, Guo J, Wang S. Outlier-Resistant Initial Alignment of DVL-Aided SINS Using Mahalanobis Distance. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7599. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247599

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Yidong, Li Luo, Guoqing Wang, Tao Liu, Lin Luo, Jiaxi Guo, and Shuangshuang Wang. 2025. "Outlier-Resistant Initial Alignment of DVL-Aided SINS Using Mahalanobis Distance" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7599. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247599

APA StyleShen, Y., Luo, L., Wang, G., Liu, T., Luo, L., Guo, J., & Wang, S. (2025). Outlier-Resistant Initial Alignment of DVL-Aided SINS Using Mahalanobis Distance. Sensors, 25(24), 7599. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247599