Trajectories of Adherence to Study-Prescribed Physical Activity Goals in a mHealth Weight Loss Intervention

Highlights

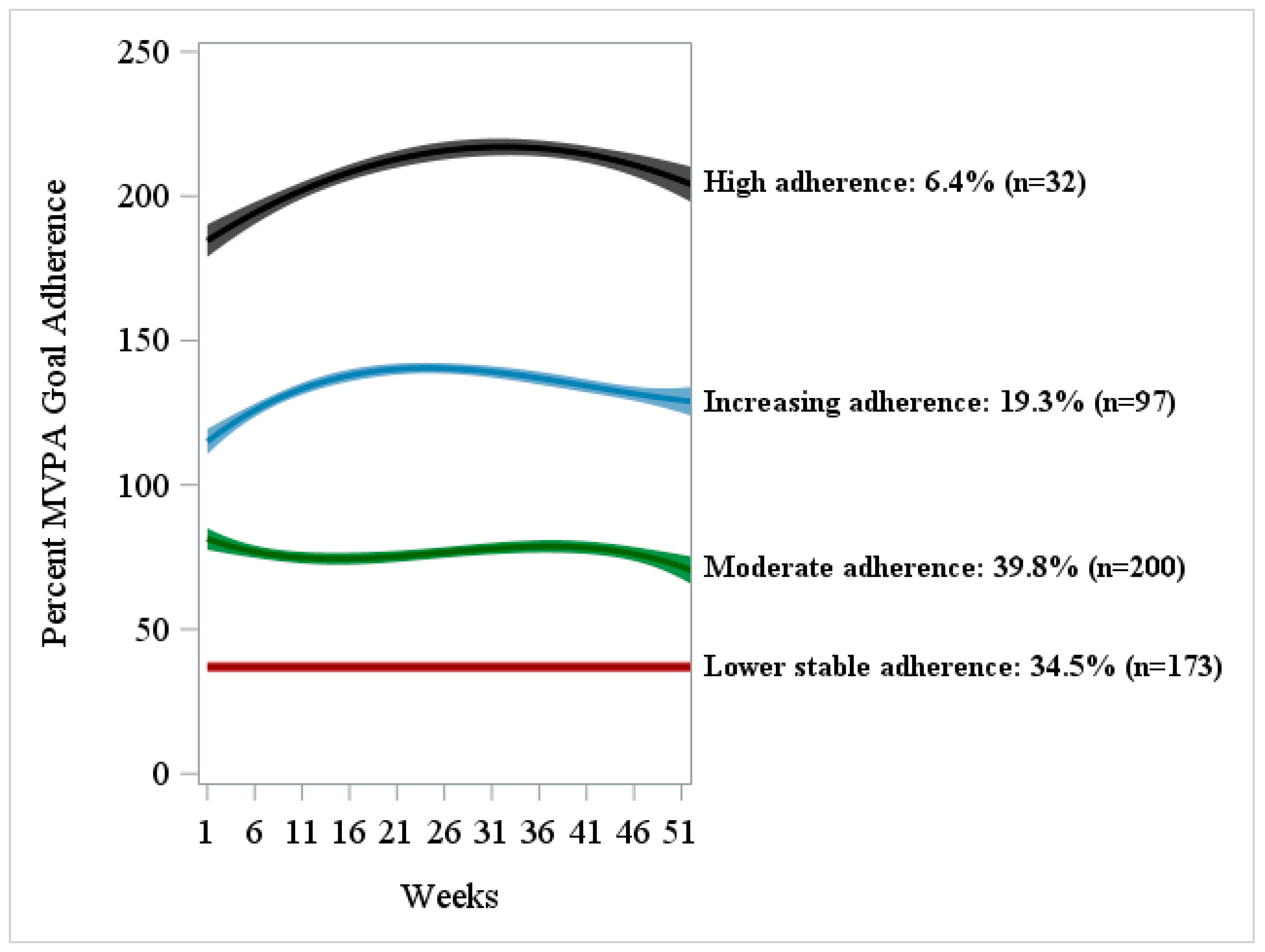

- Four distinct physical activity goal-adherence trajectories were identified in adults with overweight/obesity.

- Higher physical activity goal adherence was associated with greater weight loss.

- Early monitoring of physical activity adherence can identify individuals at risk of not meeting behavioral goals and allow timely, targeted support.

- Older adults and men may respond more positively to remotely delivered mHealth interventions using wearable activity trackers.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight, 7 May 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Emmerich, S.; Fryar, C.; Stierman, B.; Ogden, C.L. Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. NCHS Data Brief, 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, R.P.; Bemelmans, W.J.E.; Hoogenveen, R.T.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Woodward, M.; Knekt, P.; van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B.; Visscher, T.L.S.; Menotti, A.; et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: A meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300,000 persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C.; Rotnitzky, A.; Manson, J.E. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995, 122, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Blair, S.N.; Jakicic, J.M.; Manore, M.M.; Rankin, J.W.; Smith, B.K.; American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, E.L.; Patnode, C.D.; Webber, E.M.; Redmond, N.; Rushkin, M.; O’Connor, E.A. Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Weight Loss Interventions to Prevent Obesity-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Adults: An Updated Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018, 320, 1172–1191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oppert, J.-M.; Ciangura, C.; Bellicha, A. Physical activity and exercise for weight loss and maintenance in people living with obesity. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Soltani, S.; Emadi, A.; Zargar, M.S.; Najafi, A. Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2452185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgaddal, N.; Kramarow, E.A.; Reuben, C. Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief 2022, 443, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwood, K.-J.; Watson, G.; O’BRien, J.; Williams, A.D. Consumer-Based Wearable Activity Trackers Increase Physical Activity Participation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Davis, K.K.; Rogers, R.J.; King, W.C.; Marcus, M.D.; Helsel, D.; Rickman, A.D.; Wahed, A.S.; Belle, S.H. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss: The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Haaland, B.A.; Bilger, M.; Sahasranaman, A.; Sloan, R.; Nang, E.E.K.; Evenson, K.R. Effectiveness of activity trackers with and without incentives to increase physical activity (TRIPPA): A randomized controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Adeniji, C.; Van Marwijk, H.; McMillian, B.; Bower, P.; Panagioti, M. Interventions Using Wearable Physical Activity Trackers Among Adults With Cardiometabolic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2116382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Fu, C.; Hu, D.; Wei, Q. Wearable Activity Tracker-Based Interventions for Physical Activity, Body Composition, and Physical Function Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecher, C.; Pfisterer, B.; Harden, S.M.; Epstein, D.; Hirschmann, J.M.; Wunsch, K.; Buman, M.P. Assessing the Pragmatic Nature of Mobile Health Interventions Promoting Physical Activity: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e43162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D.S.; Odgers, C.L. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imes, C.C.; Zheng, Y.; Mendez, D.D.; Rockette-Wagner, B.J.; Mattos, M.K.; Goode, R.W.; Sereika, S.M.; Burke, L.E. Group-Based Trajectory Analysis of Physical Activity Change in a US Weight Loss Intervention. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Miki, T.; Shimizu, K.; Kanai, M.; Hagiwara, Y. Trajectories of Physical Activity During a 6-Month Mobile App-Based Lifestyle Modification Intervention in Physically Inactive Adults With Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, e70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringeval, M.; Wagner, G.; Denford, J.; Paré, G.; Kitsiou, S. Fitbit-Based Interventions for Healthy Lifestyle Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, E.M.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Delahanty, L.M.; Mele, L.; A Hoskin, M.; Edelstein, S.L. Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puciato, D.; Rozpara, M. Physical activity and socio-economic status of single and married urban adults: A cross-sectional study. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, Y.; Miao, H.; Sharma, K.; Li, C.; Yin, Z.; Brimhall, B.; Wang, J. Understanding Heterogeneity in Individual Responses to Digital Lifestyle Intervention Through Self-Monitoring Adherence Trajectories in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: Secondary Analysis of a 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unick, J.L.; Walkup, M.P.; Miller, M.E.; Apolzan, J.W.; Brubaker, P.H.; Coday, M.; Hill, J.O.; Jakicic, J.M.; Middelbeek, R.J.; West, D.; et al. Early Physical Activity Adoption Predicts Longer-Term Physical Activity Among Individuals Inactive at Baseline. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, L.E.; Sereika, S.M.; Parmanto, B.; Beatrice, B.; Cajita, M.; Loar, I.; Pulantara, I.W.; Wang, Y.; Kariuki, J.; Yu, Y.; et al. The SMARTER Trial: Design of a trial testing tailored mHealth feedback to impact self-monitoring of diet, physical activity, and weight. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 91, 105958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, L.E.; Sereika, S.M.; Parmanto, B.; Bizhanova, Z.; Kariuki, J.K.; Cheng, J.; Beatrice, B.; Loar, I.; Pulantara, I.W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Effect of tailored, daily feedback with lifestyle self-monitoring on weight loss: The SMARTER randomized clinical trial. Obesity 2022, 30, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleur, R.G.S.; George, S.M.S.; Leite, R.; Kobayashi, M.; Agosto, Y.; E Jake-Schoffman, D. Use of Fitbit Devices in Physical Activity Intervention Studies Across the Life Course: Narrative Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e23411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulantara, I.W.; Wang, Y.; E Burke, L.; Sereika, S.M.; Bizhanova, Z.; Kariuki, J.K.; Cheng, J.; Beatrice, B.; Loar, I.; Cedillo, M.; et al. Data Collection and Management of mHealth, Wearables, and Internet of Things in Digital Behavioral Health Interventions With the Awesome Data Acquisition Method (ADAM): Development of a Novel Informatics Architecture. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e50043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizhanova, Z.; Sereika, S.M.; Brooks, M.M.; Rockette-Wagner, B.; Kariuki, J.K.; Burke, L.E. Identifying Predictors of Adherence to the Physical Activity Goal: A Secondary Analysis of the SMARTER Weight Loss Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitabase. Fitbit Data Dictionary, Version 9. 19 August 2024. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/0ltkef2fmze1/45IN5bvBS827grKEsA8ZB0/648f3778acc936961f0572590c005ef0/Fitbit-Web-API-Data-Dictionary-Downloadable-Version-2.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; LaMonte, M.J.; Lee, I.-M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and Maintaining Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in Apparently Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.; Straiton, N.; Smith, S.; Neubeck, L.; Gallagher, R. Data management and wearables in older adults: A systematic review. Maturitas 2019, 124, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Ekelund, U.; Delisle Nyström, C.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Löf, M.; Labayen, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B. Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1821–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Sarwer, D.B.; Prus-Wisniewski, R.; Steinberg, C. Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: A randomized trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury, M.L.; Harvey, J.R.; A Krukowski, R.; A Pellegrini, C.; Wang, X.; West, D.S. Distinguishing early patterns of physical activity goal attainment and weight loss in online behavioral obesity treatment using latent class analysis. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.S.; Sackett, S.C. Psychosocial Variables Related to Why Women are Less Active than Men and Related Health Implications. Clin. Med. Insights Womens Health 2016, 9, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, A.D.; Santhanam, P.; Musani, S.K.; Ahima, R.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B. Metabolic Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Findings From the Look AHEAD Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e016947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crane, M.M.; Seburg, E.M.; Levy, R.L.; Jeffery, R.W.; Sherwood, N.E. Using targeting to recruit men and women of color into a behavioral weight loss trial. Trials 2020, 21, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rounds, T.; Harvey, J. Enrollment Challenges: Recruiting Men to Weight Loss Interventions. Am. J. Mens. Health 2019, 13, 1557988319832120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, D.; Packer, J.; Michalopoulou, S.; Cruz, J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M.; Mytton, O.T.; Russell, S.J. Assessing the evidence for health benefits of low-level weight loss: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T.L.; Swartz, A.M.; Cashin, S.E.; Strath, S.J. How many days of monitoring predict physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older adults? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.-L.K.; Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Frederiksen, P.; Horgan, G.; O’Driscoll, R.; Palmeira, A.L.; E Scott, S.; Stubbs, J.; Heitmann, B.L.; Larsen, S.C. Estimating physical activity and sedentary behaviour in a free-living environment: A comparative study between Fitbit Charge 2 and Actigraph GT3X. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|

| Age, years; mean ± SD | 45.0 ± 14.4 |

| Female; n (%) | 399 (79.5) |

| White; n (%) | 414 (82.5) |

| Married/partnered; n (%) | 329 (65.5) |

| Follow-up during the COVID-19; n (%) | 262 (52.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2; mean ± SD | 33.7 ± 4.0 |

| 12-mo PA messages opened for SM + FB, %; mean ± SD | 67.0 ± 32.5 |

| First week MVPA; minutes | |

| mean ± SD | 244.1 ± 171.9 |

| median [Q1, Q3] | 214 [118, 346] |

| Met ≥300 min/week during the first week; n (%) | 161 (32.1) |

| # | Trajectory Group Membership | Polynomial Order | Estimate ± SE | Estimated π 95% CI | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lower stable adherence, n = 173 (34.5%) | Intercept | 32.20 ± 0.73 | 0.34 0.30, 0.39 | 44.33 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | Moderate adherence, n = 200 (39.8%) | Intercept | 82.18 ± 1.87 | 0.40 0.36, 0.44 | 44.02 | <0.0001 |

| Linear | −1.29 ± 0.31 | −4.23 | <0.0001 | |||

| Quadratic | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 4.51 | <0.0001 | |||

| Cubic | −0.0008 ± 0.0002 | −4.60 | <0.0001 | |||

| 3 | Increasing adherence, n = 97 (19.3%) | Intercept | 112.38 ± 2.51 | 0.19 0.16, 0.23 | 44.78 | <0.0001 |

| Linear | 2.69 ± 0.41 | 6.48 | <0.0001 | |||

| Quadratic | −0.08 ± 0.02 | −4.26 | <0.0001 | |||

| Cubic | 0.0006 ± 0.0002 | 2.73 | 0.006 | |||

| 4 | High adherence, n = 32 (6.4%) | Intercept | 182.44 ± 3.10 | 0.06 0.04, 0.09 | 58.76 | <0.0001 |

| Linear | 2.14 ± 0.28 | 7.78 | <0.0001 | |||

| Quadratic | −0.03 ± 0.01 | −6.48 | <0.0001 | |||

| Sigma | 40.01 ± 0.20 | 198.87 | <0.0001 |

| # | Trajectory Group Membership | Predictors | Estimate ± SE | AOR (95% CI) | t-Value | p-Value | FDR Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lower stable adherence, n = 173 (34.5%) | Reference | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 2 | Moderate adherence, n =200 (39.8%) | Constant | −4.37 ± 0.83 | --- | −5.26 | <0.0001 | --- |

| Age, years | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 2.51 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

| Female vs. Male (reference) | −0.83 ± 0.46 | 0.44 (0.18–1.07) | −1.83 | 0.07 | 0.10 | ||

| Partnered vs. Single (reference) | −0.57 ± 0.31 | 0.57 (0.31–1.04) | −1.85 | 0.06 | 0.10 | ||

| First-week MVPA, minutes (square-root transformed) | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 1.57 (1.42–1.73) | 8.79 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Follow-up during COVID-19: Yes vs. No (reference) | −0.22 ± 0.28 | 0.80 (0.46–1.39) | −0.81 | 0.42 | 0.50 | ||

| SM + FB vs. SM (reference) | 0.18 ± 0.28 | 1.20 (0.69–2.07) | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.57 | ||

| 3 | Increasing adherence, n = 97 (19.3%) | Constant | −8.10 ± 1.10 | --- | −7.35 | <0.0001 | --- |

| Age, years | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 3.32 | 0.0009 | 0.004 | ||

| Female vs. Male (reference) | −1.37 ± 0.51 | 0.25 (0.09–0.69) | −2.69 | 0.007 | 0.02 | ||

| Partnered vs. Single (reference) | −1.11 ± 0.38 | 0.33 (0.16–0.69) | −2.95 | 0.003 | 0.01 | ||

| First-week MVPA, minutes (square-root transformed) | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 1.95 (1.70–2.24) | 10.24 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Follow-up during COVID-19: Yes vs. No (reference) | −0.72 ± 0.35 | 0.49 (0.25–0.97) | −2.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | ||

| SM + FB vs. SM (reference) | 0.41 ± 0.35 | 1.51 (0.76–2.99) | 1.17 | 0.24 | 0.31 | ||

| 4 | High adherence, n = 32 (6.4%) | Constant | −19.23 ± 2.30 | --- | −8.36 | <0.0001 | --- |

| Age, years | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 2.46 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

| Female vs. Male (reference) | −1.95 ± 0.70 | 0.14 (0.04–0.56) | −2.78 | 0.005 | 0.02 | ||

| Partnered vs. Single (reference) | −0.39 ± 0.64 | 0.68 (0.19–2.37) | −0.61 | 0.54 | 0.57 | ||

| First-week MVPA, minutes (square-root transformed) | 1.22 ± 0.12 | 3.39 (2.68–4.29) | 9.92 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Follow-up during COVID-19: Yes vs. No (reference) | −0.70 ± 0.58 | 0.50 (0.16–1.55) | −1.20 | 0.23 | 0.31 | ||

| SM + FB vs. SM (reference) | −0.01 ± 0.59 | 1.00 (0.31, 3.23) | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Full Sample (N)/ Completers Only (n) | Percent Weight Change (Full Sample, N = 502) Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | Cohen’s d | Percent Weight Change (Completers, n = 394) Mean (95% CI) | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower stable adherence n = 173/121 | −0.33 −1.41, 0.74 | 0.55 | reference | −1.87 −3.12, −0.62 | 0.003 | reference |

| Moderate adherence n = 200/157 | −2.59 −3.58, −1.59 | <0.0001 | 0.32 | −3.59 −4.68, −2.49 | <0.0001 | 0.26 |

| Increasing adherence n = 97/87 | −4.29 −5.73, −2.86 | <0.0001 | 0.55 | −4.77 −6.24, −3.30 | <0.0001 | 0.44 |

| High adherence n = 32/29 | −6.16 −8.66, −3.66 | <0.0001 | 0.71 | −6.82 −9.37, −4.27 | <0.0001 | 0.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bizhanova, Z.; Burke, L.E.; Brooks, M.M.; Rockette-Wagner, B.; Kariuki, J.K.; Sereika, S.M. Trajectories of Adherence to Study-Prescribed Physical Activity Goals in a mHealth Weight Loss Intervention. Sensors 2025, 25, 7595. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247595

Bizhanova Z, Burke LE, Brooks MM, Rockette-Wagner B, Kariuki JK, Sereika SM. Trajectories of Adherence to Study-Prescribed Physical Activity Goals in a mHealth Weight Loss Intervention. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7595. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247595

Chicago/Turabian StyleBizhanova, Zhadyra, Lora E. Burke, Maria M. Brooks, Bonny Rockette-Wagner, Jacob K. Kariuki, and Susan M. Sereika. 2025. "Trajectories of Adherence to Study-Prescribed Physical Activity Goals in a mHealth Weight Loss Intervention" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7595. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247595

APA StyleBizhanova, Z., Burke, L. E., Brooks, M. M., Rockette-Wagner, B., Kariuki, J. K., & Sereika, S. M. (2025). Trajectories of Adherence to Study-Prescribed Physical Activity Goals in a mHealth Weight Loss Intervention. Sensors, 25(24), 7595. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247595