Design and Simulation of Suspension Leveling System for Small Agricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

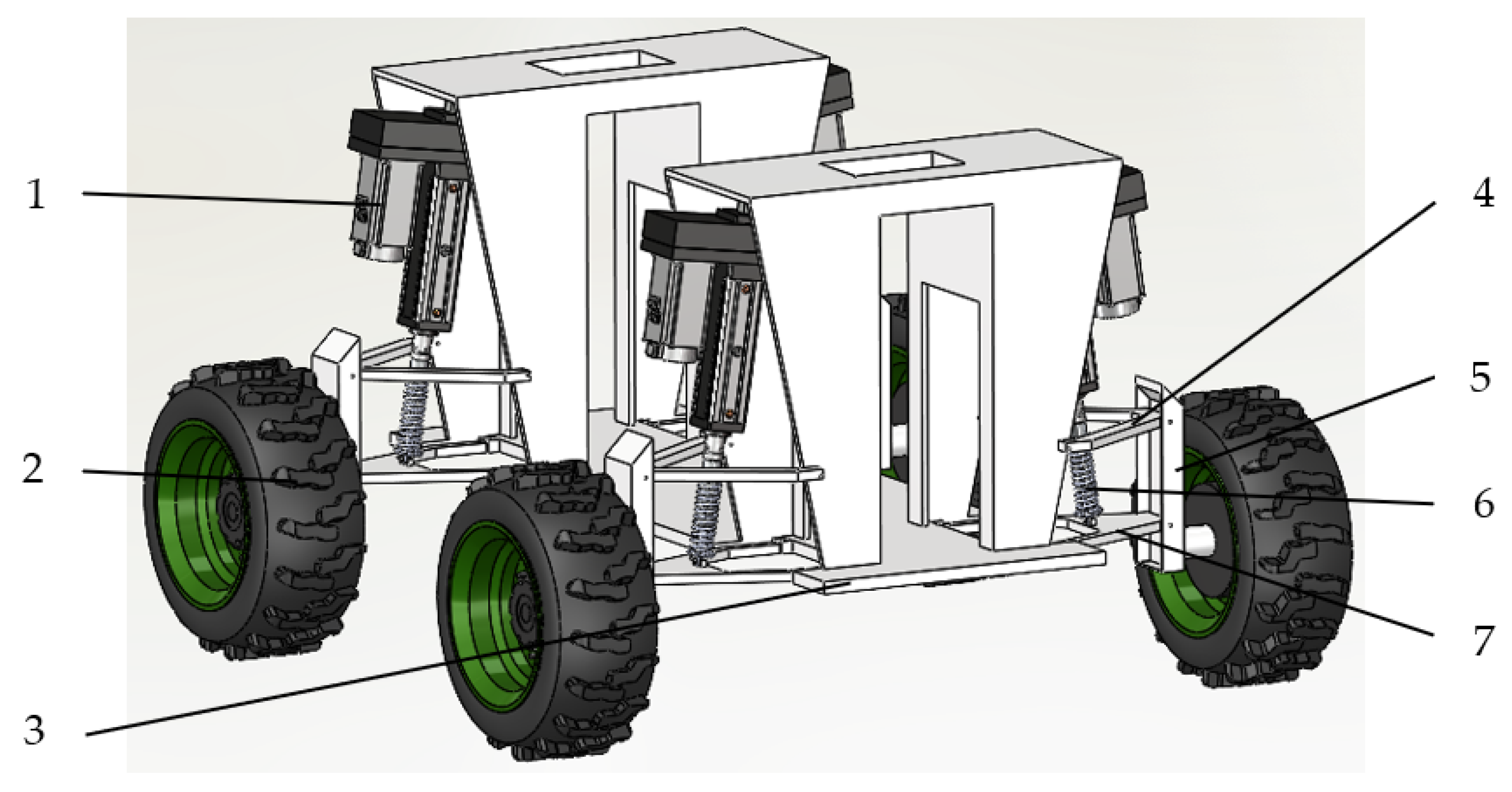

2. Levelling Control System and Key Executing Agencies

2.1. Levelling Control System

2.2. Key Executing Agencies

- (1)

- High transmission efficiency: Electric cylinders employing precision ball screws or planetary roller screws eliminate numerous complex mechanical structures, significantly enhancing transmission efficiency to exceed 90%. Conversely, hydraulic cylinders feature multiple energy conversion stages, with combined effects of fluid compression, flow resistance, leakage, and mechanical friction resulting in lower transmission efficiency, typically below 50% [26].

- (2)

- Rapid response speed: Electric cylinders offer adjustable linear operating speeds across a broad range, with stable low-speed performance. Hydraulic cylinders typically operate at speeds up to 35 mm/s, whereas standard electric cylinders can reach 55 mm/s. Models employing planetary roller screws achieve speeds as high as 2000 mm/s [26], demonstrating a pronounced velocity advantage.

- (3)

- High positioning accuracy: Servo electric cylinders achieve precise positioning of approximately 0.01 mm through servo control, demonstrating exceptional positioning accuracy [26]. Electric cylinders attain high positioning accuracy even in semi-closed-loop operation. Conversely, hydraulic cylinders, affected by factors such as fluid compressibility, leakage, temperature variations, and mechanical friction, require closed-loop control systems to achieve comparable positioning precision.

- (4)

- Simple structure, compact footprint, and convenient maintenance [27]: Electric cylinders primarily comprise a motor and a nut-screw mechanism, featuring straightforward construction and compact dimensions that minimise workspace requirements. Their simplicity facilitates rapid fault diagnosis during malfunctions and simplifies routine maintenance. In contrast, hydraulic cylinders necessitate periodic management of fluid contamination, replacement of hydraulic oil and seals, inspection for pipeline leaks and component wear, and rely on specialised operation to ensure system stability.

- (5)

- High reliability and safety [28]: Electric cylinders can incorporate advanced sensor systems and various stroke control devices to monitor and provide feedback on operational status, preventing accidents.

- (6)

- Stable operation and extended service life: Electric cylinders utilising ball screws or planetary roller screws significantly reduce friction in the transmission components, enhancing operational stability and prolonging service life.

- (7)

- Exceptional environmental adaptability: Electric cylinders exhibit minimal sensitivity to ambient temperatures, functioning reliably in extreme conditions including low/high temperatures, rain, and snow. In contrast, hydraulic cylinders are significantly affected by temperature variations, which alter hydraulic fluid viscosity, accelerate seal wear and leakage, and may compromise fluid compressibility, thereby disrupting pressure transmission and motion control precision.

3. Suspension Model Construction

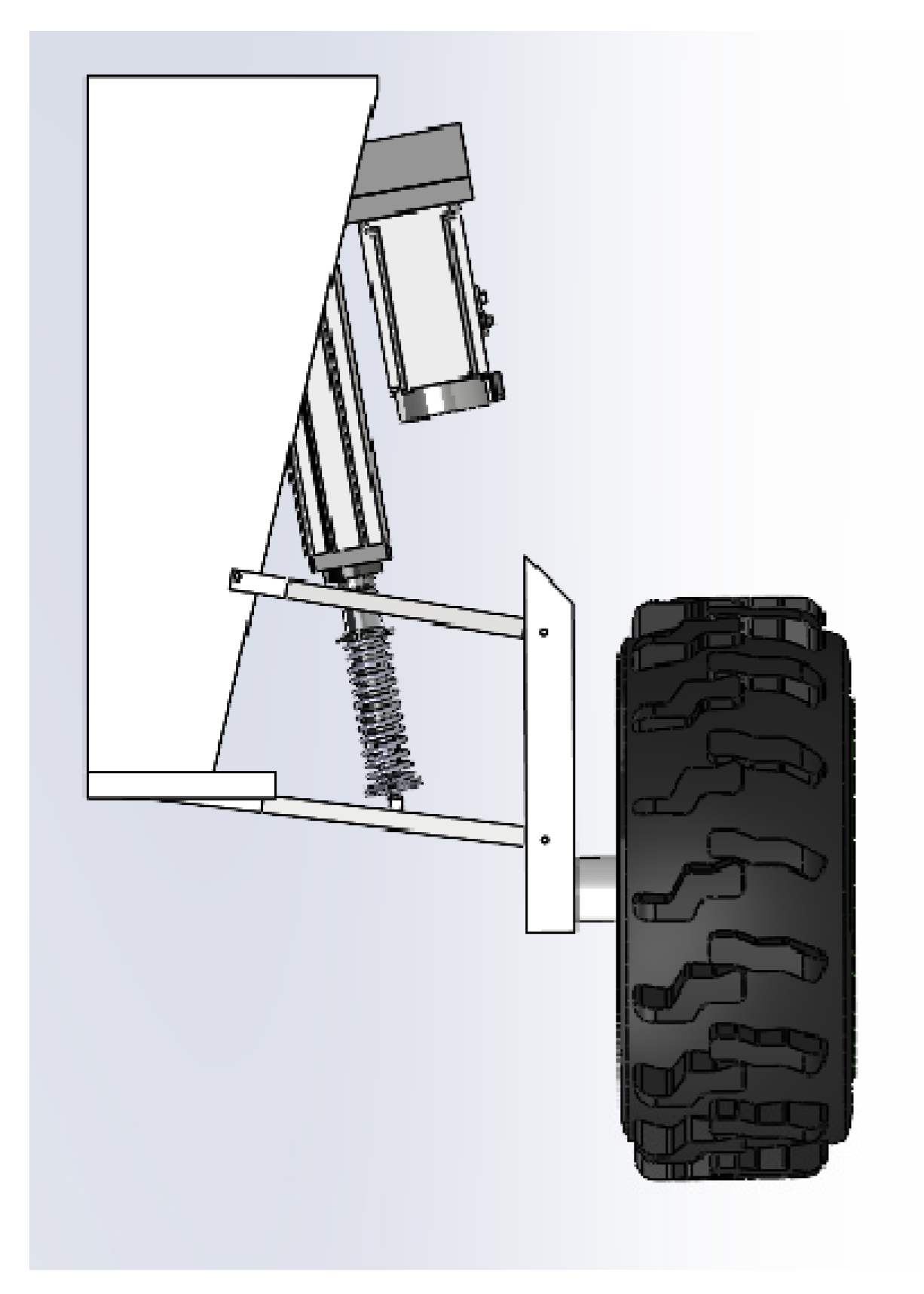

3.1. Kinematic Model

3.2. Dynamic Model

4. Fuzzy PID Controller

4.1. Principles of Fuzzy Control

4.2. Fuzzy PID Controller Design

- (1)

- The magnitude of |e| indicates the distance of the chassis height from the setpoint. When |e| is large and positive, the chassis height deviation is significant. To rapidly reduce this deviation, response speed should be increased by setting to a large positive value and to a large positive value. When |e| is moderately positive, to sustain a relatively rapid reduction in deviation, should be set to a small positive value and to zero. When |e| is small, should be set to a small positive value and to a small negative value. When |e| is zero, the tilt angle is close to the preset value. To completely eliminate deviation and reach the set value while preventing system overshoot and vibration, should be set to a small negative value and to a large negative value.

- (2)

- The magnitude of |ec| indicates the extent of non-uniform chassis height variation. When |ec| is large and positive, the chassis height may abruptly increase away from the preset value or rapidly decrease towards it. To suppress further deviation growth or prevent overshoot, is set to a large positive value. When |ec| is moderately positive, is set to a small positive value. When |ec| is zero, is set to a small negative value.

- (3)

- When |e| is large and positive and |ec| is small and positive, to achieve rapid response and swift deviation reduction, is set to a small positive value, while and are set to zero.

- (4)

- When |e| is small and positive while |ec| is large and positive, although |ec| is substantial, the chassis height remains near the setpoint range. To prevent overshoot, is set to a small negative value and to a small negative value. To suppress further increase in tilt angle, is set to a small positive value.

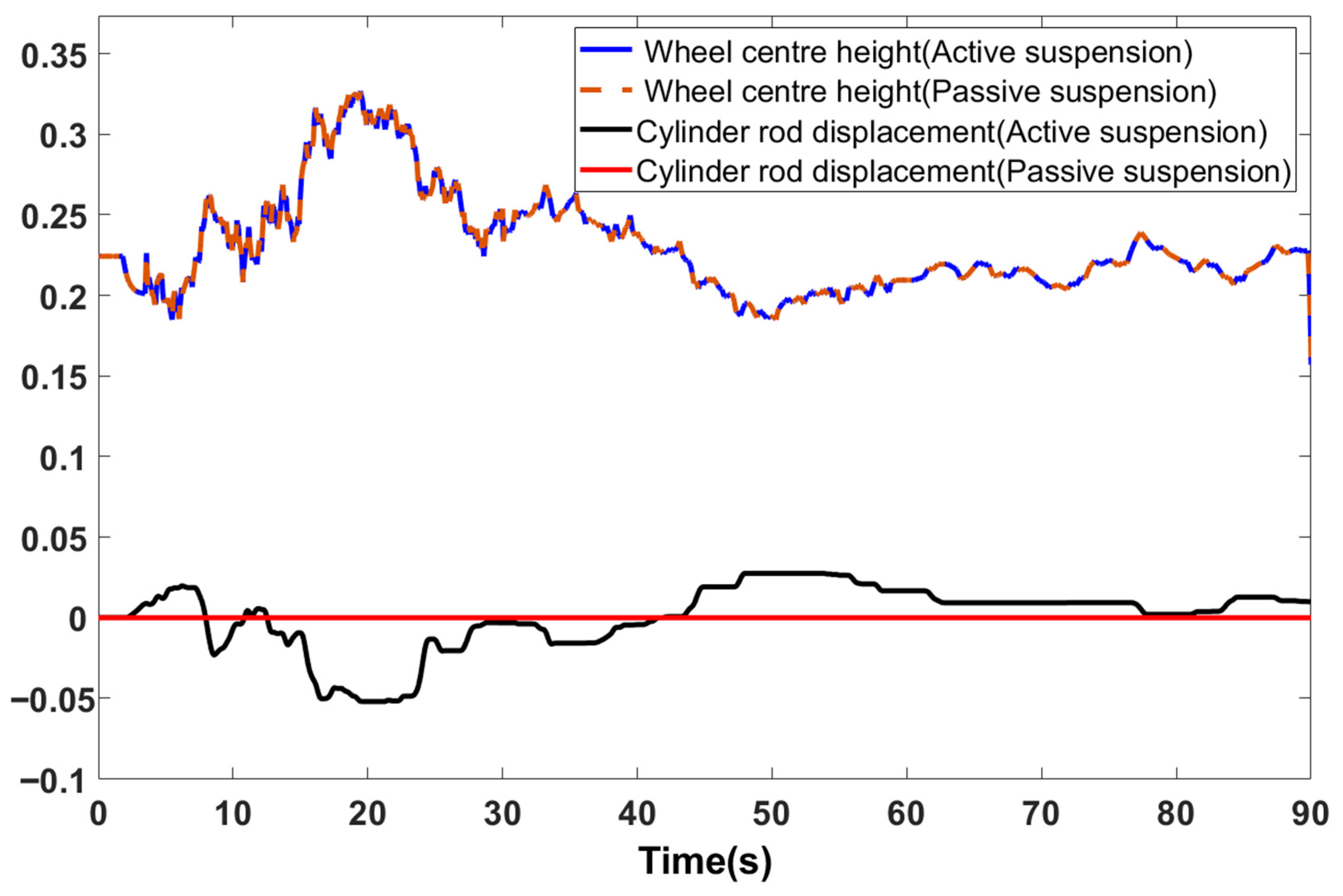

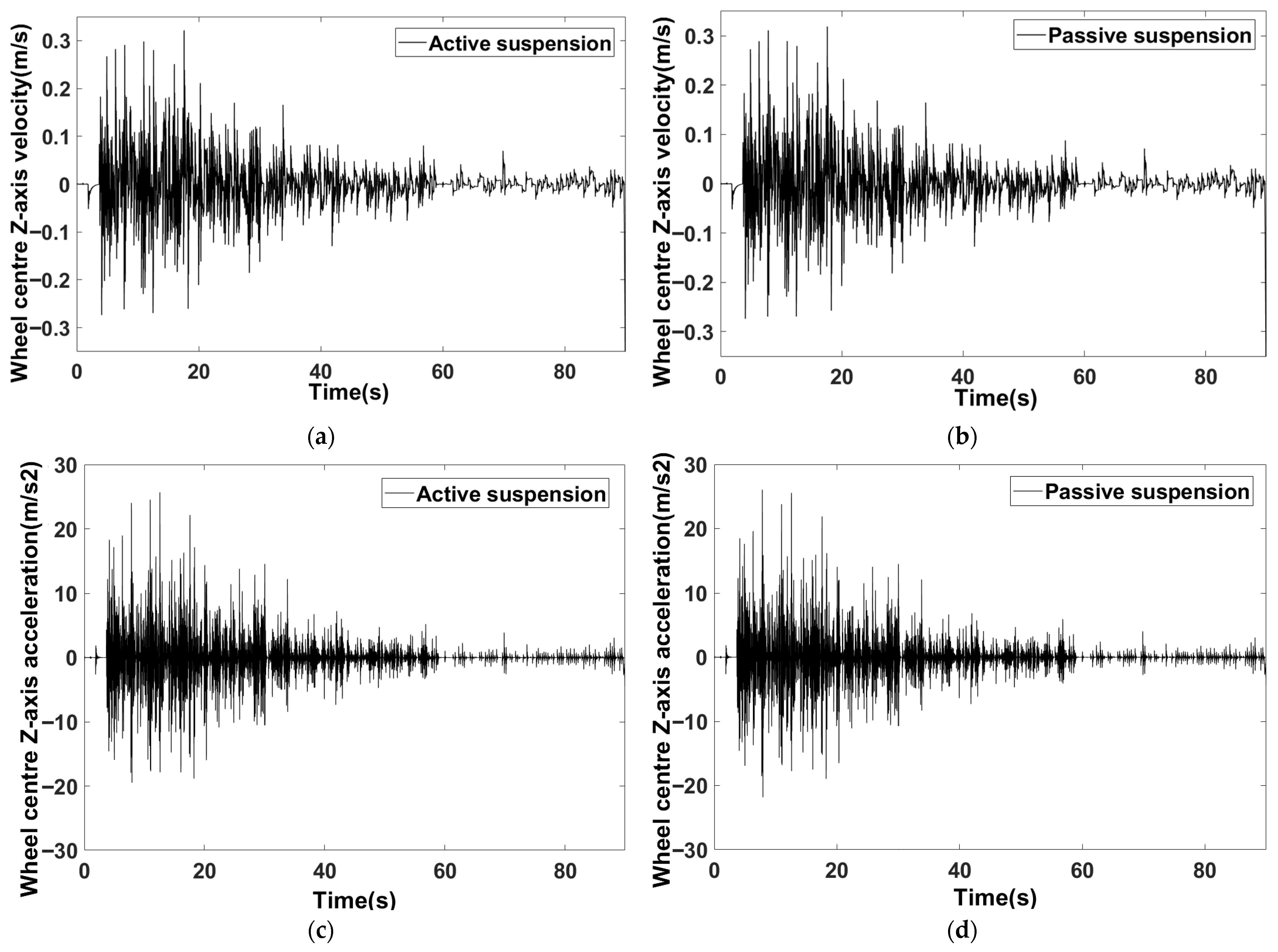

5. Control System Simulation Analysis

6. Discussion

- (1)

- Comparison with conventional hydraulic levelling systems: The transmission efficiency of the servo electric cylinder employed herein (≥90%) is nearly doubled compared to hydraulic cylinders (≤50%), thereby avoiding issues such as pipeline leakage in hydraulic systems, levelling lag caused by temperature-dependent oil viscosity, and suboptimal levelling precision. The system response time is ≤0.8 s, whereas hydraulic systems typically exhibit response times of 1.2–1.5 s, thereby enhancing overall system responsiveness. Moreover, electric cylinders dispense with complex components such as hydraulic pumps and reservoirs, offering reduced volume and mass compared to hydraulic systems, thereby better meeting the lightweight requirements of compact agricultural machinery.

- (2)

- Comparison with semi-active levelling or passive adaptation: Systems such as parallelogram-type semi-active levelling driven by hydraulic cylinders with passive contouring, or passive adaptation via bending and twisting mechanisms, cannot accommodate compound slopes. This study demonstrates that servo electric cylinders employing fuzzy PID control can regulate output parameters in response to road surface excitation, providing real-time adaptation to terrain variations. This capability enables adaptation to diverse operational conditions, offering valuable reference for omnidirectional levelling under compound slopes (roll + pitch).

- (1)

- The simplified tyre model neglects lateral dynamic coupling effects. The point-contact model accounts solely for vertical tyre stiffness and compression, disregarding lateral deflection forces and restoring moments under cross-slope conditions. During hilly terrain operations, substantial lateral forces induce chassis roll, causing single-side wheel deflection forces. Consequently, measured vertical suspension displacements deviate from actual road surface excitation, leading to compensation errors in the electric cylinder levelling system.

- (2)

- The quarter-suspension model disregards multi-wheel coupling effects. This study establishes dynamic equations solely for single-wheel suspension, neglecting load transfer across all four wheels during complex terrain conditions. For instance, when front wheels traverse pits, body pitching induces additional loads on rear suspension. In practical agricultural machinery operation, uneven multi-wheel load distribution causes electric cylinder thrust overshoot, potentially leading to structural damage during prolonged operation. The current model fails to simulate such multi-wheel coordination issues.

- (3)

- The road surface excitation model excludes unstructured terrain features. This paper generates random road surface excitation based on the ISO 8608 standard, omitting irregular disturbances common in hilly terrain such as protruding rocks, potholes, and subsidence in soft soil. Soft soil causes variations in tyre contact area.

- (1)

- Development of a multi-degree-of-freedom vehicle model: The quarter-suspension model will be expanded into a seven-degree-of-freedom vehicle model, incorporating three global degrees of freedom (vertical, roll, and pitch) and four independent vertical degrees of freedom for each wheel. Coupled dynamic equations will be derived from Lagrange’s equations to clarify the coupling relationships between pitch and roll. The Pacejka tyre model will be incorporated, inputting parameters such as camber angle, vertical load, and tyre pressure to output lateral forces, steering moments, and longitudinal adhesion. This addresses the limitations of the current point-contact model.

- (2)

- Multi-wheel Cooperative Control: The control algorithm employs a master-slave configuration. The master controller acquires the vehicle’s overall roll and pitch angles via dual-axis inclinometers. Integrating this with the full vehicle dynamics model, it calculates the coupled disturbance compensation required for each wheel. Concurrently, it dynamically adjusts weighting factors based on vertical load feedback from each wheel, preventing single-wheel overload. Each wheel suspension employs an independent slave controller executing fuzzy PID control. This tracks local target height while receiving coupled compensation values from the master controller, enabling real-time adjustment of electric cylinder extension/retraction.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- An active levelling system for small agricultural machinery chassis in hilly terrain was designed based on a fuzzy PID algorithm, proposing a ‘servo electric cylinder-spring-shock absorber series configuration’ solution. Kinematic and dynamic models were established based on the installation position and operational state of the electric cylinder within the quarter-link suspension. The kinematic model yielded the relationship between the vertical displacement of the electric cylinder’s support point and the extension length of its rod.

- (2)

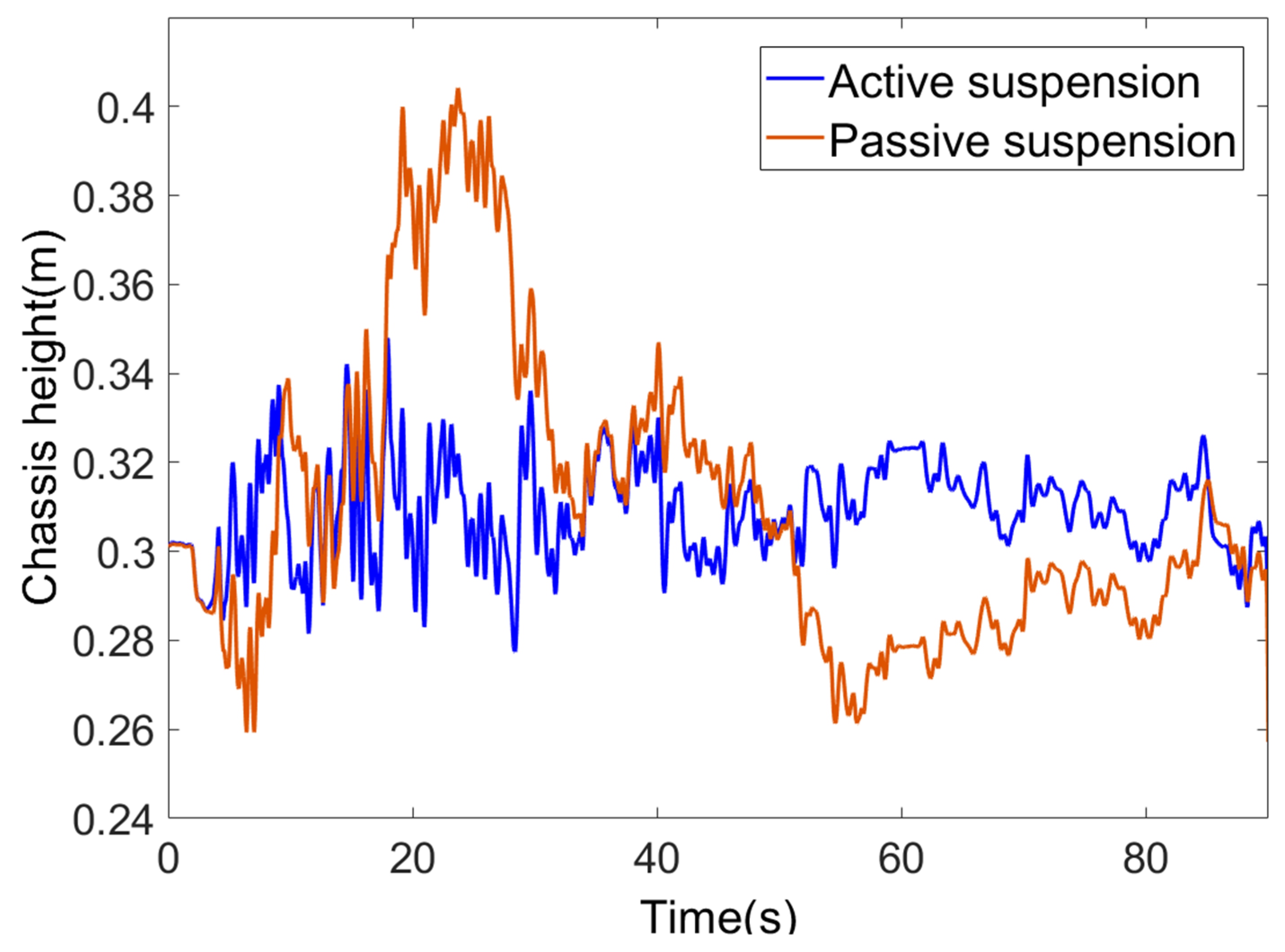

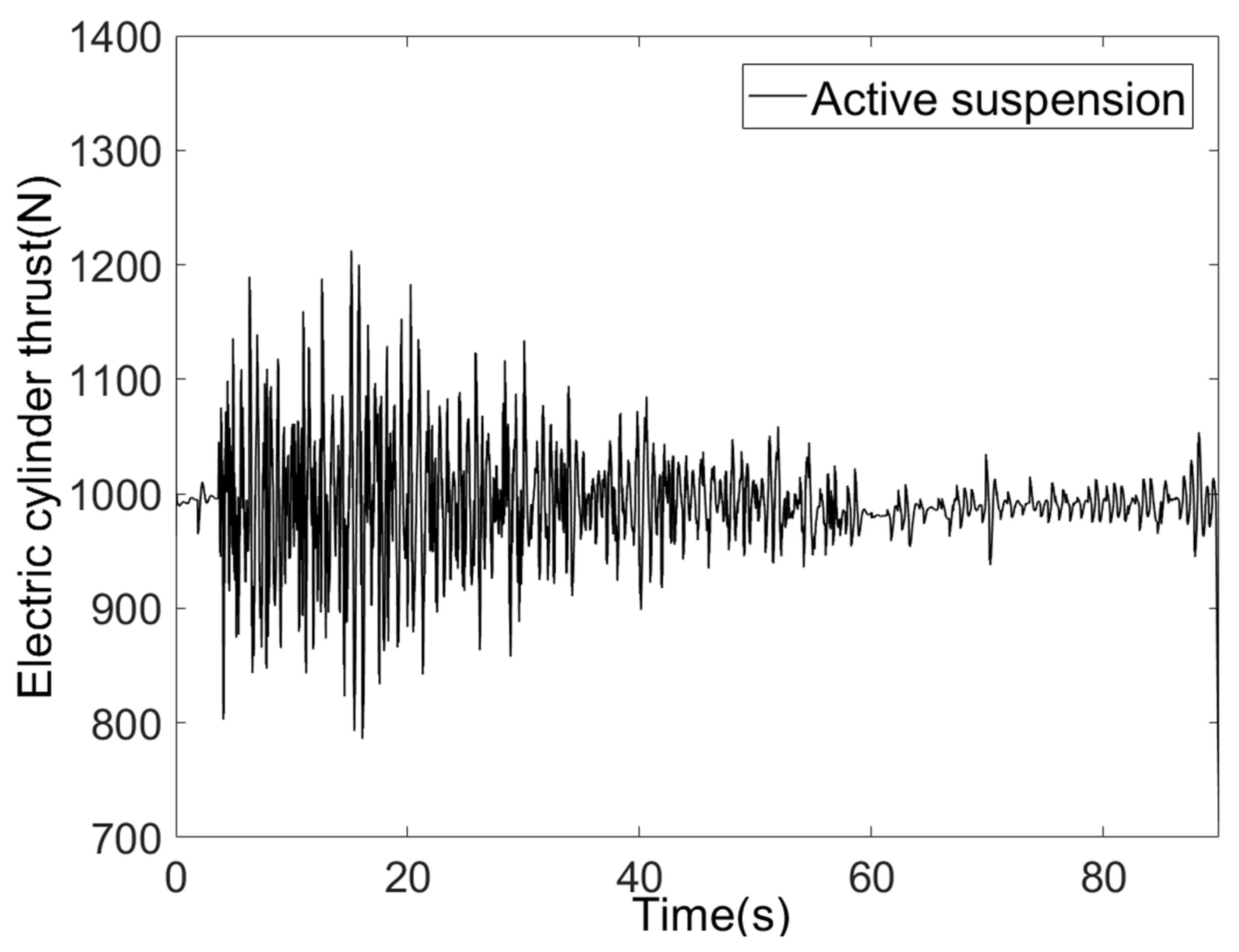

- A comparative simulation experiment was conducted between a passive suspension and an active suspension. The simulation results demonstrated that the active levelling system based on fuzzy PID control strictly confined the actual chassis height deviation to within ±0.05 m when traversing random road surfaces, representing a significant improvement in chassis stability compared to the passive suspension. The chassis height variation rate remained within ±0.2 m/s, demonstrating the shock absorption capabilities of the spring and damping components. The electric cylinder response time was ≤0.8 s, exhibiting rapid responsiveness.

- (3)

- This research provides agricultural machinery manufacturers with a lightweight, highly efficient, and low-complexity active levelling solution. Its simplified structural design and precise control logic can facilitate the development of compact agricultural machinery for hilly and mountainous terrains, thereby advancing the mechanisation of agriculture in such regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCU | Microcontroller Unit |

References

- Shao, T.; Wang, K. Path optimization of agricultural mechanization in hilly areas from “adapting to land conditions with machinery” to “farmland construction suitable for mechanization”. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2024, 45, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z. Evaluation of Mechanized Production Model Based on High Quality and High Efficiency in Southwest Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Leng, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, R.; Lv, X. Simulation and Experiment of the Smoothness Performance of an Electric Four-Wheeled Chassis in Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Exploration and Practice of Mechanical Integration of Soybean and Maize Belt Composite Planting. Agric. Technol. Equip. 2024, 172–173, 176. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTExNzE2MDExNxIQbmp0Z3lhcTIwMjQwODA2MhoId3p6OXAxNnk%3D (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, F.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Q.; Luo, P. Research review of agricultural equipment and slope operation key technologies in hilly and mountains region. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 1–18. Available online: https://www.nyjxxb.net/index.php/journal/article/view/1608 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Gao, M. Study on the Agricultural Machinery of Powered Chassisand Body Leveling Device of Hilly Mountainous. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Yang, F.; Xu, X. Design of Remote Control System for Hillside Crawler Micro-farming Tractor. Tract. Farm Transp. 2011, 38, 19–22. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=hQtzIo_70oGeFSkb_Y7Bq1G4rh46Jbc4D5z74Mmb3nAu8oqGXHiOhjrhPq3bND9LI8ZD42QzESEYr8ZmKTZL3Wz-hqkXnb3TJN5mbdcFiw-0JzMDrOIaw-jTi4EAeTXVshwNZgUj--fiyUOY66ZFimcr3w66lJfARsW38Ekm6AqSGvu-ihHBgA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Wang, T.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y. Design of body automatic leveling control system of hillside tractor. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2014, 36, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Research and Design of the Hillside Crawler Tractor Attitude Leveling Control System. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Design and Test of The Hillside Tractor Body Automatic Leveling Control System. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Meng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z. Design and physical model experiment of an attitude adjustment device for a crawler tractor in hilly and mountainous regions. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, Y. Design and test of transport vehicle for hillside orchards based on center of gravity regulation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 430–442. Available online: https://www.aeeisp.com/nyjxxb/en/article/id/dd562f9f-09e4-4a37-99f6-f27745d084cc (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Ning, P. Design and Test of Power and Longitudinal Adjustment Mechanism of Center of Gravity of Electric Tractor. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Ling, T. Recent Technical Structure Overview of Large and Medium sized Tractors in Europe and America. Tract. Farm Transp. 2002, 31–33+40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Sky-jump-V950 half-track tractor of BCS company. Tract. Farm Transp. 2019, 46, 8–10. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/Ch9QZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJTmV3UzIwMjUwMTE2MTYzNjE0EhJ0bGp5bnl5c2MyMDE5MDYwMDQaCGV4YnhwbDN5 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Bałchanowski, J. Mobile wheel-legged robot: Researching of suspension leveling system. In Advances in Mechanisms Design: Proceedings of TMM 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 8, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bałchanowski, J. Modelling and simulation studies on the mobile robot with self-leveling chassis. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2016, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ma, W.; Zhao, E.; Lu, X.; Feng, X. Design and physical model experiment of body leveling system for roller tractor in hilly and mountainous region. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 36–44. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20183327270 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Peng, H.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Huang, J.; Zhao, E. Control system of self-leveling in hilly tractor body through simulation and experiment. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2019, 49, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Li, Y.; Tao, J. Design and experiment of active attitude adjustment system for hilly area tractors. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qin, C.; Liu, C.; Yin, Y. Double closed loop fuzzy PID control method of tractor body leveling on hilly and mountainous areas. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 17–23+34. Available online: https://nyjxxb.net/index.php/journal/article/view/879 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Jia, X.; Shi, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, G.; Geng, D.; Lan, Y.; Wang, B. Design and Test of Automatic Leveling System for Chassis of SmallAgricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lv, X.; Yang, H.; Du, L.; Liu, Z.; Tang, P.; Lv, X. Design of leveling system for mountain tractor based on fuzzy PlD. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 49, 121–126. Available online: https://xb.hunau.edu.cn/hnndzr/article/abstract/2023010117?st=search (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Yang, H. Research on Auto Leveling Control System of Tractor Body in Hilly Area Based on Fuzzy PlD. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R.; Qi, X.; Chen, X.; Mei, Y.; Li, A.; Wang, R.; Guo, Z. Research on the Design of an Omnidirectional Leveling System and Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for Tracked Agricultural Chassis in Hilly and Mountainous Terrain. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Cui, M.; Cai, H.; Li, X. Study Status and Developing Trend of Electric Cylinder. J. Mech. Transm. 2015, 39, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, N.A.; Rodriguez, C.F. Real-time dynamic control of a stewart platform. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 390, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhu, X.; Ou, H.; Zhan, C. Dynamic characteristics of electric 6-DOF platform with high speed and heavy load. J. Mach. Des. 2025, 42, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L. Development and prospect of agricultural machinery chassis technology. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 1–15. Available online: https://www.nyjxxb.net/index.php/journal/article/view/1214 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Lei, X.; Zhu, X.; Yang, C.; Bao, C.; Chen, X. Research on the Development Status and Trend of Automobile Suspension. Mech. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025, 54, 1–5+24. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/jxkf202502001 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Hong, L.; Yang, W.; Guo, P.; He, Z. Review of Technique Application and Performance Evaluation for the Vehicle Suspension System. Mach. Des. Res. 2015, 31, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, R.; Jiang, Y. Classification Evolution, Control Strategy Innovation, and Future Challenges of Vehicle Suspension Systems: A Review. Actuators 2025, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Li, Z. Research on Control Strategy of Semi-Active Suspension System Based on Fuzzy Adaptive PID-MPC. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ke, C.; Ke, T.; Li, H.; Wei, W.; Zhao, C. Design and Experiment of Pre-detection Active Leveling Agricultural Chassis for Hilly Area. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Peng, F.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Wei, W.; Zhao, J. Design and Experiment of Adaptive Leveling Chassis for Hilly Area. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 42–47. Available online: https://www.nyjxxb.net/index.php/journal/article/view/465 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Wang, Z. Research on Body Leveling System and Leveling Control of Hily Mountain Tractor. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fialho, I.; Balas, G.J. Road adaptive active suspension design using linear parameter-varying gain-scheduling. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2002, 10, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, P.; Szaszi, I.; Bokor, J. Active suspension design using linear parameter varying control. Int. J. Veh. Auton. Syst. 2003, 1, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Research on Automatic Hydraulic Leveling of Heavy Duty Transporter with Fuzzy PID Control Strategy. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Design of Horizontal Control Svstem of Rotary Tiller Based on Fuzzy PID. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Phu, N.D.; Hung, N.N.; Ahmadian, A.; Senu, N. A new fuzzy PID control system based on fuzzy PID controller and fuzzy control process. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 22, 2163–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Shi, F.; Xie, F.; Zhang, K. A survey of road roughness study. J. Vib. Shock 2009, 28, 95–101+216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Shi, F.; Xie, F.; Zhang, K. Summary of research on road spectrum measurement. J. Electron. Meas. Instrum. 2010, 24, 72–79. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:107964559 (accessed on 3 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Múčka, P. Simulated road profiles according to ISO 8608 in vibration analysis. J. Test. Eval. 2018, 46, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.a.; Tong, J.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yao, M. Modeling method for non-stationary road irregularity based on modulated white noise and lookup table method. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2020, 20, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levelling Method | Levelling Direction | Active/Passive Levelling | Structural Complexity | Terrain Adaptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic differential height type | Lateral only (roll) | Active (hydraulic cylinder driven) | Requires connecting rods, hydraulic pumps, multiple sets of hydraulic cylinders, control valve assemblies, hydraulic piping and reservoirs, occupying substantial space and featuring a complex structure. | Suitable only for single gentle lateral slopes; not applicable to longitudinal slopes or compound slopes (roll + pitch) |

| Parallel four-bar linkage | Lateral only (roll) | Semi-active (hydraulic cylinder driven + passive terrain adaptation) | Requires a parallel four-bar linkage mechanism, multiple sets of hydraulic cylinders, control valve assemblies, hydraulic piping and reservoirs, occupying substantial space and featuring a complex structure. | Suitable only for single gentle horizontal slopes; not applicable to longitudinal slopes or compound slopes |

| Adjustable centre of gravity mechanism | Lateral (roll) + Longitudinal (pitch) | Semi-active (motor-driven centre of gravity shift + passive terrain adaptation) | Requires both horizontal and vertical guide rails, drive motors; simple structure, but occupies considerable space. | Suitable for composite slope (roll + pitch) |

| Bending and twisting the waist | No active levelling direction, only passive adaptation to terrain undulations | Passive (propelled by terrain forces acting upon the articulated shaft/twisting of the waist shaft) | The design of a central waist hinge shaft, a waist-contouring shaft, and their associated structures is required, presenting a complex construction. | Suitable for rough terrain, but unable to handle steep slopes or compound slopes (roll + pitch) |

| Omnidirectional levelling | Lateral (roll) + Longitudinal (pitch) | Semi-active (motor-driven centre-of-gravity shift + passive contouring) | multiple sets of hydraulic cylinders, control valve assemblies, hydraulic piping and reservoirs, occupying substantial space and featuring a complex structure. | Suitable for compound slopes (roll + pitch) and uneven terrain |

| Hydraulic Cylinders | Electric Cylinder | |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission medium | Hydraulic oil | Mechanical structure |

| Transmission efficiency | ≤50% | ≥90% |

| Operating temperature | The operating temperature range for hydraulic cylinders is typically specified as −40 to 120 °C, with performance being susceptible to fluctuations in temperature. | The operating temperature range for electric cylinders is typically specified as −30 to 80 °C, with minimal impact on performance from temperature fluctuations. |

| Structural complexity | Requires hydraulic pumps, hydraulic cylinders, control valve assemblies, hydraulic piping and reservoirs, occupying considerable space and featuring complex structures. | Requires electric motors and mechanical transmission components, occupies minimal space, facilitates convenient layout, and features a simple structure. |

| Position controllability | difficulties | easily |

| Maintenance workload | Large | small |

| Environmental pollution | Hydraulic oil leakage | small |

| Name | Value (m) |

|---|---|

| YA | 0.1 |

| ZA | 0.6 |

| OA | 0.608 |

| OB | 0.18 |

| BC | 0.12 |

| ec | ΔKp/ΔKi/ΔKd | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | NB | NM | NS | ZO | PS | PM | PB | |

| NB | PB/NB/PS | PB/NB/NS | PM/NM/NB | PM/NM/NB | PS/NS/NB | ZO/ZO/NM | ZO/ZO/PS | |

| NM | PB/NB/PS | PB/NB/NS | PM/NM/NB | PS/NS/NM | PS/NS/NM | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/ZO/ZO | |

| NS | PM/NB/ZO | PM/NM/NS | PM/NS/NM | PS/NS/NM | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/PS/NS | NS/PS/ZO | |

| ZO | PM/NM/ZO | PM/NM/NS | PS/NS/NS | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/PS/NS | NM/PM/NS | NM/PM/ZO | |

| PS | PS/NM/ZO | PS/NS/ZO | ZO/ZO/ZO | NS/PS/ZO | NS/PS/ZO | NM/PM/ZO | NB/PB/ZO | |

| PM | PS/ZO/PB | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/PS/PS | NM/PS/PS | NM/PM/PS | NM/PB/PS | NB/PB/PB | |

| PB | ZO/ZO/PB | ZO/ZO/PM | NM/PS/PM | NM/PM/PM | NM/PM/PS | NB/PB/PS | NB/PB/PB | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, P.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Q.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, J. Design and Simulation of Suspension Leveling System for Small Agricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Sensors 2025, 25, 7447. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247447

Huang P, Luo Q, Liu Q, Peng Y, Zheng S, Liu J. Design and Simulation of Suspension Leveling System for Small Agricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7447. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247447

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Peng, Qiang Luo, Quan Liu, Yao Peng, Shijie Zheng, and Jiukun Liu. 2025. "Design and Simulation of Suspension Leveling System for Small Agricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7447. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247447

APA StyleHuang, P., Luo, Q., Liu, Q., Peng, Y., Zheng, S., & Liu, J. (2025). Design and Simulation of Suspension Leveling System for Small Agricultural Machinery in Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Sensors, 25(24), 7447. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247447