AI-Enabled Dynamic Edge-Cloud Resource Allocation for Smart Cities and Smart Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

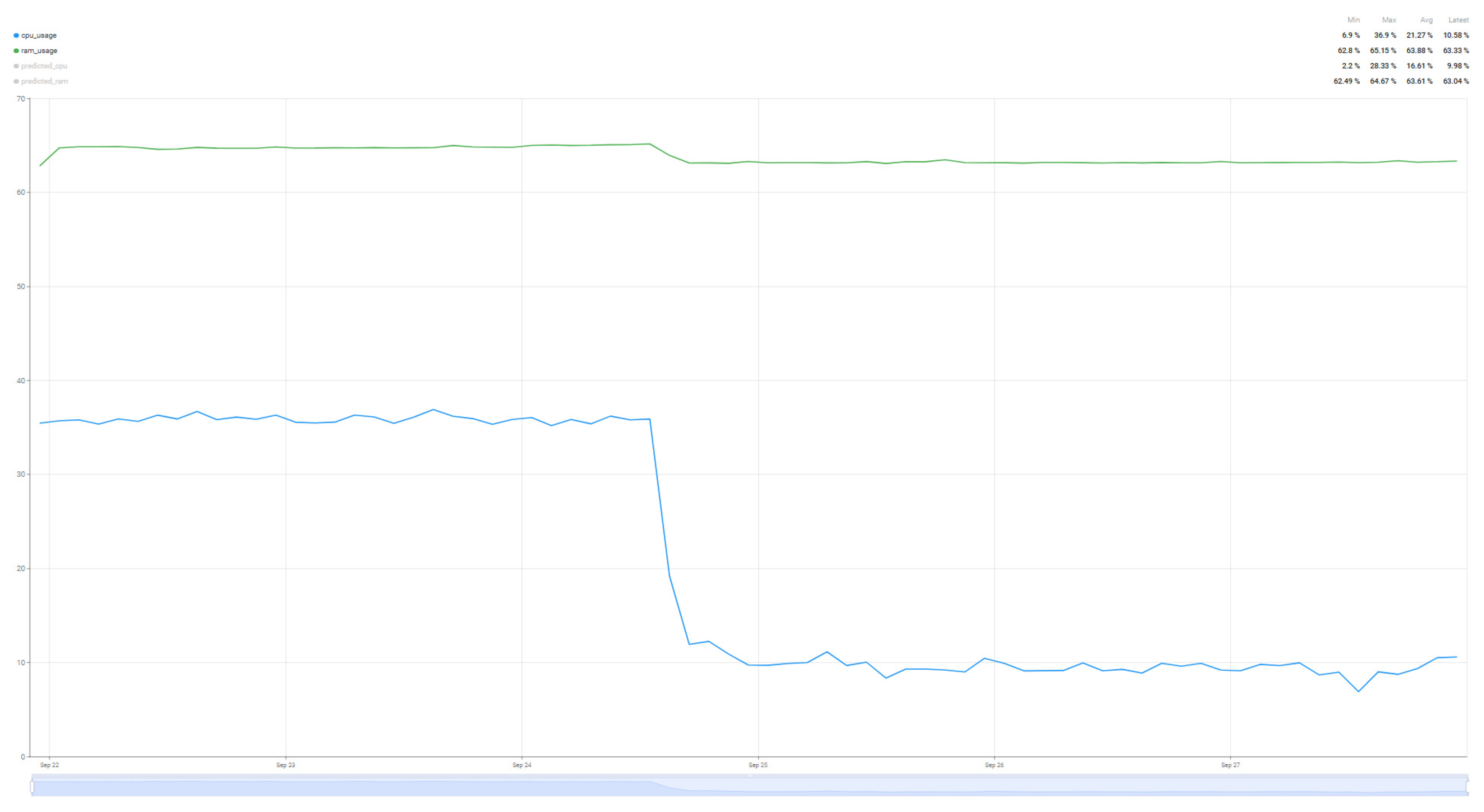

- Continuously trained dynamic resource allocation framework: The proposed technique continuously learns from a 24 h window by analyzing the evolution of CPU and RAM usage. Based on the resource allocation algorithm, the system dynamically switches between cloud and edge nodes at key moments, adapting to changing workloads while maintaining stability.

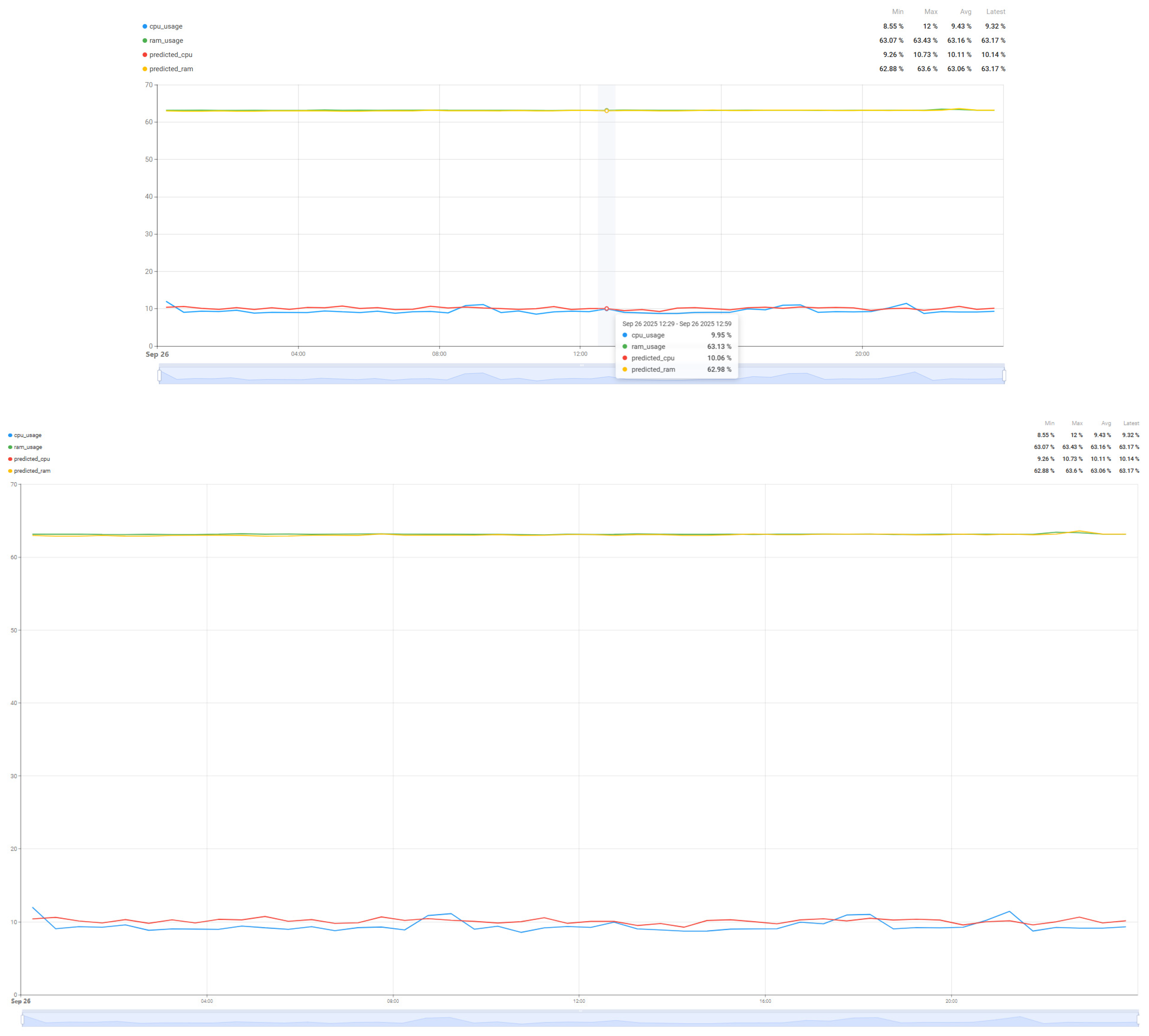

- Predictive modeling and training: The SARIMA algorithm was employed to predict both CPU and RAM usage, and it consistently outperforms the baseline approach across s all four evaluated metrics: RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and MSE. To evaluate its performance under different conditions, testing was conducted in two scenarios: regular instance load and periods when a predictive Random Forest algorithm for air-quality parameters was triggered, introducing additional computational load. These tests demonstrate that the SARIMA model can maintain accurate CPU and RAM forecasts even under increased system demand, with minimal impact on ongoing processes.

- Robustness to critical scenarios: The approach addresses situations where cloud scalability is limited, demand is excessively high, or cloud resources are temporarily unavailable due to network failures. This ensures consistent and dependable operation in dynamic environments characterized by diverse devices and varying workloads.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

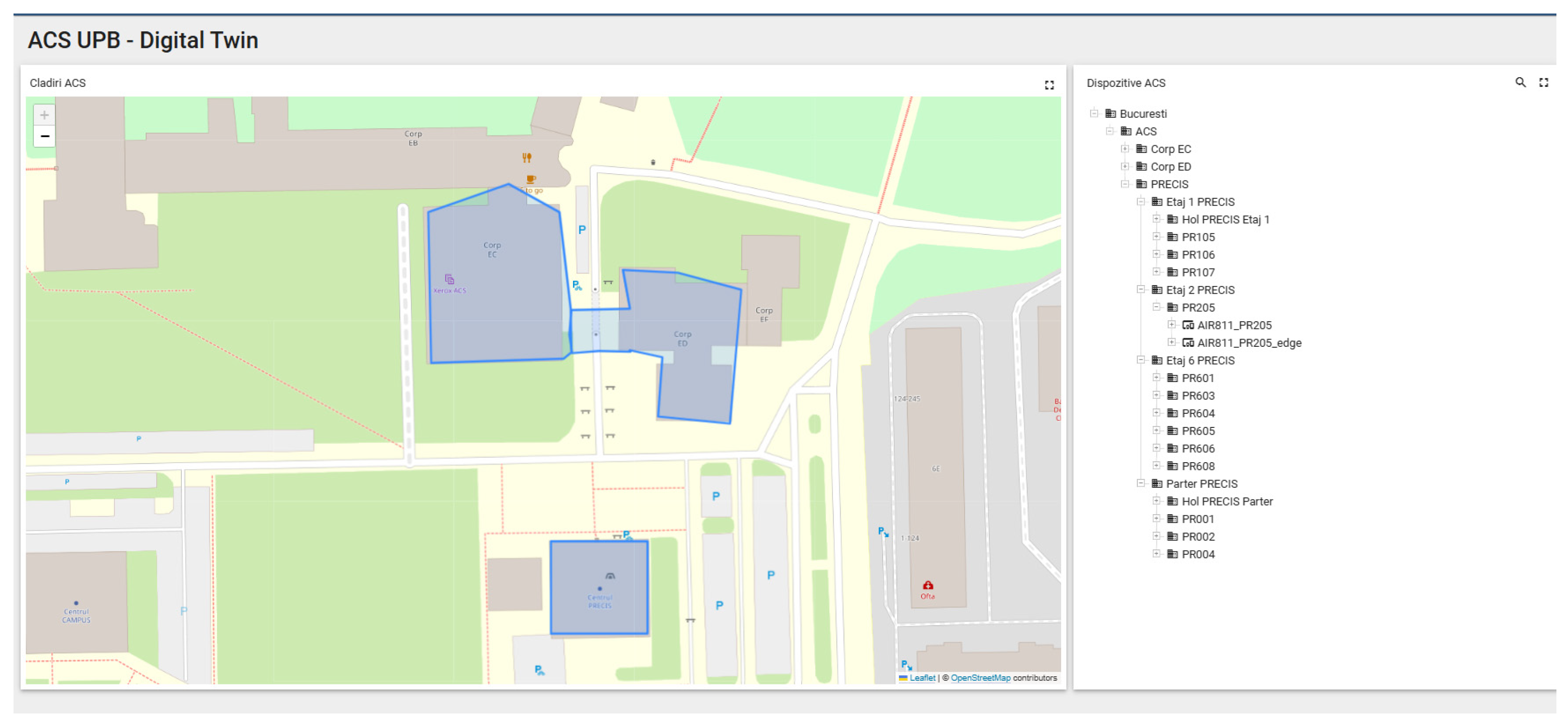

3.1. University Campus Infrastructure

3.2. Quantitative Data Performance Comparison Between Edge and Cloud Nodes

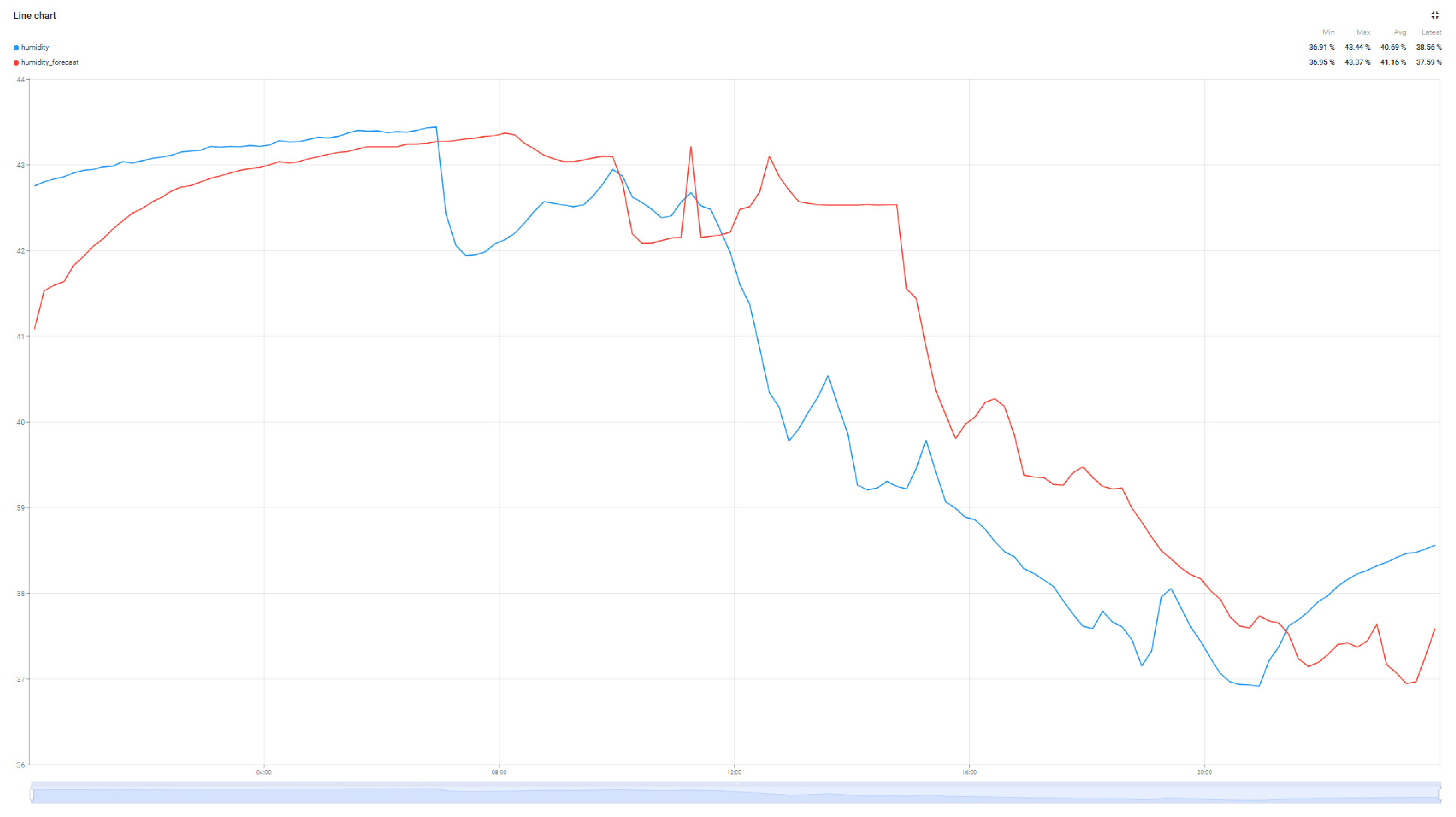

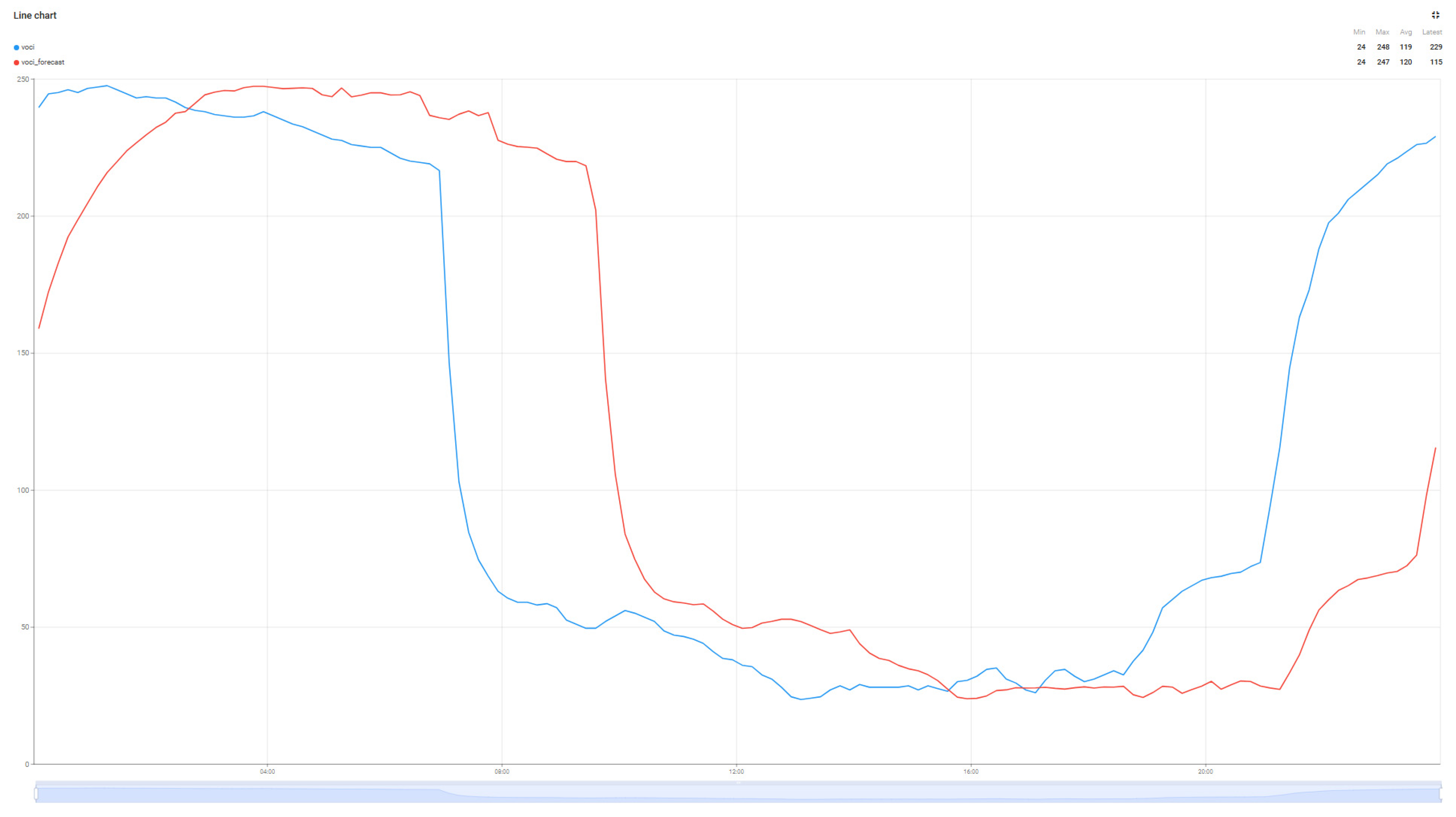

3.3. Air Quality Parameter Prediction Algorithm

- Temperature;

- Humidity;

- VOC Index—Standardized index used to describe the level of volatile organic compounds in the air;

- PM2.5—Particulate Matter 2.5 measures airborne particles with a diameter of up to 2.5 μm;

- DeltaPm10—Variation in PM10 particle concentration between two successive measurements

- DeltaVOCI—Variation in VOC concentration in the reference period

- NOxi—Nitrogen Oxides Index indicates the concentration of Nitrogen Oxides in the air

- Pm1—Particulate Matter 1 measures airborne particles with a diameter of up to 1 μm;

- Pm2—Particulate Matter 2 measures airborne particles with a diameter of up to 2 μm;

- Pm4—Particulate Matter 4 measures airborne particles with a diameter of up to 4 μm;

- Pm10—Particulate Matter 10 measures airborne particles with a diameter of up to 10 μm.

- Data preparation: the values generated by the sensors over a certain time interval are read, and based on them, lagged copies of the time series are built, also called lag features; these are stored in vector form, contain the values for the considered time interval. In other words, lag features are past values of the time series that are used to predict the future state.

- Bootstrap Sampling: The data that can be used for each decision tree is randomly chosen. An important thing to note is that the data can be used by multiple trees.

- Tree construction: Each tree is divided into several branches depending on the configured depth, with the possibility of stopping if it does not have enough data to share, thus reaching a final node, also called a leaf node.

- Aggregation of results. Each tree sends a certain prediction; in this last step, all the predictions generated by the trees are aggregated, thus obtaining a more precise value compared to a single tree that presents a single way of placing the nodes.

3.4. Cloud Edge Switching

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode: Resource switching between Cloud and Edge |

| Input: Status of the Cloud Node and Status of the Edge Node Output: Decision in node selection |

| BEGIN cloud_node_status = GET_STATUS (“Cloud Node status via HTTPS”) edge_node_status = GET_STATUS (“Edge Node status via HTTPS”) IF cloud_node_status == “CONNECTED” THEN use_node(“Cloud Node”) ELSE use_node(“Edge Node”) END IF END |

- α (alpha) represents Service Availability, a binary value {0, 1} determined by a successful TCP handshake on the IoT service port (1883).

- λavg (lambda) is the Average Latency (ms), derived from the Round-Trip Time (RTT) of continuous ICMP packets over a sliding window.

- β (beta) is the Throughput (Mbps), measured via active transmission tests over a fixed duration (using iPerf3).

3.5. Infrastructure and Components Used

3.6. Dynamic Resource Allocation Algorithm

- Data collection and normalization—These are the CPU and RAM load data collected in the Thingsboard platform for the last 24 h, one hour before the current moment. In this step, the quality of the data is checked by checking the number of existing values and validating the 5 min frequency in data collection. The reason for choosing the 5 min interval for reading the data is to correlate with the moment of transmission of information regarding air quality, in order to better see the impact that this process has on resources. In case there are intervals with missing data, these values can be reindexed, or periods with very large gaps are eliminated.

- Transformations—In this step, level variations are checked, and the stationarity of the series is verified.

- Non-sensory and sensory differences—By applying the two components, the aim is to eliminate linear trends and the repetitive component.

- Defining the model underlying the algorithm:

- 5.

- Parameter estimation—Using numerical optimization to achieve the most stable fit.

- 6.

- Residuals—Checking the autocorrelation between the residuals, if it exists, the parameters must be adjusted.

- 7.

- Multi-step forecast—Using previous predictions to obtain more accurate values.

- 8.

- Post-processing—Additional steps may be applied for calibration or setting an offset.

- SARIMA (1, 1, 1) (1, 1, 1)

- SARIMA (0, 1, 1) (2, 1, 1)

- SARIMA (0, 1, 1) (1, 1, 0)

- SARIMA (0, 1, 2) (1, 1, 1)

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode: Resource switching between Cloud and Edge based on Resource Utilization |

| Input: Status of the Cloud Node and Status of the Edge Node Resource Allocation Algorithm Decision Output: Decision in node selection |

| BEGIN cloud_node_status = GET_STATUS (“Cloud Node status via HTTPS”) edge_node_status = GET_STATUS (“Edge Node status via HTTPS”) IF cloud_node_status == “CONNECTED” decision = ResourceAllocationAlgorithm (CPU, RAM) IF decision == “USE_CLOUD” THEN use_node (“Cloud Node”) ELSE IF decision == “USE_EDGE” THEN use_node (“Edge Node”) ELSE use_node (“Current Node”) ENDIF ELSE use_node (“Edge Node”) ENDIF END |

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Quantitative Data Performance Comparison Between Edge and Cloud Nodes

4.2. Random Prediction Performance

4.3. Random Forest CPU and RAM Impact

4.4. SARIMA CPU and RAM Prediction

- is the term to be predicted.

- is the observed value at lag k.

- is the number of observations in the chosen time window.

4.5. Dynamic Resource Allocation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Average Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| VOC Index | Volatile Organic Compounds Index |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SMA | Simple Moving Average |

References

- Attaran, H.; Kheibari, N.; Bahrepour, D. Toward integrated smart city: A new model for implementation and design challenges. GeoJournal 2022, 87 (Suppl. S4), 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckman, A.H.; Mayfield, M.; BM Beck, S. What is a smart building? Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2014, 3, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Yaqoob, I.; Adnane, A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, S. Internet-of-things-based smart cities: Recent advances and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vailshery, L.S. Number of IoT Connections Worldwide 2022–2034. Statista. 26 June 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Singhvi, H. The Internet of Things in 2025: Trends, Business Models, and Future Directions for A Connected World. Int. J. Internet Things (IJIT) 2025, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Puryear, N.; Abdelwahed, S.; Zohrabi, N. A review of IoT-based smart city development and management. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1462–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xia, F. Edge computing for internet of everything: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 23472–23485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J.; Karthikeyan, B. Dynamic priority-based task scheduling and adaptive resource allocation algorithms for efficient edge computing in healthcare systems. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Artificial intelligence-based public safety data resource management in smart cities. Open Comput. Sci. 2023, 13, 20220271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, K.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Ahmed, I.; Guizani, M. Intelligent and secure edge-enabled computing model for sustainable cities using green internet of things. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothamali, P.R.; Mandaloju, N.; Dandyala, S.S.M. Optimizing Resource Management in Smart Cities with AI. Unique Endeavor Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 174–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Ullah, I.; Singh, S.K.; Sharafian, A.; Jiang, W.; Sherazi, H.I.; Bai, X. Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation for Urban Traffic Flow Prediction in Edge-Cloud Computing. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2025, 1863025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambala, G. Edge Computing for IoT-Driven Smart Cities: Challenges and Opportunities in Real-time Data Processing. IRE J. 2024, 8, 744–760. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E.; Ahmed, A.; Yaqoob, I.; Shuja, J.; Gani, A.; Imran, M.; Shoaib, M. Bringing computation closer toward the user network: Is edge computing the solution? IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narne, H. The role of edge computing in enhancing data processing efficiency. Int. J. EDGE Comput. (IJEC) 2022, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Leung, V.; Niyato, D.; Yan, X.; Chen, X. Convergence of edge computing and deep learning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.08349. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.H.; Seo, Y.S. Understanding edge computing: Engineering evolution with artificial intelligence. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164229–164245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Dong, N.; Li, W.; Cao, J. Edge computing with artificial intelligence: A machine learning perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Liu, S.; Xiong, X.; Cai, Z.; Tu, G. A survey of recent advances in edge-computing-powered artificial intelligence of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 13849–13875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amangeldy, B.; Imankulov, T.; Tasmurzayev, N.; Dikhanbayeva, G.; Nurakhov, Y. A Review of Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning Approaches for Resource Management in Smart Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, H.; Malehmirchegini, L.; Bejan, A.; Afolabi, T.; Mulumba, A.; Daka, P.P. Artificial intelligence evolution in smart buildings for energy efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, M.; Jain, S.C. A predictive priority-based dynamic resource provisioning scheme with load balancing in heterogeneous cloud computing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 62653–62664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Hu, Z.Z.; Ren, Z. Geometrized task scheduling and adaptive resource allocation for large-scale edge computing in smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 14398–14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, K.C.; Shivakumar, B.R.; Nagaraja, R. Resource utilization prediction in cloud computing using hybrid model. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Ma, L.; Ji, Y.; Cong, J.; Xu, M.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y. Multi-layer guided reinforcement learning task offloading based on Softmax policy in smart cities. Comput. Commun. 2025, 235, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.A.V.; Laureano, E.V.; Betancourt, R.O.J.; Alvarez, E.N. An open source IoT edge-computing system for monitoring energy consumption in buildings. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, Q.V.; Nguyen, V.H.; Minh, Q.N.; Van, A.D.; Le Anh, N.; Chehri, A. An efficient edge computing management mechanism for sustainable smart cities. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2023, 38, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigka, M.; Dritsas, E. Edge and cloud computing in smart cities. Future Internet 2025, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; Yaqoob, I.; Tran, N.H.; Kazmi, S.A.; Dang, T.N.; Hong, C.S. Edge-computing-enabled smart cities: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 10200–10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walani, C.C.; Doorsamy, W. Edge vs. Cloud: Empirical Insights into Data-Driven Condition Monitoring. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bai, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y. Resource and replica management strategy for optimizing financial cost and user experience in edge cloud computing system. Inf. Sci. 2020, 516, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, B.; Luo, J.; Zhang, J. Deadline-aware dynamic task scheduling in edge–cloud collaborative computing. Electronics 2022, 11, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lin, D. Dynamic task allocation for cost-efficient edge cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC), Beijing, China, 7–11 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Pang, S.; Qiao, S.; Gui, H.; Yu, S.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Mumtaz, S.; Lyu, Z. Real-Time Scheduling of CPU/GPU Heterogeneous Tasks in Dynamic IoT Systems: Enhancing GPU and Memory Efficiency. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 25, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, W.; Lu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Fu, X. Efficient resource allocation for on-demand mobile-edge cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 8769–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.; He, Q.; Cui, G.; Xia, X.; Abdelrazek, M.; Chen, F.; Hosking, J.; Grundy, J.; Yang, Y. QoE-aware user allocation in edge computing systems with dynamic QoS. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 112, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Sahoo, K.S.; Sahoo, B.; Gandomi, A.H. An auction based edge resource allocation mechanism for IoT-enabled smart cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Canberra, ACT, Australia, 1–4 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1280–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, O.A.; Abdellah, A.R.; Muthanna, A.; Koucheryavy, A. Distributed edge computing for resource allocation in smart cities based on the IoT. Information 2022, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficili, I.; Giacobbe, M.; Tricomi, G.; Puliafito, A. From sensors to data intelligence: Leveraging IoT, cloud, and edge computing with AI. Sensors 2025, 25, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P. IoT-Based Smart City Grid Optimization Using AI and Edge Computing. Soft Comput. Fusion Appl. 2024, 1, 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Z.; Xiao, M.; Xu, J.; Skoglund, M.; Di Renzo, M. The larger the merrier? Efficient large AI model inference in wireless edge networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrabani, M.M.N.; Apanaviciene, R. An AI-based evaluation framework for smart building integration into smart city. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Islam, M.; Hossain, I.; Ahmed, A. Utilizing AI and data analytics for optimizing resource allocation in smart cities: A US based study. Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Li, J.; Sulaiman, R.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Elattar, S.; Abuhussain, M. Air Quality Prediction and Multi-Task Offloading based on Deep Learning Methods in Edge Computing. J. Grid Comput. 2023, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Quang, T.; Doan, D.T.; Ngarambe, J.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Zhang, T. AI management platform for privacy-preserving indoor air quality control: Review and future directions. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagan, C.A.; Joe, S.S.A.; Mary, S.J.; Jijo, E.E. Predictive analysis-based sustainable waste management in smart cities using IoT edge computing and blockchain technology. Comput. Ind. 2025, 166, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cai, H.; Yu, H.; Sun, Y.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, L. A short-term energy prediction system based on edge computing for smart city. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Kuthadi, V.M.; Baskar, S. Smart building energy management and monitoring system based on artificial intelligence in smart city. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X. Dynamic resource management in MEC powered by edge intelligence for smart city internet of things. J. Grid Comput. 2024, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Lin, W.; Shi, F.; Li, J.; Qi, D.; Fong, S. A novel approach for CPU load prediction of cloud server combining denoising and error correction. Computing 2023, 105, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Lu, S. Computing resource allocation strategy based on cloud-edge cluster collaboration in internet of vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10790–10803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.; Bartz, R.; Durairajan, R.; Kremer, U.; Kannan, S. Are Edge MicroDCs Equipped to Tackle Memory Contention? In HotStorage ′25, Proceedings of the 17th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 10–11 July 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tuli, S.; Ilager, S.; Ramamohanarao, K.; Buyya, R. Dynamic scheduling for stochastic edge-cloud computing environments using a3c learning and residual recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2020, 21, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorali, M.; Righetti, F.; Vallati, C.; Das, S.K.; Anastasi, G. Dynamic Resource Allocation in Cloud-to-Things Continuum for Real-Time IoT Applications. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), Cork, Ireland, 16–19 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 432–437. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, P. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based resource allocation for cloud gaming via edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 5364–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Yang, H. Cloud computing load prediction method based on CNN-BiLSTM model under low-carbon background. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, C.; Wolter, K.; Xu, M. Collaborate edge and cloud computing with distributed deep learning for smart city internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8099–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingsboard. ThingsBoard Community Edition. Available online: https://thingsboard.io/docs/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Halabaku, E.; Bytyçi, E. Overfitting in Machine Learning: A Comparative Analysis of Decision Trees and Random Forests. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2024, 39, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Yang, H.S. Comparative Study of Time Series Analysis Algorithms Suitable for Short-Term Forecasting in Implementing Demand Response Based on AMI. Sensors 2024, 24, 7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.L.; Shams, S.M.; Ullah, S.M. Time-series and deep learning approaches for renewable energy forecasting in Dhaka: A comparative study of ARIMA, SARIMA, and LSTM models. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisetti, M.; Ardagna, C.A.; Balestrucci, A.; Bena, N.; Damiani, E.; Yeun, C.Y. On the robustness of random forest against untargeted data poisoning: An ensemble-based approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2023, 8, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swari, M.H.P.; Handika, I.P.S.; Satwika, I.K.S. Comparison of simple moving average, single and modified single exponential smoothing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 7th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 6–8 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Author (s) | Algorithm | Scope | Smart Building | Smart City | Using Edge/Cloud | Using Dynamic Allocation of Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo, H. et al. [47] | Online Neural Network | Energy consumption prediction | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Palagan, C.A. et al. [46] | RF algorithm and blockchain | Waste management | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ real-time data from IoT devices |

| Selvaraj, R. et al. [48] | AIMS-SB | Energy management | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Wan, X. [49] | Federated Learning LO-DDPG algorithm | Cost reduction | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ optimization issues for the CPU frequencies, transmit power, IoT device offloading decisions |

| Zhao, H. et al. [9] | Back-propagation Neural Network (BPNN) | Public safety | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Sun, C. et al. [44] | Deep-Learning | Air quality | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Van Quang, T. et al. [45] | Artificial Neural Networks | Indoor air quality | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Author (s) | Interest Parameters | Prediction | CPU | Mono-Processor Multi-Processor | RAM Memory | Virtual/Physical | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| You, D. et al. [50] | Only CPU utilization | ✓ | ✓ | Not specified | ✗ | Not specified | Noise filtering |

| Anupama, K.C. et al. [24] | CPU and Memory utilization | ✓ | ✓ | Not specified | ✓ | Not specified | information of 1250 VMs- 30-day duration with the sample rate of 5 min |

| Tran, L. et al. [52] | CPU and Ram | ✗ | ✓ | 16-core 2.1 GHz Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4110 | ✓ | 48 GB DRAM | OS and applications coordinate to manage memory dynamically manages large volumes of sensor data |

| Shen, X. et al. [51] | CPU | ✗ | ✓ | 2.4 GHz CPU | ✗ | 16 GB | Analyzing the performance with different numbers of task between 10 and 150 |

| Tuli, S. et al. [53] | CPU, RAM and disk, and network bandwidth | ✓ | ✓ | Intel i7-7700K | ✓ | 8 GB graphics RAM | Looking at the number of tasks completed and the avg response time |

| Deng, X. et al. [55] | CPU Latency fairness, and load balance | ✓ | ✓ | Not specified | ✗ | Not specified | The number of tasks per server varies |

| Pettorali, M. et al. [54] | CPU Memory, number of mobile nodes | ✓ | ✓ | Different scenarios, 1 to 5 GHz | ✓ | 8 GB | Considers the number of mobile nodes in the system |

| Lai, P. et al. [36] | CPU, RAM, storage, bandwidth | ✗ | ✓ | i5-7400T processor (4 CPUs, 2.4 GHz) | ✓ | 8 GB RAM | quality of service and quality of experience |

| Anand, J. et al. [8] | CPU RAM Local and Cloud Latency | ✓ | ✓ | [500, 3000] Edge MIPS [2000, 10,000] Cloud MIPS | ✓ | Edge Node 32 Gb Cloud Node 64 GB | Time, execution time, and energy consumption |

| Li, C. et al. [31] | CPU, number of rented nodes, SLA default rate, and cost | ✓ | ✓ | Single Multi-Core comparison | ✗ | Up to 32, depending on the configuration | Comparing the performance/costs of 12 different configurations |

| Author (s) | Prediction Algorithm | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| You, D. et al. [50] | CEEMDAN-LSTM-RIDGE | ✓ 1.3141 | 0.8966 ✓ | 3.2030 ✓ | ✗ |

| Palagan, C.A. et al. [46] | Random Forest | ✗ | 0.08 ✓ | ✗ | 0.12 ✓ |

| Kothamali, P.R. et al. [12] | Adaptive Resilient Node (ARN) Coordination Algorithm | Different values depending on the scenario ✓ | Different values depending on the scenario ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Anupama, K.C. et al. [24] | SARIMA | ✗ | 5.83 for CPU, higher values for memory prediction ✓ | 0.49 for CPU, higher values for memory prediction ✓ | ✗ |

| Zhang, H. et al. [56] | Neural Network (CNN-BiLSTM) | ✗ | 0.2387 ✓ | ✗ | 0.2222 ✓ |

| Luo, H. et al. [47] | Online Neural Network | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Only graphical interpretation, no exact values ✓ |

| Wu, H. et al. [57] | Distributed Deep Learning-Driven Task Offloading (DDTO) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Not specified ✓ |

| Author (s) | Parameter Prediction for Smart City/Smart Building | Edge Computing with Dynamic Allocation | Prediction on the Evolution of the Computer Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luo, H. et al. [47] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Palagan, C.A. et al. [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| You, D. et al. [50] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ error correction and data denoising |

| Zhang, H. et al. [56] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ real-time power prediction based on resource utilization |

| Anupama, K.C. et al. [24] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ Hibrid prediction, statistical + machine learning |

| Anand, J. et al. [8] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ali, A. et al. [12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Selvaraj, R. et al. [48] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Zhang, Y. et al. [32] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ time-sensitive scheduling and priority algorithms |

| Ding, S. et al. [33] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Pettorali, M. et al. [54] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ for real-time application |

| Romero, D.A. et al. [26] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Our Solution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| N_estimators | Number of trees used | 300 |

| max_depth | Maximum depth of trees | 8 |

| min_samples_split | Minimum number of samples in node for division | 3 |

| min_samples_leaf | Minimum number of samples from an end node/leaf node | 2 |

| max_features | Maximum number of features considered for each split | sqrt |

| n_lags | Lag copies of a time series | 288 |

| historic_days | Number of days used for prediction | 1 |

| prediction_hours | The number of hours for which the prediction is made | 1 |

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Processor | Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2660 v2 @ 2.20 GHz, 4 cores |

| Memory | 4 GB RAM |

| Operating System | CentOS Stream Linux 8 |

| Kernel | kernel-4.18.0-553.6.1.el8.x86_64 |

| ThingsBoard | 3.8.1 |

| Database | PostgreSQL version 12.22 |

| Java OpenJDK | 17.0.12 |

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Development Board | Raspberry Pi 2B |

| Processor | ARM Cortex-A7 @ 900 MHz |

| Memory | 1 GB RAM |

| Operating System | Raspbian Linux 12 |

| Kernel | 6.6.62 + rpt-rpi-v7 |

| ThingsBoard Edge | 3.8.0 |

| Database | PostgreSQL 15.9 |

| Java OpenJDK | 17.0.13 |

| Connection Between | Protocol | Port |

|---|---|---|

| Users and Platform | HTTPS | 8080 |

| Sensors and Edge | MQTT | 1833 |

| Edge node and Cloud | RPC | 7070 |

| Sensors and Cloud | MQTT | 1833 |

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| p | Non-seasonal autoregression | 0 |

| d | Non-seasonal differentiation | 1 |

| q | Non-seasonal Moving Average | 1 |

| P | Seasonal autoregression | 1 |

| D | Seasonal differentiation | 1 |

| Q | Seasonal Moving Average | 1 |

| s | Length of the seasonal cycle | 12 |

| historic_days | Number of days used for training | 1 |

| prediction_hours | The number of hours for which the prediction is made | 1 |

| Metric | Cloud Node | Edge Node | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 241 | 285 | 288 |

| Max | 287 | 288 | 288 |

| AVG | 282 | 287 | 288 |

| Total | 2820 | 2867 | 2880 |

| Metric | CPU | CPU (Baseline) | RAM | RAM (Baseline) | CPU Improvement (%) | RAM Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 2.135454977 | 2.896112677 | 0.45163613 | 0.562766783 | 26.264 | 19.747 |

| MAE | 1.331007752 | 1.775537634 | 0.262015504 | 0.363548387 | 25.036 | 27.928 |

| MAPE | 4.285011928 | 5.546733386 | 0.409304104 | 0.565485126 | 22.747 | 27.618 |

| MSE | 4.560167959 | 8.387468638 | 0.203975194 | 0.316706452 | 45.631 | 35.594 |

| Metric | CPU | CPU (Baseline) | RAM | RAM (Baseline) | CPU Improvement (%) | RAM Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 1.025028997 | 1.718717676 | 0.149816348 | 0.185563462 | 40.360 | 19.264 |

| MAE | 0.945694444 | 1.493454936 | 0.122361111 | 0.164141631 | 36.677 | 25.453 |

| MAPE | 10.23814828 | 12.79209577 | 0.19367763 | 0.259492897 | 19.965 | 25.363 |

| MSE | 1.054600463 | 2.953990451 | 0.023613889 | 0.034433798 | 64.299 | 31.422 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dumitru, M.-C.; Caramihai, S.-I.; Dumitrascu, A.; Pietraru, R.-N.; Moisescu, M.-A. AI-Enabled Dynamic Edge-Cloud Resource Allocation for Smart Cities and Smart Buildings. Sensors 2025, 25, 7438. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247438

Dumitru M-C, Caramihai S-I, Dumitrascu A, Pietraru R-N, Moisescu M-A. AI-Enabled Dynamic Edge-Cloud Resource Allocation for Smart Cities and Smart Buildings. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7438. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247438

Chicago/Turabian StyleDumitru, Marian-Cosmin, Simona-Iuliana Caramihai, Alexandru Dumitrascu, Radu-Nicolae Pietraru, and Mihnea-Alexandru Moisescu. 2025. "AI-Enabled Dynamic Edge-Cloud Resource Allocation for Smart Cities and Smart Buildings" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7438. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247438

APA StyleDumitru, M.-C., Caramihai, S.-I., Dumitrascu, A., Pietraru, R.-N., & Moisescu, M.-A. (2025). AI-Enabled Dynamic Edge-Cloud Resource Allocation for Smart Cities and Smart Buildings. Sensors, 25(24), 7438. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247438