Immunofluorescence Rapid Analysis of Bisphenol A in Water Based on Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots

Highlights

- Magnetic particles and quantum dots are used as an enhancing component, which were able to reduce the detection limit by 20 times compared to the use of magnetic particles alone.

- The use of magnetic preconcentration made it possible to further reduce the detection limit by 100 times.

- The article is devoted to the development of a highly sensitive immunochromatographic assay for the determination of bisphenol A in natural water.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials; Enzymes and Processing Aids; Lambré, C.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; et al. Re-evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e06857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamphaya, T.; Pouyfung, P.; Kuraeiad, S.; Vattanasit, U.; Yimthiang, S. Current aspect of bisphenol A toxicology and its health effects. Trends Sci. 2021, 18, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaton, N.J.; Wadia, P.R.; Rubin, B.S.; Zalko, D.; Schaeberle, C.M.; Askenase, M.H.; Gadbois, J.L.; Tharp, A.P.; Whitt, G.S.; Sonnenschein, C. Perinatal exposure to environmentally relevant levels of bisphenol A decreases fertility and fecundity in CD-1 mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michenzi, C.; Myers, S.H.; Chiarotto, I. Bisphenol A in water systems: Risks to polycystic ovary syndrome and biochar-based adsorption remediation: A review. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202401037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, M.; Sollner Dolenc, M. Mechanisms of bisphenol A and its analogs as endocrine disruptors via nuclear receptors and related signaling pathways. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2397–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, A.; Sirohi, R.; Balakumaran, P.A.; Reshmy, R.; Madhavan, A.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Kumar, Y.; Kumar, D.; Sim, S.J. The hazardous threat of Bisphenol A: Toxicity, detection and remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsauliya, K.; Bhateria, M.; Sonker, A.; Singh, S.P. Determination of bisphenol analogues in infant formula products from India and evaluating the health risk in infants asssociated with their exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3932–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousoumah, R.; Leso, V.; Iavicoli, I.; Huuskonen, P.; Viegas, S.; Porras, S.P.; Santonen, T.; Frery, N.; Robert, A.; Ndaw, S. Biomonitoring of occupational exposure to bisphenol A, bisphenol S and bisphenol F: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsmann, R.D.; Will, C.; Carasek, E. Determination of bisphenol A: Old problem, recent creative solutions based on novel materials. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 1148–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrarca, M.H.; Perez, M.A.F.; Tfouni, S.A.V. Bisphenol A and its structural analogues in infant formulas available in the Brazilian market: Optimisation of a UPLC-MS/MS method, occurrence, and dietary exposure assessment. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vom Saal, F.S.; Hughes, C. An extensive new literature concerning low-dose effects of bisphenol A shows the need for a new risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Chen, S.; Zeng, C.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Chen, W. Estrogenic and non-estrogenic effects of bisphenol A and its action mechanism in the zebrafish model: An overview of the past two decades of work. Environ. Int. 2023, 176, 107976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Yadav, A.K.; Rathee, G.; Dhingra, K.; Mukherjee, M.D.; Solanki, P.R. Prospects of nanomaterial-based biosensors: A smart approach for bisphenol-A detection in dental sealants. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 027516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudakov, Y.O.; Selemenev, V.; Khorokhordin, A.; Volkov, A. chromatographic methods for determining free bisphenol A in technical and food products. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 79, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wei, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Sample preparation and analytical methods for bisphenol endocrine disruptors from foods: State of the art and future perspectives. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpourmir, H.; Moradzehi, M.; Velayati, M.; Taghizadeh, S.F.; Hashemzaei, M.; Rezaee, R. Global occurrence of bisphenol compounds in breast milk and infant formula: A systematic review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 211, 116389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S.; Cunha, C.; Ferreira, A.; Fernandes, J. Determination of bisphenol A and bisphenol B in canned seafood combining QuEChERS extraction with dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 404, 2453–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Lu, H.; Shi, L.; Wang, P.; Ali, Z.; Li, J. Electrochemical detection of bisphenols in food: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, A.; Hamed, M.; Mansour, F.R. Reshaping capillary electrophoresis with state-of-the-art sample preparation materials: Exploring new horizons. Electrophoresis 2024, 46, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, K.; Rastogi, N.K.; Thakur, M. Sensors and biosensors for analysis of bisphenol-A. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 52, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Andou, Y. Detection and remediation of bisphenol A (BPA) using graphene-based materials: Mini-review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 6869–6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Wang, L.; Lei, H.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, Z. Antibody production and application for immunoassay development of environmental hormones: A review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yixian, W. Recent advances in metal–organic frameworks as emerging platforms for immunoassays. TrAC Trends Anal. Chemistry. 2024, 171, 117520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, J.; Li, C.; Ma, M.; Yu, W.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z. Molecularly imprinted polymer as an antibody substitution in pseudo-immunoassays for chemical contaminants in food and environmental samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2561–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Qiu, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L. Microfluidic biochips for single-cell isolation and single-cell analysis of multiomics and exosomes. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandenius, C.F. Realization of user-friendly bioanalytical tools to quantify and monitor critical components in bio-industrial processes through conceptual design. Engin. Life Sci. 2022, 22, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahirwar, R.; Bhattacharya, A.; Kumar, S. Unveiling the underpinnings of various non-conventional ELISA variants: A review article. Exp. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cezaro, A.M.; Ballen, S.C.; Hoehne, L.; Steffens, J.; Steffens, C. Cantilever nanobiosensors applied for endocrine disruptor detection in water: A review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.L.; Rani, V. Biosensors for toxic metals, polychlorinated biphenyls, biological oxygen demand, endocrine disruptors, hormones, dioxin, phenolic and organophosphorus compounds: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Bu, T.; Wang, Z.; Shao, B. Integration of a new generation of immunochromatographic assays: Recent advances and future trends. Nano Today 2024, 57, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Shu, R.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Evaluation of the multidimensional enhanced lateral flow immunoassay in point-of-care nanosensors. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 27167–27205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysyan, A. Development of Immunoassays for the Rapid Determination of the Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A Released from Polymer Materials and Products. Ph.D. Thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.K.; Huang, P.Y.; Dutta, S.; Rochet, J.C.; Stanciu, L.A. Tuning a bisphenol A lateral flow assay using multiple gold nanosystems. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2019, 36, 1900133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysyan, A.; Schneider, R.J. Development of a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) to screen for the release of the endocrine disruptor bisphenol A from polymer materials and products. Biosensors 2021, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Kang, L.; Pang, F.; Li, H.; Luo, R.; Luo, X.; Sun, F. A signal-enhanced lateral flow strip biosensor for ultrasensitive and on-site detection of bisphenol A. Food Agric. Immunol. 2018, 29, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlina, A.N.; Komova, N.S.; Serebrennikova, K.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Comparison of conjugates obtained using DMSO and DMF as solvents in the production of polyclonal antibodies and ELISA development: A case study on bisphenol A. Antibodies 2024, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien Pham, T.T.; Cao, C.; Sim, S.J. Application of citrate-stabilized gold-coated ferric oxide composite nanoparticles for biological separations. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.-Y.; Xie, H.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Wu, L.-L.; Hu, J.; Tang, M.; Wu, M.; Pang, D.-W. Fluorescent/magnetic micro/nano-spheres based on quantum dots and/or magnetic nanoparticles: Preparation, properties, and their applications in cancer studies. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12406–12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, U.M. Purification of Antibodies Using Ammonium Sulfate Fractionation or Gel Filtration. In Immunocytochemical Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology™; Javois, L.C., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1999; Volume 115, pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlina, A.N.; Taranova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Vengerov, Y.Y.; Dzantiev, B.B. Quantum dot-based lateral flow immunoassay for detection of chloramphenicol in milk. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 4997–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Santos, T.A. Sensors and biosensors based on magnetic nanoparticles. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 62, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urusov, A.; Petrakova, A.; Zherdev, A.; Dzantiev, B. Application of magnetic nanoparticles in immunoassay. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2017, 12, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Arquer, F.P.; Talapin, D.V.; Klimov, V.I.; Arakawa, Y.; Bayer, M.; Sargent, E.H. Semiconductor quantum dots: Technological progress and future challenges. Science 2021, 373, eaaz8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, K.; Rai, H.; Mondal, S. Quantum dots: An overview of synthesis, properties, and applications. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, A.A.; Ovchinnikov, O.V.; Weinstein, I.A.; Rempel’, S.V.; Kuznetsova, Y.V.; Naumov, A.V.; Smirnov, M.S.; Eremchev, I.Y.; Vokhmintsev, A.S.; Savchenko, S.S. Quantum dots: Modern methods of synthesis and optical properties. Uspekhi Khimii 2024, 93, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Kalashgrani, M.Y.; Gholami, A.; Omidifar, N.; Binazadeh, M.; Chiang, W.-H. Recent advances in quantum dot-based lateral flow immunoassays for the rapid, point-of-care diagnosis of COVID-19. Biosensors 2023, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Wu, T.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.-F.; Wang, J.-H.; Hao, J.-X.; Gao, S.; Hu, G.-S. Application of quantum dots-based immunoassay in food safety detection. Food Res. Dev. 2022, 43, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.K.; Selvan, S.T.; Lee, S.S.; Papaefthymiou, G.C.; Kundaliya, D.; Ying, J.Y. Silica-coated nanocomposites of magnetic nanoparticles and quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4990–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, R.; Mulder, W.J.; Van Schooneveld, M.M.; Strijkers, G.J.; Meijerink, A.; Nicolay, K. Magnetic quantum dots for multimodal imaging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 1, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, L.; Turemis, M.; Marini, B.; Ippodrino, R.; Giardi, M.T. Better together: Strategies based on magnetic particles and quantum dots for improved biosensing. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yin, R.; Guan, G.; Liu, H.; Song, G. Renal clearable magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging and guided therapy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 16, e1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stueber, D.D.; Villanova, J.; Aponte, I.; Xiao, Z.; Colvin, V.L. Magnetic nanoparticles in biology and medicine: Past, present, and future trends. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komova, N.S.; Serebrennikova, K.V.; Berlina, A.N.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Dual lateral flow test for simple and rapid simultaneous immunodetection of bisphenol A and dimethyl phthalate, two priority plastic related environmental contaminants. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Lin, Q.; He, X.; Xing, X.; Lian, W. Electrochemical sensor for bisphenol A detection based on molecularly imprinted polymers and gold nanoparticles. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2011, 41, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.W.; Yoo, J.-W.; Kang, J.; Dua, P.; Lee, D.-K.; Hong, S. Development of single-stranded DNA aptamers for specific bisphenol A detection. Oligonucleotides 2011, 21, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, R.; Amjadi, M.; Hallaj, T.; Narimani, S. A dual chemiluminescence and ratiometric fluorescence sensor based on WS2 QDs-Fe (II)-S2O82—System for bisphenol A detection. Opt. Mater. 2023, 144, 114320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, K.M.; Espino, M.P. Occurrence and distribution of hormones and bisphenol A in Laguna Lake, Philippines. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñalver, R.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Campillo, N.; Viñas, P. Targeted and untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of honey samples for determination of migrants from plastic packages. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lu, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction for four phenolic environmental estrogens in water samples followed by determination using capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 2502–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Duan, W.; Shi, Y.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S. Sensitive detection of bisphenol A in drinking water and river water using an upconversion nanoparticles-based fluorescence immunoassay in combination with magnetic separation. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 5313–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Color Intensity of Analytical Zones, Relative Units * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Concentration of BPA, μg/mL | Without Concentration | Concentration from 1 mL | Concentration from 5 mL | Concentration from 10 mL |

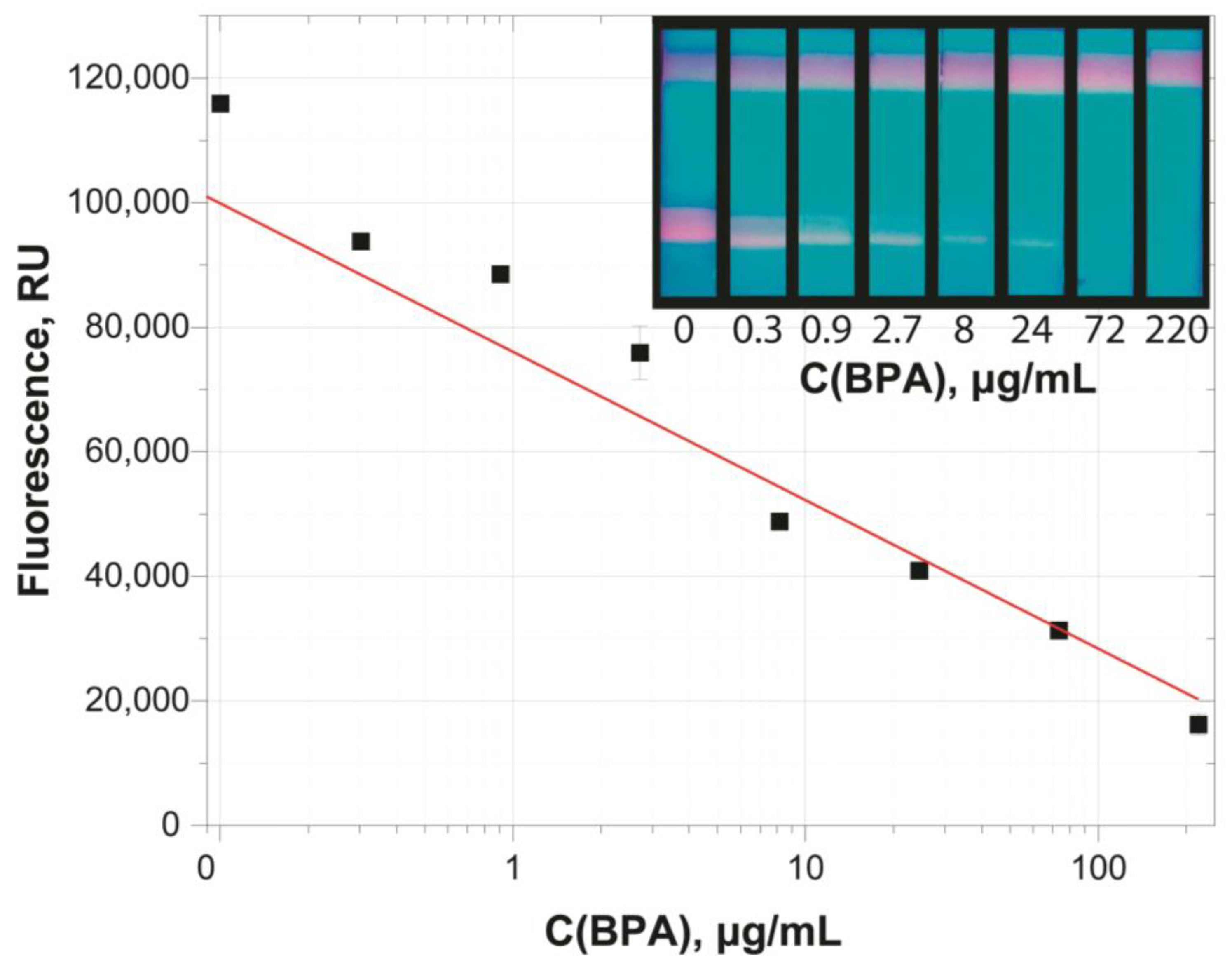

| 0.01 | 123,700 ± 1700 | 99,780 ± 1200 | 83,420 ± 990 | 75,970 ± 840 |

| 0.1 | 99,990 ± 950 | 75,250 ± 1090 | 59,090 ± 1200 | 52,160 ± 1170 |

| 1 | 76,380 ± 780 | 50,900 ± 1300 | 35,500 ± 790 | 27,700 ± 690 |

| BPA Concentration, µg/mL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Concentration of BPA, μg/mL | Without Concentration | Concentration from 1 mL | Concentration from 5 mL | Concentration from 10 mL |

| 0.01 | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 0.099 ± 0.005 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| 0.1 | 0.098 ± 0.007 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 11.4 ± 0.9 | 10 ± 1 |

| 1 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 50 ± 2 | 107 ± 9 |

| Sample Type | Added, µg/mL | Detected, µg/mL | Recovery, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drink water | 3 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 107 ± 8 |

| 1 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 110 ± 9 | |

| 0.3 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 97 ± 5 | |

| Well 1 | 3 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 110 ± 8 |

| 1 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 94 ± 7 | |

| 0.3 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 107 ± 6 | |

| Well 2 | 3 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 103 ± 5 |

| 1 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 104 ± 9 | |

| 0.3 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 100 ± 5 |

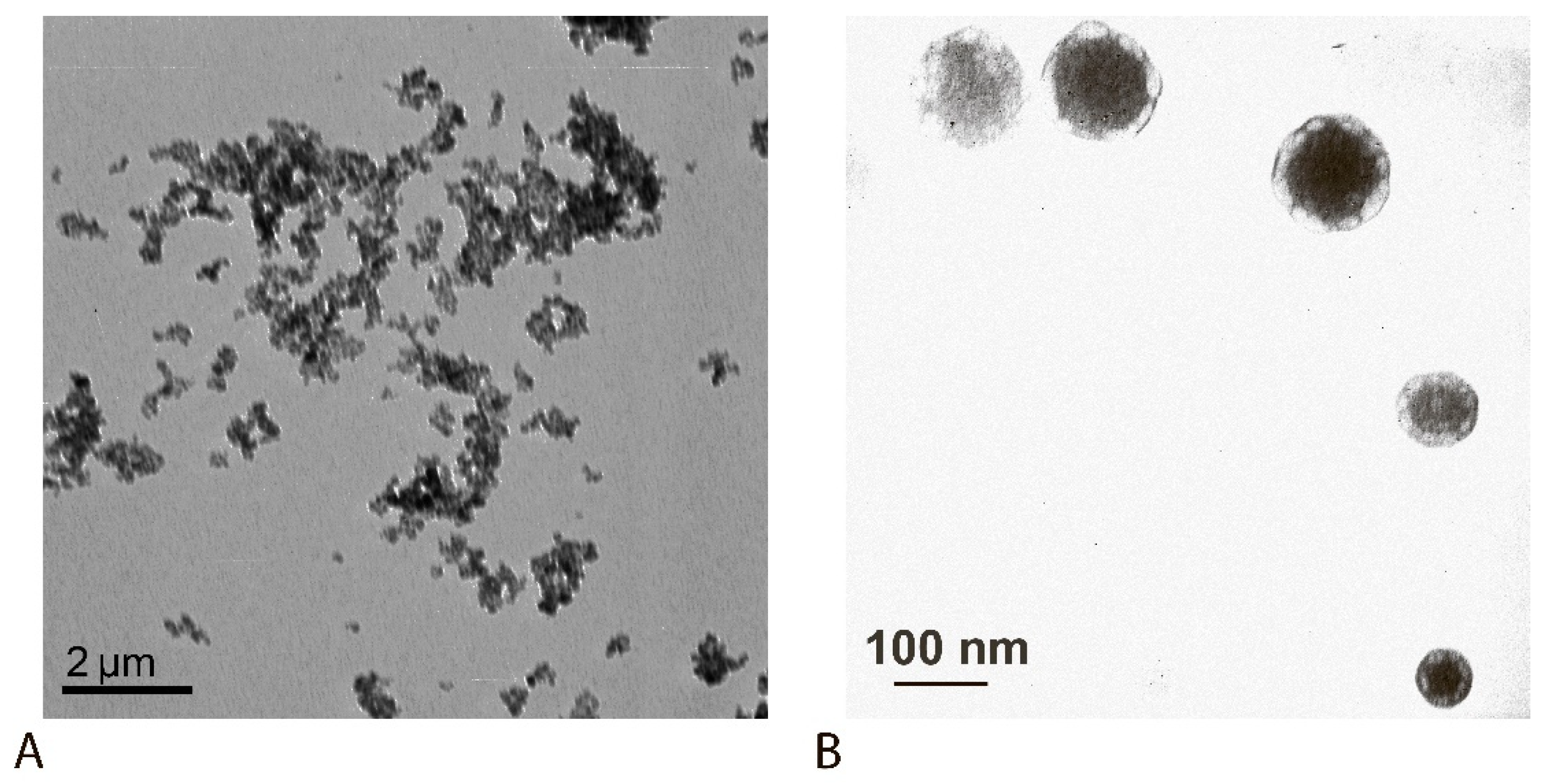

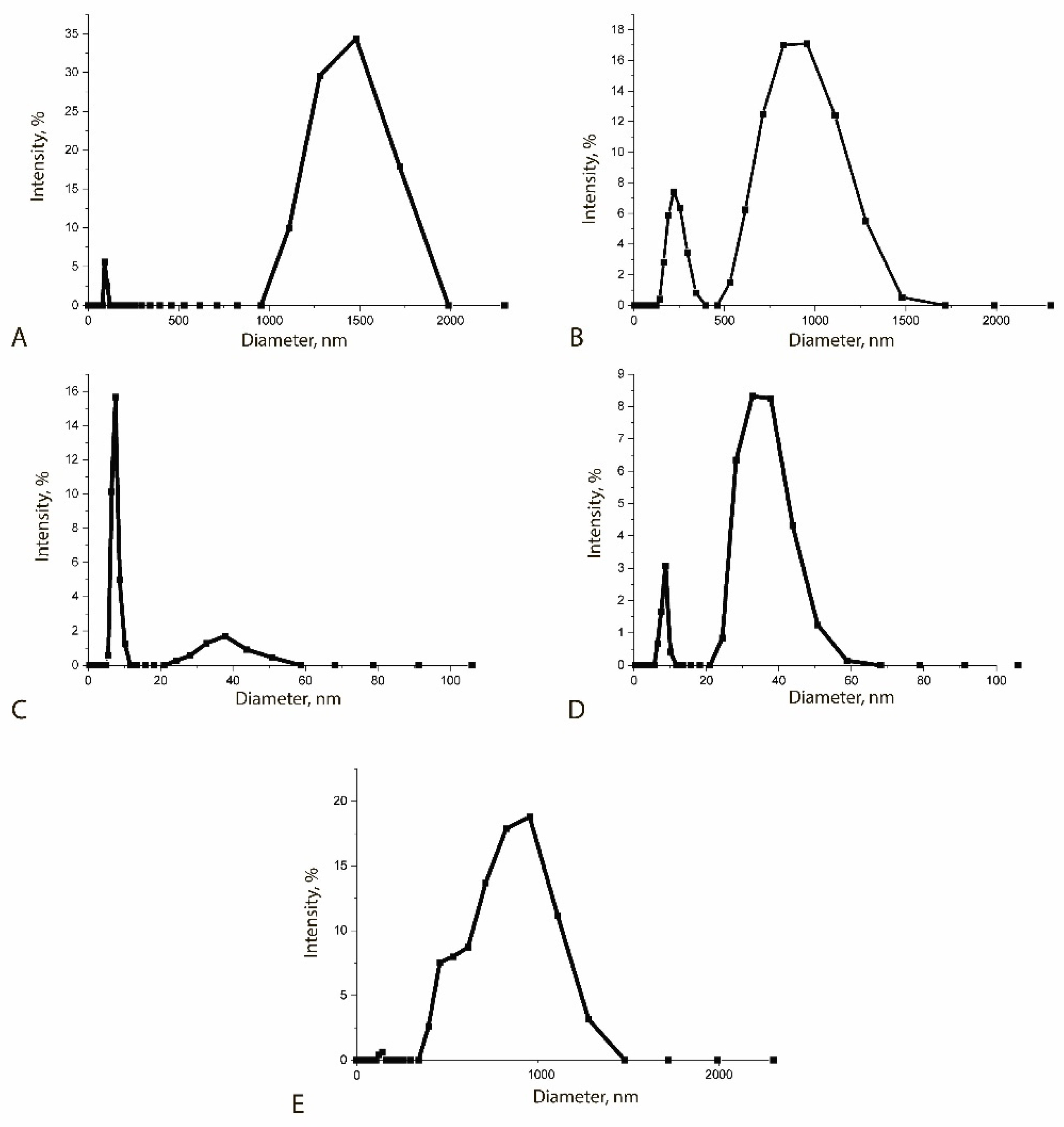

| Sample | Size, nm |

|---|---|

| MPs | 88 ± 10 and 1500 ± 200 |

| MP-PAb | 250 ± 15 and 855 ± 20 |

| QDs | 8 ± 3 |

| QD-Ab | 47 ± 18 |

| MP-PAb–QD-Ab | 838 ± 95 |

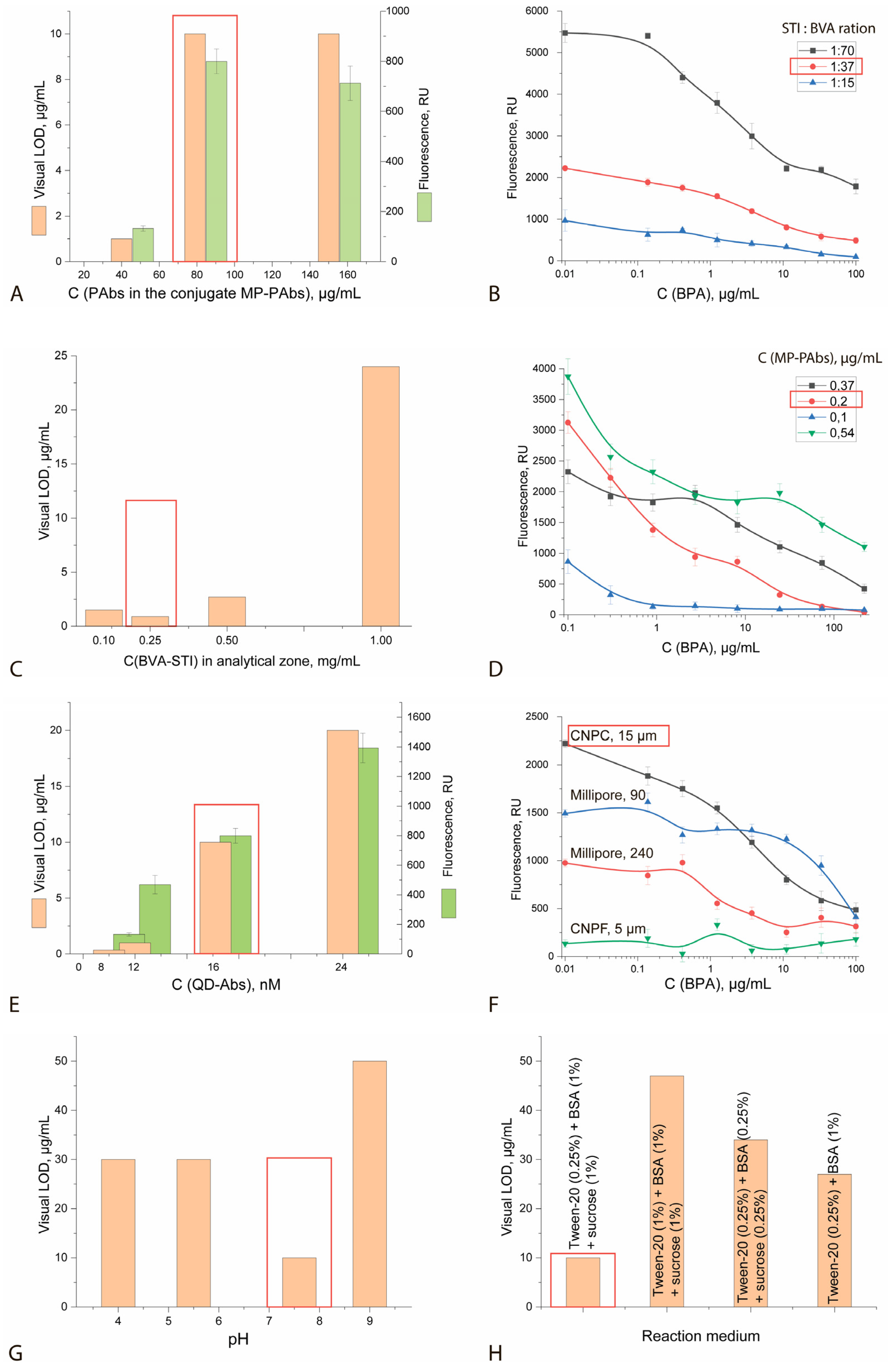

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| PAb concentration in the MP-PAT conjugate | 80 µg/mL |

| SIT:BVK ratio during conjugate synthesis | 1:37 |

| SIT-BVK conjugate concentration applied to the analytical zone | 0.25 mg/mL |

| MP-PAb conjugate concentration | 0.2 mg/mL |

| QD-Ab conjugate concentration | 16 nM |

| Working nitrocellulose membrane | Type CNPC (high protein binding), average pore size: 15 μm |

| Reaction medium pH | 7.6 |

| Reaction medium composition | Tween-20 (0.25%) + BSA (1%) + sucrose (1%) |

| Method | Receptor | Sample Preparation | LOD | Object | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric detection | Without receptor | Standard sample | 1.38 × 10−7 M (31.5 ng/mL) | PC water bottle | [54] |

| Fluorescence sol–gel biochip | Aptamer | Standard sample | 1 pM (0.23 fg/mL) | - | [55] |

| Chemiluminescent system | Aptamer | Standard sample | 1 μM (0.23 μg/mL) | Water | [56] |

| HPLC | Without receptor | Derivatization of the extract | 0.71 pg/mL | - | [57] |

| GC–MS | Without receptor | Derivatization of the extract | 2.0 ng/g | Honey | [58] |

| Capillary electrophoresis | Without receptor | Microextraction | 0.6 mg/mL | Tap water, lake water and seawater samples | [59] |

| LFIA with QDs | Antibody | - | 10 ng/mL | Distilled drinks | [60] |

| LFIA with latex particles | Antibody | Extraction | 0.14 ng/mL | coated papers | [34] |

| LFIA with GNPs | Antibody | - | 0.67 ng/mL | River water | [53] |

| Our work | Antibody | - | 0.3 ng/mL (with preconcentration) | Water | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taranova, N.A.; Bulanaya, A.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Immunofluorescence Rapid Analysis of Bisphenol A in Water Based on Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots. Sensors 2025, 25, 7328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237328

Taranova NA, Bulanaya AA, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Immunofluorescence Rapid Analysis of Bisphenol A in Water Based on Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237328

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaranova, Nadezhda A., Alisa A. Bulanaya, Anatoly V. Zherdev, and Boris B. Dzantiev. 2025. "Immunofluorescence Rapid Analysis of Bisphenol A in Water Based on Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237328

APA StyleTaranova, N. A., Bulanaya, A. A., Zherdev, A. V., & Dzantiev, B. B. (2025). Immunofluorescence Rapid Analysis of Bisphenol A in Water Based on Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots. Sensors, 25(23), 7328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237328