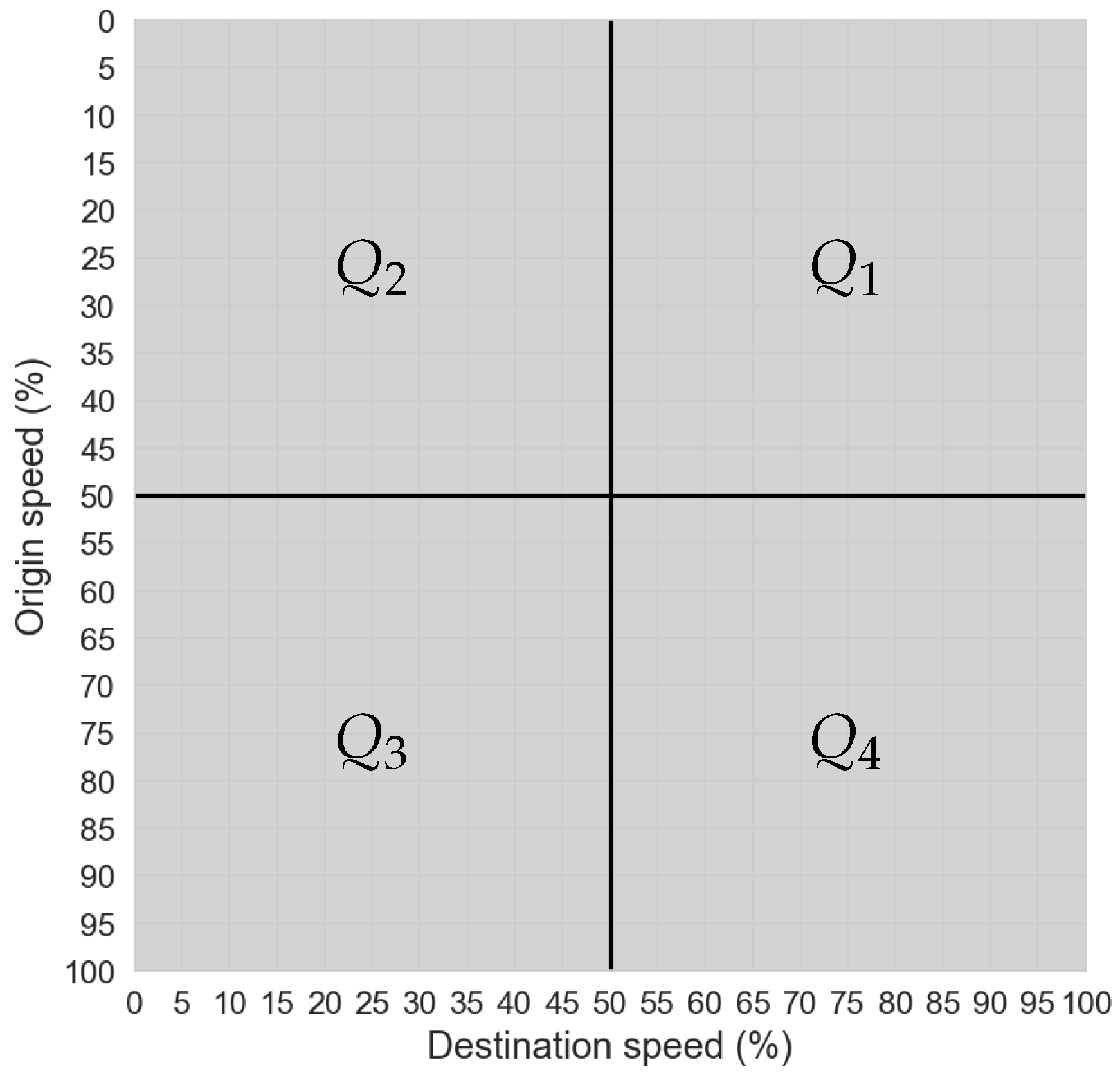

5.1. Simulation Framework

For this research, the open-source software Simulation for Urban MObility (SUMO) version

[

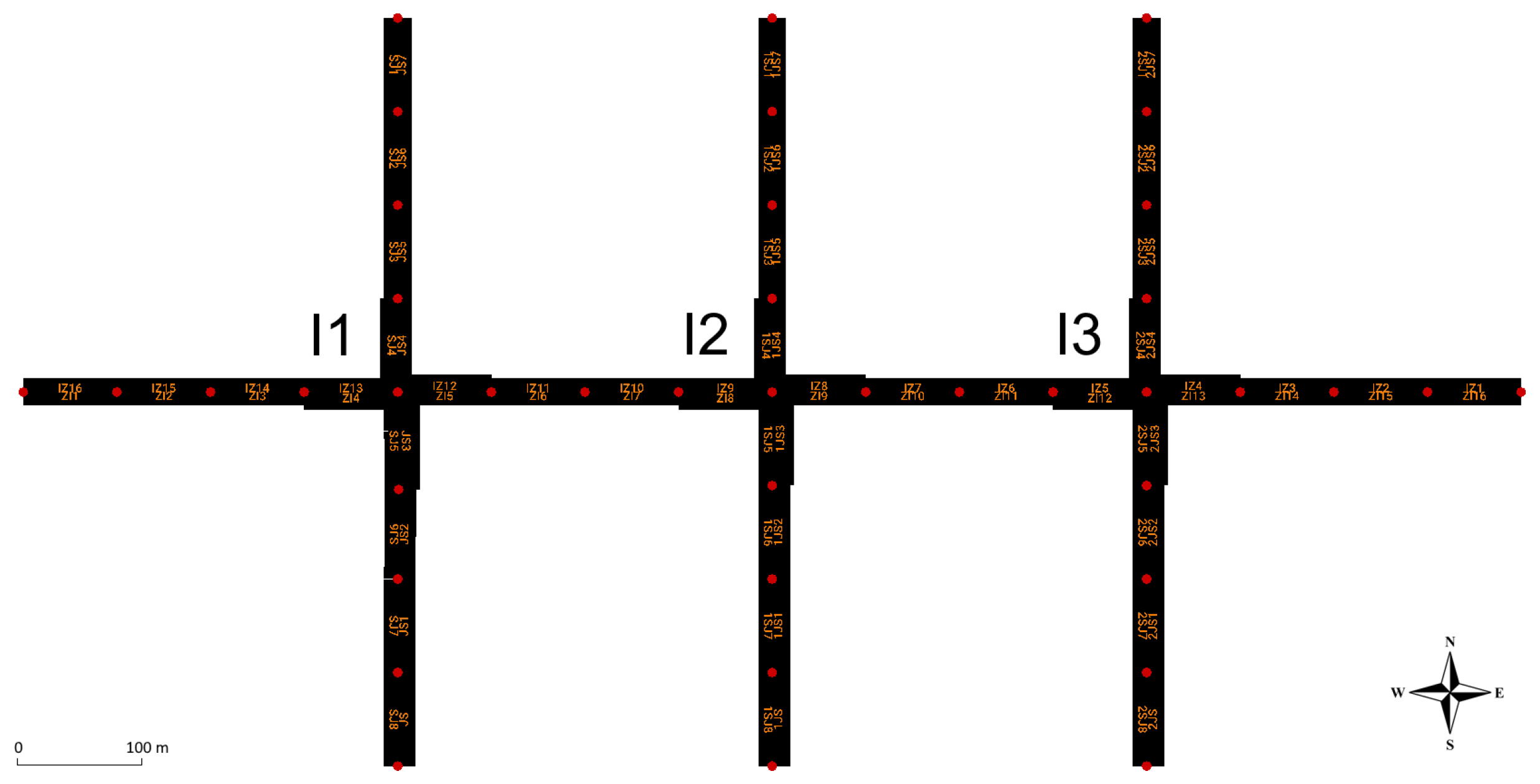

33], combined with the synthetic simulation model shown in

Figure 4, is used. The used synthetic simulation model is inspired by the realistic model of the intersection of King Zvonimir Street and Heinzelova Street used in our previous research [

5,

6]. This intersection is part of the Croatian City of Zagreb’s important urban arterial corridor and represents an average working day from 5:30 to 22:00. Traffic demand for each direction is shown in

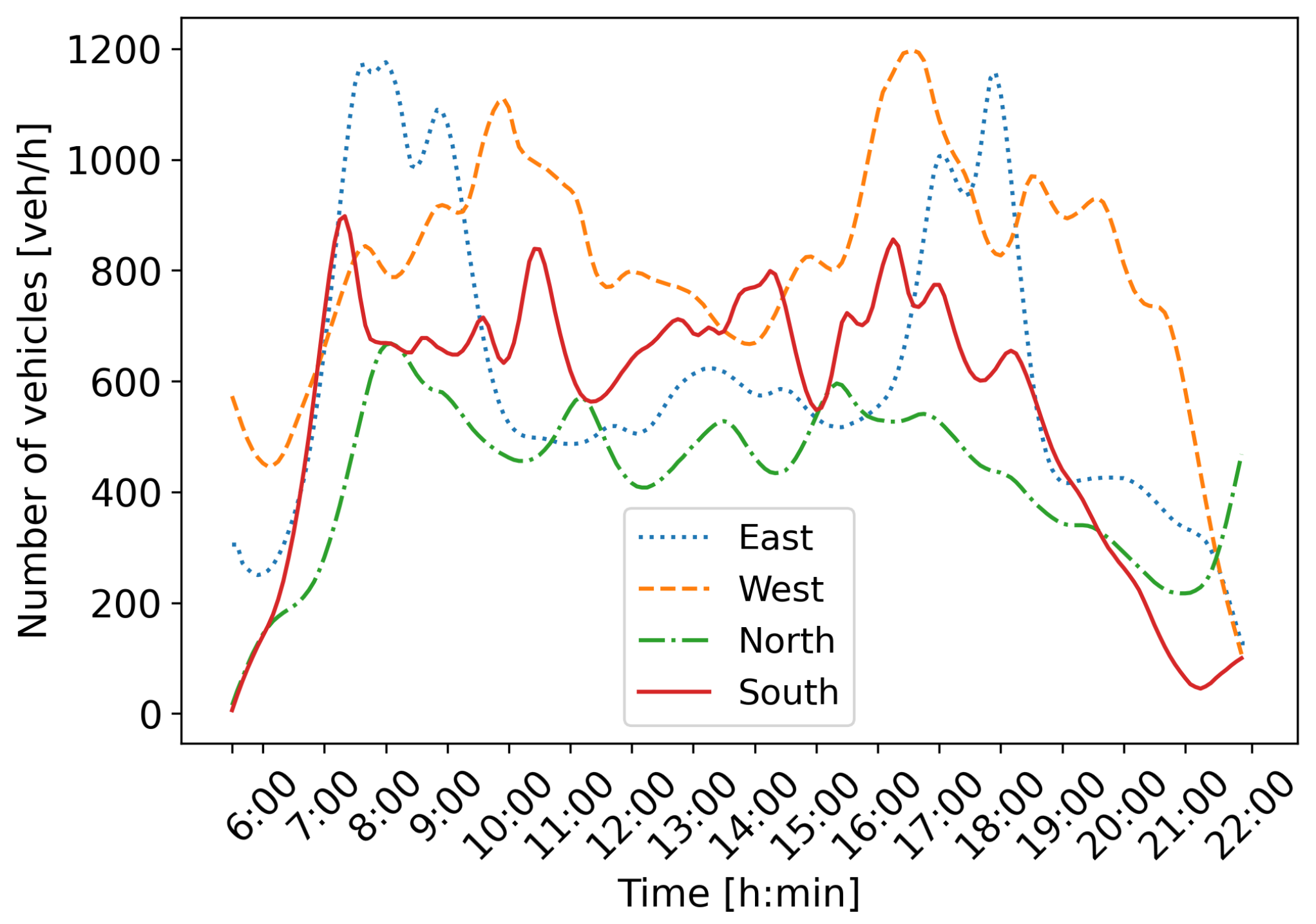

Figure 5.

It can be observed that directions east and west have more pronounced morning and afternoon peak hours. Directions north and south do not have such pronounced peak hours, but the traffic varies during the day. The speed limit is set to 50 km/h, and the intersection operates in the FTSC regime with four signal programs scheduled to activate during the day. Signal programs are activated during an apriori set time period, regardless of traffic state at the intersection. These signal programs are used as actions in our MARL-based ATSC approach.

The synthetic simulation model shown in

Figure 4 is designed with the goal of testing the proposed MARL-based ATSC, where each agent is tasked to control one intersection. Each intersection has four different signal programs that are scheduled to change during the day, and each agent can select one of the existing signal programs for a particular action. Due to the limited traffic data available and the specificity of the proposed method, a synthetic model consisting of three connected consecutive intersections was created for the proof of concept. According to graph theory, three consecutive intersections form a small intersection network [

34]. This model facilitates the interpretation of results and the detection of possible issues.

As mentioned, the simulation used the default car-following model with the and settings adopted to adjust to the local vehicle behavior. The setting defines the eagerness for following the obligation to keep right. This value is set to to force the vehicles to use more lanes, instead of just following the right lane until they have to turn left or right. The parameter is also set to . This parameter defines the driver imperfection, where the value 0 denotes perfect driving; thus, the value is chosen to simulate human driver behavior.

The simulation model used in this research is a synthetic small network of intersections developed based on a realistic reference scenario, primarily intended to provide proof of concept for the proposed STM-based MARL framework. Thus, standard accuracy metrics concerning real-world traffic data are not directly applicable, because the network and vehicle flows were designed synthetically rather than calibrated against the on-site measurements. Nevertheless, the model parameters (e.g., car-following, lane-changing, and driver behavior settings) were selected to reflect realistic vehicle behavior, ensuring that the simulation results provide meaningful insights into the performance of the proposed approach.

5.3. Obtained Results

This section presents the obtained results given for each intersection separately, and an overall overview of the controlled intersection network performance. The presented results are obtained after 500 simulations of training. Performance is measured as timeLoss and queue length , obtained from the SUMO simulator through the traCI interface. The timeLoss parameter measures how much time the vehicle lost due to driving slower than desired and is measured in seconds .

Figure 7 shows the obtained results for the intersection

for both MARL approaches: the reward sharing approach presented in

Figure 7a, and the reward sharing approach presented in the

Figure 7b. The

x-axis denotes the time of the day, and the

y-axis denotes timeLoss value in seconds. At this intersection, it can be observed that FTSC is outperformed by the RL agents. Compared to independent agents and FTSC, reward sharing achieved better performance during the morning and afternoon peak hours.

Performance analysis for the different cooperation strategies is shown in

Table 2. It can be observed that the reward-sharing approach outperformed FTSC as well as independent agents. Reward sharing achieved 1.2

mean (

) timeLoss, standard deviation (

) 1.91

, and max value 10.56

. Independent agents also reduced the mean timeLoss value to 1.75

,

value to 3.30

, and max value to 16.59

. Independent agents improved performance, but the standard deviation indicates performance inconsistency. Compared to FTSC and independent agents, the reward-sharing method shows the best overall efficiency and stability in reducing lost time, which makes it the most reliable approach of the three analyzed.

The results obtained for the independent agents approach regarding intersection

are presented in

Table 2. Results indicate that the independent agent approach achieves improvement over the FTSC, with the mean value of the parameter timeLoss decreasing as the CV penetration rate increases. Although the timeLoss decreases,

remains relatively high, indicating the lower stability of the MARL system.

Table 3 shows the results of the reward-sharing approach for intersection

. The obtained results indicate significantly better performance compared to the independent agents and the FTSC system. The

value tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases. The standard deviations are lower in all phases than in the independent agents approach, indicating better stability and predictability of the MARL system behavior. These results show that reward sharing encourages cooperative behavior among agents, which results in reduced timeLoss.

A graphical comparison of the performance metrics on the middle intersection

is shown in

Figure 8. It can be observed that during the morning peak hour, reward sharing achieved better performance, as shown in

Figure 8b, while the independent agents approach performed close to FTSC, as shown in

Figure 8a. During afternoon peak hour, both the reward sharing and independent agents achieved better performance compared to the FTSC approach.

Performance analysis for the independent agents approach is shown in

Table 4. It can be observed that independent agents outperformed FTSC. The obtained results indicate that the

value tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases. However,

values show that the system has some variability in its performance, indicating lower stability of the MARL system.

Performance analysis for the shared approach is shown in

Table 5. It can be observed that reward sharing outperformed FTSC. Compared to the independent approach, reward sharing achieved even better performance. The obtained results indicate that the

value tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases. However,

values are lower compared to FTSC and the independent agents approach, which indicates higher stability of the MARL system.

Figure 9 shows a graphical representation of the achieved timeLoss at the intersection

. The obtained results indicate that the reward-sharing approach shown in

Figure 9b achieved better performance compared to FTSC and independent agents, as shown in

Figure 9a. During afternoon hours, both MARL ATSC approaches performed better than FTSC.

A performance analysis for the independent agents approach at the intersection

is shown in

Table 6. Obtained results show that the

value decreases as the CV penetration rate increases, while

indicates that the MARL system has notable variability in its performance.

A performance analysis for the reward-sharing approach at the intersection

is shown in

Table 7. Compared to FTSC and the independent agents approach, this approach achieved even better results. Although the

value does not decrease significantly, the reward-sharing approach has better stability, which can be observed from

values that are very consistent throughout CV penetration rate range.

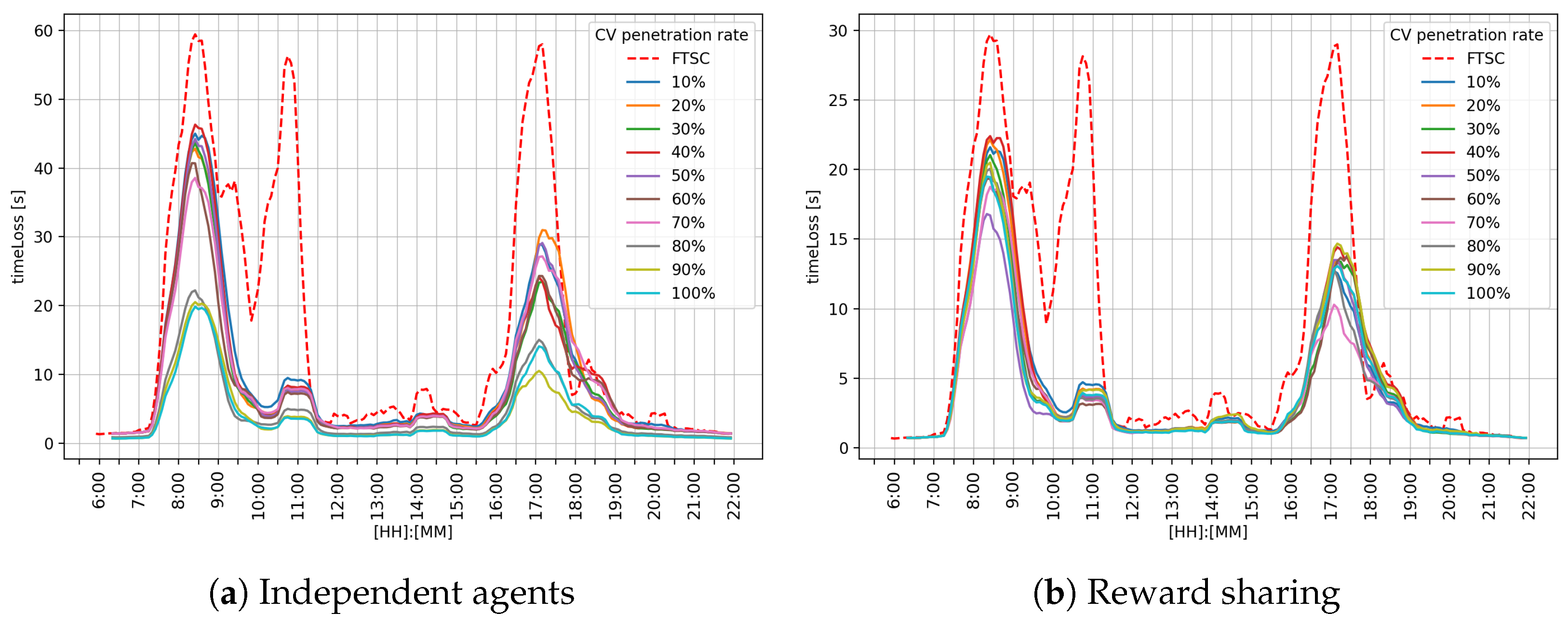

Figure 10 shows the overall performance for the intersection network. The graph in

Figure 10 shows that the reward-sharing approach shown in

Figure 10b achieved better results than FTSC and independent agents, as shown in

Figure 10a. Both independent agents and the reward-sharing approach alleviated the morning and afternoon peak hours. The most significant difference is a reduction in the peak that appears around 10:30, where MARL ATSC systems have almost eliminated it.

Table 8 shows an analysis of the overall performance of the independent agents approach for the analyzed intersection network. The obtained results indicate that the

value decreases as the CV penetration rate increases, with a significantly better result achieved above the

penetration rate. Relatively high

values indicate that the ATSC system is not very stable.

Table 9 shows an analysis of the overall performance of the independent agents approach for the analyzed intersection network. The obtained results indicate that the

value decreases as the CV penetration rate increases, with a significantly better result achieved above the

penetration rate. Relatively high

values indicate that the ATSC system is not very stable.

The influence of the CV penetration rate was tested on 500 simulations, and timeLoss and queue length parameters were selected as performance metrics. A setting of 500 simulations is selected because cooperation parameter k showed the greatest impact on the learning system after 500 simulations, when the RL system already converged.

5.3.1. Analysis of the TimeLoss Parameter

Figure 11 shows a comparison of the timeLoss parameter across learning episodes for two MARL approaches:

Figure 11a, a system with independent agents, and

Figure 11b, a system with reward sharing. In both cases, the impact of different CV penetration rates is observed, with the dashed red line being a reference representing the performance of conventional FTSC. In both approaches, a rapid decrease in timeLoss is observed during the first 100 episodes, after which the system reaches a steady state. However, larger oscillations are observed between episodes and between different CV penetration rates in the independent agents approach, as shown in

Figure 11a, indicating greater variability in the behavior of agents learning independently.

In the case of a reward-sharing system, as shown in

Figure 11a, oscillations between episodes are less pronounced; thus, the system shows more robust behavior at different CV penetration rates. These results indicate that the introduction of the reward-sharing mechanism contributes to a more efficient learning process and more coordinated traffic control, thus achieving more stable and reliable TSC compared to the independent agents approach.

Table 10 presents the descriptive statistics of the timeLoss parameter for the independent agents approach. The results are collected for different CV penetration rates ranging from

to

and for FTSC without CVs. For the independent agents approach, the

values have a reducing trend as the CV penetration rate increases. The results show moderate

values, which indicates the presence of variability in the ATSC system.

The results obtained for the reward-sharing approach are presented in

Table 11, where

timeLoss values are reduced above a

CV penetration rate, while the

remain consistently low towards the end of the penetration range, confirming the improved robustness of the system introduced with reward sharing between the agents.

Thus, while the reward-sharing approach does not substantially reduce the average timeLoss compared to independent agents, it improves system stability and robustness by reducing performance fluctuations across episodes and CV penetration rates.

5.3.2. Analysis of the Queue Lengths

Table 12 shows descriptive statistics of queue length for the independent agents approach. Analysis of the queue length parameter for the independent agents approach at the intersection

shows that the queue length tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases, with the lowest values at the

CV penetration rate. However, the

indicates variability between episodes, suggesting the sensitivity of the system to intersection network dynamics. Thus, the decreasing trend of queue length indicates that a higher CV penetration rate can contribute to a better performance of the MARL ATSC.

Table 13 shows the results of the queue length for the reward-sharing approach. Analysis shows that the queue length tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases, with the lowest values at the

CV penetration rate. However, the

indicates less variability between episodes compared to the independent agents approach, suggesting that the shared learning approach is more robust to variations in the traffic demand, which is expected.

Results of queue length on intersection

for the independent agents learning approach are presented in

Table 14. The lowest values are reached at the

CV penetration rate. However,

values indicate variability in the system performance. This approach successfully reduces queue lengths compared to FTSC but shows limitations in the performance consistency over different penetration rates.

Table 15 shows the results of the reward-sharing approach for the same intersection

. Compared to the independent agents, the reward-sharing approach shows more uniform and stable results. The

values are significantly lower than the FTSC reference value, with a slight improvement trend towards the end of the CV penetration range. The standard deviations are low for all analyzed penetration rates, indicating better stability of the ATSC system.

Table 16 shows the results of the queue length at the intersection

for the independent agents approach. Compared to the FTSC, the independent agents approach achieves a significant reduction in queue length. The lowest values are recorded around 50–

penetration rate, when the system achieves the lowest queue length and

values. However, slight variability towards the end of penetration range indicates that the system occasionally deviates from the optimum, which may be due to a lack of coordination among the agents.

Table 17 shows the results of the queue length at the intersection

for the independent agents approach. Compared to the FTSC, the independent agents approach achieves a significant reduction in queue length. The lowest values are recorded around 50–

penetration rate, when the system achieves the lowest queue length and

values. However, slight variability towards the end of penetration range indicates that the system occasionally deviates from the optimum, which may be due to a lack of coordination among the agents.

5.3.3. Seed Analysis

Seed analysis is conducted by generating 10 new seeds for each penetration rate ranging from

to

. Analysis is conducted for the independent agents approach as well as the reward-sharing approach.

Table 18 shows an analysis of the timeLoss parameter for different seeds for the independent agents approach. Each penetration rate is tested with 10 different seeds on MARL ATSC. The obtained results show that different seeds have no significant influence on the MARL ATSC system performance. The obtained results indicate that the

value of timeLoss is reduced as the CV penetration rate increases.

Table 18 shows that the

value tends to decrease as the CV penetration rate increases, with the best results towards the end of CV penetration range. The decreasing

value with relatively small

value indicates that the independent agents approach is robust to unseen scenarios of different seeds.

Table 19 shows descriptive statistics of the timeLoss parameter for different seeds on the reward-sharing approach. Obtained results indicate that the ATSC system has the best performance around

CV penetration rate. The

value is relatively small, indicating that the shared learning approach is robust to variations in the traffic demand of different seeds.

The analysis shows that the reward-sharing approach ensures relatively stable performance, with little oscillations in performance. Although the values vary across different CV penetration rates, the variation is generally small, suggesting robustness of the MARL ATSC and robustness to new scenarios.