Portable Multispectral Imaging System for Sodium Nitrite Detection via Griess Reaction on Cellulose Fiber Sample Pads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation for Standard Reagent Solutions

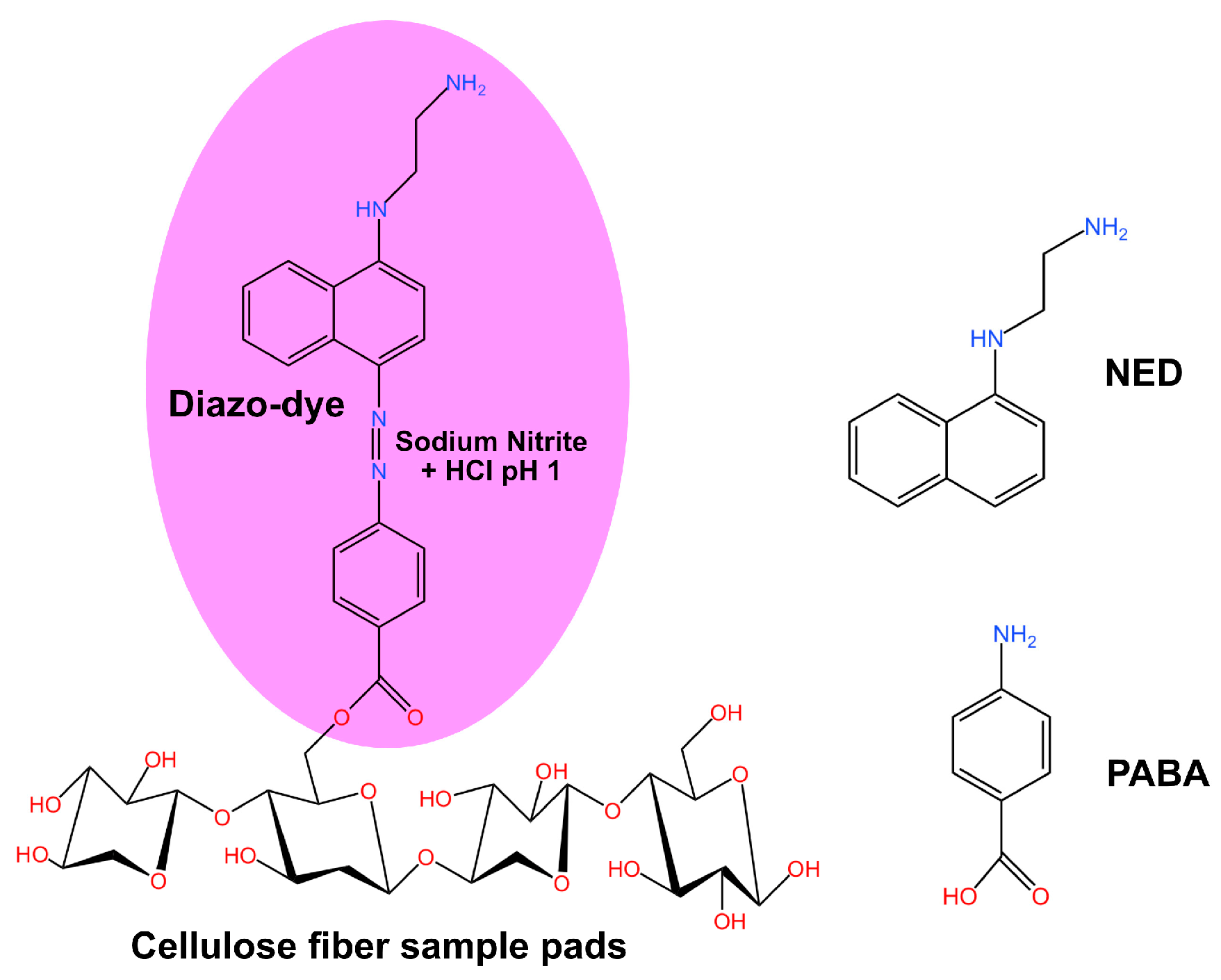

2.2. Characterization of SA-NED and PABA-NED Griess Reactions Using UV-VIS Spectrometer

2.3. Specificity Test of PABA-NED Griess Reaction

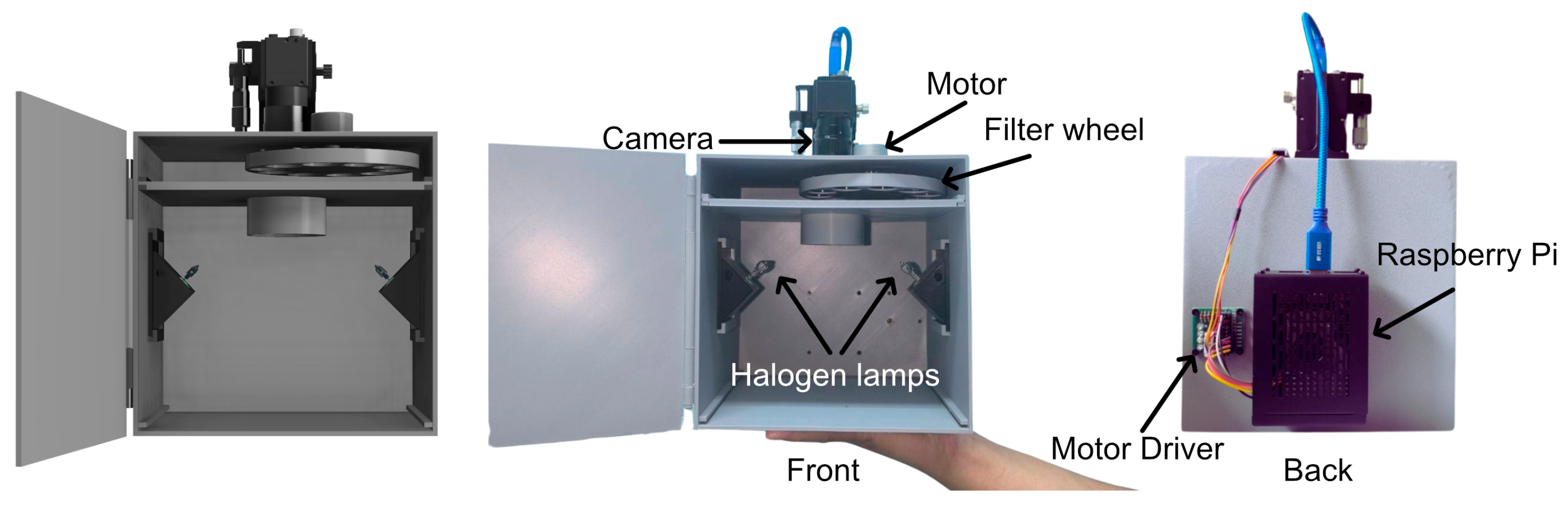

2.4. Custom-Built Multispectral Imaging System

2.5. Sample Preparation for Paper-Based PABA-NED Nitrite Detection Kit

2.6. Image Acquisition and Data Analysis Methods

2.7. Smartphone-Based RGB Imaging and Comparative Validation

2.8. Image Segmentation and Classification Strategy

3. Results and Discussion

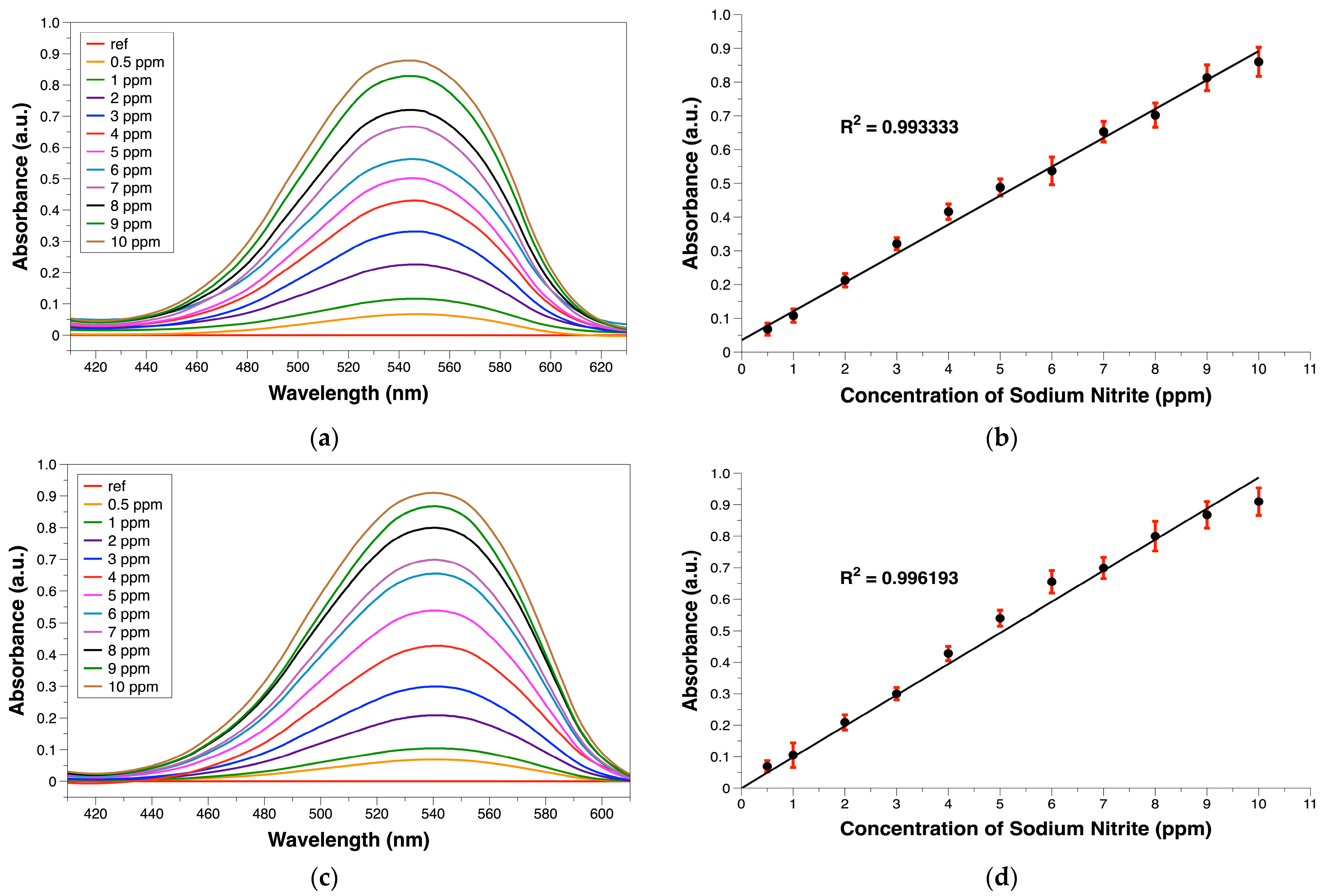

3.1. Comparison of PABA-NED and SA-NED Spectral Characteristics

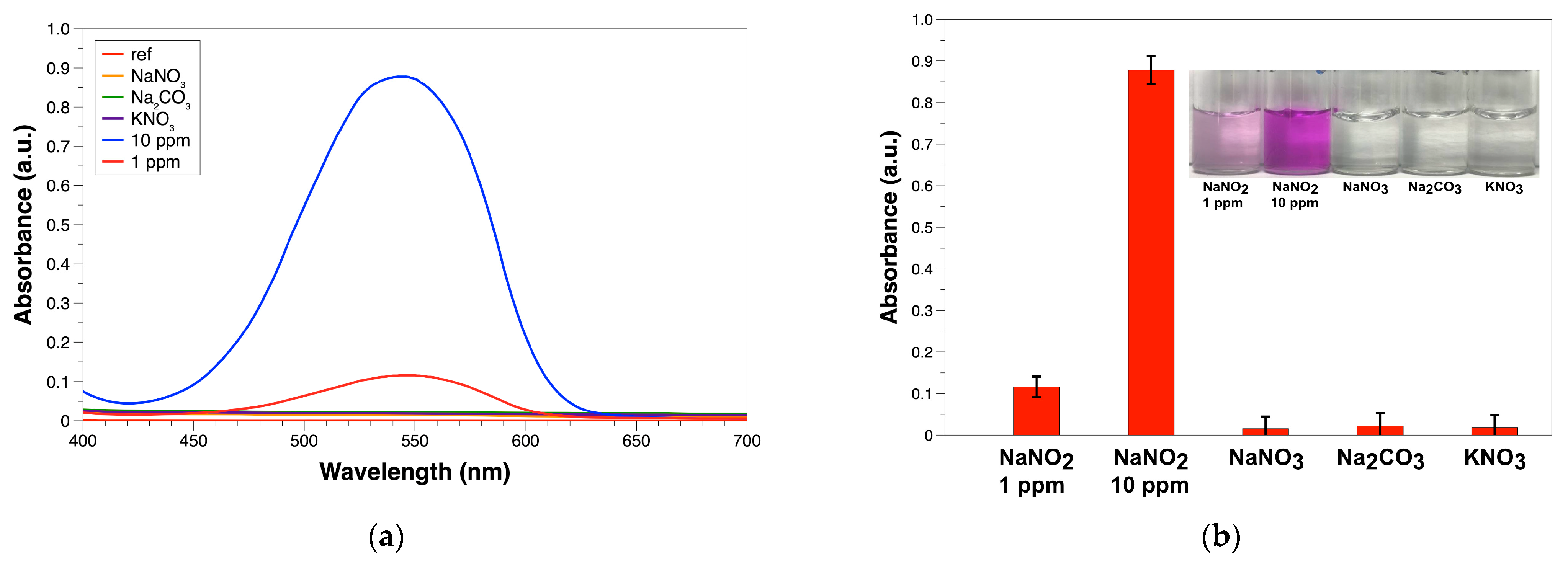

3.2. Selectivity of the PABA-NED Griess Reaction

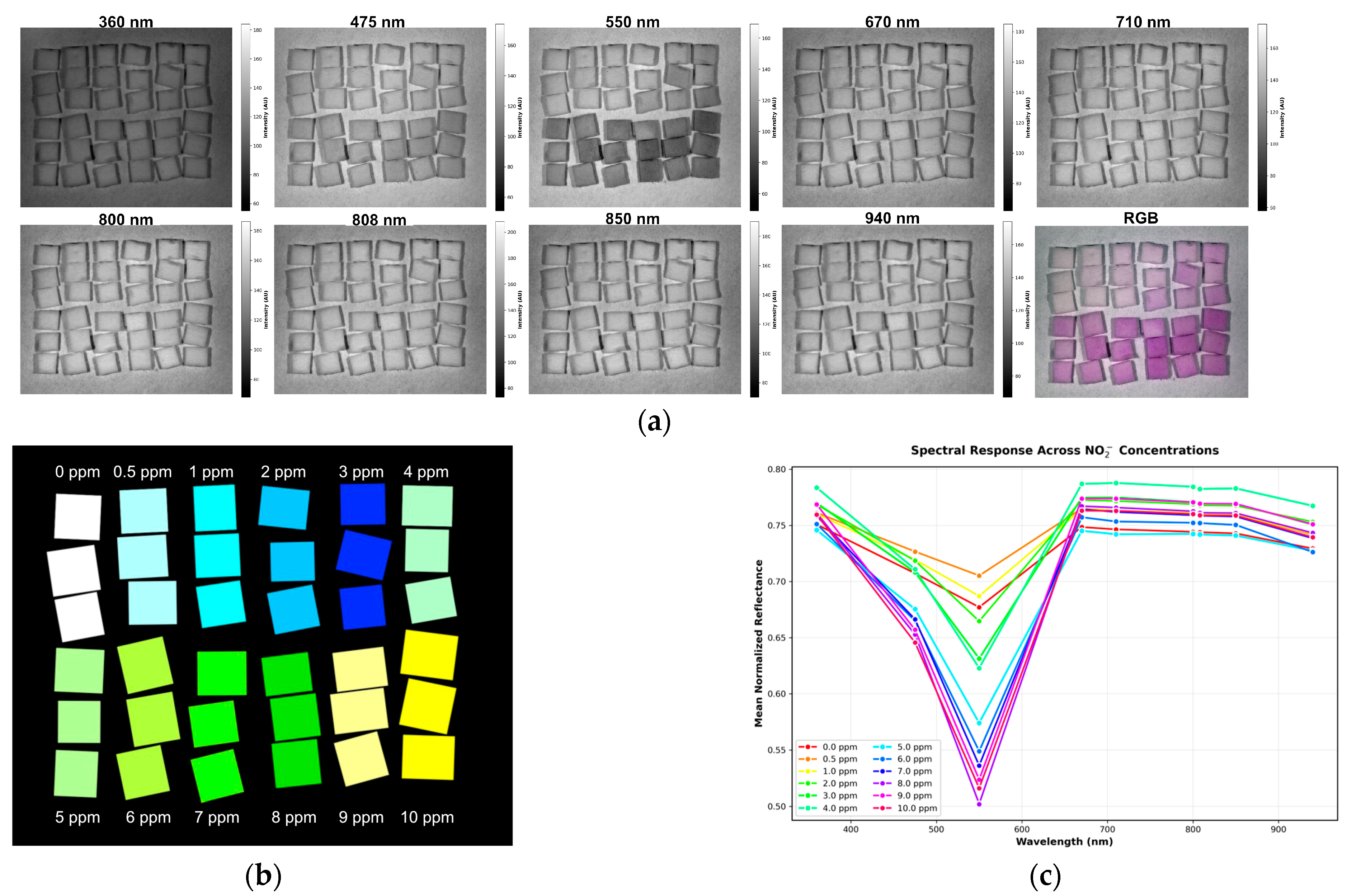

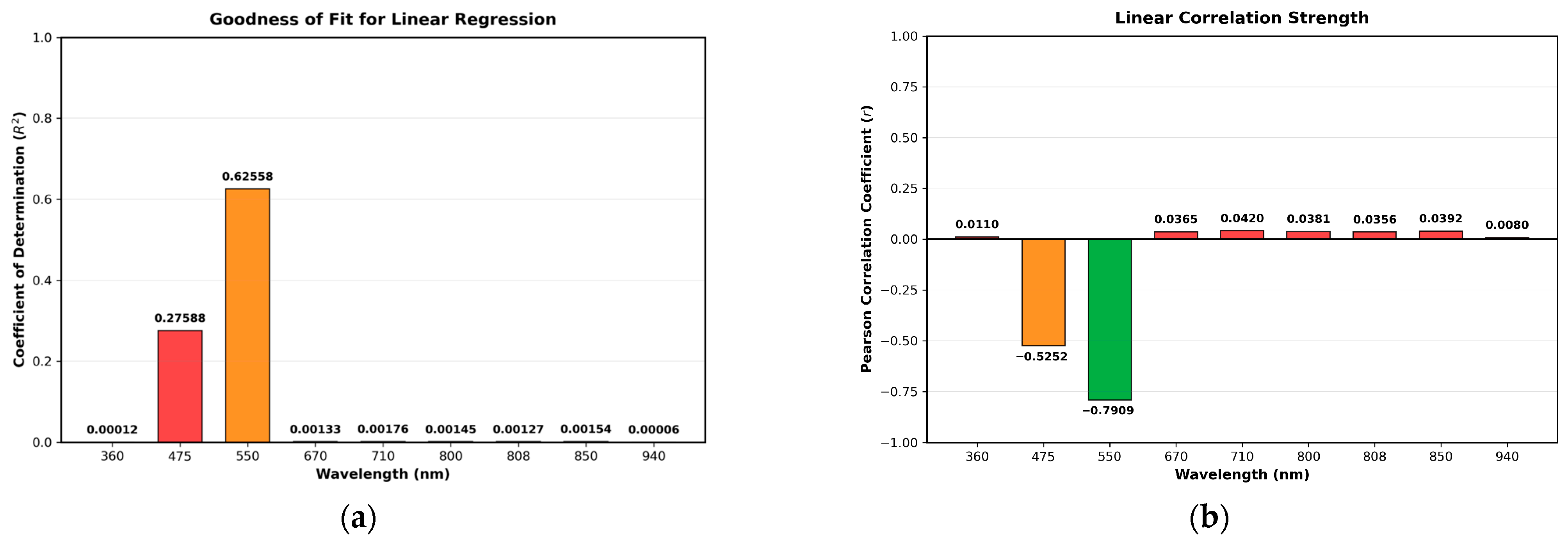

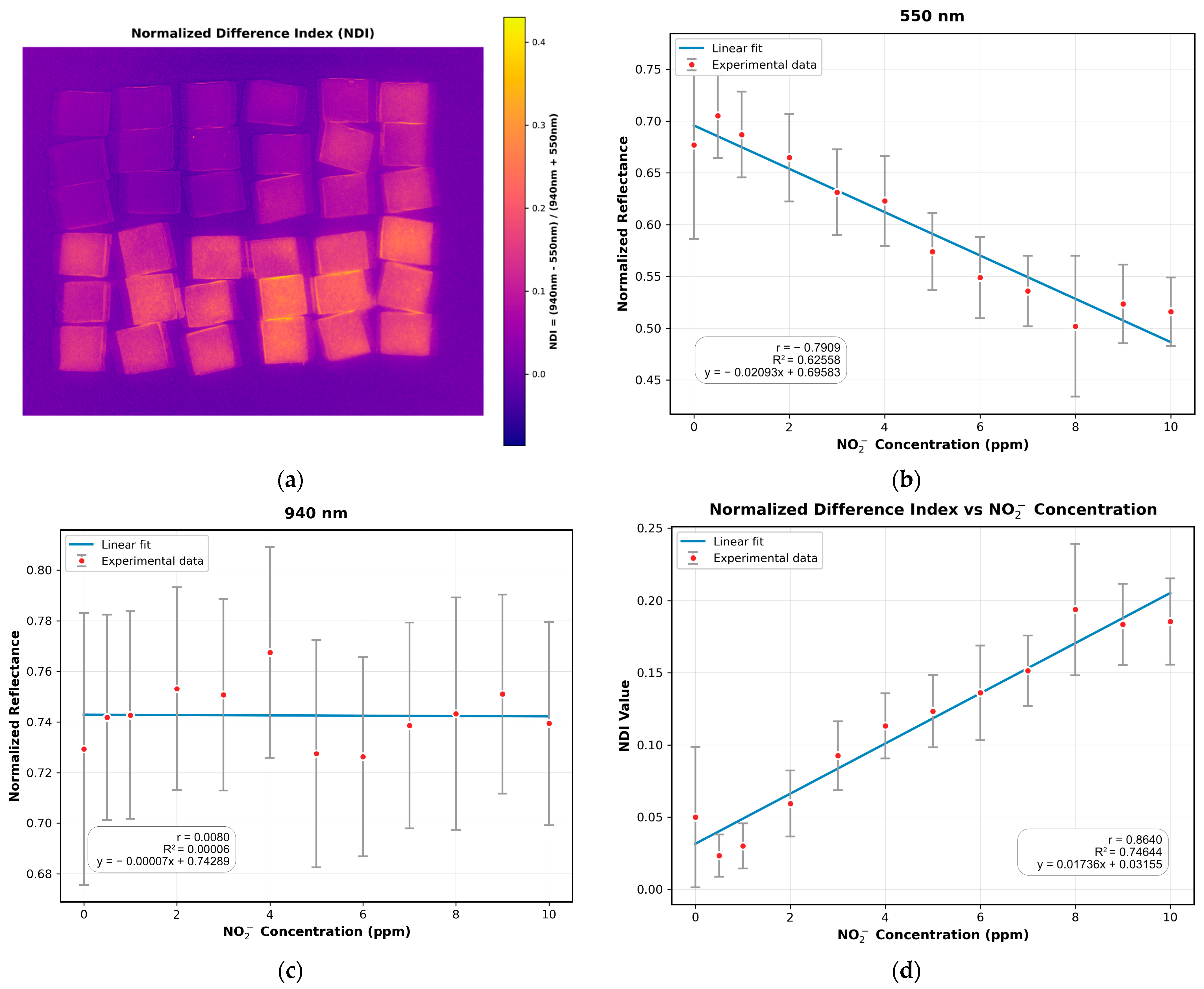

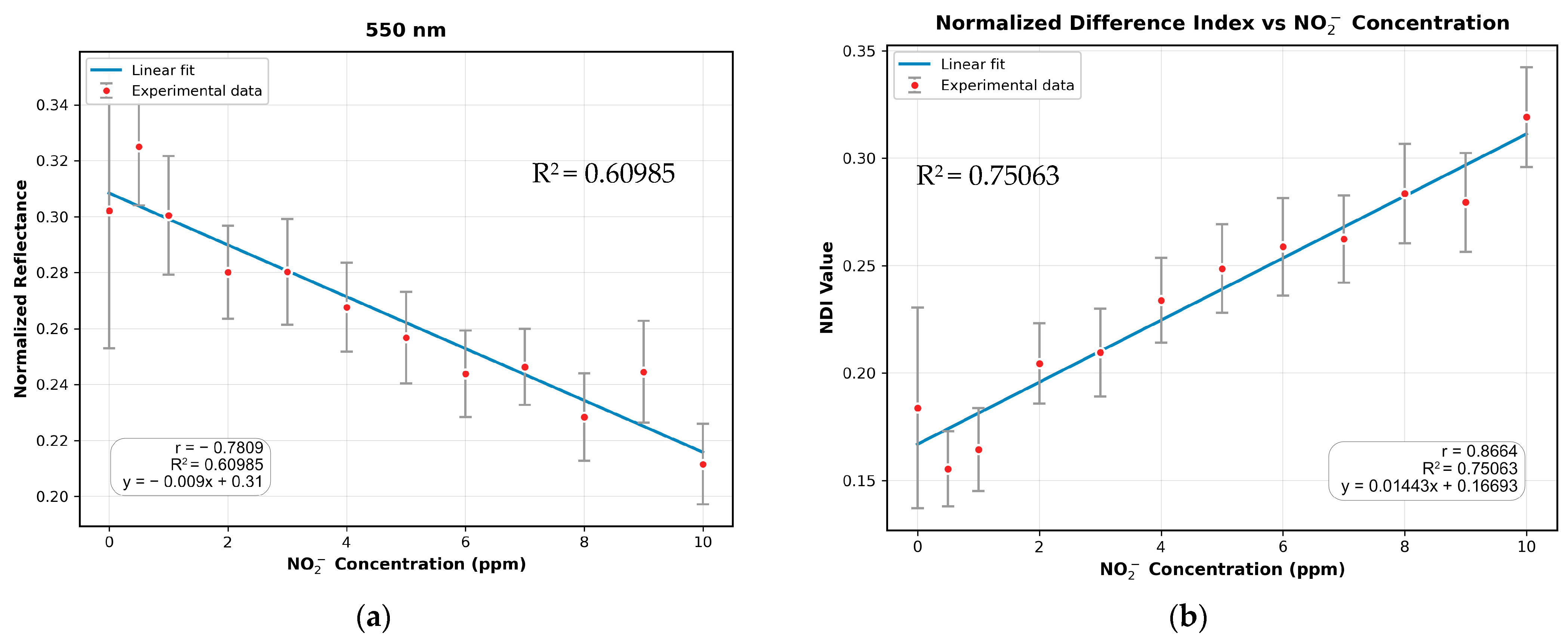

3.3. Absorption Study with the MSI System

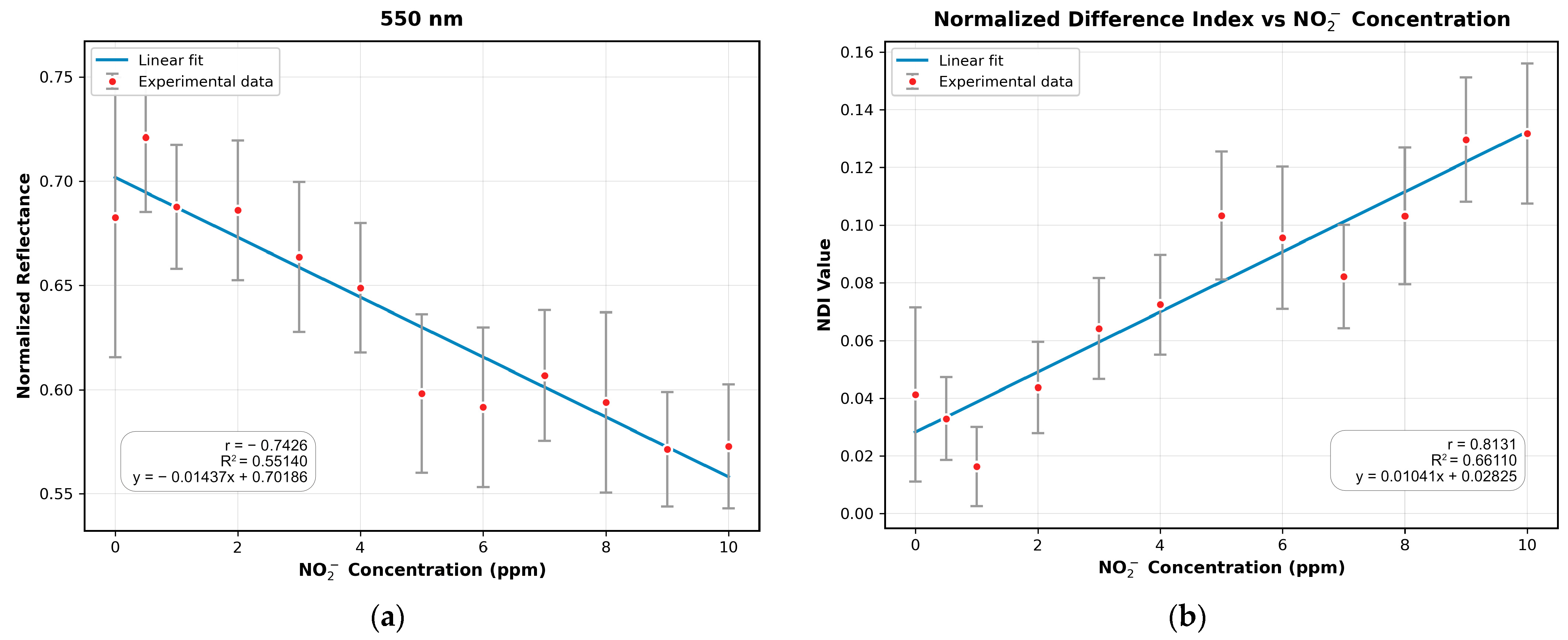

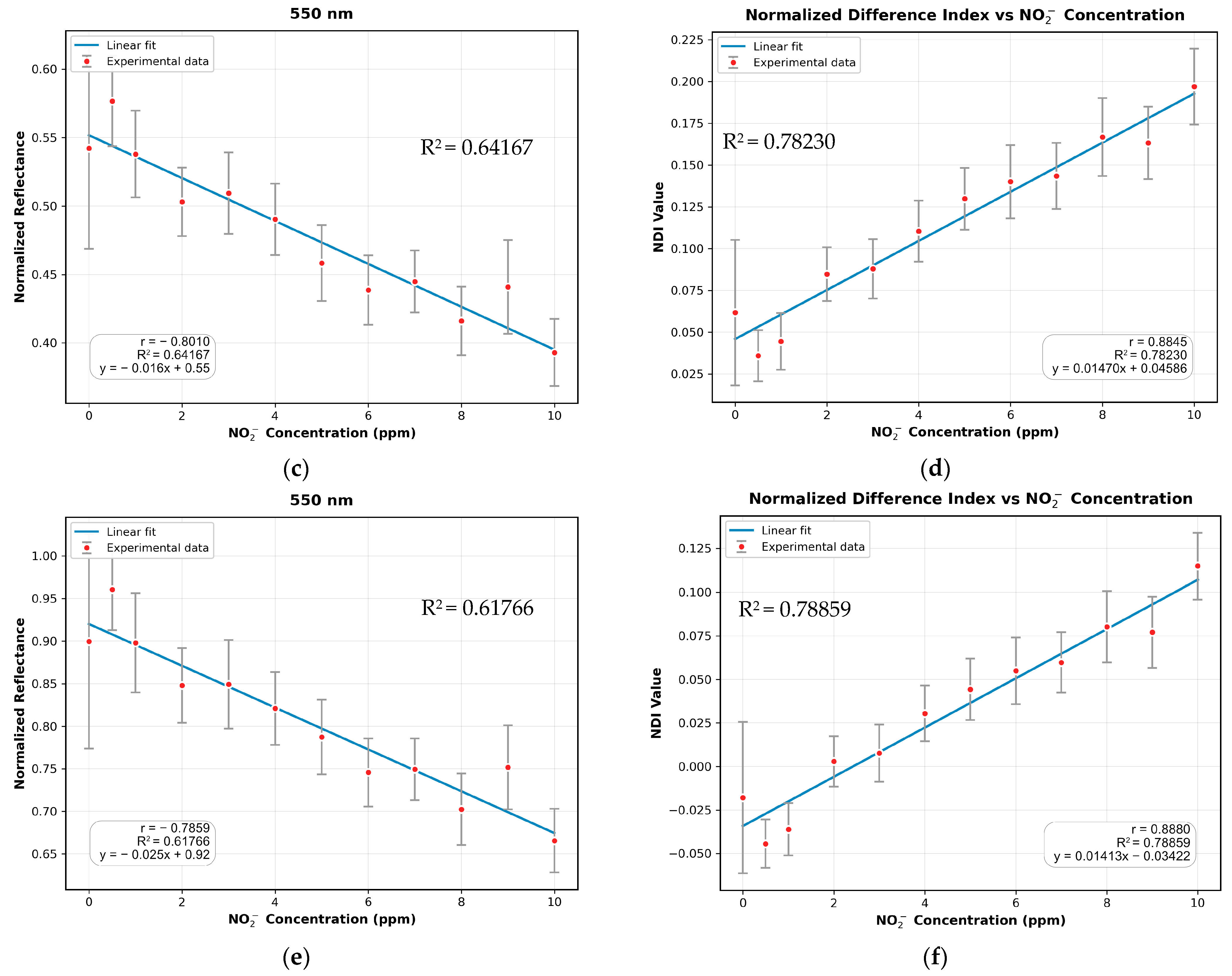

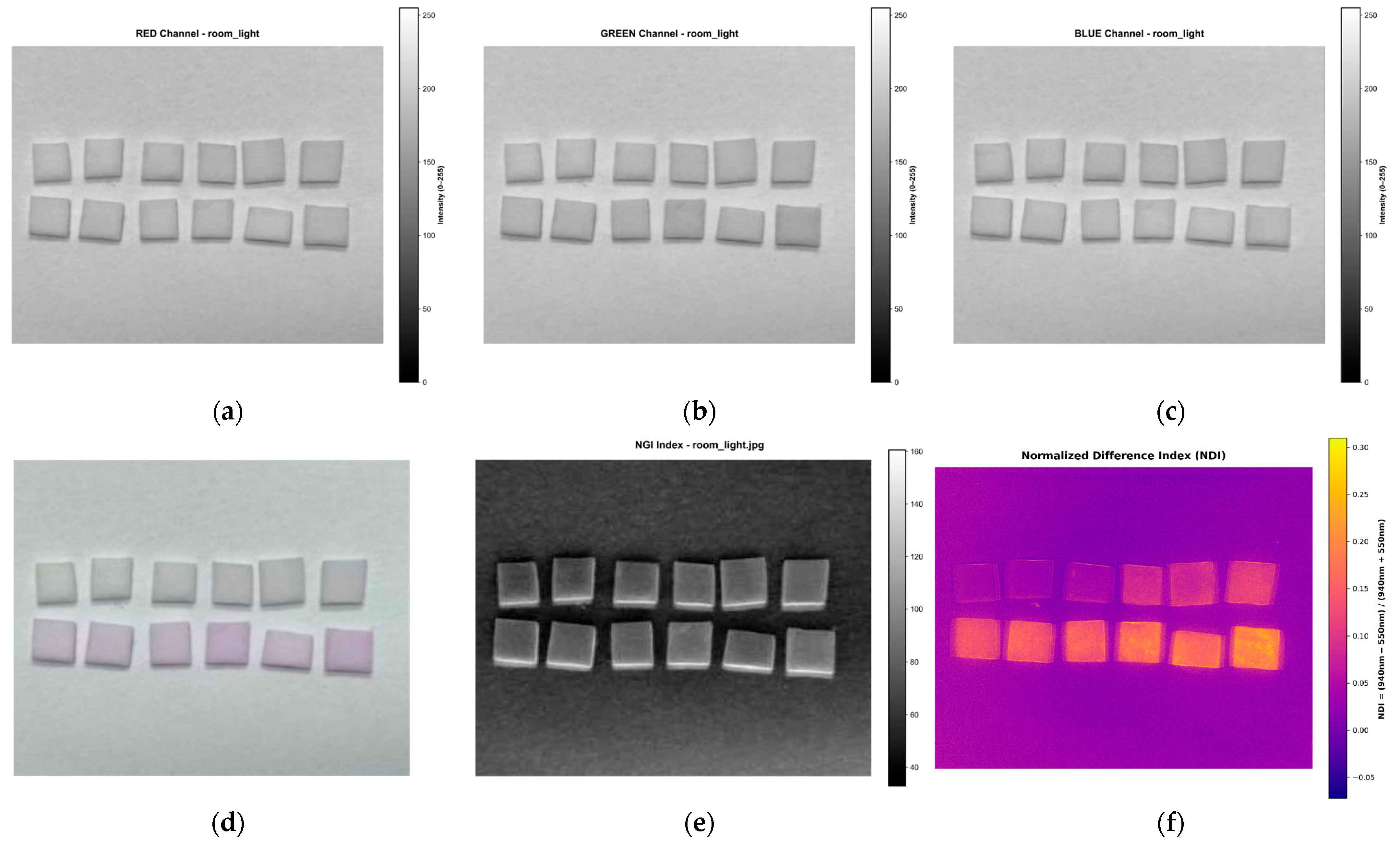

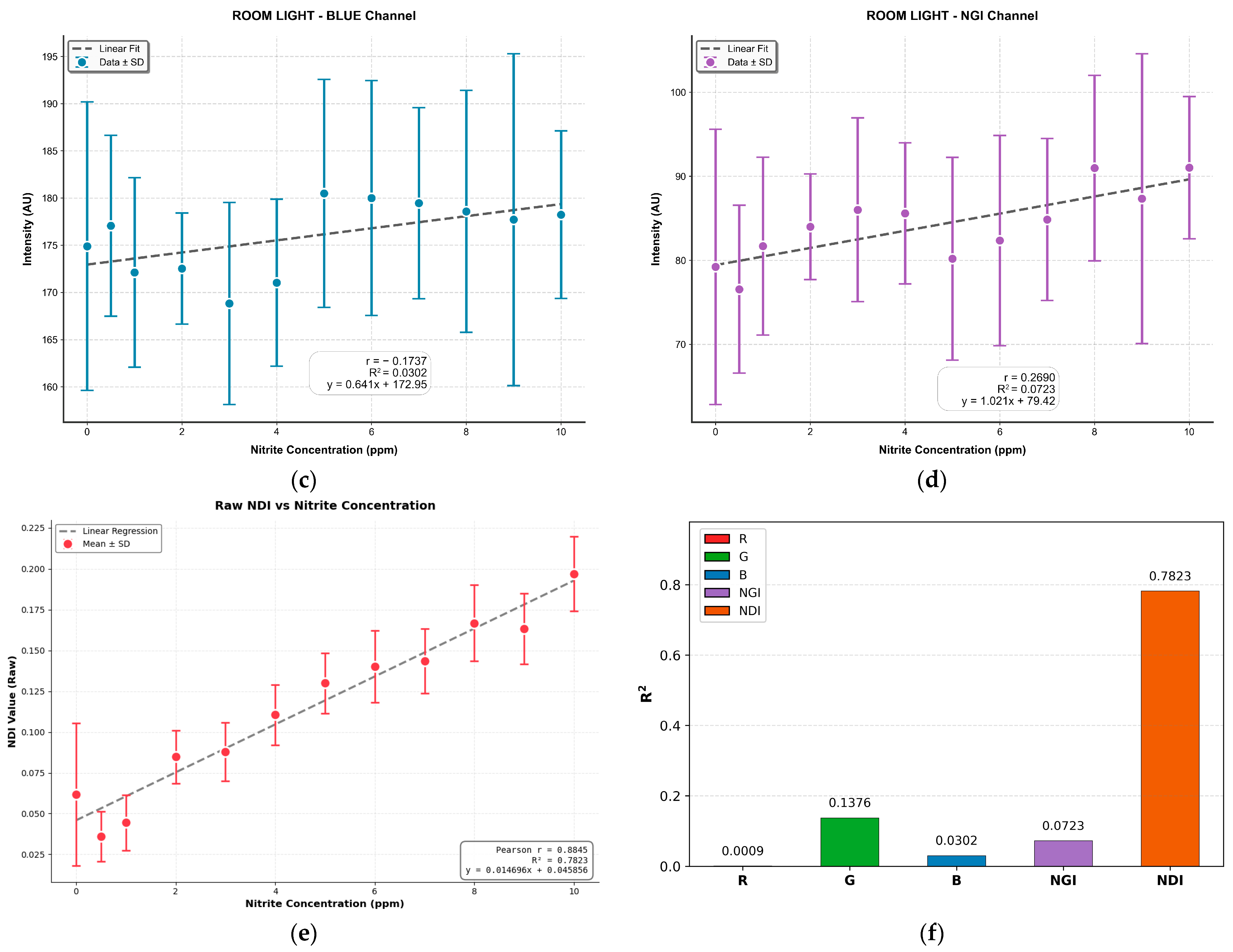

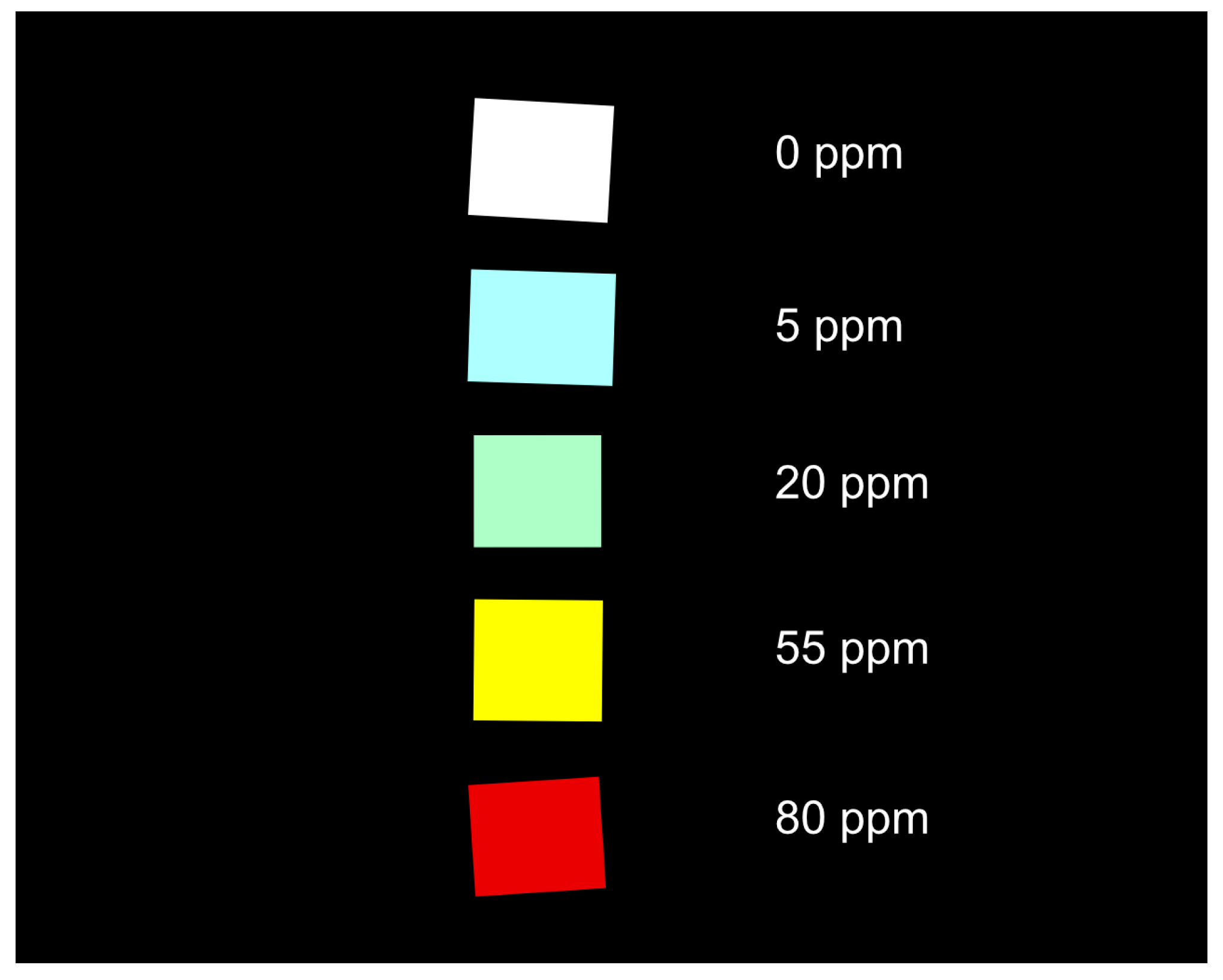

3.4. Comparison of MSI-Based NDI and Mobile Phone RGB Imaging for Sodium Nitrite Detection

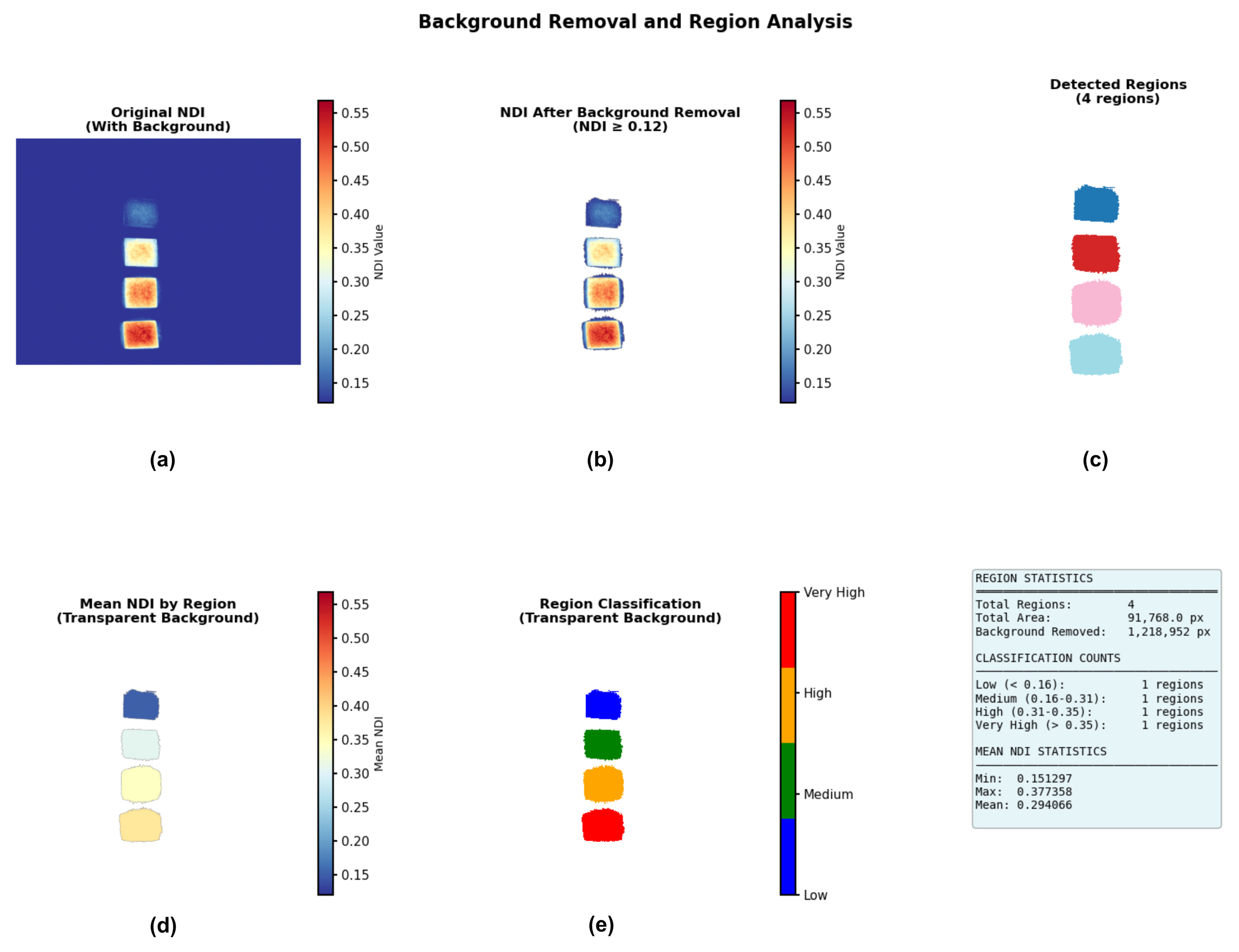

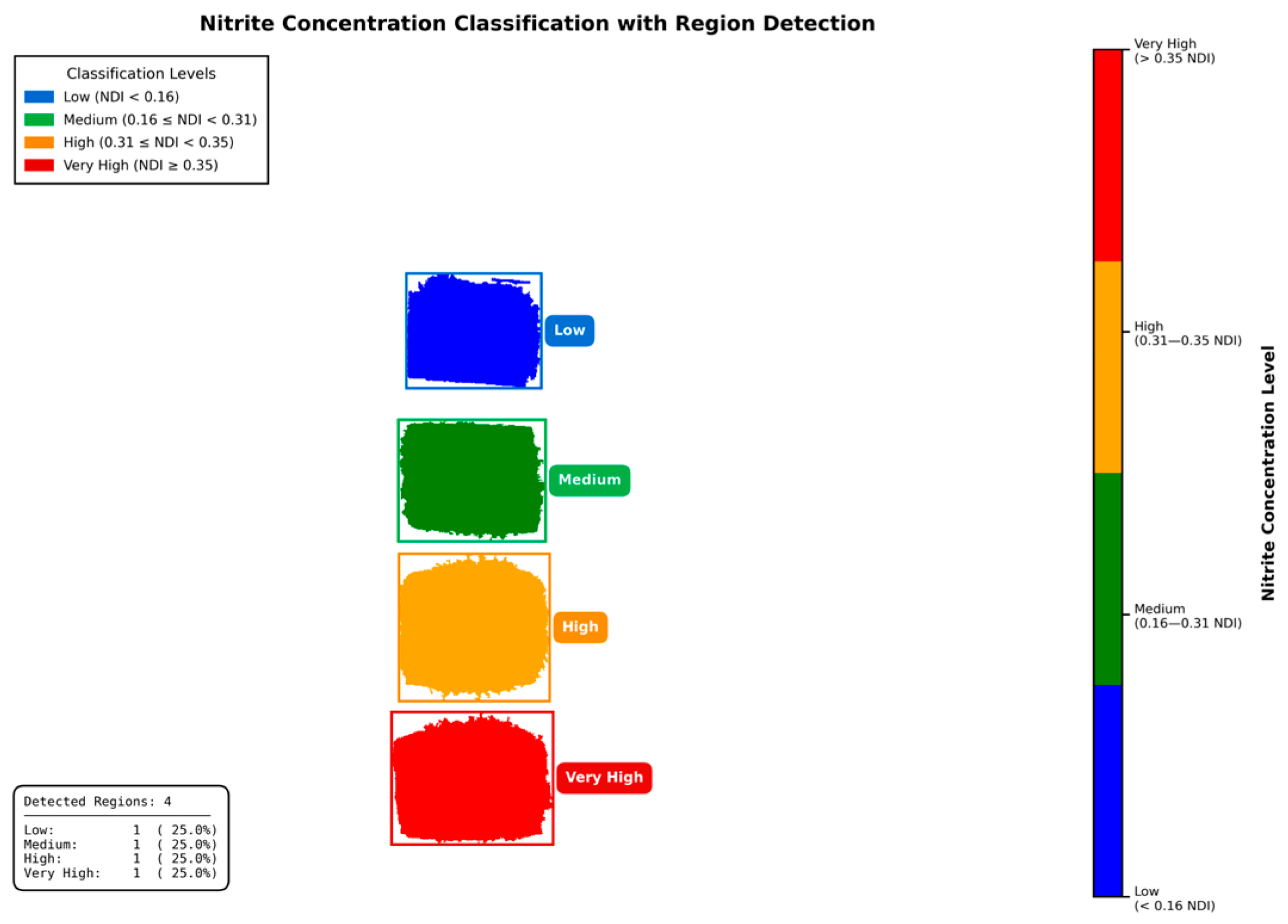

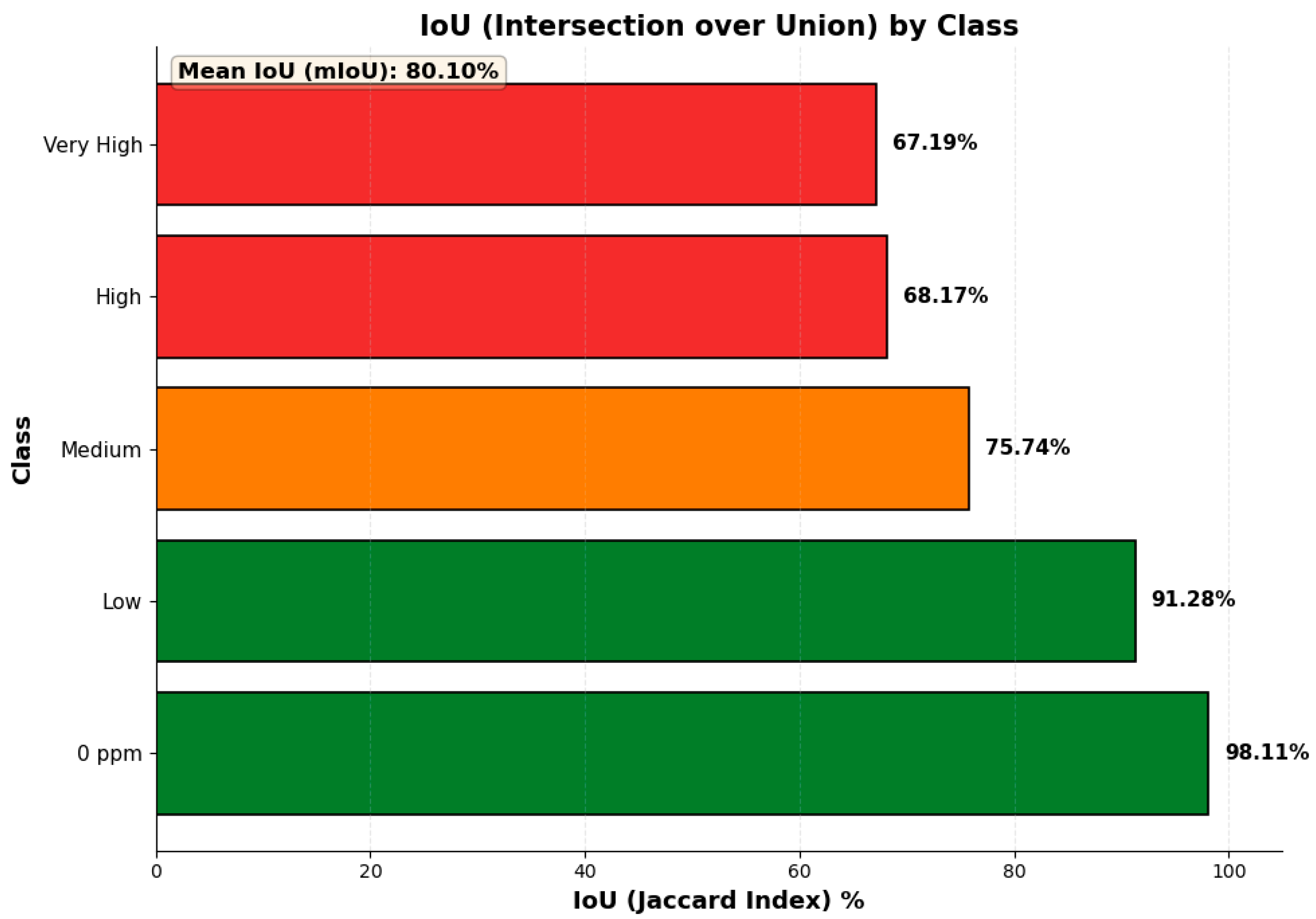

3.5. Segmentation and Classification

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamoudi, T.A.; Jalal, A.F.; Fakhre, N.A. Determination of nitrite in meat by azo dye formation. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Shakil, M.H.; Trisha, A.T.; Rahman, M.; Talukdar, S.; Kobun, R.; Huda, N.; Zzaman, W. Nitrites in Cured Meats, Health Risk Issues, Alternatives to Nitrites: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Blecker, C. LMOF serve as food preservative nanosensor for sensitive detection of nitrite in meat products. LWT 2022, 169, 114030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Campillo, C.; Hernández, J.D.D.; Guillén, I.; Campillo, N.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Torre-Minguela, C.D.; Viñas, P. Reddish Colour in Cooked Ham Is Developed by a Mixture of Protoporphyrins Including Zn-Protoporphyrin and Protoporphyrin IX. Foods 2022, 11, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.; Hunt, M.C.; Mancini, R.A.; Nair, M.N.; Denzer, M.L.; Suman, S.P.; Mafi, G.G. Recent Updates in Meat Color Research: Integrating Traditional and High-Throughput Approaches. Meat Muscle Biol. 2020, 4, 9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Saavedra, S.; Pietila, T.K.; Zapico, A.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Pajari, A.M.; González, S. Dietary Nitrosamines from Processed Meat Intake as Drivers of the Fecal Excretion of Nitrosocompounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 17588–17598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedsalehi, M.S.; Mohebbi, E.; Tourang, F.; Sasanfar, B.; Boffetta, P.; Zendehdel, K. Association of Dietary Nitrate, Nitrite, and N-Nitroso Compounds Intake and Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Toxics 2023, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Jia, G.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Z. Diet and Esophageal Cancer Risk: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare-Abidola, T.; Elabor, I.; Onwuchekwa, N.; Onwuchekwa, C.; Oladeji, J.; Olawale, A.O.; Adeiza, A.A. Environmental Impact Assessment of Abattoir Wastewater. Path Sci. 2025, 11, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, Y.; Zhou, B.; Xu, H. Nitrite: From Application to Detection and Development. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.H.; Jones, R.R.; Brender, J.D.; De Kok, T.M.; Weyer, P.J.; Nolan, B.T.; Villanueva, C.M.; Van Breda, S.G. Drinking water nitrate and human health: An updated review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Dusemund, B.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-evaluation of potassium nitrite (E 249) and sodium nitrite (E 250) as food additives. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04786. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaphal, P.; Dhamak, K. Review article on High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Method Development and Validation. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2022, 74, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, R.M.; Sharif, M.; Khan, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Abdullah, A.T.M. Simultaneous determination of nitrite and nitrate in meat and meat products using ion-exchange chromatography. Food Res. 2022, 6, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genualdi, S.; Jeong, N.; DeJager, L. Determination of endogenous concentrations of nitrites and nitrates in different types of cheese in the United States: Method development and validation using ion chromatography. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, I.; Lee, S.; Jung, M.J.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, P.S.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Son, K.H. Development and Application of Analytical Methods to Quantitate Nitrite in Excipients and Secondary Amines in Metformin API at Trace Levels Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Ahn, S.H.; Chang, Y.; Park, J.S.; Cho, H.; Kim, J.B. Development and Validation of a Sensitive LC-MS/MS Method for the Determination of N-Nitroso-Atenolol in Atenolol-Based Pharmaceuticals. Separations 2025, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Gc-ms analysis of biological nitrate and nitrite using pentafluorobenzyl bromide in aqueous acetone: A dual role of carbonate/bicarbonate as an enhancer and inhibitor of derivatization. Molecules 2021, 26, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Broderick, M.; Fein, H. Measurement of Nitric Oxide Production in Biological Systems by Using Griess Reaction Assay. Sensors 2003, 3, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Zhang, M.; Pan, Y.; Cai, J. Electrochemical Self-Assembled Gold Nanoparticle SERS Substrate Coupled with Diazotization for Sensitive Detection of Nitrite. Materials 2022, 15, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Xue, Z.; Abdu, H.I.; Shinger, M.I.; Idris, A.M.; Edris, M.M.; Shan, D.; Lu, X. Sensitive and selective colorimetric nitrite ion assay using silver nanoparticles easily synthesized and stabilized by AHNDMS and functionalized with PABA. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guembe-García, M.; González-Ceballos, L.; Arnaiz, A.; Fernández-Muiño, M.A.; Sancho, M.T.; Osés, S.M.; Ibeas, S.; Rovira, J.; Melero, B.; Represa, C.; et al. Easy Nitrite Analysis of Processed Meat with Colorimetric Polymer Sensors and a Smartphone App. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 37051–37058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongniramaikul, W.; Kleangklao, B.; Boonkanon, C.; Taweekarn, T.; Phatthanawiwat, K.; Sriprom, W.; Limsakul, W.; Towanlong, W.; Tipmanee, D.; Choodum, A. Portable Colorimetric Hydrogel Test Kits and On-Mobile Digital Image Colorimetry for On-Site Determination of Nutrients in Water. Molecules 2022, 27, 7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qu, H.; Yao, L.; Mao, Y.; Yan, L.; Dong, B.; Zheng, L. Hydrogel microsphere-based portable sensor for colorimetric detection of nitrite in food with matrix influence-eliminated effect. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 397, 134707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Bai, Q.; Hu, P.; Pan, J.; Liang, H.; Niu, X. Bifunctional manganese-doped silicon quantum dot-responsive smartphone-integrated paper sensor for visual multicolor/multifluorescence dual-mode detection of nitrite. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 392, 134143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogăcean, F.; Varodi, C.; Măgeruşan, L.; Pruneanu, S. Highly Sensitive Graphene-Based Electrochemical Sensor for Nitrite Assay in Waters. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Song, Y.Z.; Fang, F.; Wu, Z.Y. Sensitive paper-based analytical device for fast colorimetric detection of nitrite with smartphone. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 2665–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardane, B.M.; Wei, S.; McKelvie, I.D.; Kolev, S.D. Microfluidic paper-based analytical device for the determination of nitrite and nitrate. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 7274–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariati-Rad, M.; Irandoust, M.; Mohammadi, S. Multivariate analysis of digital images of a paper sensor by partial least squares for determination of nitrite. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016, 158, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbaji, A.; Heidari-Bafroui, H.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Faghri, M. A new paper-based microfluidic device for improved detection of nitrate in water. Sensors 2021, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnarathorn, N.; Dungchai, W. Paper-based Analytical Device (PAD) for the Determination of Borax, Salicylic Acid, Nitrite, and Nitrate by Colorimetric Methods. J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 75, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregucci, D.; Calabretta, M.M.; Nazir, F.; Arias, R.J.R.; Biondi, F.; Desiderio, R.; Michelini, E. An origami colorimetric paper-based sensor for sustainable on-site and instrument-free analysis of nitrite. Sens. Diagn. 2025, 4, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, V.; Alankus, G.; Horzum, N.; Mutlu, A.Y.; Bayram, A.; Solmaz, M.E. Single-Image-Referenced Colorimetric Water Quality Detection Using a Smartphone. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5531–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Dong, C.; Wang, Y.; Shuang, S. A smartphone-adaptable dual-signal readout chemosensor for rapid detection of nitrite in food samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 118, 105179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Han, D.; Su, B. A Comparison of UAV RGB and Multispectral Imaging in Phenotyping for Stay Green of Wheat Population. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, Z.; Morales-Ona, A.G.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, T.; Quinn, D.J.; Jin, J. A Portable High-Resolution Snapshot Multispectral Imaging Device Leveraging Spatial and Spectral Features for Non-Invasive Corn Nitrogen Treatment Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoorn, H.; Schraven, A.; van Dam, H.; Meijer, J.; Sillé, R.; Lock, A.; van den Berg, S. Performance Characterization of an Illumination-Based Low-Cost Multispectral Camera. Sensors 2024, 24, 5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airado-Rodríguez, D.; Høy, M.; Skaret, J.; Wold, J.P. From multispectral imaging of autofluorescence to chemical and sensory images of lipid oxidation in cod caviar paste. Talanta 2014, 122, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhaphan, P.; Unob, F. Thread-based platform for nitrite detection based on a modified Griess assay. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 327, 128938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choodum, A.; Tiengtum, J.; Taweekarn, T.; Wongniramaikul, W. Convenient environmentally friendly on-site quantitative analysis of nitrite and nitrate in seawater based on polymeric test kits and smartphone application. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 243, 118812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Fu, N.-N.; Zhang, H.-S. A fluorescence quenching method for the determination of nitrite with Rhodamine 110. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2003, 59, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantinantrakun, A.; Thompson, A.K.; Terdwongworakul, A.; Teerachaichayut, S. Assessment of Nitrite Content in Vienna Chicken Sausages Using Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging. Foods 2023, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, F.; Marconcini, M.; Ceccato, P. Normalized Difference Flood Index for rapid flood mapping: Taking advantage of EO big data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 712–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aini Rahmi, M.A.; Parikesit, P.; Withaningsih, S. Vegetation change analysis using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in Sumedang Regency. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 495, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanu, O.R.; Savitha, R.; Kapoor, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Karthik, V.; Pushpavanam, S. A Facile Colorimetric Sensor for Sensitive Detection of Nitrite in the Simulated Saliva. Sens. Imaging 2024, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The pascal visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bandpass Filters | CWL | FWHM | Model/Part No. | Manufacturers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV | 360 nm | ~40 nm | BP360 | HuaTeng Vision, Shenzhen, China |

| Blue | 475 nm | ~18 nm | BP475 | Nano Macro Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China |

| Green | 550 nm | ~22 nm | BP550 | Nano Macro Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China |

| Red | 670 nm | ~26 nm | BP670 | Nano Macro Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China |

| Red Edge | 710 nm | ~12 nm | BP710 | Nano Macro Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China |

| NIR | 800 nm | ~30 nm | BP800 | Nano Macro Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China |

| NIR | 808 nm | ~40 nm | BP808 | HuaTeng Vision, Shenzhen, China |

| NIR | 850 nm | ~40 nm | FS03-BP850 | HuaTeng Vision, Shenzhen, China |

| NIR | 940 nm | ~40 nm | FS03-BP940 | HuaTeng Vision, Shenzhen, China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kataphiniharn, C.; Unsuree, N.; Janchaysang, S.; Lumjeak, S.; Tulyananda, T.; Wangkham, T.; Srichola, P.; Nithiwutratthasakul, T.; Chattham, N.; Phanphak, S. Portable Multispectral Imaging System for Sodium Nitrite Detection via Griess Reaction on Cellulose Fiber Sample Pads. Sensors 2025, 25, 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237323

Kataphiniharn C, Unsuree N, Janchaysang S, Lumjeak S, Tulyananda T, Wangkham T, Srichola P, Nithiwutratthasakul T, Chattham N, Phanphak S. Portable Multispectral Imaging System for Sodium Nitrite Detection via Griess Reaction on Cellulose Fiber Sample Pads. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237323

Chicago/Turabian StyleKataphiniharn, Chanwit, Nawapong Unsuree, Suwatwong Janchaysang, Sumrerng Lumjeak, Tatpong Tulyananda, Thidarat Wangkham, Preeyanuch Srichola, Thanawat Nithiwutratthasakul, Nattaporn Chattham, and Sorasak Phanphak. 2025. "Portable Multispectral Imaging System for Sodium Nitrite Detection via Griess Reaction on Cellulose Fiber Sample Pads" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237323

APA StyleKataphiniharn, C., Unsuree, N., Janchaysang, S., Lumjeak, S., Tulyananda, T., Wangkham, T., Srichola, P., Nithiwutratthasakul, T., Chattham, N., & Phanphak, S. (2025). Portable Multispectral Imaging System for Sodium Nitrite Detection via Griess Reaction on Cellulose Fiber Sample Pads. Sensors, 25(23), 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237323