Measurement of Mass Flow Rates of Petrochemical Particles Based on an Electrostatic Coupled Capacitance Sensor

Abstract

1. Introduction

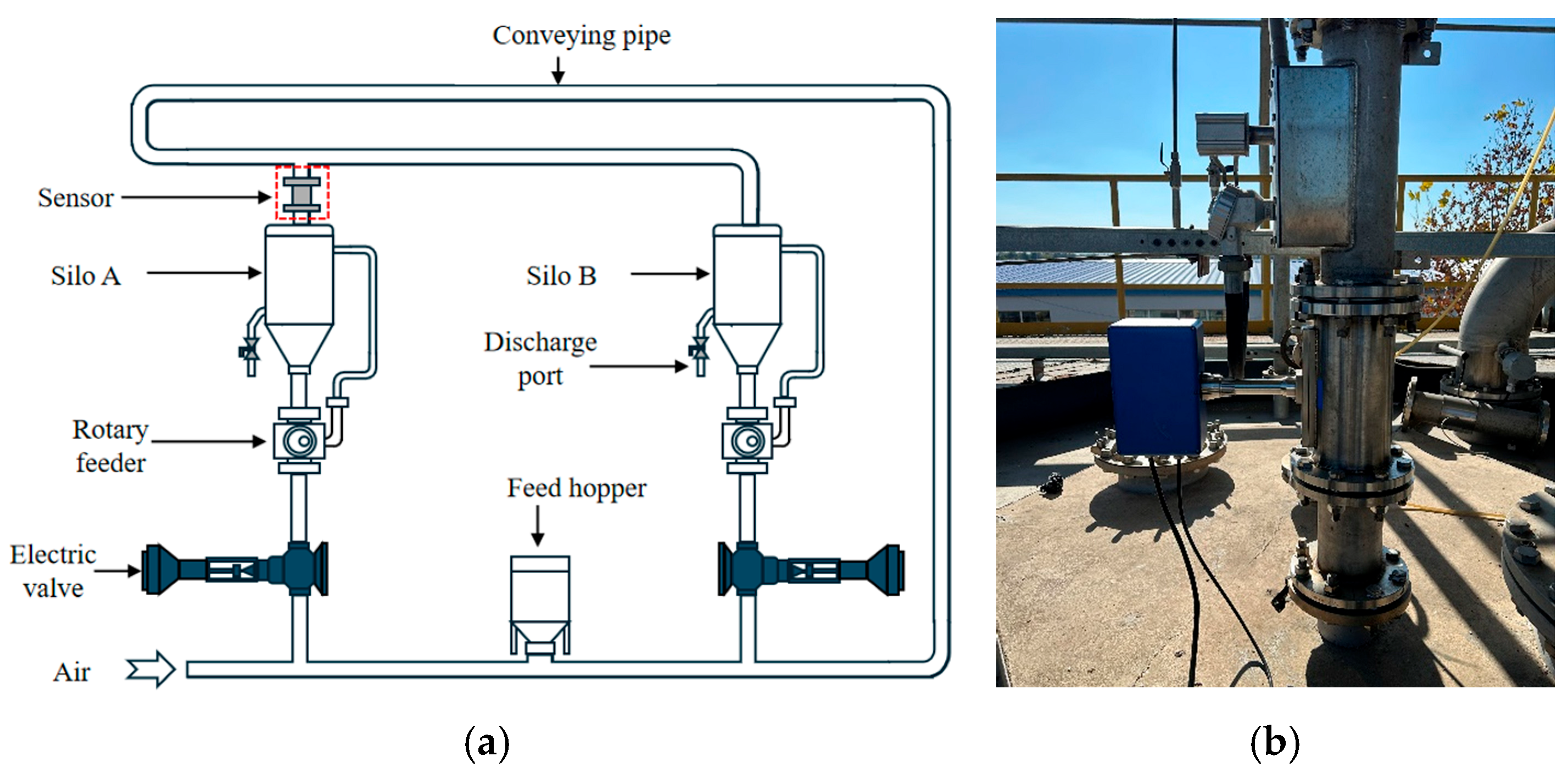

2. Measurement System Development

2.1. Measurement System Design

2.2. Particle Parameter Calculation

3. Experimental Setups

3.1. The Belt–Pulley Setup

3.2. The Laboratory-Scale Pneumatic Conveying Rig

3.3. The Pilot-Scale Pneumatic Conveying Rig

4. Results and Discussion

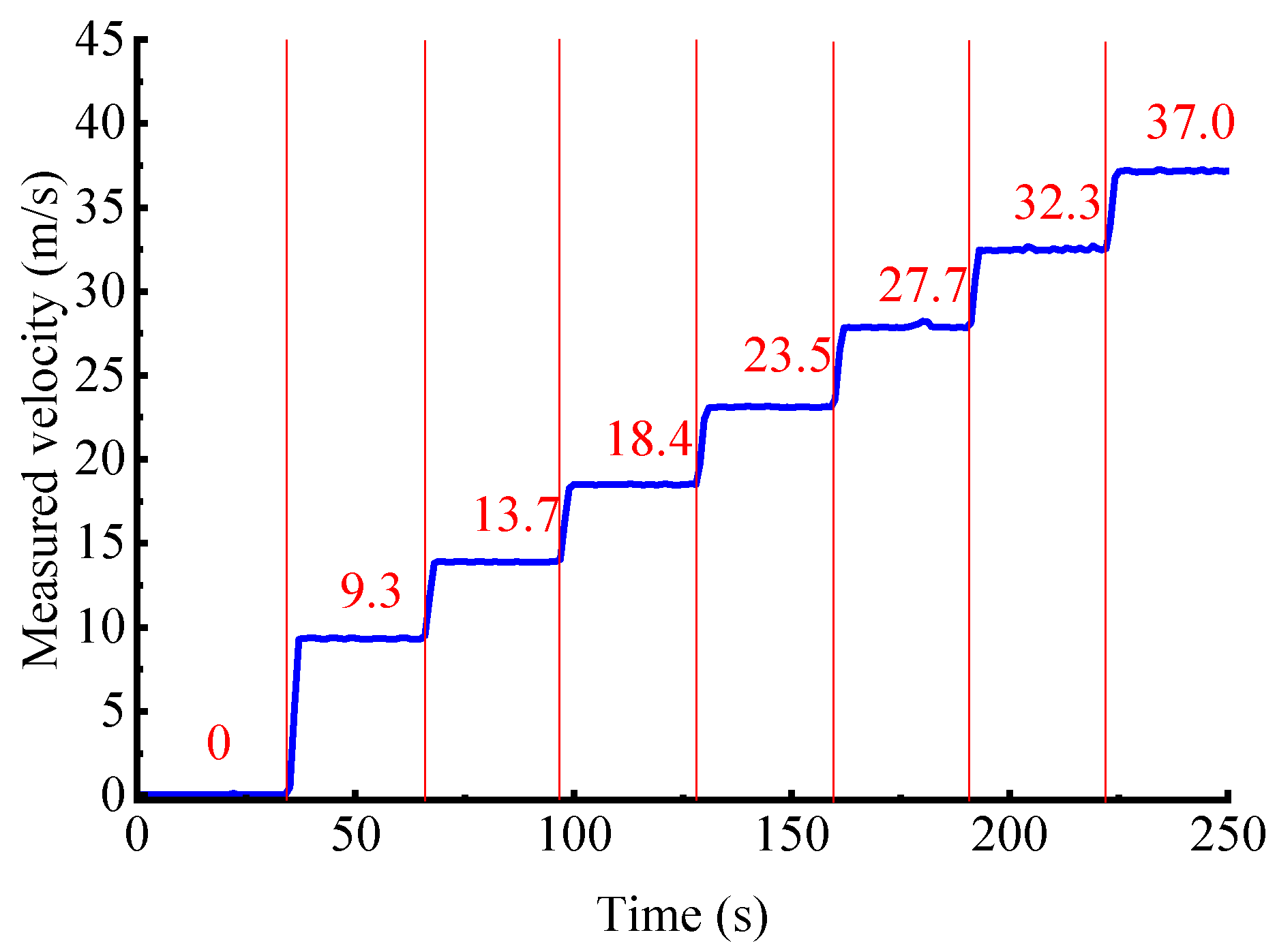

4.1. Measurement Results from the Belt–Pulley Setup

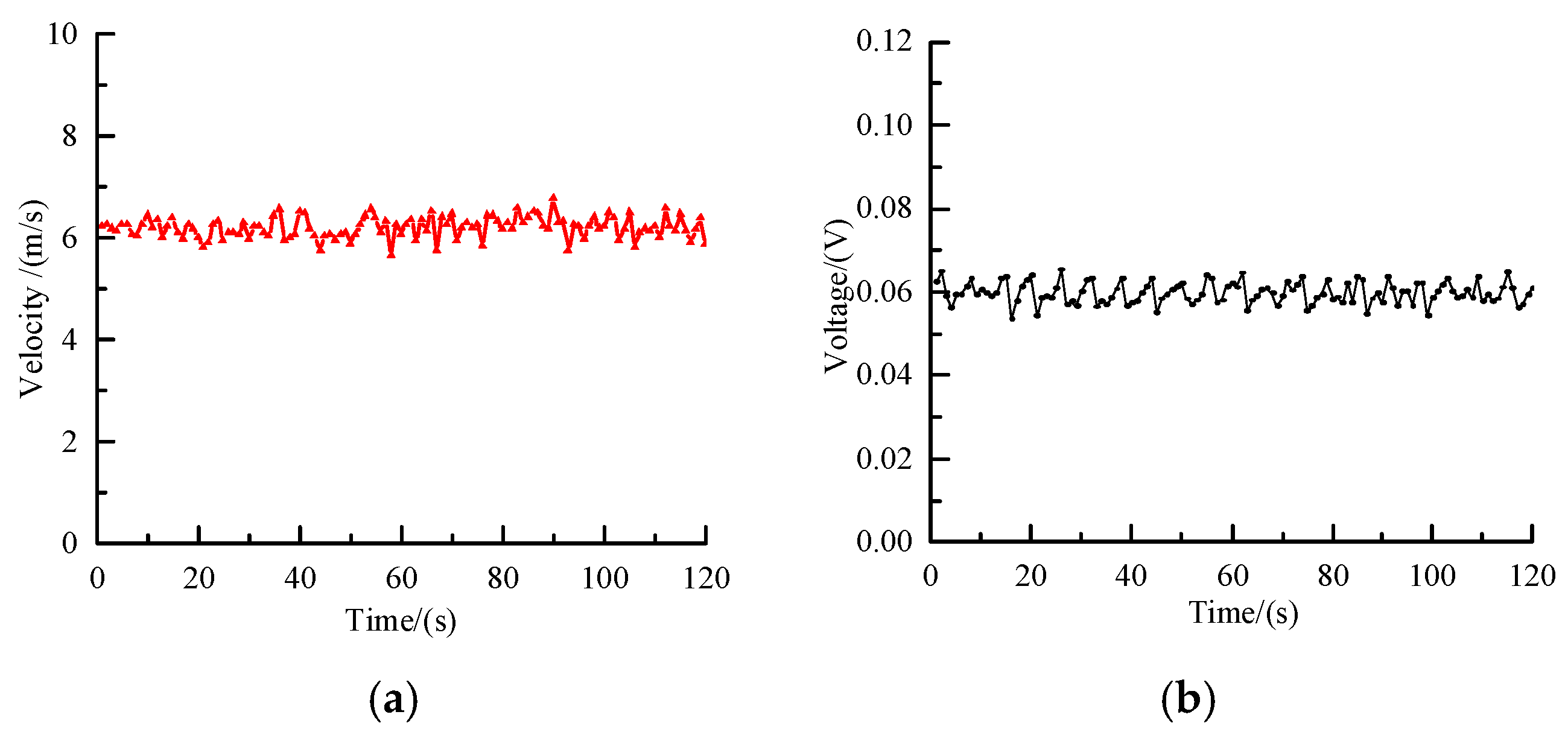

4.2. Measurement Results from the Lab-Scale Pneumatic Conveying Rig

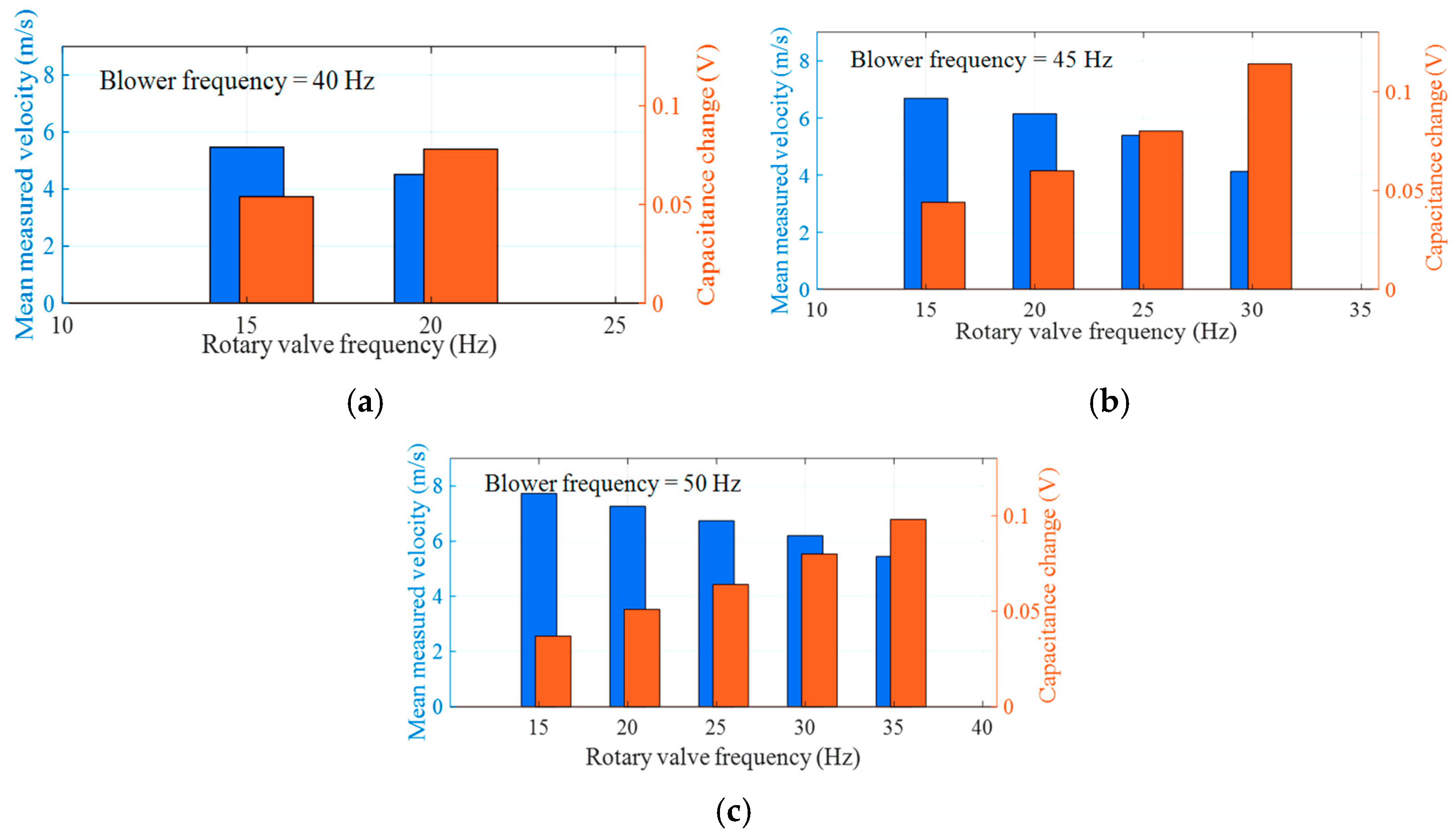

4.3. Measurement Results from the Pilot-Scale Pneumatic Conveying Rig

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossain, M.T.; Shahid, M.A.; Mahmud, N.; Habib, A.; Rana, M.M.; Khan, S.A.; Hossain, M.D. Research and application of polypropylene: A review. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaki, A.; Hammoud, A.; Masad, E.; Khraisheh, M.; Abdala, A.; Ouederni, M. A review on material extrusion (MEX) of polyethylene—Challenges, opportunities, and future prospects. Polymer 2024, 307, 127333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.P.; Huang, Z.X.; Yang, Z.T.; Zhang, G.Z.; Yin, X.C.; Feng, Y.H.; He, H.Z.; Jin, G.; Wu, T.; He, G.J.; et al. Industrial-scale polypropylene–polyethylene physical alloying toward recycling. Engineering 2022, 9, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.M.; Deng, H.W.; Liu, J. Particle velocity measurement using linear capacitive sensor matrix. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th IEEE International Conference on Electronic Measurement & Instruments (ICEMI), Yangzhou, China, 20–22 October 2017; pp. 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Arakaki, C.; Ghaderi, A.; Datta, B.K.; Lie, B. Non-intrusive mass flow measurements in pneumatic transport. In Proceedings of the CHoPS-05, 5th International Conference for Conveying and Handling of Particulate Solids, Sorrento, Italy, 27–30 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F.F. Research progress on gas-solid two-phase flow parameter detection technologies. J. Univ. Jinan (Sci. Technol.) 2017, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, A.L.; Bakalis, S.; Watson, N.J. A review of in-line and on-line measurement techniques to monitor industrial mixing processes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 153, 463–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Van Ommen, J.R.; Liu, D.; Mudde, R.F.; Chen, X.; Wagner, E.C.; Liang, C. Fluidization dynamics of cohesive Geldart B particles. Part I: X-ray tomography analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Q. Review of techniques for the mass flow rate measurement of pneumatically conveyed solids. Measurement 2011, 44, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jia, L.; Gao, W.B. Electrostatic sensor for determining the characteristics of particles moving from deposition to suspension in pneumatic conveying. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 20, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Byrne, B.; Woodhead, S.; Coulthard, J. Velocity measurement of pneumatically conveyed solids using electrodynamic sensors. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.L.; Li, J.; Wang, S.M. A spatial filtering velocimeter for solid particle velocity measurement based on linear electrostatic sensor array. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2012, 26, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Yan, J.; Yan, Y. Measurement of the moisture content in woodchips through capacitive sensing and data-driven modelling. Measurement 2021, 186, 110205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bi, D.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, C.L. Online monitoring and characterization of dense phase pneumatically conveyed coal particles on a pilot gasifier by electrostatic-capacitance-integrated instrumentation system. Measurement 2018, 125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Frias, M.A.R.; Mokhtar, K.Z.; Yang, W. An integrated ECT and electrostatic sensor for particulate flow measurement. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST), Kraków, Poland, 16–18 October 2018; pp. 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.H. Investigation on hydrodynamics of triple-bed combined circulating fluidized bed using electrostatic sensor and electrical capacitance tomography. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 11198–11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, S.P.; Tang, Z.; Wang, H.R.; Zhang, B.; Xu, C.L. Electrostatic coupled capacitance sensor for gas-solid flow measurement. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 12807–12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, C.L. Development of ring-shaped electrostatic coupled capacitance sensor for the parameter measurement of gas-solid flow. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2021, 43, 2567–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | rm/r/min | vr/m/s | vc/m/s | Relative Error/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 590 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 1.08 |

| 2 | 891 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 1.23 |

| 3 | 1 192 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 0.54 |

| 4 | 1 493 | 23.4 | 23.5 | 0.42 |

| 5 | 1 794 | 28.2 | 27.7 | 1.77 |

| 6 | 2 096 | 32.9 | 32.3 | 1.82 |

| 7 | 2 368 | 37.2 | 37.0 | 0.54 |

| Rotary Valve Frequency/Hz | Mass Flow Rate/g/s |

|---|---|

| 10 | 21.81 |

| 15 | 32.67 |

| 20 | 42.62 |

| 25 | 52.91 |

| 30 | 63.03 |

| 35 | 72.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Meng, H.; Wang, G.; Li, J. Measurement of Mass Flow Rates of Petrochemical Particles Based on an Electrostatic Coupled Capacitance Sensor. Sensors 2025, 25, 6850. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226850

Li Y, Meng H, Wang G, Li J. Measurement of Mass Flow Rates of Petrochemical Particles Based on an Electrostatic Coupled Capacitance Sensor. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6850. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226850

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yipeng, He Meng, Guangzu Wang, and Jian Li. 2025. "Measurement of Mass Flow Rates of Petrochemical Particles Based on an Electrostatic Coupled Capacitance Sensor" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6850. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226850

APA StyleLi, Y., Meng, H., Wang, G., & Li, J. (2025). Measurement of Mass Flow Rates of Petrochemical Particles Based on an Electrostatic Coupled Capacitance Sensor. Sensors, 25(22), 6850. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226850