1. Introduction

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) is a high-resolution active sensing technology capable of operating under all-weather, day-and-night conditions. By exploiting microwave backscatter rather than ambient light, SAR is inherently robust to atmospheric interference such as clouds, fog, and precipitation, making it highly effective for maritime surveillance and target detection in complex environments. Nevertheless, cluttered backgrounds, geometric distortions, and the sparse distribution of ship targets in SAR imagery pose significant challenges for conventional object detection frameworks, often resulting in reduced accuracy and limited generalization. These constraints underscore the need for lightweight, context-aware detection models that are specifically tailored to the unique spatial and statistical properties of SAR data. Effective frameworks must balance real-time efficiency for deployment in resource-constrained environments with robustness to small-scale or partially occluded targets and ambiguous backscatter signatures. Addressing these challenges is essential to enable accurate, persistent, and automated monitoring across maritime, environmental, and defense-related applications [

1,

2,

3].

Traditional ship detection methods, such as the Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) algorithm [

3], have been widely employed due to their adaptive thresholding capability in clutter-rich maritime environments. While CFAR is effective in controlled or relatively simple scenarios, its performance often degrades in practical SAR applications. The algorithm relies on manually defined features and expert-set parameters, which increase processing time and limit scalability. In complex maritime conditions—characterized by varying sea states, heterogeneous backgrounds, and low signal-to-clutter ratios—CFAR frequently suffers from reduced accuracy and weak generalization [

4]. This limitation stems from its dependence on accurate clutter modeling and continuous threshold calibration, both of which must dynamically adapt to changing environments to reduce false alarms and missed detections. With the growing complexity of SAR data and the increasing demand for real-time, high-precision maritime surveillance, traditional approaches such as CFAR alone are insufficient [

5]. To address these issues, several enhanced CFAR variants and hybrid detection frameworks have been proposed, as briefly discussed in [

2,

6].

Recent advances in deep learning have greatly advanced SAR ship detection, with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

7,

8] demonstrating strong ability to learn hierarchical representations directly from raw data. Two main categories of CNN-based object detection architectures are commonly employed. The first, known as two-stage detectors, follows a coarse-to-fine strategy: region proposals are generated initially, followed by classification and bounding-box regression in a second stage. Representative models include Faster R-CNN [

9], Libra R-CNN [

10], and Mask R-CNN [

11]. These methods typically achieve high detection accuracy but incur significant computational cost, which limits their suitability for real-time applications. The second category, single-stage detectors, performs classification and localization jointly in a unified pipeline. Examples include the YOLO family [

12], SSD [

13], and FCOS [

14]. Owing to their end-to-end training design, single-stage detectors generally offer superior speed and simplicity, albeit sometimes at the expense of slightly reduced accuracy compared with two-stage approaches.

In SAR ship detection, key challenges stem from scale variation, occlusion, and directional backscattering, which complicate feature extraction. Background clutter, including speckle noise and sea surface texture, often leads to false alarms, particularly in lightweight models. Although deeper CNNs theoretically provide larger receptive fields, only a limited central region [

15] significantly influences prediction. The fixed and spatially rigid receptive fields of CNNs make it difficult to adapt to ships of varying scales and orientations, a problem further amplified in coastal, port, and inland scenes where object–background confusion is common. These limitations highlight the need for tunable, multi-scale, and context-aware detection mechanisms.

To address these issues, recent works have explored diverse strategies. Zhao et al. [

16] proposed the Attention Receptive Pyramid Network (ARPN), integrating Receptive Fields Block (RFB) and CBAM [

17] to enhance global–local dependencies and suppress clutter. Tang et al. [

18] introduced deformable convolutions with BiFormer attention and Wise-IOU loss to improve adaptability in complex SAR scenes. Zhou et al. [

19] developed MSSDNet, a lightweight YOLOv5s-based model with CSPMRes2 and an FC-FPN module for adaptive multi-scale fusion. Cui et al. [

20] enhanced CenterNet with shuffle-group attention to strengthen semantic extraction and reduce coastal false alarms. More recently, Sun et al. [

21] proposed BiFA-YOLO, which employs a bidirectional feature-aligned module for improved detection of rotated and small ships. Overall, these studies emphasize that effective SAR ship detection requires models capable of balancing local detail sensitivity with global contextual awareness, particularly in cluttered and multi-scale maritime environments.

SAR ship datasets contain a high proportion of small targets with limited appearance cues such as texture and contour, making them challenging to detect. Detection performance is often hindered by the scarcity of features extracted from small ships and the mismatch between their scale and the large receptive fields or anchor sizes of conventional detectors. As mainstream frameworks typically downsample images to obtain semantic-rich features, critical information for small targets may be lost, leading to frequent missed detections [

3,

4,

22].

To address these issues, several lightweight attention-augmented approaches have been proposed. Hu et al. [

23] introduced BANet, an anchor-free detector with balanced attention modules that enhance multi-scale and contextual feature learning. Zhou et al. [

24] proposed a multi-attention model for large-scene SAR images, enhancing detection performance in complex background environments. Guo et al. [

25] further extended CenterNet with multi-level refinement and fusion modules to strengthen small-ship detection and suppress clutter with minimal overhead.

Despite progress with compact detectors that cut redundancy and incorporate attention for scale adaptability, reliable SAR ship detection remains difficult. Lightweight models, in particular, struggle with clutter, noise, and scale variation due to limited context modeling and rigid receptive fields. These gaps motivate the design of specialized, domain-tailored frameworks. To address these limitations, this paper proposes DRC2-Net, a compact and context-aware enhancement of YOLOX-Tiny. The proposed framework integrates lightweight semantic reasoning and adaptive spatial modules to strengthen feature representation, improve geometric adaptability, and enhance detection robustness in complex maritime scenes, all while maintaining high efficiency.

Although recent lightweight SAR detectors have achieved progress in reducing model complexity and incorporating attention mechanisms, they still struggle to capture global context and adapt to geometric variations in complex maritime clutter. Conventional convolutional structures, limited by fixed receptive fields, often fail to model long-range dependencies, leading to false alarms or missed detections—especially for small or irregular ship targets. These limitations motivate the need for a compact yet adaptive architecture specifically designed for SAR ship detection. To this end, -Net integrates RCCA and DCNv2 in a domain-specific manner, with DCNv2 selectively inserted at three critical neck locations identified through ablation studies. This design enhances geometric adaptability and contextual reasoning while maintaining a lightweight 5.05 M-parameter structure optimized for real-time maritime applications. The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Enhanced Semantic Context Modeling: Long-range spatial dependencies are captured by integrating a recurrent attention mechanism after the SPPBottleneck in the backbone. This placement enables semantic reasoning over fragmented, elongated, or partially visible ship structures, improving robustness against weak or ambiguous contours in complex maritime scenes.

Adaptive and Flexible Receptive Fields: A novel DeCSP module embeds deformable convolutions into the bottleneck paths of three CSP layers in the neck, enabling dynamic, content-aware sampling. This design adapts to irregular ship scales and shapes while recovering shallow and boundary information often overlooked by conventional FPN-based fusion.

Lightweight and Generalizable Detection Framework: The proposed DRC2-Net extends YOLOX-Tiny with targeted architectural enhancements while maintaining its lightweight nature (∼5.05M parameters). Evaluations on SSDD and iVision-MRSSD demonstrate strong generalization across varying resolutions, target densities, and clutter conditions, ensuring real-time performance suitable for maritime surveillance and edge deployment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the YOLOX-Tiny baseline and reviews the theoretical foundations of recurrent attention and deformable convolution.

Section 3 presents the proposed DRC

2-Net architecture, emphasizing its attention-aware and geometry-adaptive modules.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, datasets, evaluation metrics, and ablation studies conducted on SSDD and iVision-MRSSD. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main findings and discusses potential avenues for future research.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Network Structure of DRC2-Net

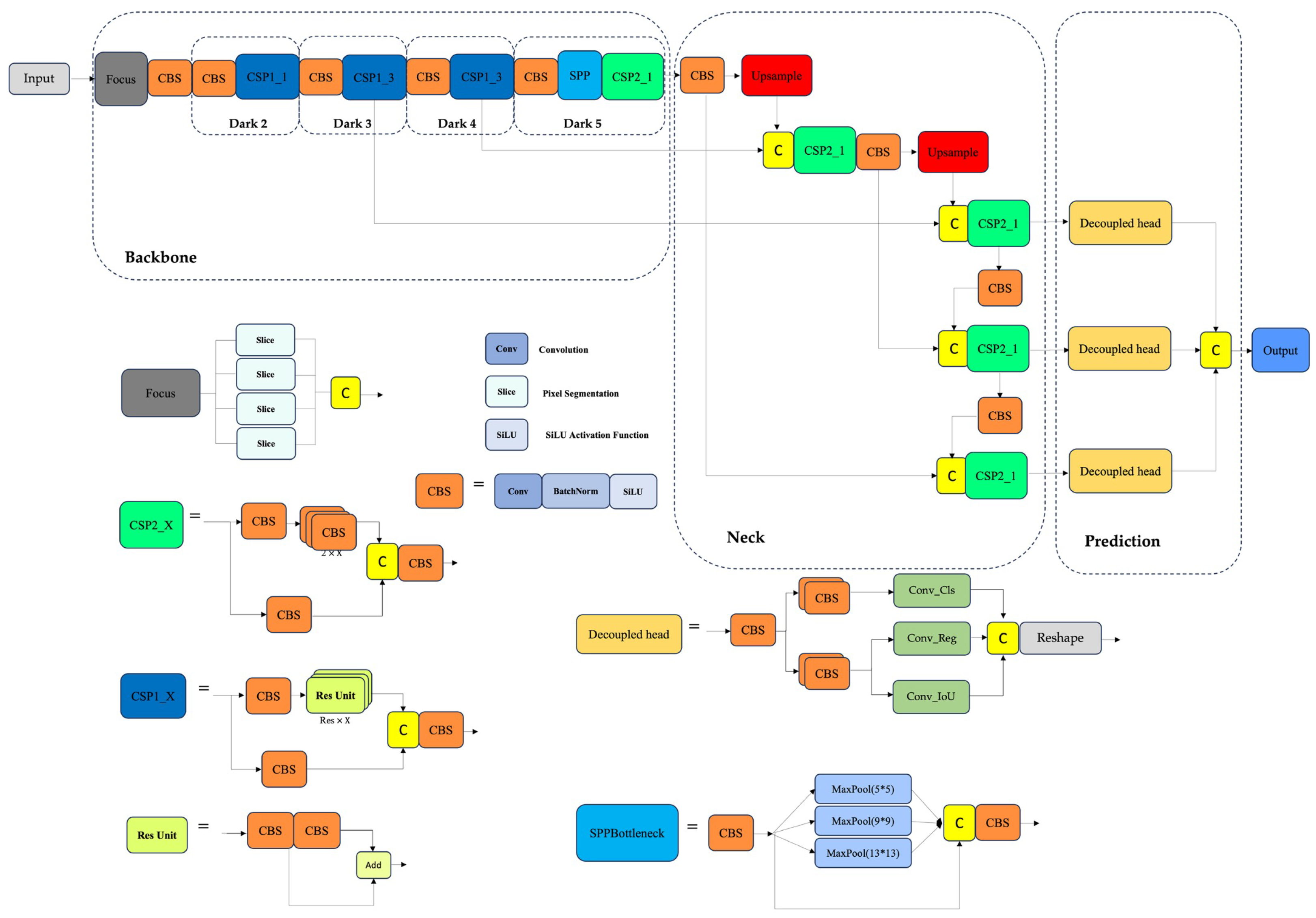

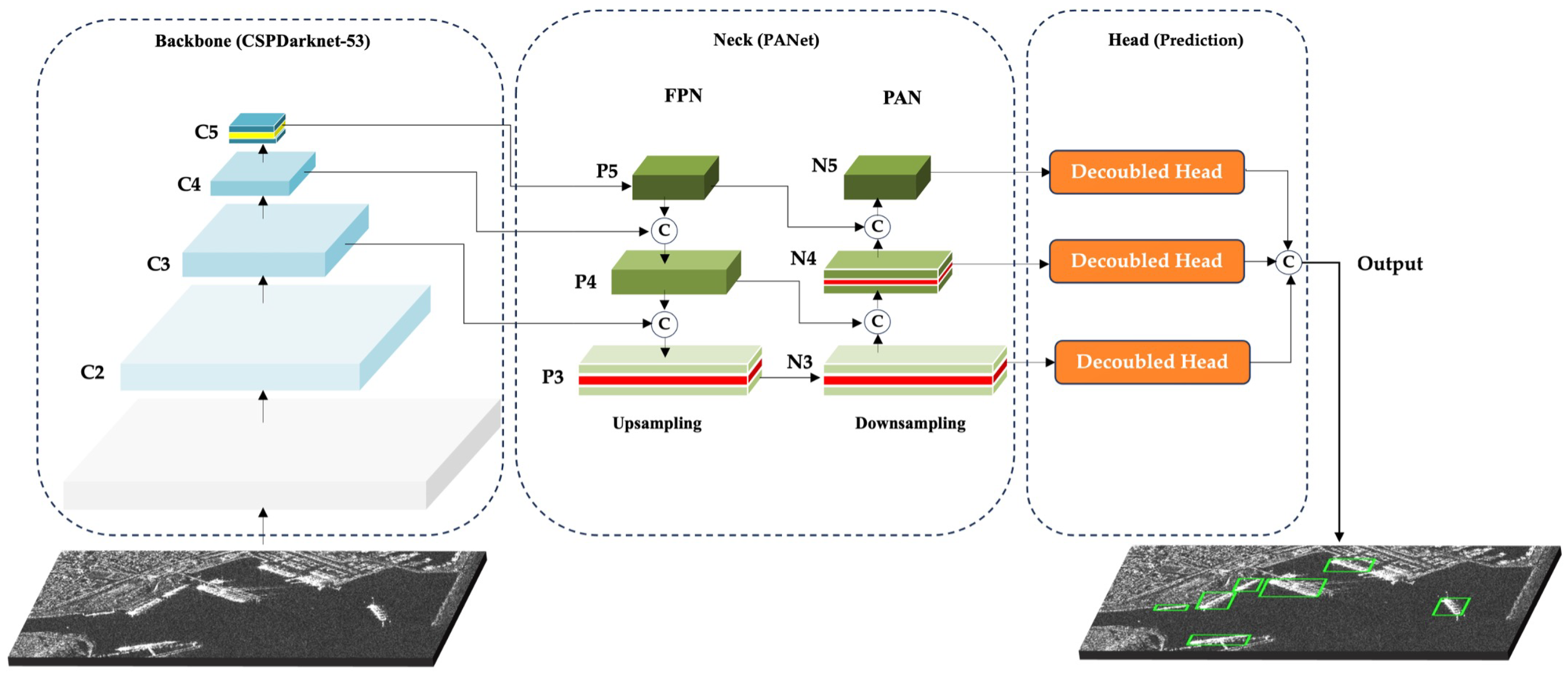

-Net is a lightweight, context-aware detector built on the YOLOX-Tiny framework, noted for its balance of speed, compactness, and accuracy in real-time applications. While YOLOX-Tiny serves as a solid baseline, it encounters limitations in SAR imagery, especially when detecting sparse or partially visible ships within challenging maritime environments characterized by speckle noise and background artifacts. To address these challenges, this work introduces dual-modular enhancements applied to both the backbone and neck. The backbone preserves the four-stage design (Dark2–Dark5), producing feature maps C2–C5, with C3–C5 used as P3–P5 for detection, forming a hierarchical progression from high-resolution to high-semantic features. To strengthen deep semantic reasoning, the RCCA module is placed after the SPP bottleneck in Dark5, capturing horizontal and vertical dependencies through iterative refinement. This improves discrimination of ship targets while preserving the network’s lightweight efficiency.

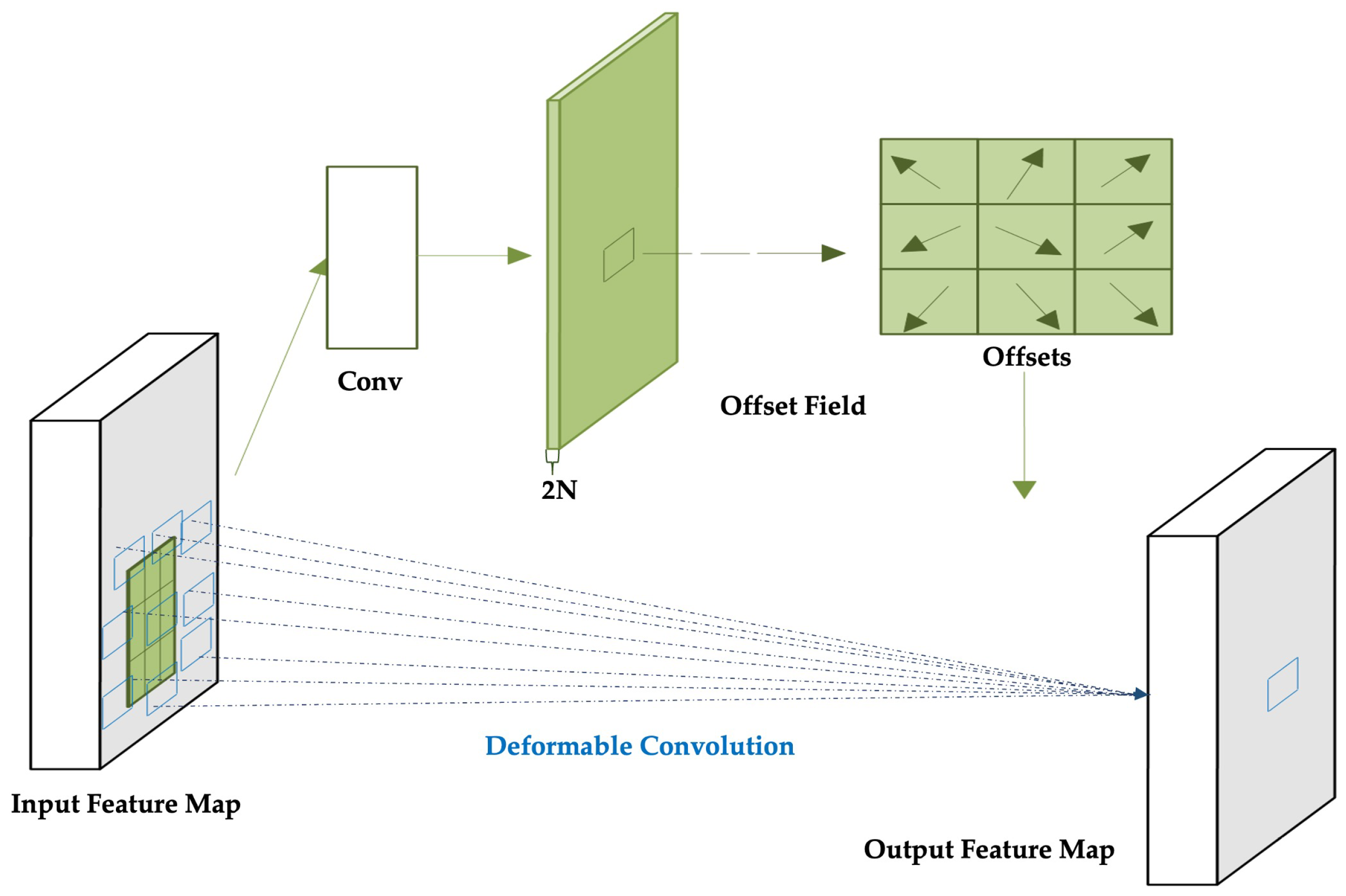

In the neck, a bidirectional feature fusion strategy is adopted to enhance multi-scale ship representation. The top-down path first propagates deep semantic features to generate the feature pyramids P3, P4, and P5, which capture coarse but highly informative contextual cues. To preserve the fine-grained spatial details essential for detecting small or partially occluded ships, a bottom-up enhancement path subsequently aggregates shallow features upward, producing the refined outputs N3, N4, and N5. To further improve geometric adaptability within this fusion process, DCNv2 are strategically embedded into key CSP blocks. Unlike standard convolution, DCNv2 introduces modulated learnable offsets. This mechanism predicts not only spatial adjustments to the sampling grid but also a modulation mask that weights the contribution of each sampled value. Consequently, the network dynamically adjusts its receptive field in both position and intensity based on the local geometry of the input features, leading to superior adaptation to the diverse and complex shapes of maritime targets.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the input SAR image is first processed by the backbone (Dark2–Dark5), which extracts hierarchical features represented as C2–C5. From these, multi-scale pyramids P3–P5 are constructed, capturing small, medium, and large-target information. These pyramids are then fed into the neck, where bidirectional fusion generates intermediate maps N3–N5, enriching feature interactions across scales. Finally, three decoupled detection heads operate on N3–N5 to predict classification scores and bounding-box (BBox) regression. This end-to-end pipeline—from backbone encoding, through pyramid feature generation, to neck fusion and multi-head prediction—illustrates how the proposed framework transforms raw SAR imagery into accurate and scale-aware ship detections. Strategic enhancements within the backbone and neck further strengthen semantic continuity and geometric adaptability while maintaining the lightweight nature of the design.

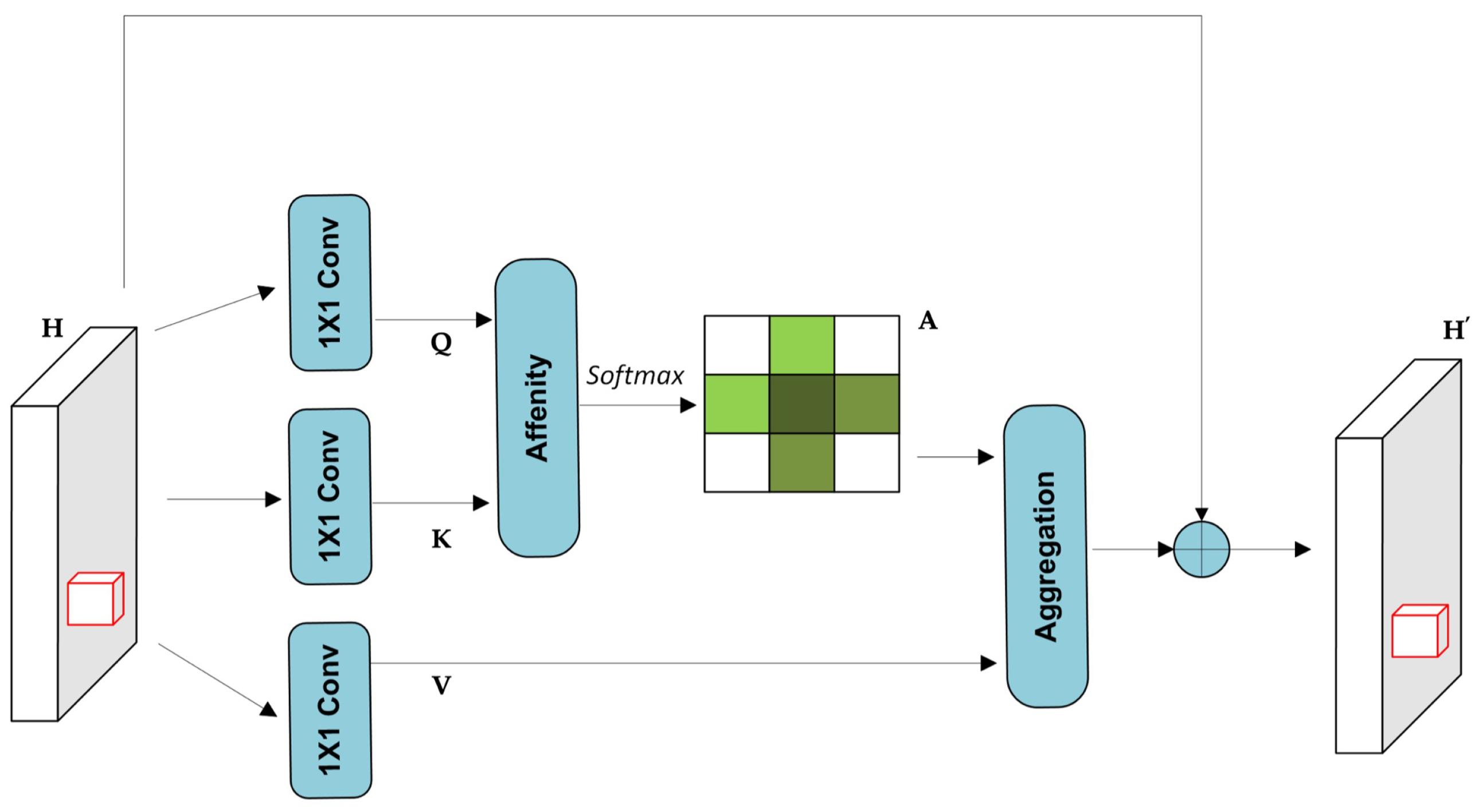

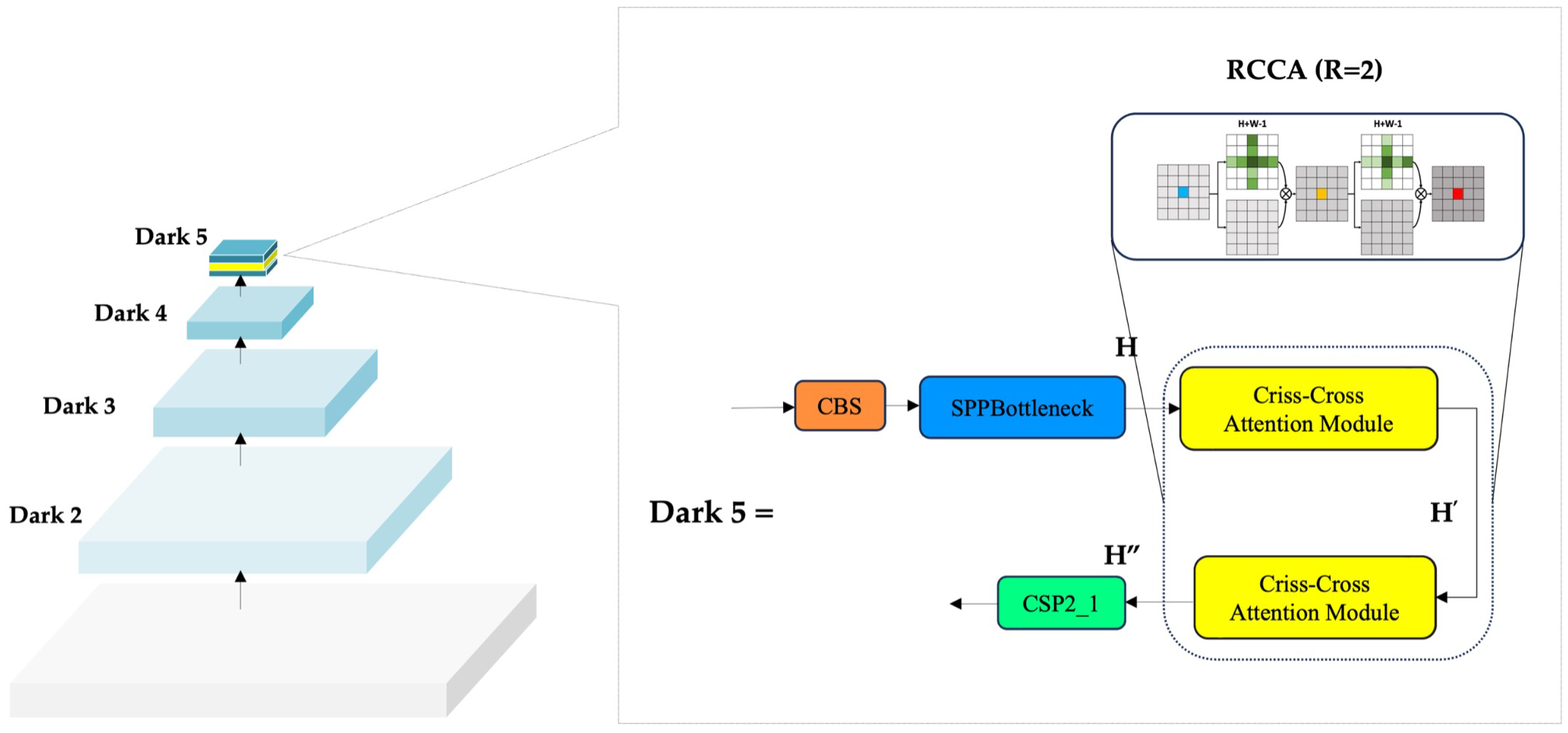

3.2. RCCA Integration for Sparse Maritime Contextual Enhancement

In CNNs, spatial resolution diminishes with depth, reducing the ERF and causing loss of fine-grained detail. This is especially problematic for hard-to-detect samples such as small or partially visible ships, where complex backscatter and multi-path reflections obscure object boundaries and increase false negatives. To mitigate this,

-Net integrates the RCCA module at the deepest backbone stage. As shown in

Figure 7, RCCA is placed immediately after the SPPBottleneck block in Dark5, where semantic abstraction is high but spatial precision is weakened. By iteratively aggregating horizontal and vertical context, RCCA expands the ERF and restores continuity across distant regions while preserving essential spatial cues. This placement enables the network to better distinguish fragmented or low-contrast ships from background clutter with minimal overhead.

RCCA enhances semantic continuity through a lightweight two-pass refinement (), following the setting validated in the official CCNet paper. Compared with single-pass CCA (), the second recurrence enables dense contextual aggregation across all spatial locations without adding parameters or incurring significant computational cost. This extended context is particularly beneficial in SAR ship detection, where elongated or low-contrast vessels may overlap with clutter. Accordingly, integrating RCCA at the deep semantic stage of -Net strengthens spatial reasoning in challenging maritime scenes.

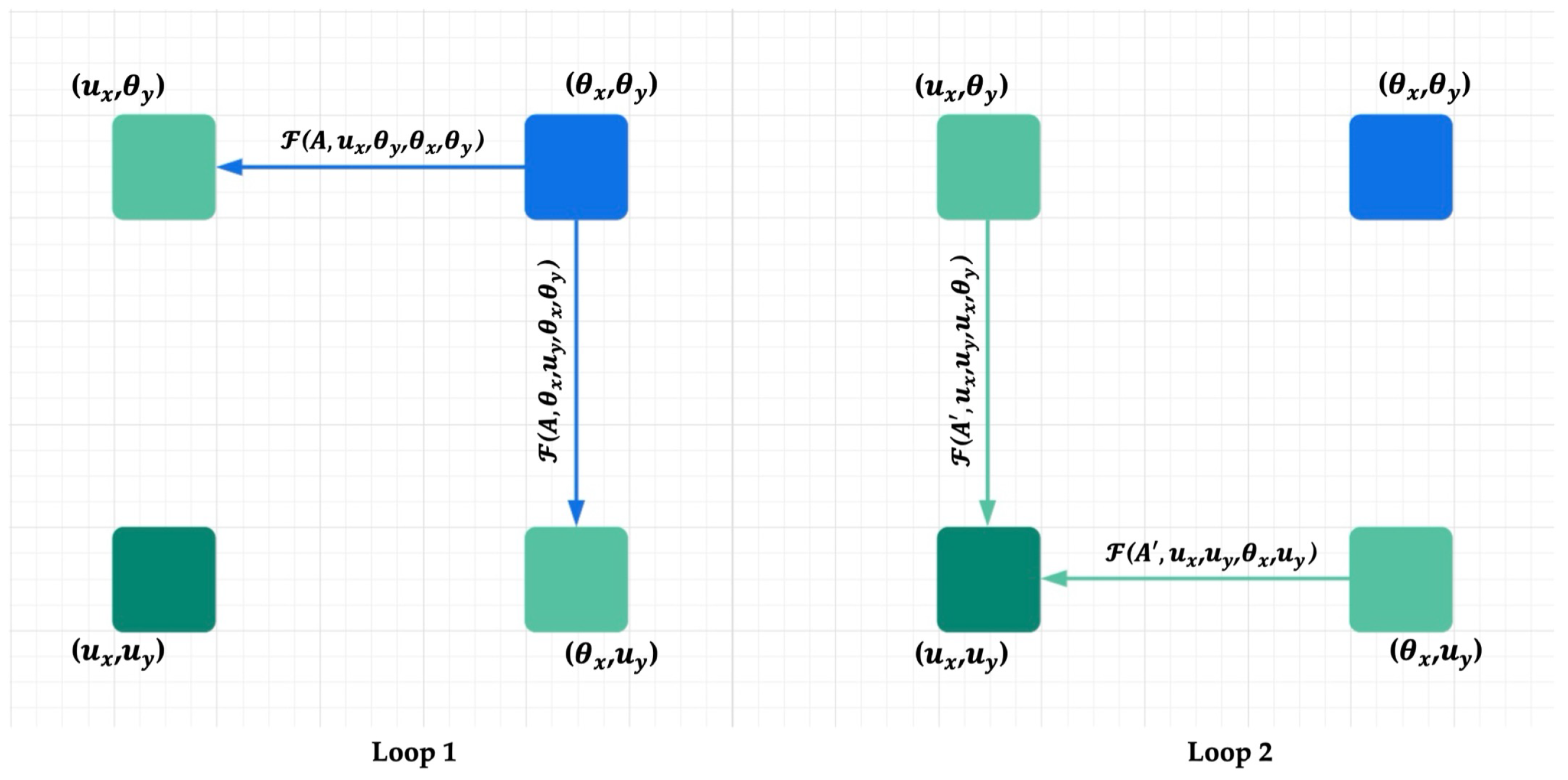

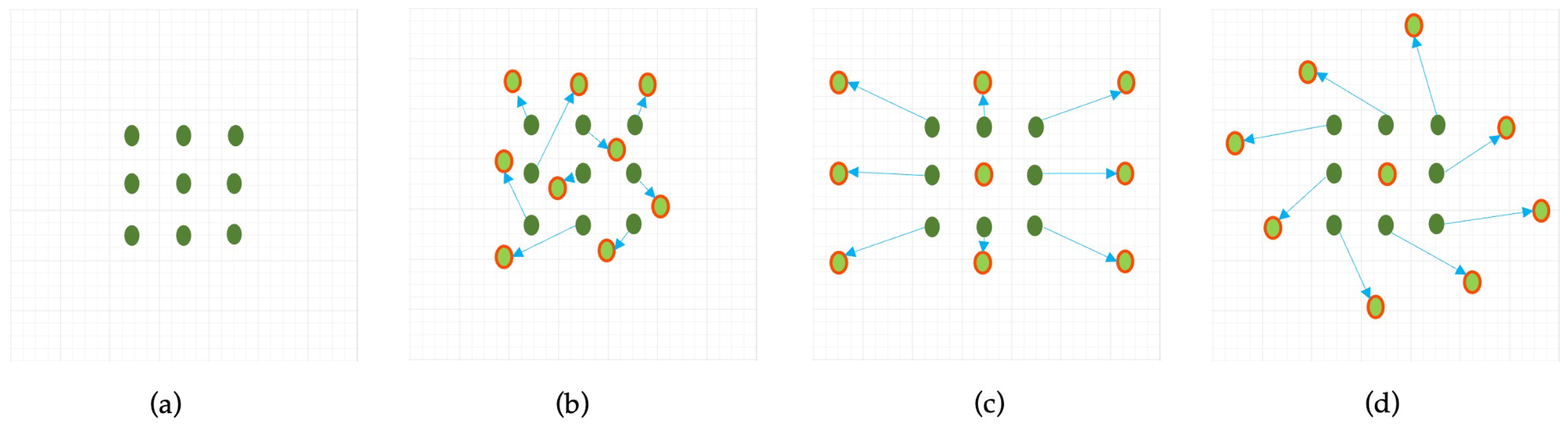

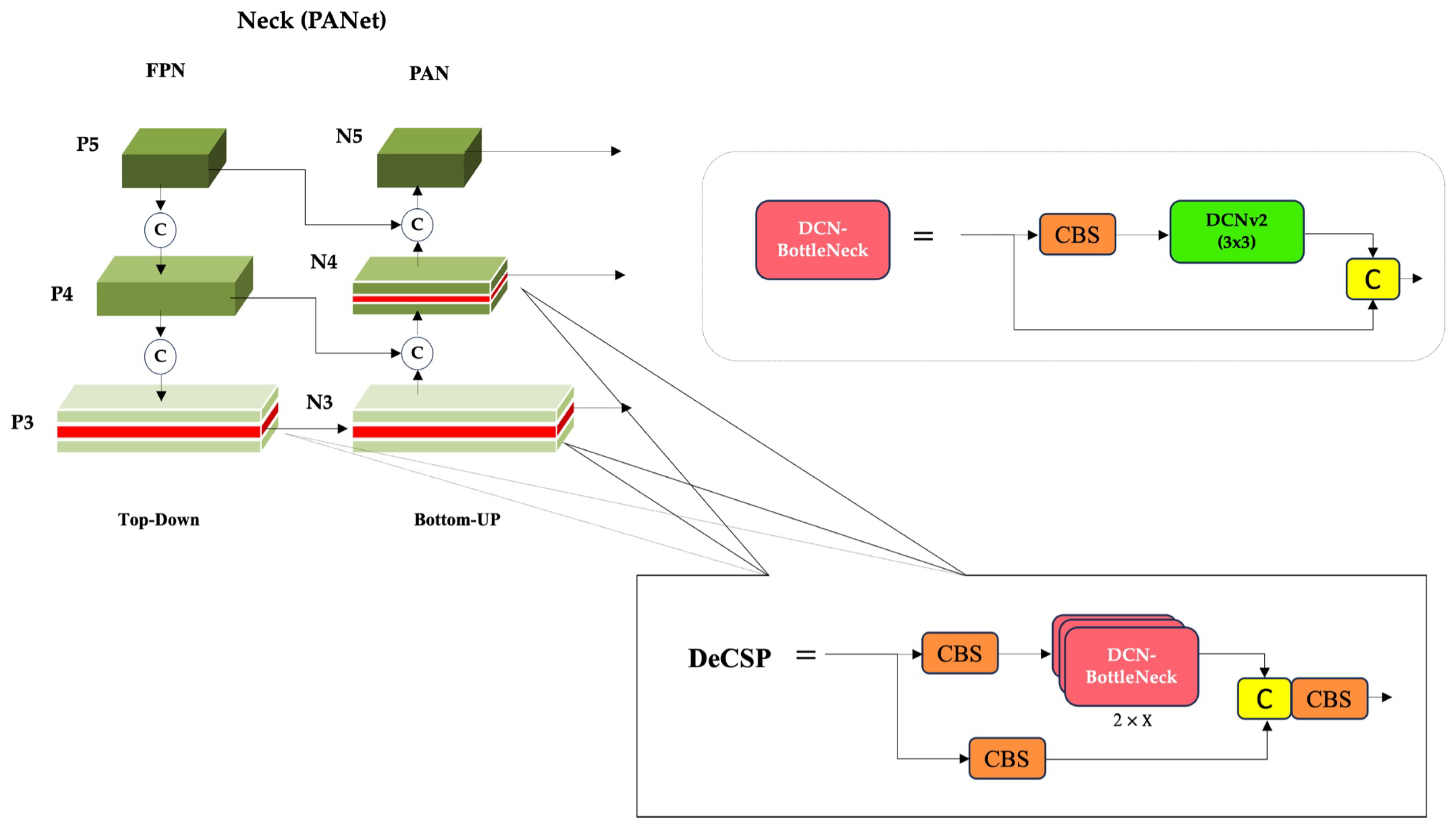

3.3. DCNv2-Enhanced Neck: Adaptive Geometry Modeling in Multi-Scale Fusion

To enhance spatial adaptability in multi-scale feature fusion, DRC2-Net integrates DCNv2 into the CSP modules of the neck. In contrast to standard convolutions that utilize a fixed grid, DCNv2 introduces learnable offsets which dynamically adjust the sampling positions based on the input’s local geometry. This allows the network’s receptive field to adaptively align with the diverse shapes and orientations characteristic of maritime targets.

As illustrated in

Figure 8, deformable convolutions are integrated at three critical points in the neck: C3–N3 and C3–N4 in the bottom-up path, and C3–P3 in the top-down path, where accurate multi-scale feature alignment is essential. This enhancement is implemented through a custom Deformable CSP (DeCSP) layer, which preserves the original CSP architecture’s split–transform–merge strategy. Specifically, the standard

convolutions within the bottleneck blocks are replaced with DCNv2 layers, forming a DCN-Bottleneck. By embedding these DCN-Bottlenecks within the CSP structure, the network gains a superior capacity to capture rotated and distorted ship features, all while maintaining a low computational overhead. Instead of altering entire residual branches or replacing all convolutions—which provided only marginal benefits in preliminary trials—we adopt a selective design: only the 3 × 3 convolution inside the bottleneck block is substituted with a DCNv2 layer, forming a modular DeCSP block.

This modularity ensures that the original CSP structure can be preserved or extended with minimal architectural disruption. The two bottom-up insertions enhance early semantic fusion by adapting receptive fields to local geometric variations, while the top-down insertion reinforces high-level refinement, capturing global shape consistency. Together, these placements complement each other by balancing low-level adaptability with high-level contextual reasoning. By combining this geometric flexibility with the efficiency of CSP-Darknet, the design strengthens multi-scale feature fusion and significantly improves robustness to hard samples in SAR imagery.

This dual strategy leverages semantic attention and spatial adaptability in a complementary manner, effectively addressing both contextual ambiguity and geometric deformation. Importantly, the enhancements preserve the original YOLOX-Tiny detection head, ensuring that DRC2-Net retains its real-time inference speed and compact size.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed -Net through three complementary analyses. These include ablation experiments validating the contribution of each proposed module, benchmark comparisons with state-of-the-art lightweight detectors on the SSDD dataset, and scene-level assessments on the iVision-MRSSD dataset. Together, these evaluations demonstrate the model’s architectural effectiveness, generalization capability, and operational robustness for SAR ship detection.

To ensure principled integration of the proposed attention mechanism, an initial comparison was conducted with representative alternatives. Specifically, CBAM and SimAM were inserted at the same spatial position as RCCA for fair evaluation. This preliminary experiment confirmed that RCCA provides stronger contextual reasoning and higher stability under cluttered SAR conditions, supporting its adoption in the final network design.

A structured ablation study was then performed to quantify the contribution of each architectural enhancement. Across three experiments and eight configurations, the analysis isolated the effects of contextual attention and deformable convolutions within both the backbone and the neck. The final configuration integrated the most effective modules into the complete -Net, confirming their complementary roles in strengthening multi-scale feature representation and improving overall detection accuracy.

Table 2 reports the results of Experiment 1, which examines the effect of contextual attention mechanisms embedded within the backbone. Using the default YOLOX-Tiny (BB-0) as the baseline, several enhanced variants were evaluated by inserting attention modules immediately after the SPP bottleneck in the Dark5 stage. These configurations include BB-1 (CBAM), BB-2 (SimAM), BB-3 (CCA), and BB-4 (RCCA).

To systematically evaluate the impact of attention mechanisms within the YOLOX-Tiny backbone, five configurations were tested by inserting different modules after the SPP bottleneck in the Dark5 stage. The baseline (BB-0), without attention, provided a solid reference with mAP@50 of 90.89%, AP of 61.32%, and F1-score of 94.57%, establishing the baseline representation capability for SAR ship detection. Integrating CBAM (BB-1) yielded the highest precision (97.30%) but reduced AP to 59.71% (%), indicating improved confidence but limited adaptability in cluttered SAR scenes. SimAM (BB-2) achieved an AP of 60.02% and the highest (89.63%) but only marginal recall improvement (92.86%), suggesting limited generalization across scales. CCA (BB-3) introduced criss-cross feature interactions, producing balanced results (AP = 61.21%, recall = 92.12%) yet underperforming for small and large targets. In contrast, RCCA (BB-4) delivered the best overall results: AP = 61.92% (+0.60%), recall = 93.04% (+0.55%), and = 84.21% (+5.26%), while maintaining strong precision (96.58%) and competitive mAP@50 (91.09%). RCCA thus demonstrates superior contextual reasoning and scale adaptability with minimal computational cost. Originally validated on the COCO segmentation benchmark, it shows consistent advantages when adapted to SAR imagery, confirming its suitability for integration into the final -Net architecture.

As shown in

Figure 9, the Precision–Recall curve confirms this advantage: the RCCA-enhanced backbone sustains higher precision across a broad recall range, yielding superior AP@50. This visual evidence reinforces the quantitative findings, validating RCCA’s role in strengthening spatial–semantic representation and supporting its integration into the final

-Net structure.

Table 3 presents the results of Experiment 2, which evaluates the impact of deformable convolutional enhancements within the neck while reusing the same backbone variants from Experiment 1. Three neck configurations were explored: NK-0 denotes the original YOLOX neck; NK-1 integrates two DeCSP blocks into the bottom-up path at C3_N3 and C3_N4; and NK-2 extends this design by adding a third DeCSP block in the top-down path at C3_P3. This setup isolates the contribution of the neck, particularly the influence of DCNv2, on multi-scale feature fusion and spatial adaptability, while maintaining consistency in the backbone structure across all variants.

The baseline configuration (NK-0), which employs standard CSPLayers, establishes strong performance with the highest AP (61.32%) and (89.97%), confirming its suitability for small-target detection. Introducing two DeCSP blocks in the bottom-up path (NK-1) increases precision to 97.48% and raises to 84.21% (+5.26% over baseline), indicating that adaptive sampling improves localization for larger and irregular ship targets. However, the overall AP slightly decreases (60.53%), suggesting that the deformable design reduces sensitivity to small-scale targets.

Extending the architecture with a third DeCSP block in the top-down path (NK-2) further boosts to 90.43% (+3.20%) and to 89.47% (+10.52%), demonstrating enhanced multi-scale refinement and geometric adaptability. Nevertheless, this configuration results in reduced mAP@50 (−1.29%) and a decline in (−3.24%), confirming that excessive deformability can weaken fine-grained detection in cluttered SAR backgrounds. Overall, these results highlight that while deformable convolutions benefit mid-to-large targets, careful balancing is required to preserve small-target accuracy.

Table 4 presents the results of Experiment 3, which integrates the most effective components identified in the earlier studies—namely, the RCCA-augmented backbone (BB-4) and the 3-DeCSP neck configuration (NK-2)—into a unified architecture, referred to as

-Net. While the neck-only experiments indicated that deformable convolutions primarily benefit mid-to-large targets at the expense of small-scale accuracy, their combination with RCCA effectively balances this trade-off. In the final design, the three DeCSP modules work in harmony with RCCA, enhancing multi-scale representation without sacrificing the lightweight nature of the YOLOX-Tiny foundation.

Experiment 3 validates the complementary synergy between global contextual attention and deformable convolutional sampling. The integrated design enhances both semantic representation and spatial adaptability, yielding consistent improvements across scales. Specifically, -Net achieves gains of +0.98% in mAP@50, +0.61% in overall AP, and +0.49% in F1-score over the baseline YOLOX-Tiny. The improvements are particularly evident for small-object detection (: +1.18%) and large-object detection (: +10.52%). Overall, -Net represents a focused architectural refinement of YOLOX-Tiny, in which RCCA strengthens long-range contextual reasoning while DeCSP modules adaptively refine multi-scale spatial features. These enhancements produce a lightweight yet powerful SAR ship detector that balances efficiency with robustness, making it suitable for real-time maritime surveillance in complex environments.

5.1. Comparative Evaluation with Lightweight and State-of-the-Art SAR Detectors on SSDD

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed

-Net, we benchmarked it against a range of representative object detectors. These include mainstream YOLO variants such as YOLOv5 [

43], YOLOv6 [

44], YOLOv3 [

45], YOLOv7-tiny [

46], and YOLOv8n [

47], as well as lightweight SAR-specific models including YOLO-Lite [

48] and YOLOSAR-Lite [

49].

As summarized in

Table 5,

-Net achieves the highest F1-score of 95.06%, outperforming all baseline detectors. It also attains the highest precision (96.77%) and a strong recall (93.41%), highlighting its ability to minimize false positives while maintaining sensitivity to true targets. These results demonstrate that the integration of contextual reasoning and geometric adaptability in

-Net leads to superior SAR ship detection performance across diverse conditions.

As summarized, the proposed -Net achieves superior performance compared with both general-purpose and SAR-specific lightweight detectors. It attains the highest F1-score of 95.06%, reflecting an optimal balance between precision (96.77%) and recall (93.41%), achieved with only 5.05M parameters and 9.59 GFLOPs. This demonstrates that the model maintains high accuracy while remaining computationally efficient. Compared to mainstream detectors such as YOLOv5 and YOLOv8n, which achieve precision above 95% but do not report F1-scores, -Net offers a more complete and balanced performance profile. Although YOLOv7-tiny exhibits the highest recall (94.9%), its relatively lower precision (92.9%) and lack of F1-score reporting limit a fair comparative assessment. In contrast, -Net consistently outperforms domain-specific lightweight models. YOLO-Lite achieves an F1-score of 93.39% and YOLOSAR-Lite 91.75%, yet both fall short of -Net’s accuracy while maintaining similar or larger parameter counts. With its compact architecture (5.05M parameters) and moderate computational cost (9.59 GFLOPs), -Net achieves an effective balance between detection accuracy and efficiency, demonstrating its suitability for real-time SAR ship detection in resource-constrained environments. While the model achieves an indicative inference rate of approximately 52 FPS on an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU, this value is hardware-dependent and not a definitive measure of architectural efficiency. Therefore, FLOPs and parameter count remain the primary, hardware-independent indicators of computational complexity, confirming -Net’s lightweight design. These results collectively establish a strong foundation for broader validation on diverse and higher-resolution datasets such as iVision-MRSSD, discussed in the following section.

5.2. Quantitative Evaluation on the iVision-MRSSD Dataset

We further evaluated the proposed model on the recently introduced iVision-MRSSD dataset, a high-resolution SAR benchmark released in 2023. In contrast to SSDD, iVision-MRSSD presents greater challenges due to its wide range of ship scales, dense coastal clutter, and highly diverse spatial scenarios, making it an appropriate benchmark for testing robustness in realistic maritime surveillance applications. A notable limitation of this domain is that many existing SAR ship detection models are not publicly available or lack detailed implementation specifications, hindering reproducibility. To ensure a fair and meaningful comparison, we therefore adopt uniform experimental settings wherever feasible and report the best available metrics as documented in the respective original publications. As shown in

Table 6, recent lightweight detectors such as YOLOv8n (58.1%), YOLOv11n (57.9%), and YOLOv5n (57.5%) achieve the highest overall Average Precision (AP) on the iVision-MRSSD dataset. These results indicate notable progress in overall detection capability; however, they do not fully capture robustness across different target scales.

A detailed scale-wise evaluation highlights the advantage of the proposed -Net, which achieves 71.56% , 84.15% , and 78.43% . These results significantly surpass competing baselines, particularly in detecting small- and medium-sized ships that are often missed by other models due to resolution loss and heavy background clutter in SAR imagery. In comparison, YOLOv8n and YOLOv11n report strong overall AP, but their values (51.5% and 52.1%, respectively) reveal persistent limitations in small-object detection.

Although -Net attains a slightly lower overall AP than YOLOv8n on the iVision-MRSSD dataset, this difference arises from the dataset’s heterogeneity and the model’s conservative confidence threshold, which prioritize precision and reliability under cluttered maritime conditions. This reflects -Net’s design focus on scale-aware robustness rather than aggregate metric optimization, aligning with the practical demands of SAR-based detection. By combining RCCA for global contextual reasoning with DeCSP modules for adaptive receptive fields, the framework maintains consistent accuracy across ship scales while ensuring efficient and reliable operation in complex maritime environments.

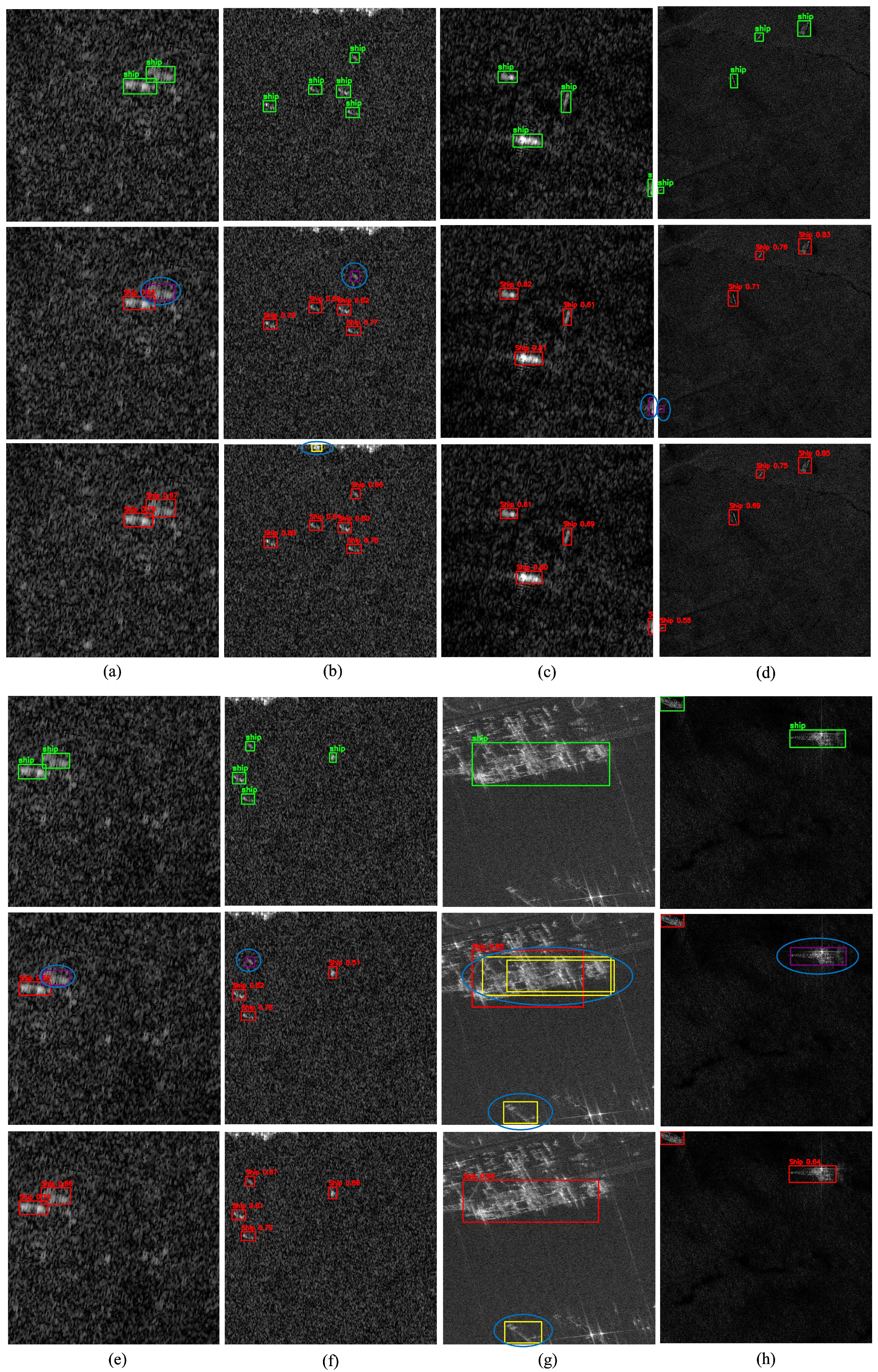

To qualitatively assess detection performance, representative scenes from the SSDD dataset are illustrated in

Figure 10. Columns (a–i) cover diverse maritime conditions, including open-sea scenarios, nearshore environments, and multi-scale ship distributions within cluttered backgrounds. These examples emphasize the inherent challenges of SAR-based ship detection and provide visual evidence of the improvements achieved by the proposed

-Net.

In all qualitative figures presented in this paper, each column corresponds to a distinct SAR scene, while the three rows represent different visualization layers: the top row displays ground-truth annotations, the middle row shows predictions from the baseline YOLOX-Tiny model, and the bottom row illustrates results from the proposed -Net. To maintain visual consistency, a unified color scheme is used across all examples: green boxes indicate ground-truth targets, red boxes denote correct detections, yellow boxes represent false positives, purple boxes highlight missed targets, and blue circles mark critical errors.

False alarms (yellow boxes) occur most frequently in open-sea and offshore scenes (

Figure 10a–d), where wakes and wave patterns often resemble ships and mislead conventional detectors.

-Net effectively mitigates these errors through deformable convolutions, which adapt receptive fields to better differentiate ships from surrounding clutter. Missed detections (purple boxes) are primarily observed in

Figure 10e,f,h, typically involving small or low-contrast vessels. Notably, across all illustrated cases,

-Net missed only one target in

Figure 10g, demonstrating the effectiveness of RCCA in leveraging contextual cues to recover ambiguous or fragmented ships. Overall, these findings confirm that

-Net delivers higher reliability by reducing false positives while enhancing sensitivity to challenging ship instances.

To further validate the generalization capability of the proposed -Net, instance-level visual comparisons were conducted across three representative sets of SAR scenes from the iVision-MRSSD dataset. These samples encompass data from six distinct satellite sensors and are grouped into three major scenarios, each highlighting specific detection challenges.

Figure 11 shows Scenario A (a–e), covering shorelines, harbors, and congested maritime zones with dense vessel clusters and coastal infrastructure. These conditions often trigger false alarms and mislocalizations, particularly for small, low-resolution ships affected by scale variation and background interference. While the baseline YOLOX-Tiny frequently misses or misclassifies such targets, the proposed

-Net achieves more precise localization, especially near image edges, demonstrating greater robustness in challenging coastal environments.

Figure 12 presents Scenario B (a–f), which depicts densely packed ships in far-offshore environments. These conditions are characterized by low signal-to-clutter ratios, heavy speckle noise, and ambiguous scattering patterns, all of which make target visibility and discrimination difficult. In such challenging scenes, missed detections frequently arise from faint radar returns and poorly defined object boundaries. Compared with the baseline, the proposed

-Net demonstrates stronger resilience to these issues, achieving more reliable detection under severe offshore clutter.

Figure 13 presents the final group of test scenes (Scenario C), featuring severe speckle noise, clutter, and ambiguous scattering patterns typical of moderate-resolution SAR imagery and rough sea states. These challenging conditions often lead to false positives and missed detections in baseline models. By contrast, the proposed model demonstrates stronger robustness, accurately localizing vessels despite degraded image quality and complex backgrounds.

In contrast, the proposed -Net demonstrates enhanced robustness by combining deformable convolutions with contextual attention, effectively suppressing spurious responses and improving target discrimination. The qualitative results confirm -Net’s ability to localize small and multi-scale vessels even under adverse imaging conditions, highlighting its generalization capability across offshore, coastal, and noise-dominant scenarios in the iVision-MRSSD dataset.

A quantitative summary of detection performance on the iVision-MRSSD dataset, expressed in terms of correct detections, false alarms, and missed targets, is provided in

Table 7. The results demonstrate the improved performance of the proposed model across all scenarios. In Scenario A,

-Net achieves 94.4% detection accuracy (17/18) compared with 61.1% for YOLOX-Tiny. In Scenario B,

-Net reaches 95.7% (88/92) versus 83.7% for the baseline, reducing missed detections from 13 to 2. In the most challenging Scenario C, it attains 91.7% (22/24) versus 58.3% for YOLOX-Tiny. These results highlight the robustness of

-Net, particularly in cluttered and noise-dominant SAR environments, achieving up to a +33.4% gain in detection accuracy over the baseline.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented -Net, a lightweight and geometry-adaptive detection framework tailored for SAR ship detection. Built upon YOLOX-Tiny, the architecture integrates RCCA into the deep semantic stage of the backbone to enhance global contextual reasoning, and introduces DCNv2 modules within CSP-based fusion layers to improve geometric adaptability. This dual integration strengthens semantic continuity and spatial flexibility while maintaining real-time efficiency and a compact 5.05 M-parameter design.

On the SSDD dataset, -Net achieves clear performance gains over the baseline YOLOX-Tiny. The AP@50 increases by +0.9% (to 93.04%), by +1.31% (to 91.15%), by +1.22% (to 88.30%), and by +13.32% (to 89.47%). These improvements are obtained with only 5.05 M parameters and 9.59 GFLOPs, confirming the model’s efficiency and suitability for real-time applications. Consistent improvements are also observed on the more challenging iVision-MRSSD dataset, where the proposed model achieves detection accuracies of 94.4%, 95.7%, and 91.7% across Scenarios A, B, and C, respectively. These results surpass YOLOX-Tiny and demonstrate strong generalization across diverse maritime conditions. Qualitative visualizations further reinforce the model’s robustness under cluttered and low-contrast SAR environments.

Importantly, no single architecture can optimally address all SAR ship detection tasks. Effective frameworks must balance accuracy, computational efficiency, and adaptability to mission-specific requirements and environmental constraints. The proposed -Net establishes a favorable trade-off among these factors, achieving high accuracy with minimal parameters and moderate computational cost, thereby providing a practical and deployable solution for real-time SAR ship detection. Future research will focus on model pruning, quantization, and rotated bounding-box prediction to further enhance deployment efficiency and detection precision in complex maritime environments.