Time-Frequency-Based Separation of Earthquake and Noise Signals on Real Seismic Data: EMD, DWT and Ensemble Classifier Approaches

Highlights

- Time-frequency features extracted using EMD, DWT, and combined EMD+DWT effectively separate earthquake and noise signals.

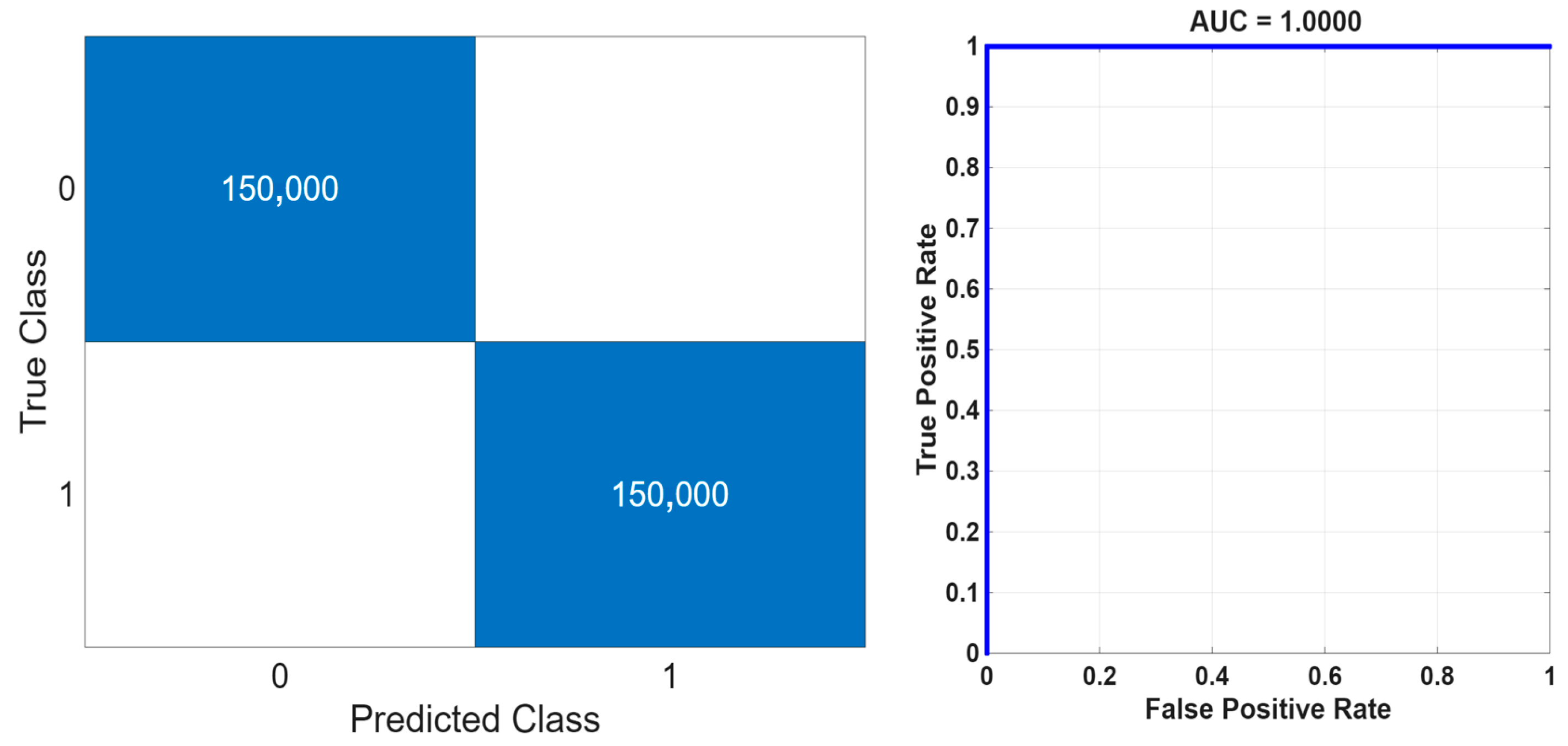

- Random Forest classifier with Lasso-selected EMD+DWT features achieved 100% accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity.

- Time-frequency-based feature extraction and selection improve real-time earth-quake detection.

- The approach provides a robust foundation for operational monitoring and ear-ly-warning systems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Study

1.2. Literature Gaps

1.3. Motivation

1.4. Innovations of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Normalization

2.3. Feature Extraction

2.3.1. Empirical Mode Decomposition

- All extreme points of the signal are determined.

- Upper and lower envelope curves are created by cubic spline interpolation of the extremum points.

- The average of the envelope curves m(t) is calculated.

- The difference signal d(t) = x(t) − m(t) is obtained.

- The same procedure is repeated on the remaining signal m(t) and new IMFs are extracted.

2.3.2. Discrete Wavelet Transform

2.4. Feature Selection

2.4.1. ReliefF Algorithm

- m: number of randomly selected samples.

- : ith example.

- : ith example class.

- : probability of class c in the dataset.

- diff(A,x,x′): the difference in the feature A between x and x′ (for continuous data, the absolute difference is usually taken).

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode of the ReliefF algorithm |

| Input: Feature matrix with instances and features extracted via EMD and DWT; class labels ; parameters (neighbors), (sampled instances) |

| Output: Feature importance scores |

| 1: Load the feature matrix and class labels |

| 2: Initialize weights for each feature |

| 3: For to do |

| 4: Randomly select an instance from |

| 5: Find nearest neighbors of the same class (hits) , |

| 6: For each class do |

| 7: Find nearest neighbors from class (misses) , |

| 8: End for |

| 9: For each feature do |

| 10: |

| 11: |

| 12: End for |

| 13: End for |

| 14: Return the feature weights as the importance scores |

2.4.2. Student t-Test

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode of the Student’s t-test algorithm |

| Input: Feature matrix extracted from signals using EMD and DWT; class labels ; significance level |

| Output: t-statistics , p-values, and conclusion for each feature |

| 1: For each feature , compute sample means: |

| 2: Compute sample variances: |

| 3: Compute pooled standard deviation (for independent samples, equal variance): |

| 4: Compute t-statistic for each feature: |

| 5: Compute degrees of freedom: |

| 6: Determine p-value from t-distribution with degrees of freedom |

| 7: Compare p-value to 0.05: If , reject feature discriminates Earthquake vs. Noise Else, fail to reject feature not significant |

| 8: Return t-statistics, p-values, and significance conclusion for all 154 features |

2.4.3. LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)

| Algorithm 3 Pseudocode of the LASSO algorithm |

| Input: Feature matrix (EMD + DWT features), class labels , regularization parameter |

| Output: Selected feature coefficients , feature importance |

| 1: Standardize the features in to have zero mean and unit variance |

| 2: Initialize coefficients for all features |

| 3: Solve the LASSO optimization problem: |

| 4: Iterate until convergence: Update for each feature using coordinate descent |

| 5: Identify selected features: Features with non-zero are considered important |

| 6: Return and feature importance ranking |

2.5. Classification Algorithms

2.5.1. Support Vector Machines

2.5.2. K-Nearest Neighbor

2.5.3. Decision Trees

2.5.4. Random Forest

2.5.5. Ensemble Bagged Trees

2.6. Performance Criteria

3. Results

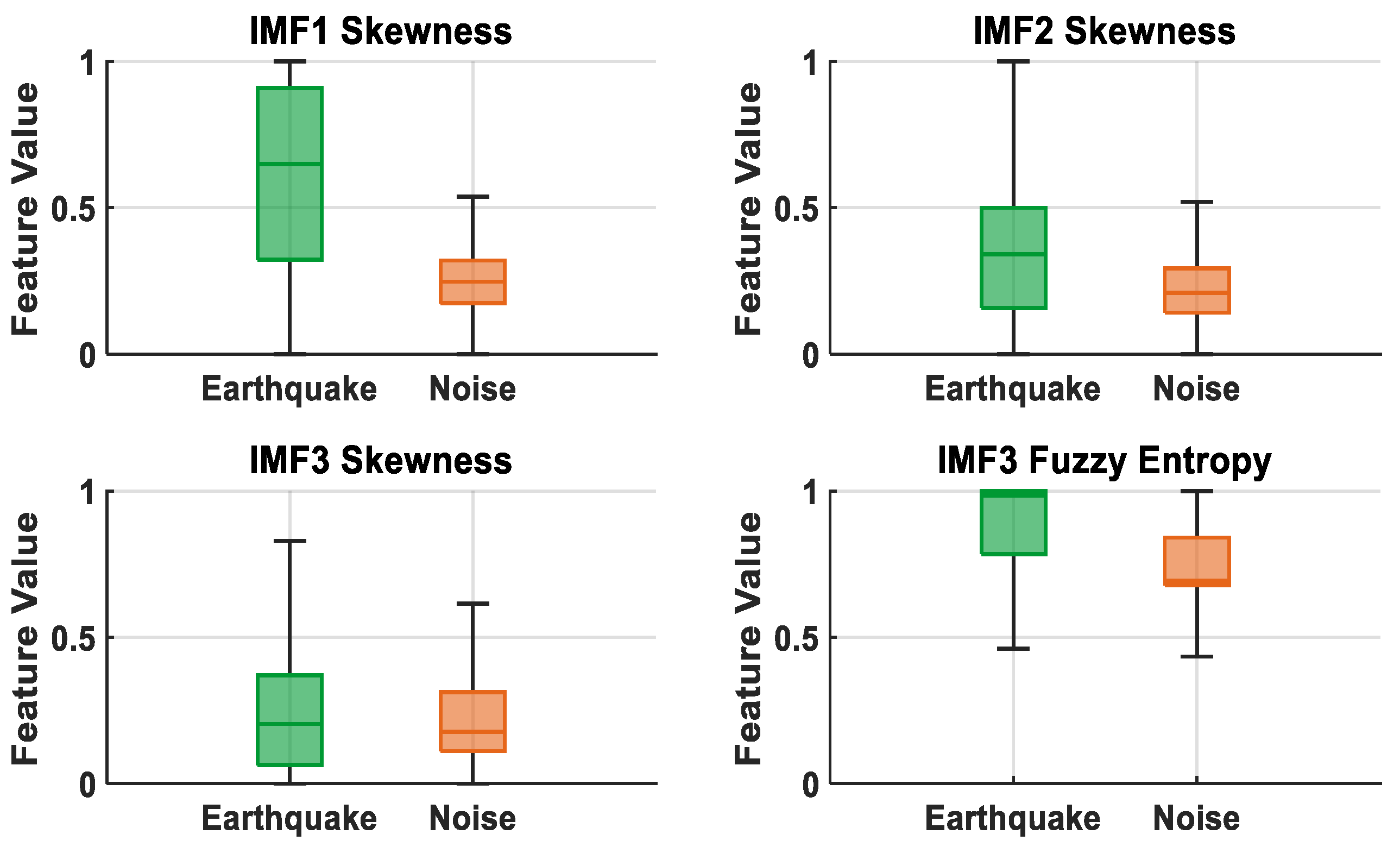

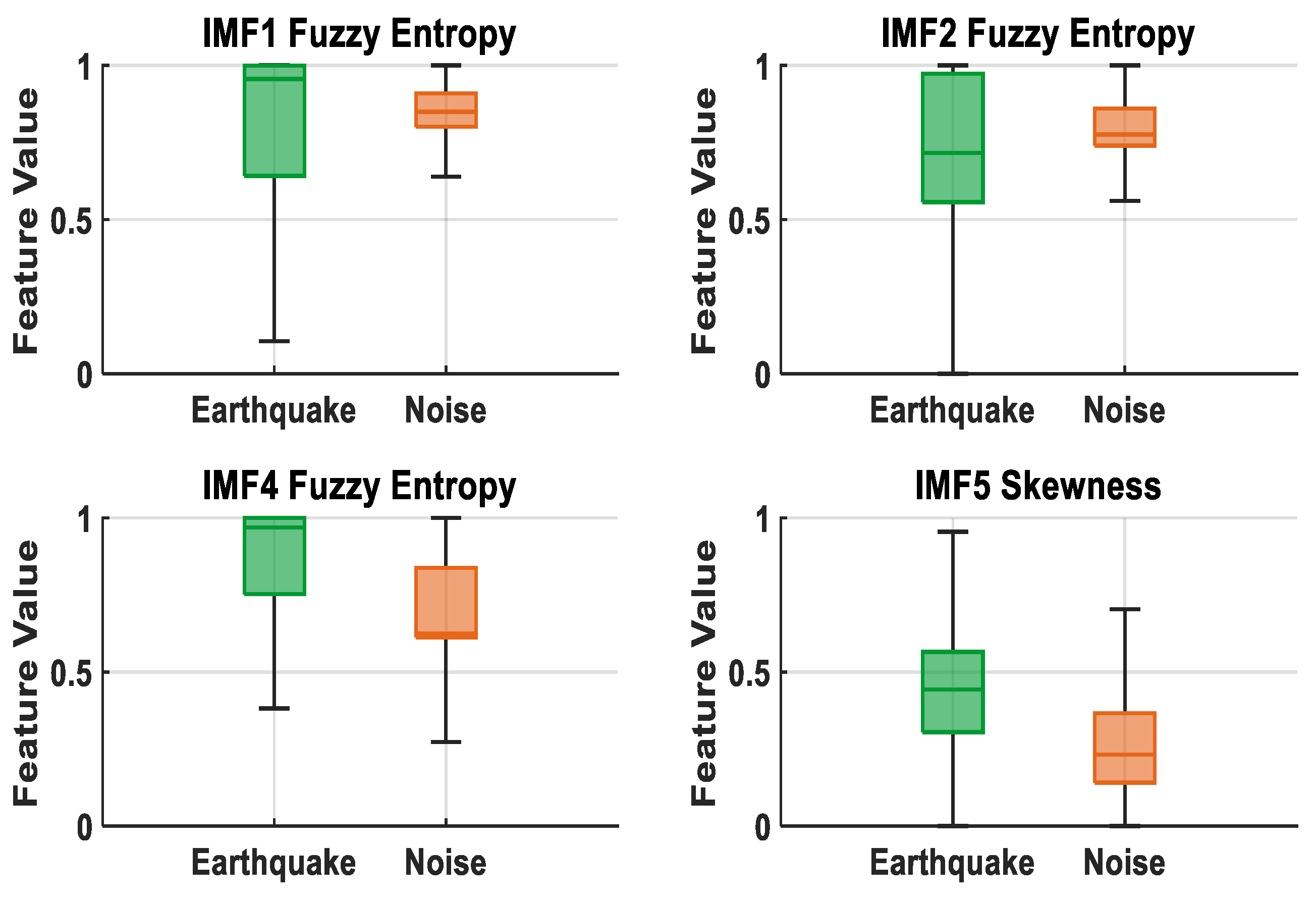

3.1. Performance Analysis of EMD and DWT Signals

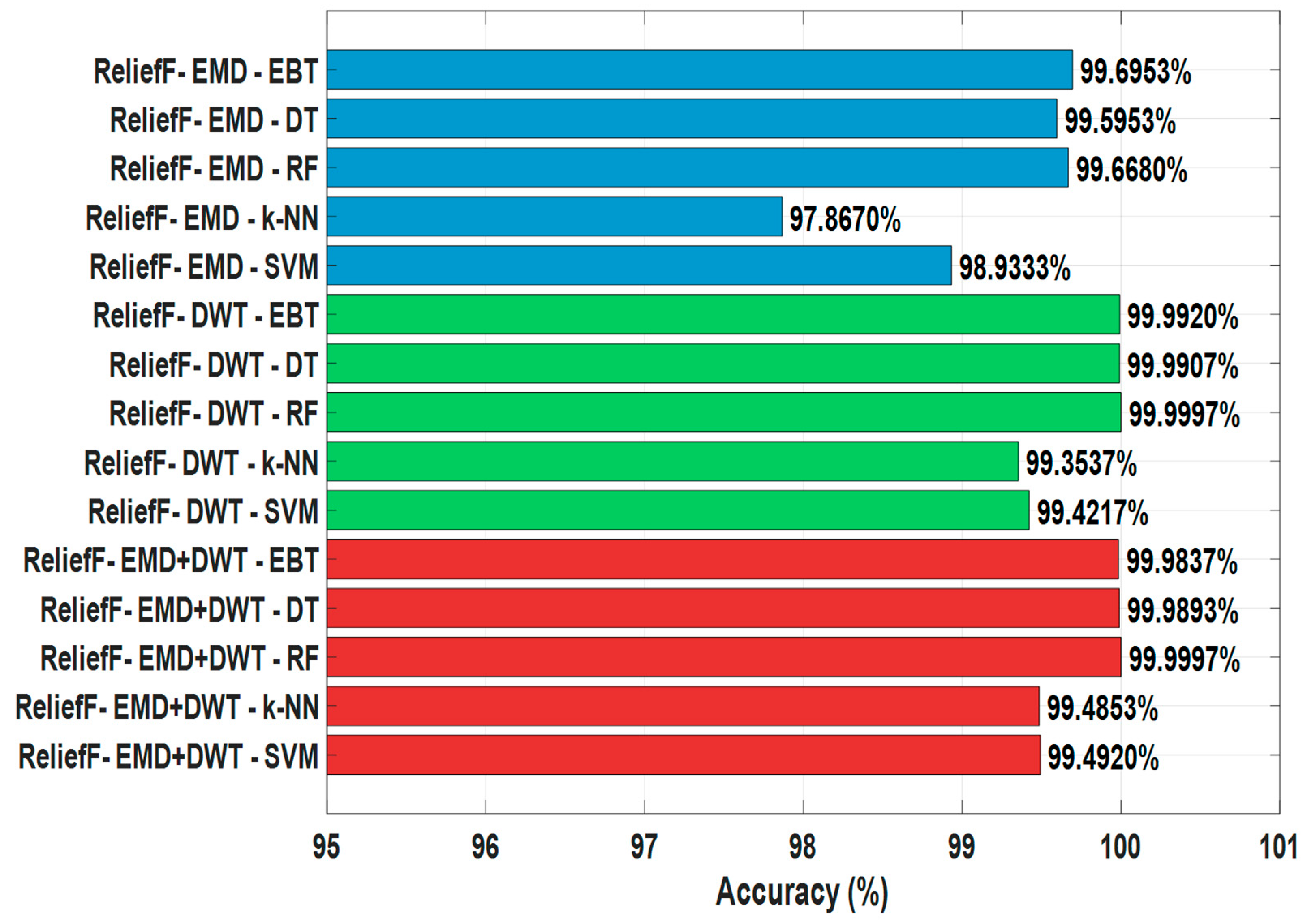

3.2. Performance Analysis of Feature Selection Algorithms

4. Discussion

- Achieving high accuracy on a larger, three-component dataset.

- Evaluating time and frequency domain features together.

- Feature selection and systematic comparison of different classifier combinations.

- Ensemble methods provide high generalization capability and stable performance.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanrı Karapınar, I.; Özsoy Özbay, A.E.; Kutlu, Z.N.; Yazgan, A.U.; Kılıç, İ.E. Seismic vulnerability analysis incorporating local site amplification effects in shallow, varying bedrock depths. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 16013–16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, H.; Cooper, J.D.; Imbsen, R.A.; Piskin, H.; Inal, F.; Tiras, A. The November 1999 Duzce Earthquake: Post-Earthquake Investigation of the Structures on the TEM (No. FHWA-RD-00-146); United States Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Lay, T.; Kanamori, H.; Ammon, C.J.; Nettles, M.; Ward, S.N.; Aster, R.C.; Sipkin, S. The great Sumatra-Andaman earthquake of 26 December 2004. Science 2005, 308, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DesRoches, R.; Comerio, M.; Eberhard, M.; Mooney, W.; Rix, G.J. Overview of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2011, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, N.; Takahashi, T.; Yasuda, T.; Yanagisawa, H. Survey of 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami inundation and run-up. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L00G07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouac, J.P.; Meng, L.; Wei, S.; Wang, T.; Ampuero, J.P. Lower edge of locked Main Himalayan Thrust unzipped by the 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socquet, A.; Hollingsworth, J.; Pathier, E.; Bouchon, M. Evidence of supershear during the 2018 magnitude 7.5 Palu earthquake from space geodesy. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.; Dutta, R.; Vernon, A.; Vajedian, S. Complex rupture and triggered aseismic creep during the 14 August 2021 Haiti earthquake from satellite geodesy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikuddembe, J.K.; Reinhardt, J.D.; Vahid, G.; Di, B. A scoping review of post-earthquake healthcare for vulnerable groups of the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquakes. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Bai, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y. Earthquake signal detection using a multiscale feature fusion network with hybrid attention mechanism. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, 240, 988–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Khan, I.; Kwon, Y.W. A transformer-based real-time earthquake detection framework in heterogeneous environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Ma, Z. A Novel Time–Frequency Similarity Method for P-Wave First-Motion Polarity Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Choi, S.; Kwon, Y.W. Earthquake detection in a static and dynamic environment using supervised machine learning and a novel feature extraction method. Sensors 2020, 20, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhexebay, D.; Skabylov, A.; Ibraimov, M.; Khokhlov, S.; Agishev, A.; Kudaibergenova, G.; Agishev, A. Deep learning for early earthquake detection: Application of convolutional neural networks for P-wave detection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Meier, M.A.; Hauksson, E.; Zhan, Z.; Andrews, J. Machine learning seismic wave discrimination: Application to earthquake early warning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 4773–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štajduhar, I. The choice of time–frequency representations of non-stationary signals affects machine learning model accuracy: A case study on earthquake detection from LEN-DB data. Mathematics 2022, 10, 965. [Google Scholar]

- Özkaya, S.G.; Baygın, N.; Barua, P.D.; Singh, A.R.; Bajaj, M.; Baygın, M.; Doğan, S.; Tuncer, T.; Acharya, U.R. Most complicated lock pattern-based seismological signal classification. Neurocomputing 2023, 528, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.C.A.; McLaren, J.D.A.; Shearer, P.M. Classifying seismograms using the FastMap algorithm and support vector machines. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuncay, H.; de Lorenzo, A.; Costa, G. Deep learning based earthquake and vehicle detection algorithm. J. Seismol. 2025, 29, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESM records from Java Island, Indonesia (2006–2009). Engineering strong motion data analysis with limited samples. Indones. J. Earthq. Eng. 2006–2009, 5, 45–53.

- Habbak, M.; El-Sayed, A.; Mahmoud, S. Classification of earthquake and quarry blast signals using CNN with attention mechanism: A case study from the Egyptian National Seismic Network. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Vasti, M.; Dev, A. Deep learning-based classification of seismic events using waveform data. Adv. Appl. Discret. Math. 2025, 42, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuncay, H.; Yildiz, A.; Demir, F. Seismic signal discrimination of earthquakes and quarry blasts in North-East Italy using deep neural networks. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2024, 181, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, F.; Jozinović, D.; Cammarano, F.; Michelini, A.; Boschi, L. Local earthquakes detection: A benchmark dataset of 3-component seismograms built on a global scale. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett, B.L.N.; Engdahl, E.R. Traveltimes for global earthquake location and phase identification. Geophys. J. Int. 1991, 105, 429–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, Y.E.; Narin, A. Comparison of classification algorithms for COVID-19 detection using cough acoustic signals. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.04872. [Google Scholar]

- Rilling, G.; Flandrin, P.; Goncalves, P. On empirical mode decomposition and its algorithms. In Proceedings of the IEEE-EURASIP Workshop on Nonlinear Signal and Image Processing (NSIP-03), Grado, Italy, 8–11 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosh, M.; Singh, P.; Sadhu, A. Empirical mode decomposition and its variants: A review with applications in structural health monitoring. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, C.E.; Walnut, D.F. Continuous and discrete wavelet transforms. SIAM Rev. 1989, 31, 628–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, G.; Zeebaree, D.Q. The applications of discrete wavelet transform in image processing: A review. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2020, 1, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, Y.E.; Narin, A. COVID-19 detection with traditional and deep features on cough acoustic signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Jhou, J.E.; Bai, Y.M.; Chen, M.H.; Tu, P.C.; Wu, Y.T. Brain functional networks and structures that categorize type 2 bipolar disorder and major depression. Prog. Brain Res. 2024, 290, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, U.; Pandey, C.M.; Mishra, P.; Pandey, G. Application of Student’s t-test, analysis of variance, and covariance. Ann. Cardiac Anaesth. 2019, 22, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, E.H. Who was a student and why do we care so much about his t-test? J. Surg. Res. 2004, 118, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A. LASSO regression. J. Br. Surg. 2018, 105, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamzawi, R.; Ali, H.T.M. The Bayesian adaptive lasso regression. Math. Biosci. 2018, 303, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Yang, Q.; Chen, S. SVM: Support vector machines. In The Top Ten Algorithms in Data Mining; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2009; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.L.; Jiang, B.; Lu, J.; Hua, J.; Swamy, M.N.S. Exploring kernel machines and support vector machines: Principles, techniques, and future directions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wang, H.; Bell, D.; Bi, Y.; Greer, K. KNN model-based approach in classification. In OTM Confederated International Conferences "On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems"; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 986–996. [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, L.; Maimon, O. Decision trees. In Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery Handbook; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 165–192. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, R.U.; Yapıcı, İ.S. A novel hybrid approach to improving obesity prediction. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 4843–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Szymczak, S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. Ensemble methods: Bagging and random forests. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 933–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Alsalemi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. Robust event-based non-intrusive appliance recognition using multi-scale wavelet packet tree and ensemble bagging tree. Appl. Energy 2020, 267, 114877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutschmann, T.M.; Kinzel, L.; Ter Laak, A.; Baumann, K. Large-scale evaluation of k-fold cross-validation ensembles for uncertainty estimation. J. Cheminform. 2023, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narin, A.; Özer, M.; İşler, Y. Effect of linear and non-linear measurements of heart rate variability in prediction of PAF attack. In Proceedings of the 2017 25th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Antalya, Turkey, 15–18 May 2017; IEEE: Ankara, Turkey, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Class | Number of Data | Total | Data Length (Samples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earthquake | 150,000 | 300,000 | 540 |

| Noise | 150,000 | 540 |

| Predicted Class | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||

| Real Class | Negative | TN True Negative | FP False Positive |

| Positive | FN False Negative | TP True Positive | |

| Feature Extraction Method/s | Classifier | Runtime (s) | Acc (%) | Spe (%) | Pre (%) | Rec (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | EBT | 72 | 99.5907 | 99.3580 | 99.3610 | 99.8233 | 99.5916 |

| EMD | DT | 15 | 99.1603 | 99.1620 | 99.1620 | 99.1587 | 99.1603 |

| EMD | RF | 65 | 99.6330 | 99.4100 | 99.4126 | 99.8560 | 99.6338 |

| EMD | k-NN | 28 | 98.2487 | 98.9613 | 98.9463 | 97.5360 | 98.2361 |

| EMD | SVM | 136 | 98.0567 | 97.3687 | 97.4044 | 98.7447 | 98.0699 |

| DWT | EBT | 83 | 99.9860 | 99.9767 | 99.9767 | 99.9953 | 99.9860 |

| DWT | DT | 18 | 99.9957 | 99.9960 | 99.9960 | 99.9953 | 99.9957 |

| DWT | RF | 75 | 99.9997 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 100.0000 | 99.9997 |

| DWT | k-NN | 33 | 98.8073 | 98.1467 | 98.1708 | 99.4680 | 98.8152 |

| DWT | SVM | 171 | 97.1357 | 95.6720 | 95.7951 | 98.5993 | 97.1770 |

| EMD+DWT | EBT | 160 | 99.9903 | 99.9900 | 99.9900 | 99.9907 | 99.9903 |

| EMD+DWT | DT | 36 | 99.9967 | 99.9967 | 99.9967 | 99.9967 | 99.9967 |

| EMD+DWT | RF | 151 | 99.9990 | 99.9980 | 99.9980 | 100.0000 | 99.9990 |

| EMD+DWT | k-NN | 55 | 98.8103 | 98.1493 | 98.1735 | 99.4713 | 98.8181 |

| EMD+DWT | SVM | 321 | 97.1243 | 95.6853 | 95.8060 | 98.5633 | 97.1651 |

| Feature Extraction Method/s | Classifier | Runtime (s) | Acc (%) | Spe (%) | Pre (%) | Rec (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | EBT | 24 | 99.2510 | 98.9807 | 98.9861 | 99.5213 | 99.2530 |

| EMD | DT | 6 | 98.2637 | 98.2927 | 98.2917 | 98.2347 | 98.2632 |

| EMD | RF | 22 | 99.2370 | 98.9667 | 98.9722 | 99.5073 | 99.2391 |

| EMD | k-NN | 28 | 98.4077 | 98.9827 | 98.9708 | 97.8327 | 98.3985 |

| EMD | SVM | 49 | 97.8197 | 96.6887 | 96.7619 | 98.9507 | 97.8441 |

| DWT | EBT | 26 | 99.9907 | 99.9873 | 99.9873 | 99.9940 | 99.9907 |

| DWT | DT | 6 | 99.9913 | 99.9900 | 99.9900 | 99.9927 | 99.9913 |

| DWT | RF | 26 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 |

| DWT | k-NN | 12 | 99.9753 | 99.9613 | 99.9613 | 99.9893 | 99.9753 |

| DWT | SVM | 59 | 99.9827 | 99.9747 | 99.9747 | 99.9907 | 99.9827 |

| EMD+DWT | EBT | 56 | 99.9997 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 | 99.9993 | 99.9997 |

| EMD+DWT | DT | 13 | 99.9863 | 99.9867 | 99.9867 | 99.9860 | 99.9863 |

| EMD+DWT | RF | 53 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 |

| EMD+DWT | k-NN | 17 | 99.9587 | 99.9253 | 99.9254 | 99.9920 | 99.9587 |

| EMD+DWT | SVM | 116 | 99.9507 | 99.9673 | 99.9673 | 99.9340 | 99.9507 |

| Feature Extraction Method/s | Classifier | Runtime (s) | Acc (%) | Spe (%) | Pre (%) | Rec (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | EBT | 22 | 99.1287 | 99.3100 | 99.3075 | 98.9473 | 99.1271 |

| EMD | DT | 5 | 98.4570 | 98.4107 | 98.4121 | 98.5033 | 98.4577 |

| EMD | RF | 21 | 99.2937 | 99.4860 | 99.4840 | 99.1013 | 99.2923 |

| EMD | k-NN | 26 | 97.8730 | 99.0507 | 99.0278 | 96,6953 | 97.8477 |

| EMD | SVM | 46 | 98.9203 | 98.6173 | 98.6257 | 99.2233 | 98.9236 |

| DWT | EBT | 25 | 99.9883 | 99.9947 | 99.9947 | 99.9820 | 99.9883 |

| DWT | DT | 5 | 99.9947 | 99.9927 | 99.9927 | 99.9967 | 99.9947 |

| DWT | RF | 24 | 99.9990 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 99.9987 | 99.9990 |

| DWT | k-NN | 11 | 98.8063 | 98.1173 | 98.1429 | 99.4953 | 98.8145 |

| DWT | SVM | 59 | 97.1437 | 95.7087 | 95.8284 | 98.5787 | 97.1841 |

| EMD+DWT | EBT | 53 | 99.9900 | 99.9967 | 99.9967 | 99.9833 | 99.9900 |

| EMD+DWT | DT | 11 | 99.9897 | 99.9907 | 99.9907 | 99.9887 | 99.9897 |

| EMD+DWT | RF | 50 | 99.9987 | 100.0000 | 100.0000 | 99.9973 | 99.9987 |

| EMD+DWT | k-NN | 15 | 98.8140 | 98.1467 | 98.1711 | 99.4813 | 98.8219 |

| EMD+DWT | SVM | 109 | 97.1150 | 95.6433 | 95.7679 | 98.5867 | 97.1568 |

| Feature Extraction Method/s | Classifier | Runtime (s) | Acc (%) | Spe (%) | Pre (%) | Rec (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | EBT | 21 | 99.6953 | 99.9067 | 99.9063 | 99.4840 | 99.6947 |

| EMD | DT | 4 | 99.5953 | 99.6087 | 99.6086 | 99.5820 | 99.5953 |

| EMD | RF | 20 | 99.6680 | 99.9300 | 99.9296 | 99.4060 | 99.6671 |

| EMD | k-NN | 24 | 97.8670 | 99.0493 | 99.0263 | 96.6847 | 97.8415 |

| EMD | SVM | 43 | 98.9333 | 99.2233 | 99.2188 | 98.6433 | 98.9302 |

| DWT | EBT | 24 | 99.9920 | 99.9887 | 99.9887 | 99.9953 | 99.9920 |

| DWT | DT | 5 | 99.9907 | 99.9920 | 99.9920 | 99.9893 | 99.9907 |

| DWT | RF | 23 | 99.9997 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 100.0000 | 99.9997 |

| DWT | k-NN | 10 | 99.3537 | 99.2447 | 99.2463 | 99.4627 | 99.3544 |

| DWT | SVM | 57 | 99.4217 | 99.2367 | 99.2395 | 99.6067 | 99.4227 |

| EMD+DWT | EBT | 51 | 99.9837 | 99.9807 | 99.9807 | 99.9867 | 99.9837 |

| EMD+DWT | DT | 10 | 99.9893 | 99.9893 | 99.9893 | 99.9893 | 99.9893 |

| EMD+DWT | RF | 48 | 99.9997 | 99.9993 | 99.9993 | 100.0000 | 99.9997 |

| EMD+DWT | k-NN | 14 | 99.4853 | 99.3260 | 99.3281 | 99.6447 | 99.4862 |

| EMD+DWT | SVM | 105 | 99.4920 | 99.2973 | 99.3001 | 99.6867 | 99.4930 |

| Study | Dataset | Number of Data | Model | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Štajduhar (2022) [16] | LEN-DB | 150,000 seismograms | AlexNet (Pseudo Wigner–Ville) | 95.71 |

| Özkaya (2023) [17] | LEN-DB | 10,002 seismograms | MCLP | 96.82 |

| White (2023) [18] | STEAD | 65,536 seismograms | FastMap+SVM | 99.00 |

| Cui (2025) [10] | TXED | 20,000 seismograms | CNN + Multi-scale Attention | 99.83 |

| Ertuncay (2025) [19] | Italy | Earthquake, vehicle, noise | CNN | 99.81 |

| Indonesian ESM (2006–2009) [20] | 3 stations | 58 earthquake events | SVM, k-NN, DT | 92.00 |

| Habbak (2024) [21] | Egyptian National Seismic Network | 837 earthquake and quarry explosion | CNN | 100 |

| Vasti & Dev (2025) [22] | STEAD | 6000 earthquakes and noise | LSTM | 97.00 |

| Ertuncay (2024) [23] | Italy | 21,643 earthquakes and volcanic eruptions | DCNN | 99.00 |

| This study | LEN-DB | 300,000 seismograms | EMD+DWT/Lasso/RF | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erdoğan, Y.E.; Narin, A. Time-Frequency-Based Separation of Earthquake and Noise Signals on Real Seismic Data: EMD, DWT and Ensemble Classifier Approaches. Sensors 2025, 25, 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216671

Erdoğan YE, Narin A. Time-Frequency-Based Separation of Earthquake and Noise Signals on Real Seismic Data: EMD, DWT and Ensemble Classifier Approaches. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216671

Chicago/Turabian StyleErdoğan, Yunus Emre, and Ali Narin. 2025. "Time-Frequency-Based Separation of Earthquake and Noise Signals on Real Seismic Data: EMD, DWT and Ensemble Classifier Approaches" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216671

APA StyleErdoğan, Y. E., & Narin, A. (2025). Time-Frequency-Based Separation of Earthquake and Noise Signals on Real Seismic Data: EMD, DWT and Ensemble Classifier Approaches. Sensors, 25(21), 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216671