1. Introduction

WuShu Sanda is a high-intensity combat sport that combines kicking, striking, and throwing techniques, requiring athletes to respond quickly and execute precise movements in rapidly changing combat environments [

1]. Previous studies have shown that combat sports (such as boxing and taekwondo) can significantly improve an individual’s neural regulation abilities, including enhancing motor cortex excitability, optimizing sensory–motor integration, and improving reaction inhibition functions [

2,

3]. For example, athletes who have engaged in long-term combat training exhibit superior performance in limb coordination, dynamic balance, and decision-making speed compared to the general population, suggesting that such sports may have a unique shaping effect on the brain’s cognitive–motor control system [

4]. However, despite WuShu Sanda being a representative of traditional Chinese combat sports, quantitative research on its training effects in the field of neuroscience remains limited. Existing research has primarily focused on other martial arts disciplines, with limited empirical evidence on the neural mechanisms and cognitive–motor control effects of Sanda. Moreover, research on how the absence of Sanda combat experience influences the conflict adaptation effect is lacking, and the integration of ERP and HRV studies remains underexplored. Systematic exploration using objective physiological indicators (such as electroencephalography and heart rate variability) is urgently needed [

5,

6].

Cognitive–motor control refers to the brain’s higher-order regulatory capacity in integrating sensory information and motor execution processes, directly influencing an individual’s reaction speed, movement accuracy, and environmental adaptability [

7,

8]. Previous studies have found that this ability is not only a core element of competitive sports performance but is also closely related to motor learning, injury prevention, and rehabilitation in daily life [

9,

10]. For example, high-level athletes demonstrate superior cognitive flexibility and motor inhibition in conflict tasks, and motor interventions (such as aerobic training and coordination training) have been shown to enhance functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and motor cortex [

11,

12]. As a sport that combines high-intensity physical exertion with complex tactical decision-making, Wushu Sanda may optimize cognitive–motor control through dual pathways (neuroplasticity and autonomic nervous system regulation), but there is currently a lack of direct evidence on how Sanda training influences this system [

13,

14]. Therefore, investigating the effects of Sanda on cognitive–motor control not only fills a theoretical gap but also provides a scientific basis for optimizing exercise intervention programs.

While the physical and performance outcomes of Sanda training are well-documented, the underlying neurophysiological adaptations, particularly those pertaining to cognitive–motor control and autonomic regulation, remain largely unexplored. Existing research has primarily focused on external performance metrics, leaving the internal brain and heart dynamics as a “black box.” This study aims to address this gap by employing a multimodal EEG-ECG approach to pioneer a neuro-cardiac perspective on Sanda training.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 20 Sanda athletes and 20 ordinary college students were recruited through public recruitment, all of whom were right-handed males, aged between 18 and 29 years (M ± SD = 23.1 ± 2.4). The inclusion criteria for the Sanda group included having a first-class or higher athlete qualification, with continuous systematic training for ≥5 years, and an average weekly training of ≥10 h in the past 6 months; the control group had no regular exercise habits, and their BMI was matched with that of the Sanda group. Exclusion criteria included having color blindness/color weakness, a history of traumatic brain injury, the presence of mental or cardiovascular diseases, and taking drugs that affect heart rate or the central nervous system. In addition, participants were required not to engage in strenuous exercise and not to consume caffeine or alcohol within 24 h before the experiment. Finally, 1 participant was excluded from each group due to >25% EEG artifacts or >5% missing HRV signals, resulting in 19 valid samples in the Sanda group and 19 in the control group. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai University of Sport (approval number: 102772024RT018).

2.2. Research Design

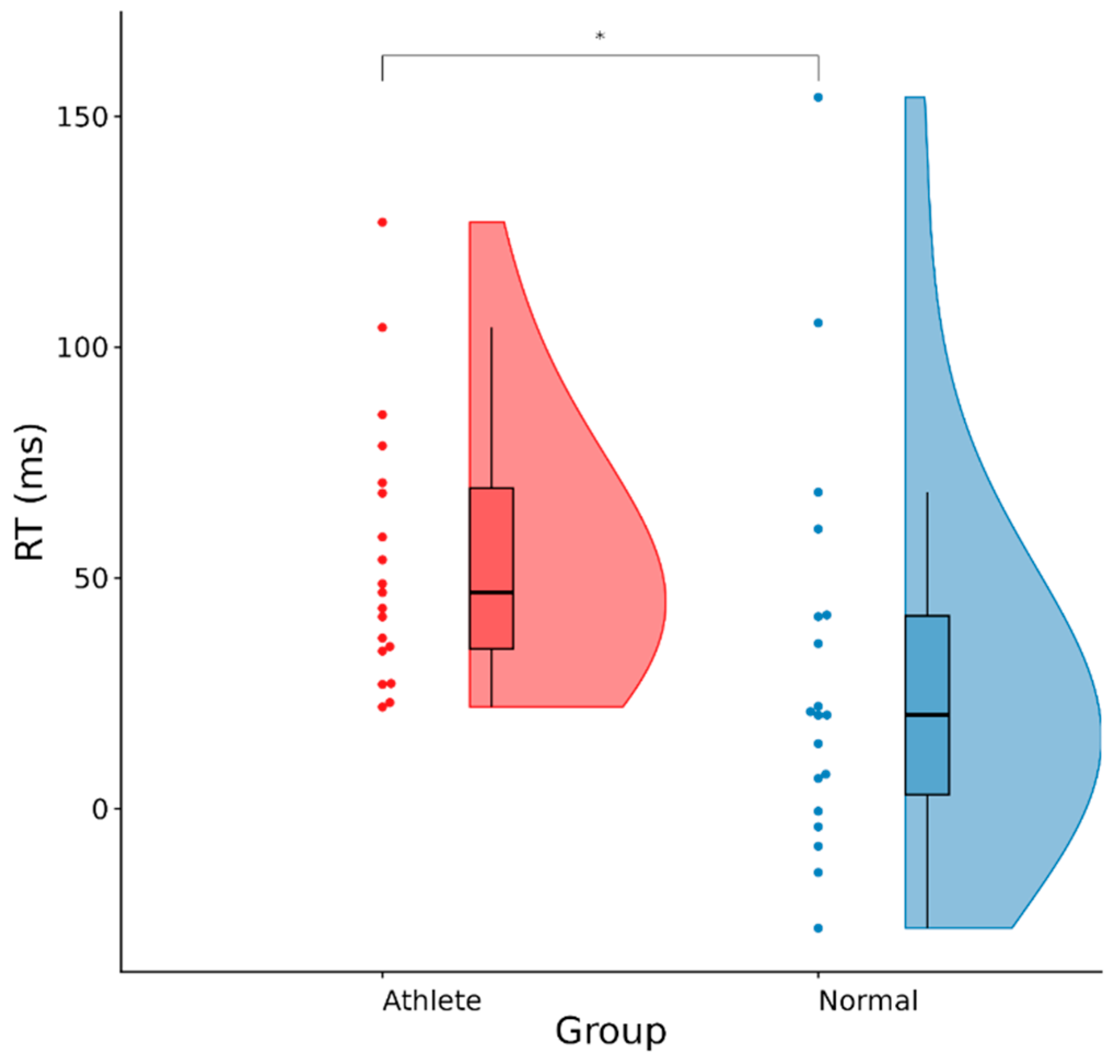

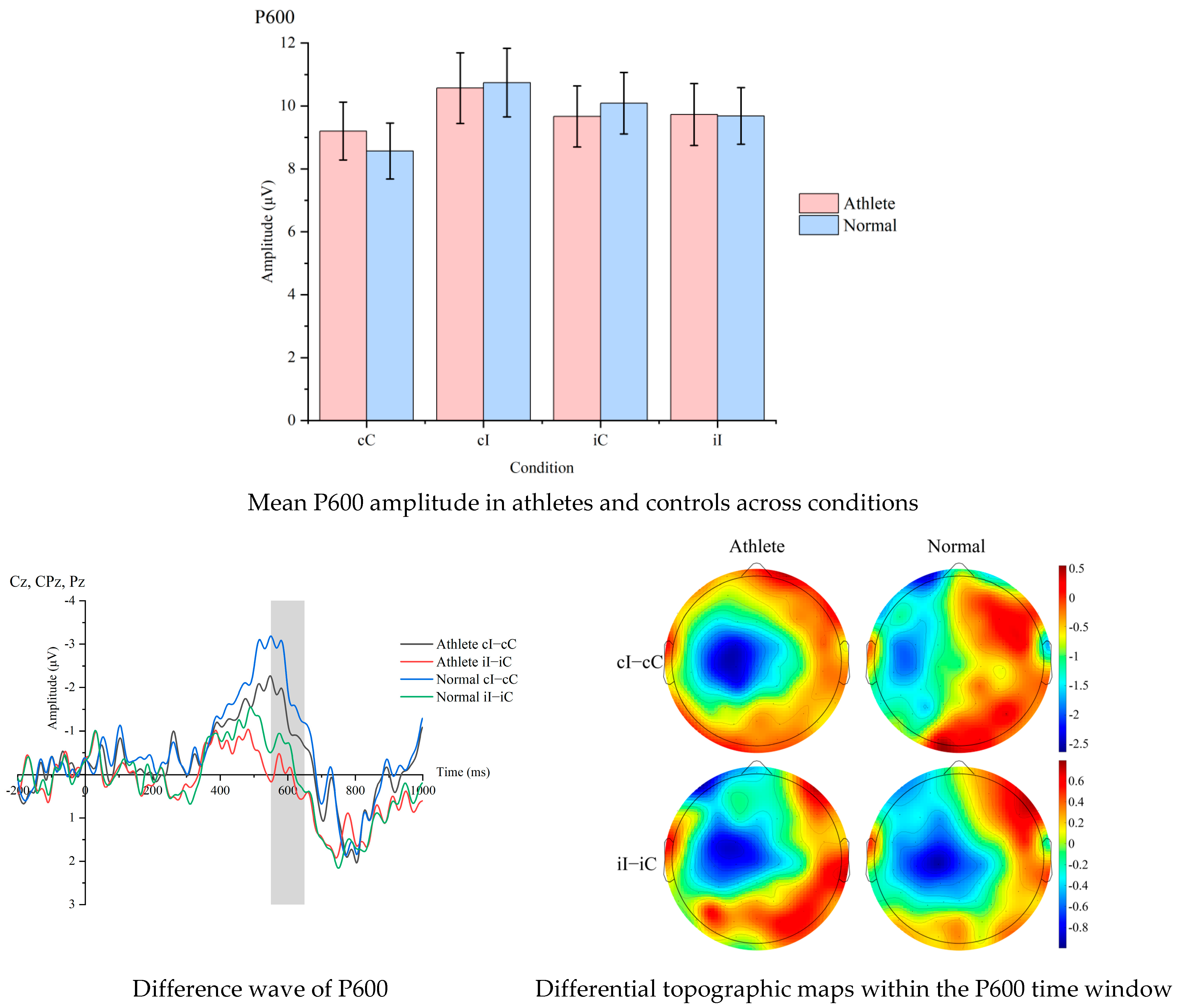

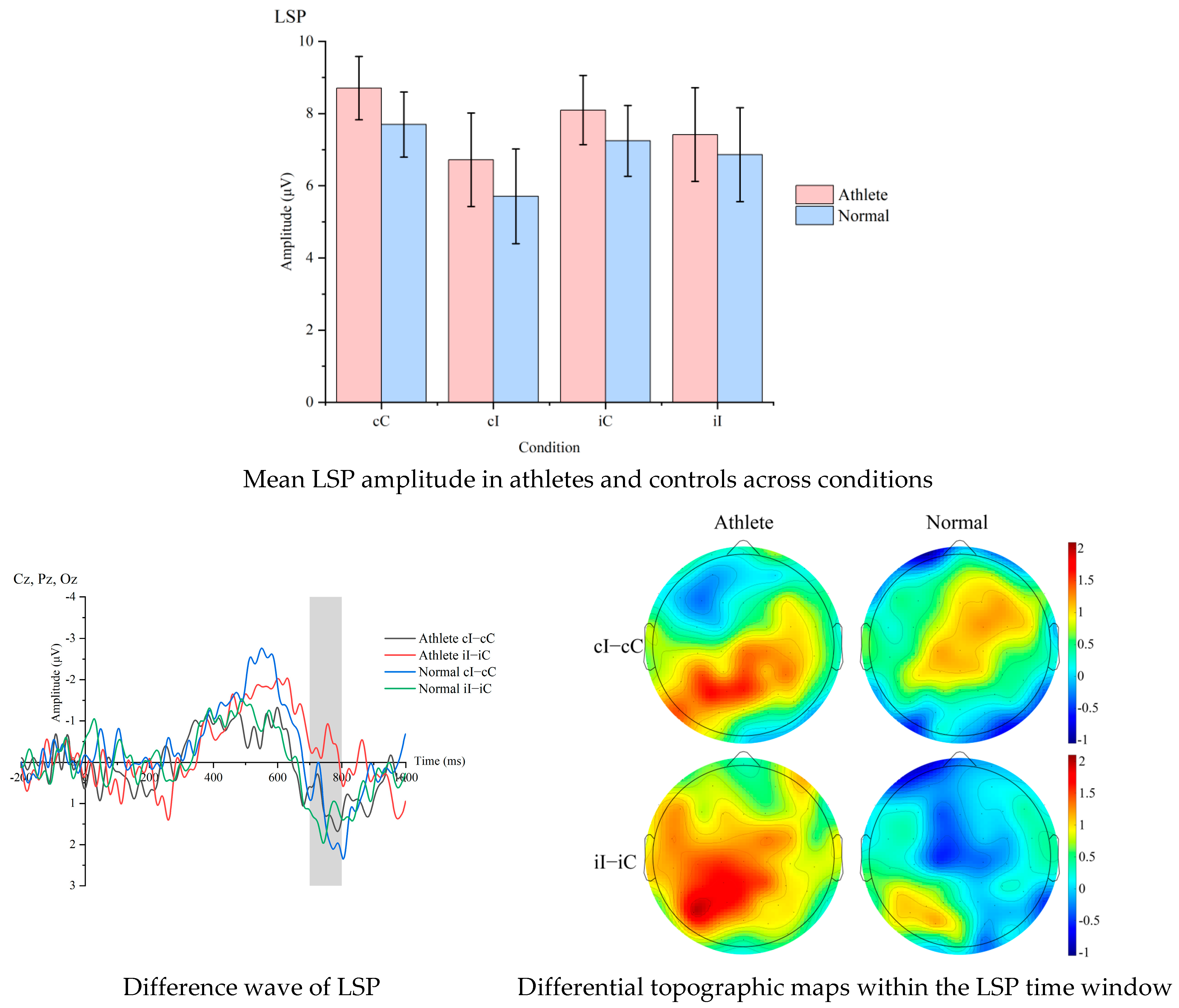

The experiment adopted a 2 (group: Sanda athletes vs. ordinary college students) × 2 (phase: pre-task rest vs. post-task rest) × 4 (Stroop conditions: cC, cI, iC, iI) three-factor mixed design. The between-group variable was the group, and the within-group variables were phase and Stroop conditions. The dependent variables included (1) behavioral indicators: reaction time, accuracy rate, and conflict adaptation effect [(cI − cC) − (iI − iC)], which measure the reduction in Stroop interference after incongruent trials compared to congruent trials; (2) ERP indicators: average amplitude and difference wave of P600 (550–650 ms) and LSP (700–800 ms); (3) HRV indicators: RMSSD, HF power (ms2).

2.3. Research Process

The entire experiment was conducted in a soundproof and constant-temperature (25 °C) electromagnetic shielding room, with strictly fixed timing to ensure environmental constancy and comparability of multimodal data. Upon arrival, participants first sat quietly in the rest area for 15 min to adapt to the environment, during which they completed personal information filling and informed consent signing. Subsequently, the experimenter assisted in wearing a 64-channel Ag/AgCl electrode cap (Greentek Pty. Ltd., Hubei, China, positioned according to the international 10–20 system, with grounding and reference at AFz and FCz, respectively) and attaching disposable Ag/AgCl ECG electrodes to form a standard three-lead ECG (RA-LL-LA). The recording equipment was a BrainAMP 64-channel amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany) and Brain Vision Recorder 2.0 software. The experimenter briefly explained the experimental process to ensure that participants understood the task requirements and reconfirmed that they had no strenuous exercise, caffeine, or alcohol intake within the last 24 h.

Then, the resting baseline phase began: the lights were dimmed, participants maintained a comfortable sitting posture, closed their eyes to relax but stayed awake, and continuously recorded ECG for 5 min, which served as the pre-task HRV indicator (Pre). Immediately after the baseline, the Stroop-ERP task started. This task adopted the classic color-word Stroop paradigm, consisting of 2 sequences, with 101 trials in each sequence, and the total duration was approximately 13 min. The stimulus materials were the four characters “red, yellow, blue, green”, each presented in four colors. Participants need to determine whether the color of the word is congruent with its meaning. The congruent and incongruent trials each accounted for 50% and were pseudo-randomly arranged to ensure 25 trials for each of the Stroop conditions: cC, cI, iC, and iI. The trial process was as follows: Central fixation point “+” presented for 1000 ms → random blank screen for 300–1000 ms → color-word stimulus for 800 ms → blank screen for 1700 ms. Participants needed to press the “1” key with their right index finger to indicate that the font color was consistent with the word meaning, and the middle finger to press the “2” key to indicate inconsistency. Responses were allowed at any time during the stimulus or blank screen; there was no additional feedback after pressing the key, and the system automatically recorded the key presses and reaction times. Participants were allowed to rest for 30 s between the two sequences, and the experimenter reconfirmed that there was no electrode impedance drift before starting the next sequence.

Immediately after the task was completed, the recovery phase began: the lights were dimmed again, participants maintained the same closed-eye sitting posture as in the baseline phase, and 5 min of ECG was continuously collected as the post-task HRV indicator (Post). Throughout the experiment, TTL synchronization pulses were automatically sent by E-Prime 3.0 to the EEG and ECG acquisition systems at the start and end of each phase, ensuring a time accuracy of <1 ms for cross-modal data to achieve precise coupling of ERP and HRV. After the recovery recording was completed, the experimenter turned off the acquisition system, assisted participants in removing the electrodes and ECG patches, cleaned the skin with alcohol pads, and the entire experiment ended.

2.4. Measurement Indicators

This study constructed a measurement system based on three main lines: behavioral performance, neuroelectrophysiology, and cardiac autonomic nervous activity. All indicators followed the collection, processing, and reporting standards jointly recommended by the Society for Psychophysiological Research (SPR) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and ensured the comparability and coupling accuracy of cross-modal data through timestamp synchronization and quality control procedures throughout the experiment.

2.4.1. Behavioral

At the behavioral level, the classic color-word Stroop paradigm was used to record the key-press responses of participants under four sequence conditions (cC, cI, iC, iI) with millisecond precision. Reaction time (RT) was defined as the time interval from the appearance of the stimulus to the correct key press. For each participant, error trials and extreme values (less than 300 ms or greater than the individual mean ± 3 standard deviations) were first excluded, and then the arithmetic mean under each condition was calculated; the accuracy rate (ACC) was the percentage of correct key presses in the valid trials under that condition. To reduce the impact of non-normal distribution, all percentages were transformed using the arcsine square root before entering the subsequent statistical model. The conflict adaptation effect (CAE) was calculated by the formula [(cI − cC) − (iI − iC)], where the values in the brackets were reaction time differences. A larger value of this indicator indicated that an individual had a stronger ability to inhibit and adjust subsequent conflicts after experiencing a conflict.

2.4.2. ERP

At the neuroelectrophysiological level, event-related potential (ERP) data were continuously recorded with a 64-channel Ag/AgCl electrode cap at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. Offline processing used the EEGLAB/ERPLAB toolchain, including referencing to bilateral mastoids, 0.1–30 Hz zero-phase Butterworth filtering, ICA to remove eye movement and electromyographic artifacts, ±100 μV artifact rejection, segmentation from −200 ms to 1000 ms, and baseline correction from −200 ms to 0 ms. Based on the previous literature and scalp topographic map verification, two-time windows of P600 (550–650 ms) and LSP (700–800 ms) were selected to represent the conflict reanalysis and conflict resolution stages, respectively, with electrode sites at Cz, CPz, Pz and Cz, Pz, Oz, respectively, and the average amplitude (μV) of each participant under each condition was calculated. Prior studies have shown that LSP is often distributed over parietal–occipital/posterior regions during conflict task [

15]. P600 has a strong correlation with cognitive control; during stimulus presentation, incongruent trials tend to show greater amplitude compared to congruent trials, reflecting a close relationship with the cognitive control adjustment process [

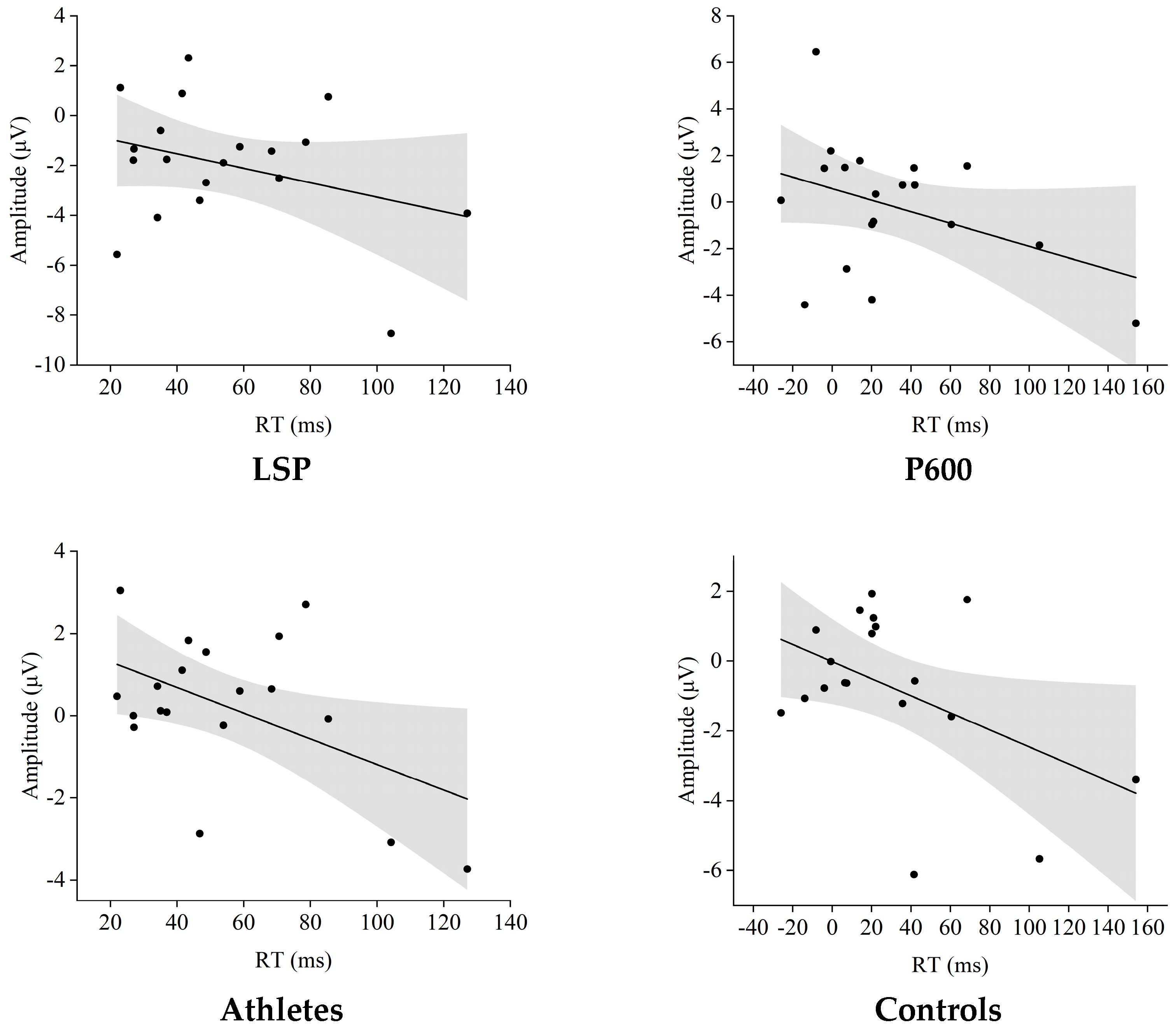

16]. To highlight cognitive control processing, difference waves (incongruent minus congruent) and conflict adaptation ERP indicators, i.e., [(cI − cC) − (iI − iC)], were further generated for cross-level coupling analysis with behavioral CAE. In terms of signal quality, only participants with a proportion of valid trials ≥ 80% after artifact rejection was retained, and the retention rates of the two groups showed no significant difference by independent sample t-test, ensuring comparability between groups.

2.4.3. HRV

At the cardiac autonomic nervous level, standard three-lead ECG (RA-LL-LA) was recorded synchronously at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz with a hardware bandpass of 0.5–150 Hz. R-peak identification was completed by the Kubios Premium 3.5 automatic algorithm, and abnormal beats were checked manually segment by segment and interpolated, with the proportion of abnormal beats controlled within 5%. The time-domain indicator RMSSD (ms) was calculated as the square root of the sum of the squares of adjacent R-R interval differences, reflecting parasympathetic tone; the frequency-domain indicator HF power (ms2) was estimated in the 0.15–0.40 Hz frequency band using the Welch periodogram method (256-point Hamming window, 50% overlap), representing pure parasympathetic activity. To control the potential contamination of HF by respiration, participants were prompted to maintain a natural breathing rhythm throughout the experiment, and the Kubios built-in respiratory filter was enabled during the analysis phase for correction. Finally, the differences ΔRMSSD and ΔHF between post- and pre-task were used as individual post-stress recovery indices, with higher values indicating more rapid autonomic nervous recovery. The effective sinus beat sequences in all HRV periods must be >95%; if atrial or ventricular premature beats occurred, the entire segment was excluded and re-collected to ensure data integrity.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All tests in this study were completed in SPSS 26.0, with a unified significance level set to two-tailed α = 0.05, Bonferroni–Holm correction for post hoc multiple comparisons, and partial η2 (ηp2) for effect size reporting. Firstly, for behavioral and ERP data, a 2 (group: Sanda athletes vs. ordinary college students) × 4 (Stroop conditions: cC, cI, iC, iI) mixed-design repeated measures variance model was established; if Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated a violation of the assumption (p < 0.05), the degrees of freedom and p-values corrected by Greenhouse–Geisser were reported. At the behavioral level, the conflict adaptation effect value [(cI − cC) − (iI − iC)] was used as the dependent variable, and at the ERP level, the differential amplitudes of P600 and LSP [(cI − cC) − (iI − iC)] were used as the dependent variables. The same 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA was performed, respectively, to confirm the main effect and interaction effect of the group in the conflict monitoring and conflict resolution stages. Secondly, for HRV recovery indicators, a 2 (group) × 2 (phase: pre-task rest vs. post-task rest) mixed ANOVA was used, with ΔRMSSD and ΔHF as dependent variables, to investigate whether autonomic nervous recovery varies with exercise experience. Thirdly, to explore the neuro-cardiac coupling mechanism, Pearson product–moment correlations between ΔRMSSD, ΔHF, and behavioral conflict adaptation effect, as well as P600 and LSP differential amplitudes, were calculated within each group. To examine whether autonomic recovery mediated the relationship between Sanda experience and cognitive–motor control, a simple mediation model was tested with PROCESS macro (Model 4). Group (Sanda athletes coded 1, controls coded 0) served as the independent variable X; the post-minus-pre change in RMSSD (ΔRMSSD) served as the mediator M; and the behavioral conflict adaptation effect (CAE in ms) served as the dependent variable Y. Age and BMI were entered as covariates. Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) were computed based on 5000 resamples; a CI that did not straddle zero indicated a significant indirect effect.