Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants

Abstract

1. Introduction

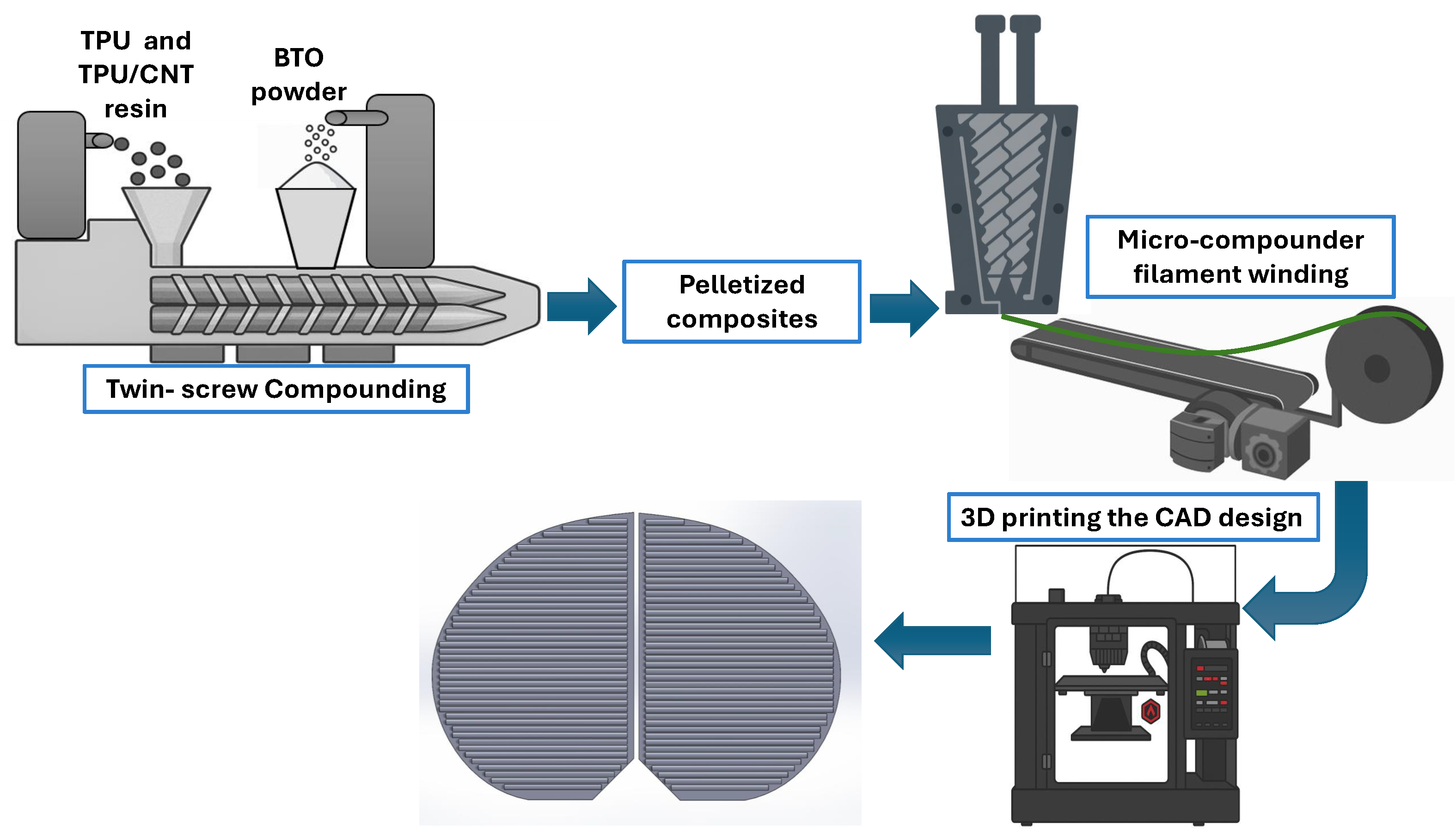

2. Materials and Fabrication

2.1. Materials

2.2. Compounding and Filament Fabrication

2.3. Three-Dimensional Printing

3. Harvester Package and the Working Principle

4. Experimental Setup

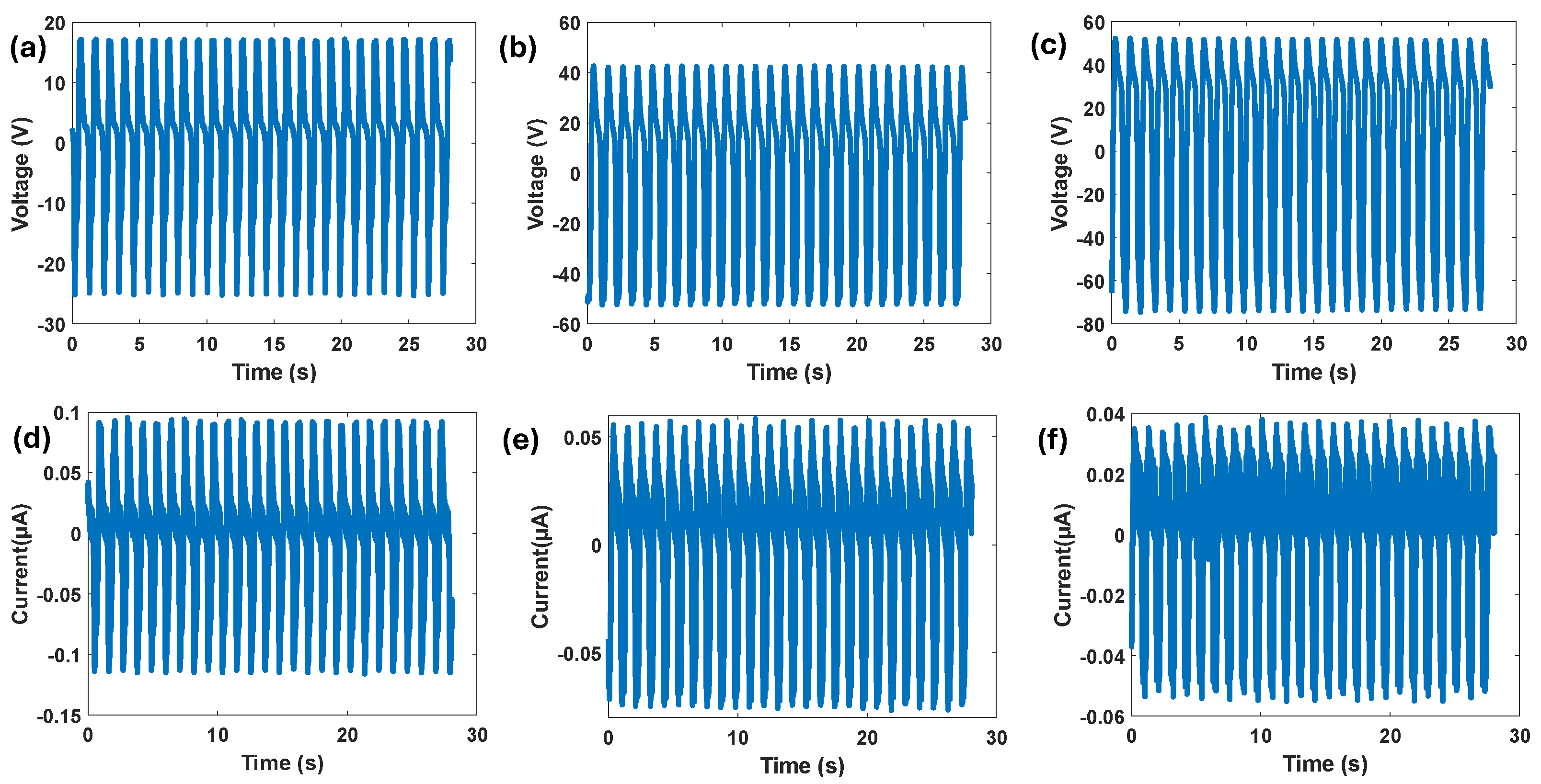

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeFrance, M.J.; Scuderi, G.R. Are 20% of patients actually dissatisfied following total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Lima, D.D.; Fregly, B.J.; Patil, S.; Steklov, N.; Colwell, C.W., Jr. Knee joint forces: Prediction, measurement, and significance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2012, 226, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.A.; Yu, S.; Chen, L.; Cleveland, J.D. Rates of total joint replacement in the United States: Future projections to 2020–2040 using the national inpatient sample. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 46, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.T.; Walker, R.W.; Evans, J.P.; Blom, A.W.; Sayers, A.; Whitehouse, M.R. How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet 2019, 393, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichman, I.; Roof, M.; Askew, N.; Nherera, L.; Rozell, J.C.; Seyler, T.M.; Schwarzkopf, R. Projections and epidemiology of primary hip and knee arthroplasty in medicare patients to 2040–2060. JBJS Open Access 2023, 8, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margo, B.J.; Radnay, C.S.; Scuderi, G.R. Anatomy of the knee. In The Knee: A Comprehensive Review; World Scientific Publishing: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Masouros, S.; Bull, A.; Amis, A. (i) Biomechanics of the knee joint. Orthop. Trauma 2010, 24, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayfur, A.; Tayfur, B. The Knee. In Functional Exercise Anatomy and Physiology for Physiotherapists; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Affatato, S. Biomechanics of the knee. In Surgical Techniques in Total Knee Arthroplasty and Alternative Procedures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wylde, V.; Dieppe, P.; Hewlett, S.; Learmonth, I. Total knee replacement: Is it really an effective procedure for all? Knee 2007, 14, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.J.; Alvand, A.; Troelsen, A.; Katz, J.N.; Hooper, G.; Gray, A.; Carr, A.; Beard, D. Knee replacement. Lancet 2018, 392, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, N.; Shoman, H.; Olavarria, F.; Matsumoto, T.; Kuroda, R.; Khanduja, V. Why are patients dissatisfied following a total knee replacement? A systematic review. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 1971–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Walker, P.; Perry, J.; Cannon, S.; Woledge, R. The forces in the distal femur and the knee during walking and other activities measured by telemetry. J. Arthroplast. 1998, 13, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-alla, A.e.n.; Asker, N. Numerical simulations for the phase velocities and the electromechanical coupling factor of the Bleustein–Gulyaev waves in some piezoelectric smart materials. Math. Mech. Solids 2016, 21, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ni, S.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Chu, H.Y.; Zhang, N.; Sun, M.; Li, N.; Ren, Q.; et al. Targeting loop3 of sclerostin preserves its cardiovascular protective action and promotes bone formation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, D.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Barshilia, H.C. A state-of-the-art review on the multifunctional self-cleaning nanostructured coatings for PV panels, CSP mirrors and related solar devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Z.A.; Jeon, J.W.; Jang, S.Y. Intrinsically self-healable, stretchable thermoelectric materials with a large ionic Seebeck effect. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochniak, A.; Hadasz, L.; Ruba, B. Dynamical generalization of Yetter’s model based on a crossed module of discrete groups. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, S.R.; Farritor, S.; Garvin, K.; Haider, H. The use of piezoelectric ceramics for electric power generation within orthopedic implants. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2005, 10, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Olawumi, M.A.; Olugbade, T.O. Innovative Orthopedic Solutions for AI-Optimized Piezoelectric Implants for Superior Patient Care. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.R.; Tian, Z.Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potu, S.; Kulandaivel, A.; Gollapelli, B.; Khanapuram, U.K.; Rajaboina, R.K. Oxide based triboelectric nanogenerators: Recent advances and future prospects in energy harvesting. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2024, 161, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, K.H.; Lin, L.; Chung, C.K. Low-cost micro-graphite doped polydimethylsiloxane composite film for enhancement of mechanical-to-electrical energy conversion with aluminum and its application. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 135, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as flexible power sources. Npj Flex. Electron. 2017, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, K.N.; Park, S.I.; Qazi, R.; Zou, Z.; Mickle, A.D.; Grajales-Reyes, J.G.; Jang, K.I.; Gereau IV, R.W.; Xiao, J.; Rogers, J.A.; et al. Miniaturized, battery-free optofluidic systems with potential for wireless pharmacology and optogenetics. Small 2018, 14, 1702479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ahn, D.; Kim, J.; Ahn, S.; Hwang, J.S.; Kwon, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, J.M.; Nam, K.; Park, J.J. Surface-control enhanced crater-like electrode in a gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol/carbon composite for biodegradable multi-modal sensing systems with human-affinity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 9145–9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ren, T.; Li, H.; Chen, B.; Mao, Y. Recent progress of nature materials based triboelectric nanogenerators for electronic skins and human–machine interaction. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2300245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, H. 3D printing individualized triboelectric nanogenerator with macro-pattern. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theory of sliding-mode triboelectric nanogenerators. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6184–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Bahadur, J.; Panwar, V.; Singh, P.; Rathi, K.; Pal, K. Effective energy harvesting from a single electrode based triboelectric nanogenerator. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hassan, I.; Helal, A.S.; Sencadas, V.; Radhi, A.; Jeong, C.K.; El-Kady, M.F. Triboelectric nanogenerator versus piezoelectric generator at low frequency (<4 Hz): A quantitative comparison. iScience 2020, 23, 101286. [Google Scholar]

- Manchi, P.; Graham, S.A.; Dudem, B.; Patnam, H.; Yu, J.S. Improved performance of nanogenerator via synergetic piezo/triboelectric effects of lithium niobate microparticles embedded composite films. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 201, 108540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.J.; Sohn, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Park, I.K. Polymer Composite-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerators: Recent Progress, Design Principles, and Future Perspectives. Polymers 2025, 17, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Bai, Y.; Shao, J.; Meng, H.; Li, Z. Strategies to improve the output performance of triboelectric nanogenerators. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, Z.; Shen, F.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Guo, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Progress in techniques for improving the output performance of triboelectric nanogenerators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 885–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Jain, M.; Salman, E.; Willing, R.; Towfighian, S. A smart knee implant using triboelectric energy harvesters. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 025040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahari, M.; Salman, E.; Stanacevic, M.; Willing, R.; Towfighian, S. Hybrid triboelectric-piezoelectric nanogenerator for long-term load monitoring in total knee replacements. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 055034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Bai, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.L. Ultrathin, rollable, paper-based triboelectric nanogenerator for acoustic energy harvesting and self-powered sound recording. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4236–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, R.; Xuan, W.; Chen, J.; Dong, S.; Jin, H.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Luo, J. Fully biodegradable triboelectric nanogenerators based on electrospun polylactic acid and nanostructured gelatin films. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.I.; Lee, M.; Liu, Y.; Moon, S.; Hwang, G.T.; Zhu, G.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, D.K.; Wang, Z.L.; et al. Flexible nanocomposite generator made of BaTiO3 nanoparticles and graphitic carbons. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2999–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajahat, M.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Khoo, S.Y.; Mahmud, M.P. A review on extrusion-based 3D-printed nanogenerators for energy harvesting. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 140–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tang, W.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Xu, L.; Guo, H.; Lin, P.; Li, D.; et al. Three-dimensional ultraflexible triboelectric nanogenerator made by 3D printing. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Meng, B.; Zhang, H. Investigation of power generation based on stacked triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, O.; Chahari, M.; Azami, M.; Ameli, A.; Salman, E.; Stanacevic, M.; Willing, R.; Towfighian, S. 3D printed CNT/TPU triboelectric nanogenerator for load monitoring of total knee replacement. Smart Mater. Struct. 2025, 34, 065030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, M.; Zhu, K.; Su, Z.; Cheng, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H. High performance triboelectric nanogenerators with aligned carbon nanotubes. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 18489–18494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, G.; Javed, M.S.; Wang, X.; Hu, C. Aligning graphene sheets in PDMS for improving output performance of triboelectric nanogenerator. Carbon 2017, 111, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.S.; Rahman, M.T.; Salauddin, M.; Sharma, S.; Maharjan, P.; Bhatta, T.; Cho, H.; Park, C.; Park, J.Y. Electrospun PVDF-TrFE/MXene nanofiber mat-based triboelectric nanogenerator for smart home appliances. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 4955–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghvami-Panah, M.; Azami, M.; Kalia, K.; Ameli, A. In situ foam 3D printed microcellular multifunctional nanocomposites of thermoplastic polyurethane and carbon nanotube. Carbon 2024, 230, 119619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, M.; Perivoliotis, D.K.; Bianchi, M.G.; Chiu, M.; Pagliaro, A.; Koklioti, M.A.; Trompeta, A.F.A.; Bergamaschi, E.; Bussolati, O.; Charitidis, C.A. Toxicity determinants of multi-walled carbon nanotubes: The relationship between functionalization and agglomeration. Toxicol. Rep. 2016, 3, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Cellular toxicity and immunological effects of carbon-based nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.C.; Barua, S.; Sharma, G.; Dey, S.K.; Rege, K. Inorganic nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. J. Control. Release 2011, 155, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, L.R.M.; Andrade, L.N.; Bahú, J.O.; Concha, V.O.C.; Machado, A.T.; Pires, D.S.; Santos, R.; Cardoso, T.F.; Cardoso, J.C.; Albuquerque-Junior, R.L.; et al. Biomedical applications of carbon nanotubes: A systematic review of data and clinical trials. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 99, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, D.; Patnaik, S.; Sood, S.; Das, N. Carbon nanotubes: Evaluation of toxicity at biointerfaces. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghimaa, M.; Sagadevan, S.; Boojhana, E.; Fatimah, I.; Lett, J.A.; Moharana, S.; Garg, S.; Al-Anber, M.A. Enhancing biocompatibility and functionality: Carbon nanotube-polymer nanocomposites for improved biomedical applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 99, 105958. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Qu, J.; Daoud, W.A.; Wang, L.; Qi, T. Flexible composite-nanofiber based piezo-triboelectric nanogenerators for wearable electronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 13347–13355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongampai, S.; Charoonsuk, T.; Pinpru, N.; Pulphol, P.; Vittayakorn, W.; Pakawanit, P.; Vittayakorn, N. Triboelectric-piezoelectric hybrid nanogenerator based on BaTiO3-Nanorods/Chitosan enhanced output performance with self-charge-pumping system. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 208, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Abdullah, A.M.; Hussain, I.; Lopez, J.; Cantu, D.; Gupta, S.K.; Mao, Y.; Danti, S.; Uddin, M.J. Lithium doped zinc oxide based flexible piezoelectric-triboelectric hybrid nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2019, 61, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Shi, Q.; He, T.; Yi, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, T.; Lee, C. Self-powered and self-functional cotton sock using piezoelectric and triboelectric hybrid mechanism for healthcare and sports monitoring. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 1940–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Shin, Y.E.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.P.; Kim, Y.R.; Na, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Ko, H. Ferroelectric multilayer nanocomposites with polarization and stress concentration structures for enhanced triboelectric performances. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7101–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorov, E.; Bárcenas, G.L.; Sánchez, B.L.E.; Franco, B.; Padilla-Vaca, F.; Landaverde, M.A.H.; Limón, J.M.Y.; López, R.A. Chitosan-BaTiO3 nanostructured piezopolymer for tissue engineering. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2020, 196, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, C. Triboelectric properties of BaTiO3/polyimide nanocomposite film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 572, 151391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, F.F.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Ambri Mohamed, M. Enhanced-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on polydimethylsiloxane/barium titanate/graphene quantum dot nanocomposites for energy harvesting. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5608–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, N.; Ajay Kumar, P.V.; Mohapatra, A.; Alex, Y.; Mohanty, S. Significant Role of Carbon Nanomaterials in Material Extrusion-Based 3D-Printed Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2201275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, H.J.; Ngai, V.; Wimmer, M.A. Comparison of ISO Standard and TKR patient axial force profiles during the stance phase of gait. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2012, 226, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Lima, D.D.; Fregly, B.J.; Colwell Jr, C.W. Implantable sensor technology: Measuring bone and joint biomechanics of daily life in vivo. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Deng, H.; Shi, S.; Tian, S.; Wu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zha, J.W.; et al. Advanced dielectric materials for triboelectric nanogenerators: Principles, methods, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2314380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Ye, B.U.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, D.; Kang, C.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Wang, Z.L.; Baik, J.M. Boosted output performance of triboelectric nanogenerator via electric double layer effect. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, G.; Bender, A.; Graichen, F.; Dymke, J.; Rohlmann, A.; Trepczynski, A.; Heller, M.O.; Kutzner, I. Standardized loads acting in knee implants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Hossain, N.A.; Towfighian, S.; Willing, R.; Stanaćević, M.; Salman, E. Self-powered load sensing circuitry for total knee replacement. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 22967–22975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdalla, O.; Azami, M.; Ameli, A.; Salman, E.; Stanacevic, M.; Willing, R.; Towfighian, S. Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants. Sensors 2025, 25, 6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206454

Abdalla O, Azami M, Ameli A, Salman E, Stanacevic M, Willing R, Towfighian S. Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants. Sensors. 2025; 25(20):6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206454

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdalla, Osama, Milad Azami, Amir Ameli, Emre Salman, Milutin Stanacevic, Ryan Willing, and Shahrzad Towfighian. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants" Sensors 25, no. 20: 6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206454

APA StyleAbdalla, O., Azami, M., Ameli, A., Salman, E., Stanacevic, M., Willing, R., & Towfighian, S. (2025). Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants. Sensors, 25(20), 6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206454