Evaluation of Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Considering Node Mobility and Multiple Failure Modes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Comprehensively considering four types of failure modes: hardware/software failure, energy consumption failure, intentional attack, and isolation failure, we model the nodes in VANETs, thereby expanding the versatility of the node failure model;

- Design a cluster application scenario for VANETs, considering factors such as the overall network objectives, the influence relationships between nodes, the movement trends of the network and nodes, and periodic information transmission;

- Design a simulation algorithm and metrics for solving the connectivity reliability of VANETs, and further investigate the impact of attraction distance between nodes on node failure and network connectivity reliability in cluster application scenarios of VANETs through sensitivity analysis.

2. Related Work

2.1. Research on the Reliability of Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks

2.2. Research on the Reliability of Similar Self-Organizing Networks

3. Analysis and Modeling of Node Hardware/Software Failure

4. Analysis and Modeling of Node Energy Consumption Failure

4.1. Node Energy Consumption Model

4.2. Analysis of the Amount of Information Processed by Nodes

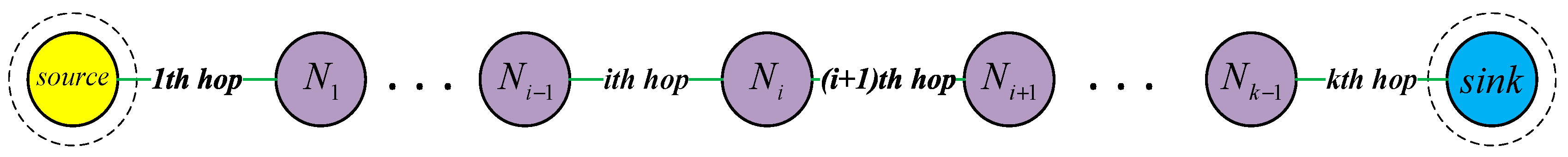

4.3. Routing Path Recognition Algorithm

| Algorithm 1. ITS1 routing path identification algorithm. | |

| Input: | Source node ; Sink node set ; Node coordinates ; communication distance threshold |

| Output: | Complete routing path set |

| 1. | calculate |

| 2. | generate |

| 3. | // Generate link information |

| 4. | classify , , |

| 5. | set |

| 6. | set |

| 7. | // Initialize node sets |

| 8. | While |

| 9. | // Find paths from to |

| 10. | For |

| 11. | find |

| 12. | extract |

| 13. | update |

| 14. | update |

| 15. | update |

| 16. | End For |

| 17. | re-determine |

| 18. | End While |

| 19. | Output |

| Algorithm 2. ITS2 routing path identification algorithm. | |

| Input: | Source node set ; Sink node ; Node coordinates ; communication distance threshold |

| Output: | Complete routing path set |

| 1. | calculate |

| 2. | generate |

| 3. | // Generate link information |

| 4. | For : |

| 5. | // Find paths from to |

| 6. | find |

| 7. | update |

| 8. | End For |

| 9. | Output |

| Algorithm 3. ITS3 routing path identification algorithm. | |

| Input: | Source node set ; Sink node ; Node coordinates ; communication distance threshold |

| Output: | Complete routing path set |

| 1. | calculate |

| 2. | generate |

| 3. | // Generate link information |

| 4. | classify , , |

| 5. | set |

| 6. | set |

| 7. | // Initialize node sets |

| 8. | While |

| 9. | // Find paths from to |

| 10. | For |

| 11. | find |

| 12. | extract |

| 13. | update |

| 14. | update |

| 15. | update |

| 16. | End For |

| 17. | re-determine |

| 18. | End While |

| 19. | Output |

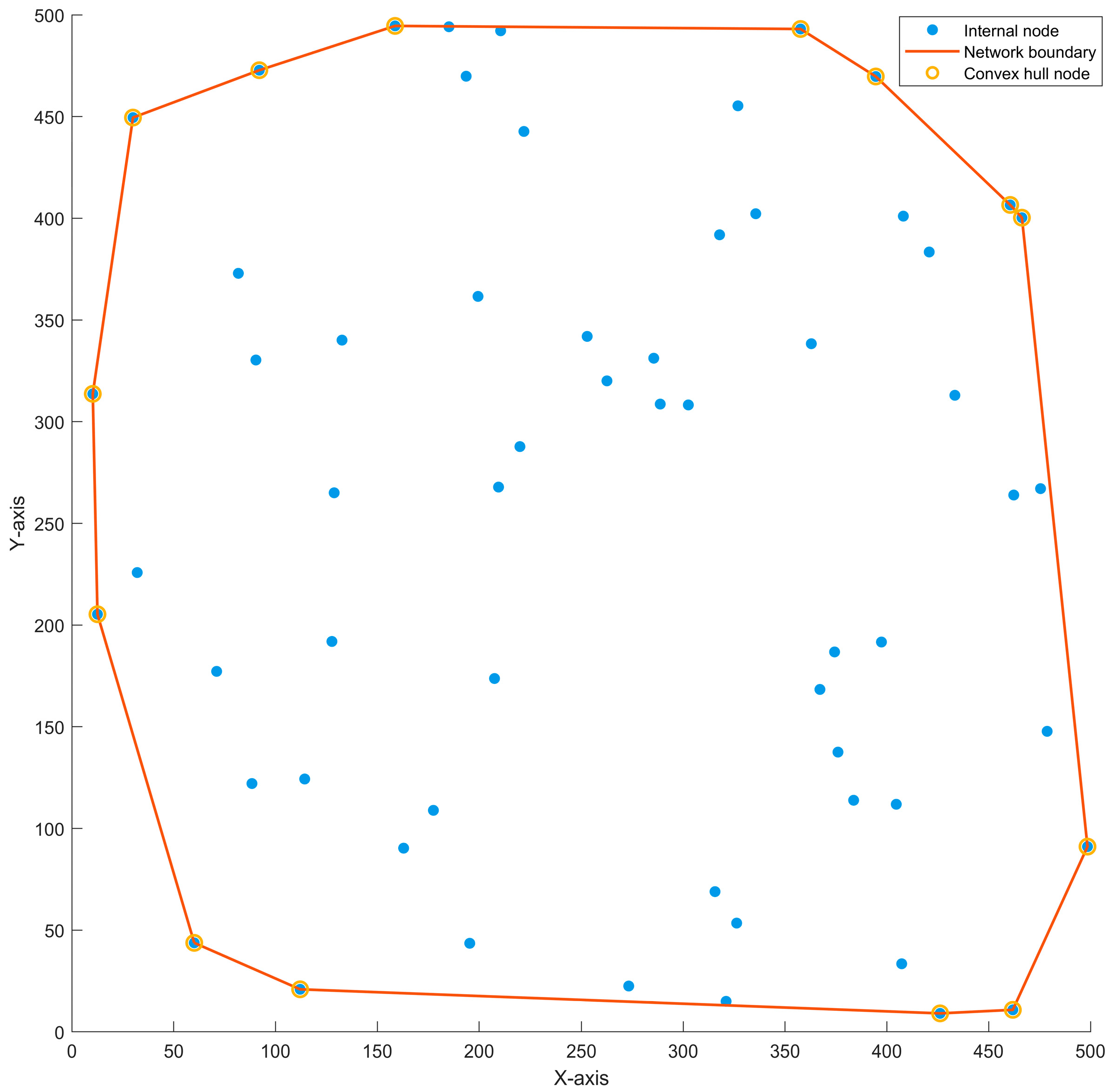

5. Node Mobility Analysis and Communication Link Modeling

5.1. Node Position Update Equation

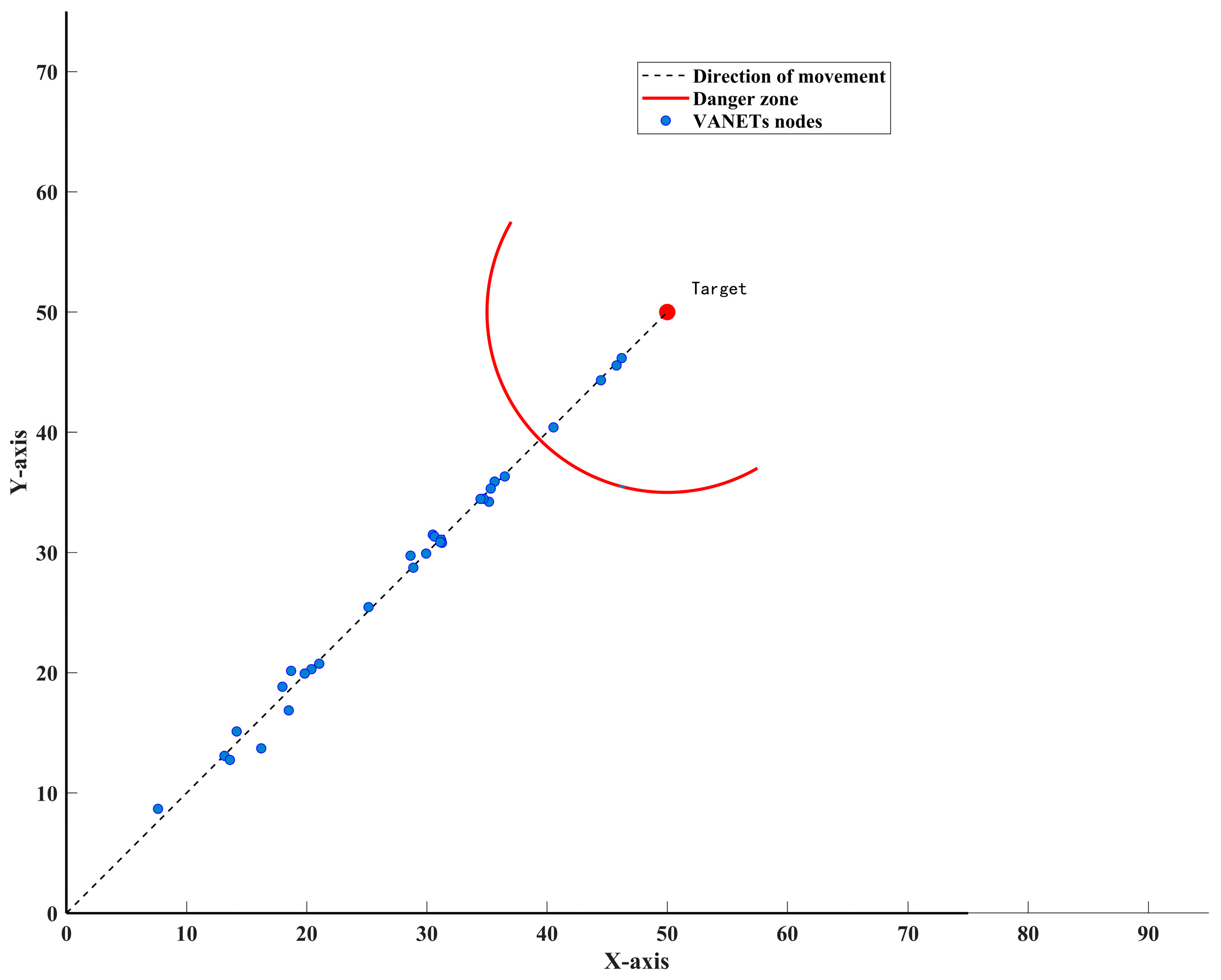

5.2. Couzin-Leader Improved Model

5.3. VANETs Node Location Update Algorithm Based on the Improved Couzin-Leader Model

5.4. Node Communication Link Modeling

6. Analysis and Modeling of Intentional Attack

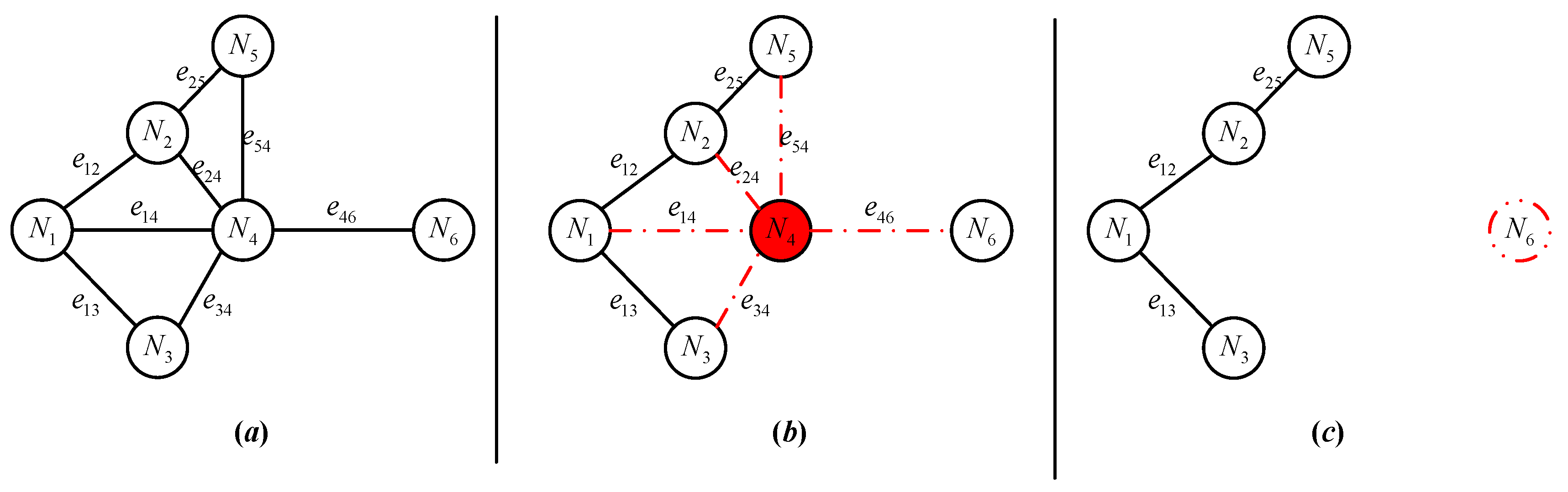

7. Analysis and Modeling of Node Isolation Failure

8. Connectivity Reliability Evaluation Algorithm

8.1. Connectivity Reliability Metrics Definition

8.2. Simulation Algorithm for Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Based on Node Motion Characteristics

9. Case Study

9.1. Simulation Case Parameter Setting

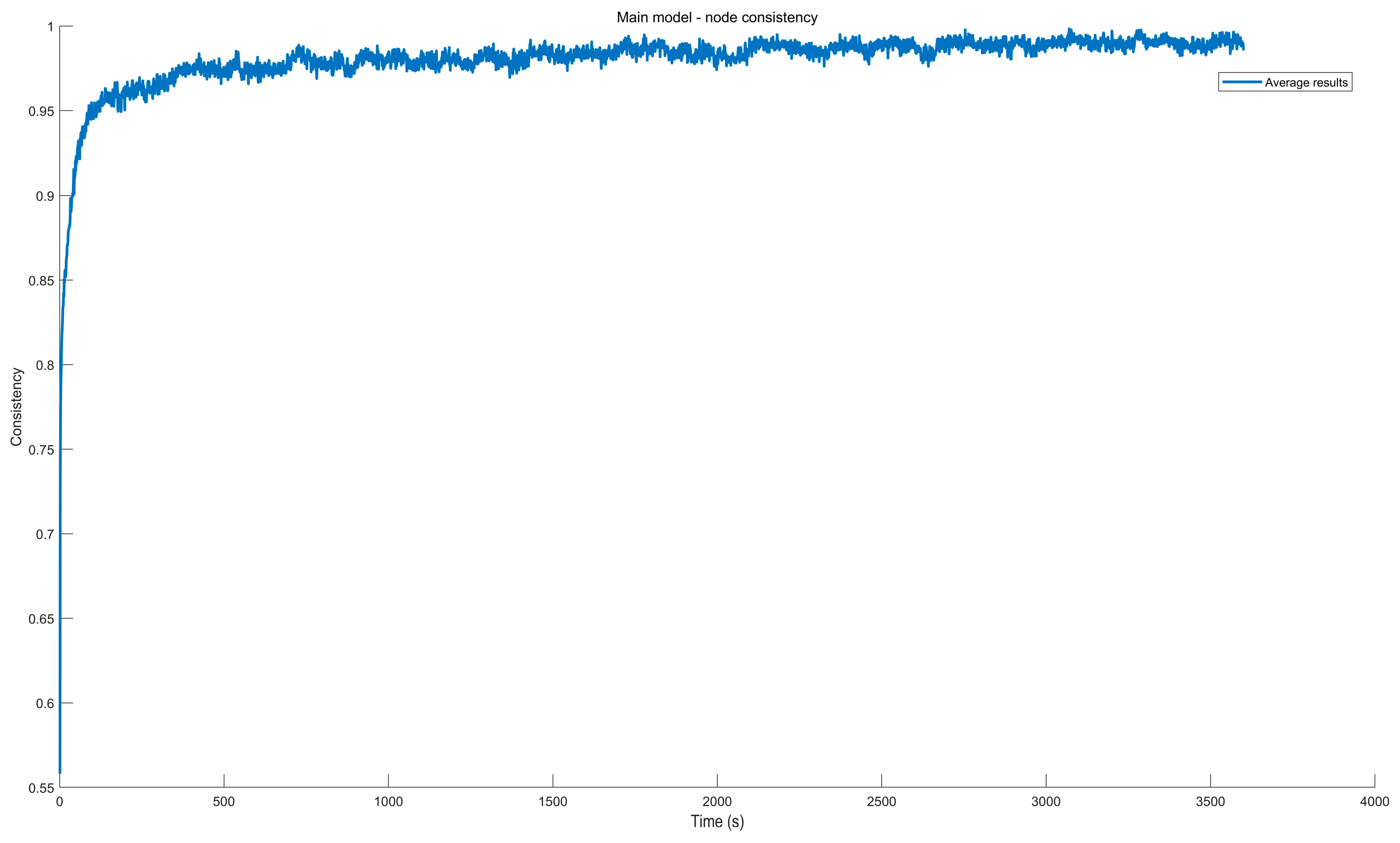

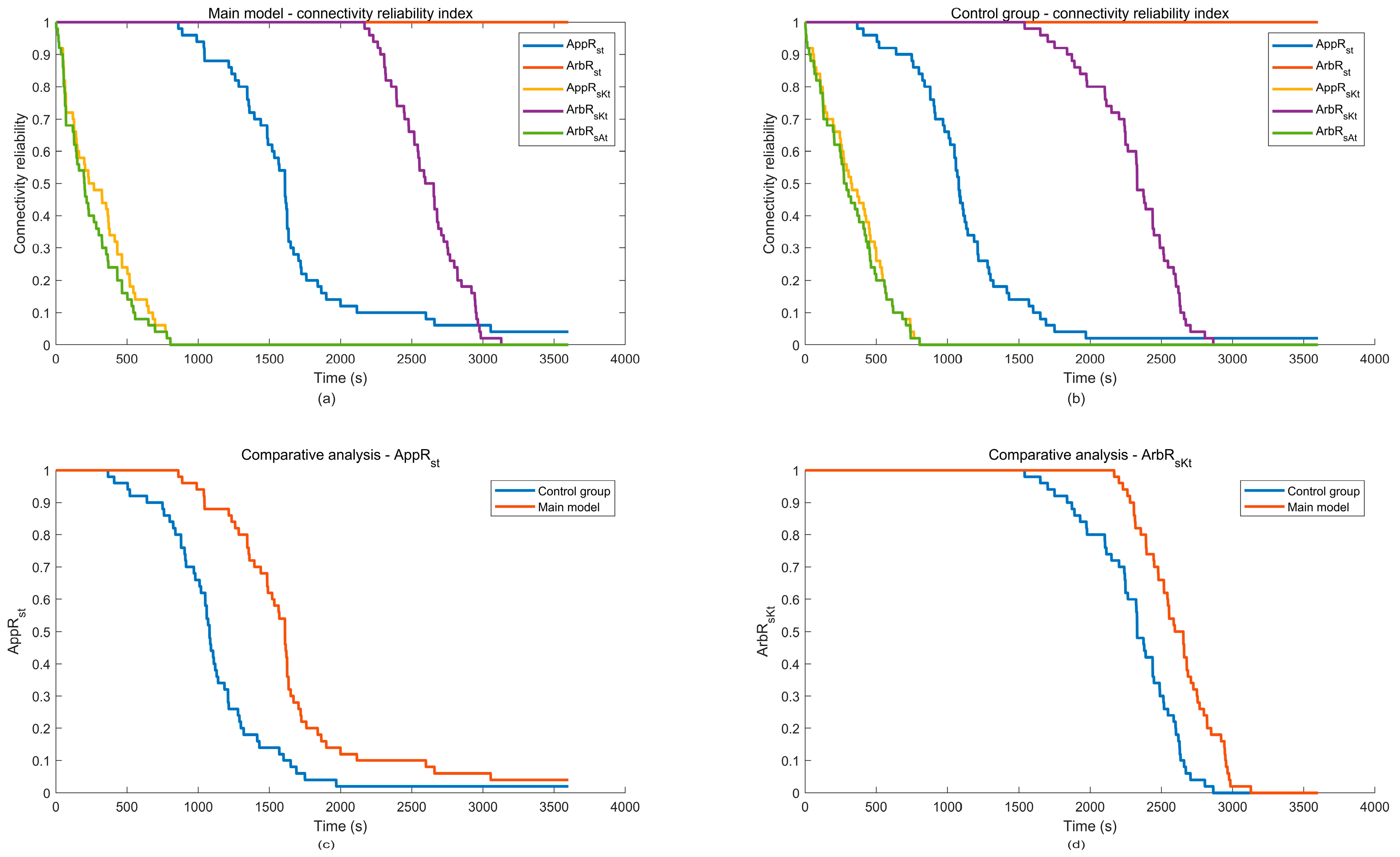

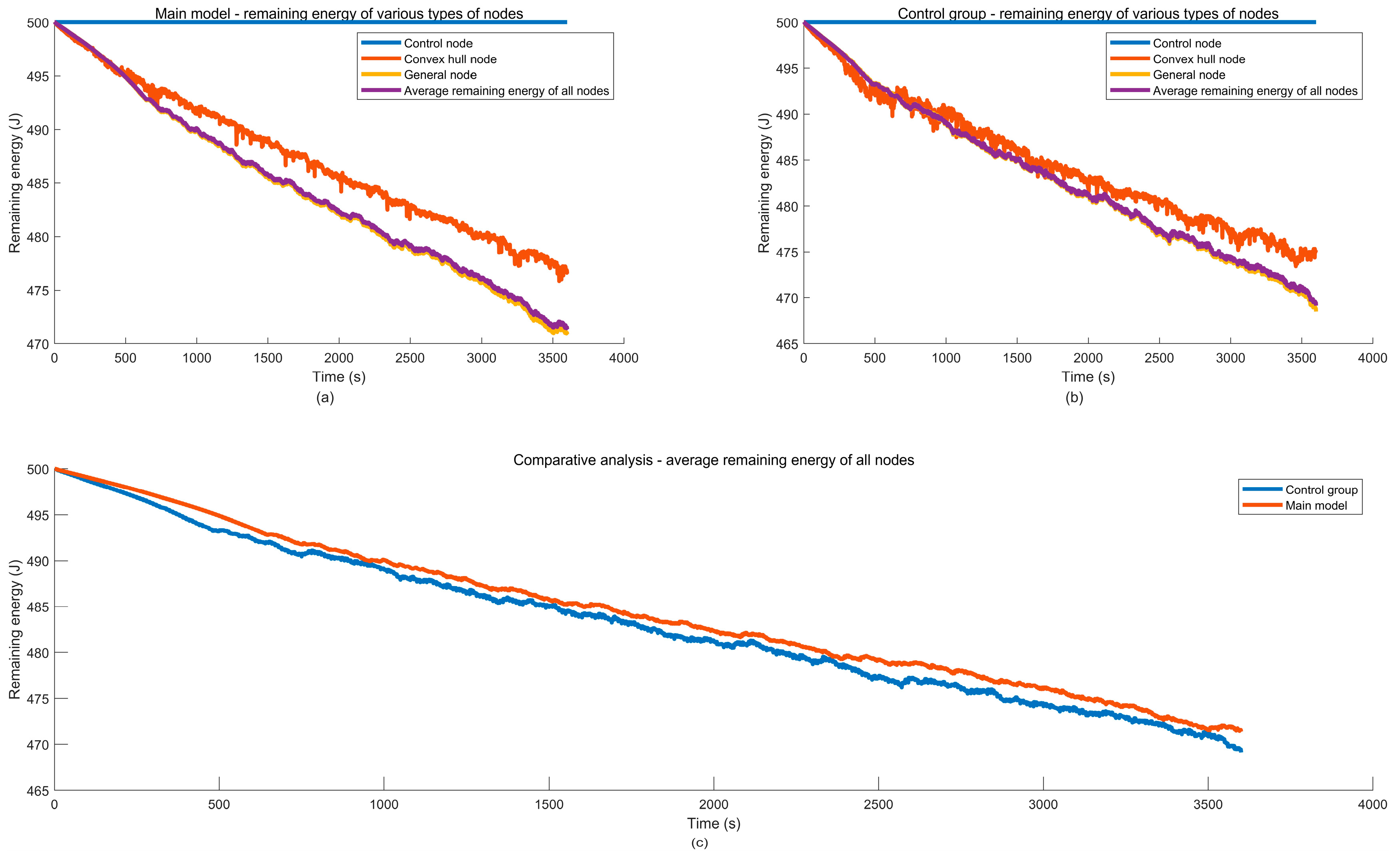

9.2. Simulation Case Result Analysis

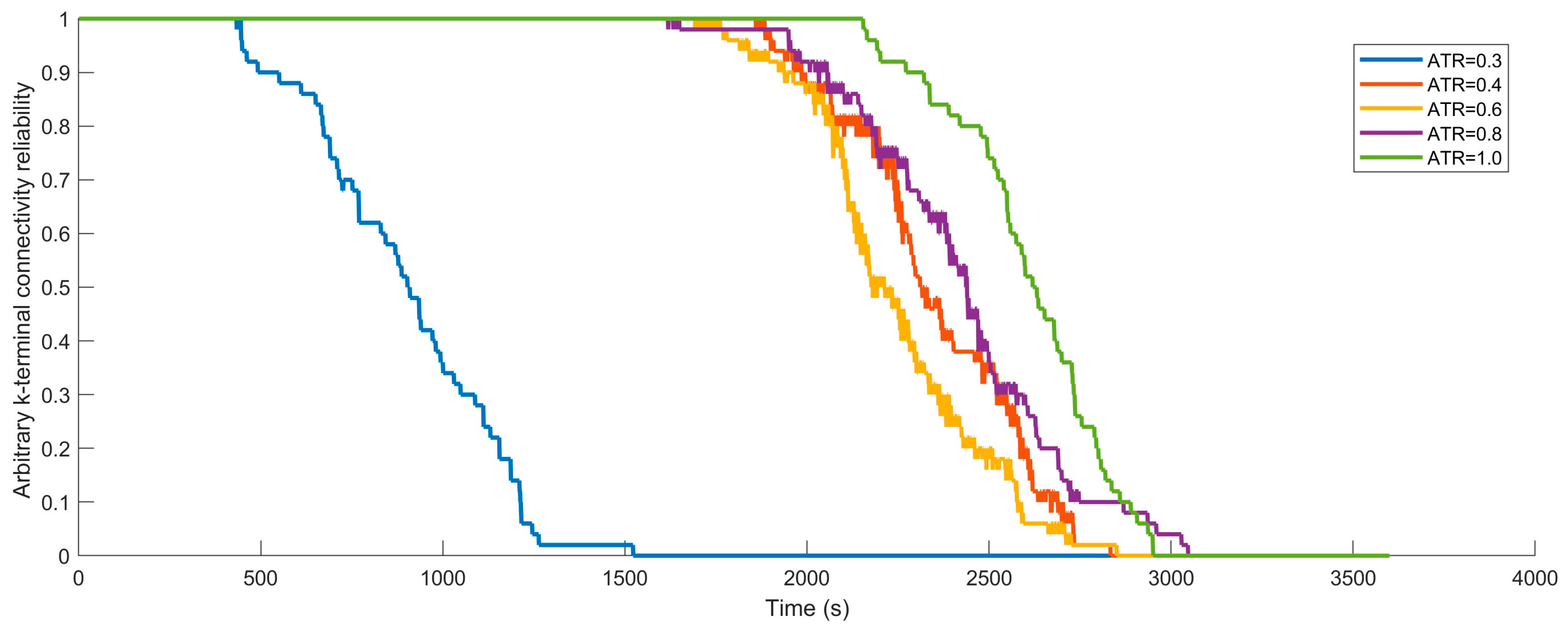

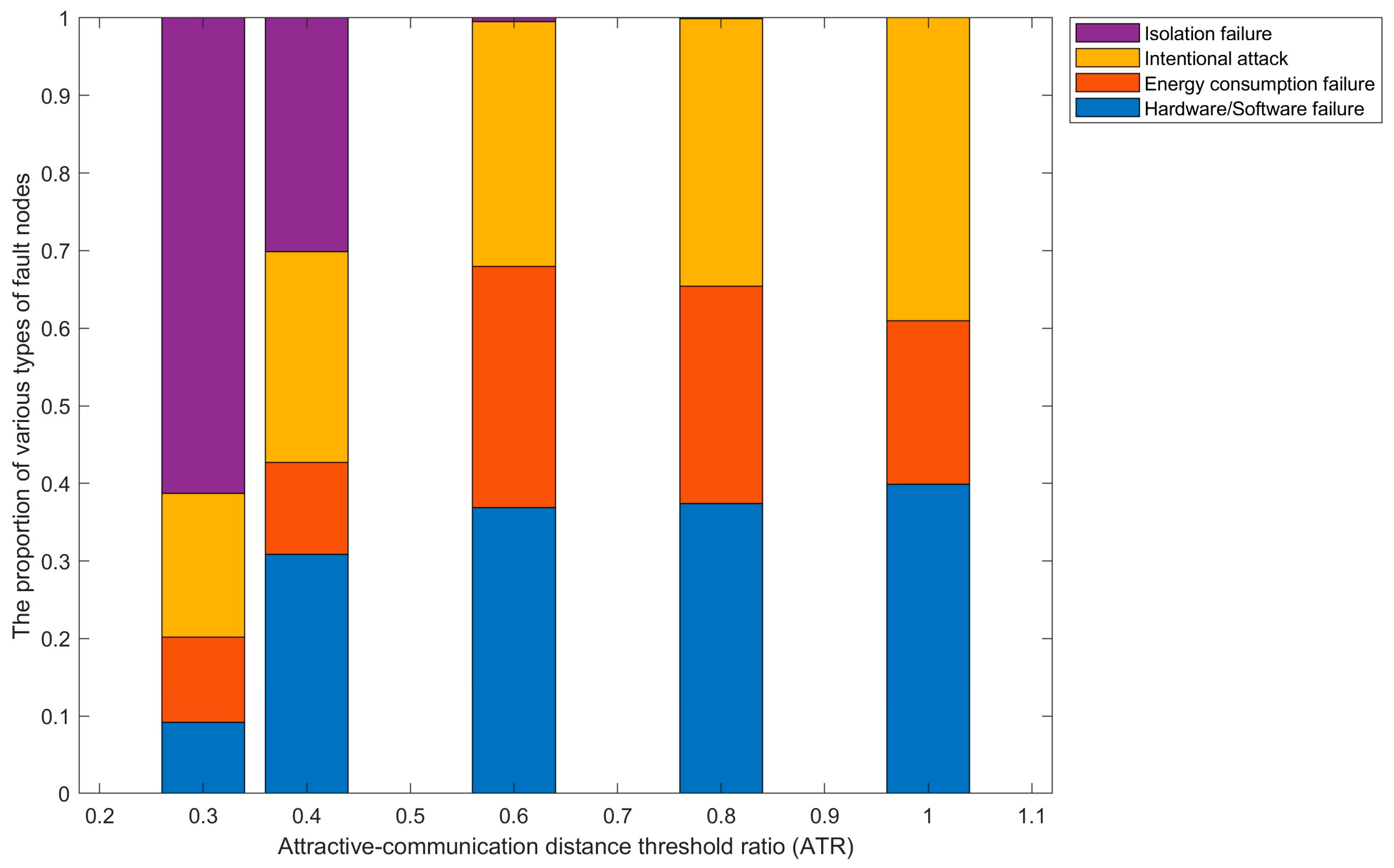

9.3. Sensitivity Analysis

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azni, A.H.; Ahmad, R.; Noh, Z.A.M.; Hazwani, F.; Hayaati, N. Systematic Review for Network Survivability Analysis in MANETS. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L. Cascading Failures in Internet of Things: Review and Perspectives on Reliability and Resilience. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsancakli, M.F.; Al Imran, M.A.; Yildiz, H.U.; Kara, A.; Tavli, B. Reliability of Linear WSNs: A Complementary Overview and Analysis of Impact of Cascaded Failures on Network Lifetime. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 131, 102839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, K.Y.; Girdler, T.; Vassilakis, V.G. A Survey of Cyber Security Threats and Solutions for UAV Communications and Flying Ad-Hoc Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 133, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Bai, G.; Liu, T.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.A.; Tao, J. An Improved Swarm Model with Informed Agents to Prevent Swarm-Splitting. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 169, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Bai, G.; Xu, B.; Tao, J. The Resilience Evaluation of Unmanned Autonomous Swarm with Informed Agents under Partial Failure. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harifi, S.; Razavi, A.; Rad, M.H.; Moradi, A. A Giza Pyramids Construction Metaheuristic Approach Based on Upper Bound Calculation for Solving the Network Reliability Problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, Y. Unlinkable Signcryption Scheme for Multi-Receiver in VANETs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 10138–10154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Le, J.; Wang, N.; Mu, N.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, T. PSRAKA: Physically Secure and Robust Authenticated Key Agreement for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 7953–7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y. Fully Anonymous Broadcast Signcryption for Secure Health Data Transmission in WBANs. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y. EFGDAS-MU: Efficient and Fine-Grained Data Aggregation Scheme for Multi-User in Cloud-Assisted IoT. Inf. Fusion 2025, 126, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Mohammadani, K.; Bashir, A.K.; Omar, M.; Jones, A.; Hassan, F. Secure and Reliable Routing in the Internet of Vehicles Network: AODV-RL with BHA Attack Defense. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 139, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cai, B.; Cozzani, V.; Liu, Y. Failure Dependence and Cascading Failures: A Literature Review and Research Opportunities. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 256, 110766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhong, J.; Bai, G.; Yang, Y. A Complex Networks Approach for Reliability Evaluation of Swarm Systems under Malicious Attacks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 81209–81219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, S.; Eftimie, R.; Painter, K.J. Leadership Through Influence: What Mechanisms Allow Leaders to Steer a Swarm? Bull. Math. Biol. 2021, 83, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, K.N.; Chan, M.C. Modeling Link Lifetime Data with Parametric Regression Models in MANETs. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2009, 13, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.C.; Huang, D.H.; Lin, Y.K.; Nguyen, T.P. Reliability and Maintenance Models for a Time-Related Multi-State Flow Network via d-MC Approach. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.F.; Xiang, H.Y.; Xu, X.Z. Expected Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Multi-Distribution Multi-State Logistics Network Based on Network Reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 251, 110321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Wei, P.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Broggi, M.; Beer, M. Sampling and Active Learning Methods for Network Reliability Estimation Using K-Terminal Spanning Tree. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 250, 110309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmaraja, S.; Vinayak, R.; Trivedi, K.S. Reliability and Survivability of Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks: An Analytical Approach. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2016, 153, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tian, T.-Z.; He, J.-T.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Yang, J. Transmission Reliability Evaluation of Wireless Sensor Networks Considering Channel Capacity Randomness and Energy Consumption Failure. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Bai, G.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.A.; Fang, Y. A Multistate Network Approach for Resilience Analysis of UAV Swarm Considering Information Exchange Capacity. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 241, 109606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, X.; Xing, L.; Peng, R. Systematic Review and Future Perspectives on Cascading Failures in Internet of Things: Modeling and Optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 254, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathy, N.; Chaturvedi, S.K. Evaluation of Mobile Ad Hoc Network Reliability Using Propagation-Based Link Reliability Model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2013, 115, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, K.; Maheshwari, A.; Saravanan, K.; Vidyasagar, S.; Kalyanasundaram, V.; Sattianadan, D.; Bereznychenko, V.; Narayanamoorthi, R. A Novel Network Lifetime Maximization Technique in WSN Using Energy Efficient Algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, N.; Coit, D.W.; Felder, F.A. Combined Effects of Load Dynamics and Dependence Clusters on Cascading Failures in Network Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 170, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Yang, J. Performance Reliability Evaluation for Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 169, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, S.; Babu, A.V. Link Residual Lifetime-Based next Hop Selection Scheme for Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2017, 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regragui, Y.; Moussa, N. Impact of Mobility Design on Network Connectivity Dynamics in Urban Environment. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2022, 119, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Parthiban, A.R.K. DTMR: An Adaptive Distributed Tree-Based Multicast Routing Protocol for Vehicular Networks. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2022, 79, 103551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, A.J.; Seno, S.A.H.; Naser, J.I.; Hajipour, J. DMPFS: Delay-Efficient Multicasting Based on Parked Vehicles, Fog Computing and SDN in Vehicular Networks. Veh. Commun. 2022, 36, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Latif, Z.; Javed, S.; Biswas, S.; Ajmal, S.; Iqbal, U.; Raza, M.; Khan, A.U. Routing Protocols in Vehicular Adhoc Networks (VANETs): A Comprehensive Survey. Internet Things 2023, 23, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dui, H.; Zhang, H.; Dong, X.; Zhang, S. Cascading Failure and Resilience Optimization of Unmanned Vehicle Distribution Networks in IoT. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 246, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yang, Y. Analysis on Invulnerability of Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Cellular Automata. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 212, 107616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.S.; Padmavathy, N. A Hybrid Link Reliability Model for Estimating Path Reliability of Mobile Ad Hoc Network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Sun, L. A Novel Layer-by-Layer Recursive Decomposition Algorithm for Calculation of Network Reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walikar, G.A.; Biradar, R.C. A Survey on Hybrid Routing Mechanisms in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 77, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couzin, I.D.; Krause, J.; Franks, N.R.; Levin, S.A. Effective Leadership and Decision-Making in Animal Groups on the Move. Nature 2005, 433, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Du, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, X. UAV-Enabled IoT: Cascading Failure Model and Topology-Control-Based Recovery Scheme. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 22562–22577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Johnson, B.W. Reliability Theory and Practice for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3548–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, Q.; Li, W. Modeling and Analysis of Industrial IoT Reliability to Cascade Failures: An Information-Service Coupling Perspective. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 239, 109517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ma, T.; Shu, N.; Liu, C.; Wu, T.; Chang, C. Is Your Solution Accurate? A Fault-Oriented Performance Prediction Method for Enhancing Communication Network Reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 256, 110793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature | Research Object | Evaluation Indicators | Node Failure Modes | Link Connection Model | Mobility Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | VANETs | Reliability, survivability | Hardware failures | Probabilistic | / (Simplified) |

| [28] | VANETs | Communication reliability | / (Not considered) | Probabilistic | Gauss-Markov mobility model |

| [29] | VANETs | Network performance | / (Not considered) | Deterministic | Microscopic mobility model |

| [30] | VANETs | Reliability | / (Not considered) | Deterministic | Car-Following Model |

| [31] | VANETs | Network performance | / (Not considered) | Deterministic | Realistic model of vehicular traffic |

| [32] | VANETs | Quality of Service (QoS) requirements | / (Not considered) | Probabilistic | Macroscopic mobility model |

| [33] | VANETs | Reliability, resilience | Cascading failures | Deterministic | / (Fixed nodes) |

| [34] | WSNs | Invulnerability | Intrinsic failure, external attack | Deterministic | / (Fixed nodes) |

| [27] | MANET | Transmission reliability | / (Not considered) | Probabilistic | Random direction mobility model |

| [35] | MANET | Connectivity reliability | Undefined but considered | Probabilistic | Random waypoint mobility model |

| [21] | WSNs | Transmission reliability | Random failure, energy consumption failure | Probabilistic | / (Fixed nodes) |

| Ours | VANETs | Connectivity reliability | Hardware/software failure, energy consumption failure, intentional attack, isolation failure | Deterministic | Improved Couzin-leader model |

| Node Type | Generate and Send Information Type | Cycle | Received Information Type | Relay Information Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| / | ||||

| / | ||||

| (Relay) | ||||

(Non-relay) | / |

| ITS | Source Node | Sink Nodes | Delivery Cycle | Send Information Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1 | , | |||

| ITS2 | ||||

| ITS3 |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| the energy consumption of the circuit for transmitting 1 bit of information | |

| the power consumption coefficient of the power amplification circuit | |

| the interference factor of the environment at time | |

| the control information | |

| the situational awareness information | |

| the coordinate information | |

| at time | |

| at time | |

| to a distance at time | |

| at time | |

| the interval period for real-time control information to be sent | |

| the interval period for coordinate information to be sent | |

| the minimum velocity of nodes | |

| the maximum velocity of nodes | |

| the safety distance between nodes to avoid collision | |

| the mutual attraction distance between nodes | |

| a unit vector, indicating the overall task information of VANETs | |

| a weight term to measure the degree of knowledge of task information | |

| the area where VANETs execute tasks | |

| the duration of VANETs task execution | |

| is the target point coordinate | |

| is the number of nodes in VANETs | |

| node | |

| the control node | |

| the convex hull set | |

| the action node set | |

| at time | |

| at time | |

| at time | |

| the set of nodes with normal communication functions | |

| the set of nodes with hardware/software failure | |

| the set of nodes with energy consumption failure | |

| the set of nodes under attack | |

| the set of nodes with isolation failure | |

| a random number | |

| failure at time indicates isolation failure | |

| the Euclidean distance matrix between nodes in VANETs | |

| the binary communication connectivity adjacency matrix of VANETs | |

| the energy threshold | |

| the simulation time step | |

| simulation experiment | |

| works normally at time | |

| works normally at time | |

| normally communicating connected nodes at time is greater than or equal to 2 | |

| the indicator function for judging the appointed at time | |

| at time | |

| at time is equal to |

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | m | 10 | s | ||

| 20 | m | 500 | J | ||

| 100 | m | 10,000 | h | ||

| 20 | km/h | 1 | s | ||

| 40 | km/h | (19,000, 19,000) | m | ||

| 100 × 10−9 | J/bit | [1, 1] | / | ||

| 100 × 10−12 | J/bit/m2 | 3 | / | ||

| 2 | / | 1 | / | ||

| 10 | KB | 5 | / | ||

| 10 | KB | 120 | / | ||

| 4 | KB | / | |||

| 5 | s |

| Ranks | Experimental Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Main Model | Control Group | |

| 1 | Hardware/software failure (14.56%) | Energy consumption failure (15.07%) |

| 2 | Intentional attacks (13.87%) | Intentional attacks (13.79%) |

| 3 | Energy consumption failure (7.79%) | Hardware/software failure (13.35%) |

| 4 | Isolation failure (0) | Isolation failure (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Bian, Y.; He, C.; Liu, F.; Xu, D.; Guo, Y. Evaluation of Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Considering Node Mobility and Multiple Failure Modes. Sensors 2025, 25, 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196073

Cao J, Bian Y, He C, Liu F, Xu D, Guo Y. Evaluation of Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Considering Node Mobility and Multiple Failure Modes. Sensors. 2025; 25(19):6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196073

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Junhai, Yunlong Bian, Chengming He, Fusheng Liu, Dan Xu, and Yiming Guo. 2025. "Evaluation of Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Considering Node Mobility and Multiple Failure Modes" Sensors 25, no. 19: 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196073

APA StyleCao, J., Bian, Y., He, C., Liu, F., Xu, D., & Guo, Y. (2025). Evaluation of Connectivity Reliability of VANETs Considering Node Mobility and Multiple Failure Modes. Sensors, 25(19), 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196073