Abstract

This paper addresses the problem of robust sensor faults detection and isolation in the air-path system of heavy-duty diesel engines, which has not been completely considered in the literature. Calibration or the total failure of a sensor can cause sensor faults. In the worst-case scenario, the engines can be totally damaged by the sensor faults. For this purpose, a second-order sliding mode observer is proposed to reconstruct the sensor faults in the presence of unknown external disturbances. To this aim, the concept of the equivalent output error injection method and the linear matrix inequality (LMI) tool are utilized to minimize the effects of uncertainties and disturbances on the reconstructed fault signals. The simulation results verify the performance and robustness of the proposed method. By reconstructing the sensor faults, the whole system can be prevented from failing before the corrupted sensor measurements are used by the controller.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, industrial applications need increasingly reliable approaches to operate at a high level of performance. Fault Detection and Isolation (FDI) methods are becoming much more effective at making a process reliable [1]. The sensor faults are the most frequent faults that occur in many control systems such as wind turbines [2], motor drives [3], electro-hydraulic and rotating machines [4,5], power systems and renewable energies [6].

In the presence of unknown signals, the earliest observer (i.e., Luenberger observer [7]) may be unable to force the output estimation error to converge to zero, and consequently the observer states will not converge to system states [8]. In the presence of disturbances and faults, a sliding mode observer (SMO) can be used to minimize the effect of disturbances on fault reconstruction signals [9]. In [10], the faults are reconstructed using a sliding mode observer in a system with no unknown signals. Sensor and actuator faults are reconstructed in [11] using an adaptive sliding mode observer in a 5 MW wind turbine system. The second-order sliding mode observer (SOSMO) is becoming a more interesting method these days [12,13]. Chattering reduction, higher accuracy motion, and finite-time convergence for dynamical systems are three important features of SOSMO [14,15].

Heavy-duty diesel engines are industrial equipment which is generally commercial equipment with GVWR (Gross Vehicle Weight Rating) of 10,000 pounds or more. Diesel engines have several advantages over gasoline engines, like creating an optimal compromise between fuel consumption and given exhaust legislation level by producing the requested torque [16]. Model predictive control in [17,18] and sliding mode control in [19] are two common control strategies in diesel engine air-path systems.

Sensor faults can thoroughly damage the system. With the loss of accuracy and showing a constant value rather than the true value due to the loss of sensitivity of sensors, reconstruction of these faults has currently become more crucial. There are several methods for fault reconstruction in industrial processes. In [20], two design methods were proposed to reconstruct known and unknown faults for a class of nonlinear systems using linear matrix inequality (LMI). In [21], a terminal sliding-mode observer (TSMO) was proposed for reconstructing faults in a class of second-order multi-input and multi-output (MIMO) nonlinear systems. In [22], considering the actuator and sensor faults of Markovian jump systems, a fault reconstruction-based method was developed using two novel observer schemes. In [23], a sliding mode observer was designed for the fault diagnosis problem of a linear time-invariant system. An adaptive super twisting observer was used in [4] for fault reconstruction in electro-hydraulic systems in the presence of uncertainties. Multiple sliding mode observers in the cascade were proposed in [24] for robust fault reconstruction in uncertain linear systems. In [25], a sliding mode observer was suggested for the fault reconstruction problem in a Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy descriptor system. In [26], a higher terminal sliding mode observer was proposed for robust fault reconstruction of the nonlinear Lipschitz system using the LMI concept. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the investigation of sensor fault in an engine air-path has not been reported yet. This problem is addressed in this paper. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- A diesel engine air-path system is studied completely, and by considering the sensor faults and disturbances which can affect the system, a complete model of the air-path system is presented.

- The nonlinear discontinuous term causes chattering of fault reconstruction, while proper higher-order sliding mode observer can weaken this problem. A higher-order sliding mode observer can also eliminate the deviation from true states and fault reconstruction in the presence of disturbances. Therefore, in the next step, a second-order sliding mode observer is designed.

- Although this paper’s approach is developed for a diesel engine air-path system, it can be broadened to other industrial processes and applications for reconstructing various possible faults in the presence of disturbances.

The proposed sensor fault reconstruction method is investigated according to the designed observer, and the simulation results for an air-path of a heavy-duty diesel engine system are compared to a sliding mode observer based approach.

2. Diesel Engine Air-Path Modeling

2.1. Diesel Engine Overview

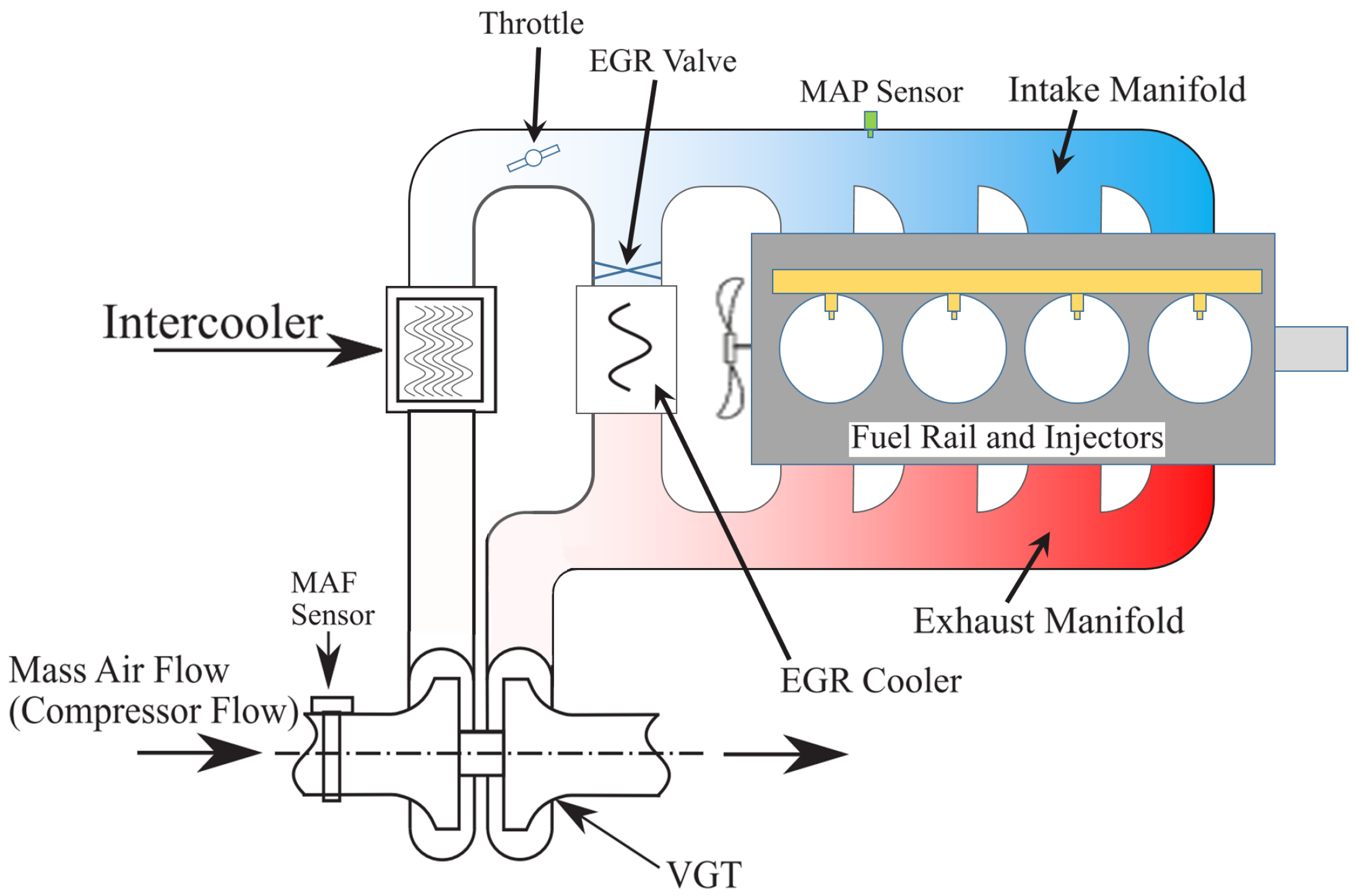

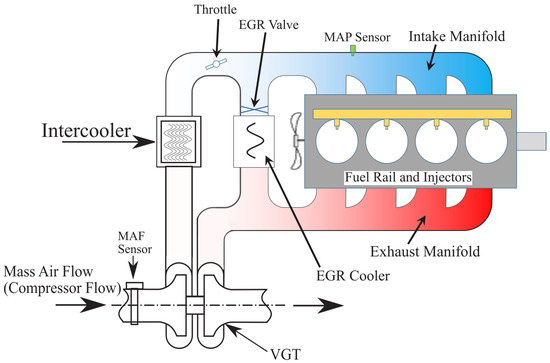

Diesel engines are a kind of energy converter which convert fuel energy into mechanical energy. They work according to supply, and heat is released by combustion in an engine forming a thermodynamic cycle [27]. Modeling and details of control methods for diesel engines have been studied in [28,29]. Figure 1 shows the diagram of the diesel engine air-path system.

Figure 1.

A diesel engine air-path diagram.

2.2. Manifold Modeling

The dynamics of diesel engine air-path system is modeled as follows:

where is the intake gas pressure and is considered as the system’s manifold. The system has the ideal gas constant for the air. is the intake gas temperature, which is assumed to be constant, and is the intake manifold volume. , and are the air rate, Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) rate and the cylinder mass flow rate, respectively.

2.3. Turbocharger Speed Modeling

According to Newton’s second law,

where is the mechanical efficiency of the turbocharger and is the rotating inertia of the turbocharger. and are the turbine power and the compressor power, respectively, which are calculated as follows:

where is the turbine efficiency, is the compressor efficiency, is the heat capacity of exhaust gas, is the heat capacity ratio of exhaust gas, is the heat capacity of intake gas and is the heat capacity ratio of intake gas. , , and are also the temperature of the gas in the exhaust before the turbine, the ambient temperature of the intake gas, the exhaust pressure before the turbine, the pressure ratio of the downstream pressure of EGR valve, respectively. By considering density variation in the mass flow, the turbine mass flow is modeled as

where is the effective area that the gas flow through, modeled as [19]

where is the maximum nominal flow area of the variable-geometry turbocharger (VGT) actuation, and and are the VGT actuator dynamic and a constant value, respectively. shows that the mass flow depends on the pressure ratio and is equal to

where is the downstream pressure of turbine, and is constant.

2.4. EGR Mass Flow Modeling

The fluid flows (airflow and exhaust gas flow) through the engine are controlled by the EGR throttle, EGR valve and variable geometry turbocharger (VGT). The EGR-valve mass flow through a variable area is modeled as

where is the ideal gas constant for exhaust. is a function of the pressure ratio of and . is the effective flow area of EGR valve, and is calculated as [19]

where is the maximum nominal flow area of EGR actuation, and and are EGR actuator dynamic and a constant value, respectively. In (1), the term is called compressed air-flow and is modeled as

where and are the radius of the compressor blade and volumetric flow coefficient, respectively.

2.5. Cylinder Flow Modeling

From the intake manifold to the cylinders, the cylinder mass flow model is obtained as

where , and are the volumetric efficiency, the engine speed and the displaced volume, respectively.

2.6. Unified Model of a Diesel Engine Air-Path

By combining Equations (1)–(9), the state-space model of a diesel engine air-path is obtained as follows:

where

In (11), the state vector and the control input vector are denoted as and , respectively, where and are the VGT and EGR normalized actuator signals.

2.7. Disturbance and Sensor Fault Modeling

In this system, the measured disturbance is the engine speed (). The faults in the manifold air pressure sensor, which is used to measure the intake gas pressure, and EGR mass flow rate sensor are considered. The EGR mass flow rate sensor is located in the path of the EGR valve and the intake manifold in Figure 1. Note that the EGR mass flow rate is estimated by the measured pressures on both sides of the EGR system. Accordingly, from (11), the output state-space model will be written as

where and are the manifold gas pressure sensor fault and the EGR mass flow rate sensor fault, respectively.

Finally, the model of diesel engine air-path system in the presence of external disturbance and sensor faults is obtained as

where , , , and are the distribution matrices of state, control input, disturbance, output and sensor fault, respectively.

Consider a new state that filters the output given by

where − is a stable matrix. Substituting from (14) into (15) gives

From (14) and (16), the augmented state-space model with states is achieved as

Equation (17) can be written as

The output in (18) has formed by the combination of the actual and filtered outputs. It is also assumed that .

To obtain a canonical form for the augmented system (18), a transformation matrix T is introduced, so the canonical form is obtained using . For this case, the following model is achieved:

where , , , and .

3. Sensor Fault Reconstruction Using Second-Order Sliding Mode Observer

A second-order sliding mode observer for (19) is presented as follows:

where and denote the estimation of states and outputs, respectively. and are the observer gains which will be defined later. In (19), is a nonlinear discontinuous term used to induce the sliding motion.

The output estimation error is defined as

where is the state estimation error. From (18) and (19), one gets

To force the output estimation error to zero in the finite time, the sliding mode surface will be presented as

The second-order sliding mode output error injection is presented as follows:

where , and are the design scalars.

The gain is chosen as

where L has the following structure:

where is designed such that is Hurwitz and is also the first rows of .

The observer gain matrix is also designed in terms of L and a chosen design matrix . This chosen matrix can be calculated as the following form [30]:

The coefficients , , and k are chosen as

where is sufficiently large, then converges to the origin in the finite time.

The sensor fault reconstruction signal is presented as

where the matrix needs to be designed such that . As and converge to zero in the finite time, then, from (22) one obtains

Multiplication of both sides in (30) by M implies

From (29), one gets:

Therefore, the effect d on the fault reconstruction signal will be minimized if

where is a small positive scalar.

Let define P in the following form:

where and . Using the Bounded Real Lemma (BRL), the inequality (34) is converted to

By obtaining P and M from (35) and substituting M into (32), one obtains

This concludes the result.

4. Simulation Results

To illustrate the accuracy of the results presented in this paper, a state-space model of a heavy-duty diesel engine with initial conditions of is obtained as follows:

The value and description of the real system’s parameters are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The value and description of the real system’s parameters.

By choosing , the following augmented system is obtained:

To obtain a canonical form, we define a matrix T:

Therefore, the matrices are transformed to

and the matrices , and M are designed as

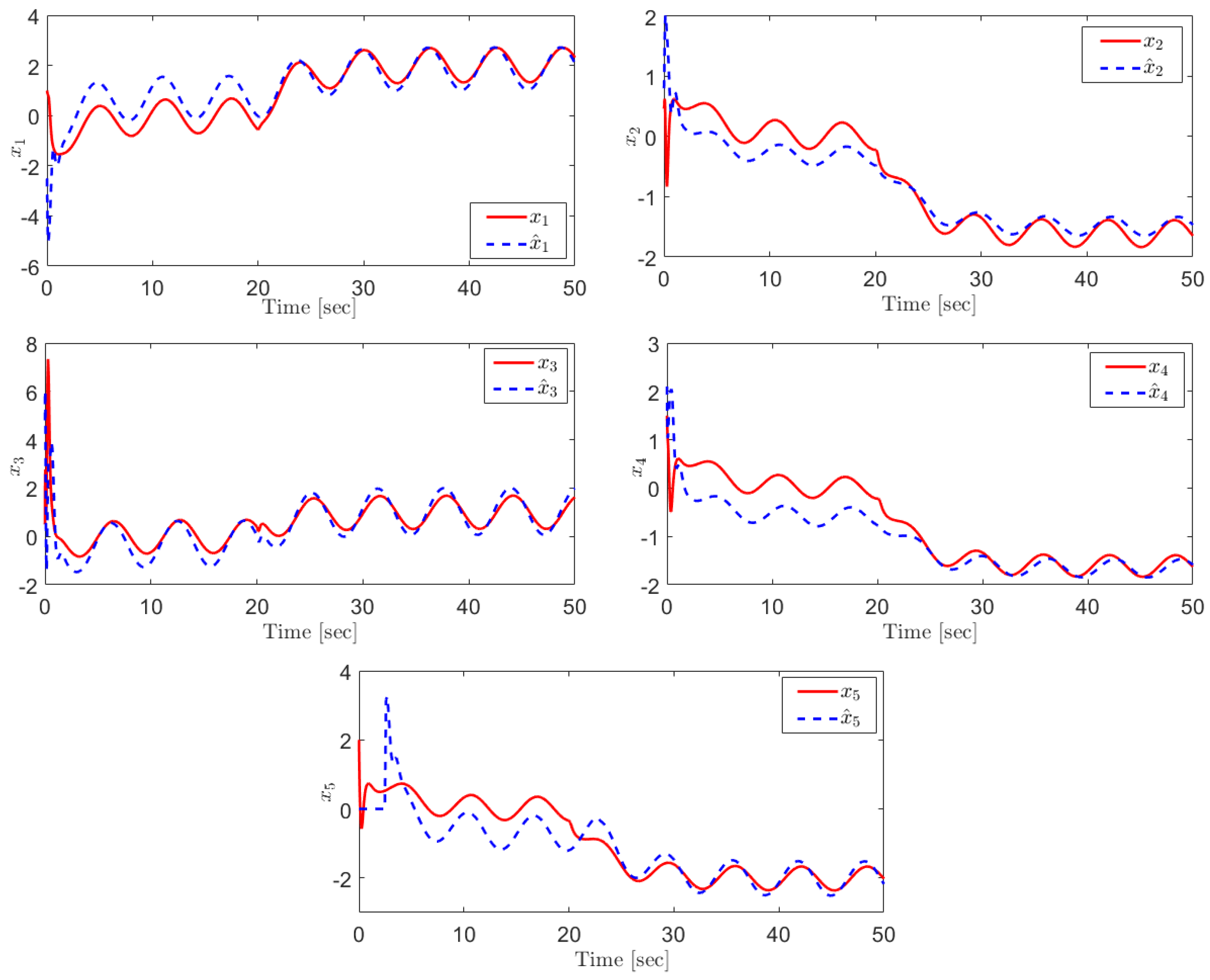

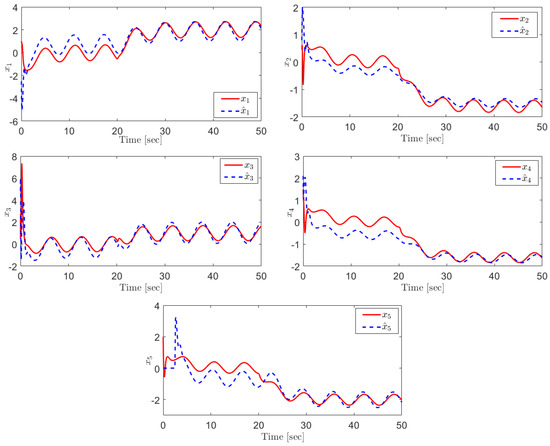

Choosing , the observer parameters have been chosen as , , and . Figure 2 shows the states and their estimation. As can be seen, although there is a disturbance signal in the system, each state accurately tracks its estimation signal in the finite time.

Figure 2.

The real states and their estimations.

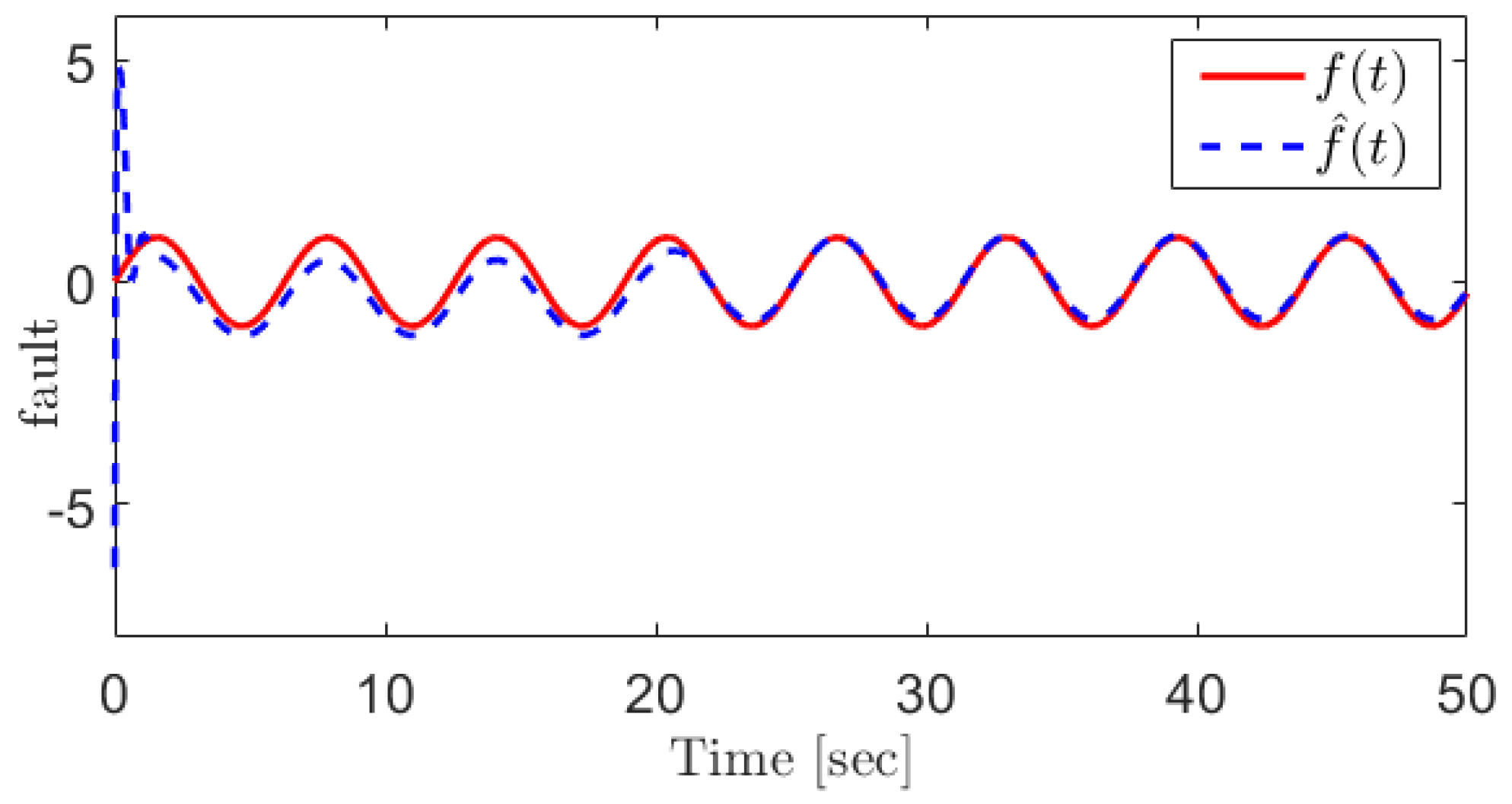

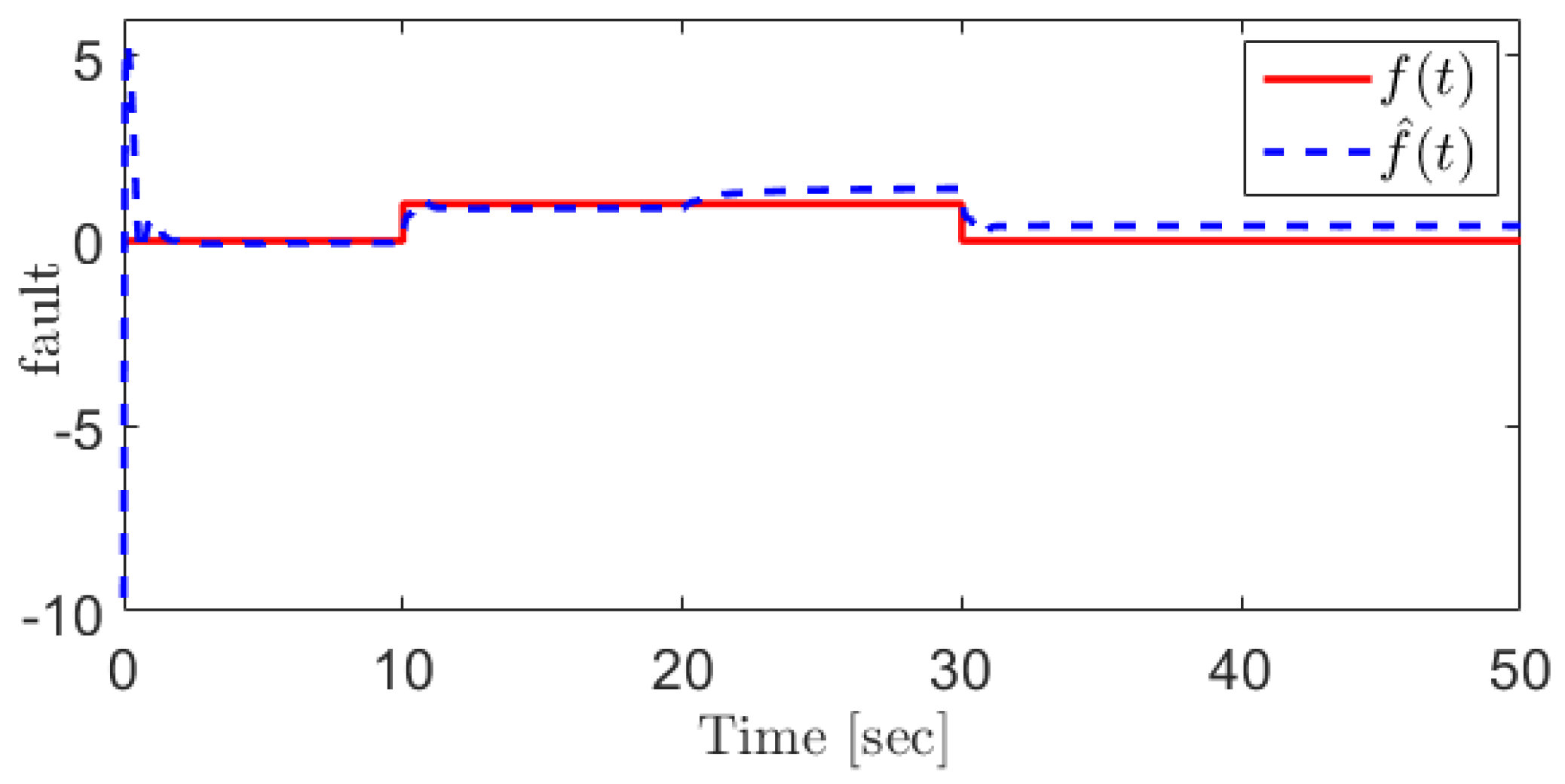

For the manifold gas pressure sensor fault, we consider the following fault:

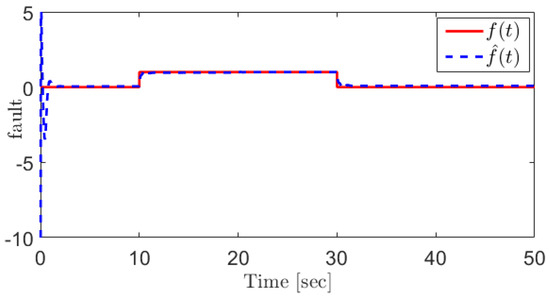

Figure 3 shows the fault and its reconstruction signal indicating that the sensor faults can be reconstructed using the proposed method.

Figure 3.

The manifold gas pressure sensor fault and its reconstruction using the proposed SOSMO method.

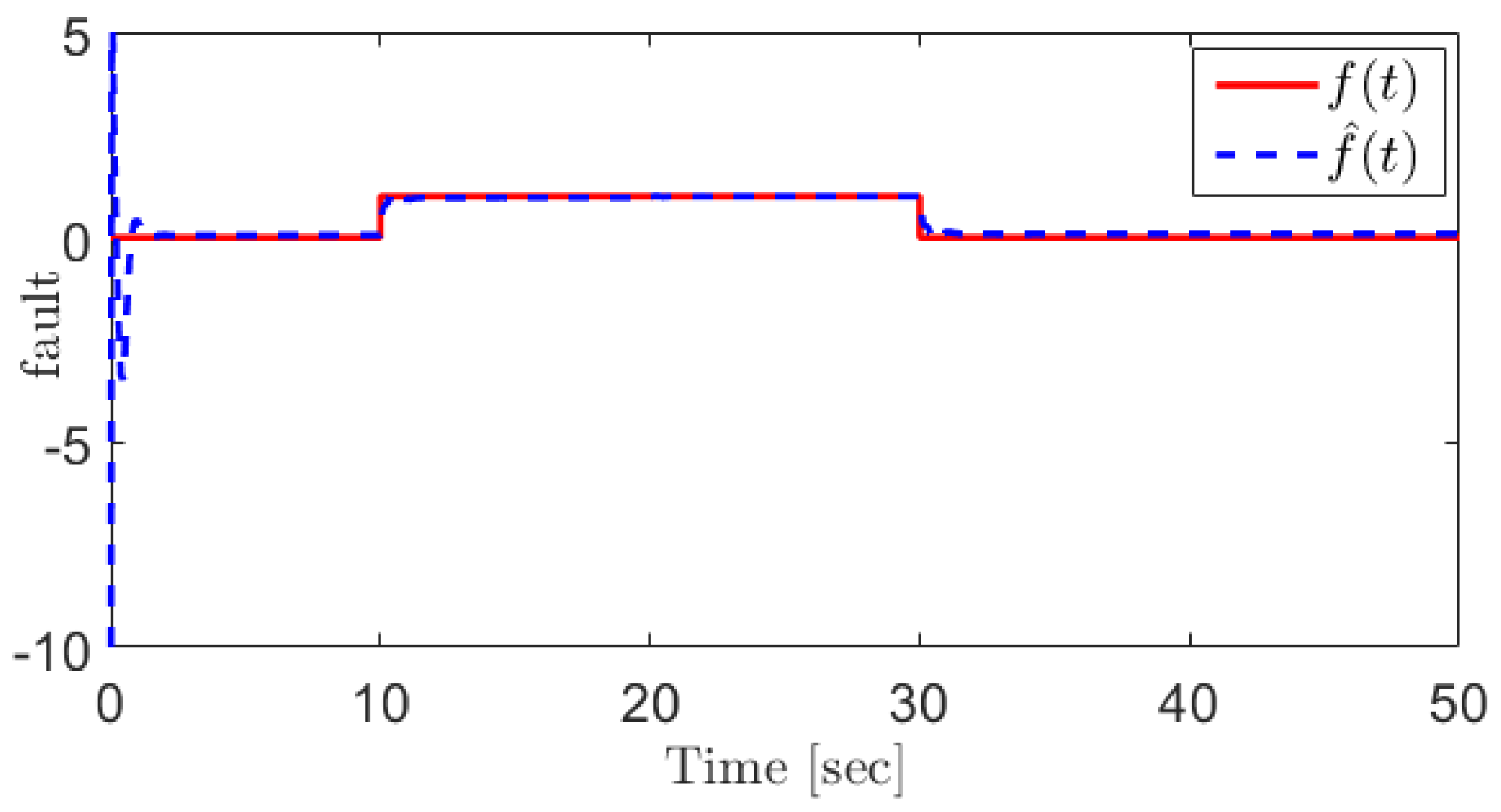

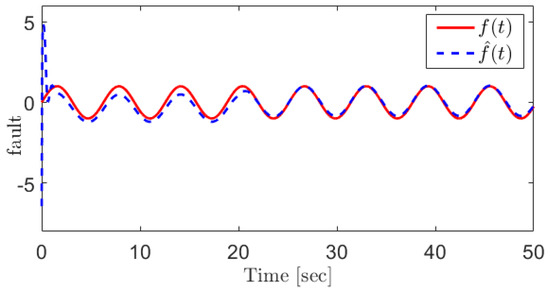

For the EGR mass flow rate sensor fault, the following fault is assumed:

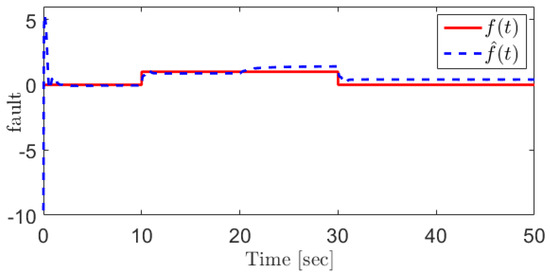

In this case, the fault can be reconstructed as Figure 4. For the sake of comparison, the sliding mode observer (SMO)-based approach proposed in [31] is applied for the EGR mass flow rate sensor fault reconstruction, and the corresponding result is shown in Figure 5. The results demonstrate that the proposed SOSMO has more robust performance when coping with the unknown disturbances.

Figure 4.

The EGR mass flow rate sensor fault and its reconstruction using the proposed SOSMO method.

Figure 5.

The EGR mass flow rate sensor fault and its reconstruction using SMO method [31].

Using some quantitative criteria, the performance of the proposed SOSMO method is investigated and compared with the SMO approach. To this aim, the following criteria are defined:

where denotes the simulation time. Table 2 provides the performance evaluation results for the observer and sensor fault, both for the manifold gas pressure sensor fault and EGR mass flow rate sensor fault. It also shows the result for the EGR mass flow rate sensor fault designed with SMO.

Table 2.

Quantitative performance evaluation.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a new robust strategy is proposed for sensor fault reconstruction in a heavy-duty diesel engine in the presence of disturbance. First, a SOSMO was designed using the LMI approach. Then, a sensor fault reconstruction strategy was introduced for the reconstruction of the manifold gas pressure sensor and EGR mass flow rate sensor faults. To verify the advantages of the SOSMO method, the EGR mass flow rate sensor fault reconstruction was compared with a SMO-based method. The results of this comparison were verified both numerically and graphically so that it was proved that the second-order sliding mode observer has more reliable results than the sliding mode observer. According to the results in Table 2, in the SOSMO method, the convergence of the states and the EGR mass flow rate sensor has improved 10.4% and 95.5%, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and F.B.; Data curation, A.T.; Formal analysis, A.T. and F.B.; Funding acquisition, A.B.; Investigation, F.B. and S.M.; Methodology, A.T., F.B. and S.M.; Resources, F.B.; Software, A.T., F.B. and S.M.; Supervision, F.B. and S.M.; Visualization, A.T.; Writing—original draft, A.T.; Writing—review and editing, F.B., S.M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen, N.P.; Mung, N.X.; Thanh Ha, L.N.N.; Huynh, T.T.; Hong, S.K. Finite-Time Attitude Fault Tolerant Control of Quadcopter System via Neural Networks. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarpour, K.; Bayat, F.; Jalilvand, A. Wind turbines sustainable power generation subject to sensor faults: Observer-based MPC approach. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 30, e12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Prieto, I.; Duran, M.J.; Rios-Garcia, N.; Barrero, F.; Martin, C. Open-switch fault detection in five-phase induction motor drives using model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 65, 3045–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Naraghi, M.; Zareinejad, M. Adaptive super-twisting observer for fault reconstruction in electro-hydraulic systems. ISA Trans. 2018, 76, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, A.; Hwang, H.; Kim, H.S. Synthetic Data Augmentation and Deep Learning for the Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machines. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarpour, K.; Bayat, F.; Jalilvand, A. Dependable power extraction in wind turbines using model predictive fault tolerant control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D. An introduction to observers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1971, 16, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, H.; Edwards, C.; Tan, C.P. Fault Detection and Fault-Tolerant Control Using Sliding Modes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, H.L.N.N.; Mung, N.X.; Nguyen, N.P.; Phuong, N.T. Perturbation observer-based robust control using a multiple sliding surfaces for nonlinear systems with influences of matched and unmatched uncertainties. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S.K.; Patton, R.J. Sliding mode observers for fault detection and isolation. Automatica 2000, 36, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, A.; Bayat, F. Wind turbines robust fault reconstruction using adaptive sliding mode observer. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 3096–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Obeid, H.; Laghrouche, S.; Cirrincione, M. Second order sliding mode observer of linear induction motor. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2019, 13, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Sun, S.; Walker, P.; Zhang, N. Accelerated adaptive second order super-twisting sliding mode observer. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 25232–25238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Robust exact differentiation via sliding mode technique. Automatica 1998, 34, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, I.; Fridman, L.; Pisano, A.; Usai, E. Analysis of chattering in systems with second-order sliding modes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2007, 52, 2085–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.; Sofiane, A.A.; Nicolas, L. Adaptive super twisting extended state observer based sliding mode control for diesel engine air path subject to matched and unmatched disturbance. Math. Comput. Simul. 2018, 151, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, G.S.; Shekhar, R.C.; Manzie, C.; Sano, T.; Nakada, H. Model predictive controller with average emissions constraints for diesel airpath. Control Eng. Pract. 2019, 90, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kekik, B.; Akar, M. Model predictive control of diesel engine air path with actuator delays. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Turesson, G.; Tunestål, P.; Johansson, R. Sliding mode control on receding horizon: Practical control design and application. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 109, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.S.; Chan, J.C.L.; Tan, C.P.; Chong, E.K.P.; Saha, S. Robust fault reconstruction for a class of nonlinear systems. Automatica 2020, 113, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Meng, F.; Zhu, D.; Luo, C. Fault reconstruction using a terminal sliding mode observer for a class of second-order MIMO uncertain nonlinear systems. ISA Trans. 2020, 97, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, P.; Liu, M. Fault reconstruction for Markovian jump systems with iterative adaptive observer. Automatica 2019, 105, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhirabok, A.; Shumsky, A.; Zuev, A. Fault diagnosis in linear systems via sliding mode observers. Int. J. Control 2019, 94, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.P.; Edwards, C. Robust fault reconstruction in uncertain linear systems using multiple sliding mode observers in cascade. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 55, 855–867. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Yang, Y. Sliding-mode observer-based fault reconstruction for TS fuzzy descriptor systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 51, 5046–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Fault Reconstruction for Lipschitz Nonlinear Systems Using Higher Terminal Sliding Mode Observer. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Sci. 2020, 25, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenhauer, K.; Tschöke, H.; Johnson, K.G. Handbook of Diesel Engines; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzella, L.; Onder, C. Introduction to Modeling and Control of Internal Combustion Engine Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, L.; Nielsen, L. Modeling and Control of Engines and Drivelines; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; El Ghaoui, L.; Feron, E.; Balakrishnan, V. Linear Matrix Inequalities in System and Control Theory; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.P.; Edwards, C. Sliding mode observers for robust detection and reconstruction of actuator and sensor faults. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control IFAC-Affil. J. 2003, 13, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).