Hands-On Experiences in Deploying Cost-Effective Ambient-Assisted Living Systems

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- Recent advances in low-power wireless communication networks have driven a shift towards ZigBee and emerging body area network (BAN) technologies. Technology trends indicate that Bluetooth and RFID will become less common in future AAL prototypes, mainly due to ZigBee’s low energy consumption, enhanced security features and ability to support mesh networks.

- The connectivity of AAL systems with the Internet and the access of remote care providers to activity and medical data via web and/or mobile application interfaces become key design requirements.

- AAL systems increasingly integrate a wide variety of sensors capturing a broad range of contextual parameters. Such sensors tend to be (although are not always) common, affordable devices that can easily be installed in the monitored environment with no significant effort and cost [1].

- Machine vision-based activity recognition becomes less common nowadays in AAL systems, mainly due to the inherent algorithmic complexity of relevant approaches, the proliferation of highly accurate sensor solutions (which easily capture presence and activity data) and the raising of privacy concerns thereby lowering user acceptance [1,28].

- The main focus of AAL research so far has been on system implementation and testing, sensor fusion and activity inference. Tackling challenges beyond technical issues (such as user acceptance problems, usability, user learning and user experience aspects) represents an emerging trend in AAL research [28,29].

- The attention of AAL research community gradually moves from the “traditional” ADL monitoring and fall detection systems to specialized application fields such as: dementia, Alzheimer and comorbidity care; cognitive and kinetic disabilities; heart surgery recovery; hearing impairments; total blindness; and medical emergency detection [30]. In many cases, wearable (body-worn) devices are used, which capitalize on recent advances in MEMS and epidermal electronics for monitoring health parameters (like blood pressure, heart rate, etc.) [1].

- It makes no assumptions on the existence of a smartphone or PC/laptop to collect activity reports or emergency data (apart from increasing deployment cost, such requirements would seriously compromise the reliability and availability of the system); rather, this role is undertaken by an inexpensive microcontroller, which only requires an Internet connection.

- UbiCare makes no use of cameras and microphones for activity recognition, acknowledging that such devices are commonly perceived as privacy violators, hence, undermining user acceptance for such systems. Instead, activity monitoring is undertaken by sensor devices which may easily be fabricated within furniture and home appliances, while the monitored subjects are required to carry minimal equipment (waived into their clothes) to mitigate their reluctance in accepting the system.

- Activity detection is based on monitoring the interaction of human subjects with a broad variety of home objects, including furniture, electrical appliances, faucets and sanitary facilities.

- UbiCare addresses the confidentiality requirements of privacy-sensitive activity information taking advantage of the XBee capabilities to enable secure data exchange on both the application and the network layers.

- We have investigated technical solutions to reduce the energy expenditure of XBee modules and battery-operated microcontrollers so as to prolong the system’s lifetime.

| Prototype/Release Date | Application Area | Activity Types Inferred | Sensor Node Platform and OS | Mounted Sensors | Wearable Sensors | Requirement for Additional Computing Infrastructure (to Collect Sensory Data) | Wireless Communication Technology | Support for Remote Monitoring | Unique Functional or Technical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philipose et al. [23]/2004 | ADL monitoring | Usage of appliances | Not specified | RFID tags on appliances | Gloves and bracelets with RFID tag readers | Not specified | RFID | Yes (activity reports) | Usage of activity models and approximate probabilistic inference to rapidly track those activities. |

| ITALH [3]/2005 | Fall detection; medical emergency detection | Motion events | Telos Rev B Mote (Berkeley) | Temperature, humidity and light sensors | Accelerometer, heart rate monitors | PC, mobile phone | ZigBee, Bluetooth | Yes (display of alarms and incidents of interest, live camera data) | Users explicitly decide who/when has access to health and activity data. |

| Nasution and Emmanuel [7]/2007 | Posture-based events monitoring; fall detection | Standing, sitting, bending/squatting, side laying, laying | - | Camera | - | PC | - | No | Intelligent posture recognition. |

| Behavior Scope [4]/2008 | ADL monitoring | Presence | Intel iMote2 | Motion sensors and cameras | - | Server computer | Not specified | Yes (display of notifications) | The system’s architecture offers a flexible, user-configurable time abstraction layer that encodes temporal information in the incoming (sensor) data stream. |

| Yu-Jin et al. [25]/2008 | ADL monitoring | Standing, lying, sitting, walking, running | - | RFID tags on everyday objects | Accelerometer, glove with RFID reader (iGrabber) | Smartphone | Bluetooth, RFID | No | Sensor fusion of three accelerometers and a RFID reader. |

| WASP [11]/2008 | ADL monitoring | Usage of appliances & objects, mobility, communication, eating, sleeping, preparing food, leaving & returning home | TinyOS | Microphones, pressure sensors, RFID tags, electricity and water usage sensors, cameras | Accelerometer, pulse oximeter | Mobile phone or PDA, PC | RFID | Yes (display of activity reports & statistics) | Multi-sensor fusion, behavior estimation, interoperation of heterogeneous sensor environments. |

| AlarmNet [20]/2008 | ADL monitoring | Presence in specific rooms, eating, hygiene, sleeping | MicaZ & Telos Sky motes/TinyOS | Temperature, light, dust, motion sensors | ECG, pulse oximeter, accelerometers | Crossbow Stargate SBC | ZigBee | Yes (display of alarms, sensor data, activity reports & statistics) | Extensible heterogeneous network middleware, smart power management, activity pattern learning, dynamic alert-driven privacy. |

| Zhongna et al. [8]/2009 | ADL monitoring | Standing, walking etc. | - | Cameras | - | Micro-computer | Not specified | No | Efficient silhouette extraction for privacy protection, automated activity analysis. |

| Putnam et al. [5]/2012 | Fall detection | - | Arduino | - | Accelerometer | PC | ZigBee | Yes (display of fall events) | Location tracking based on received signal strength. |

| Ranjitha Pragnya et al. [26]/2013 | ADL monitoring; wellness monitoring | Usage of household appliances | ARM ATMEL | Temperature, force sensing resistors | MEMS | PC | ZigBee | No | Non-invasive, flexible, low-cost home monitoring. |

| Suryadevara et al. [27]/2013 | ADL monitoring; determination of wellness | Sitting, sleeping, usage of household appliances and objects | - | Force sensing resistors, current flow sensors | - | PC | ZigBee | Yes (activity reports & statistics) | Intelligent behavior detection; behavior and wellness forecasting. |

| WiSPH [21]/2014 | Fall detection; medical emergency detection | Motion | WiSe platform [33] | - | Accelerometer, heart rate sensor | PC | ZigBee, Bluetooth | Yes (display of alarms and health status via web interface) | Efficient fall detection algorithm. |

| UbiCare | ADL monitoring; fall detection | Presence in specific rooms, sitting, sleeping, eating, hygiene, usage of household appliances | Arduino | Motion, force, temperature, humidity, light, electricity and water usage sensors | Accelerometer | - | ZigBee | Yes (display of alarms, activity reports & statistics via web interface) | Unobtrusive and low cost deployment; no requirement for PC, micro-computer to collect sensory data; privacy, wireless security and energy saving considerations are addressed. |

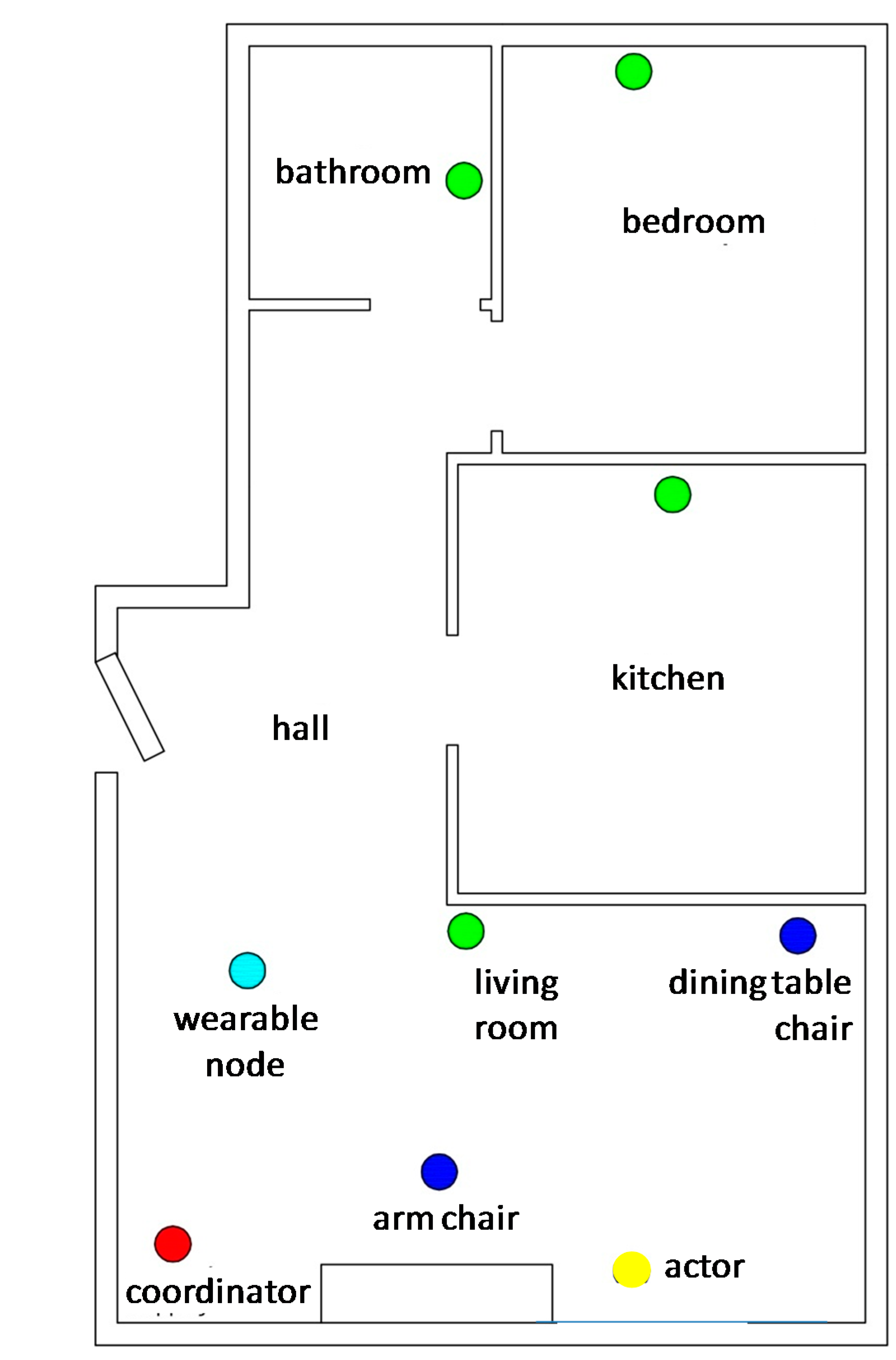

3. Experimental Testbed

| Node | Activity Type | Hardware | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedroom node |

|

| $97 |

| Living room node |

|

| $67 |

| Kitchen node |

|

| $73 |

| Bathroom node |

|

| $65 |

| Arm chair node |

|

| $35 |

| Dining table chair node |

|

| $34 |

| Wearable node |

|

| $83 |

| Actuator node | - |

| $29 |

| Coordinator node | - |

| $98 |

4. Implementation Issues

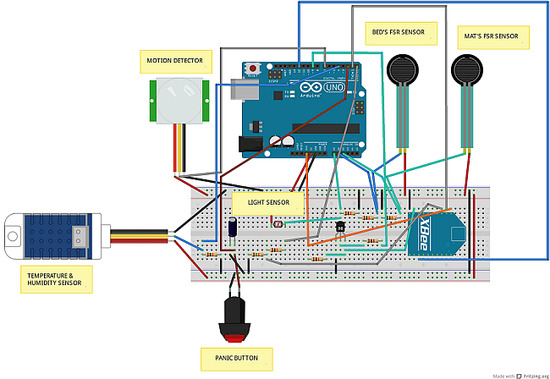

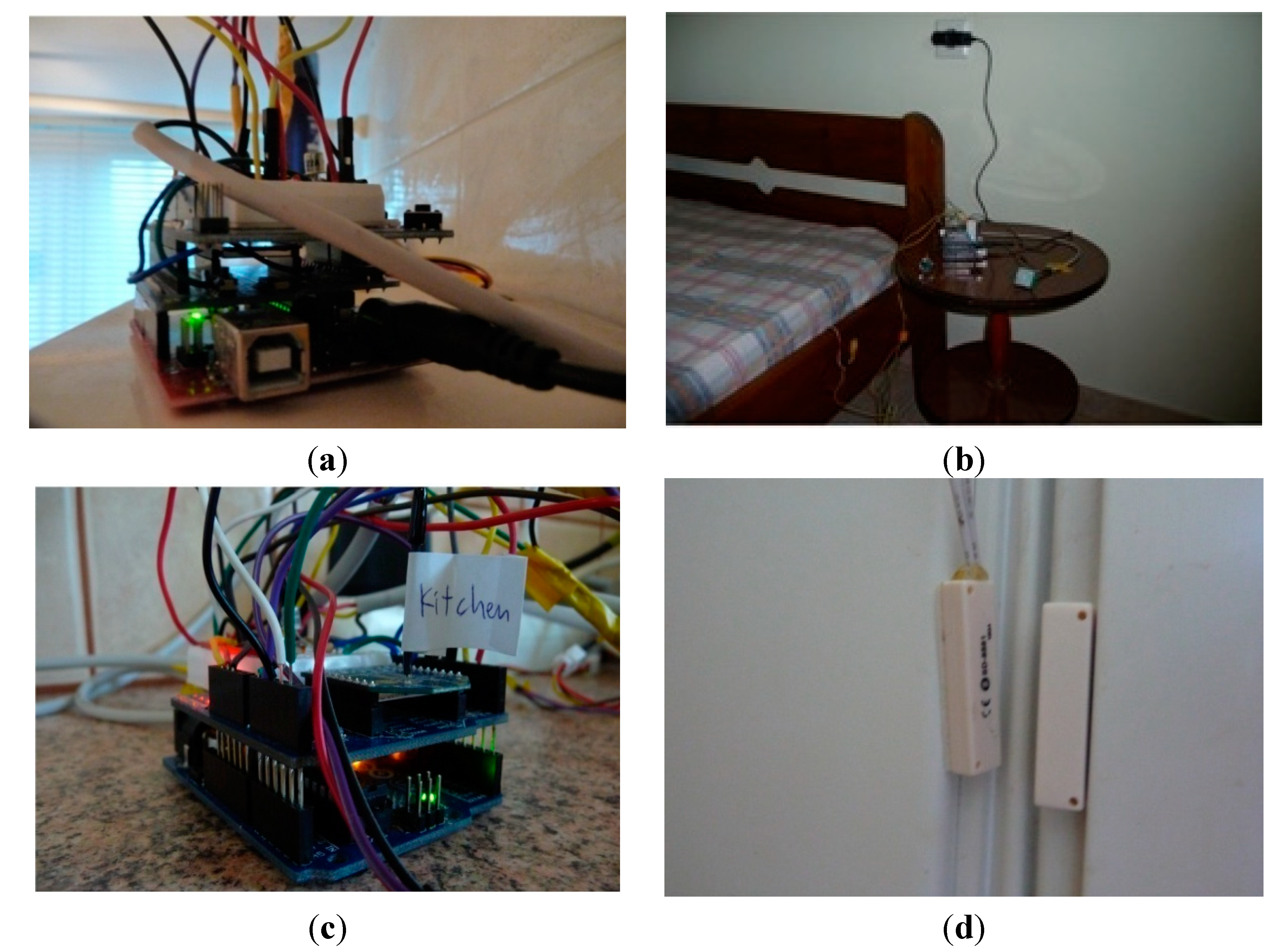

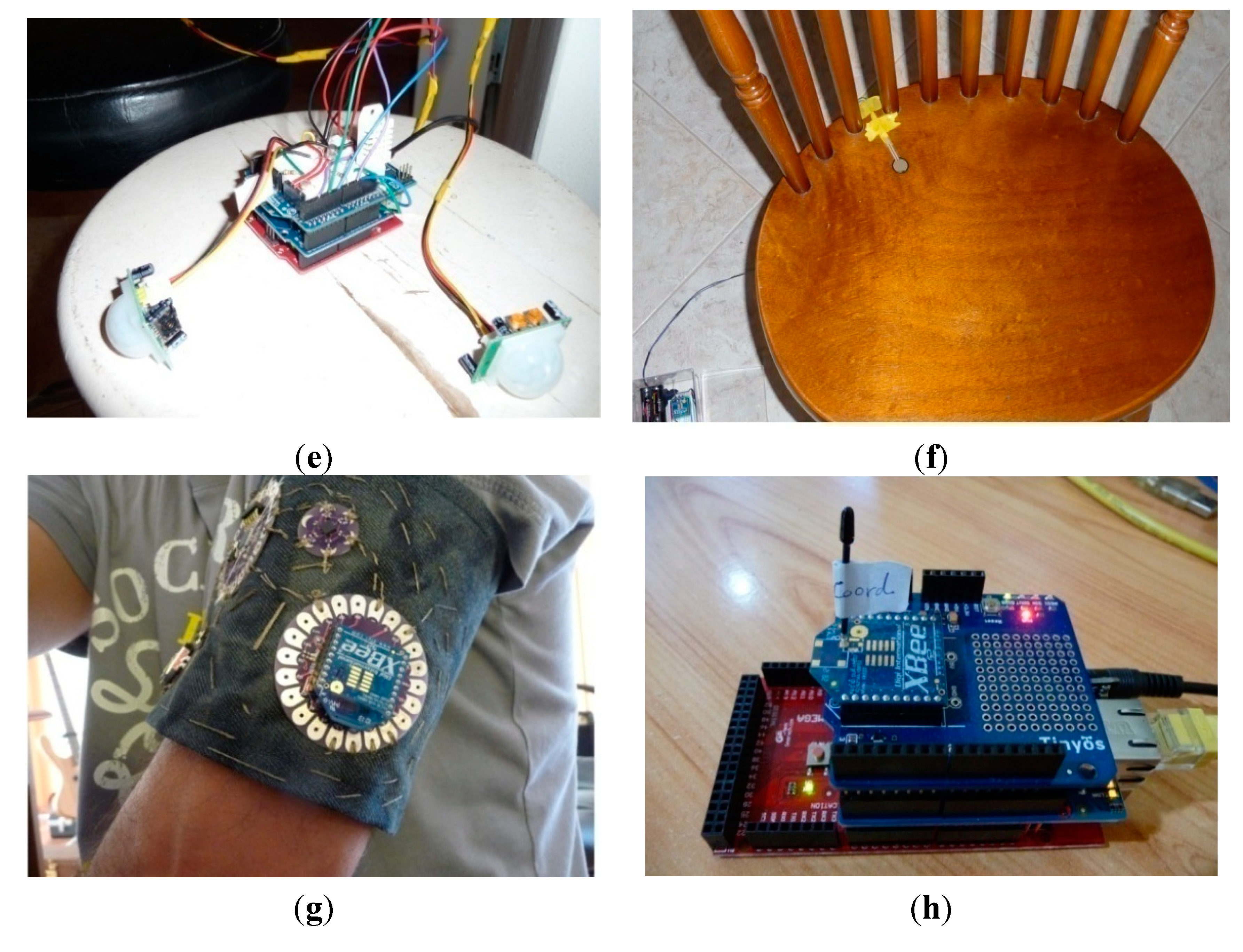

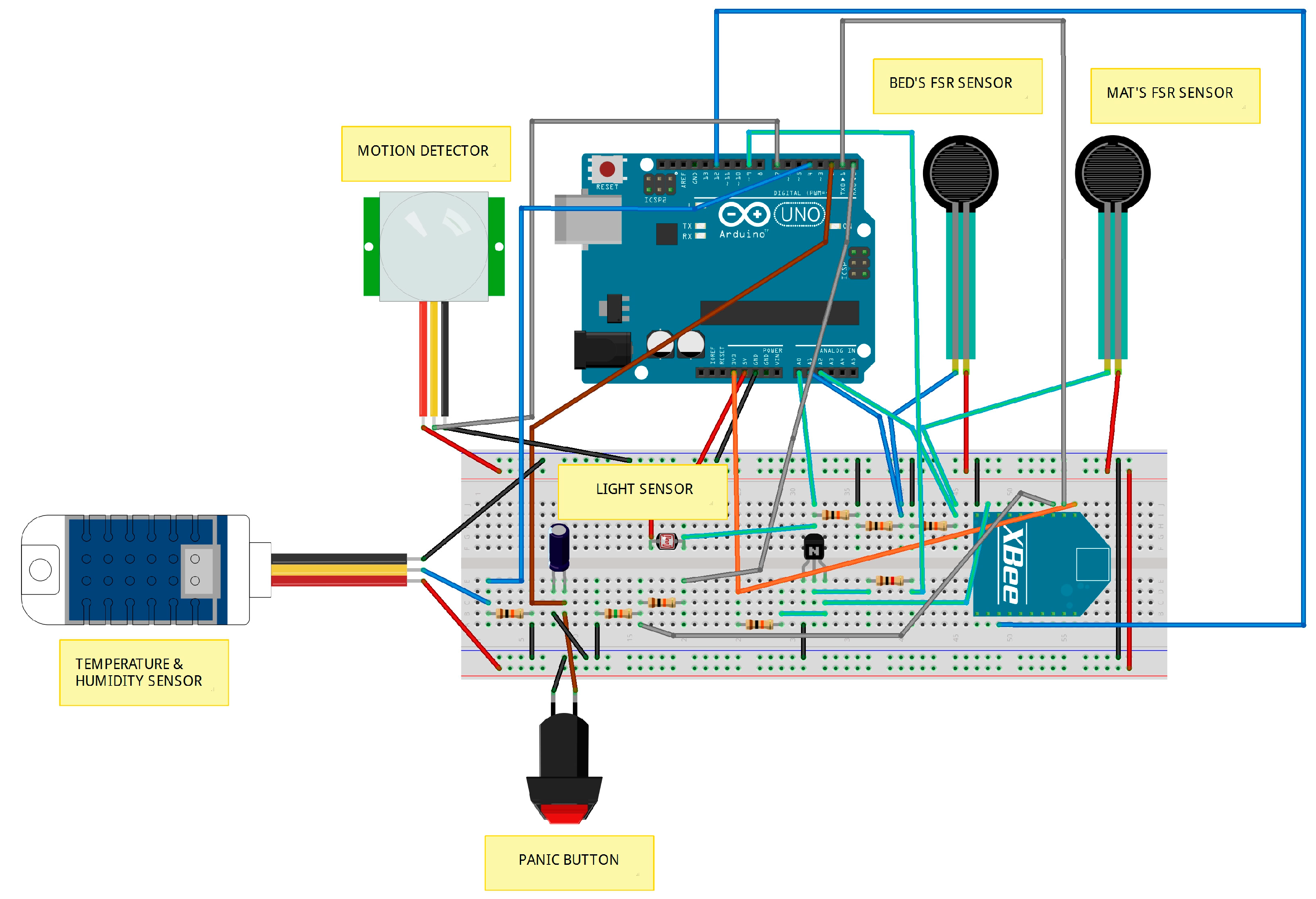

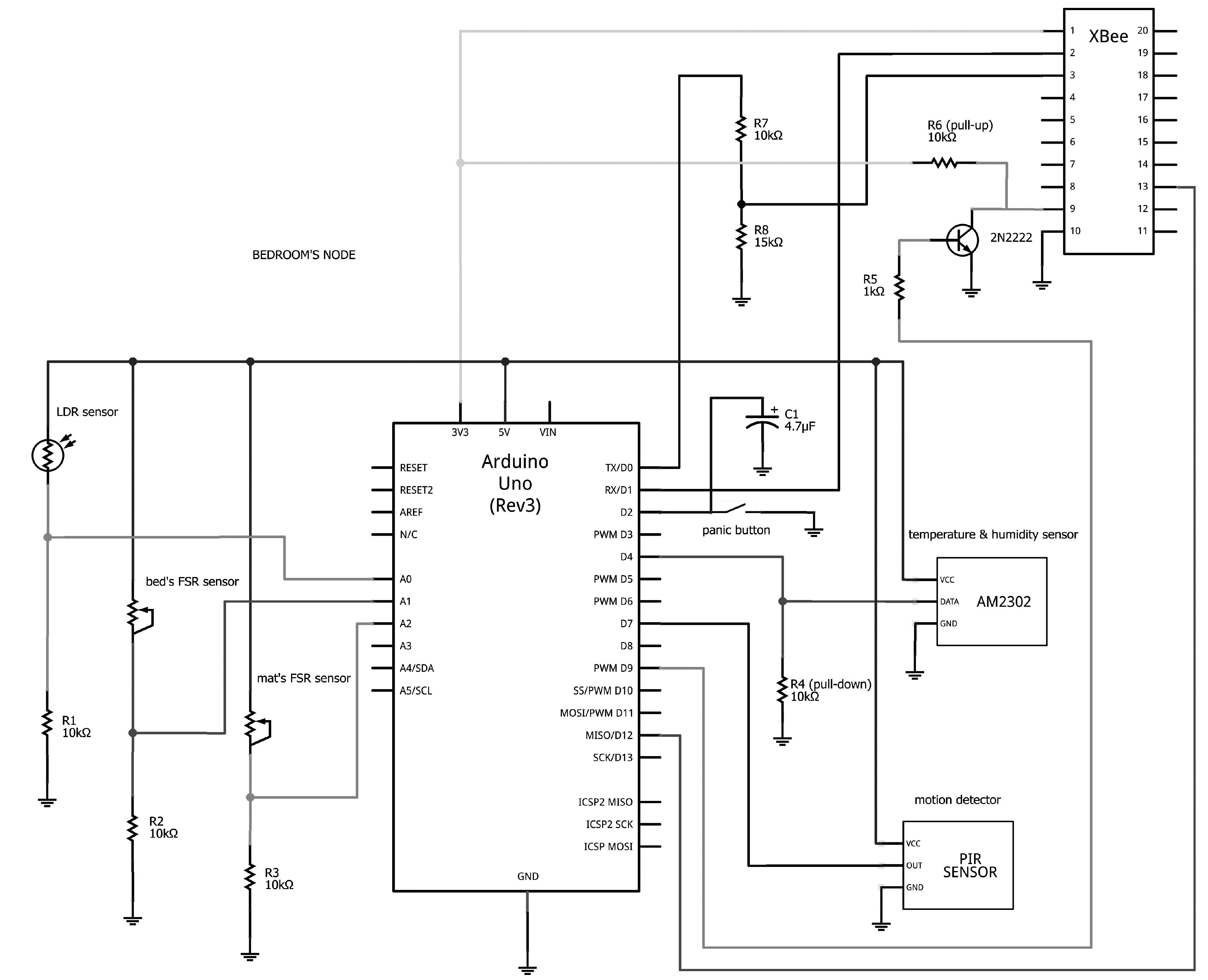

4.1. Hardware

4.2. Software

4.3. Energy Management Issues

4.3.1. Energy Management in Microcontroller Platforms

4.3.2. Energy Management in ZigBee (XBee) Modules

- Pin Hibernate (SM = 1), which minimizes the quiescent power (power consumed when in a state of rest or inactivity) at the expense of longer wake-up time (~13 ms). This mode is voltage level-activated; to wake up a sleeping module operating in Pin Hibernate mode, pin #9 should be de-asserted. This mode is appropriate to use when sleep transition is controlled by an external microcontroller (such as Arduino).

- Cyclic Sleep Remote (SM = 4), which allows modules to periodically check for RF data. In this mode, the module is configured to sleep and send a poll request to the coordinator at a specific interval set by the SP (Cyclic Sleep Period) parameter. The coordinator then transmits any queued data addressed to that specific module. The module returns to sleep mode in the case that it detects no radio activity for a period “Time Before Sleep” (ST). It is noted that this mode is more energy consuming for sleeping modules compared to the hibernate mode; however, the wakeup time is only 2 ms.

- Cyclic Sleep Mode with Pin Wake-up (SM = 5), which allows the wake up of a sleeping module either periodically or by the de-assertion of pin #9 for event-driven communications.

| Node | Sleep Mode | Time before Sleep | Cyclic Sleep Period | Number of Cycles to Power down IO | Sleep Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coordinator | SP = AF0 (28 s) | SN = FFFF (65.535) | |||

| bedroom | SM = 1 | ||||

| bathroom | SM = 1 | ||||

| kitchen | SM = 1 | ||||

| living room | SM = 1 | ||||

| armchair | SM = 5 | ST = 3E8 (1 s) | SP = 140 (3.2 s) | SN = 14 (20) | SO = 0 × 04 (extended sleep) |

| dining table chair | SM = 4 | ST = 3E8 (1 s) | SP = 140 (3.2 s) | SN = 14 (20) | SO = 0 × 04 (extended sleep) |

| actuator | SM = 4 | ST = 3E8 (1 s) | SP = 3E8 (10 s) | ||

| wearable | SM = 1 |

4.4. Privacy Issues

- On the network layer ZigBee implements: 128-bit AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) symmetric key encryption on packets payload, using a network key (NK); data integrity check through applying a hash function on packets’ header and data, using the NK; protection against replay attacks through using a 32-bits frame counter.

- On the application layer, ZigBee implements secure communication for the application data exchanged among two end devices, through applying an encryption key (link key, LK).

- The network key of the coordinator node has been set to NK = 0, so that a random network key will be selected. A ZigBee device can join the network subject to obtaining NK from the coordinator.

- The link key has been set to the same (arbitrary) value (ΚΥ > 0) on all devices (the coordinator and the end devices). Upon successfully joining the secure network, all application data transmissions will be encrypted by the (randomly chosen) network key. Since KY > 0, the network key is sent in encrypted form by the pre-configured link key (KY) when the devices join the network (When setting KY = 0 on all devices, the NK is sent unencrypted (“in the clear”) to joining devices. This approach introduces security vulnerability into the network and is not recommended.).

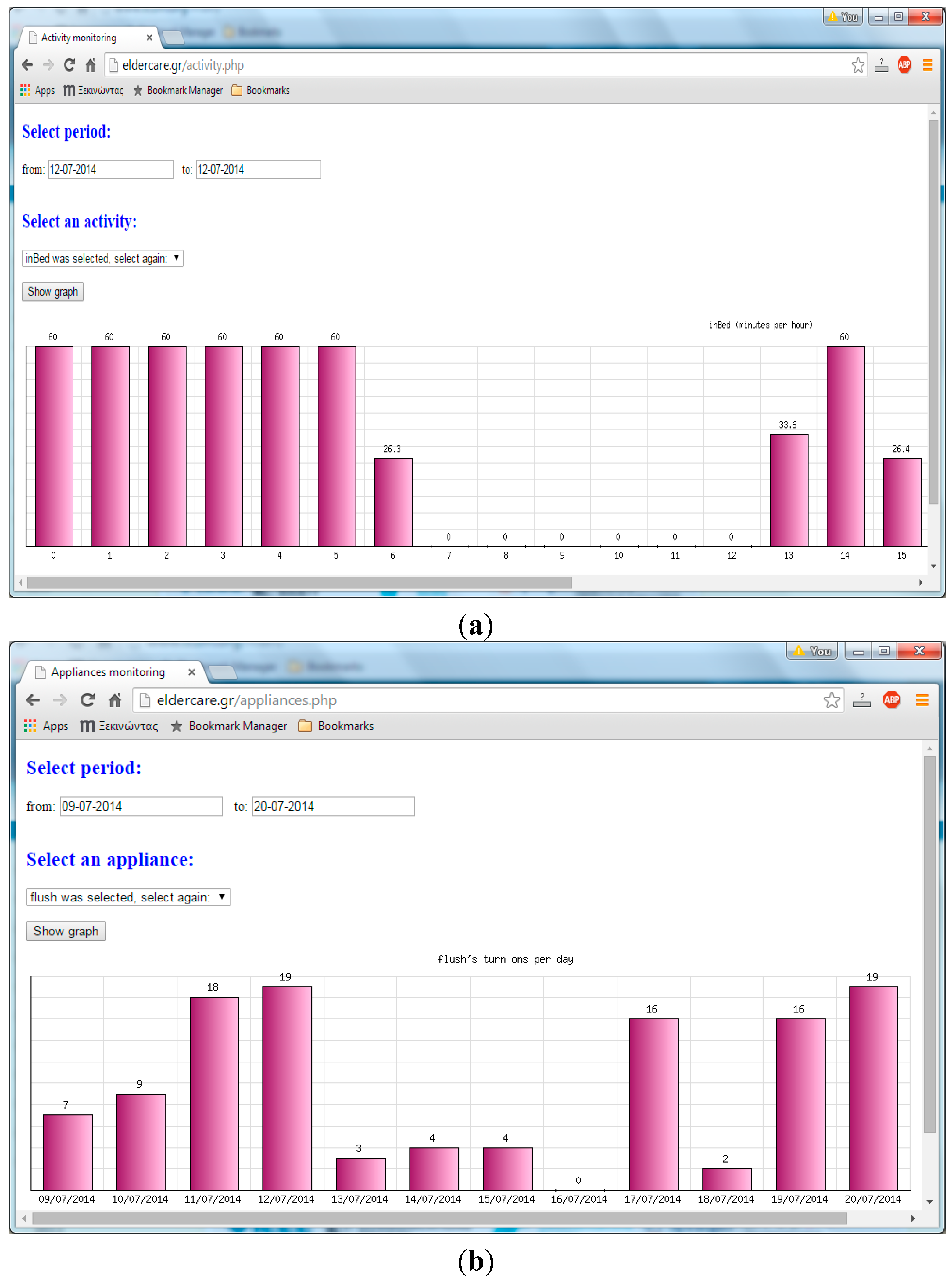

5. Real-Life Experiment and Lessons Learnt

- Occasionally, the wearable node incorrectly reported sudden movements as falls. Likewise, the node failed to detect slow falls on several tests. Addressing such inaccuracies is not straightforward [5] and requires: (a) thorough investigation as regards the optimal body position to place the node (e.g., hip or waist) [46]; (b) testing of different fall detection algorithms on several real ADL datasets; (c) mounting of additional sensors on the wearable node, such as gyroscope and altimeter.

- Moving events from one room to another have not been accurately detected in all occasions. In all probability, such inaccuracies could be addressed by using a larger number of motion detectors per room (e.g., covering different angles). Likewise, the force sensing resistor (FSR) sensors occasionally missed some events (lying on bed and stepping upon the mat next to bed), mainly when a subject lied on the edge of the bed or pressed the edge of the mat. Such problems could be easily tackled by using more than one FSR sensor to detect pressure activity.

- On rare occasions, events wherein the subject sat on the dining table chair or the arm chair and then shortly got up could be missed (provided that the events took place while the corresponding nodes were in sleep mode). However, this is not regarded as a problem, since this kind of events would be captured by decreasing the time the respective nodes remain in sleep mode, at the expense of increasing battery consumption.

- The choice of a suitable quantity and type of sensor for monitoring a certain activity is not straightforward (for instance, we have found that water flow sensors are not adequately reliable for detecting “turning on” events for taps), but requires careful investigation and thorough testing. This choice is dictated by a number of factors, such as cost, reliability, accuracy and installation effort.

- The necessity of using a microcontroller platform on a sensor board should be examined per case and could be determined by several factors, like: the need to perform some kind of information processing; the complexity/time associated with software development; the available budget for the node and the entire system; requirements related with the size, weight, energy efficiency and portability of the node.

- The considerable size of the Arduino-based nodes compromises the unobtrusiveness and discreteness of the overall deployment and demands extra effort and creativity to hide the boards and the accompanying wiring.

- To enable sophisticated activity inference on the spot and immediate triggering of actions on certain actuators, a relatively powerful host would be required (connected with the coordinator node via a LAN) as the Arduino MEGA would not have the capacity to support computationally challenging tasks.

6. Conclusions & Future Research

- Implement prototype extensions to cover other aspects of well-being surveillance, such as air quality monitoring to detect fire or high concentration of carbon monoxide or automated control of air quality/cleaning devices. Further, actuator nodes could be used to display reminders in the event of anomaly detection (e.g., to switch off the oven or to take medication).

- The deployment of real AAL systems engages substantial labor and financial investments; this highlights the increasing importance of simulations in AAL research [53,54]. Along this line, the use of AAL-tailored simulators would enable thorough experimentation with the architectural and technical elements of UbiCare under different application scenarios and environmental configurations.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rashidi, P.; Mihailidis, A. A survey on ambient-assisted living tools for older adults. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2013, 17, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadri, F. Ambient intelligence: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2011, 3, 36:1–36:66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.M.; Hansen, T.R.; Sprinkle, J.; Sastry, S. Information technology for Assisted Living at Home: Building a wireless infrastructure for assisted living. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual International Conference of the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (IEEE-EMBS’2005), Shanghai, China, 17–18 January 2005; pp. 3931–3934.

- Lymberopoulos, D.; Bamis, A.; Eixeira, T.; Savvides, A. BehaviorScope: Real-Time remote human monitoring using sensor networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Processing Sensor Networks, St. Louis, MO, USA, 22–24 April 2008; pp. 533–534.

- Putnam, M. Responding to Dangerous Accidents among the Elderly: A Fall Detection Device with Zigbee-Based Positioning. Master’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-C.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chou, Y.-C.; Kuo, I.T.; Huang, C.-N.; Chan, C.-T. Development of a fall detecting system for the elderly residents. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (ICBBE’2008), Shanghai, China, 16–18 May 2008; pp. 1359–1362.

- Nasution, A.H.; Emmanuel, S. Intelligent video surveillance for monitoring elderly in home environments. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP’2007), Crete, Greece, 1–3 October 2007; pp. 203–206.

- Zhongna, Z.; Wenqing, D.; Eggert, J.; Giger, J.T.; Keller, K.; Rantz, M.; Zhihai, H. A real-time system for in-home activity monitoring of elders. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC’2009), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–6 September 2009; pp. 6115–6118.

- Lu, C.-H.; Fu, L.-C. Robust location-aware activity recognition using wireless sensor network in an attentive home. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2009, 6, 598–609. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L. A pervasive and preventive healthcare solution for medication noncompliance and daily monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Applied Sciences in Biomedical and Communication Technologies (ISABEL’2009), Bratislava, Slovakia, 24–27 November 2009; pp. 1–6.

- Atallah, L.; Lo, B.; Yang, G.Z.; Siegemund, F. Wirelessly accessible sensor populations (WASP) for elderly care monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth’2008), Tampere, Finland, 30 January–1 February 2008; pp. 2–7.

- Dubowsky, S.; Genot, F.; Godding, S.; Kozono, H.; Skwersky, A.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.S. PAMM—A robotic aid to the elderly for mobility assistance and monitoring: A “helping-hand” for the elderly. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA’00), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2000; pp. 570–576.

- Vetere, F.; Davis, H.; Gibbs, M.; Howard, S. The Magic Box and Collage: Responding to the challenge of distributed intergenerational play. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2009, 67, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriansyah, A.; Dani, A.W. Design of small smart home system based on Arduino. In Proceedings of the Electrical Power, Electronics, Communications, Controls and Informatics Seminar (EECCIS’2014), Malang, Indonesia, 27–28 August 2014; pp. 121–125.

- Koo, B.; Park, Y.S.; Yang, S. Microcontroller implementation of rule-based inference system for smart home. Int. J. Smart Home 2014, 8, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Alemdar, H.; Ersoy, C. Wireless sensor networks for healthcare: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2688–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, P.; Cook, D.J. Keeping the resident in the loop: Adapting the smart home to the user. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern Part A Syst. Hum. 2009, 39, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Casas, R.; Falco, J.; Gracia, H.; Artigas, J.I.; Roy, A. Location-based services for elderly and disabled people. Comput. Commun. 2008, 31, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Nores, M.; Pazos-arias, J.; Garcia-Duque, J.; Blanco-Fernandez, Y. Monitoring medicine intake in the networked home: The iCabiNET solution. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Tampere, Finland, 30 January–1 February 2008; pp. 116–117.

- Wood, A.; Stankovic, J.A.; Virone, G.; Selavo, L.; He, Z.; Cao, Q.; Thao, D.; Wu, A.; Fang, L.; Stoleru, R.; et al. Context-Aware wireless sensor networks for assisted living and residential monitoring. IEEE Netw. 2008, 22, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Espinoza, P.; Aquino-Santos, R.; Cárdenas-Benítez, N.; Aguilar-Velasco, J.; Buenrostro-Segura, C.; Edwards-Block, A.; Medina-Cass, A. WiSPH: A wireless sensor network-based home care monitoring system. Sensors 2014, 14, 7096–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adami, A.M.; Pavel, M.; Hayes, T.L.; Singer, C.M. Detection of movement in bed using unobtrusive load cell sensors. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2010, 14, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipose, M.; Consolvo, S.; Fishkin, K.; Smith, P.I. Fast, detailed inference of diverse daily human activities. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp’2004), Nottingham, UK, 7–10 September 2004.

- Moshaddique, A.A.; Kyung-Sup, K. Social issues in wireless sensor networks with health care perspective. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2011, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Jin, H.; Ig-Jae, K.; Sang, C.A.; Hyoung-Gon, K. Activity recognition using wearable sensors for elder care. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Future Generation Communication Networks, Hainan Island, China, 13–15 December 2008; pp. 302–305.

- Ranjitha Pragnya, K.; Sri Harshini, G.; Krishna Chaitanya, J. Wireless home monitoring for senior citizens using ZigBee network. Adv. Electron. Electr. Eng. 2013, 3, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Suryadevara, N.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Wang, R.; Rayudu, R.K. Forecasting the behavior of an elderly using wireless sensors data in a smart home. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2013, 26, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.; Wagner, S.R.; Pedersen, C.F.; Beevi, F.H.A.; Hansen, F.O. Ambient Assisted Living healthcare frameworks, platforms, standards, and quality attributes. Sensors 2014, 14, 4312–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonhardt, S.; Kassel, S.; Randow, A.; Teich, T. Learning in the context of an ambient assisted living apartment: Including methods of serious gaming. In Proceedings of the China–Europe International Symposium on Software Engineering Education (CEISEE’2013), Milan, Italy, 13–14 May 2013; pp. 49–55.

- Garcia, N.M.; Rodrigues, J.J.P. Ambient Assisted Living; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, N.W.; Wallace, M.; Calia, E. Low cost prototyping system for sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 6th International Conference on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing (ISSNIP’2010), Brisbane, Australia, 7–10 December 2010; pp. 19–24.

- Pham, C. Communication performances of IEEE 802.15.4 wireless sensor motes for data-intensive applications: A comparison of WaspMote, Arduino MEGA, TelosB, MicaZ and iMote2 for image surveillance. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2014, 46, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelín-Jiménez, R.; López Villaseñor, M.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.A.; Ramos, R. WiSe-Nodes: A family of node prototypes for wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 5th IEEE International Conference on Systems and Networks Communications (ICSNC’2010), Nice, France, 22–27 August 2010; pp. 99–104.

- BeagleBone. Available online: http://beagleboard.org/bone (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Raspberry Pi. Available online: http://www.raspberrypi.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Nanode. Available online: http://www.nanode.eu/ (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Libelium Waspmote. Available online: http://www.libelium.com/ (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Arduino Language Reference. Available online: http://arduino.cc/en/reference/homePage (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Elderly monitoring website. Available online: http://eldercare.gr (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Bhatia, D.; Estevez, L.; Rao, S. Energy efficient contextual sensing for elderly care. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual IEEE International Conference on the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS’2007), Lyon, France, 23–26 August 2007; pp. 4052–4055.

- Narcoleptic. Available online: https://code.google.com/p/narcoleptic/ (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Zagler, W.L.; Panek, P.; Rauhala, M. Ambient Assisted Living systems-The conflicts between technology, acceptance, ethics and privacy. In Proceedings of Assisted Living Systems—Models, Architectures and Engineering Approaches, Dagstuhl, Germany, 14–17 November 2007.

- Davani, Z.A.; Manaf, A.A. A survey on key management of ZigBee network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Technologies and Business on the Web (EBW’2013), Bangkok, Thailand, 7–9 May 2013; pp. 74–78.

- Simplício, M.A.; Barreto, P.S.; Margi, C.B.; Carvalho, T.C. A survey on key management mechanisms for distributed wireless sensor networks. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2591–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digi INTERNATIONAL, XBee/XBee-PRO ZB RF Modules. Available online: http://www.adafruit.com/datasheets/XBee%20ZB%20User%20Manual.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Ogunduyile, O.O.; Zuva, K.; Randle, O.A.; Zuva, T. Ubiquitous healthcare monitoring system using integrated triaxial accelerometer, spo2 and location sensors. Int. J. UbiComp 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youtube. Experimental Setup of UbiCare. Available online: http://youtu.be/ogPEZW5rsN0 (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Youtube. Online Presence and Activity Monitoring in UbiCare. Available online: http://youtu.be/IbktK5lj5-8 (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Youtube. Triggering of a Fall Alarm in UbiCare. Available online: http://youtu.be/8F6czU7G-OU (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Youtube. Remote Controlling of the Actuator Node in UbiCare. Available online: http://youtu.be/Bzg3ATOF660 (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Fernández-de-Alba, J.M.; Fuentes-Fernández, R.; Pavón, J. Architecture for management and fusion of context information. Inf. Fusion 2015, 21, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, P.; Schmidt, A.; Otte, J.P.; Klein, M.; Rollwage, S.; König-Ries, B.; Dettborn, T.A. openAAL—The open source middleware for ambient-assisted living (AAL). In Proceedings of the AALIANCE Gabdulkhakova Conference, Malaga, Spain, 11–12 March 2010; pp. 1–5.

- Campillo-Sanchez, P.; Gómez-Sanz, J.J. Agent based simulation for creating Ambient Assisted Living solutions. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems (PAAMS’2014), Salamanca, Spain, 4–6 June 2014; pp. 319–322.

- Campillo-Sanchez, P.; Gómez-Sanz, J.J.; Botía, J.A. PHAT: Physical human activity tester. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference in Hybrid Artificial Intelligent Systems (HAIS’2013), Salamanca, Spain, 11–13 September 2013; pp. 41–50.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dasios, A.; Gavalas, D.; Pantziou, G.; Konstantopoulos, C. Hands-On Experiences in Deploying Cost-Effective Ambient-Assisted Living Systems. Sensors 2015, 15, 14487-14512. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150614487

Dasios A, Gavalas D, Pantziou G, Konstantopoulos C. Hands-On Experiences in Deploying Cost-Effective Ambient-Assisted Living Systems. Sensors. 2015; 15(6):14487-14512. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150614487

Chicago/Turabian StyleDasios, Athanasios, Damianos Gavalas, Grammati Pantziou, and Charalampos Konstantopoulos. 2015. "Hands-On Experiences in Deploying Cost-Effective Ambient-Assisted Living Systems" Sensors 15, no. 6: 14487-14512. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150614487

APA StyleDasios, A., Gavalas, D., Pantziou, G., & Konstantopoulos, C. (2015). Hands-On Experiences in Deploying Cost-Effective Ambient-Assisted Living Systems. Sensors, 15(6), 14487-14512. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150614487