Abstract

Electrostatic-driven microelectromechanical systems devices, in most cases, consist of couplings of such energy domains as electromechanics, optical electricity, thermoelectricity, and electromagnetism. Their nonlinear working state makes their analysis complex and complicated. This article introduces the physical model of pull-in voltage, dynamic characteristic analysis, air damping effect, reliability, numerical modeling method, and application of electrostatic-driven MEMS devices.

1. Introduction

Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) are an electromechanical integrated system where the feature size of components and the actuating range are within the micro-scale. Unlike traditional mechanical processing, manufacturing of MEMS device uses the semiconductor production process, which can be compatible with an integrated circuit, and includes surface micromachining and bulk micromachining. Due to the increasingly mature process technology, numerous sophisticated micro structural and functional modules are currently available. Therefore, greater optimized performance of the devices has been developed. Electrostatic-driven MEMS devices have advantages of rapid response, lower power consumption, and integrated circuit standard process compatibility. Among the present MEMS devices, many are electrostatic-driven MEMS devices, such as capacitive pressure sensors [1], comb drivers [2], micropumps [3], inkjet printer head [4], RF switches [5], and vacuum resonators [6].

Due to its simplicity of design and process, as well as convenience of integration with the integrated circuit processes to form a single-chip system, the electrostatic principle is commonly employed in sensing of MEMS or drive modules. However, due to the interaction between electrostatic force and structural behavior, namely the electromechanical coupling effects due to the coupling of multiple physical fields, such as stress fields and electrical fields, and since the system is nonlinear, instability of the pull-in often results, which leads to failures including stick, wear, dielectric changing, and breakdowns. Many studies have focused on common applications of electrostatic principle in MEMS devices, including: the instability when pull-in phenomenon occurs [7–37]; the deformation characteristic of microstructures subjected to electrostatic loads [18,38–41]; shape and position of drive electrodes [42–45]; dynamic response and optimization of electrostatic loads [46–57]; air damping effect [58–66], analysis method of chaos and bifurcation in electrostatic-driven systems [67,68], such as finite element method (FEM), finite difference method (FDM), and finite cloud meshless method (FCM) [68–73]; simulation software and systems of simulated dynamic behaviors, such as ANSYS, ABAQUS, COULOMB, MEMCAD, and macro models [69,72,74–78]; effects of routing parameters (voltage and temperature) on electrostatic force [79]; inherent nonlinear stiffness softening effect [70,80–82]; device reliability related failure modes and mechanisms; material selection; and reasonable design [8,32,38,83–92]. Without a thorough understanding of the effects of electrostatic force in MEMS systems, many practical phenomena, such as instability, nonlinearity and reliability, would have no scientific explanation. Thus, it is impossible to effectively explore and use the potential of MEMS technology. Under such circumstances, it is important and indispensable to study electro-mechanics of a micron scale structure under electrostatic loads.

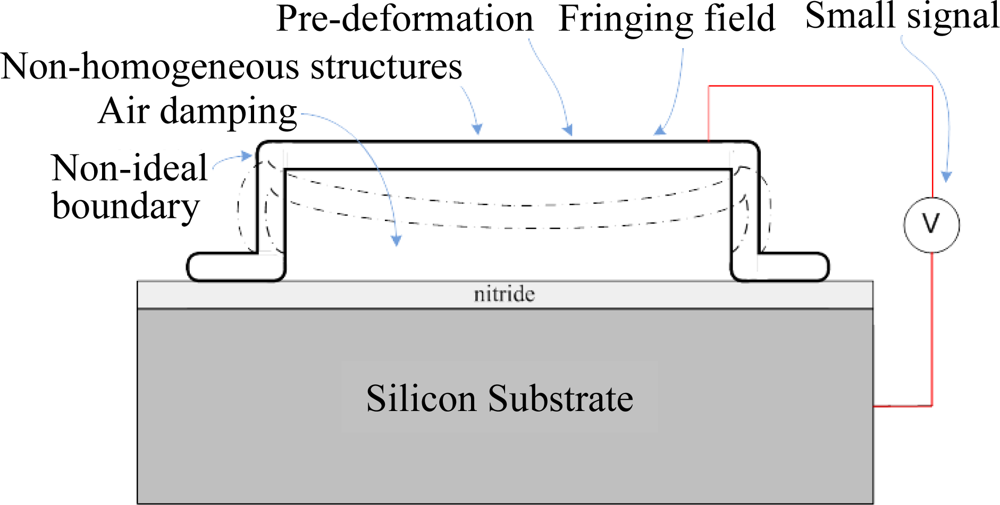

Accurate modeling the electrostatic microstructures is very challenging in virtue of the mechanical-electrical coupling effect and the nonlinearity of the structure and electrostatic force. Effects such as the non-ideal boundary conditions, fringing fields, pre-deformation due to the initial stresses, and non-homogeneous structures further complicate the modeling, as shown in Figure 1. A review paper [46] provided an overview of the fundamental research on nonlinear behaviors of electrostatic-driven microresonators, including direct and parametric resonances, parametric amplification, impacts, self-excited oscillations, and collective behaviors, such as localization and synchronization, which arise in coupled resonator arrays. Another review paper [56] presented an overview of the existing techniques before 2005 applied to the MEMS electrostatic actuation modeling and their dynamic behavior of the electromechanical system. A complete idealized model based on Euler-Bernoulli beam of an electrostatically actuated uniform beam is presented. Firstly, the energy expressions of the corresponding mechanical and electrical energy are derived. The kinetic energy and the bending and membrane strain energy are considered in the mechanical model. The fringing field is considered in the potential energy of electrostatic model. Two basic damping forces in MEMS, namely structural and viscous damping, are considered as well. The structural damping comes from the molecular interaction in the material due to deformation while the viscous damping comes from fluid that surrounds the moving microstructure. There are two types of viscous damping, namely couette flow damping and squeeze film camping. The governing equations are derived through substituting the above energy expressions into Lagrange equation. The static, transient, and oscillatory solutions of the model by numerical methods are illustrated respectively. A third review paper [57] presents an overview of the existing analytical models before 2007 for electrostatically actuated microdevices. General 3-dimensional nonlinear equations of motion for the coupled electromechanical fluid-structure interaction problem are outlined first. The microstructure is modeled as a solid elastic body. The air gap between the microstructure and fixed electrode is modeled as a homogeneous isotropic dielectric from the electric point of view while from the mechanical point of view, it is considered as a compressible Newtonian fluid. Deformations of microstructure are stated in Lagrange equation while the air gap and electrostatic field are stated in the Eulerian equations. The general 3-dimensional nonlinear model is too complicated to solve analytically. Therefore, simplified reduced order distributed models are illustrated along with such assumptions as beam and plate theories, squeeze film damping, and fringing field models.

Figure 1.

Nonlinear electromechanical coupling systems.

The aforementioned three review articles provide complete idealized models based on the assumptions of ideal fixed boundaries, homogeneous structures, and without pre-deformations, while this work provides models considering the non-ideal boundary conditions, non-homogeneous structures, and pre-deformations due to initial stresses. Over the past few decades’ development, MEMS technologies are now capable of manufacturing many microsensing or actuating components employing standard Complementary-Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor (CMOS) processes, which are the so-called CMOS-MEMS. There is a gap between prototype and commercial product that must be filled out, namely the reliability testing of MEMS devices. This is exactly what the aforementioned three review articles lack. The main benefit of CMOS-MEMS is batch production using the well-developed standard CMOS facilities. However, apart from the electrical testing of circuits, the MEMS-side still requires the mechanical testing of microsensing or actuating components. The performance of microdevices depends on the constitutive properties of the thin-film structural materials of which they are made. It is known that thin-film properties can differ from bulk material ones. As a result, certain material properties are critical in device performance, which must be monitored in manufacturing to ensure the repeatability from device to device and wafer to wafer. However, the mechanical property extraction methods available in the literature for MEMS fabrication require additional measurement and actuating equipments or complicated test structure designs, which are not compatible with standard CMOS metrology technologies. To be compatible with CMOS metrology technologies, the best choice of test and pickup signals are both electrical. In the past decade, the mechanical property extraction for MEMS by electrostatic structures was developed. The following sections present the quasi-static pull-in physical model of MEMS devices, dynamic response analysis of microstructures, air damping effects, breakdown mechanism analysis of the components, numerical simulation, and the application on inline mechanical properties extraction of microstructures.

2. Development of Related Studies on Electro-Mechanics for MEMS Devices

2.1. Physical Model of Quasi-Static Pull-in Voltage

As shown in Figure 1, when there is an electrical potential difference between the beam and substrate, namely the drive voltage, the electrostatic attractive force will attract the beam downward while the elastic restoring force of the beam, namely the spring force, will restore the beam upward. In brief, the electrostatic attractive force and the elastic restoring force are kept in an equilibrium state. However, the deformation of the beam would cause a distribution change in its surface charges; thus, the electric field would redistribute and rework on the beam until a new equilibrium state is achieved. Therefore, Figure 1 is a nonlinear electromechanical coupling system. Figure 2 shows the variations of electrostatic force and spring force versus to the deformation of the beam.

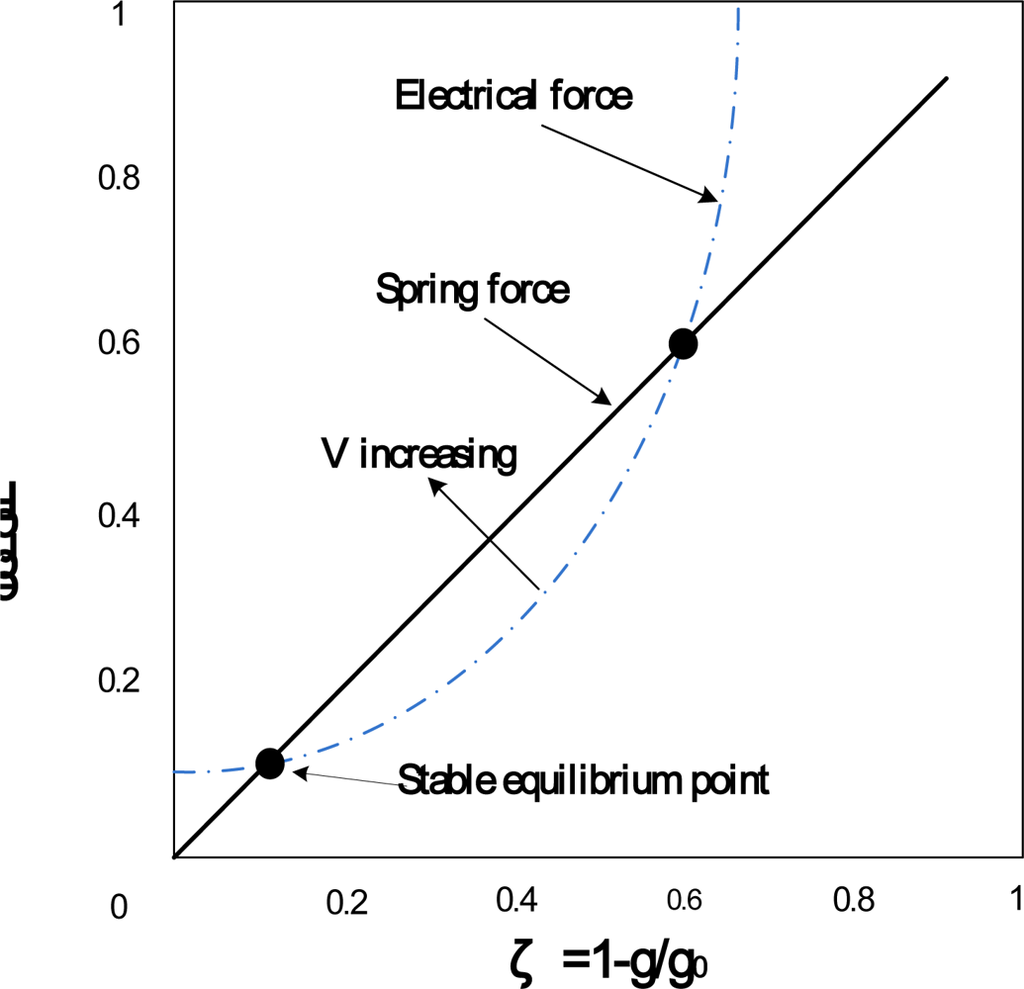

Figure 2.

The electrical and spring force for voltage-controlled parallel-plate electrostatic actuator [93].

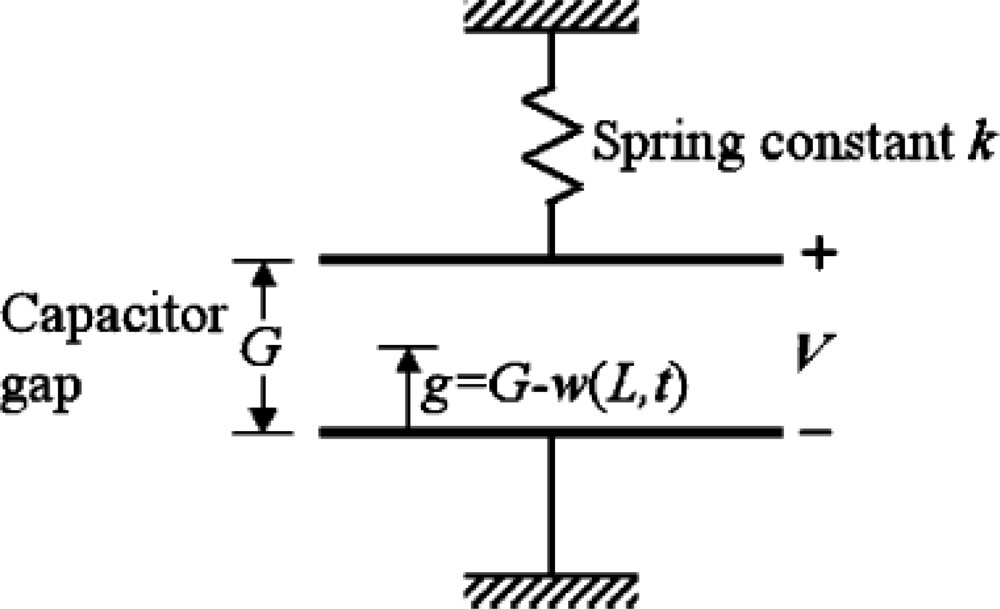

The abscissa is the ratio of the beam deformation (g0-g) to the initial gap (g0) between beam and substrate while the ordinate is the forces. The spring force is proportional to the deformation of beam while the electrostatic force, namely the electrical force, is proportional to the square of the deformation. When the drive voltage is weak, the spring force can contend with the electrostatic force and keep the system in a stable equilibrium state. However, when the drive voltage achieves a critical value, the spring force can no longer contend with the electrostatic fore and throws the beam off balance. The critical value of drive voltage is referred to as pull-in voltage. The system is under an unstable equilibrium state at pull-in. The physical model of Figure 1 can be modeled by the analytical model shown in Figure 3 which consists of a parallel-plate capacitor suspended by a spring. The pull-in occurs when the deformation exceeds the one third of the initial gap of the parallel-plate. Thus, the key of analyzing electro-mechanics for MEMS devices is the study of the quasi-static pull-in properties.

Figure 3.

A discrete model of an equivalent spring and a parallel-plate capacitor [80].

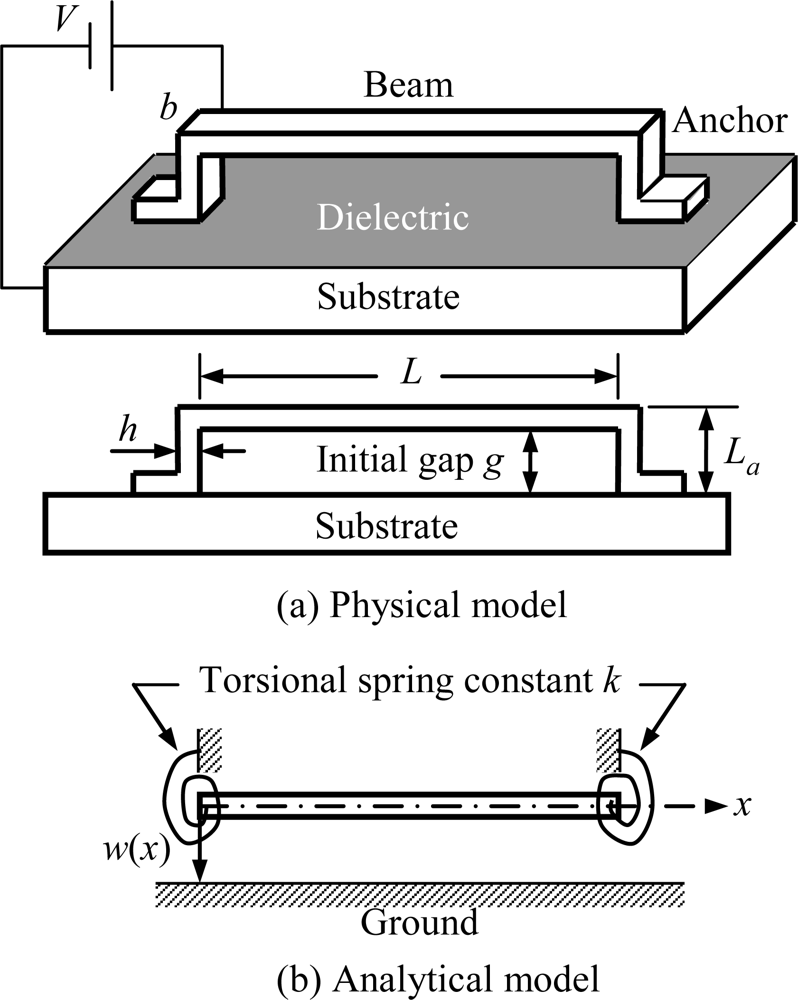

From 1994 to 1997 Senturia et al. published a series of research findings on electro-mechanics for MEMS devices. In 1994, Senturia [94] simulated a microbridge-shaped beam driven by electrostatic force as a lumped model of an equivalent spring and a parallel plate capacitor (Figure 3) in order to achieve the fundamental function forms of pull-in voltage, geometric dimension, and material parameters. Then in 1997, they proposed M-Test [8] technology, using semiconductor process technology to create three different micro test structures, namely, the microcantilever, the microbridge-shaped beam, and the microsector plate. They also produced micro- beams of different lengths to measure their pull-in voltage, respectively, in order to generalize the correcting factors based on those measured data and simulated numbers, and eventually modified the functional form based on the discrete model. In 2002, Pamidighantam et al. [19] simulated the system as a discrete system of an equivalent spring and a parallel plate capacitor. The stiffness of the equivalent spring and equivalent area of the parallel plate capacitor were obtained by CoventorWare, a commercial simulation software, in order to gain the pull-in voltage relation of the micro-bridge-shaped beams; however, the deviation was as high as 18%. In 2003, O’Mahony et al. [22] also analyzed the microbridge-shaped beams subjected to electrostatic loads using CoventorWare, and inferred the numerical solution of the microbridge-shaped beams by taking fringing capacitance effect, the efficiency of the plate-like phenomenon, and different boundaries into consideration. In 2005, Lishchynska et al. [95] derived the numerical solution of the pull-in voltage of cantilever beams, using the CoventorWare simulation software, and achieved an error within 4%. From 2004 to 2008, Krylov et al. published a series of research findings [7,12–14] on pull-in behavior of microstructures. In 2004, Krylov et al. [14] studied the transient nonlinear dynamics of microbeams subjected to electrostatic force, and developed a model based on the Galerkin procedure with normal modes which considered the effects about the distributed nonlinear electrostatic forces, nonlinear squeezed film damping, and rotational inertia of a mass carried by the beam. In 2006, Krylov et al. [13] developed simple expressions for electrostatic pressure with higher order corrections, mainly related to the curvature and slope of the electrode by using the perturbation theory. The results showed that tuning the ratio of the mechanical pressure, the string was with different pull-in behavior. In small initial pre-stress case, bistability of the string occurred. In 2008, Krylov et al. [7,12] reported on theoretical and experimental investigation of a multistability phenomenon in initially curved clamped-clamped microbeams subjected to a distributed electrostatic force. The results showed that the pull-in voltage of clamped-clamped with initially curved flexible was lower than a straight beam. From 2006 to 2009, Hu and co-workers proposed an approximate analytical model, taking into consideration such elements as initial stress, fringing capacitance effect, and elasticity boundaries [29,34,35,96,97]. For example, reference [34] presented an approximate analytical model to the pull-in voltage of a microbridge with elastic boundaries. The elasticity boundaries of the microbridge can be treated as a beam with torsional spring at both ends, and the conceptual diagram of a microbridge is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a) Physical model, (b) Analytical model [34].

The beam is with length L, anchor height La, width b, thickness h, and initial gap g, which subjected to a driving voltage V, resulted in a position-dependent deflection w(x). The equivalent torsional spring constant k can be expressed by the following equation [34]:

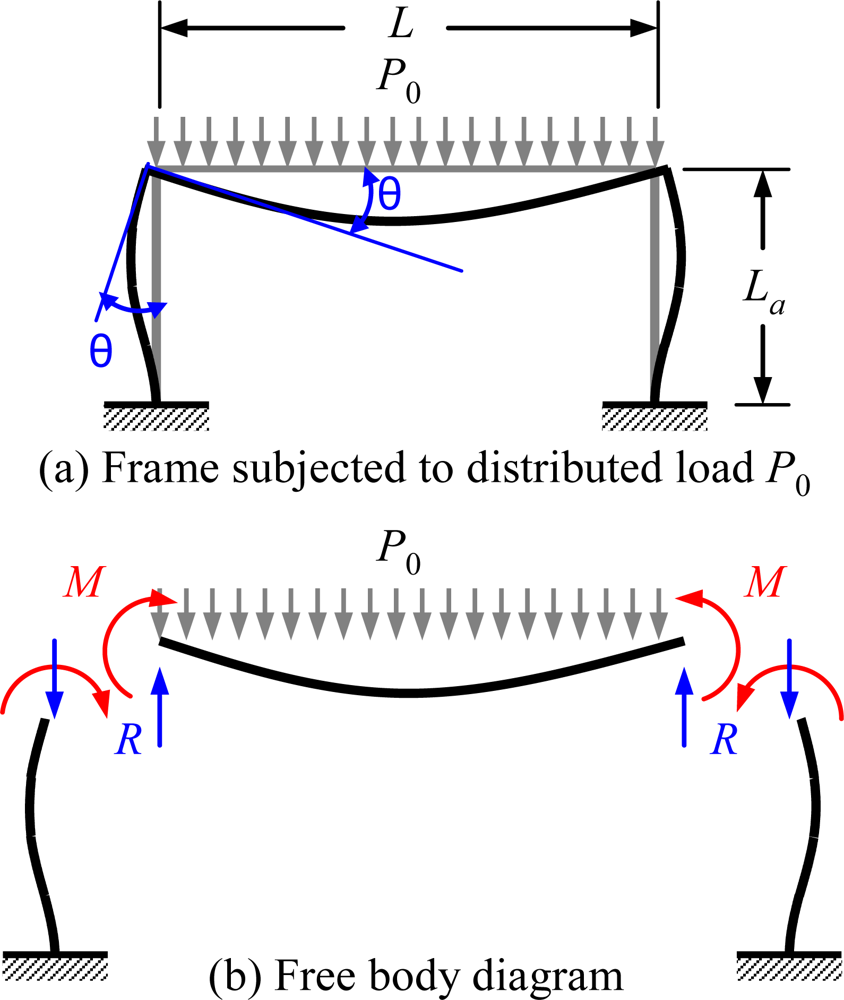

where I denoted the area moment of inertia, the subscript a denoted the anchor, and E denoted Young’s modulus. The reactive bending moment M, and the rotation angle θ were derived from a frame subjected to a uniform distributed load P0, as shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

(a) Frame subjected to distributed load P0, (b) Free body diagram [34].

Based on the Euler’s beam model and minimum energy method, the pull-in voltage VPI of a micro-bridge was [34]:

where σ0 denoted the initial stress, and ϕ was first natural mode of a beam having torsional spring at both ends given by [132]:

Besides, β should satisfie the following equation:

Equation (4) shows an obvious physical meaning. The first term shows that the pull-in voltage was dependent on initial residual stress, the second one was dependent on beam flexibility, and the third one was dependent on elastic boundary condition. The findings had greater physical significance than the previous studies we motioned above, which employed numerical methods in studies of electro-mechanics for MEMS Devices.

2.2. Microstructure Dynamic Response Analysis

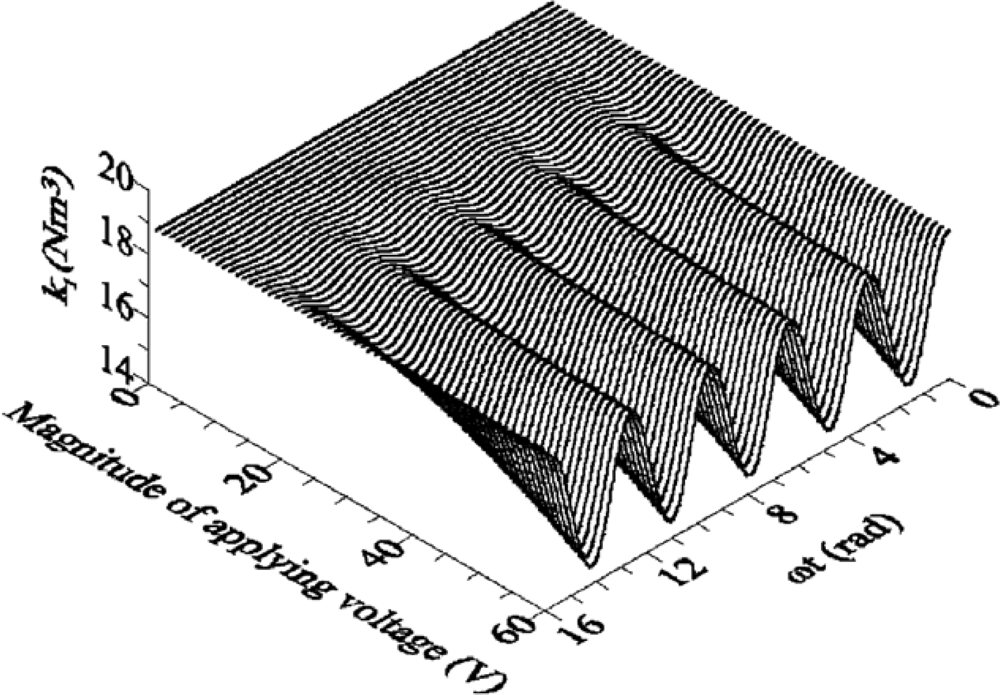

In the movement process, beams are affected by the interaction between electrostatic force, elasticity-restoring force, and damping force. As a result, the equation of motion in coupling is often a simultaneous partial differential equation of an electrostatic force equation, an Euler beam equation, and an air-damping equation, which explain the dynamic actions of the devices in all three spatial dimensions. It would be very difficult to solve this equation using only a numerical method. Therefore, mathematical operations, such as state-variable analysis and basic function expansion methods, are usually employed to translate a partial differential equation of infinite dimensions into a system of ordinary differential equations of finite dimensions. This is known as the reduced order method [75,98]. Younis et al. [75] presented a reduced-order model to analyze the behavior of microbeams actuated by electrostatic force. The model was obtained by discretizing the distributed-parameter system using Galerkin procedure into a finite-degree-of-freedom system, which considered the effects about moderately large deflections, dynamic loads, linear and nonlinear elastic restoring forces, the nonlinear electrostatic force generated by the capacitors, and the coupling between the mechanical and electrostatic force. However, under the reduced order method, it would be very difficult to analyze the dynamic actions of the devices when air damping is taken into consideration; while other related parameters are still obtained through the numerical method, thus, analysis efficiency has not been improved. To solve this problem, Clark [99] determined an effective method for analyzing the dynamic actions of MEMS devices, by which the complicated system is divided into several basic structural units, and then the equivalent circuit model, consisting of those basic structures, is built using the simulation protocols between similar systems. Wen [100] employed a model analysis method based on linear disposal near the bias point in order to analyze the AC small signal in frequency domain of beams. Zhang [101] set an electrostatic-driven cantilever beam equivalent to a single-degree-of-freedom model to conduct its analytical form, and used a feedback mechanism to realize the coupling. Time and frequency domain analyses were conducted. In the time domain analysis, stronger driving voltage leads to more obvious beams overshoot. In the frequency domain analysis, the natural frequency of the cantilever beams would gradually reduce with an increase of voltage. Hu [80] established an analysis model for dynamic characteristics and stability of electrostatic-driven devices, and found that the stiffness of a microstructure will be softened periodically with the frequency of applied voltage. The variation of stiffness increases with the magnitude of applied voltage (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The first modal stiffness variation [80].

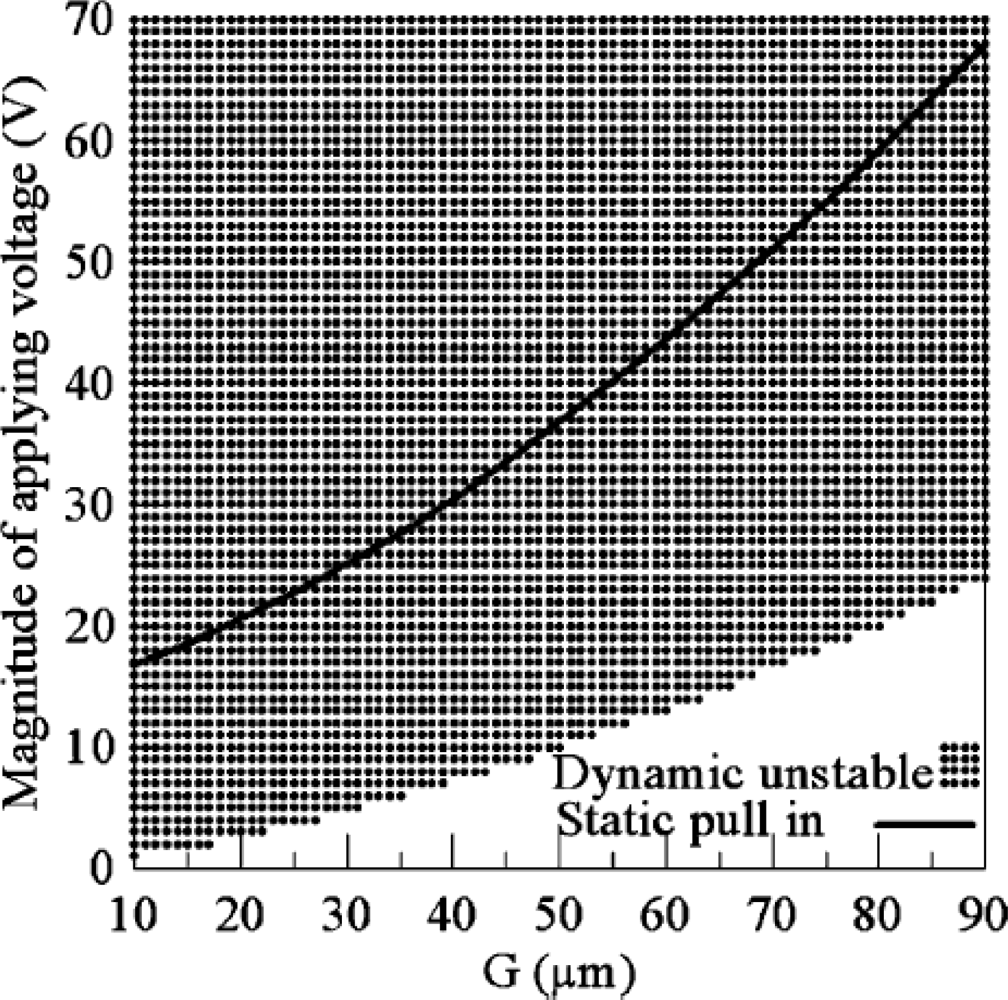

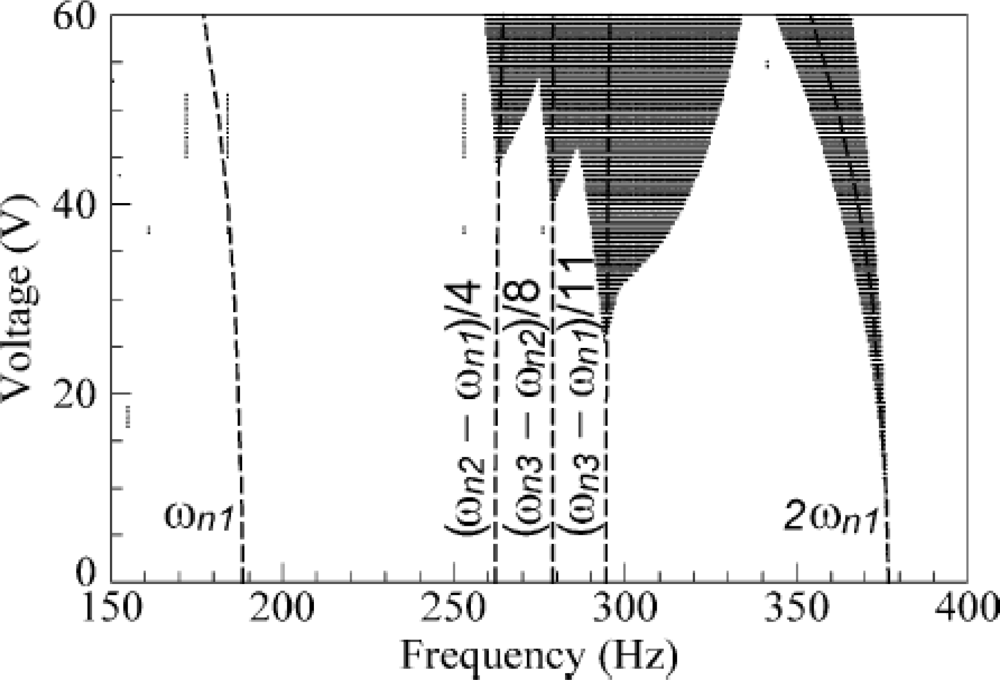

The dynamical pull-in voltage may be lower than the static one (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Comparison between dynamic instability and static pull-in [80].

Furthermore, the instable regions of the dynamical pull-in expand with the increasing of applied voltage, as shown in the dot-area of Figure 8. If the structure acts in small deformation condition, the beam can be considered as linear. On the contrary, for large deformations, non-linear structural effects have to be considered. For solving the non-linearity problem, one can use the finite element analysis (FEA) to obtain a non-linear cubic term. Moreover, it would be helpful to predict non-linear mechanical stiffness behavior [71,72,102,103]. The governing equation of a vibrating system with cubic stiffness non-linearity can be written as [50]:

where c, f(v), m, k1, k3, and x represent the equivalent damping coefficient, the equivalent external periodical force depending on drive voltage v, the equivalent mass, the equivalent linear stiffness coefficient, the equivalent non-linear stiffness coefficient, and the deformation respectively.

Figure 8.

Dynamical instable region of a microcantilever subjected to an AC voltage [80].

2.3. Air Damping Effect

Microstructures, which move relatively along a vertical direction, are widely used in MEMS devices, such as microaccelerometers [104,105]. During movement, the structure would be affected by the air damping between device and substrates. When the devices are in greater working amplitude vibration, the air damping force would be obviously strengthened. Thus, it is critical to establish an air damping model of components under movement. Blech [63] analyzed seismic accelerometers, and treated them as a damping device consisting of two plates with squeeze film of gas between them. Besides, the squeeze film damping cutoff frequencies can be solved analytically from the lowest eigenvalue of the Helmholtz equation. Andrews [106] employed the theoretical model to predict the frequency response of isolated rectangular plates oscillating normal to each other and the prediction results agreed well with the experimental data. Darling [107] presented an analytical method based upon a Green’s function solution to linearize Reynolds equation, and allowed the forces from compressible squeeze film damping to be rapidly calculated for arbitrary acoustic venting conditions along the edges of a moveable structure. For laminar flows under relatively high pressure or relatively large space between the plates, Reynolds equations are used for analysis. The air flow can be treated as a continuum media. The degree of rarefaction depends on the so-called Knudsen number, Kn, defined as [108], where d is the gap distance and l the mean-free-path:

Veijola [59] utilized the circuit model to calculate the effective viscosity in a narrow gap between the moving surfaces. The damping coefficient was obtained by using Blech model [63], and the spring constant was estimated by curve fitting experimental measurements. Besides, he used an effective coefficient ηeff of viscosity for accounting for the slip-flow condition, where η0 is the coefficient of viscosity under atmospheric pressure:

In 1999, Li et al. [109] studied the damping effects of beams in a resonance state. In 2001, Yang [110] analyzed the relation between the air damping effects of MEMS devices and their working efficiency. In 2005, Zhang[70] suggested a simplified electrostatic-driven cantilever beam model, which considers nonlinear air damping and could be used to study the relationship between resonance response parameters and nonlinear dynamics. In the same year, Wang [60], took squeezed gas effects into consideration, and established an air damping model of a microplate structure in order to obtain a characteristic change of a pressed film within a resonance pressed cycle of motion through the finite difference method. The study showed that squeezed air effects must be taken into consideration in a theoretical analysis model; otherwise, the air damping effects would be over measured. The increased plate dimension of microstructures would increase the damping force, and the increasing speed of damping force is greater than that of the size of the microstructures. In addition, the increased resonance frequency would increase the air damping effect. In 2007, Wang [111] further established a nonlinear dynamics model of a microresonator by taking slip boundaries and squeezed air effects into consideration. Also in 2007, Zhu [112] developed an analytical formula of air damping force and the damping coefficient of a microplate structure by converting the governing equation along a vertical direction into the Fourier series. The study showed that the air damping coefficient is inversely proportional to the third power of the thickness of the air gap between the two plates.

2.4. Numerical/CAD Methods

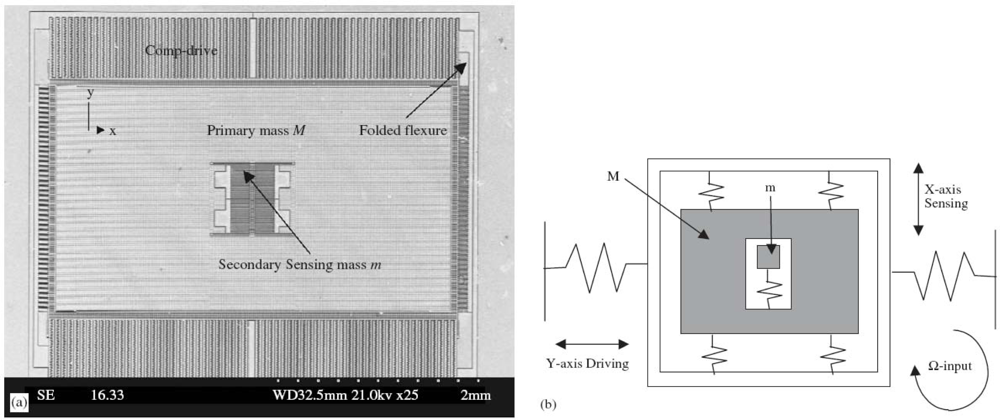

The development process of a MEMS system is complicated, involving product design, manufacturing, packing and systemic integration. Like an IC circuit and its common mechanical structures, MEMS devices can use computer aided design (CAD) to facilitate their performance, reliability, reduce the development cycle and costs. The main difference is that MEMS CAD is still a work in progress. For electronic products design, the technology of electronic design automation (EDA) serves as a platform to enable circuit designers to design and analyze, with the help of a computer and model libraries provided by foundries and related design kits, in order to complete the design, development, and testing of devices in the most economic and efficient method. SPICE, SABER, and Simulink are software commonly used. For mechanical products design, MDA (Mechanical Design Automation) has numerous and large-scale common software to aid design, manufacturing, and analysis, such as IDEAS, UGII, and ProPEngineer. A linking device between EDA and MDA is required for MEMS CAD to determine multiple physical coupling effects, which increases the development difficulties of MEMS CAD. Numerical simulation of MEMS devices mainly uses numerical methods, such as the finite element method, the boundary element method, and can simulate the actions of various structural components with high accuracy. Its drawbacks are high computation complexity and low analysis efficiency. Therefore, related studies have explored how to reduce the large amount of computations. Hung [113] examined the methods to define grids, which are able to generate the most effective reduced model during the process of devices’ working. Stewart [114] developed a set of simulation methods, which can be used for microstructures in small vibraction situation. Swart [115] invented a computer-aided software, named AutoMM, which can automatically produce dynamic models for microstructures. Commercial FEA/BEA tools usually used for the MEMS design, like ANSYS, ABAQUS, Maxwell, CoventorWare, CFDRC, IntelliCAD, CAEMEMS, SESES ,and SOLIDIS. For example, Figure 9 shows the SEM of a gyroscope and its lumped model.

Figure 9.

SEM of a gyroscope (a) and its lumped model (b) [50].

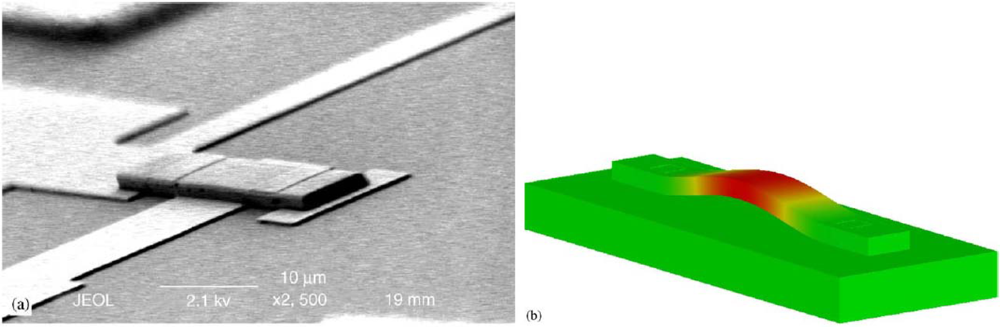

The suspended MEMS devices can always be treated as linear lumped model under the assumption of small displacement. The whole structure can be considered as linear massless springs (flexures parts) connected to the rigid mass (the proof mass).Then, one can use the FEA tools to obtain the spring constants and the equivalent mass [118]. Besides, one can use these tools to solve the governing equations with given boundary conditions to know the mode shape of microstructures (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

SEM of a microbeam resonator (a) and its 1st modal shape simulated by CoventorWare (b) [50].

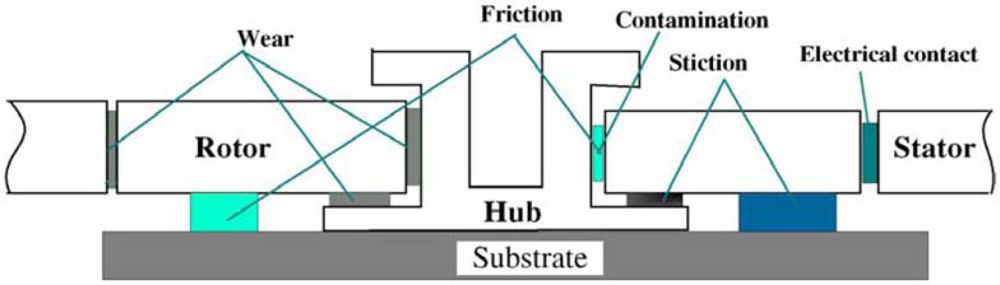

2.5. Breakdown Mechanism Analysis of Microstructures

The breakdown of MEMS devices means that the devices are unable to achieve their expected functions. Zhang [117] discussed major breakdown modes and breakdown mechanisms of various MEMS devices, such as microswitches, micromotors, and comb drivers [118–124]. Mariani [87–92] studied the breakdown mechanism of multi-scale structures subjected to drop impacts using a finite element method. Komvopoulos [125] proposed that the major breakdown modes of MEMS devices are friction, wear, and stick (Figure 11), which should be avoided to improve the reliability of the devices.

Figure 11.

Tribology issues during micromotor operation [38].

In 1992, Bart [126] proposed a dynamic model that involved analysis of kinetic friction, and found that the roughness of the surface has great impact on the friction force of the devices. Tai [127] established a model for friction movement to calculate the static friction coefficient of the devices, and suggested that due to the narrow gap between the rotor and the hub, contact wear is easily produced. Gabriel [122] found that the hub would be dramatically corroded or deformed at high speeds as the wear shortens the life span of the devices and limits their performance; however, a bracing structure could be adopted to avoid wear. Stick between the contact faces could prevent the devices from repeated operation or even working. Spengen [118] reported that the surface roughness of devices is a critical element that affects stick. Ren et al. [128] employed self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) to reduce the stick of devices surfaces.

3. Extracting the Mechanical Properties Utilizing Electromechanical Behavior of the Microstructures

Electrostatic-driven MEMS devices have been widely used in various sensing and actuating, and can be used in biosensors or to extract mechanical properties of thin film materials. In the past decade, all the important discoveries on the technology of calculated mechanical properties of thin film materials came from the research team of Senturia [8] at MIT. The key point is to generalize the threshold voltage of devices and the experimental formula of MEMS mechanical properties. The advantage of this technology is the simplicity of the measurement of the threshold voltage; while the disadvantage is that the experimental formula must be used in conjunction with certain test micro structures. If the devices changes, then the formula has to change as well. It is also difficult to use the experimental formula in non-ideal boundaries, such as with pre-deformation or non-homogenous sections. Different from Senturia, Hu [29,30,34,35,96,97,129–131] proposed a nonlinear mechanical and electrical coupling system of a micro structure for a pull-in voltage approximate analytical model, which involves non-ideal boundaries, fringing capacitance effect, and residual stresses. Hu also developed a fully electrical signal testing method for the measurement of the mechanical properties of thin film materials, which can be used in wafer-level tests to examine the Young’s modulus and residual stresses of micro structures. Reference [131] presented a formula about the relationship between Young’s modulus, residual stress and pull-in voltage of micro test beams which considered the effects about fringing field capacitance, the distributed characteristics of micro test beams, and the electromechanical coupling effect:

where ηPI denoted the value of η at pull-in state which can be expressed as:

Equation (12) can be solved by numerical method. Substituting the value of ηPI into equation (11), than we can obtain to the correlation between the pull-in voltage VPI and the structural material parameters σ0 and E:

where the parameters S and B depend on the geometrical parameters of micro test beam and are given as:

where b, E, h, I, L, and σ0 represent the beam width, Young’s modulus, thickness, area inertia moment of beam cross section, beam length, and the initial stress, and ϕ was first natural mode of a fixed-fixed beam given by [132]. Therefore, one can extract Young’s modulus and residual stress easily by substituting the measured pull-in voltages of the two test beams with different length:

The testing technology is able to conduct inline measurements and monitoring of wafer fabrication, and uses existing semiconductor measurement equipment, as they are adequate for semiconductor and MEMS processes.

4. Conclusions

Analysis of the electro-mechanics of electrostatic-driven MEMS devices is complex due to the coupling of several energy domains. Besides, the electromechanical coupling effects will cause the pull-in instability, nonlinear response, reliability issues during the system operation. This article has reviewed related literature on electrostatic-driven MEMS devices, including a physical model of quasi-static pull-in voltage about how the physical quantities, like residual stress, elastic boundary, structural flexibility, fringing field capacitance to affect pull-in voltage, dynamic characteristic analysis about the dynamic behavior when system operates, air damping effects about the relation between air damping coefficient and geometry of structure, reliability about the failure mode and failure mechanisms of various devices, numerical modeling method about how to generate the most effective reduced model to fit the real system, and application. By the further understanding of the interaction mechanisms of these significant topics, it is helpful for developing the optimization techniques and applications in MEMS field.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the financial support of our research from the National Science Council of Taiwan through the Grant No. 97-2221-E-002-151-MY3 and NSC-98-3111-Y-076-011. Figures 2, 6–8 are reproduced by permission of Sensors and Actuators, A.; Figures 3 and 4 are reproduced from Journal of Micromechanical and Microengineering; Figures 9–10 reproduced by permission of Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing; Figures 11 was reproduced by permission of Microelectronics Reliability.

References

- Akar, O.; Akin, T.; Najafi, K. A wireless batch sealed absolute capacitive pressure sensor. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2001, 95, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schonhardt, S.; Korvink, J.G.; Mohr, J.; Hollenbach, U.; Wallrabe, U. Optimization of an electromagnetic comb drive actuator. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2009, 154, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, L.S.; Kan, W.H.; Chen, M.K.; Chou, Y.M. Parameter extraction from BVD electrical model of PZT actuator of micropumps using time-domain measurement technique. Microfluid. Nanofluid 2009, 7, 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Kamisuki, S.; Fujii, M.; Takekoshi, T.; Tezuka, C.; Atobe, M. A high resolution, electrostatically-driven commercial inkjet head. Proceedings of the IEEE Thirteenth Annual International Conference on MEMS, Miyazaki, Japan, 23–27 January 2000; pp. 793–798.

- Nguyen, C.T.C.; Katehi, L.P.B.; Rebeiz, G.M. Micromachined devices for wireless communications. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 1756–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Tilmans, H.A.C.; Legtenberg, R.; Schurer, H.; Ijntema, D.J.; Elwenspoek, M.; Fluitman, J.H.J. (Electro-) mechanical characteristics of electrostatically driven vacuum encapsulated polysilicon resonators. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 1994, 41, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Krylov, S. The pull-in behavior of electrostatically actuated bistable microstructures. J. Micromech. Microeng 2008, 18, 055026. [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg, P.M.; Senturia, S.D. M-TEST: A test chip for MEMS material property measurement using electrostatically actuated test structures. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1997, 6, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Castaner, L.M.; Senturia, S.D. Speed-energy optimization of electrostatic actuators based on pull-in. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1999, 8, 290–298. [Google Scholar]

- Castaner, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Pons, J.; Senturia, S.D. Pull-in time-energy product of electrostatic actuators: Comparison of experiments with simulation. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2000, 83, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fargas-Marques, A. Resonant pull-in condition in parallel-plate electrostatic actuators. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2007, 16, 1044. [Google Scholar]

- Krylov, S.; Seretensky, S.; Schreiber, D. Pull-in behavior and multistability of a curved microbeam actuated by a distributed electrostatic force. Proceedings of MEMS 2008: The 21st IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical System, Tucson, AZ, USA, 13–17 January 2008; pp. 499–502.

- Krylov, S. Higher order correction of electrostatic pressure and its influence on the pull-in behavior of microstructures. J. Micromech. Microeng 2006, 16, 1382. [Google Scholar]

- Krylov, S.; Maimon, R. Pull-in dynamics of an elastic beam actuated by continuously distributed electrostatic force. J. Vibr. Acoust. Trans. ASME 2004, 126, 332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, L. New methods for measuring mechanical properties of thin films in micromachining: beam pull-in voltage method and long beam deflection (LBD) method. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1995, 48, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Degani, O.; Socher, E.; Lipson, A.; Leitner, T.; Setter, D.J.; Kaldor, S.; Nemirovsky, Y. Pull-in study of an electrostatic torsion microactuator. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1998, 7, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Degani, O.; Nemirovsky, Y. Design considerations of rectangular electrostatic torsion actuators based on new analytical pull-in expressions. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2002, 11, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Guardia, R.; Dehe, A.; Aigner, R.; Castaner, L.M. Current drive methods to extend the range of travel of electrostatic microactuators beyond the voltage pull-in point. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2002, 11, 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Pamidighantam, S.; Puers, R.; Baert, K.; Tilmans, H.A.C. Pull-in voltage analysis of electrostatically actuated beam structures with fixed-fixed and fixed-free end conditions. J. Micromech. Microeng 2002, 12, 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.C.; Mohammad, A.B.; Kassim, N.M. Analytical modeling for determination of pull-in voltage for an electrostatic actuated MEMS cantilever beam. Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Sydney, Australia, June 2002; pp. 233–238.

- Xiao, Z.; Peng, W.; Wu, X.; Farmer, K.R. Pull-in study for round double-gimbaled electrostatic torsion actuators. J. Micromech. Microeng 2002, 12, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, C.; Hill, M.; Duane, R.; Mathewson, A. Analysis of electromechanical boundary effects on the pull-in of micromachined fixed-fixed beams. J. Micromech. Microeng 2003, 13, S75–S80. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Zhe, J.; Wu, X. Analytical and finite element model pull-in study of rigid and deformable electrostatic microactuators. J. Micromech. Microeng 2004, 14, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Miller, W.C. A closed-form model for the pull-in voltage of electrostatically actuated cantilever beams. J. Micromech. Microeng 2005, 15, 756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, P.C.P.; Chiu, C.W.; Tsai, C.Y. A novel method to predict the pull-in voltage in a closed form for micro-plates actuated by a distributed electrostatic force. J. Micromech. Microeng 2006, 16, 986–998. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Miller, W.C. Pull-in voltage study of electrostatically actuated fixed-fixed beams using a VLSI on-chip interconnect capacitance model. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2006, 15, 639–651. [Google Scholar]

- Elata, D.; Bamberger, H. On the dynamic pull-in of electrostatic actuators with multiple degrees of freedom and multiple voltage sources. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2006, 15, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gorthi, S.; Mohanty, A.; Chatterjee, A. Cantilever beam electrostatic MEMS actuators beyond pull-in. J. Micromech. Microeng 2006, 16, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C. Closed form solutions for the pull-in voltage of micro curled beams subjected to electrostatic loads. J. Micromech. Microeng 2006, 16, 648–655. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Lin, D.T.W.; Lee, G.D. In A closed form solution for the pull-in voltage of the micro bridge with initial stress subjected to electrostatic loads. Proceedings of 1st IEEE International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems, Zhuhai, China, 18–21 January 2006; pp. 757–761.

- Stefano, L.; Giuseppe, R. Control of pull-in dynamics in a nonlinear thermoelastic electrically actuated microbeam. J. Micromech. Microeng 2006, 16, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.P. Numerical and analytical study on the pull-in instability of micro-structure under electrostatic loading. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2006, 127, 366–380. [Google Scholar]

- Gusso, A.; Delben, G.J. Influence of the Casimir force on the pull-in parameters of silicon based electrostatic torsional actuators. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2007, 135, 792–800. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Chang, P.Z.; Chuang, W.C. An approximate analytical solution to the pull-in voltage of a micro bridge with an elastic boundary. J. Micromech. Microeng 2007, 17, 1870–1876. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Lee, G.D. A closed form solution for the pull-in voltage of the micro bridge. Tamkang. J. Sci. Eng 2007, 10, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nayfeh, A.H. Dynamic pull-in phenomenon in MEMS resonators. Nonlinear Dyn 2007, 48, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaleem, F.A.; Younis, M.I.; Ouakad, H.M. On the nonlinear resonances and dynamic pull-in of electrostatically actuated resonators. J. Micromech. Microeng 2009, 19, 045013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G.; Li, H.G. Electrostatic micromotor and its reliability. Microelectron. Reliab 2005, 45, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Quevy, E.; Bigotte, P.; Collard, D.; Buchaillot, L. Large stroke actuation of continuous membrane for adaptive optics by 3D self-assembled microplates. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2002, 95, 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.K.; Dutton, R.W. Electrostatic micromechanical actuator with extended range of travel. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2000, 9, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, E.S.; Senturia, S.D. Extending the travel range of analog-tuned electrostatic actuators. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1999, 8, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Legtenberg, R.; Gilbert, J.; Senturia, S.D.; Elwenspoek, M. Electrostatic curved electrode actuators. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1997, 6, 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.J.; Mukherjee, S. Optimal shape design of three-dimensional MEMS with applications to electrostatic comb drives. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng 1999, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.J.; Mukherjee, S.; MacDonald, N.C. Optimal shape design of an electrostatic comb drive in microelectromechanical systems. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1998, 7, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, J.H.; Chen, C.J. The nonlinear electrostatic behavior for shaped electrode actuators. Int. J. Mech. Sci 2005, 47, 1172–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads, J.; Shaw, S.W.; Turner, K.L. Nonlinear Dynamics and Its Applications in Micro- and Nano-Resonators. Proceedings of DSCC 2008: The 2008 ASME Dynamic Systems and Control Conference, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 20–22 October 2008.

- Busta, H.; Amantea, R.; Furst, D.; Chen, J.M.; Turowski, M.; Mueller, C. A MEMS shield structure for controlling pull-in forces and obtaining increased pull-in voltages. J. Micromech. Microeng 2001, 11, 720–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, M.H.; Yang, H.; Yin, H.; Shen, S.Q. Effects of electrostatic forces generated by the driving signal on capacitive sensing devices. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2000, 84, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B.; Adams, G.G.; McGruer, N.E.; Potter, D. A dynamic model, including contact bounce, of an electrostatically actuated microswitch. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2002, 11, 276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.M.; Wang, W.J. Structural dynamics of microsystems—Current state of research and future directions. Mech. Syst. Sig. Process 2006, 20, 1015–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi, S.N. Modeling, nonlinear dynamics, and identification of a piezoelectrically actuated microcantilever sensor. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron 2008, 13, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of electrostatically actuated resonant MEMS sensors under parametric excitation. IEEE Sens. J 2007, 7, 370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, S.B.; Pelesko, J.A. Dynamics of a canonical electrostatic MEMS/NEMS system. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ 2008, 20, 609–641. [Google Scholar]

- Leus, V.; Elata, D. On the dynamic responses of electrostatic MEMS switches. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2008, 17, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.J.; Uttamchandani, D. Dynamic response modelling and characterization of a vertical electrothermal actuator. J. Micromech. Microeng 2009, 19, 075014. [Google Scholar]

- Fargas, M.A.; Costa, C.R.; Shkel, A.M. Modeling the electrostatic actuation of MEMS: State of the art 2005; IOC-DT-P-2005-18; Institute of Industrial and Control Engineering: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R.C.; Porfiri, M.; Spinello, D. Review of modeling electrostatically actuated microelectromechanical systems. Smart Mater. Struct 2007, 16, R23–R31. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, M.; Yang, H. Squeeze film air damping in MEMS. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2007, 136, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Veijola, T. Equivalent-circuit model of the squeezed gas film in a silicon accelerometer. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1995, 48, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, X. Study on the squeezed air-damping on MEMS parallel plates. China Mech. Eng 2005, 16, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y. The Analysis of Squeezed Air-Damping on the Planar MEMS Structures; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 811–812. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D. Air damping in micro-beam resonators. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2007, 29, 841–844. [Google Scholar]

- Blech, J.J. On isothermal squeeze films. J. Lubr. Technol. (Trans. ASME) 1983, 105, 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Tung, R.; Raman, A.; Sumali, H.; Sullivan, J.P. Squeeze-film damping of flexible microcantilevers at low ambient pressures: Theory and experiment. J. Micromech. Microeng 2009, 19, 105029. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, L.; Rocha, L.A.; Cretu, E.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. Squeezed film damping measurements on a parallel-plate MEMS in the free molecule regime. J. Micromech. Microeng 2009, 19, 074021. [Google Scholar]

- Suijlen, M.A.J.; Koning, J.J.; van Gils, M.A.J.; Beijerinck, H.C.W. Squeeze film damping in the free molecular flow regime with full thermal accommodation. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2009, 156, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, A.C.J.; Wang, F.-Y. Nonlinear dynamics of a micro-electro-mechanical system with time-varying capacitors. J. Vib. Acoust 2004, 126, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Davidson, A.; Lin, Q. Simulation studies on nonlinear dynamics and chaos in a MEMS cantilever control system. J. Micromech. Microeng 2004, 14, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Aluru, N.R. Linear, nonlinear and mixed-regime analysis of electrostatic MEMS. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2001, 91, 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G. Nonlinear dynamical system of micro-cantilever under combined parametric and forcing excitations in MEMS. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2005, 119, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.G.; Bertsch, F.M.; Shaw, K.A.; MacDonald, N.C. Independent tuning of linear and nonlinear stiffness coefficients [actuators]. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1998, 7, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.H.; Baskaran, R.; Tumer, K.L. Effect of cubic nonlinearity on auto-parametrically amplified resonant MEMS mass sensor. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2002, 102, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Moon, W.; Choi, J.; Park, I.; Bae, D. A multibody-based dynamic simulation method for electrostatic actuators. Nonlinear Dyn 2008, 54, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aluru, N.R.; White, J. Efficient numerical technique for electromechanical simulation of complicated microelectromechanical structures. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1997, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, M.I.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Nayfeh, A. A reduced-order model for electrically actuated microbeam-based MEMS. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2003, 12, 672–680. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.C.; McCarthy, B.; Diao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Harsh, K.F. Computer-aided design for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol 2003, 18, 356–380. [Google Scholar]

- Senturia, S.D.; Harris, R.M.; Johnson, B.P.; Kim, S.; Nabors, K.; Shulman, M.A.; White, J.K. A computer-aided design system for microelectromechanical systems (MEMCAD). J. Microelectromech. Syst 1992, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- De, S.K.; Aluru, N.R. Full-Lagrangian schemes for dynamic analysis of electrostatic MEMS. J. Microelectromech. Syst 2004, 13, 737–758. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.Y.; Wang, L. Influence of bonding parameters on electrostatic force in anodic wafer bonding. Thin Solid Films 2004, 462–463, 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Chang, C.M.; Huang, S.C. Some design considerations on the electrostatically actuated microstructures. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2004, 112, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Miller, W.C. Proceedings of 2003 International Conference on MEMS, NANO and Smart Systems, Banff, Alberta, Canada, 20–23 July 2003; pp. 297–302.

- Younis, M.I. A study of the nonlinear response of a resonant microbeam to an electric actuation. Nonlinear Dyn 2003, 31, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Spearing, S.M. Materials issues in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). Acta. Mater 2000, 48, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G. Contact dynamics between the rotor and bearing hub in an electrostatic micromotor. Microsyst. Technol 2005, 11, 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Srikar, V.T.; Spearing, S.M. Materials selection for microfabricated electrostatic actuators. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2003, 102, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G. Stability, bifurcation and chaos of a high-speed rub-impact rotor system in MEMS. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2006, 127, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisi, A.; Fachin, F.; Mariani, S.; Zerbini, S. Multi-scale analysis of polysilicon MEMS sensors subject to accidental drops: Effect of packaging. Microelectron. Reliab 2009, 49, 340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisi, A.; Kalicinski, S.; Mariani, S.; De Wolf, I.; Corigliano, A. Polysilicon MEMS accelerometers exposed to shocks: Numerical-experimental investigation. J. Micromech. Microeng 2009, 19, 035023. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, S.; Ghisi, A.; Corigliano, A.; Zerbini, S. Multi-scale analysis of MEMS sensors subject to drop impacts. Sensers 2007, 7, 1817–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, S.; Ghisi, A.; Corigliano, A.; Zerbini, S. Modeling impact-induced failure of polysilicon MEMS: A multi-scale approach. Sensors 2009, 9, 556–567. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, S.; Ghisi, A.; Fachin, F.; Cacchione, F.; Corigliano, A.; Zerbini, S. A three-scale FE approach to reliability analysis of MEMS sensors subject to impacts. Meccanica 2008, 43, 469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, S.; Perego, U. Extended finite element method for quasi-brittle fracture. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng 2003, 58, 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Senturia, S.D. Microsystem Design; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg, P.; Yie, H.; Cai, X.; White, J.; Senturia, S. Self-consistent simulation and modeling of electrostatically deformed diaphragms. Proceedings of MEMS’94, Oiso, Japan, January 1994; pp. 28–32.

- Lishchynska, M.; Cordero, N.; Slattery, O.; O’Mahony, C. Modelling electrostatic behaviour of microcantilevers incorporating residual stress gradient and non-ideal anchors. J. Micromech. Microeng 2005, 15, S10–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Wei, C.S. An analytical model considering the fringing fields for calculating the pull-in voltage of micro curled cantilever beams. J. Micromech. Microeng 2007, 17, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, W.C.; Hu, Y.C.; Lee, C.Y.; Shih, W.P.; Chang, P.Z. Electromechanical behavior of the curled cantilever beam. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2009, 8, 033020–033028. [Google Scholar]

- Nayfeh, A.H. Reduced-order models for MEMS applications. Nonlinear Dyn 2005, 41, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.V.; Zhou, N.; Pister, K.S.J. Modified Nodal Analysis for MEMS with Multi-Energy Domains; Computational Publications: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 723–726. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, F.; Li, W.; Rong, H. Creation of the macromodel of equivalent circuit and IP library for clamped-clamped beam microsensor. Res. Prog. Solid State Electr 2004, 24, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.H. Method of system-level dynamic simulation for a MEMS cantilever based on the mechanical description. Chinese J. Sens. Actuators 2006, 19, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.J.; MacDonald, N.C. A micromachined, single-crystal silicon, tunable resonator. J. Micromech. Microeng 1995, 5, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Veijola, T.; Mattila, T.; Jaakkola, O.; Kiihamaki, J.; Lamminmaki, T.; Oja, A.; Ruokonen, K.; Seppa, H.; Seppala, P.; Tittonen, I. Large-displacement modelling and simulation of micromechanical electrostatically driven resonators using the harmonic balance method. IEEE MTT-S Int. Microwave Symp. Dig 2000, 1, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlachmeyer, U.E. Micromachined capacitive accelerometer. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1991, 27, 555–558. [Google Scholar]

- Bergqvist, J.; Gobet, J. Capacitive microphone with a surface micromachined backplate using electroplating technology. J. Microelectromech. Syst 1994, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Harris, I.; Turner, G. A comparison of squeeze-film theory with measurements on a microstructure. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1993, 36, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, R.B.; Hivick, C.; Xu, J.Y. Compact analytical modeling of squeeze film damping with arbitrary venting conditions using a Green’s function approach. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1998, 70, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, S.A.; Chambr Paul, L. Flow of Rarefied Gases; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.Q.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhu, C.C.; Liu, J.H. The theoretical analysis on damping characteristics of resonant microbeam in vacuum. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1999, 77, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.J.; Kamon, M.; Rabinovich, V.L.; Ghaddar, C.; Deshpande, M.; Greiner, K.; Gilbert, J.R. Modeling Gas Damping and Spring Phenomena in MEMS with Frequency Dependent Macro-Models; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc: Interlaken, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Yu, M.; Xie, M. Nonlinear dynamics of lateral micro-resonator including viscous air damping. Chinese J. Mech. Eng 2007, 20, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.M.; Jia, J.Y.; Fan, K.Q. Study on the air damp of the plate movement in the MEMS devices. J. Univ. Electr. Sci. Technol. China 2007, 36, 965–968. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, E.S.; Yang, Y.J.; Senturia, S.D. Low-order models for fast dynamical simulation of MEMS microstructures. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Solid State Sensors and Actuators, Chicago, IL, USA, 16–19 June 1997; pp. 1101–1104.

- Stewart, J.T. Finite element modeling of resonant microelectromechanical structures for sensing applications. Proceedings of Micromachined Devices and Components, Austin, TX, USA, 23–24 October 1995; pp. 643–646.

- Swart, N.R.; Bart, S.F.; Zaman, M.H.; Mariappan, M.; Gilbert, J.R.; Murphy, D. AutoMM: Automatic generation of dynamic macromodels for MEMS devices. Proceedings IEEE MEMS Workshop, Heidelberg, Germany, 25–29 January 1998; pp. 178–183.

- Mukherjee, T. Emerging simulation approaches for micromachined devices. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst 2000, 19, 1572. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G.; Chen, D. Stability, nonlinearity and reliability of electrostatically actuated MEMS devices. Sensors 2007, 7, 760–796. [Google Scholar]

- van Spengen, W.M.; Puers, R.; De Wolf, I. A physical model to predict stiction in MEMS. J. Micromech. Microeng 2002, 12, 702–713. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Ramadoss, R.; Buck, M.; Bright, V.M.; Gupta, K.C.; Lee, Y.C. Reliability testing of flexible printed circuit-based RF MEMS capacitive switches. Microelectron. Reliab 2004, 44, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wibbeler, J.; Pfeifer, G.; Hietschold, M. Parasitic charging of dielectric surfaces in capacitive microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1998, 71, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Knudson, A.R.; Buchner, S.; McDonald, P.; Stapor, W.J.; Campbell, A.B.; Grabowski, K.S.; Knies, D.L.; Lewis, S.; Zhao, Y. The effects of radiation on MEMS accelerometers. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci 1996, 43, 3122–3126. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, K.J.; Behi, F.; Mahadevan, R.; Mehregany, M. In situ friction and wear measurements in integrated polysilicon mechanisms. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1990, 21, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, D.M.; Miller, W.M.; Peterson, K.A.; Dugger, M.T.; Eaton, W.P.; Irwin, L.W.; Senft, D.C.; Smith, N.F.; Tangyunyong, P.; Miller, S.L. Frequency dependence of the lifetime of a surface micromachined microengine driving a load. Microelectron. Reliab 1999, 39, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, H.; Tayebi, N.; Ballarini, R.; Mullen, R.L.; Heuer, A.H. Fracture toughness of polysilicon MEMS devices. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 2000, 82, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Komvopoulos, K. Surface engineering and microtribology for microelectromechanical systems. Wear 1996, 200, 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, S.F.; Mehregany, M.; Tavrow, L.S.; Lang, J.H.; Senturia, S.D. Electric micromotor dynamics. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1992, 39, 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Y.C.; Muller, R.S. Frictional study of IC-processed micromotors. Sensor Actuator A-Phys 1990, 21, 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.L.; Yang, S.R.; Wang, J.Q.; Liu, W.M.; Zhao, Y.P. Preparation and tribological studies of stearic acid self-assembled monolayers on polymer-coated silicon surface. Chem. Mater 2004, 16, 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Huang, P.Y. Wafer-level microelectromechanical system structural material test by electrical signal before pull-in. Appl. Phys. Lett 2007, 90, 121908. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Shih, W.P.; Lee, G.D. A method for mechanical characterization of capacitive devices at wafer level via detecting the pull-in voltages of two test bridges with different lengths. J. Micromech. Microeng 2007, 17, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Shih, W.P.; Lee, G.D. A method for mechanical characterization of capacitive devices at wafer level via detecting the pull-in voltages of two test bridges with different lengths. J. Micromech. Microeng 2007, 17, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, D.J. Free Vibration Analysis of Beams and Shafts; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).