Seed-Carrying Ant Assemblages in a Fragmented Dry Forest Landscape: Richness, Composition, and Ecological Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

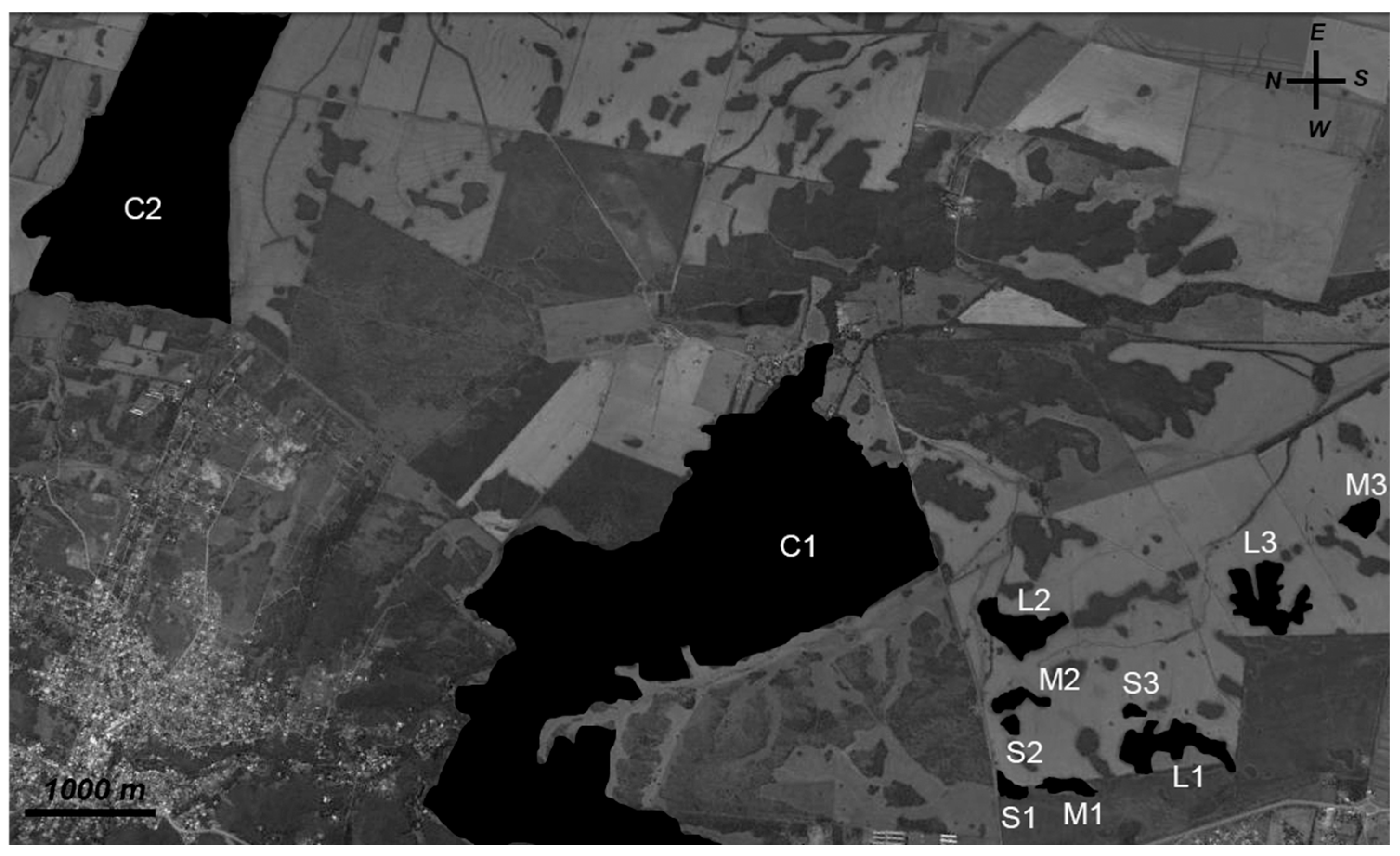

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Sampling Design and Site Selection

2.3. Ant Survey

2.4. Data Analysis

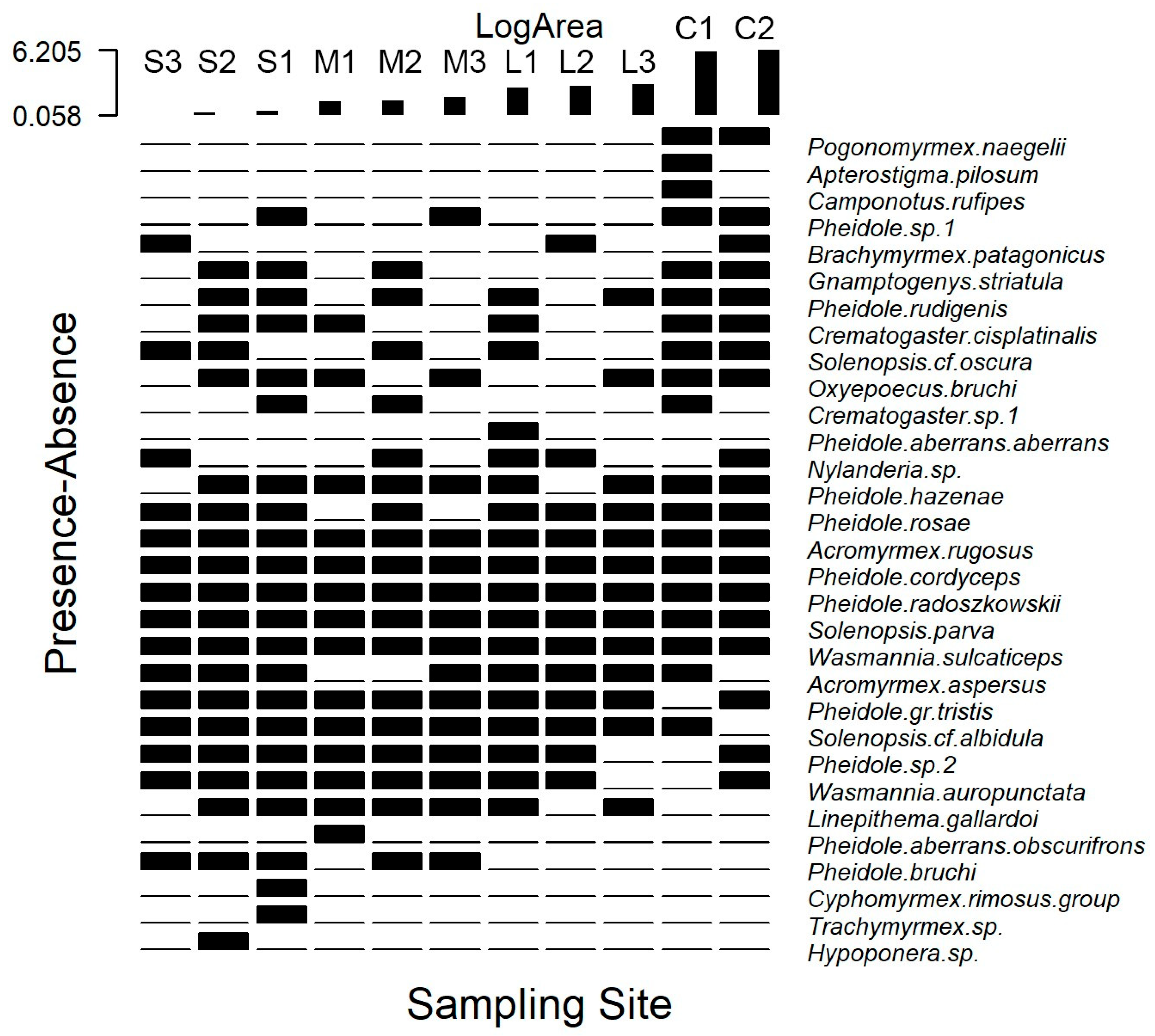

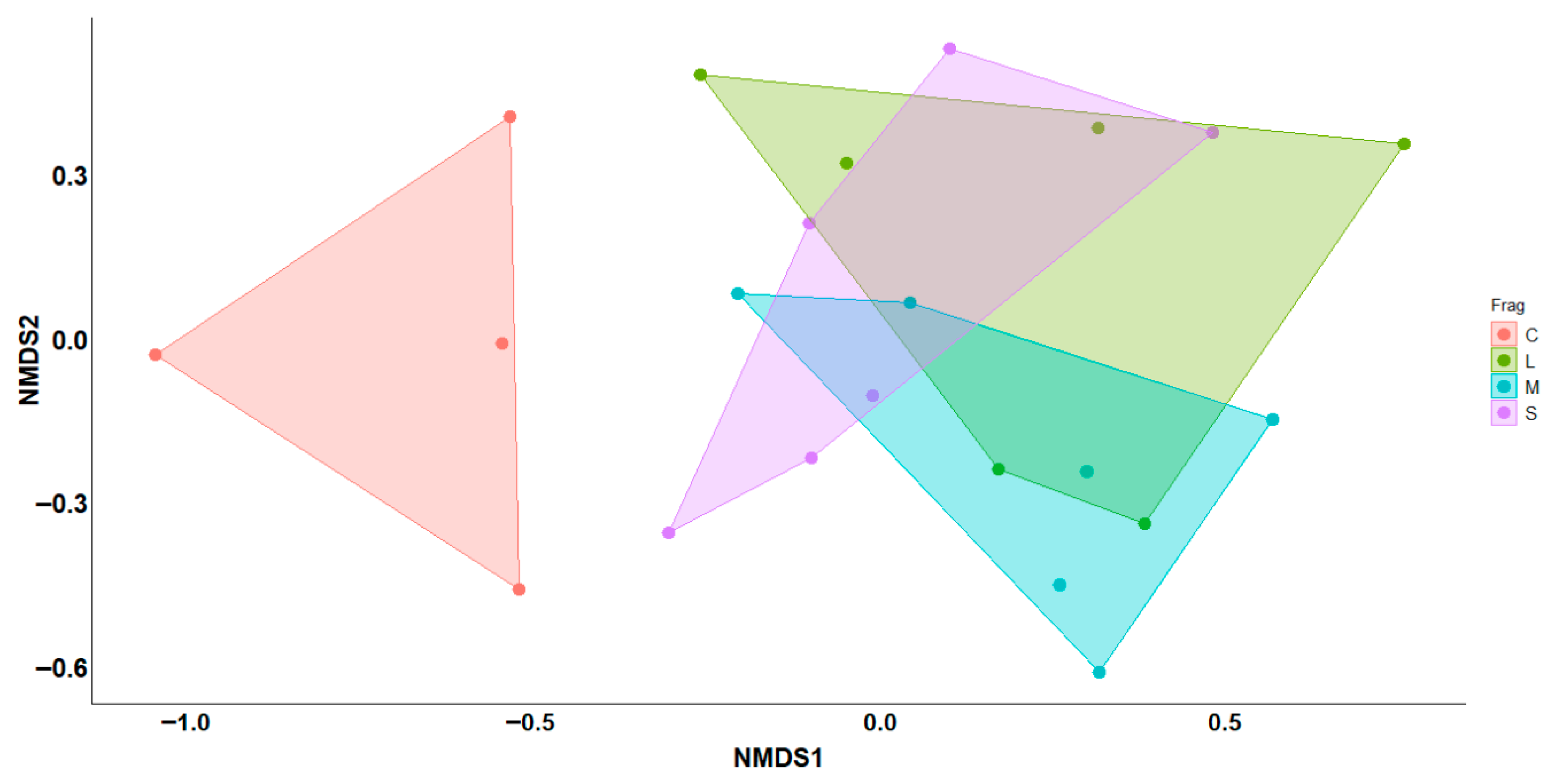

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Arnell, A.P.; Contu, S.; De Palma, A.; Ferrier, S.; Hill, S.L.L.; Hoskins, A.J.; Lysenko, I.; Phillips, H.R.P.; et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.C.; Chen, X.Y.; Corlett, R.T.; Didham, R.K.; Ding, P.; Holt, R.D.; Holyoak, M.; Hu, G.; Hughes, A.C.; Jiang, L.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and biodiversity conservation: Key findings and future challenges. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Banuet, A.; Aizen, M.A.; Alcántara, J.M.; Arroyo, J.; Cocucci, A.; Galetti, M.; García, M.B.; García, D.; Gómez, J.M.; Jordano, P.; et al. Beyond species loss: The extinction of ecological interactions in a changing world. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandor, M.E.; Elphick, C.S.; Tingley, M.W. Extinction of biotic interactions due to habitat loss could accelerate the current biodiversity crisis. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Habitat fragmentation: A long and tangled tale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Koper, N.; Fahrig, L. Overcoming confusion and stigma in habitat fragmentation research. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayle, T.M.; Klimes, P. Improving estimates of global ant biomass and abundance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2214825119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Gray, V.; Oliveira, P.S. The Ecology and Evolution of Ant–Plant Interactions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brühl, C.A.; Eltz, T.; Linsenmair, K.E. Size does matter–effects of tropical rainforest fragmentation on the leaf litter ant community in Sabah, Malaysia. Biod. Conserv. 2003, 12, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Crist, T.O. Biodiversity, species interactions, and functional roles of ants in fragmented landscapes. Myrmecol. News 2009, 12, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abensperg-Traun, M.; Smith, G.T.; Arnold, G.W.; Steven, D.E. The effects of habitat fragmentation and livestock grazing on arthropods in remnants of gimlet woodland. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1281–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Armbrecht, I.; Ulloa-Chacón, P. The little fire ant Wasmannia auropunctata as an indicator of ant diversity in Colombian dry forest. Environ. Entomol. 2003, 32, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debuse, V.J.; King, J.; House, A.P.N. Effect of fragmentation, habitat loss and within-patch characteristics on ant assemblages in semi-arid woodlands. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyra, M.; Pol, R.G.; Galetto, L. Ant community patterns in highly fragmented Chaco forests of central Argentina. Austral Ecol. 2019, 44, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, L.A.; Chifflet, L.; Cuezzo, F.; Sánchez-Restrepo, A.F. Diversity of ground-dwelling ants across three threatened subtropical forests. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2022, 15, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, I.R.; Filgueiras, B.K.C.; Gomes, J.P.; Andersen, A.N. Effects of habitat fragmentation on ant richness and functional composition. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.L.; Vilhena, J.M.S.; Magnusson, W.E.; Albernaz, A.L.K.N. Long-term effects of forest fragmentation on Amazonian ants. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Zelikova, T.J.; Breed, M.D. Effects of habitat disturbance on ant composition and seed dispersal. J. Trop. Ecol. 2008, 24, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, N.G.; Sullivan, L.L. The causes and consequences of seed dispersal. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2023, 54, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.R.; Oliveira, F.M.; Centeno-Alvarado, D.; Wirth, R.; Lopes, A.V.; Leal, I.R. Rapid recovery of ant-mediated seed dispersal along succession in Caatinga. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 554, 121670. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.G.; Bennett, E.M.; Gonzalez, A. Forest fragments modulate ecosystem services. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, J.H. Forest edges and fire ants alter seed shadows. Oecologia 2004, 138, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.; Human, K.G. Effects of harvester ants on plant distribution. Oecologia 1997, 112, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farwig, N.; Berens, D.G. Imagine a world without seed dispersers. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2012, 13, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.V.; Bolger, D.T.; Case, T.J. Effects of fragmentation and invasion on native ants. Ecology 1998, 79, 2041–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cabal, M.A.; Stuble, K.L.; Nuñez, M.A.; Sanders, N.J. Argentine ants disrupt seed dispersal mutualisms. Biol. Lett. 2009, 5, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retana, J.; Xavier Pico, F.; Rodrigo, A. Dual role of harvesting ants as seed predators and dispersers. Oikos 2004, 105, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.S.; Christianini, A.V.; Bieber, A.G.; Pizo, M.A. Anthropogenic disturbance affects ant–fruit interactions. In Ant-Plant Interactions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparri, N.I.; Grau, H.R. Deforestation and fragmentation of Chaco dry forest in NW Argentina. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlenberg, V.; Baumann, M.; Gasparri, N.I.; Piquer-Rodriguez, M.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.; Kuemmerle, T. Soybean production as a driver of Chaco deforestation. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 45, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, D.M. Accumulation by dispossession and socio-environmental conflicts. J. Agrar. Change 2015, 15, 116–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnolo, L.; Cabido, M.; Valladares, G. Plant species richness in Chaco Serrano woodland. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 132, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huais, P.Y.; Grilli, G.; Galetto, L. Impacts of soybean on plant visitation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105055. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, R.; Ashworth, L.; Galetto, L.; Aizen, M.A. Plant reproductive susceptibility to fragmentation. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Urcelay, C.; Galetto, L. Forest fragment size and nutrient availability. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, C.A.; Buffa, L.M.; Valladares, G. Do leaf-cutting ants benefit from forest fragmentation? Insect Conserv. Divers. 2015, 8, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- González, E.; Buffa, L.; Defagó, M.T.; Molina, S.I.; Salvo, A.; Valladares, G. Loss and replacement of ant functional groups in fragmented forests. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 2089–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzabal, M.; Clavijo, J.; Oakley, L.; Biganzoli, F.; Tognetti, P.; Barberis, I.; Maturo, H.M.; Aragón, M.R.; Campanello, P.I.; Prado, D.; et al. Vegetation units of Argentina. Ecol. Austral 2018, 28, 040–063. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgis, M.A.; Cingolani, A.M.; Chiarini, F.; Chiapella, J.; Barboza, G.; Ariza-Espinar, L.; Morero, R.; Gurvich, D.E.; Tecco, P.A.; Subils, R.; et al. Floristic composition of Chaco Serrano forests. Kurtziana 2011, 36, 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cabido, M.; Zeballos, S.R.; Zak, M.; Carranza, M.L.; Giorgis, M.A.; Cantero, J.J.; Acosta, A.T. Native woody vegetation in central Argentina. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2018, 21, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, R.; Galetto, L. Forest fragmentation affects reproductive success. Oecologia 2004, 138, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, S.R.; Davidson, D.W. Comparative structure of harvester ant communities. Ecol. Monogr. 1988, 58, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miretti, M.F.; Pol, R.G.; Paris, C.I.; Elizalde Capellino, V.; Sosa, R.A.; Lopez de Casenave, J. Diversity of seed-carrying ants in the Monte desert. J. Insect Conserv. 2025, 29, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Casenave, J.; Cueto, V.R.; Marone, L. Granivory in the Monte desert, Argentina: Is it less intense than in other arid zones of the world? Global. Ecol. Biogeogr. Lett. 1998, 7, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont Fantozzi, M.M.; Lopez de Casenave, J.; Milesi, F.; Claver, S.; Cueto, V.R. Efecto del tamaño y la forma de la unidad de muestreo sobre la estimación de la riqueza de hormigas acarreadoras de semillas en el desierto del Monte, Argentina. Ecol. Austral 2011, 21, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package, R Package Version 2.5-2. 2013; CRAN—R Project. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrinho, T.G.; Schoereder, J.H.; Sperber, C.F.; Madureira, M.S. Fragmentation alters ant species composition. Sociobiology 2003, 42, 329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, H.L.; Bruna, E.M. Arthropod responses to experimental fragmentation. Zoologia 2012, 29, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvetti, L.E.; Gavier Pizarro, G.; Arcamone, J.R.; Bellis, L.M. Delayed responses and extinction debt in Chaco Serrano birds. Anim. Conserv. 2025, 28, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J.H. Coffee Agroecology: A New Approach to Understanding Agricultural Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services and Sustainable Development; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castellarini, F.; Cuezzo, F.; Toledo, E.L.; Buffa, L.; Orecchia, E.; Visintín, A. Local and landscape drivers of ground-dwelling ant diversity in agroecosystems of Dry Chaco. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 367, 108955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, R.G.; Sagario, M.C.; Marone, L. Grazing impacts on desert plants and seed banks. Acta Oecol. 2014, 55, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Heuss, L.; Grevé, M.E.; Schäfer, D.; Busch, V.; Feldhaar, H. Land-use intensification affects ants. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 4013–4024. [Google Scholar]

- Leponiemi, M.; Schultner, E.; Dickel, F.; Freitak, D. Pesticide exposure affects ant brood and morphology. Ecol. Entomol. 2022, 47, 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, I.M. Species loss in tropical forest fragments. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Achury, R.; Holway, D.A.; Suarez, A.V. Persistent effects of ant invasion and fragmentation. Ecology 2021, 102, e03257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.V.; Richmond, J.Q.; Case, T.J. Prey selection in horned lizards following the invasion of Argentine ants in southern California. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchior, C.; Del-Claro, K.; Oliveira, P.S. Seasonal foraging of Pogonomyrmex naegelii. Arthropod–Plant Interact. 2012, 6, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, A.D.; Majer, J.D.; Dunn, R.R. Keystone ant promotes seed dispersal. Oecologia 2007, 153, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, J.H.; Morin, D.F.; Giladi, I. Uncommon specialization in ant–plant mutualisms. Oikos 2009, 118, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, C.; Espadaler, X. Ant size determines seed dispersal distance. Ecography 1998, 21, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bestelmeyer, B.T.; Wiens, J.A. Effects of land use on ground–foraging ants in the Chaco. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirk, G.I.; Di Pasquo, F.; Lopez de Casenave, J. Diet of two sympatric Pheidole species. Insectes Soc. 2009, 56, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vullo, L.; Lopez de Casenave, J.; Miretti, M.F.; Cao, A.L.; Marone, L.; Pol, R.G. Diet variation in a small harvester ant. Ecol. Entomol. 2024, 49, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complete Model | Df | Pseudo F | R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragments | 3 | 2.97 | 0.33 | 0.001 * |

| Pairwise comparisons | ||||

| Continuous vs. Small | 1 | 6.91 | 0.46 | 0.004 * |

| Continuous vs. Medium | 1 | 4.35 | 0.35 | 0.008 * |

| Continuous vs. Large | 1 | 3.63 | 0.31 | 0.01 * |

| Large vs. Small | 1 | 1.47 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| Large vs. Medium | 1 | 1.06 | 0.09 | 0.34 |

| Medium vs. Small | 1 | 2.18 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pol, R.G.; Pereyra, M.; Galetto, L. Seed-Carrying Ant Assemblages in a Fragmented Dry Forest Landscape: Richness, Composition, and Ecological Implications. Diversity 2025, 17, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120866

Pol RG, Pereyra M, Galetto L. Seed-Carrying Ant Assemblages in a Fragmented Dry Forest Landscape: Richness, Composition, and Ecological Implications. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120866

Chicago/Turabian StylePol, Rodrigo G., Mariana Pereyra, and Leonardo Galetto. 2025. "Seed-Carrying Ant Assemblages in a Fragmented Dry Forest Landscape: Richness, Composition, and Ecological Implications" Diversity 17, no. 12: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120866

APA StylePol, R. G., Pereyra, M., & Galetto, L. (2025). Seed-Carrying Ant Assemblages in a Fragmented Dry Forest Landscape: Richness, Composition, and Ecological Implications. Diversity, 17(12), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120866