Seasonal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Drivers in the Coastal Waters of the Leizhou Peninsula, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

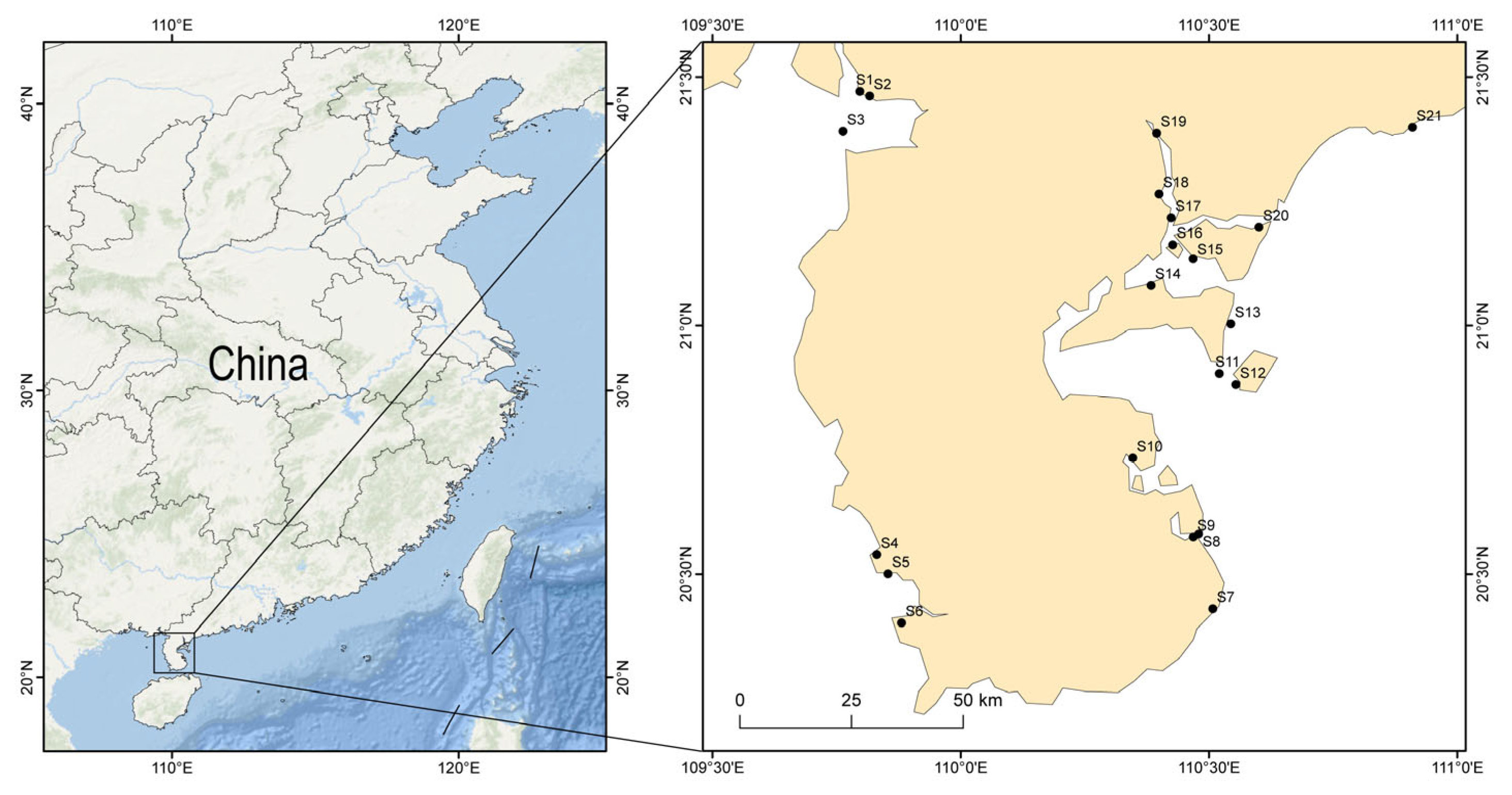

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Process

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Nutrients and Chlorophyll a Analyses

2.3.2. Phytoplankton Analyses

2.4. Statistical Methods

2.5. Water Quality Evaluation Standards

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results

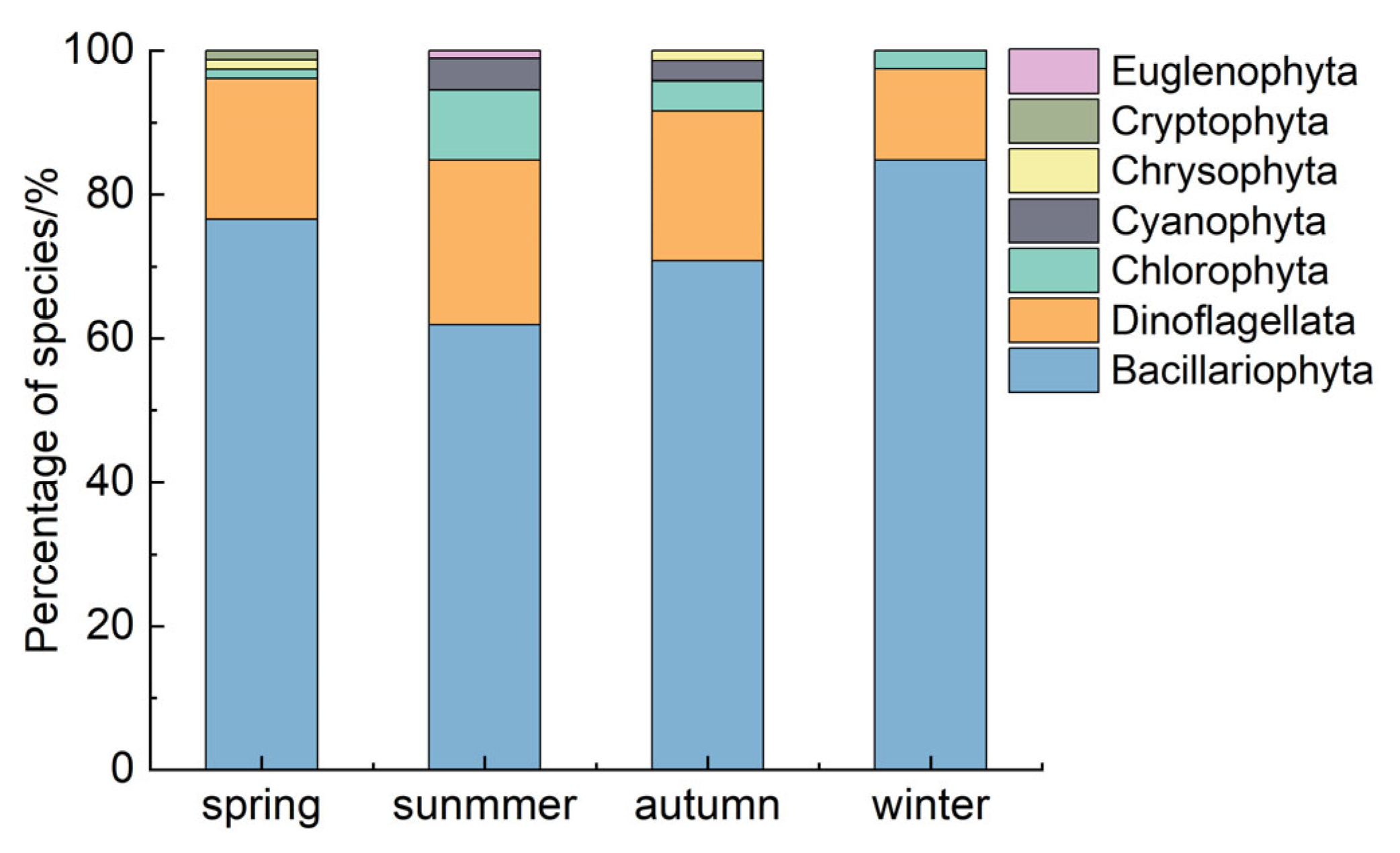

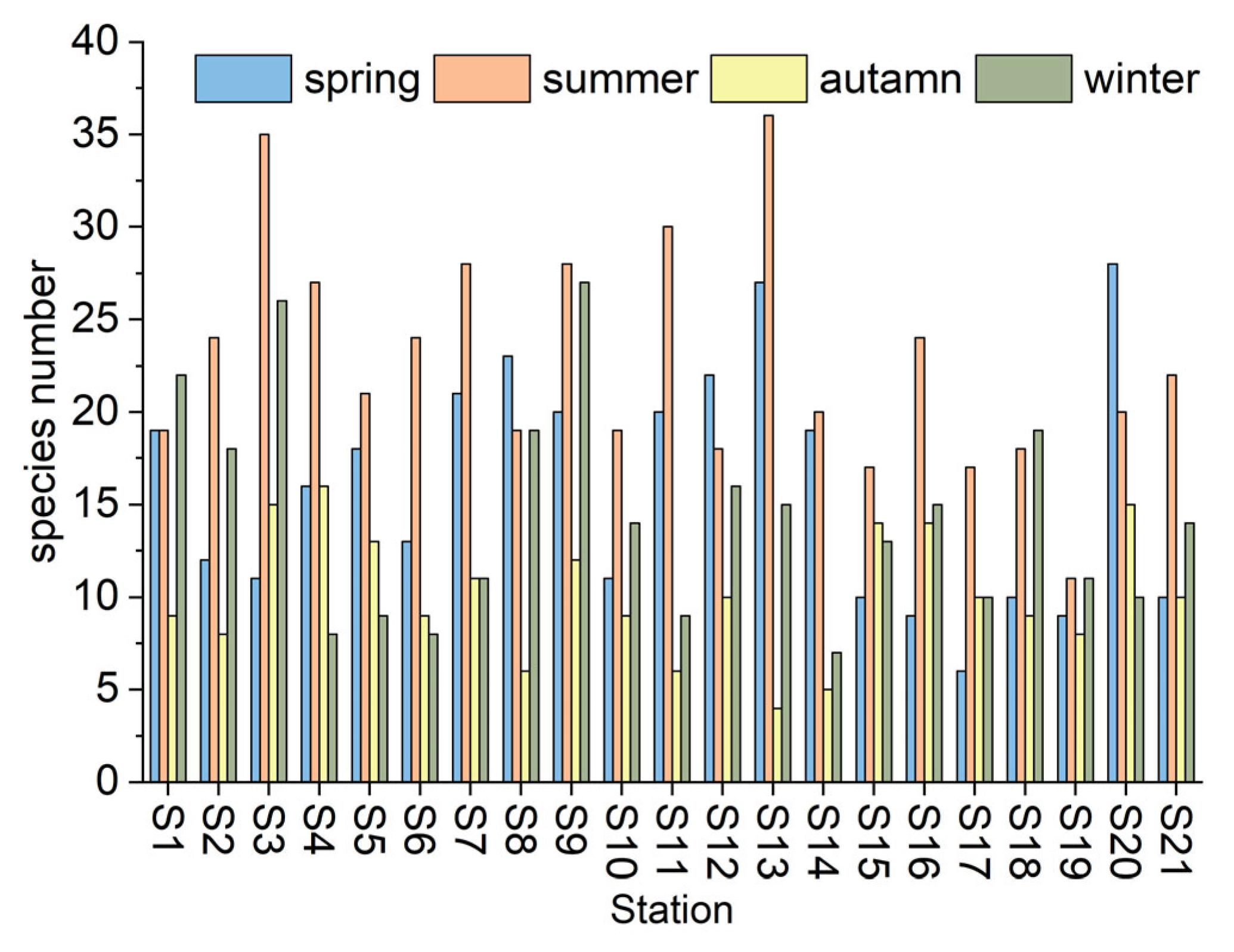

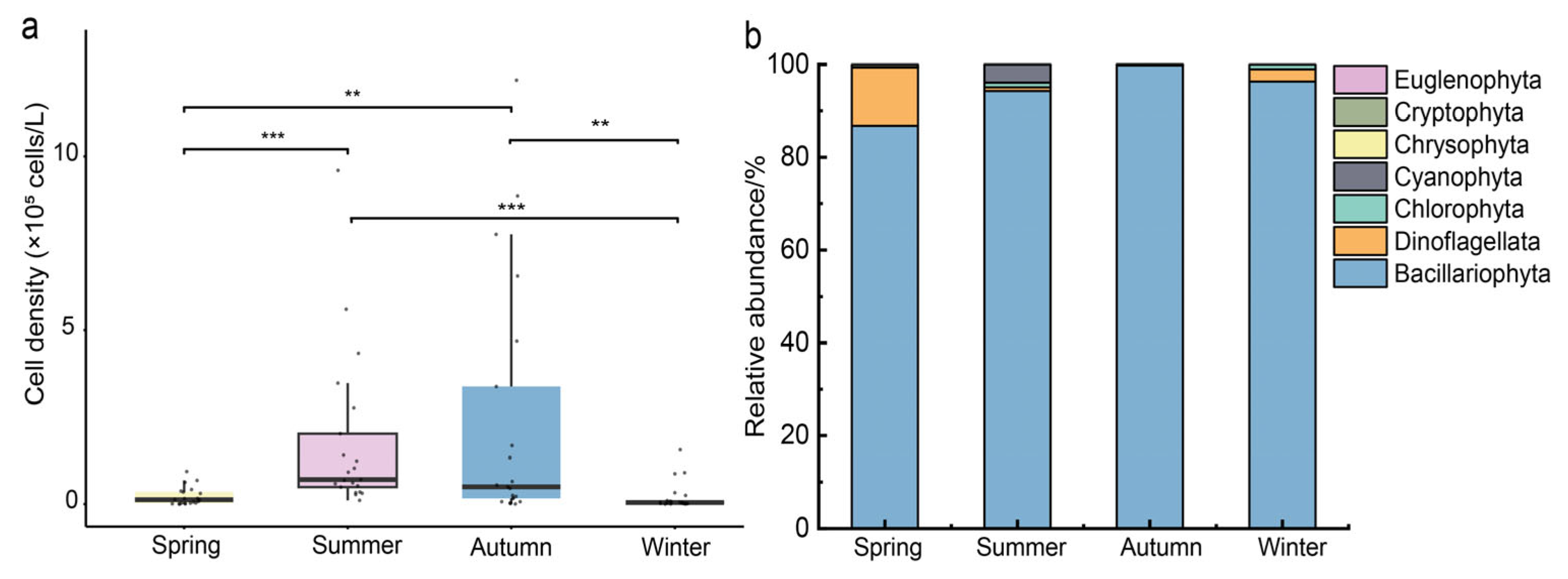

3.1. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Phytoplankton Communities

3.2. Dominant Species

3.3. Spatiotemporal Variation in Phytoplankton Cell Density and Diversity Indices

3.4. Seasonal Variation in Physicochemical Parameters in the Water Body

3.5. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) of Phytoplankton and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Characteristics of Phytoplankton Communities

4.2. Influence of Environmental Factors on Phytoplankton Community Structure Characteristics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walsh, J.J.; Dieterle, D.A.; Lenes, J. A Numerical Analysis of Carbon Dynamics of the Southern Ocean Phytoplankton Community: The Roles of Light and Grazing in Effecting Both Sequestration of Atmospheric CO2 and Food Availability to Larval Krill. Deep Sea Res. Part I 2001, 48, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, G.; Chen, S.; Hu, S. Research on Plankton Community in Three Gorges Reservoir during Its Trial Impoundment. Yangtze River 2012, 43, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.B.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Randerson, J.T.; Falkowski, P. Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components. Science 1998, 281, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, D.M. Use of Algae for Monitoring Rivers III, Edited by J. Prygiel, B.A. Whitton and J. Bukowska (Eds). J. Appl. Phycol. 1999, 11, 596–597. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton, B.A. Changing Approaches to Monitoring during the Period of the ‘Use of Algae for Monitoring Rivers’ Symposia. Hydrobiologia 2012, 695, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. Biodiversity: Population Versus Ecosystem Stability. Ecology 1996, 77, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Knops, J.M.H. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Stability in a Decade-Long Grassland Experiment. Nature 2006, 441, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M.; Hector, A. Partitioning Selection and Complementarity in Biodiversity Experiments. Nature 2001, 412, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Mei, P.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Z. Community Characteristics of Phytoplankton in Yuqiao Reservoir and Relationships with Environmental Factors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 38, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Su, L.; Cai, Y.; Qi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lakshmikandan, M. Effects of Seasonal Variations and Environmental Factors on Phytoplankton Community Structure and Abundance in Beibu Gulf, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 248, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suikkanen, S.; Laamanen, M.; Huttunen, M. Long-Term Changes in Summer Phytoplankton Communities of the Open Northern Baltic Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 71, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongun Sevindik, T.; Çetin, T.; Tekbaba, A.G.; Güzel, U. Impacts of Lake Surface Area on Phytoplankton Community Dynamics and Ecological Status Across 70 Lentic Systems in Türkiye. Ecohydrology 2025, 18, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, F.A.; Ghobrial, M.G.; Hussein, N.R.; Deghady, E.E.D.; Hussein, M.M.A. Long-Term Monitoring of Water Quality and Phytoplankton Community Structure of Lake Manzala, Mediterranean Coast of Egypt. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alprol, A.E.; Ashour, M.; Mansour, A.T.; Alzahrani, O.M.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Gharib, S.M. Assessment of Water Quality and Phytoplankton Structure of Eight Alexandria Beaches, Southeastern Mediterranean Sea, Egypt. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekebayeva, Z.; Bazarkhankyzy, A.; Temirbekova, A.; Rakhymzhan, Z.; Kulzhanova, K.; Beisenova, R.; Kulagin, A.; Askarova, N.; Yevneyeva, D.; Temirkhanov, A.; et al. Ecological Assessment of Phytoplankton Diversity and Water Quality to Ensure the Sustainability of the Ecosystem in Lake Maybalyk, Astana, Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Liao, Y.; Tang, W.; Xie, D.; Wang, T.; Xiong, W.; Bowler, P.A. Fish Biodiversity in Zhanjiang Mangroves National Nature Reserve, China. Turk. J. Zool. 2022, 46, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhao, H.; Gao, H.; Pan, G.; Tian, K. Environmental Capacity and Fluxes of Land-Sourced Pollutants around the Leizhou Peninsula in the Summer. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1280753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xie, Q. Community Characteristics of Phytoplankton in the Coastal Area of Leizhou Peninsula and Their Relationships with Primary Environmental Factors in the Summer of 2010. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2012, 32, 5972–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, S. Biomass Distribution of Phytoplankton and Bacterioplankton in Coastal Areas of Leizhou Peninsula in Summer and Related Affecting Factors. Chin. J. Ecol. 2012, 31, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Qi, Y.; Qian, H.; Liang, S. A Preliminary Study on Phytoplankton and Red-Tide Organisms in Zhanjiang Harbor. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 1994, 25, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Gong, Y.; Sun, S. Study on the Ecological Characteristics of Phytoplankton Community in Zhanjiang Bay. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2012, 2012, 530–538. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, C. Community Structure of Phytoplankton in the Coastal Waters of Leizhou Bay with Its Relationships to Environmental Factors. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2016, 35, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Qi, Y.; Qian, H.; Liang, S. A Study on Phytoplankton and Red Tide Organisms in Leizhou Bay. J. Jinan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1994, 15, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Huang, H.; Huang, L.; Lin, Y.; Li, K.; Lian, J. Phytoplankton of the Coral Reef at Dengloujiao, Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2006, 25, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Xie, W.; Xie, S.; Zhan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Seasonal Variation of Phytoplankton in the Xuwen Coral Reef Region. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2009, 40, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, B. Phytoplankton Community Characteristics in Different Seasons and Their Relationship with Aquaculture in Liusha Bay. Fish. Sci. 2018, 39, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Huang, L.; Tan, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, H. Temporal and Spatial Variation of Phytoplankton Community Structure in Liusha Bay. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2011, 30, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Qi, Y.; Qian, H.; Liang, S. Study on Phytoplankton and Red-Tide Organisms in a South China Sea Bay (Anpu Harbor). J. Jinan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1994, 15, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F. Water and Wastewater Monitoring Methods, 4th ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.M.; Dong, S.G. Illustrated Guide to Common Marine Diatoms in China; China Ocean University Press: Qingdao, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J.Z. Illustrated Guide to Common Freshwater Planktonic Algae in China; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.G.; Lin, M. Atlas of Marine Life in China; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W. Aquatic Biology; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.H.; Chen, C.P.; Sun, L.; Liang, J.R. Common Phytoplankton in Xiamen Waters; Xiamen University Press: Xiamen, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Sun, P.; Sun, X.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Phytoplankton Community Structure and Its Ecological Responses to Environmental Changes in Jinzhou Bay. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 3650–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhm, J.L. Use of Biomass Units in Shannon’s Formula. Ecology 1968, 49, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. Species-Diversity and Pattern-Diversity in the Study of Ecological Succession. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 10, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, R. Information Theory in Ecology. Gen. Syst. 1958, 3, 36–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Phytoplankton community structure and assessment of trophic state in important mariculture area of Dongshan Bay. J. Fish. Res. 2021, 43, 578–586. [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul, F.A.; Hussein, N.R.; Taha, H.M.; Mikhail, S.K.; Shaltout, N.A.; Khairy, H.M. Monitoring of the Ecological Status of the Phytoplankton Dynamics, Water Quality, and Water Types in the Egyptian Mediterranean Coastal Estuary over Two-Decade Intervals. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2024, 28, 1137–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, C. Phytoplankton Community Structure in Relation to Environmental Factors and Ecological Assessment of Water Quality in the Upper Reaches of the Genhe River in the Greater Hinggan Mountains. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 17512–17519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Luan, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X. Net-Phytoplankton Communities and Influencing Factors in the Antarctic Peninsula Region in the Late Austral Summer 2019/2020. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1254043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, C. Diversity and Seasonal Variation of Marine Phytoplankton in Jiaozhou Bay, China Revealed by Morphological Observation and Metabarcoding. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2022, 40, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Sun, P.; Xia, B. A Preliminary Study on Phytoplankton Community Structure and Its Changes in the Jiaozhou Bay. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2005, 23, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhu, B.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Cui, B.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; Peng, M. The Relationship between the Skeletonema costatum Red Tide and Environmental Factors in Hongsha Bay of Sanya, South China Sea. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 253, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Montero, M.; Freer, E. Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Outbreaks in Costa Rica. In Harmful Algae 2002; Steidinger, K.A., Landsberg, J.H., Tomas, C.R., Vargo, G.A., Eds.; Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Institute of Oceanography, and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 482–484. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W.C.; Li, P.; Jian, J.B.; Wang, J.Y.; Lu, S.H. Effects of Solar Ultraviolet Radiation on Photochemical Efficiency of Chaetoceros curvisetus (Bacillariophyceae). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, W.L. Hydrography, Suspended Sediments, Chlorophyll A, Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter and Optical Characteristics of the Pearl River (Zhujiang) Estuary During July and November, 1998. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Deng, L.; Fang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Lin, S.; Liu, H. Detoxification of Domoic Acid from Pseudo-nitzschia by Gut Microbiota in Acartia Erythraea. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, T.; Hu, S.; Xie, X.; Liu, S. Temporal and Spatial Characteristics of Harmful Algal Blooms in Guangdong Coastal Area. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2020, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Yang, Q.; Lin, J. Relationship between Phytoplankton and Environmental Factors in the Waters around Xiamen Island. Mar. Sci. Bull. 1993, 12, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Justić, D.; Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E. Stoichiometric Nutrient Balance and Origin of Coastal Eutrophication. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1995, 30, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortch, Q.; Whitledge, T.E. Does Nitrogen or Silicon Limit Phytoplankton Production in the Mississippi River Plume and Nearby Regions? Cont. Shelf Res. 1992, 12, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Tsuchiya, H. Physiological responses of Si-limited Skeletonema costatum to silicate supply with salinity decrease. Bull. Plankton Soci. 1995, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Gao, J.; Xu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Yang, S. Phytoplankton Community Diversity and Its Environmental Driving Factors in the Northern South China Sea. Water 2022, 14, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchaikani, J.S.; Lipton, A.P. Nutrients and Phytoplankton Dynamics in the Fishing Grounds off Tiruchendur Coastal Waters, Gulf of Mannar, India. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Lin, H.; Luo, X.; Guo, M.; Li, M.; Pang, B.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lan, W. Seasonal Variation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Impact Factors in the Weizhou Island. Guangxi Sci. 2024, 31, 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, F. Analysis Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Characteristics in Daya Bay. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2006, 26, 3948–3958. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, P.W. Environmental Factors Controlling Phytoplankton Processes in the Southern Ocean1. J. Phycol. 2002, 38, 844–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, J.; Frohn, L.M.; Hasager, C.B.; Gustafsson, B.G. Summer Algal Blooms in a Coastal Ecosystem: The Role of Atmospheric Deposition versus Entrainment Fluxes. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2005, 62, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, M.; Cloern, J.E. The Annual Cycles of Phytoplankton Biomass. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3215–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowiak, J.; Hattenrath-Lehmann, T.; Kramer, B.J.; Ladds, M.; Gobler, C.J. Deciphering the Effects of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Temperature on Cyanobacterial Bloom Intensification, Diversity, and Toxicity in Western Lake Erie. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2019, 64, 1347–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E.; Díaz, R.J.; Justić, D. Global Change and Eutrophication of Coastal Waters. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Z. Succession Characteristics and Driving Factors of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in the Germplasm Resources Reserve of Middle Reaches of Huaihe River. Chin. J. Ecol. 2023, 42, 2646–2654. [Google Scholar]

- Thushara, V.; Vinayachandran, P.N.M.; Matthews, A.J.; Webber, B.G.M.; Queste, B.Y. Vertical Distribution of Chlorophyll in Dynamically Distinct Regions of the Southern Bay of Bengal. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 1447–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, U. Interactions between Planktonic Microalgae and Protozoan Grazers. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Spivack, A.J.; Menden-Deuer, S. pH Alters the Swimming Behaviors of the Raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo: Implications for Bloom Formation in an Acidified Ocean. Harmful Algae 2013, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenl, C.Y.; Durbin, E.G. Effects of pH on the Growth and Carbon Uptake of Marine Phytoplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 109, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardall, J.; Raven, J.A. The Potential Effects of Global Climate Change on Microalgal Photosynthesis, Growth and Ecology. Phycologia 2004, 43, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verspagen, J.M.H.; Van De Waal, D.B.; Finke, J.F.; Visser, P.M.; Huisman, J. Contrasting Effects of Rising CO2 on Primary Production and Ecological Stoichiometry at Different Nutrient Levels. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, W. Temperature and Phytoplankton Growth in the Sea. Fish. Bull. 1971, 70, 1063. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, P.W.; Rynearson, T.A.; Armstrong, E.A.; Fu, F.; Hayashi, K.; Hu, Z.; Hutchins, D.A.; Kudela, R.M.; Litchman, E.; Mulholland, M.R.; et al. Marine Phytoplankton Temperature versus Growth Responses from Polar to Tropical Waters—Outcome of a Scientific Community-Wide Study. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinn, D.W. Diatom Community Structure Along Physicochemical Gradients in Saline Lakes. Ecology 1993, 74, 1246–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Mulholland, M.R.; Xu, N.; Duan, S. Effects of Temperature, Irradiance and pCO2 on the Growth and Nitrogen Utilization of Prorocentrum donghaiense. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 77, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuoid, M.R. Influence of Salinity on Seasonal Germination of Resting Stages and Composition of Microplankton on the Swedish West Coast. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 289, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phylum | Dominant Species | Dominance (Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | ||

| Bacillariophyta | Skeletonema costatum | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.21 |

| Chaetoceros lorenzianus | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Thalassiosria pacifica | 0.04 | - | - | 0.24 | |

| Lauderia annulata | - | - | - | 0.03 | |

| Rhizosolenia styliformis | 0.05 | - | - | - | |

| Pseudo-nitzschia sp. | 0.05 | - | - | - | |

| Bacteriastumh hyalium | 0.02 | - | - | - | |

| Chaetoceros densus | 0.03 | - | - | - | |

| Chaetoceros curvisetus | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.02 | - | |

| Asterionella japonica | 0.03 | 0.02 | - | - | |

| Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus | - | 0.09 | - | - | |

| Dinoflagellata | Glenodinium pulvisculus | 0.08 | - | - | - |

| Environmental Factors | Season | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | Significance | |

| T/°C | 24.36 ± 2.97 b | 30.41 ± 0.77 a | 30.27 ± 1.38 a | 20.16 ± 1.32 b | *** |

| PH | 8.29 ± 0.23 a | 7.82 ± 0.25 b | 8.44 ± 0.39 a | 8.31 ± 0.16 a | *** |

| Sal | 30.80 ± 2.33 | 28.76 ± 4.92 | 29.26 ± 3.66 | 30.27 ± 3.07 | ns |

| CODMn/mg L−1 | 1.08 ± 0.34 | 1.33 ± 0.83 | 1.58 ± 0.76 | 1.19 ± 0.31 | ns |

| DIN/mg L−1 | 0.23 ± 0.10 ab | 0.14 ± 0.12 b | 0.31 ± 0.27 a | 0.14 ± 0.07 b | ** |

| DSi/mg L−1 | 0.64 ± 0.50 b | 1.29 ± 0.90 a | 0.27 ± 0.19 c | 1.11 ± 0.50 a | *** |

| DIP/mg L−1 | 0.08 ± 0.05 a | 0.05 ± 0.06 ab | 0.03 ± 0.02 b | 0.08 ± 0.04 a | *** |

| Chl a/μg L−1 | 3.66 ± 3.32 b | 5.20 ± 3.73 ab | 8.79 ± 10.25 a | 2.76 ± 1.89 b | ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Gao, M.; Liu, B.; Fan, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, N.; Hu, Z. Seasonal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Drivers in the Coastal Waters of the Leizhou Peninsula, China. Diversity 2025, 17, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120867

Li J, Gao M, Liu B, Fan Y, Wei J, Zhang Y, Li F, Zhang N, Hu Z. Seasonal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Drivers in the Coastal Waters of the Leizhou Peninsula, China. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jianming, Menghan Gao, Bihong Liu, Yingyi Fan, Junyu Wei, Yulei Zhang, Feng Li, Ning Zhang, and Zhangxi Hu. 2025. "Seasonal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Drivers in the Coastal Waters of the Leizhou Peninsula, China" Diversity 17, no. 12: 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120867

APA StyleLi, J., Gao, M., Liu, B., Fan, Y., Wei, J., Zhang, Y., Li, F., Zhang, N., & Hu, Z. (2025). Seasonal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Environmental Drivers in the Coastal Waters of the Leizhou Peninsula, China. Diversity, 17(12), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120867