The Role of Pavona Coral Growth Strategies in the Maintenance of the Clipperton Atoll Reef

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

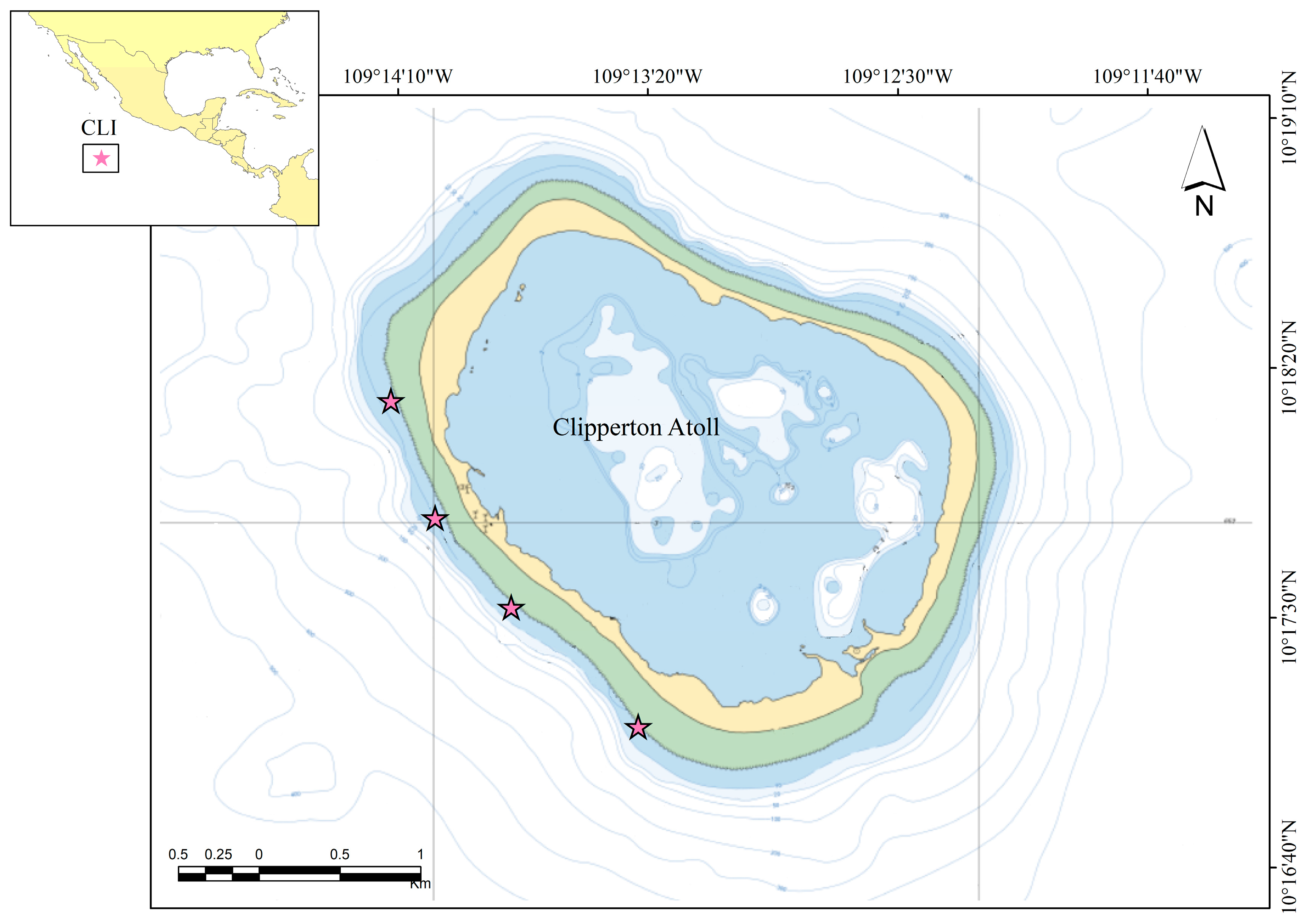

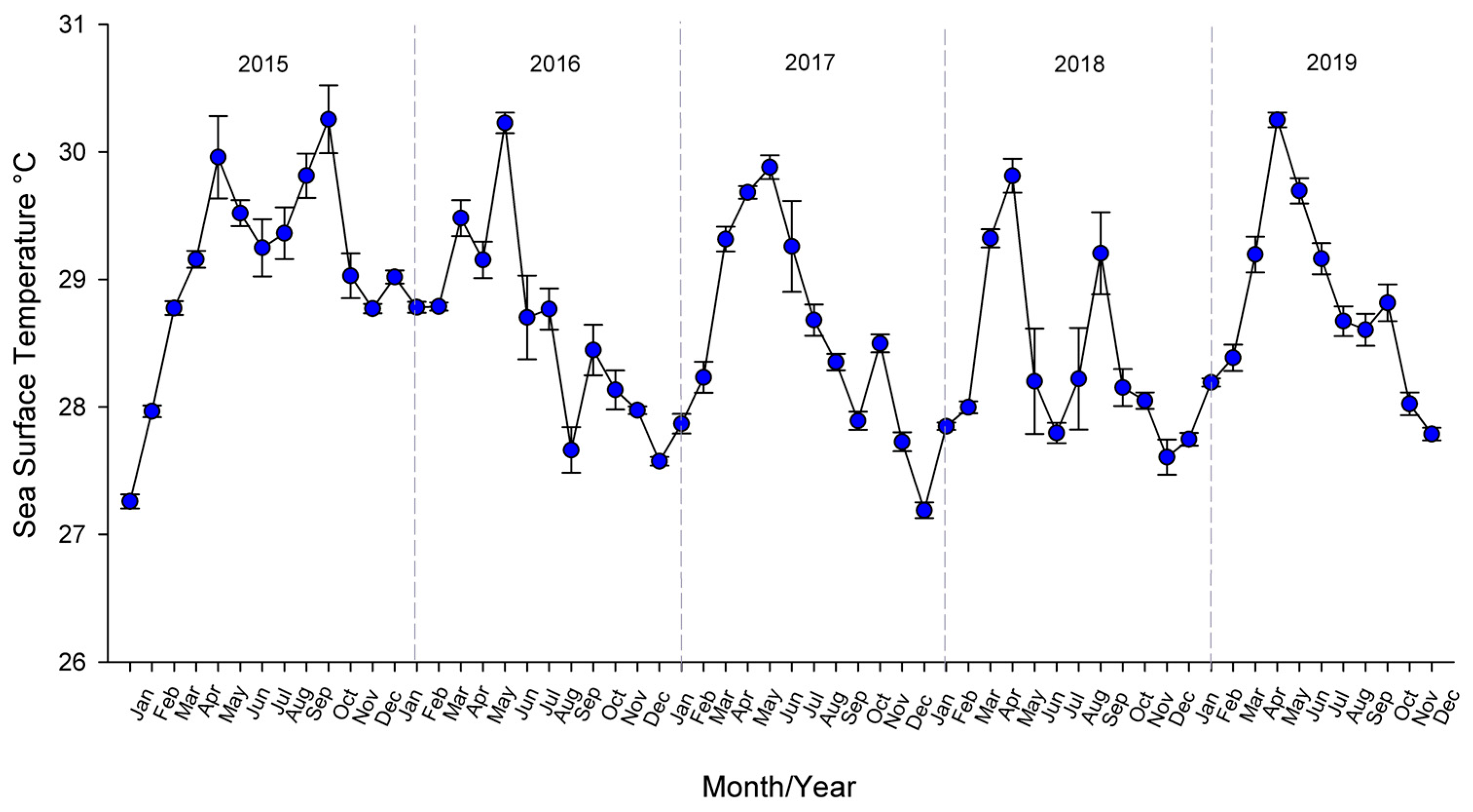

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

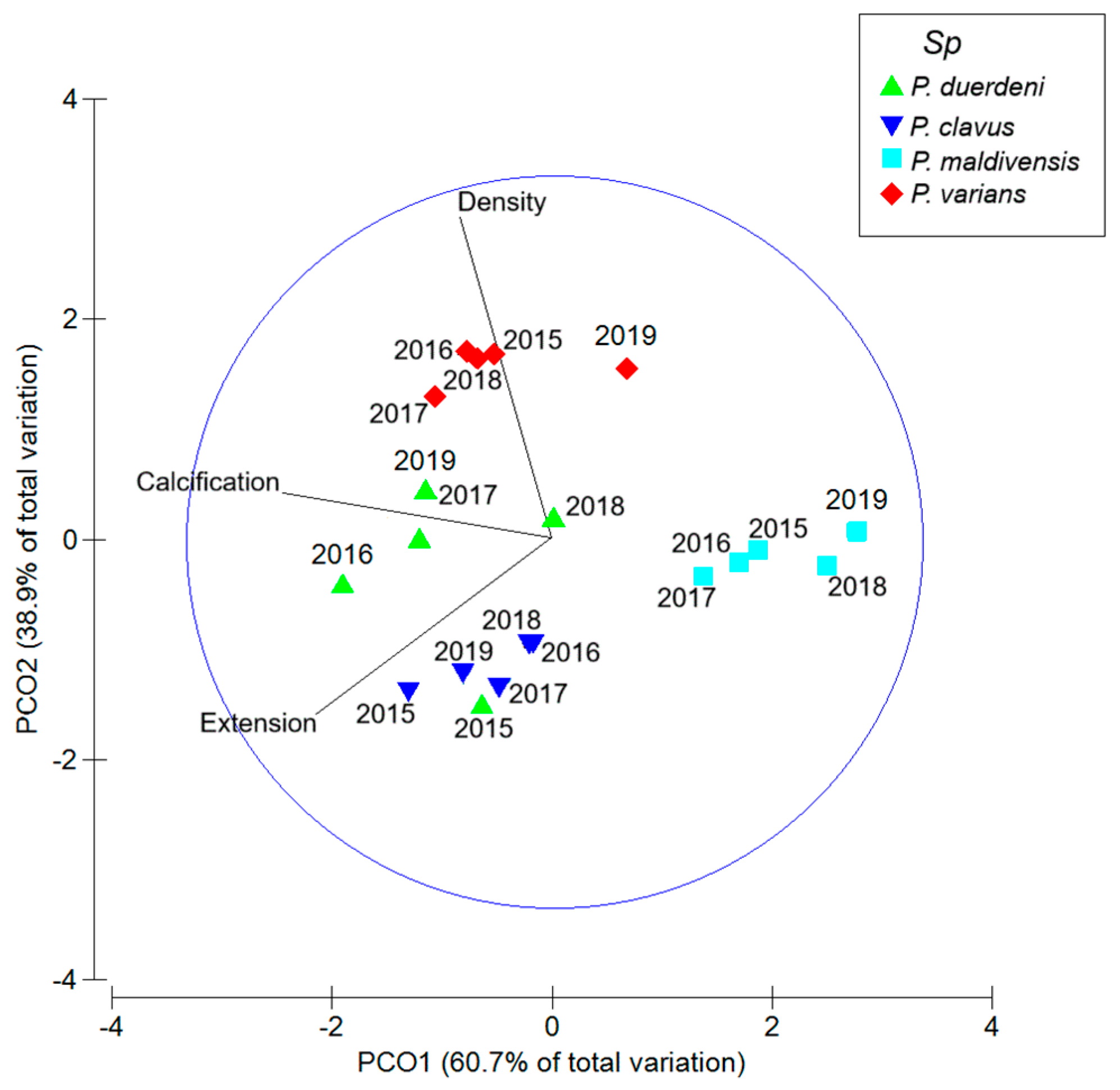

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Norzagaray-López, C.O.; Calderon-Aguilera, L.E.; Hernández-Ayón, J.M.; Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Cabral-Tena, R.A.; Balart, E.F. Low calcification rates and calcium carbonate production in Porites panamensis at its northernmost geographic distribution. Mar. Ecol. 2015, 36, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, A.C.; Kiessling, W.; Bellwood, D.R. Fast-growing species shape the evolution of reef corals. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, J.M. Climate records from corals. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2010, 1, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovski, R.; Nelson, P.A.; Abelson, A. Structural complexity in coral reefs: Examination of a novel evaluation tool on different spatial scales. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D.M.; Tissot, B.N. Evaluating ontogenetic patterns of habitat use by reef fish in relation to the effectiveness of marine protected areas in West Hawaii. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2012, 432, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N.A.; Nash, K.L. The importance of structural complexity in coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs 2013, 32, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddemeier, R.W.; Maragos, J.E.; Knutson, D.W. Radiographic studies of reef coral exoskeletons: Rates and patterns of coral growth. J. Exp. Mar. Bio Ecol. 1974, 14, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.J.; Lough, J.M. Porites growth characteristics in a changed environment: Misima Island, Papua New Guinea. Coral Reefs 1999, 18, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, J.M.; Barnes, D.J.; Devereux, M.J.; Tobin, B.J.; Tobin, S. Variability in Growth Characteristics of Massive Porites on the Great Barrier Reef; CRC Reef Research Centre Technical Report 1999 No 28; CRC Reef Research Centre: Townsville, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Veron, J.E.N. Corals in Space and Time: The Biogeography and Evolution of the Scleractinia; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lough, J.M.; Barnes, D.J. Environmental controls on growth of the massive coral Porites. J. Exp. Mar. Biology Ecol. 2000, 245, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Cabanillas-Teran, N.; Cruz-Ortega, I.; Blanchon, P. Sensitivity of calcification to thermal stress varies among genera of massive reef-building corals. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Barnes, D.J. Densitometry from digitized images of X-radiographs: Methodology for measurement of coral skeletal density. J. Exp. Mar. Biology Ecol. 2007, 344, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté, J.L. Corals and coral reefs of the Pacific coast of Panamá. In Latin American Coral Reefs; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 387–417. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, H.M.; Cortés, J. Coral reef community structure at Caño Island, Pacific Costa Rica. Mar. Ecol. 1989, 10, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, H.M.; Cortes, J. Growth rates of eight species of scleractinian corals in the eastern Pacific (Costa Rica). Bull. Mar. Sci. 1989, 44, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, I.G.; Glynn, P.W.; Cortés, J. Holocene reef history in the eastern Pacific: Mainland Costa Rica, Caño Island, Cocos Island, and Galápagos Islands. In Proceedings of the 7th International Coral Reef Symposium, Guam, Micronesia, 22–27 June 1993; Volume 2, pp. 1174–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Leyte Morales, G.E.L. Coral reefs of Huatulco, West Mexico: Reef development in upwelling Gulf of Tehuantepec. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1997, 45, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Castro, M.Á.; Eyal, G.; Leyte-Morales, G.E.; Hinojosa-Arango, G.; Enríquez, S. Benthic characterization of mesophotic communities based on optical depths in the southern Mexican Pacific coast (Oaxaca). Diversity 2023, 15, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Bonilla, H.; López-Pérez, R.A. Corals and coral-reef communities in the Gulf of California. In Atlas of Coastal Ecosystems in the Western Gulf of California: Tracking Limestone Deposits on the Margin of a Young Sea; Johnson, M.E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2009; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Alvarado, J.J.; Banks, S.; Cortés, J.; Feingold, J.S.; Jiménez, C.; Zapata, F.A. Eastern Pacific coral reef provinces, coral community structure and composition: An overview. In Coral Reefs of the Eastern Tropical Pacific: Persistence and Loss in a Dynamic Environment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 107–176. [Google Scholar]

- Helmus, M.R.; Behm, J.E. Anthropocene: Island Biogeography. In Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; Enochs, I.C.; Sibaja-Cordero, J.; Hernández, L.; Alvarado, J.J.; Breedy, O.; Cruz-Barraza, J.A.; Esquivel-Garrote, O.; Fernández-García, C.; Hermosillo, A.; et al. Marine biodiversity of Eastern Tropical Pacific coral reefs. In Coral Reefs of the Eastern Tropical Pacific: Persistence and Loss in a Dynamic Environment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 203–250. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Veron, J.E.N.; Wellington, G.M. Clipperton Atoll (eastern Pacific): Oceanography, geomorphology, reef-building coral ecology and biogeography. Coral Reefs 1996, 15, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortolero Langarica, J.J.A.; Clua, E.; Rodríguez Zaragoza, F.A.; Caselle, J.E.; Rodríguez Troncoso, A.P.; Adjeroud, M.; Friedlander, A.M.; Cupul Magaña, A.L.; Ballesteros, E.; Carricart Ganivet, J.P.; et al. Spatial and temporal patterns in the coral assemblage at Clipperton Atoll: A sentinel reef in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Coral Reefs 2022, 41, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.J.; Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B. El Niño, echinoid bioerosion and recovery potential of an isolated Galápagos coral reef: A modeling perspective. Mar. Biol. 2017, 164, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, J.W.; Barnard, J.L. Stony corals of the eastern Pacific collected by the Velero III and Velero IV. Allan Hancock Pac Exped. 1952, 16, 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Medellín-Maldonado, F.; Cabral-Tena, R.A.; López-Pérez, A.; Calderón-Aguilera, L.E.; Norzagaray-López, C.O.; Chapa-Balcorta, C.; Zepeta-Vilchis, R.C.; Harris, C. Calcification of the main reef-building coral species on the Pacific coast of southern Mexico. Cienc. Mar. 2016, 42, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Serena, A.; Tortolero-Langarica, J.A.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Clua, E.; Rodríguez-Troncoso, A.P. Growth Patterns of Reef-Building Porites Species in the Remote Clipperton Atoll Reef. Diversity 2025, 17, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Tena, R.A.; Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Lluch-Cota, S.; Paz-García, D.A.; Calderón-Aguilera, L.E.; Norzagaray-López, O.; Balart, E.F. Different calcification rates in males and females of the coral Porites panamensis in the Gulf of California. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 476, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tortolero-Langarica, J.J.A.; Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Cupul-Magaña, A.L.; Rodríguez-Troncoso, A.P. Historical insights on growth rates of the reef-building corals Pavona gigantea and Porites panamensis from the Northeastern tropical Pacific. Mar Environ. Res. 2017, 132, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, E.S.; Alvarez-Filip, L.; Oliver, T.A.; McClanahan, T.R.; Côté, I.M. Evaluating life-history strategies of reef corals from species traits. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.D.; Cohen, A.L.; Rotjan, R.D.; Mangubhai, S.; Sandin, S.A.; Smith, J.E.; Thorrold, S.R.; Dissly, L.; Mollica, N.R.; Obura, D. Increasing coral reef resilience through successive marine heatwaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, G.M.; Glynn, P.W. Environmental influences on skeletal banding in eastern Pacific (Panama) corals. Coral Reefs 1983, 1, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grottoli, A.; Wellington, G. Effect of light and zooplankton on skeletal δ13C values in the eastern Pacific corals Pavona clavus and Pavona gigantea. Coral Reefs 1999, 18, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Reyes-Bonilla, H. New and previous records of scleractinian corals from Clipperton Atoll, eastern Pacific. Pac. Sci. 1999, 53, 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, K.; Abram, N.; Armand, L.; Chase, Z.; De Deckker, P.; Ellwood, M.; Zinke, J. Dealing with climate change: Palaeoclimate research in Australia. Quat. Australas. 2015, 32, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Fiedler, P.C. ENSO variability and the eastern tropical Pacific: A review. Prog Ocean. 2006, 69, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Moreau, M.; Linsley, B.K.; Schrag, D.P.; Corrège, T. Investigation of sea surface temperature changes from replicated coral Sr/Ca variations in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Clipperton Atoll) since 1874. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2014, 412, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Raga, G.B. On the distinct interannual variability of tropical cyclone activity over the eastern North Pacific. Atmósfera 2015, 28, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, T.W. Recent Madreporaria of the Hawaiian Islands and Laysan; US National Museum Bulletin; US National Museum: Washington, DC, USA, 1907; Volume 59, pp. 1–427. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, J.D. Zoophytes. In United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838–1842; Lea and Blanchard: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1846; Volume 7, pp. 1–740. [Google Scholar]

- Verrill, A.E. List of the Polyps and Corals Sent by the Museum of Comparative Zoology to Other Institutions in Exchange, with Annotations; Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology; Museum of Comparative Zoology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1864; Volume 1, pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, J.S. Madreporaria III. Fungida IV. Turbinolidae. In Fauna and Geography of the Maldives and Laccadives Archipelagos; Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1905; Volume 2, pp. 933–957. [Google Scholar]

- Duprey, N.; Bouscher, H.; Jiménez, C. Digital correction of computed X radiographs for coral densitometry. J. Exp. Mar. Biology Ecol. 2012, 438, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, J.M.; Cooper, T.F. New insights from coral growth band studies in an era of rapid environmental change. Earth Sci. Rev. 2011, 108, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.W.; Colley, S.B.; Ting, J.H.; Maté, J.L.; Guzman, H.M. Reef coral reproduction in the eastern Pacific: Costa Rica, Panamá and Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). IV. Agaricidae, recruitment and recovery of Pavona varians and Pavona sp.a. Mar. Biol. 2000, 136, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.; García, J.J.; Tuya, F.; Martínez, B. Environmental factors driving the distribution of the tropical coral Pavona varians: Predictions under a climate change scenario. Mar. Ecol. 2020, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, D.W.; Buddemeier, R.W.; Smith, S.V. Coral chronometers: Seasonal growth bands in reef corals. Science 1972, 177, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.P.; Williams, I.D.; Yeager, L.A.; McPherson, J.M.; Clark, J.; Oliver, T.A.; Baum, J.K. Environmental conditions and herbivore biomass determine coral reef benthic community composition: Implications for quantitative baselines. Coral Reefs 2018, 37, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Castro, M.Á.; Schubert, N.; De Oca, G.A.M.; Leyte-Morales, G.E.; Eyal, G.; Hinojosa-Arango, G. Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems in the Eastern Tropical Pacific: The current state of knowledge and the spatial variability of their depth boundaries. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, N.R.; Guo, W.; Cohen, A.L.; Huang, K.F.; Foster, G.L.; Donald, H.K.; Solow, A.R. Ocean acidification affects coral growth by reducing skeletal density. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 1754–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, P.W.; Ault, J.S. A biogeographic analysis and review of the far eastern Pacific coral reef region. Coral Reefs 2000, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millero, F.J. The marine inorganic carbon cycle. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 308–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzello, D.P.; Kleypas, J.A.; Budd, D.A.; Eakin, C.M.; Glynn, P.W.; Langdon, C. Poorly cemented coral reefs of the eastern tropical Pacific: Possible insights into reef development in a high-CO2 world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10450–10455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ramírez, A. Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2008; Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Reef and Rainforest Research Center: Townsville, Australia, 2008; Volume 20, pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; D’Croz, L. Experimental evidence for high temperature stress as the cause of El Niño-coincident coral mortality. Coral Reefs 1990, 8, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, T.F. Development of contemporary eastern Pacific coral reefs. Mar Biol. 1975, 33, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, I.D.; Perry, C.T. Bleaching impacts on carbonate production in the Chagos Archipelago: Influence of functional coral groups on carbonate budget trajectories. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.T.; Edinger, E.N.; Kench, P. Estimating rates of biologically driven coral reef framework production and erosion: A new census-based carbonate budget methodology and applications to the reefs of Bonaire. Coral Reefs 2012, 31, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, E.H.; Allen, R.G.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas. Biosci. 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Coral reef ecosystems and anthropogenic climate change. Reg. Environ. Change 2011, 11, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L.; Warnes, A.; Comeau, S.; Cornwall, C.E.; Cuttler, M.V.; Naugle, M.; Schoepf, V. Coral calcification mechanisms in a warming ocean and the interactive effects of temperature and light. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, H.M.; Cortés, J. Arrecifes coralinos del Pacífico oriental tropical: Revisión y perspectivas. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1993, 41, 535–557. [Google Scholar]

- Manzello, D.P. Coral growth with thermal stress and ocean acidification: Lessons from the eastern tropical Pacific. Coral Reefs 2010, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.A.; Palumbi, S.R. Do fluctuating temperature environments elevate coral thermal tolerance? Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzello, D.P.; Enochs, I.C.; Bruckner, A.; Renaud, P.G.; Kolodziej, G.; Budd, D.A.; Glynn, P.W. Galápagos coral reef persistence after ENSO warming across an acidification gradient. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 9001–9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.S.; Monismith, S.G.; Fringer, O.B.; Koweek, D.A.; Dunbar, R.B. A coupled wave-hydrodynamic model of an atoll with high friction: Mechanisms for flow, connectivity, and ecological implications. Ocean. Modelling 2017, 110, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, N.; Tamir, R.; Eyal, G.; Loya, Y. Coral morphology portrays the spatial distribution and population size-structure along a 5–100 m depth gradient. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, R.B.; MacIntyre, I.G.; Lewis, S.A.; Hilbun, N.L. Emergent zonation and geographic convergence of coral reefs. Ecology 2005, 86, 2586–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madin, J.S.; Connolly, S.R. Ecological consequences of major hydrodynamic disturbances on coral reefs. Nature 2006, 444, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréfouët, S.; Bruyère, O.; Liao, V.; Le Gendre, R. Hydrodynamical impact of the July 2022 ‘Code Red’distant mega-swell on Apataki Atoll, Tuamotu Archipelago. Glob. Planet. Change 2023, 228, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.F.; Valdivia, A. Coral reef degradation is not correlated with local human population density. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Kerry, J.T.; Álvarez-Noriega, M.; Álvarez-Romero, J.G.; Anderson, K.D.; Baird, A.H.; Wilson, S.K. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 2017, 543, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, R.B.; Precht, W.F. White-band disease and the changing face of Caribbean coral reefs. Hydrobiol 2001, 460, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, K.S.; Hoang, D.T.; Dang, H.N. Ecological status of coral reefs in the Spratly Islands, South China Sea (East Sea) and its relation to thermal anomalies. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 238, 106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Carriquiry, J.; Leyte-Morales, G.; Cupul-Magaña, A. Effects of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and the anti-El Niño event (1997–1999) on coral reefs of the western coast of México. Coral Reefs 2002, 21, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-García, R.; Rodríguez-Troncoso, A.P.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; Mayfield, A.; Cupul-Magaña, A.L. Ephemeral effects of El Niño–Southern Oscillation events on an eastern tropical Pacific coral community. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2020, 71, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J.J.; Sánchez-Noguera, C.; Arias-Godínez, G.; Araya, T.; Fernández-García, C.; Guzmán, A.G. Impact of El Niño 2015–2016 on the coral reefs of the Pacific of Costa Rica: The potential role of marine protection. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2020, 68, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, A.; Granja-Fernández, R.; Ramírez-Chávez, E.; Valencia-Méndez, O.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; González-Mendoza, T.; Martínez-Castro, A. Widespread coral bleaching and mass mortality of reef-building corals in southern mexican Pacific reefs due to 2023 El Niño Warming. Oceans 2024, 5, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; An, M.; Tang, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z. The differential physiological responses to heat stress in the scleractinian coral Pocillopora damicornis are affected by its energy reserve. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 204, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.W.; Maté, J.L.; Baker, A.C.; Calderón, M.O. Coral bleaching and mortality in Panama and Ecuador during the 1997–1998 El Niño-Southern Oscillation event: Spatial/temporal patterns and comparisons with the 1982–1983 event. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001, 69, 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Torres, M.; Treml, E.A.; Acosta, A.; Paz-García, D.A. The Eastern Tropical Pacific coral population connectivity and the role of the Eastern Pacific Barrier. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkachenko, K.S.; Soong, K. Dongsha Atoll: A potential thermal refuge for reef-building corals in the South China Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 127, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Croz, L.; Maté, J.L. Experimental responses to elevated water temperature in genotypes of the reef coral Pocillopora damicornis from upwelling and non-upwelling environments in Panama. Coral Reefs 2004, 23, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Bonilla, H. Coral reefs of the Pacific coast of México. In Latin American Coral Reefs; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Rachello-Dolmen, P.G.; Cleary, D.F.R. Relating coral species traits to environmental conditions in the Jakarta Bay/Pulau Seribu reef system, Indonesia. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 73, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woesik, R.; Sakai, K.; Ganase, A.; Loya, Y. Revisiting the winners and the losers a decade after coral bleaching. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 434, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Millán, M.; Vermeij, M.J.; Alcantar, E.A.; Sandin, S.A. Coral reef assessments based solely on cover mask the active dynamics of coral communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 630, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, T.R.; Chung, M.V.; Vecchi, G.; Sun, J.; Hsieh, T.; Smith, A.J.P. Climate change is probably increasing the intensity of tropical cyclones. In Critical Issues in Climate Change Science; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Year (Yr) | Density (g cm−3) | Extension (cm yr−1) | Calcification (g cm−2 yr−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. duerdeni | 2019 | 1.42 ± 0.19 | 0.86 ± 0.15 | 1.23 ± 0.25 |

| 2018 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 0.91 ± 0.26 | 1.25 ± 0.34 | |

| 2017 | 1.35 ± 0.14 | 1.20 ± 0.28 | 1.62 ± 0.34 | |

| 2016 | 1.28 ± 0.24 | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 1.69 ± 0.50 | |

| 2015 | 1.26 ± 0.29 | 1.06 ± 0.53 | 1.25 ± 0.48 | |

| P. clavus | 2019 | 1.28 ± 0.16 | 1.21 ± 0.27 | 1.53 ± 0.28 |

| 2018 | 1.31 ± 0.20 | 1.12 ± 0.38 | 1.42 ± 0.35 | |

| 2017 | 1.28 ± 0.26 | 1.07 ± 0.28 | 1.32 ± 0.27 | |

| 2016 | 1.31 ± 0.27 | 1.08 ± 0.29 | 1.40 ± 0.43 | |

| 2015 | 1.25 ± 0.29 | 1.15 ± 0.40 | 1.35 ± 0.27 | |

| P. varians | 2019 | 1.86 ± 0.25 | 0.70 ± 0.29 | 1.28 ± 0.48 |

| 2018 | 1.81 ± 0.26 | 0.74 ± 0.27 | 1.31 ± 0.34 | |

| 2017 | 1.72 ± 0.17 | 0.64 ± 0.46 | 1.05 ± 0.64 | |

| 2016 | 1.74 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.59 | 1.35 ± 0.90 | |

| 2015 | 1.58 ± 0.22 | 1.00 ± 0.29 | 1.45 ± 0.22 | |

| P. maldivensis | 2019 | 1.21 ± 0.11 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.06 |

| 2018 | 1.19 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.67 ± 0.23 | |

| 2017 | 1.21 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.20 | 0.92 ± 0.27 | |

| 2016 | 1.19 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.23 | |

| 2015 | 1.19 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.26 | 0.82 ± 0.27 |

| Species | No. Colonies | No. Tracks | Growth Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g cm−3) | Extension (cm yr−1) | Calcification (g cm−2 yr−1) | |||

| P. duerdeni | 4 | 8 | 1.3 ± 0.18 | 0.95 ± 0.22 | 1.22 ± 0.26 |

| P. clavus | 5 | 15 | 1.19 ± 0.22 | 0.98 ± 0.33 | 1.16 ± 0.38 |

| P. varians | 5 | 10 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.20 | 1.20 ± 0.28 |

| P. maldivensis | 4 | 8 | 1.22 ± 0.09 | 0.67 ± 0.17 | 0.82 ± 0.212 |

| N | 18 | 41 | |||

| PERMANOVA | PERMDISP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of variation | Pseudo-F | p | CV% | F | p | |

| Temperature | 0.25 | 0.77 | 3.4 | Temperature | 1.10 | 0.38 |

| Species | 9.91 | 0.0001 | 26.0 | Species | 17.15 | 0.0001 |

| Year | 0.32 | 0.95 | 7.7 | Year | 0.41 | 0.81 |

| Specie x Year | 0.29 | 0.99 | 16.28 | Specie x Year | 3.79 | 0.0002 |

| Residuals | 46.5 | |||||

| PAIRWISE COMPARISONS | PERMDISP | |||||

| Groups | t | p | Groups | F | p | |

| P. due vs. P. cla | 1.1 | 0.25 | P. due vs. P. cla | 3.3 | 0.0015 | |

| P. due vs. P. mal | 4.3 | 0.0001 | P. due vs. P. mal | 1.7 | 0.097 | |

| P. due vs. P. var | 2.6 | 0.0027 | P. due vs. P. var | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| P. cla vs. P. mal | 3.5 | 0.0001 | P. cla vs. P. mal | 6.3 | 0.0001 | |

| P. cla vs. P. var | 3.5 | 0.0001 | P. cla vs. P. var | 4.3 | 0.0001 | |

| P. mal vs. P. var | 5.3 | 0.0001 | P. mal vs. P. var | 1.3 | 0.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ochoa-Serena, A.; Tortolero-Langarica, J.d.J.A.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Clua, E.E.G.; Rodríguez-Troncoso, A.P. The Role of Pavona Coral Growth Strategies in the Maintenance of the Clipperton Atoll Reef. Diversity 2025, 17, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120854

Ochoa-Serena A, Tortolero-Langarica JdJA, Rodríguez-Zaragoza FA, Carricart-Ganivet JP, Clua EEG, Rodríguez-Troncoso AP. The Role of Pavona Coral Growth Strategies in the Maintenance of the Clipperton Atoll Reef. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120854

Chicago/Turabian StyleOchoa-Serena, Ania, José de Jesús Adolfo Tortolero-Langarica, Fabián Alejandro Rodríguez-Zaragoza, Juan Pablo Carricart-Ganivet, Eric Emile G. Clua, and Alma Paola Rodríguez-Troncoso. 2025. "The Role of Pavona Coral Growth Strategies in the Maintenance of the Clipperton Atoll Reef" Diversity 17, no. 12: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120854

APA StyleOchoa-Serena, A., Tortolero-Langarica, J. d. J. A., Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F. A., Carricart-Ganivet, J. P., Clua, E. E. G., & Rodríguez-Troncoso, A. P. (2025). The Role of Pavona Coral Growth Strategies in the Maintenance of the Clipperton Atoll Reef. Diversity, 17(12), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120854