Enhancing Endangered Feline Conservation in Asia via a Pose-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Individual Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.1.1. Wild Amur Tiger Dataset

2.1.2. Wild Snow Leopard Dataset

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Pose-Guided and Adaptive Regularization-Based Re-Identification Network

2.2.2. Loss Function

2.2.3. Introduction of Adaptive Regularization

2.2.4. Optimization Methods

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

- Cumulative Matching Characteristics (CMC). Suppose the query set contains N samples, and the gallery set contains M samples. For a given query sample q, there are m ground truth matches (i.e., samples with the same ID) in the gallery. The retrieval results are ranked in descending order of similarity as:. For each query q, the Rank-k indicator is defined as:The Rank-k accuracy is computed by averaging over all queries:We report Rank-1, Rank-5, and Rank-10 accuracies as standard evaluation metrics.

- Mean Average Precision (mAP). We first define a binary indicator function :The precision at rank k is defined as:The Average Precision (AP) for a single query is computed as:Finally, the mean Average Precision (mAP) is obtained by averaging AP over all N queries:

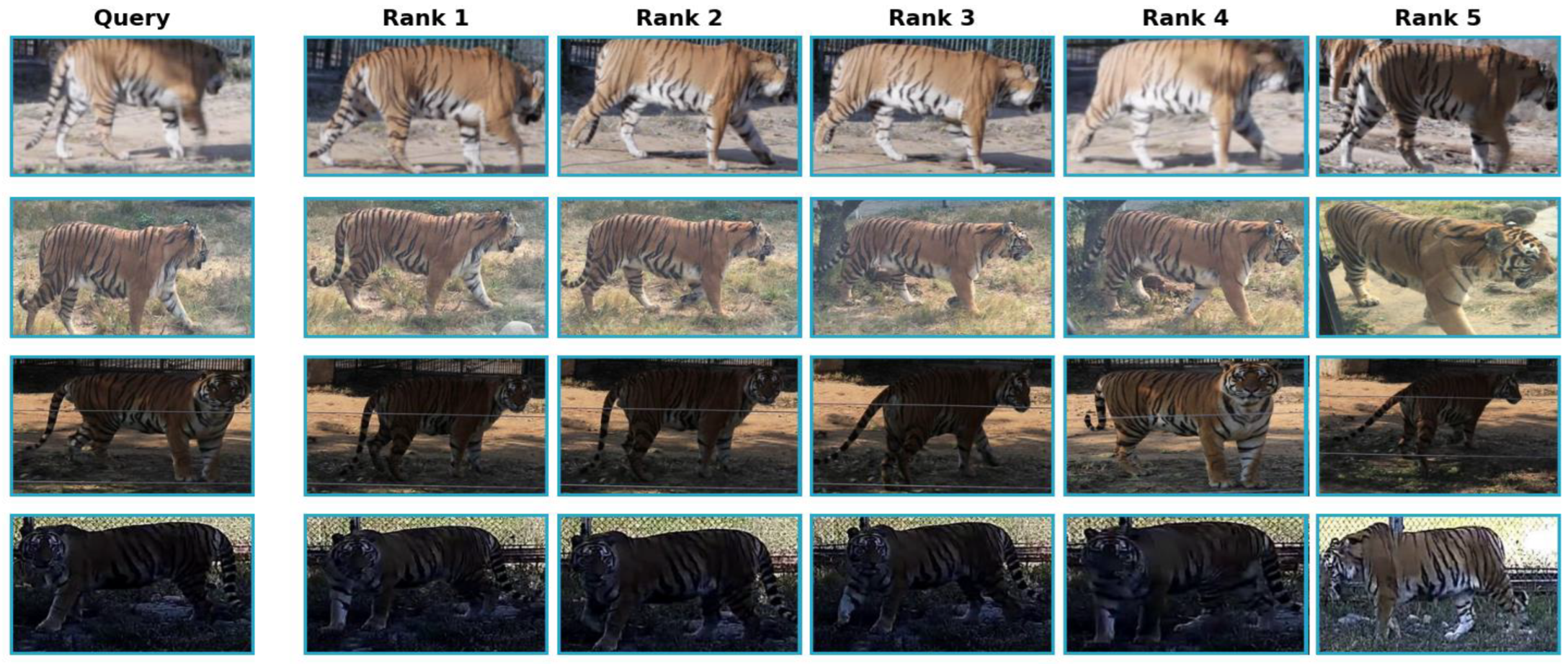

3.2. Comparison with Existing Methods

3.3. Ablation Experiment

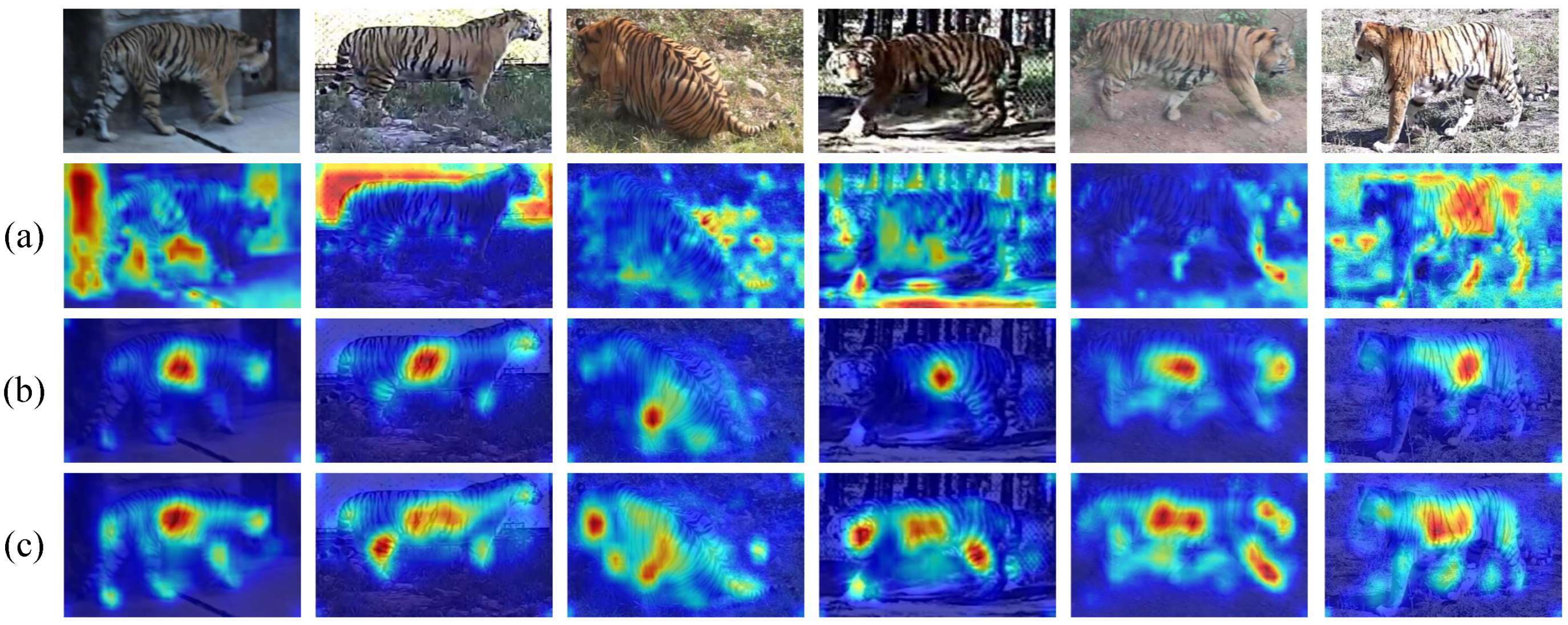

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Traditional CNN Methods

4.2. Comparison with Transformer-Based Methods

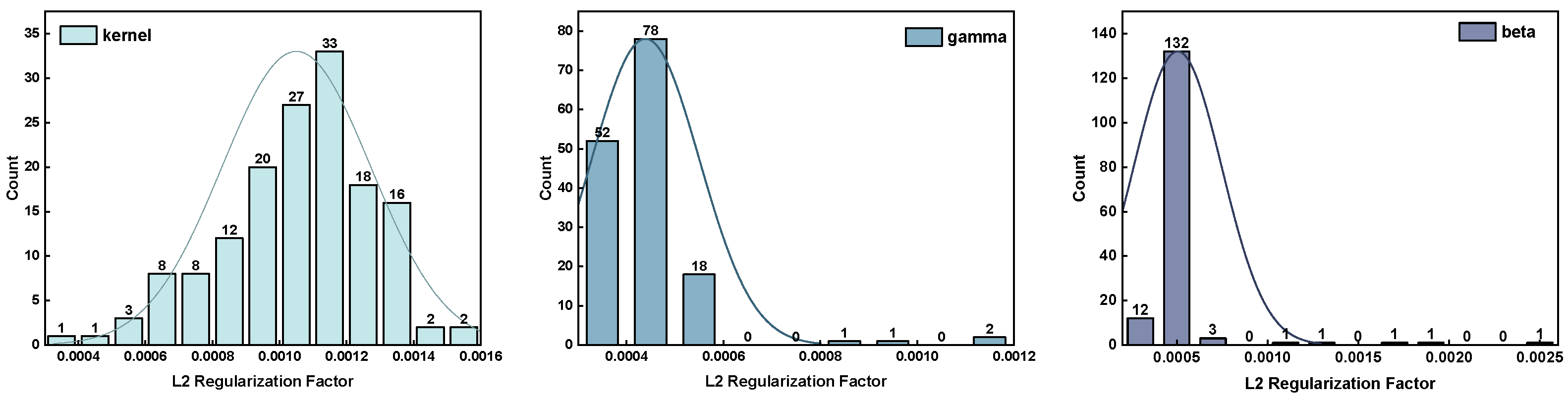

4.3. Effectiveness Analysis of Adaptive Regularization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, S.; Kumaresan, P.R.; Saxena, A.; Mishra, M.R.; Upadhyay, L.; Arul Sabareeswaran, T.A.; Alimudeen, S.; Magrey, A.H. Wildlife Conservation and Management: Challenges and Strategies. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2023, 44, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiby, L.; Lovell, P.; Patil, N.; Kumar, N.S.; Gopalaswamy, A.M.; Karanth, K.U. A Tiger Cannot Change Its Stripes: Using a Three-Dimensional Model to Match Images of Living Tigers and Tiger Skins. Biol. Lett. 2009, 5, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Jeong, D.; Hyun, J.Y.; Marchenkova, T.; Matiukhina, D.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.Y.; Li, Y.; Darman, Y.; Min, M.S.; et al. Genetic Insights and Conservation Strategies for Amur Tigers in Southwest Primorye Russia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Andrew Royle, J.; Smith, J.L.; Zou, L.; Lü, X.; Li, T.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Feng, R.; Bian, Y.; et al. Living on the Edge: Opportunities for Amur Tiger Recovery in China. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 217, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. IUCN Annual Report 2017; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Alexander, J.S.; Durbach, I.; Kodi, A.R.; Mishra, C.; Nichols, J.; MacKenzie, D.; Ale, S.; Lovari, S.; Modaqiq, A.W.; et al. PAWS: Population Assessment of the World’s Snow Leopards. In Snow Leopards; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Vallarasu, K. Environmental Conservation and Sustainability: Strategies for a Greener Future. Int. J. Multidimens. Res. Perspect. 2023, 1, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreychev, A.V. A New Methodology for Studying the Activity of Underground Mammals. Biol. Bull. 2018, 45, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tang, S.; Li, X.; Menghe, D.; Bao, W.; Xiang, C.; Gao, F.; Bao, W. A Study of Population Size and Activity Patterns and Their Relationship to the Prey Species of the Eurasian Lynx Using a Camera Trapping Approach. Animals 2019, 9, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caragiulo, A.; Pickles, R.S.A.; Smith, J.A.; Smith, O.; Goodrich, J.; Amato, G. Tiger (Panthera tigris) Scent DNA: A Valuable Conservation Tool for Individual Identification and Population Monitoring. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2015, 7, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Yang, H.; Feng, L.; Mou, P.; Wang, T.; Ge, J. Estimating the Population Size and Genetic Diversity of Amur Tigers in Northeast China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibhai, S.K.; Gu, J.; Jewell, Z.C.; Morgan, J.; Liu, D.; Jiang, G. ‘I Know the Tiger by His Paw’: A Non-Invasive Footprint Identification Technique for Monitoring Individual Amur Tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) in Snow. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 73, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Jhala, Y.; Sawarkar, V.B. Identification of Individual Tigers (Panthera Tigris) from Their Pugmarks. J. Zool. 2005, 267, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerley, L.L.; Salkina, G.P. Using Scent-Matching Dogs to Identify Individual Amur Tigers from Scats. J. Wildl. Manag. 2007, 71, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liu, D.; Cui, Y.; Xie, J.; Roberts, N.J.; Jiang, G. Amur Tiger Stripes: Individual Identification Based on Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Integr. Zool. 2020, 15, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Xu, J.; Roberts, N.J.; Liu, D.; Jiang, G. Individual Automatic Detection and Identification of Big Cats with the Combination of Different Body Parts. Integr. Zool. 2023, 18, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajdel, W.; Zivkovic, Z.; Krose, B. Keeping Track of Humans: Have I Seen This Person Before? In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 2081–2086. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.; Taylor, G.W.; Linquist, S.; Kremer, S.C. Past, Present and Future Approaches Using Computer Vision for Animal Re-identification from Camera Trap Data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, H. Computer Assisted Individual Identification of Sperm Whale Flukes. In Individual Recognition of Cetaceans: Use of Photo-Identification and Other Techniques to Estimate Population Parameters; Hammond, P.S., Mizroch, S.A., Donovan, G.P., Eds.; Report of the International Whaling Commission: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ravela, S.; Gamble, L. On Recognizing Individual Salamanders. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP ’04), Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–21 May 2004; Volume 5, pp. 742–747. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.J.; Bell, I.P.; Miller, J.J.; Gash, P.P. Automated Marine Turtle Photograph Identification Using Artificial Neural Networks, with Application to Green Turtles. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 452, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Tang, H.; Qian, R.; Lin, W. ATRW: A Benchmark for Amur Tiger Re-identification in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 2590–2598. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Guo, L. Part-Pose Guided Amur Tiger Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Ma, Z.; Xia, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zi, J.; Xu, D.; Xu, F.; Su, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, F. A Serial Multi-Scale Feature Fusion and Enhancement Network for Amur Tiger Re-Identification. Animals 2024, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Islam, T.; Bin Azhar, M.A.H. Transformer-Based Models for Enhanced Amur Tiger Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 22nd World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Stará Lesná, Slovakia, 18–20 January 2024; pp. 000411–000416. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnett, E.; Holmberg, J.; Faryabi, S.P.; Li, A.; Ahmad, B.; Rashid, W.; Ostrowski, S. Determining Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia) Occupancy in the Pamir Mountains of Afghanistan. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, K.A.; Ahmad, S.; Armstrong, E.E.; Campana, M.G.; Ali, H.; Hameed, S.; Ullah, J.; Khan, B.U.; Nawaz, M.A.; Petrov, D.A. Next-Generation Snow Leopard Population Assessment Tool: Multiplex-PCR SNP Panel for Individual Identification from Faeces. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2025, 25, e14074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Shen, L.; Tian, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Tian, Q. Scalable Person Re-identification: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, S.; Liu, X. Overfitting Mechanism and Avoidance in Deep Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.06566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Li, F.-F. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, X.; Fang, L.; Huttunen, H. Adaptive L2 Regularization in Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 9601–9607. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

| Key-Point | Definition | Key-Point | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | left ear | 9 | right knee |

| 2 | right ear | 10 | right back paw |

| 3 | nose | 11 | left hip |

| 4 | right shoulder | 12 | left knee |

| 5 | right front paw | 13 | left back paw |

| 6 | left shoulder | 14 | root of tail |

| 7 | left front paw | 15 | center, mid point of 3 & 14 |

| 8 | right hip |

| Methods | Single-Cam | Cross-Cam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP | Top-1 | Top-5 | mAP | Top-1 | Top-5 | |

| CE [23] | 59.1 | 78.6 | 92.7 | 38.1 | 69.7 | 87.8 |

| Aligned-reID [23] | 64.8 | 81.2 | 92.4 | 44.2 | 73.8 | 90.5 |

| PPbM-a [23] | 74.1 | 88.2 | 96.4 | 51.7 | 76.8 | 91.0 |

| PPbM-b [23] | 72.8 | 89.4 | 95.6 | 47.8 | 77.1 | 90.7 |

| ResNet50+IFPM+LAEM [25] | 78.7 | 96.3 | 98.9 | — | — | — |

| ResNet50+ViT+MGN [26] | 83.4 | 92.3 | 94.9 | 43.6 | 79.4 | 85.7 |

| PPGNet(re-rank) [24] | 90.6 | 97.7 | 99.1 | 72.6 | 93.6 | 96.7 |

| PGNet-AL2(ours) | 91.3 | 98.9 | 99.7 | 71.3 | 95.4 | 97.7 |

| Methods | Single-Cam | Cross-Cam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP | Top-1 | Top-5 | mAP | Top-1 | Top-5 | |

| Baseline | 88.9 | 95.1 | 97.7 | 69.7 | 92.0 | 97.1 |

| +Pose Guided | 89.9 | 97.7 | 99.1 | 69.5 | 88.0 | 96.0 |

| +Pose Guided+AL2 | 91.3 | 98.8 | 99.7 | 71.3 | 95.4 | 97.7 |

| Methods | Single-Cam | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP | Top-1 | Top-5 | Top-10 | |

| Baseline | 92.7 | 97.4 | 98.4 | 98.6 |

| +AL2 | 94.5 | 98.6 | 98.9 | 99.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H. Enhancing Endangered Feline Conservation in Asia via a Pose-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Individual Identification. Diversity 2025, 17, 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120853

Xiao W, Zhang W, Liu H. Enhancing Endangered Feline Conservation in Asia via a Pose-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Individual Identification. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):853. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120853

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Weiwei, Wei Zhang, and Haiyan Liu. 2025. "Enhancing Endangered Feline Conservation in Asia via a Pose-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Individual Identification" Diversity 17, no. 12: 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120853

APA StyleXiao, W., Zhang, W., & Liu, H. (2025). Enhancing Endangered Feline Conservation in Asia via a Pose-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Individual Identification. Diversity, 17(12), 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120853