Contaminant Accumulation by Unionid Mussels: An Assemblage Level Assessment of Sequestration Functions Across Watersheds and Spatial Scales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

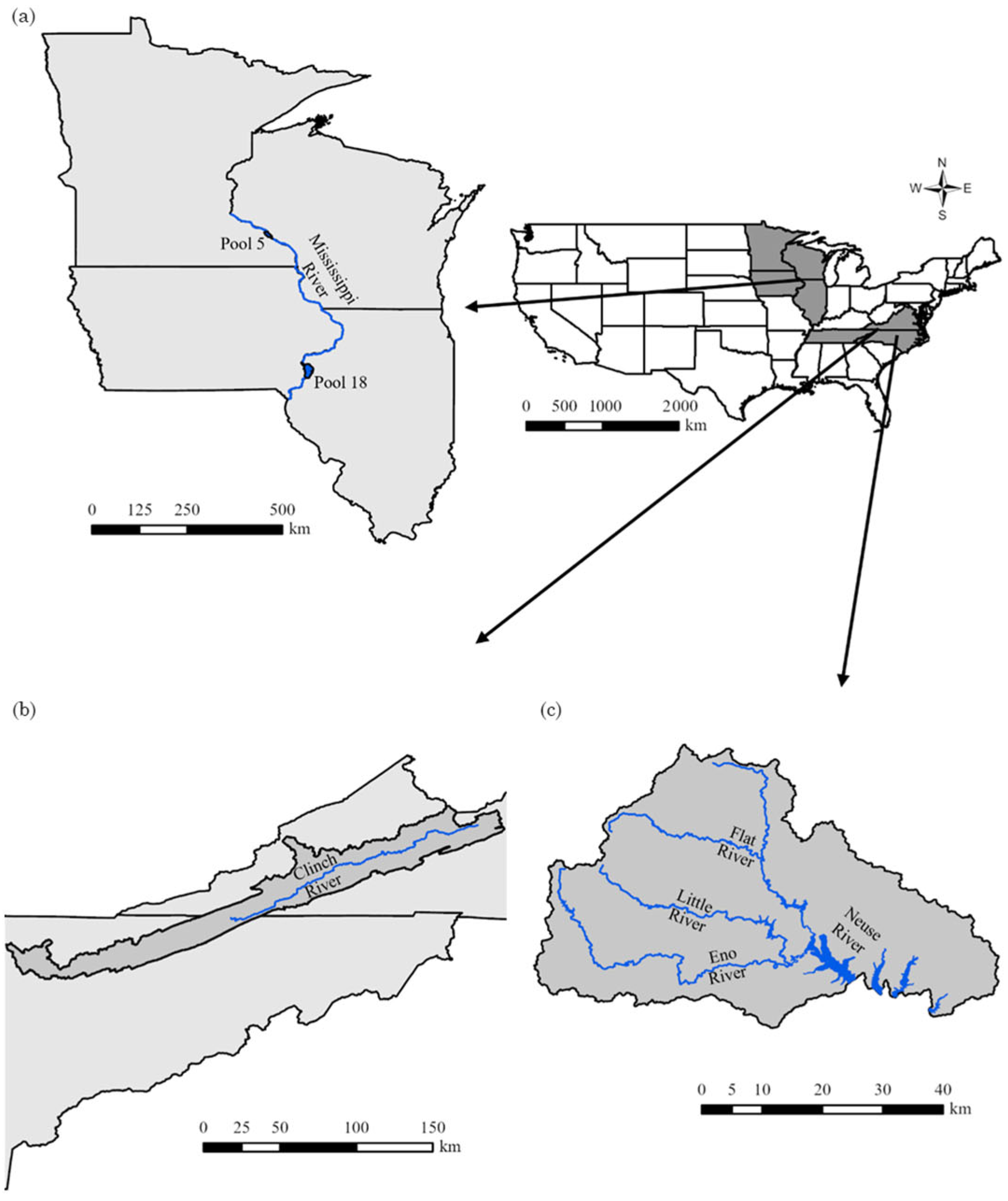

2.1. Upper Mississippi River Mussel Survey and Contaminant Data

2.2. Clinch River Mussel Survey and Contaminant Data

2.3. Upper Neuse River Mussel Survey and Contaminant Data

2.4. Contaminant Data and Sequestration Calculations

3. Results

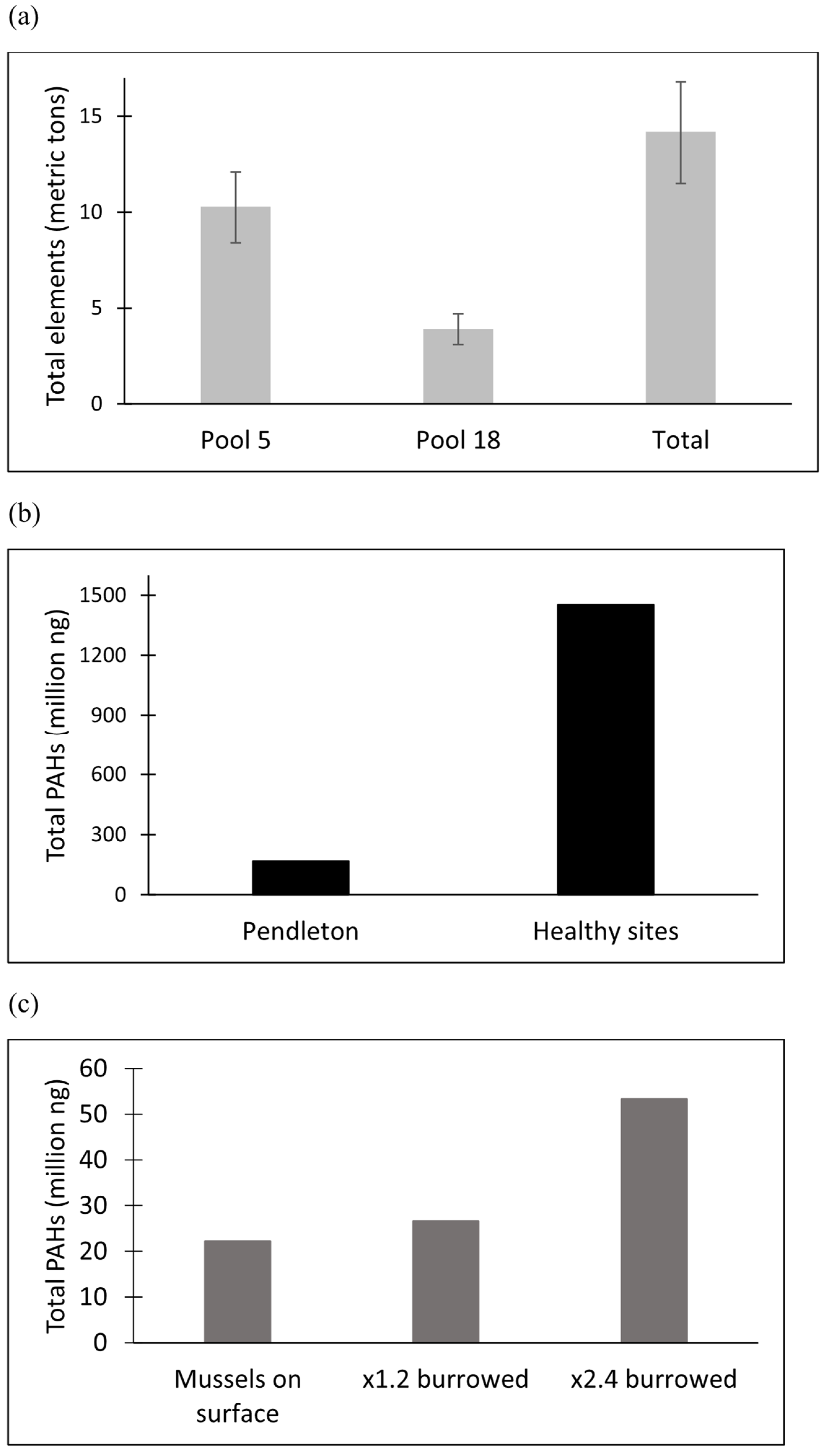

3.1. Upper Mississippi River

3.2. Clinch River

3.3. Upper Neuse River

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges of Using Existing Data to Estimate Contaminant Sequestration

4.2. Magnitude of Contaminant Sequestration

4.3. Contaminant Sequestration as an Ecosystem Function

4.4. Ecosystem Functions in an Era of Faunal Decline

4.5. Balancing Uncertainty and Decision-Making

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mace, G.M.; Norris, K.; Fitter, A.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Hoellein, T.J. Bivalve impacts in freshwater and marine ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2018, 49, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieritz, A.; Sousa, R.; Aldridge, D.C.; Douda, K.; Esteves, E.; Ferreira-Rodrıguez, N.; Mageroy, J.H.; Nizzoli, D.; Osterling, M.; Reis, J. A global synthesis of ecosystem services provided and disrupted by freshwater bivalve molluscs. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1967–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.L.; Hopper, G.W.; Kreeger, D.A.; Lopez, J.W.; Maine, A.N.; Sansom, B.J.; Schwalb, A.; Vaughn, C.C. Gains and gaps in knowledge surrounding freshwater mollusk ecosystem services. Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2023, 26, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Hakenkamp, C.C. The functional role of burrowing bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 2001, 46, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Gido, K.B.; Spooner, D.E. Ecosystem processes performed by unionid mussels in stream mesocosms: Species roles and effects of abundance. Hydrobiologia 2004, 527, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.K.; Cuffey, K.M. The functional role of native freshwater mussels in the fluvial benthic environment. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Nichols, J.S.; Spooner, D.E. Community and food web ecology of freshwater mussels. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2008, 27, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoellein, T.J.; Zarnoch, C.B.; Bruesewitz, D.A.; DeMartini, J. Contributions of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) to nutrient cycling in an urban river: Filtration, recycling, storage, and removal. Biogeochemistry 2017, 135, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turick, C.E.; Sexstone, A.J.; Bissonnette, G.K. Freshwater mussels as monitors of bacteriological water quality. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1988, 40, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.S.; Dodd, H.; Sassoubre, L.M.; Horne, A.J.; Boehm, A.B.; Luthy, R.G. Improvement of urban lake water quality by removal of Escherichia coli through the action of the bivalve Anodonta californiensis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.S.; Tommerdahl, J.P.; Boehm, A.B.; Luthy, R.G. Escherichia coli reduction by bivalves in an impaired river impacted by agricultural land use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11025–11033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, Y.; Weber, L.J.; Mynett, A.E.; Newton, T.J. Effects of substrate and hydrodynamic conditions on the formation of mussel beds in a large river. Freshw. Sci. 2006, 25, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, B.J.; Bennett, S.J.; Atkinson, J.F.; Vaughn, C.C. Emergent hydrodynamics and skimming flow over mussel covered beds in rivers. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringolf, R.B.; Heltsley, R.M.; Newton, T.J.; Eads, C.B.; Fraley, S.J.; Shea, D.; Cope, W.G. Environmental occurrence and reproductive effects of the pharmaceutical fluoxetine in native freshwater mussels. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.S.; Muller, C.E.; Morgan, R.R.; Luthy, R.G. Uptake of contaminants of emerging concern by the bivalves Anodonta californiensis and Corbicula fluminea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 9211–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreeger, D.A.; Gatenby, C.M.; Bergstrom, P.W. Restoration potential of several native species of bivalve molluscs for water quality improvement in Mid-Atlantic watersheds. J. Shellfish Res. 2018, 37, 1121–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ingersoll, C.G.; Greer, I.E.; Hardesty, D.K.; Ivey, C.D.; Kunz, J.L.; Brumbaugh, W.G.; Dwyer, F.J.; Roberts, A.D.; Augspurger, T.; et al. Chronic toxicity of copper and ammonia to juvenile freshwater mussels (Unionidae). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, W.G.; Bringolf, R.B.; Buchwalter, D.B.; Newton, T.J.; Ingersoll, C.G.; Wang, N.; Augspurger, T.; Dwyer, F.J.; Barnhart, M.C.; Neves, R.J.; et al. Differential exposure, duration, and sensitivity of unionoidean bivalve life stages to environmental contaminants. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2008, 27, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Ammonia—Freshwater (EPA-822-R-13-001); Office of Water. Office of Science and Technology: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/wqc/aquatic-life-criteria-ammonia (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Sharp, R.P.; Weil, C.; Bennett, E.M.; Pascual, U.; Arkema, K.K.; Brauman, K.A.; Bryant, B.P.; Guerry, A.D.; Haddad, N.M.; et al. Global modeling of nature’s contributions to people. Science 2019, 366, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L. What are freshwater mussels worth? Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2017, 20, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C.C.; Atkinson, C.L.; Julian, J.P. Drought-induced changes in flow regimes lead to long-term losses in mussel-provided ecosystem services. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubose, T.P.; Atkinson, C.L.; Vaughn, C.C.; Golladay, S.W. Drought-induced, punctuated loss of freshwater mussels alters ecosystem function across temporal scales. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, T.J.; Mayer, D.A.; Rogala, J.T.; Madden, S.S.; Gray, B.R. Responses of native freshwater mussels to remediation to remove polychlorinated biphenyl-contaminated sediments in the upper Hudson River. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2023, 33, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, B.L.; Polasky, S.; Brauman, K.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Finlay, J.C.; O’Neill, A. Linking water quality and well-being for improved assessment and valuation of ecosystem services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18619–18624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, T.J.; Zigler, S.J.; Rogala, J.T.; Gray, B.R.; Davis, M. Population assessment and potential functional roles of native mussels in the Upper Mississippi River. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2011, 21, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Ahlstedt, S.; Ostby, B.; Pinder, M.; Eckert, N.; Butler, R.; Hubbs, D.; Walker, C.; Hanlon, S.; Schmerfeld, J.; et al. Clinch River freshwater mussels upstream of Norris Reservoir, Tennessee and Virginia: A quantitative assessment from 2004–2009. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2014, 50, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Lane, T.; Ostby, B.; Beaty, B.; Ahlstedt, S.; Butler, R.; Hubbs, D.; Walker, C. Collapse of the Pendleton Island mussel fauna in the Clinch River, Virginia: Setting baseline conditions to guide recovery and restoration. Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2018, 21, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstedt, S.A.; Fagg, M.T.; Butler, R.S.; Connell, J.F.; Jones, J.W. Quantitative monitoring of freshwater mussel populations from 1979–2004 in the Clinch and Powell Rivers of Tennessee and Virginia, with miscellaneous notes on the fauna. Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2016, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.C.; Krstolic, J.L.; Ostby, B.J.K. Influences of water and sediment quality and hydrologic processes on mussels in the Clinch River. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2014, 50, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.E.; Zipper, C.E.; Jones, J.W.; Franck, C.T. Water and sediment quality in the Clinch River, Virginia and Tennessee, USA, over nearly five decades. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2014, 50, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, J.M.; Bergeron, C.M.; Cope, W.G.; Lazaro, P.R.; Leonard, J.A.; Shea, D. Assessing toxicity of contaminants in riverine suspended sediments to freshwater mussels. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, W.G.; Bergeron, C.M.; Archambault, J.M.; Jones, J.W.; Beaty, B.; Lazaro, P.R.; Shea, D.; Callihan, J.L.; Rogers, J.J. Understanding the influence of multiple pollutant stressors on the decline of freshwater mussels in a biodiversity hotspot. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 144757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.A.; Bergeron, C.M.; Archambault, J.M.; Unrine, J.; Jones, J.W.; Beaty, B.; Shea, D.; Lazaro, P.R.; Callihan, J.L.; Rogers, J.J.; et al. A unionid mussel biodiversity hotspot experiencing unexplained declines: Evaluating the influence of chemical stressors with caged juveniles. Diversity 2025, 17, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.F.; Bogan, A.E.; Pollock, K.H.; Devine, H.A.; Gustufson, L.L.; Eads, C.B.; Russel, P.P.; Anderson, E.F. Distribution of Freshwater Mussel Populations in Relationship to Crossing Structures. Final Report Submitted to the North Carolina Department of Transportation (HWY-2003-02). 2003. Available online: https://connect.ncdot.gov/projects/research/RNAProjDocs/2001-10FinalReport.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Levine, J.F.; Cope, W.G.; Bogan, A.E.; Stoskopf, M.; Gustafson, L.L.; Showers, B.; Shea, D.; Eads, C.B.; Lazaro, P.; Thorsen, W.; et al. Assessment of the Impact of Highway Runoff on Freshwater Mussels in North Carolina Streams. Final Report Submitted to the North Carolina Department of Transportation (2001-13. FHWA/NC/2004-03). 2005. Available online: https://connect.ncdot.gov/projects/research/RNAProjDocs/Final_Report_2001-13.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Hastie, L.C.; Cooksley, S.L.; Scougall, F.; Young, M.R.; Boon, P.J.; Gaywood, M.J. Applications of extensive survey techniques to describe freshwater pearl mussel distribution and macrohabitat in the River Spey, Scotland. River Res. Appl. 2004, 20, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USFWS (US Fish and Wildlife Service). Freshwater Mussel Survey Protocol for the Southeastern Atlantic Slope and Northeastern Gulf Drainages in Florida and Georgia; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services and Fisheries Resources Offices: Athens, GA, USA; Georgia Department of Transportation, Office of Environment and Location: Athens, GA, USA, 2008; 39p. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Final-Mussel-Survey-Protocol-FL-GA-April-2008.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Eads, C.B.; Levine, J.F. Vertical migration and reproductive patterns of a long-term brooding freshwater mussel, Villosa constricta (Bivalvia: Unionidae) in a small Piedmont stream. Walkerana J. Freshw. Mollusk Conserv. Soc. 2013, 16, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, J.M.; Prochazka, S.T.; Cope, W.G.; Shea, D.; Lazaro, P.R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface waters, sediments, and unionid mussels: Relation to road crossings and implications for chronic mussel exposure. Hydrobiologia 2018, 810, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R. Survey design for detecting rare freshwater mussels. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2006, 25, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, D.L.; Smock, L.A. Distribution, age structure, and movements of the freshwater mussel Elliptio complanata (Mollusca; Unionidae) in a headwater stream. J. Freshw. Ecol. 1995, 10, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, R.J.; Cope, W.G.; Kwak, T.J.; Eads, C.B. Short-term effects of small dam removal on a freshwater mussel assemblage. Walkerana J. Freshw. Mollusk Conserv. Soc. 2013, 16, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, J.M. Contaminant-Related Ecosystem Functions and Services of Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) and Public Views on Nature’s Contributions to Water Quality. Ph.D. Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/resolver/1840.20/37311 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Strayer, D.L.; Malcom, H.M. Long-term responses of native bivalves (Unionidae and Sphaeriidae) to a Dreissena invasion. Freshw. Sci. 2018, 37, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollard, I.; Aldridge, D.C. Declines in freshwater mussel density, size and productivity in the River Thames over the past half century. J. Anim. Ecol. 2022, 92, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Smith, D.R. A Guide to Sampling Freshwater Mussel Populations; Monograph 8; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hornbach, D.J.; Deneka, T. A comparison of a qualitative and a quantitative collection method for examining freshwater mussel assemblages. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 1996, 15, 587–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, S.L.; Wiener, J.G.; Atchison, G.J. Cadmium and mercury in sediment and burrowing mayfly nymphs (Hexagenia) in the upper Mississippi River, USA. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1995, 28, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.G.; Jackson, G.A.; May, T.W.; Cole, B.P. Longitudinal distribution of trace elements (As, Cd, Cr, Hg, Pb, and Se) in fishes and sediments in the Upper Mississippi River. In Contaminants in the Upper Mississippi River; Wiener, J.G., Anderson, R.V., McConville, D.R., Eds.; Butterworth Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, C.L.; Sansom, B.J.; Vaughn, C.C.; Forshay, K.J. Consumer aggregations drive nutrient dynamics and ecosystem metabolism in nutrient-limited systems. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Mussels for Clean Water Initiative; Partnership for the Delaware Estuary: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2017; Available online: https://delawareestuary.org/science-and-research/mussels-clean-water-initiative-mucwi-2/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Philadelphia Today. Can Freshwater Mussels Help Solve Delaware River’s Pollution Problem? A Team at PWD Seeks Answers; Philadelphia Today, American Community Journals, LLC.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://philadelphia.today/2024/11/freshwater-mussels-delaware-river-pollution/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Farris, J.L.; Van Hassel, J.H. Freshwater Bivalve Ecotoxicology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, W.N.; Meadow, J.P. Environmental Contaminants in Biota: Interpreting Tissue Concentrations, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; p. 732. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, D.E.; Vaughn, C.C. Context-dependent effects of freshwater mussels on stream benthic communities. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2018, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovic, D.; Carrizo, S.; Freyhof, J.; Cid, N.; Lengyel, S.; Scholz, M.; Darwall, W. Europe’s freshwater biodiversity under climate change: Distribution shifts and conservation needs. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Berg, D.J. Predicting the effects of climate change on population connectivity and genetic diversity of an imperiled freshwater mussel, Cumberlandia monodonta (Bivalvia: Margaritiferidae) in riverine systems. Global Change Biol. 2017, 23, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, H.S.; Vaughn, C.C. Effects of reservoir management on abundance, condition, parasitism and reproductive traits of downstream mussels. River Res. Appl. 2011, 27, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augspurger, T.P.; Keller, A.E.; Black, M.C.; Cope, W.G.; Dwyer, F.J. Water quality guidance for the protection of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from ammonia exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Kunz, J.L.; Cleveland, D.M.; Steevens, J.A.; Hammer, E.J.; Van Genderen, E.; Ryan, A.C.; Schlekat, C.E. Evaluation of acute and chronic toxicity of nickel and zinc to 2 sensitive freshwater benthic invertebrates using refined testing methods. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2020, 39, 2256–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. Uncertainty, complexity, and post-normal science. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1993, 13, 1881–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscough, J.; Wilson, M.; Kenter, J.O. Ecosystem services as a post-normal field of science. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FMCS (Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society). A national strategy for the conservation of freshwater mollusks. Freshw. Mollusk Biol. Conserv. 2016, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, B.; Bouchard, R.W., Jr.; Dietz, R.; Hornbach, D.; Monson, P.; Sietman, B.; Wasley, D. Freshwater mussels, ecosystem services, and clean water regulation in Minnesota: Formulating an effective conservation strategy. Water 2023, 15, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olander, L.; Johnston, R.J.; Tallis, H.; Kagan, J.; Maguire, L.; Polasky, S.; Urban, D.; Boyd, J.; Wainger, L.; Palmer, M. Best Practices for Integrating Ecosystem Services into Federal Decision Making. In National Ecosystem Services Partnership; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/sites/default/files/publications/es_best_practices_fullpdf_0.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Olander, L.; Johnston, R.J.; Tallis, H.; Kagan, J.; Maguire, L.; Polasky, S.; Urban, D.; Boyd, J.; Wainger, L.; Palmer, M. Benefit relevant indicators: Ecosystem services measures that link ecological and social outcomes. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushet, D.M.; van der Burg, M.P.; Anteau, M.J. Assessing conservation and management actions with ecosystem services better communicates conservation value to the public. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 2022, 13, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, N.; Munday, M.; Durance, I. The challenge of valuing ecosystem services that have no material benefits. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 44, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olander, L.; Maltby, L. Mainstreaming ecosystem services into decision making. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.P.; Jackson, S.; Tharme, R.E.; Douglas, M.; Flotemersch, J.E.; Zwarteveen, M.; Lokgariwar, C.; Montoya, M.; Wali, A.; Tipa, G.T.; et al. Understanding rivers and their social relations: A critical step to advance environmental water management. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Site | Species | Tissue Concentration | Tissue Mass | Number of Mussels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Mississippi River | Total Elements (ug/g dry weight) | Dry weight (g) | Population Estimate (Quantitative) | |

| Pool 5 | ||||

| Amblema plicata | 9598 | 2.50 | 190 million (±37 million) | |

| Fusconaia flava | 12,371 | 1.90 | ||

| Lampsilis cardium | 12,102 | 9.90 | ||

| Pool-wide mean | 11,357 | 4.77 | ||

| Pool 18 | ||||

| Amblema plicata | 10,385 | 3.44 | 212 million (±43 million) | |

| Obliquaria reflexa | 6284 | 0.81 | ||

| Quadrula quadrula | 9781 | 1.88 | ||

| Pool-wide mean | 8817 | 2.04 | ||

| Clinch River | Total PAHs (ng/g dry weight) | Wet weight (g) | Population Estimate (Site-specific quantitative) | |

| Pendleton Island | Actinonaias pectorosa | 852 | 42.83 | 55,500 |

| Unpolluted Sites | Actinonaias pectorosa | 239 | 1,704,185 | |

| Upper Neuse River | Total PAHs (ng/g dry weight) | Wet weight (g) (including shell) | Population Estimate (Qualitative) | |

| Combined Sites | Elliptio complanata | 182 | 43.85 | 79,729 |

| Pool 5 | Pool 18 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | Amblema plicata | Fusconaia flava | Lampsilis cardium | Amblema plicata | Obliquaria reflexa | Quadrula quadrula |

| Aluminum (Al) | 125.25 (9.80) | 160.77 (10.38) | 175.96 (11.44) | 178.84 (13.77) | 202.42 (35.03) | 209.27 (27.29) |

| Arsenic (As) | 5.57 (0.16) | 4.87 (0.14) | 5.44 (0.19) | 5.00 (0.26) | 5.13 (0.11) | 3.65 (0.19) |

| Barium (Ba) | 260.32 (29.85) | 348.12 (17.98) | 407.72 (56.25) | 358.12 (52.34) | 103.91 (2.85) | 220.68 (22.76) |

| Beryllium (Be) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00) |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 0.37 (0.02) | 0.41 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.03) | 0.42 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.64 (0.05) |

| Cobalt (Co) | 0.51 (0.03) | 0.63 (0.02) | 0.50 (0.02) | 0.65 (0.05) | 0.54 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.15) |

| Chromium (Cr) | 1.03 (0.10) | 1.92 (0.12) | 0.80 (0.05) | 1.61 (0.11) | 1.44 (0.13) | 1.83 (0.22) |

| Copper (Cu) | 9.71 (1.07) | 27.98 (5.10) | 6.01 (0.97) | 18.34 (2.34) | 28.81 (3.44) | 23.24 (3.91) |

| Iron (Fe) | 1461.69 (83.27) | 2217.69 (107.06) | 1143.56 (66.11) | 1285.87 (121.55) | 886.28 (78.47) | 1458.93 (120.11) |

| Mercury (Hg) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.00) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.05 (0.00) |

| Potassium (K) | 2266.60 (82.29) | 1797.27 (79.88) | 1955.76 (93.10) | 1812.62 (59.14) | 2455.45 (46.56) | 2608.96 (109.96) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 1572.19 (63.42) | 1735.52 (57.46) | 1925.58 (97.08) | 1678.59 (122.44) | 1227.65 (25.17) | 1555.87 (43.50) |

| Manganese (Mn) | 3329.98 (434.89) | 5435.68 (260.13) | 5586.79 (600.54) | 4300.69 (604.57) | 904.45 (42.82) | 3111.51 (386.54) |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.30 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) |

| Nickel (Ni) | 1.41 (0.10) | 2.06 (0.08) | 1.50 (0.11) | 1.81 (0.16) | 1.79 (0.12) | 1.32 (0.09) |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.38 (0.01) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.59 (0.05) | 0.58 (0.03) |

| Antimony (Sb) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) |

| Selenium (Se) | 3.26 (0.12) | 3.34 (0.06) | 2.66 (0.09) | 2.97 (0.12) | 4.14 (0.08) | 3.54 (0.10) |

| Silicon (Si) | 278.97 (32.76) | 404.09 (39.85) | 451.65 (21.26) | 378.91 (31.43) | 352.58 (57.85) | 356.44 (55.01) |

| Strontium (Sr) | 85.43 (9.81) | 110.37 (5.01) | 111.52 (13.41) | 84.50 (10.24) | 24.73 (1.00) | 47.86 (3.44) |

| Vanadium (V) | 0.67 (0.03) | 0.70 (0.04 | 0.81 (0.06) | 0.49 (0.04) | 1.00 (0.10) | 0.65 (0.09) |

| Zinc (Zn) | 194.45 (9.56) | 118.34 (3.21) | 324.43 (26.36) | 275.06 (26.69) | 82.88 (1.50) | 174.68 (4.93) |

| Sum | 9598.13 | 12,370.54 | 12,101.64 | 10,385.38 | 6284.39 | 9780.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Archambault, J.M.; Cope, W.G.; Newton, T.J.; Dunn, H.L.; Eads, C.B.; Jones, J.W.; Cope, W.R. Contaminant Accumulation by Unionid Mussels: An Assemblage Level Assessment of Sequestration Functions Across Watersheds and Spatial Scales. Diversity 2025, 17, 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120855

Archambault JM, Cope WG, Newton TJ, Dunn HL, Eads CB, Jones JW, Cope WR. Contaminant Accumulation by Unionid Mussels: An Assemblage Level Assessment of Sequestration Functions Across Watersheds and Spatial Scales. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):855. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120855

Chicago/Turabian StyleArchambault, Jennifer M., W. Gregory Cope, Teresa J. Newton, Heidi L. Dunn, Chris B. Eads, Jess W. Jones, and W. Robert Cope. 2025. "Contaminant Accumulation by Unionid Mussels: An Assemblage Level Assessment of Sequestration Functions Across Watersheds and Spatial Scales" Diversity 17, no. 12: 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120855

APA StyleArchambault, J. M., Cope, W. G., Newton, T. J., Dunn, H. L., Eads, C. B., Jones, J. W., & Cope, W. R. (2025). Contaminant Accumulation by Unionid Mussels: An Assemblage Level Assessment of Sequestration Functions Across Watersheds and Spatial Scales. Diversity, 17(12), 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120855