Ethnobotanical Assessment of the Diversity of Wild Edible Plants and Potential Contribution to Enhance Sustainable Food Security in Makkah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

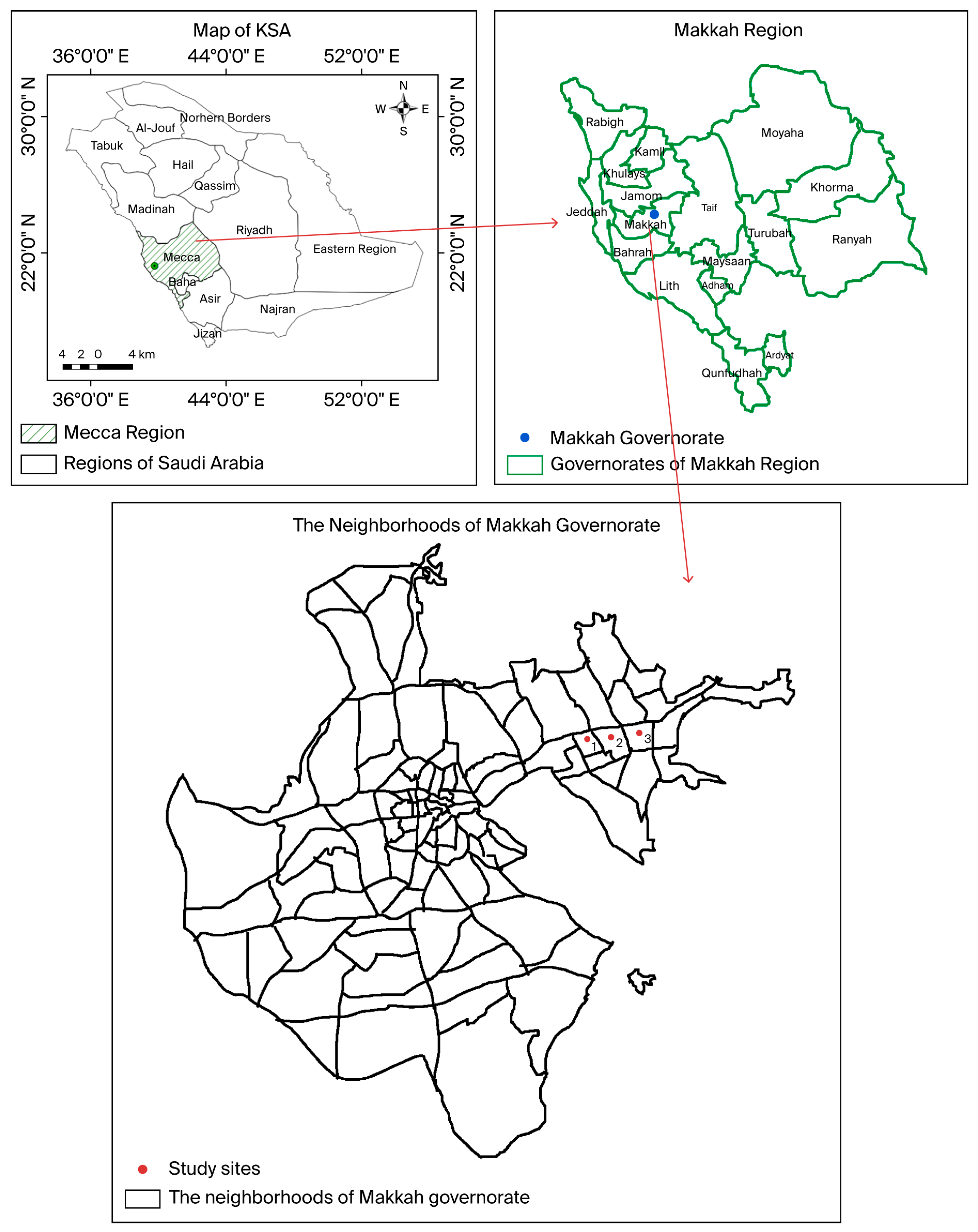

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Collection and Identification of Plant Specimens

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Preference Ranking

2.6. Threat Rankings by Priority

2.7. Comparative Studies on Literature Resviews

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wild Edible Plant Knowledge Distribution Among Sociodemographic Groups

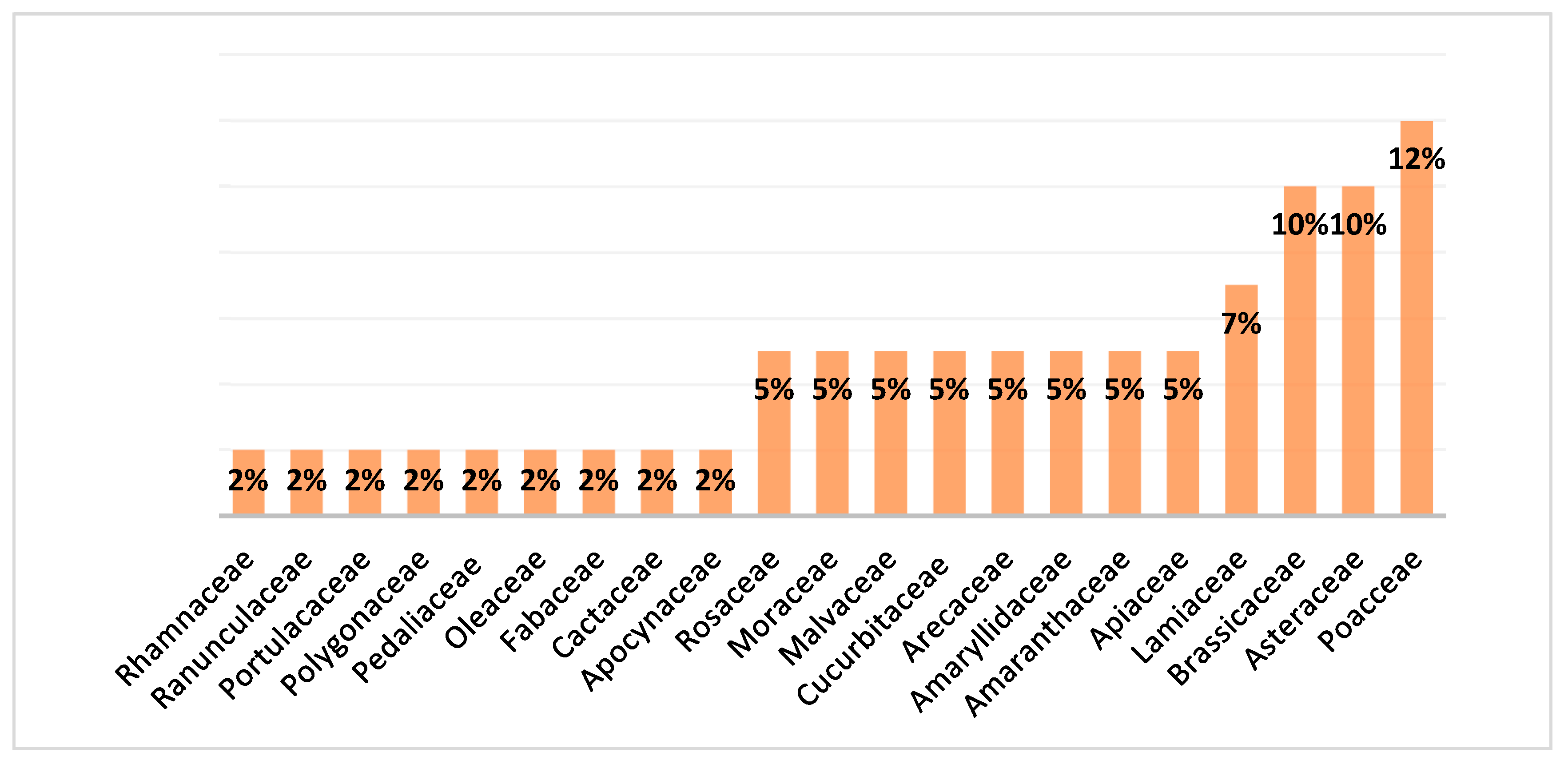

3.2. Taxonomic Diversity of Wild Edible Plants

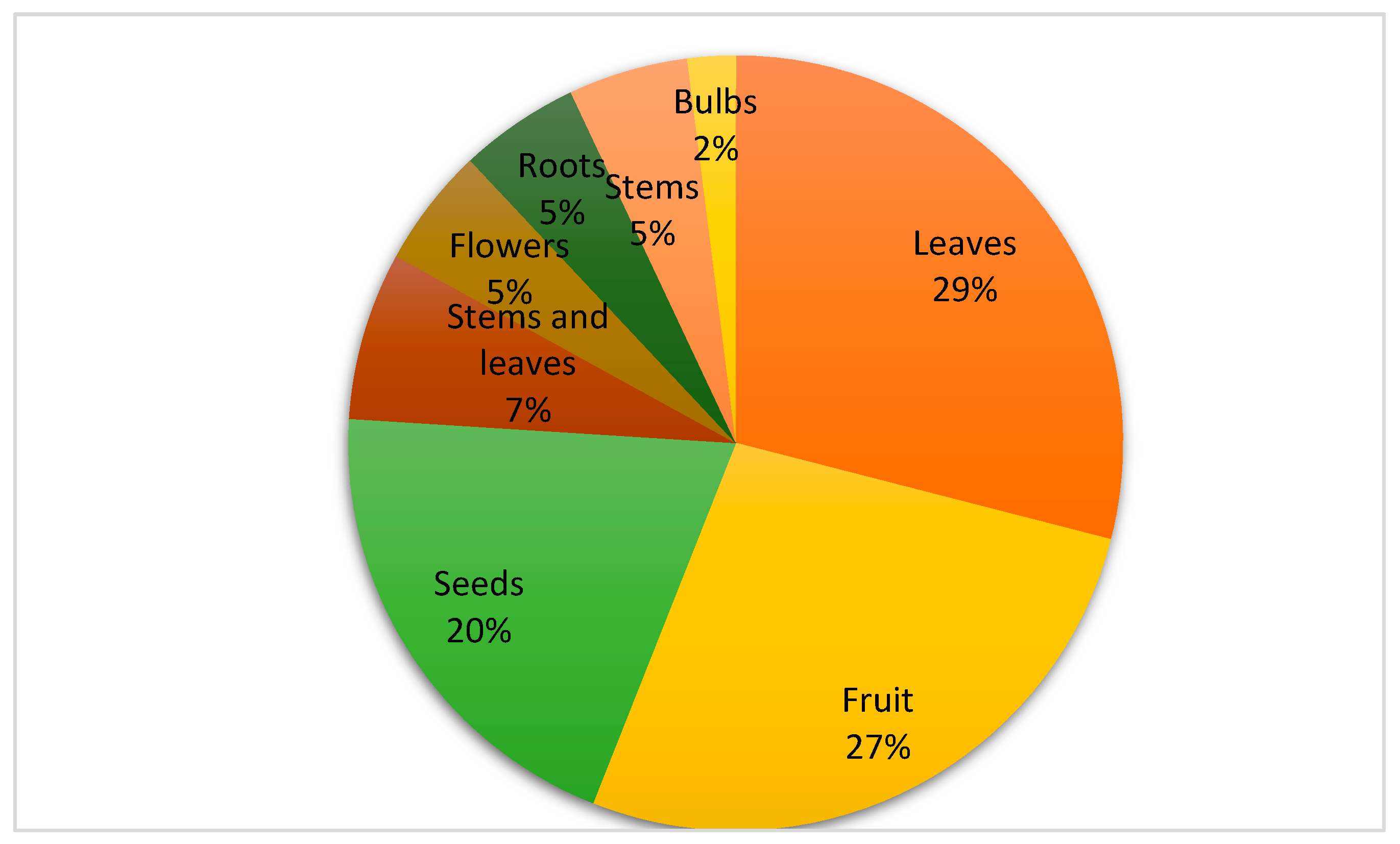

3.3. Edible Parts of Wild Edible Plants

3.4. Methods of Consuming Edible Wild Plants

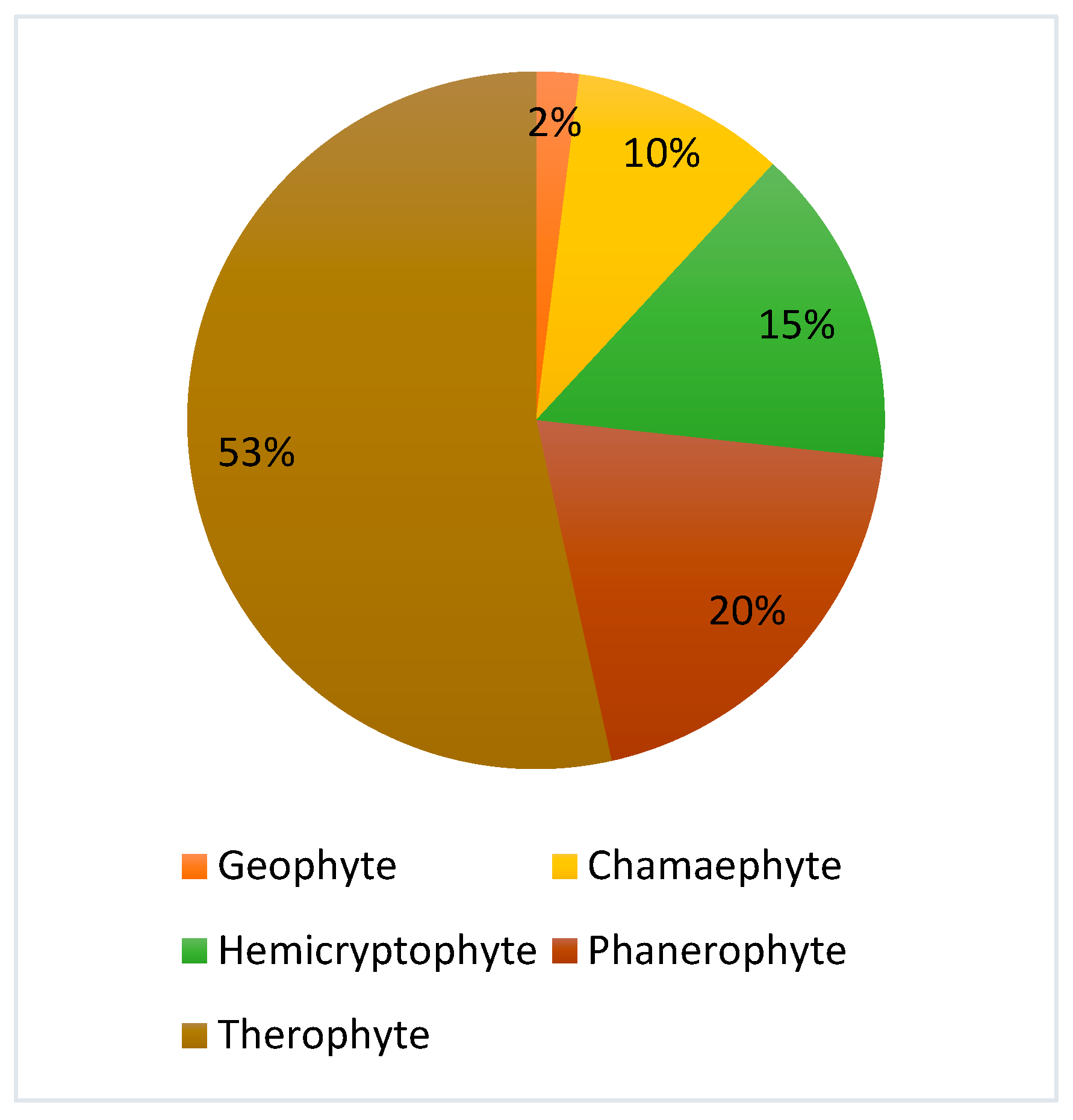

3.5. Wild Edible Plant Life Form

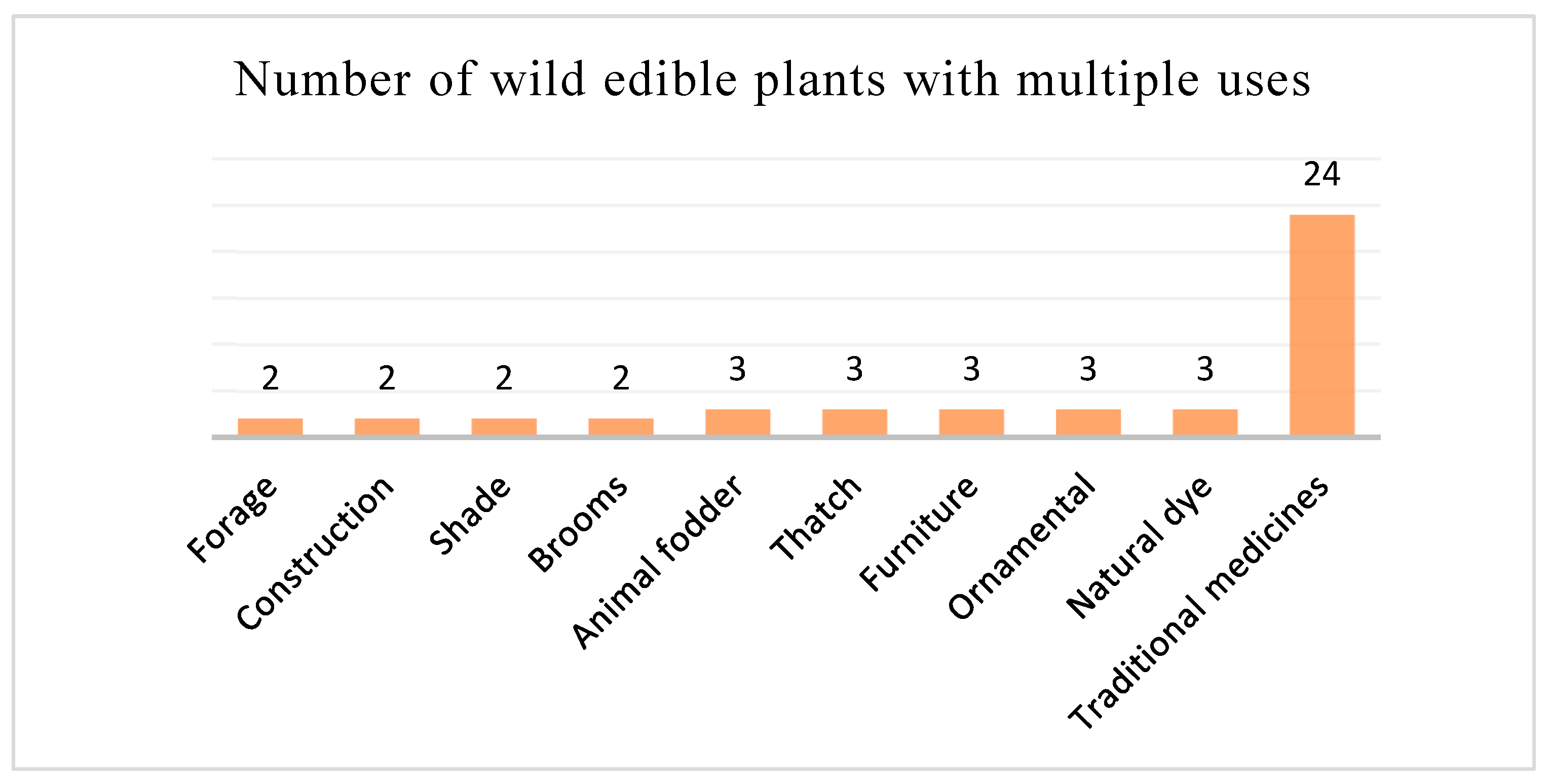

3.6. Additional Applications for Edible Wild Plants

3.7. Preference Ranking of Wild Edible Plants

3.8. Wild Edible Plant Threats and Conservation

3.9. Comparative Study

3.10. Novel Ethnobotanical Findings

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KSA | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. |

| WEPs | Wild edible plants. |

| WEP | Wild edible plant. |

| F | Frequencies. |

| RFC | Relative frequency of citation. |

References

- Martin, G.J. Ethnobotany: A Method Manual. A ‘People and Plants’ Conservation Manual; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Balick, M.J. Plants, people and culture: The science of ethnobotany (New York Botanical Garden) and P.A. Cox (Brigham Young University). Scientific American Library, New York. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 60, 428–429. [Google Scholar]

- Kidane, L.; Kejela, A. Food security and environment conservation through sustainable use of wild and semi-wild edible plants: A case study in Berek Natural Forest, Oromia special zone, Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Ahmad, M.; Haroon, N.; Shaheen, S.; Ahmad, M.; Haroon, N. Edible wild plants: A solution to overcome food insecurity. In Edible Wild Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw, A.; Lulekal, E.; Bekele, T.; Debella, A.; Tessema, S.; Meresa, A.; Debebe, E. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants and implications for food security. Trees For. People 2023, 14, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Schueckler, A. Use and Potential of Wild Plants in Farm Households; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Balemie, K.; Kebebew, F. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Derashe and Kucha Districts, South Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.; Thilsted, S.H.; Ickowitz, A.; Termote, C.; Sunderland, T.; Herforth, A. Improving diets with wild and cultivated biodiversity from across the landscape. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Rana, Z.H.; Islam, S.N.; Akhtaruzzaman, M. Comparative assessment of nutritional composition, polyphenol profile, antidiabetic and antioxidative properties of selected edible wild plant species of Bangladesh. Food Chem. 2020, 320, 126646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Jan, S.A.; Javed, M.; Shaheen, R.; Khan, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Safi, S.Z.; Imran, M. Nutritional composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of selected wild edible plants. J. Food Biochem. 2016, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, O.O.; Kayode, J. Ethnomedicinal assessment of wild edible plants in Ijesa Region, Osun State, Nigeria. Bull. Pure Appl. Sci. 2018, 37, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokganya, M.; Tshisikhawe, M. Medicinal uses of selected wild edible vegetables consumed by Vhavenda of the Vhembe District Municipality, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhuo, J.; Liu, B.; Long, C. Eating from the wild: Diversity of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-La Region, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagh, Y.K. Poverty, food security and human security. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2002, 3, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elneel, F.A. Food exports and its contribution to the sudan economic development in the light of COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from simultaneous equation model (1974–2019). In From Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: Mapping the Transitions; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-07-2019-world-hunger-is-still-not-going-down-after-three-years-and-obesity-is-still-growing-un-report (accessed on 1 March 2025).[Green Version]

- Al-Adhaileh, M.H.; Aldhyani, T.H. Artificial intelligence framework for modeling and predicting crop yield to enhance food security in Saudi Arabia. Peer J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dubey, R.K.; Bundela, A.K.; Abhilash, P.C. The Trilogy of Wild Crops, Traditional Agronomic Practices, and Un-Sustainable Development Goals. Agronomy 2020, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Phil Trans. R. Soc. B. 2010, 365, 2913–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanash, N. Biocultural Diversity and Integrated Health Care in Madagascare; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw, Z.; Tadesse, M. Prospects for sustainable use & development of wild food plants in Ethiopia. Econ. Bot. 2001, 55, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Alfarhan, A.; Al-Turki, T.; Basahy, A. Flora of Jizan Region. King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Riyadh. Saudi Arab. 2005, 1, 1–523. [Google Scholar]

- Masrahi, Y.; AL-Huqail, A.; AL-Turki, T.; Thomas, J. Odyssea mucronata, Sesbania sericea, and Sesamum alatum–new discoveries for the flora of Saudi Arabia. Turk. J. Bot. 2012, 36, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eisawi, D.M.; Al-Ruzayza, S. The flora of holy Mecca district, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 7, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsherif, E.A. Ecological studies of Commiphora genus (myrrha) in Makkah Region, Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, T.M.; Al-Yasi, H.M.; Fadl, M.A. Vegetation zonation along the desert-wetland ecosystem of Taif Highland, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3374–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaidarous, A.A.; Osman, H.E.; Galal, T.M.; El-Morsy, M.H. Vegetation–environment relationship and floristic diversity of wadi Al-sharaea, Makkah Province, Saudi Arabia. Rendiconti Lincei. Sci. Fis. E Nat. 2022, 33, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Alshareef, A. Geography of Saudi Arabia South-West of the Kingdom; Dar Almerikh: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1984; Volume 2, pp. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Said, M. Traditional Medicinal Plants of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Amer. J. Chin. Med. 1993, 21, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Mossa, J.; Al-Said, M.; Al-Yahya, M. Medicinal plant diversity in the flora of Saudi Arabia 1: A report on seven plant families. Fitotherapia 2004, 75, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turki, T.; Al-Olayan, H. Contribution to the Flora of Saudi Arabia: Hail Region. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. Riyadh. Saudi Arab. 2003, 10, 190–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, M.A.; Kasem, W.T.; Shalabi, L.F. Floristic diversity and vegetation-soil correlations in Wadi Qusai, Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2018, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkolibi, F.M. Possible effects of global warming on agriculture and water resources in Saudi Arabia: Impacts and responses. Clim. Chang. 2002, 54, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.B.; Hussein, M.H.; Magram, S.F.; Barua, R. Impact of climate parameters on agriculture in Saudi Arabia: Case study of selected crops. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Impacts Responses 2011, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbed, A.; Kumar, L.; Shabani, F. Climate change impacts on date palm cultivation in Saudi Arabia. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 155, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I.; Khan, M.R. Impact of climate change on food security in Saudi Arabia: A roadmap to agriculture-water sustainability. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazroui, M.; Islam, M.N.; Saeed, S.; Alkhalaf, A.K.; Dambul, R. Assessment of uncertainties in projected temperature and precipitation over the Arabian Peninsula using three categories of CMIP5 multimodel ensembles. Earth Syst. Environ. 2017, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waha, K.; Krummenauer, L.; Adams, S.; Aich, V.; Baarsch, F.; Coumou, D.; Mengel, M. Climate change impacts in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region and their implications for vulnerable population groups. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1623–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustainability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, M.R.; Sulphey, M.M. Food security as a prelude to sustainability: A case study in the agricultural sector, its impacts on the Al Kharj community in The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, L. How does grazing exclusion influence plant productivity and community structure in alpine grasslands of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mseddi, K.; Alghamdi, A.; Abdelgadir, M.; Sharawy, S. Phytodiversity distribution in relation to altitudinal gradient in Salma Mountains–Saudi Arabia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqethami, A.; Hawkins, J.A.; Teixidor-Toneu, I. Medicinal plants used by women in Mecca: Urban, Muslim and gendered knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Qari, S.H.; Alqethami, A.; Qumsani, A.T. Ethnomedicinal evaluation of medicinal plants used for therapies by men and women in rural and urban communities in Makkah district. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Alghafari, Y. Temperature, precipitation and relative humidity fluctuation of Makkah Al Mukarramah, kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1985–2016). Trans. Mach Learn. Artif. Intell. 2018, 6, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 5th ed.; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, S.A. Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; Ministry of Agriculture and Water: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, C. Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Alsherif, E.A.; Ayesh, A.M.; Allogmani, A.S.; Rawi, S.M. Exploration of wild plants wealth with economic importance tolerant to difficult conditions in Khulais Governorate, Saudi Arabia. Sci. Res. Essays 2012, 7, 3903–3913. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, A.K.; Al-Rowaily, S.L.; Faisal, M.; Alatar, A.A.; El-Bana, M.I.; Assaeed, A.M. Nutritive value and antioxidant activity of some edible wild fruits in the Middle East. J. Med. Plant Res. 2013, 7, 938–946. [Google Scholar]

- Alfarnan, A.H.; Al-Farraj, M.M.; Hajar, A.S. Wild Edible Plants in Saudi Arabia; Springer Nature: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, A.K.; Alatar, A.A.; Thomas, J.; Faisal, M.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Krzywinski, K. Compatibility and complementarity of indigenous and scientific knowledge of wild plants in the highlands of southwest Saudi Arabia. J. For. Res. 2014, 25, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant Diversity of Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://plantdiversityofsaudiarabia.info/community-impact/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Al-Fatimi, M. Wild edible plants traditionally collected and used in southern Yemen. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hussain, S.T.; Muhammad, S.; Khan, S.; Hussain, W.; Pieroni, A. Ethnobotany for food security and ecological transition: Wild food plant gathering and consumption among four cultural groups in Kurram District, NW Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbessa, B.; Lulekal, E.; Debella, A.; Hymete, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Dibatie district, Metekel zone, Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, western Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashagre, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Kelbessa, E. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Burji District, Segan area zone of southern nations, nationalities and peoples region (SNNPR), Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, T.; Molla, E. Study on the diversity and use of wild edible plants in Bullen district Northwest Ethiopia. J. Bot. 2017, 2017, 8383468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Langenberger, G.; Sauerborn, J. A comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, Sw China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyakoojo, C.; Tugume, P. Traditional use of wild edible plants in the communities adjacent Mabira Central Forest Reserve, Uganda. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, N.M.; Al-Qahtani, S.J.; Alzaben, A.S. The association between dietary patterns and socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics: A sample of Saudi Arabia. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2021, 9, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariod, A.; Tahir, H.E.; Salama, S. Food consumption patterns in Saudi Arabia. In Food and Nutrition Security in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Vol. 2: Macroeconomic Policy and Its Implication on Food and Nutrition Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 303–319. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Alghamdi, B.A.; Alotaibi, N.M.; Alotaibi, M.O.; Al-Qthanin, R.N.; Al-Shalan, H.Z. Role of Date Palm to Food and Nutritional Security in Saudi Arabia. In Food and Nutrition Security in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Vol. 2: Macroeconomic Policy and Its Implication on Food and Nutrition Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahib, W.; Marshall, R.J. The fruit of the date palm: Its possible use as the best food for the future? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2003, 54, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farsi, M.A.; Lee, C.Y. Nutritional and functional properties of dates: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alqurashi, R.M.; Al-Khayri, J.M. Bioactive compounds of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). In Bioactive Compounds in Underutilized Fruits and Nuts. Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Murthy, H., Bapat, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mssallem, M.Q. The role of date palm fruit in improving human health. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2020, 14, OE01–OE06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickavasagan, A.; Mohamed, E.M.; Sukumar, E. Dates: Production, Processing, Food, and Medicinal Values; CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tengberg, M. Beginnings and early history of date palm garden cultivation in the Middle East. J. Arid. Environ. 2012, 86, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, S.W.; Ahmad, M.; Manzoor, M.; Waheed, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Ullah, R.; Pieroni, A.; Zhang, L.; Sulaiman, N.; Alrhmoun, M. The nexus between ecology of foraging and food security: Cross-cultural perceptions of wild food plants in Kashmir Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulekal, E.; Asfaw, Z.; Kelbessa, E.; Van Damme, P. Wild edible plants in Ethiopia: A review on their potential to combat food insecurity. Afr. Focus 2011, 24, 71–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Al-Shafie, J.H.; Elgharabah, W.A.; Kherfan, F.A.; Qarariah, K.H.; Khdair, I.S.; Soos, I.M.; Musleh, A.A.; Isa, B.A. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine (Northern West Bank): A comparative study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, H.; Sharma, Y.P.; Manhas, R.K.; Kumar, K. Traditionally used wild edible plants of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, D.; Masresha, G.; Lulekal, E.; Alemu, A. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Metema and Quara districts, Northwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2025, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, N.K.E.M.; Ali, A.H. Wild food trees in Eastern Nuba mountains, Sudan: Use, diversity, and threatening factors. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 2014, 115, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Lu, X.; Lin, F.; Naeem, A.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants used by Dulong people in northwestern Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Huang, X.; Bin, Z.; Yu, B.; Lu, Z.; Hu, R.; Long, C. Wild edible plants and their cultural significance among the Zhuang ethnic group in Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Luo, B.; Long, C. Wild edible plants of the Yao people in Jianghua, China: Plant-associated traditional knowledge and practice vital for food security and ecosystem service. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, M.; Aziz, M.A.; Pieroni, A.; Nazir, A.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Kangal, A.; Ahmad, K.; Abbasi, A.M. Edible wild plant species used by different linguistic groups of Kohistan Upper Khy- ber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERTAŞ, F.; ÇELİK, S. A Mixed Research on Determining the Edible Wild Herbs (EWH) Consumption of Local People in Şırnak. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2024, 12, 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemneh, D. Ethnobotany of wild edible plants in Yilmana Densa and Quarit Districts of West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. EthnoBot. Res. Appl. 2020, 20, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakurel, D.; Uprety, Y.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Rajbhandary, S. Foods from the wild: Local knowledge, use pattern and distribution in Western Nepal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitei, L.R.; De, A.; Mao, A.A. An ethnobotanical study on the wild edible plants used by forest dwellers in Yangoupokpi Lokchao Wildlife Sanctuary, Manipur, India. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2022, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzo, S.; Lulekal, E.; Nemomissa, S. Ethnobotanical study of underutilized wild edible plants and threats to their long-term existence in Midakegn District, West Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 115, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, D. Ethnobotanical survey of wild edible plants and their contribution for food security used by Gumuz people in Kamash Woreda; Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 12, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turreira-García, N.; Theilade, I.; Meilby, H.; Sørensen, M. Wild edible plant knowledge, distribution and transmission: A case study of the Achí Mayans of Guatemala. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dous, E.; George, B.; Al-Mahmoud, M.; Al-Jaber, M.; Wang, H.; Salameh, Y.; Al-Azwani, E.K.; Chaluvadi, S.; Pontaroli, A.C.; DeBarry, J.; et al. De novo genome sequencing and comparative genomics of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, R.A.; Al-Mashiqri, J.H.; Al-Nadabi, J.S.M.; Al-Shihi, B.I.; Baqi, Y. Date palm tree (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Nat. Prod. Ther. options. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Guo, C.A.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. An ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants used by the Tibetan in the Rongjia River Valley, Tibet, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqethami, A.; Aldhebiani, A.Y.; Teixidor-Toneu, I. Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A gender perspective. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 257, 112899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqethami, A.; Aldhebiani, A.Y. Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Phytochemical screening. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldhebiani, A.Y.; Alqethami, A.; Alqathama, A.A.; Alarjah, M.; Abdullah, O.A. HPLC and GC-MS Analysis of Five Medicinal Plants Used in Folk Medicine to Treat Respiratory Diseases in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Pioneer. Med. Sci. 2024, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqethami, A. Exploration of Ethnomedicinal Plants and Their Traditional Practices for Therapies During Holy Month of Ramadan İn Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J. Pioneer. Med. Sci. 2024, 13, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboukhalaf, A.; Tbatou, M.; Kalili, A.; Naciri, K.; Moujabbiret, S.; Sahel, K.; Rocha, J.M.; Belahsen, R. Traditional knowledge and use of wild edible plants in Sidi Bennour region (Central Morocco). Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2022, 23, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, I.M.; Amorozo, M.; Neto, G.G.; Oldeland, J.; Damasceno-Junior, G.A. Knowledge and use of wild edible plants in rural com- munities along Paraguay River, Pantanal, Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalmuanpuii, R.; Zodinpuii, B.; Bohia, B.; Zothanpuia Lalbiaknunga, J.; Singh, P.K. Wild edible vegetables of ethnic communities of Mizoram (North east India): An ethnobotanical study in thrust of marketing potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, F.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, M.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, F. Ethnobotanical study of the wild edible and healthy functional plant resources of the Gelao people in northern Guizhou, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Reyes-García, V.; Tardío, J.; Salpeteur, M.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. The importance of cultural factors in the distribution of medicinal plant knowledge: A case study in four Basque regions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 161, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, A. Diversity and potential contribution of wild edible plants to sustainable food security in North Wollo, Ethiopia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22, 2501–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.M.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, N.; Shah, M.H. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinally important wild edible fruits species used by tribal communities of Lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, G.; Urga, K.; Dikasso, D. Ethnobotanical study of edible wild plants in some selected districts of Ethiopia. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 83–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, Y. Traditionally used wild edible greens in the Aegean Region of Turkey. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. Pol. Tow. Bot. 2012, 81, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahklouf, M. Ethnobotanical study of edible wild plants in Libya. Eur. J. Ecol. 2019, 5, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghad, N.; Ahmed, E.; Belkhiri, A.; Heyden, Y.V.; Demeyer, K. Antioxidant activity of Vitis vinifera, Punica granatum, Citrus aurantium and Opuntia ficus indica fruits cultivated in Algeria. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.G.; Morris, M. Plants of Dhofar, the Southern Region of Oman: Traditional, Economic, and Medicinal Uses; Office of the Adviser for Conservation of the Environment, Diwan of Royal Court, Sultanate of Oman: Muscat, Oman, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tukan, S.K.; Takruri, H.R.; El-Eisawi, D.M. The use of wild edible plants in the Jordanian diet. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 49, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouf, M.; Batal, M.; Moledor, S.; Talhouk, S.N. Exploring the practice of traditional wild plant collection in Lebanon. Food Cult Soc. 2015, 18, 335–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Zahir, H.; Amin, H.I.M.; Sõukand, R. Where tulips and crocuses are popular food snacks: Kurdish traditional foraging reveals traces of mobile pastoralism in Southern Iraqi Kurdistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.H.; Hadjichambi, D.P.; Della, A.; Giusti, M.E.; Pasquale, D.C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Tejero, M.R.G.; Rojas, C.P.S.; Gutierrez, J.R.R.; et al. Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Nut. 2008, 59, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, W.; Mohamoud, E.; Mohamed, O. Portulaca oleracea (Purslane): Nutritive composition and clinicopathological effects on Nubian goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2003, 48, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, G.; Farah, M.H.; Claeson, P.; Hagos, M.; Thulin, M.; Hedberg, O.; Warfa, A.M.; Hassan, A.O.; Elmi, A.H.; Abdurahman, A.D.; et al. Inventory of plants used in traditional medicine in Somalia. IV. Plants of the families Passifloraceae-Zygophyllaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993, 38, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.G.; Morris, M. Ethnoflora of the Socotra Archipelago; Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Urso, V.; Signorini, M.A.; Tonini, M.; Bruschi, P. Wild medicinal and food plants used by communities living in Mopane woodlands of southern Angola: Results of an ethnobotanical field investigation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 177, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišová, E.; Grygorieva, O.; Abrahamová, V.; Schubertova, Z.; Terentjeva, M.; Brindza, J. Characterization of morphological parameters and biological activity of jujube fruit (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.). J. Berry Res. 2017, 7, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maaiden, E.; El Kharrassi, Y.; Moustaid, K.; Essamadi, A.K.; Nasser, B. Comparative study of phytochemical profile between Ziziphus spina christi and Ziziphus lotus from Morocco. J. Food Meas. Charact 2019, 13, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almathkori, R.S.; Alotaibi, R.N.; Alhumaidi, M.S.; Alotibi, S.T.; Althobaiti, S.A.; Farag, S.F. Prevalence of Using Medicinal and Edible Plants During the Covid-19 Pandemic in Taif-Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2023, 12, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aati, H.; El-Gamal, A.; Shaheen, H.; Kayser, O. Traditional use of ethnomedicinal native plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Ray, R.; Sreevidya, E.A. How many wild edible plants do we eat—Their diversity, use, and implications for sustainable food system: An exploratory analysis in India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Number of Informants | Percentage | Number of Plants Listed | Average Number of Plants Listed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 78 | 76% | 151 | 1.94 |

| Male | 24 | 24% | 34 | 1.42 | |

| Age | 20–25 | 19 | 19% | 37 | 1.95 |

| 26–30 | 7 | 7% | 15 | 2.14 | |

| 31–35 | 17 | 17% | 31 | 1.82 | |

| 36–40 | 13 | 13% | 26 | 2 | |

| 41–45 | 11 | 11% | 14 | 1.27 | |

| 46–50 | 12 | 12% | 26 | 2.17 | |

| 51–55 | 7 | 7% | 8 | 1.14 | |

| 56–60 | 11 | 11% | 15 | 1.36 | |

| 61–65 | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1 | |

| 71 and older | 4 | 4% | 12 | 3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 27 | 26% | 53 | 1.96 |

| Married | 68 | 67% | 113 | 1.66 | |

| Widowed | 4 | 4% | 14 | 3.5 | |

| Divorced | 3 | 3% | 5 | 1.67 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 10 | 10% | 23 | 2.3 |

| Primary education | 6 | 6% | 6 | 1 | |

| Secondary education | 26 | 25% | 36 | 1.36 | |

| Undergraduate | 60 | 59% | 117 | 1.95 |

| Scientific Name | Family | Local Name | Part (s) Used | Mode of Preparation | Mode of Utilization | Voucher Specimen | Additional Uses | F | RFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allium baeticum Boiss. | Amaryllidaceae | Korath | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-33 | - | 4 | 0.04 |

| Allium vinicolor Wendelbo | Amaryllidaceae | Basal | Bulbs | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten | EPM-4 | - | 1 | 0.01 |

| Apium graveolens L. | Apiaceae | Korfuss | Stems and leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-37 | - | 4 | 0.04 |

| Avena byzantina K. Koch | Poaceae | Shoofan | Seeds | Dried, ground seeds, and cooked | Eaten as bread | EPM-23 | - | 17 | 0.17 |

| Beta vulgaris L. | Amaranthaceae | Shamandar | Roots | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten as salad and with food | EPM-13 | Medicine; natural dye | 8 | 0.08 |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Cucurbitaceae | Handhal | Seeds | Dried, cooked | Munching | EPM-11 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Cucumis melo L. | Cucurbitaceae | Shammam | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-25 | - | 1 | 0.01 |

| Cuminum cyminum L. | Apiaceae | Kamun | Seeds | Dried, infusion, ground seeds | Eaten with salad and food; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-34 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Cymbopogon schoenanthus (L.) Spreng. | Poaceae | Athkhar | Leaves | Dried, decoction | Eaten with bread and dates; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-1 | Medicine | 3 | 0.03 |

| Eruca vesicaria subsp. sativa (Mill.) | Brassicaceae | Jerjeer | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten as salad | EPM-8 | Medicine | 3 | 0.03 |

| Ficus carica L. | Moraceae | Teen | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-7 | Medicine | 12 | 0.12 |

| Ficus palmata Forssk. | Moraceae | Hamat | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-9 | Medicine | 2 | 0.02 |

| Glebionis coronaria (L.) Tzvelev | Asteraceae | Oghowan | Stems | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-14 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Malvaceae | Karkadah | Flowers | Dried, infusion | Eaten with salad and food; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-27 | Medicine, Natural dye | 2 | 0.02 |

| Hyphaene thebaica (L.) Mart. | Arecaceae | Doom | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten fresh pericarp of the fruit | EPM-40 | Construction, forage, shade, thatch, furniture, brooms and ornamental. | 3 | 0.03 |

| Lactuca serriola L. | Asteraceae | Khas | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten as salad | EPM-38 | - | 1 | 0.01 |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Brassicaceae | Rashad | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten with salad and food | EPM-17 | Medicine | 2 | 0.02 |

| Leptadenia pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne. | Apocynaceae | Markh | Leaves | Dried, cooked | With food | EPM-36 | Medicine, Animal fodder | 3 | 0.03 |

| Malva neglecta Wallr. | Malvaceae | Khoppaizah | Leaves | Dried, cooked | Eaten with food | EPM-12 | - | 2 | 0.02 |

| Matricaria aurea (Loefl.) Sch. Bip. | Asteraceae | Baboonig | Flowers | Dried, infusion | Eaten with salad and food; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-2 | Medicine | 2 | 0.02 |

| Mentha longifolia (L.) L. | Lamiaceae | Habag | Stems and leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked; infusion | Eaten as a salad; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-39 | Medicine | 2 | 0.02 |

| Nigella sativa L. | Ranunculaceae | Habat Albarakah | Seeds | Dried and uncooked | With food | EPM-31 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Lamiaceae | Rehan | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten with salad and food | EPM-18 | Medicine; ornamental | 6 | 0.06 |

| Olea europaea L. | Oleaceae | Zaitoon | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-20 | Medicine | 6 | 0.06 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | Cactaceae | Birshumi | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-3 | - | 2 | 0.02 |

| Origanum syriacum L. | Lamiaceae | Zatar | Leaves | Dried leaves | Eaten with salad and food | EPM-19 | Medicine | 9 | 0.09 |

| Panicum turgidum Forssk. | Poaceae | Dukhn | Seeds | Dried, ground, seeds and cooked | As bread | EPM-41 | Animal fodder; thatch | 16 | 0.16 |

| Phoenix dactylifera L. | Arecaceae | Tamir | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-5 | Construction, forage, shade, thatch, furniture, brooms and ornamental. | 20 | 0.2 |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Portulacaceae | Rejlah | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten as salad and with food | EPM-16 | - | 19 | 0.19 |

| Prunus arabica (Oliv.) Meikle | Rosaceae | Lwz | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-35 | - | 7 | 0.07 |

| Pulicaria incisa (Lam.) DC. | Asteraceae | Shay Aljabl | Stems and leaves | Dried; infusion | Eaten with salad and food; drunk as a hot beverage | EPM-24 | Medicine | 2 | 0.02 |

| Raphanus raphanistrum L. | Brassicaceae | Khardal | Seeds | Dried, ground seeds, and cooked | Eaten with salad and food | EPM-22 | - | 2 | 0.02 |

| Raphanus sativus L. | Brassicaceae | Fijel | Roots | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-30 | - | 1 | 0.01 |

| Rubus sanctus Schreb. | Rosaceae | Toot | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-6 | Medicine; natural dye | 6 | 0.06 |

| Rumex nervosus Vahl | Polygonaceae | Atrah | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-29 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Saccharum spontaneum L. | Poaceae | Qasab | Stems | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw; drunk as juice | EPM-32 | - | 1 | 0.01 |

| Sesamum indicum L. | Pedaliaceae | Sumsum | Seeds | Dried; cooked as oil | With food | EPM-28 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench | Poaceae | Thorah | Seeds | Dried, ground seeds, and cooked | As bread | EPM-15 | Animal fodder | 1 | 0.01 |

| Suaeda maritima (L.) Dumort. | Amaranthaceae | Hamid | Leaves | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten raw | EPM-10 | Medicine | 3 | 0.03 |

| Tamarindus indica L. | Fabaceae | Tamur-hendi | Fruit | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Eaten with food | EPM-26 | Medicine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf. | Rhamnaceae | Seder | Fruits | Fresh, ripe, and uncooked | Fruit eaten | EPM-21 | Medicine | 6 | 0.06 |

| Plant Species | Key Informants (1 to 10) | Sum | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Phoenix dactylifera | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 1st |

| Panicum turgidum | 8 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 86 | 2nd |

| Prunus arabica | 5 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 85 | 3rd |

| Ficus carica | 6 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 81 | 4th |

| Avena byzantine | 9 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 74 | 5th |

| Origanum syriacum | 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 73 | 6th |

| Beta vulgaris | 10 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 67 | 7th |

| Portulaca oleracea | 4 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 56 | 8th |

| Major Threats | Key Informants (1 to 10) | Sum | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Overgrazing | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 47 | 1st |

| Fuel wood collection | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 37 | 2nd |

| The repeated use of multiple species | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 30 | 3rd |

| Urban expansion | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 4th |

| Climate change | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 5th |

| Novel WEPs Makkah (11 Species) | WEPs Used in Other KSA Regions (30 Species) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Allium baeticum | Apium graveolens [52,53] | Lepidium sativum [53] | Raphanus sativus [53] |

| Allium vinicolor | Avena byzantine [53] | Malva neglecta [53] | Rubus sanctus [53] |

| Cuminum cyminum | Beta vulgaris [53] | Matricaria aurea [53] | Rumex nervosus [53] |

| Cymbopogon schoenanthus | Citrullus colocynthis [53] | Mentha longifolia [53] | Sesamum indicum [53] |

| Glebionis coronaria | Cucumis melo [53] | Nigella sativa [53] | Sorghum bicolor [53] |

| Leptadenia pyrotechnica | Eruca vesicaria subsp. sativa [52,53] | Ocimum basilicum [53] | Suaeda maritima [53] |

| Opuntia ficus-indica | Ficus carica [53] | Olea europaea [53,54] | Tamarindus indica [53] |

| Panicum turgidum | Ficus palmata [52,53,54] | Origanum syriacum [53] | Ziziphus spina-christi [51,53] |

| Prunus arabica | Hibiscus sabdariffa [53] | Phoenix dactylifera [51,53] | |

| Raphanus raphanistrum | Hyphaene thebaica [51,53,54] | Portulaca oleracea [53] | |

| Saccharum spontaneum | Lactuca serriola [53] | Pulicaria incisa [53] | |

| Same WEP Used in Neighboring Countries (Yemen and Oman) | Same WEP Used in Other Asian and African Countries |

|---|---|

| Ficus palmata Yeman [56] | Ficus palmata Pakistan [102]; Ethiopia [103] |

| Lactuca serriola Yeman [56] | Lactuca serriola L. Turkey [104]; Libya [105] |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Yeman [56] | Opuntia ficus-indica Algeria [106]; Ethiopia [103]; Libya [105] |

| Portulaca oleracea Yeman [56]; Oman [107] | Portulaca oleracea Jordan [108]; Palestine [74]; Lebanon [109]; Iraq [110]; Turkey [104]; Egypt [111]; Libya [105]; Morocco [111]; Sudan [112]; Somalia [113] |

| Rumex nervosus Yeman [56] | Ziziphus spina-christi Soqotra [114]; Angola [115]; Ethiopia [7]; Libya [105]; Egypt [111]; Sudan [77]; Palestine [74]; Tunisia [116]; Morocco [117] |

| Ziziphus spina-christi Yeman [56]; Oman [107] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqethami, A. Ethnobotanical Assessment of the Diversity of Wild Edible Plants and Potential Contribution to Enhance Sustainable Food Security in Makkah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Diversity 2025, 17, 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110785

Alqethami A. Ethnobotanical Assessment of the Diversity of Wild Edible Plants and Potential Contribution to Enhance Sustainable Food Security in Makkah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Diversity. 2025; 17(11):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110785

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqethami, Afnan. 2025. "Ethnobotanical Assessment of the Diversity of Wild Edible Plants and Potential Contribution to Enhance Sustainable Food Security in Makkah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" Diversity 17, no. 11: 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110785

APA StyleAlqethami, A. (2025). Ethnobotanical Assessment of the Diversity of Wild Edible Plants and Potential Contribution to Enhance Sustainable Food Security in Makkah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Diversity, 17(11), 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110785