Scale-Dependent Drivers of Plant Community Turnover in a Disturbed Grassland: Insights from Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

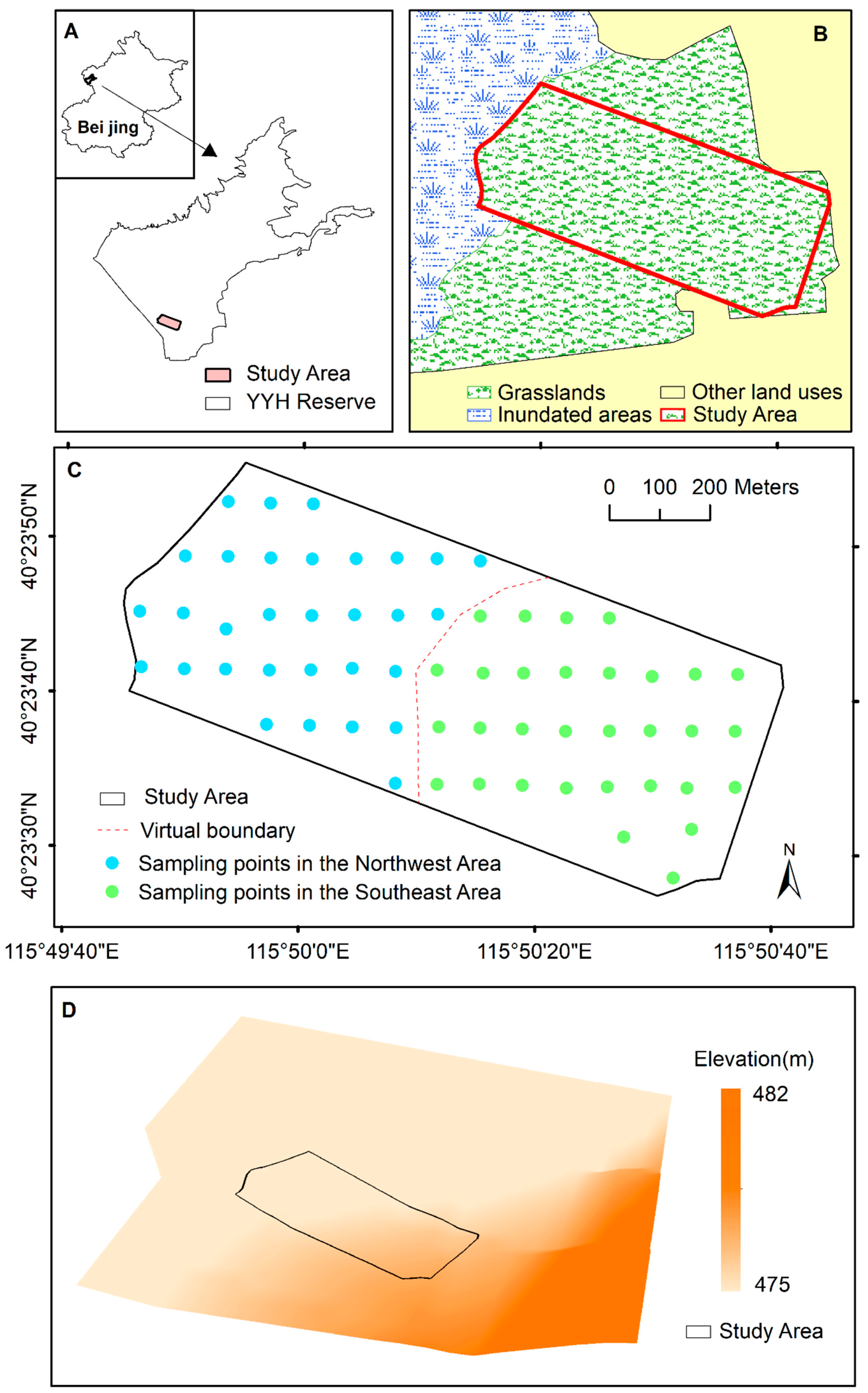

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey and Analysis of Plant Community and Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.3. Remote Sensing Data

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Modeling

2.4.1. Species Importance Value and Ecological Types

2.4.2. GDM and Evaluation

2.4.3. Variable Selection Process

3. Results

3.1. Plant Community Composition and Distribution in the Three Areas

3.2. Comparison of Soil Properties Between the Two Subareas

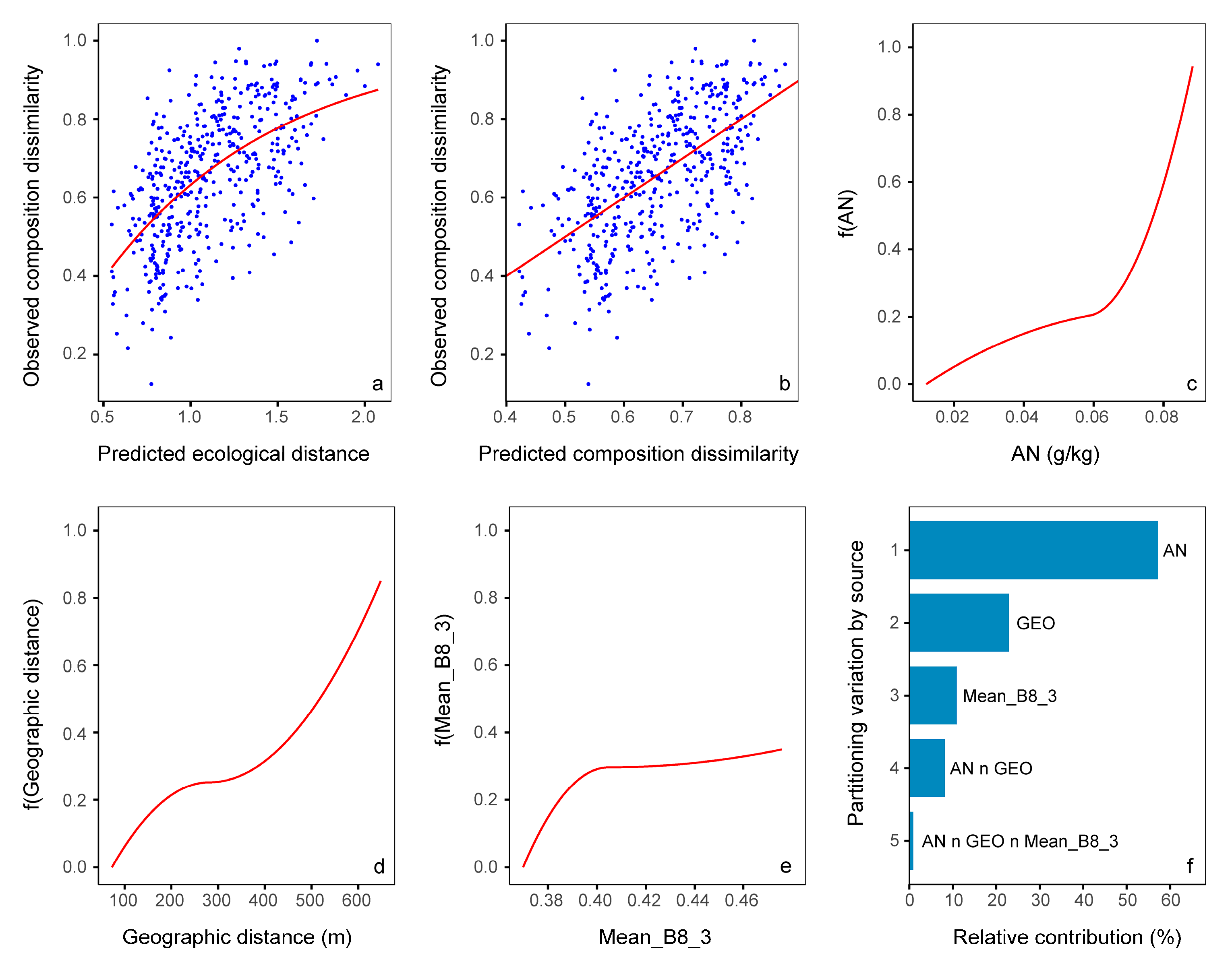

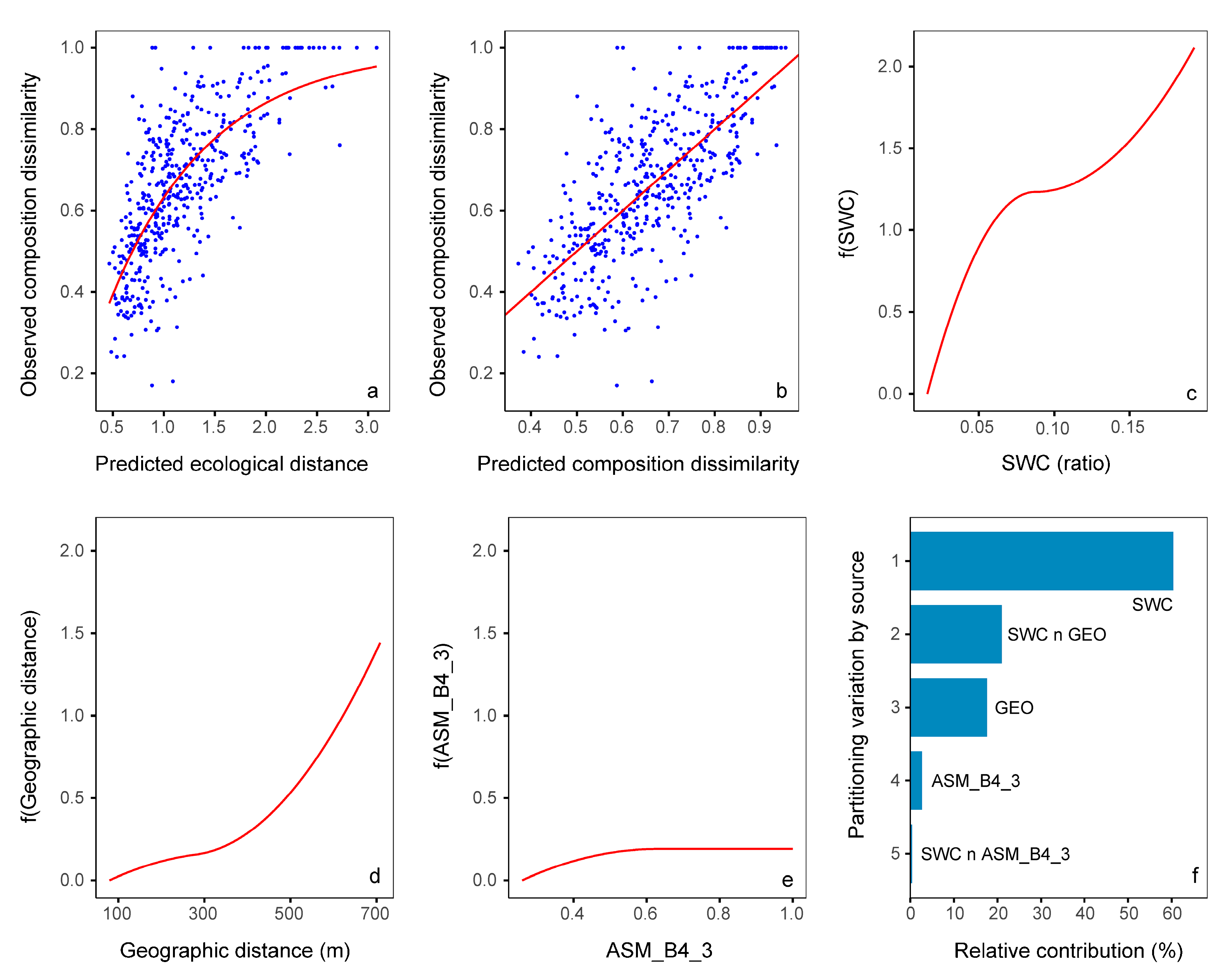

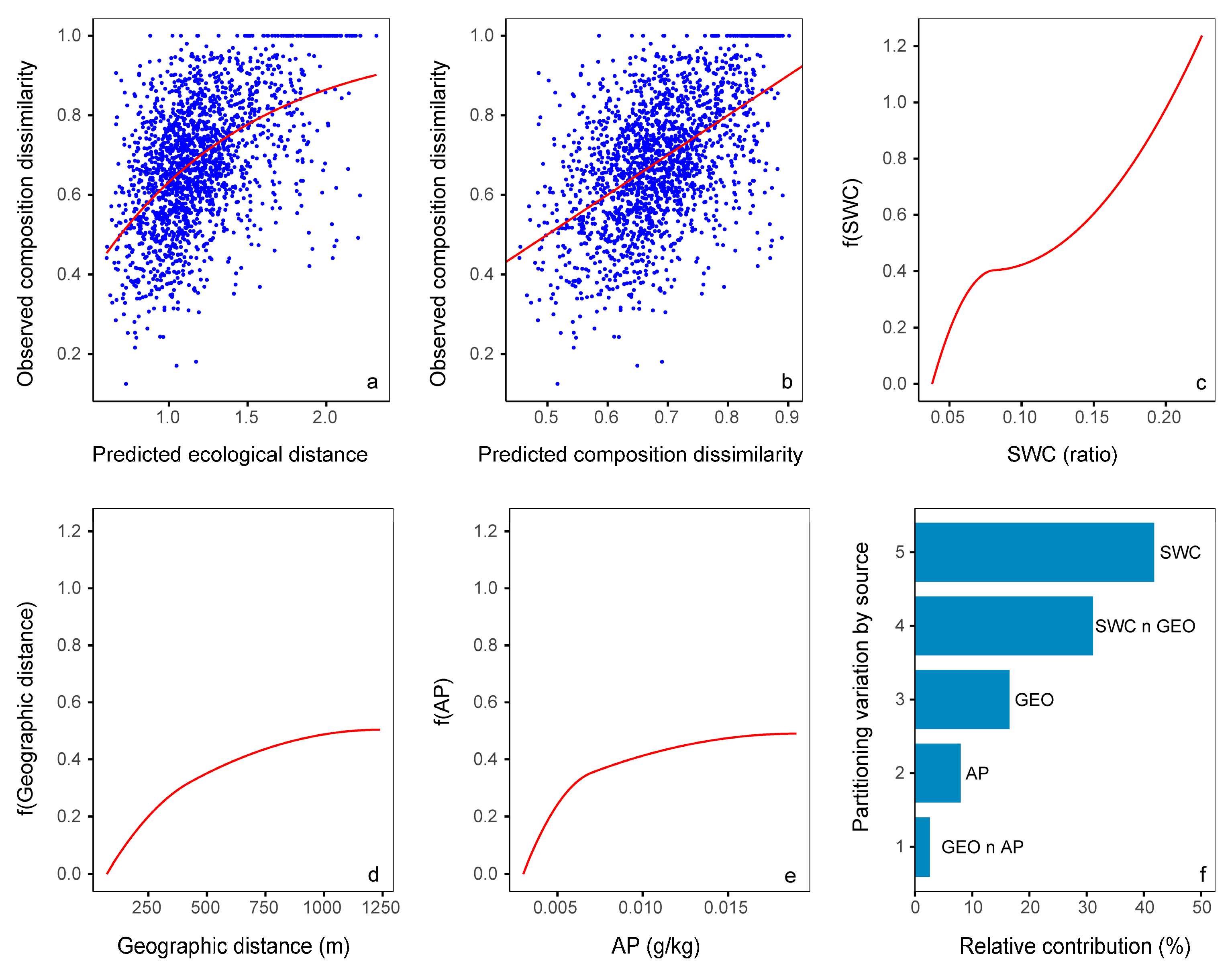

3.3. Model Evaluation

3.4. Patterns of Species Turnover

3.5. Relative Importance of Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Soil Properties on Plant Community Composition and Distribution

4.2. Relationship Between the Proportion of Deviance Explained by GDM and Explanatory Variables

4.3. Similar Patterns Arise from Different Driving Mechanisms

4.4. The Role of Geographic Distance at Different Spatial Scales

4.5. The Role of Remote Sensing Variables

4.6. Effects of Disturbance on Monitoring

4.7. Scale Dependence of the GDM Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Vegetation Index | Abbreviation | Formulation | Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity Index_S1 | S1 | Blue/Red | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_S2 | S2 | (Blue − Red)/(Blue + Red) | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_S3 | S3 | (Green × Red)/Blue | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_S5 | S5 | (Blue × Red)/Green | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_S601 | S601 | (Red × NIR1)/Green | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_S602 | S602 | (Red × NIR2)/Green | A | [75] |

| Salinity Index_1 | Sal1 | (Green × Red)1/2 | A | [76] |

| Salinity Index_201 | Sal201 | (Green2)1/2 + Red2 + NIR12 | A | [77] |

| Salinity Index_202 | Sal202 | (Green2)1/2 + Red2 + NIR22 | A | [77] |

| Salinity Index_3 | Sal3 | (Green2 + Red2)1/2 | A | [77] |

| Salinity Index_SI-T01 | SI-T01 | Red/NIR1 × 100 | A | [78] |

| Salinity Index-SI-T02 | SI-T01 | Red/NIR2 × 100 | A | [78] |

| Brightness Index_BI01 | BI01 | (NIR12 + Red2)1/2 | A | [76] |

| Brightness Index-BI02 | BI02 | (NIR22 + Red2)1/2 | A | [76] |

| Triangular Vegetation Index | TVI653 | 0.5 × (120 × (Red Edge − Green) − 200 × (Red − Green)) | B | [79] |

| Structure-Insensitive Pigment Index | SIPI | (NIR1 − Blue)/(NIR1 − Red Edge) | B | [80] |

| RedEdge Simple Ratio Index | RE-SR 65 | Red Edge/Red | B | [81] |

| Pigment-Specific Simple Ratio (Chlorophyll a) | PSSRa | NIR1/Red Edge | B | [82] |

| Pigment-Specific Simple Ratio (Chlorophyll b) | PSSRb | NIR1/Red | B | [82] |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Index | CRI | (1/Blue) − (1/Red Edge) | B | [83] |

| Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | TCARI753 | 3 × [(NIR1 − Red) − 0.2 × (NIR1 − Green) × (NIR1/Red)] | B | [84] |

| Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | TCARI | 3 × [(Red Edge − Red) − 0.2 × (Red Edge − Green)(Red Edge/Red)] | B | [79] |

| Modified Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | MCARI | [(Red Edge − Red) − 0.2 × (Red Edge − Green)] × (Red Edge/Red) | B | [85] |

| Modified Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | MCARI753 | [(NIR1 − Red) − 0.2(NIR1 − Green)] × (NIR1/Red) | B | [84] |

| Plant Senescence Reflectance Index | PSRI | (Red Edge − Blue)/NIR1 | B | [86] |

| RedEdge Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | RE-NDVI65 | (Red Edge − Red)/(Red Edge + Red) | B | [81] |

| Modified RedEdge Simple Ratio Index | mRE-SR651 | (Red Edge − Coastal Blue)/(Red + Coastal Blue) | B | [81] |

| Simple Ratio Index_85 | SRI85 | NRI2/Red | C | [81] |

| Simple Ratio Index | SRI | NRI1/Red | C | [87] |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | SRI84 | NRI2/Yellow | C | [81] |

| RedEdge Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | RE-NDVI61 | (Red Edge − Coastal Blue)/(Red Edge + Coastal Blue) | C | [81] |

| RedEdge Simple Ratio Index | RE-SR61 | Red Edge/Coastal Blue | C | [79] |

| Ratio Vegetation Index | RVI01 | Red/NIR1 | C | [88] |

| Ratio Vegetation Index | RVI02 | NIR1/Red | C | [89] |

| Transformed Vegetation Index | TVI | (NDVI + 0.5)1/2 | C | [90] |

| Normalized Difference Index | NDI | (NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + Red) | C | [91] |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | GNDVI | (NIR1 − Green)/(NIR1 + Green) | C | [89,92,93] |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index 2 | GNDVI2 | (NIR2 − Green)/(NIR2 + Green) | C | [94] |

| Modified Simple Ratio | MSR75 | [(NIR1/Red) − 1]/[(NIR1/Red)1/2 + 1] | C | [84] |

| Modified Simple Ratio | MSR02 | (NIR1 − Blue)/(Red − Blue) | C | [91] |

| Visible Green Index | VGI | (Green − Red)/(Green + Red) | C | [95] |

| Modified Normalized Difference | MND | (NIR1 − Blue)/(NIR1 + Red Edge − 2 × Blue) | C | [91] |

| Green Index | GI | (NIR1/Green) − 1 | C | [83] |

| Red Index | RI | (NIR1/Red) − 1 | C | [83] |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge index | NDRE | (NIR1 − Red Edge)/(NIR1 + Red Edge) | C | [96] |

| Renormalized Vegetation Index | RDVI | (NIR1 − red)/(NIR1 + red)1/2 | C | [89] |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | NDVI | (NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + Red) | C | [97] |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge index 2 | NDRE2 | (NIR2 − Red Edge)/(NIR2 + Red Edge) | C | [94] |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index 2 | NDVI202 | (NIR2 − red)/(NIR2 + red) | C | [97] |

| NDVI 3 | (NIR1−Yellow)/(NIR1 + Yellow) | C | [98] | |

| NDVI 4 | (Red Edge − Coastal Blue)/(Red Edge + Coastal Blue) | C | [98] | |

| NDVI 5 | (Red Edge − Red)/(Red Edge + Red) | C | [98] | |

| NDVI 6 | (NIR2 − Yellow)/(NIR2 + Yellow) | C | [81] | |

| Generalized Difference VI | GDVI | (NIR12 − Red2)/(NIR12 + Red2) | C | [99] |

| Detection index | DI | NIR2/Red Edge | C | [100] |

| Normalized Difference Water Index01 | NDWI01 | (NIR1 − NIR2)/(NIR1 + NIR2) | C | [81,101,102] |

| Normalized Difference Water Index02 | NDWI02 | (Green − NIR2)/(Green + NIR2) | C | [103] |

| Optimized Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | OSAVI75 | (1 + 0.6)(NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + Red + 0.16) | D | [79] |

| Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | MSAVI | (1 + 0.5)(NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + Red + 0.5) | D | [104] |

| Soil-Adjusted VI01 | Savi01 | 1.5 × (NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + Red + 0.5) | D | [105] |

| Soil-Adjusted VI02 | Savi02 | 1.5 × (NIR2 − Red)/(NIR2 + Red + 0.5) | D | [105] |

| Soil–Adjusted VI 201 | Savi201 | 1.5 × (NIR1 − Yellow)/(NIR1 + Yellow + 0.5) | D | [105] |

| Soil-Adjusted VI 202 | Savi202 | 1.5 × (NIR2 − Yellow)/(NIR2 + Yellow + 0.5) | D | [105] |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | EVI | 2.5 × ((NIR1 − Red)/(NIR1 + 6 × Red − 7.5 × Blue + 1)) | D | [106] |

| Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index | ARVI | (NIR2 − (2 × Red − Blue))/(NIR2 + (2 × Red − Blue)) | D | [107] |

| Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index | VARI | (Green − Red)/(Green + Red − Blue) | D | [95] |

| Scientific Name | IV | Ecological Type |

|---|---|---|

| Artemisia tanacetifolia L. | 12.17 | Mesophytic |

| Artemisia lavandulaefolia DC. | 8.66 | Mesophytic |

| Gueldenstaedtia verna (Georgi) Boriss. | 7.34 | Mesophytic |

| Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Keng | 6.77 | Mesophytic |

| Hemarthria altissima (Poir.) Stapf et C. E. Hubb. | 6.35 | Hydrophytic |

| Scirpus planiculmis Fr.schmibt | 6.01 | Emergent |

| Lespedeza davurica (Laxm.) Schindl. | 4.84 | Mesophytic |

| Plantago asiatica L. | 4.52 | Mesophytic |

| Taraxacum brassicaefolium Kitag. | 3.03 | Mesophytic |

| Echinochloa crusgalli (L.) Beauv. | 2.88 | Mesophytic |

| Inula japonica Thunb. | 2.41 | Mesophytic |

| Plantago depressa Willd. | 2.36 | Mesophytic |

| Sphaerophysa salsula (Pall.) DC. | 2.20 | Halophytic |

| Chloris virgata Sw. | 2.09 | Mesophytic |

| Elymus dahuricus Turcz. | 1.99 | Halophytic |

| Sonchus wightianus DC. | 1.98 | Hydrophytic |

| Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. | 1.97 | Mesophytic |

| Tournefortia sibirica L. | 1.97 | Mesophytic |

| Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | 1.92 | Emergent |

| Ixeris chinensis (Thunb.) Nakai | 1.81 | Mesophytic |

| Species Name | IV | Ecological Type |

|---|---|---|

| Hemarthria altissima (Poir.) Stapf et C. E. Hubb. | 19.92 | Hydrophytic |

| Scirpus planiculmis Fr.schmibt | 14.21 | Emergent |

| Artemisia tanacetifolia L. | 10.76 | Mesophytic |

| Inula japonica Thunb. | 7.22 | Mesophytic |

| Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. | 5.07 | Mesophytic |

| Potentilla anserina L. | 4.56 | Halophytic |

| Artemisia lavandulaefolia DC. | 4.50 | Mesophytic |

| Echinochloa crusgalli (L.) Beauv. | 3.50 | Mesophytic |

| Plantago depressa Willd. | 3.12 | Mesophytic |

| Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | 2.54 | Emergent |

| Typha angusitifolia L. | 2.23 | Emergent |

| Plantago major L. | 1.94 | Mesophytic |

| Typha davidiana (Kronf.) Hand. -Mazz | 1.81 | Emergent |

| Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Keng | 1.69 | Mesophytic |

| Elymus dahuricus Turcz. | 1.63 | Halophytic |

| Plantago asiatica L. | 1.54 | Mesophytic |

| Potentilla chinensis Ser. | 1.03 | Mesophytic |

| Equisetum palustre L. | 0.96 | Hydrophytic |

| Xanthium strumarium L. | 0.96 | Mesophytic |

| Lespedeza davurica (Laxm.) Schindl. | 0.89 | Mesophytic |

| Scientific Name | IV | Ecological Type |

| Scirpus planiculmis Fr.schmibt | 14.99 | Emergent |

| Hemarthria altissima (Poir.) Stapf et C. E. Hubb. | 14.19 | Hydrophytic |

| Artemisia tanacetifolia L. | 12.03 | Mesophytic |

| Artemisia lavandulaefolia DC. | 5.95 | Mesophytic |

| Inula japonica Thunb. | 4.28 | Mesophytic |

| Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Keng | 4.25 | Mesophytic |

| Apocynum venetum L. | 3.33 | Halophytic |

| Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. | 3.22 | Mesophytic |

| Echinochloa crusgalli (L.) Beauv. | 2.96 | Mesophytic |

| Plantago asiatica L. | 2.93 | Mesophytic |

| Gueldenstaedtia verna (Georgi) Boriss. | 2.86 | Mesophytic |

| Potentilla anserina L. | 2.83 | Halophytic |

| Plantago depressa Willd. | 2.52 | Mesophytic |

| Lespedeza davurica (Laxm.) Schindl. | 2.05 | Mesophytic |

| Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | 1.89 | Emergent |

| Elymus dahuricus Turcz. | 1.82 | Halophytic |

| Taraxacum brassicaefolium Kitag. | 1.35 | Mesophytic |

| Chloris virgata Sw. | 1.14 | Mesophytic |

| Typha angusitifolia L. | 1.06 | Emergent |

| Plantago major L. | 1.04 | Mesophytic |

References

- Legendre, P.; De Cáceres, M. Beta Diversity as the Variance of Community Data: Dissimilarity Coefficients and Partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. Evolution and Measurement of Species Diversity. TAXON 1972, 21, 213–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.L. Species Diversity in Space and Time; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; ISBN 978-0-511-62338-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cody, M.L. Towards a Theory of Continental Species Diversities: Bird Distributions Over Mediterranean Habitat Gradients. In Ecology and Evolution of Communities; Cody, M.L., Diamond, J.M., Eds.; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 214–257. ISBN 978-0-674-22444-5. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E.; McGill, B.J. Biological Diversity: Frontiers in Measurement and Assessment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-958066-8. [Google Scholar]

- Si, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, C.; Ren, P.; Zeng, D.; Wu, L.; Ding, P. Beta-diversity partitioning: Methods, applications and perspectives. Biodivers. Sci. 2017, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. The Relationship between Species Replacement, Dissimilarity Derived from Nestedness, and Nestedness. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.M.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Jandt, U.; Chytrý, M.; Field, R.; Kessler, M.; Lenoir, J.; Schrodt, F.; Wiser, S.K.; Arfin Khan, M.A.S.; et al. Global Patterns of Vascular Plant Alpha Diversity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Večeřa, M.; Divíšek, J.; Lenoir, J.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Biurrun, I.; Knollová, I.; Agrillo, E.; Campos, J.A.; Čarni, A.; Crespo Jiménez, G.; et al. Alpha Diversity of Vascular Plants in European Forests. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 1919–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmayne, J.; Möckel, T.; Prentice, H.C.; Schmid, B.C.; Hall, K. Assessment of Fine-Scale Plant Species Beta Diversity Using WorldView-2 Satellite Spectral Dissimilarity. Ecol. Inform. 2013, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Somerfield, P.J.; Chapman, M.G. On Resemblance Measures for Ecological Studies, Including Taxonomic Dissimilarities and a Zero-Adjusted Bray–Curtis Coefficient for Denuded Assemblages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 330, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokany, K.; Ware, C.; Woolley, S.N.C.; Ferrier, S.; Fitzpatrick, M.C. A Working Guide to Harnessing Generalized Dissimilarity Modelling for Biodiversity Analysis and Conservation Assessment. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, M.W.; White, P.S.; McDonald, R.I.; Lamoreux, J.F.; Sechrest, W.; Ridgely, R.S.; Stuart, S.N. Putting Beta-Diversity on the Map: Broad-Scale Congruence and Coincidence in the Extremes. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socolar, J.B.; Gilroy, J.J.; Kunin, W.E.; Edwards, D.P. How Should Beta-Diversity Inform Biodiversity Conservation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossner, M.M.; Lewinsohn, T.M.; Kahl, T.; Grassein, F.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Birkhofer, K.; Renner, S.C.; Sikorski, J.; Wubet, T.; et al. Land-Use Intensification Causes Multitrophic Homogenization of Grassland Communities. Nature 2016, 540, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Lin, S.; Kong, F.; Yu, J.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, H. Determinants of the Beta Diversity of Tree Species in Tropical Forests: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekola, J.C.; White, P.S. The Distance Decay of Similarity in Biogeography and Ecology. J. Biogeogr. 1999, 26, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Devasa, R.; Martínez-Santalla, S.; Gómez-Rodríguez, C.; Crujeiras, R.M.; Baselga, A. Species Range Size Shapes Distance-decay in Community Similarity. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, E.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; García-Oliva, F.; Oyama, K. Influence of Environmental Heterogeneity and Geographic Distance on Beta-Diversity of Woody Communities. Plant Ecol. 2020, 221, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Ricklefs, R.E. Disentangling the Effects of Geographic Distance and Environmental Dissimilarity on Global Patterns of Species Turnover. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, V.S.; Soininen, J.; Fonseca-Gessner, A.A.; Siqueira, T. Dispersal Traits Drive the Phylogenetic Distance Decay of Similarity in Neotropical Stream Metacommunities. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 2101–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, C.; Weigelt, P.; Kreft, H. Dissecting Global Turnover in Vascular Plants. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. Beta Diversity in Relation to Dispersal Ability for Vascular Plants in North America. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.W. Distance Decay in an Old-growth Neotropical Forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2005, 16, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Sorte, F.A.; McKinney, M.L.; Pyšek, P.; Klotz, S.; Rapson, G.L.; Celesti-Grapow, L.; Thompson, K. Distance Decay of Similarity among European Urban Floras: The Impact of Anthropogenic Activities on β Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008, 17, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, M.J.; Dolos, K.; Reineking, B.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Current Measures for Distance Decay in Similarity of Species Composition Are Influenced by Study Extent and Grain Size. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; Cardoso, P.; Gomes, P. Determining the Relative Roles of Species Replacement and Species Richness Differences in Generating Beta-diversity Patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Disentangling Distance Decay of Similarity from Richness Gradients: Response to Soininen et al. 2007. Ecography 2007, 30, 838–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, G.; Ferrín, M.; Sardans, J.; Verbruggen, E.; Ramírez-Rojas, I.; Van Langenhove, L.; Verryckt, L.T.; Murienne, J.; Iribar, A.; Zinger, L.; et al. Decay of Similarity across Tropical Forest Communities: Integrating Spatial Distance with Soil Nutrients. Ecology 2022, 103, e03599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graco-Roza, C.; Aarnio, S.; Abrego, N.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Alahuhta, J.; Altman, J.; Angiolini, C.; Aroviita, J.; Attorre, F.; Baastrup-Spohr, L.; et al. Distance Decay 2.0—A Global Synthesis of Taxonomic and Functional Turnover in Ecological Communities. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 1399–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D. Distance Decay in Spectral Space in Analysing Ecosystem Β-diversity. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 2635–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shin, Y.H. Spatial Autocorrelation Potentially Indicates the Degree of Changes in the Predictive Power of Environmental Factors for Plant Diversity. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Cade, B.S. Quantile Regression Applied to Spectral Distance Decay. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.; Poulsen, A.D.; Ruokolainen, K.; Moran, R.C.; Quintana, C.; Celi, J.; Cañas, G. Linking Floristic Patterns with Soil Heterogeneity and Satellite Imagery in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Ecol. Appl. 2003, 13, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Proença, V.; Serra, P.; Palma, J.; Domingo-Marimon, C.; Pons, X.; Domingos, T. Remotely Sensed Indicators and Open-Access Biodiversity Data to Assess Bird Diversity Patterns in Mediterranean Rural Landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Deng, Y.; Lü, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Han, X. Scale-Dependent Effects of Climate and Geographic Distance on Bacterial Diversity Patterns across Northern China’s Grasslands. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, fiv133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Shimono, A. Effects of Geographic Distance and Climatic Dissimilarity on Species Turnover in Alpine Meadow Communities across a Broad Spatial Extent on the Tibetan Plateau. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Tripathi, B.M.; Shi, Y.; Adams, J.M.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, H. Interpreting Distance-decay Pattern of Soil Bacteria via Quantifying the Assembly Processes at Multiple Spatial Scales. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e00851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Ricklefs, R.E.; White, P.S. Beta Diversity of Angiosperms in Temperate Floras of Eastern Asia and Eastern North America. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L.B.; Jetz, W. Linking Global Turnover of Species and Environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17836–17841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Sanders, N.J.; Normand, S.; Svenning, J.-C.; Ferrier, S.; Gove, A.D.; Dunn, R.R. Environmental and Historical Imprints on Beta Diversity: Insights from Variation in Rates of Species Turnover along Gradients. Proc. R. Soc. B 2013, 280, 20131201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, S.; Manion, G.; Elith, J.; Richardson, K. Using Generalized Dissimilarity Modelling to Analyse and Predict Patterns of Beta Diversity in Regional Biodiversity Assessment. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, S.; Powell, G.V.N.; Richardson, K.S.; Manion, G.; Overton, J.M.; Allnutt, T.F.; Cameron, S.E.; Mantle, K.; Burgess, N.D.; Faith, D.P.; et al. Mapping More of Terrestrial Biodiversity for Global Conservation Assessment. BioScience 2004, 54, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Tonteri, T. Rate of Compositional Turnover along Gradients and Total Gradient Length. J. Veg. Sci. 1995, 6, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, S. Mapping Spatial Pattern in Biodiversity for Regional Conservation Planning: Where to from Here? Syst. Biol. 2002, 51, 331–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Mokany, K.; Manion, G.; Nieto-Lugilde, D.; Ferrier, S. gdm: Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling. Reference Manual. R Package Version 1.6.0-7. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gdm/gdm.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Lasram, F.B.R.; Hattab, T.; Halouani, G.; Romdhane, M.S.; Le Loc’h, F. Modeling of Beta Diversity in Tunisian Waters: Predictions Using Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling and Bioregionalisation Using Fuzzy Clustering. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Sanders, N.J.; Ferrier, S.; Longino, J.T.; Weiser, M.D.; Dunn, R. Forecasting the Future of Biodiversity: A Test of Single- and Multi-Species Models for Ants in North America. Ecography 2011, 34, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.; Catullo, R.; Mokany, K.; Harwood, T.; Hoskins, A.J.; Ferrier, S. Incorporating Existing Thermal Tolerance into Projections of Compositional Turnover under Climate Change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, W.; Guo, X.; Hu, D.; Gong, Z.; Long, J. Spectral Bands of Typical Wetland Vegetation in the W Ild Duck Lake. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 5853–5861. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, W.; Hu, D. Wetland Plant Community Characteristics and Ecological Succession Mode in Wild Duck Lake along Salt and Water Environment Gradient. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Responses and Indicators of Composition, Diversity, and Productivity of Plant Communities at Different Levels of Disturbance in a Wetland Ecosystem. Diversity 2021, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000; ISBN 978-7-109-06644-1. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X. Soil and Plant Nutrition Experiment, 1st ed.; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2014; ISBN 7-308-13552-7. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Dai, J.; Feng, H.; Lu, Y.; Jia, C.; Chen, C.; Xiong, F. Standard mapping of soil textural triangle and automatic query of soil texture classes. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2013, 50, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.J. Vegetation Index Suites as Indicators of Vegetation State in Grassland and Savanna: An Analysis with Simulated SENTINEL 2 Data for a North American Transect. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 137, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.; Chen, J.; Lu, N.; Guo, K.; Liang, C.; Wei, Y.; Noormets, A.; Ma, K.; Han, X. Predicting Plant Diversity Based on Remote Sensing Products in the Semi-Arid Region of Inner Mongolia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2018–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fu, G. Quantifying Plant Species α-Diversity Using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Climate Data in Alpine Grasslands. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, Z.; Tang, Z.; He, J.; Yu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, J.; et al. Methods and protocols for plant community inventory. Biodivers. Sci. 2009, 17, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Gong, H.; Hu, D. Wetland Plants in Wild Duke Lake, Beijing, 1st ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012; ISBN 978-7-5111-0953-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with It and a Simulation Study Evaluating Their Performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, L.; Lin, Q. Wetland Plants in Beijing, 1st ed.; Beijing Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2009; ISBN 978-7-5304-4532-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q. Large-Scale Geographic Patterns and Environmental and Anthropogenic Drivers of Wetland Plant Diversity in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. BMC Ecol. Evo 2024, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, H.W.; Yang, C.; Wilsey, B.J.; Fay, P.A. Spectral Heterogeneity Predicts Local-Scale Gamma and Beta Diversity of Mesic Grasslands. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, T.; Keppel, G.; Baider, C.; Birkinshaw, C.; Culmsee, H.; Cordell, S.; Florens, F.B.V.; Franklin, J.; Giardina, C.P.; Gillespie, T.W.; et al. Regional Forcing Explains Local Species Diversity and Turnover on Tropical Islands. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Schneider, F.D.; Santos, M.J.; Armstrong, A.; Carnaval, A.; Dahlin, K.M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hurtt, G.C.; Schimel, D.; Townsend, P.A.; et al. Integrating Remote Sensing with Ecology and Evolution to Advance Biodiversity Conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Nagendra, H.; Rocchini, D.; Rowcliffe, M.; Williams, R.; Ahumada, J.; De Angelo, C.; Atzberger, C.; Boyd, D.; Buchanan, G.; et al. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation: Three Years On. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 3, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, A.M.; Foody, G.M.; Boyd, D.S. Applications in Remote Sensing to Forest Ecology and Management. One Earth 2020, 2, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, J. Review of Remote Sensing Applications in Grassland Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Suárez-Seoane, S.; Chytrý, M.; Hennekens, S.M.; Willner, W.; Hájek, M.; Agrillo, E.; Álvarez-Martínez, J.M.; Bergamini, A.; Brisse, H.; et al. Modelling the Distribution and Compositional Variation of Plant Communities at the Continental Scale. Divers. Distrib. 2018, 24, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kühn, I.; Kunin, W.E.; Kuussaari, M.; Settele, J.; Henle, K.; Brotons, L.; Pe’er, G.; Lengyel, S.; et al. Patterns of Beta Diversity in Europe: The Role of Climate, Land Cover and Distance across Scales. J. Biogeogr. 2012, 39, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C.; Coops, N.C.; Butson, C.R. Multi-Temporal Analysis of High Spatial Resolution Imagery for Disturbance Monitoring. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2729–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckenberg, T.; Münch, Z.; van Niekerk, A. Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Land-Cover Change Detection for Biodiversity Assessment in the Berg River Catchment. South Afr. J. Geomat. 2013, 2, 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.; Khan, S. Using Remote Sensing Techniques for Appraisal of Irrigated Soil Salinity. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Modelling and Simulation. (MODSIM 2007), Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand, Christchurch, New Zealand, 10–13 December 2007; pp. 2632–2638. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Shalina, E.V.; Sato, Y. Mapping Salt-Affected Soils Using Remote Sensing Indicators—A Simple Approach with the Use of GIS IDRISI. In Proceedings of the 22nd Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Singapore, 5 November 2001; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Douaoui, A.E.K.; Nicolas, H.; Walter, C. Detecting Salinity Hazards within a Semiarid Context by Means of Combining Soil and Remote-Sensing Data. Geoderma 2006, 134, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.K.; Rai, B.K.; Dwivedi, P. Spatial Modelling of Soil Alkalinity in GIS Environment Using IRS Data. In Proceedings of the 18th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 20–25 October 1997; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Tremblay, N.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Dextraze, L. Integrated Narrow-Band Vegetation Indices for Prediction of Crop Chlorophyll Content for Application to Precision Agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluelas, J.; Baret, F.; Filella, I. Semi-Empirical Indices to Assess Carotenoids/Chlorophyll a Ratio from Leaf Spectral Reflectance. Photosynthetica 1995, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, R.; Landry, S. A Comparative Analysis of High Spatial Resolution IKONOS and WorldView-2 Imagery for Mapping Urban Tree Species. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 124, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, G.A. Spectral Indices for Estimating Photosynthetic Pigment Concentrations: A Test Using Senescent Tree Leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote Estimation of Canopy Chlorophyll Content in Crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, 2005GL022688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Barragán, J.M.; Ngugi, M.K.; Plant, R.E.; Six, J. Object-Based Crop Identification Using Multiple Vegetation Indices, Textural Features and Crop Phenology. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1301–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtry, C. Estimating Corn Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration from Leaf and Canopy Reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Rakitin, V.Y. Non-destructive Optical Detection of Pigment Changes during Leaf Senescence and Fruit Ripening. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 106, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of Leaf-Area Index from Quality of Light on the Forest Floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J.; Weigand, C. Distinguishing Vegetation from Soil Background Information. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1977, 43, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Luo, J.; Jin, X.; Xu, X.; Song, X.; Yang, G. Exploring the Best Hyperspectral Features for LAI Estimation Using Partial Least Squares Regression. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 6221–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, D.; Rouse, J. Measuring “Forage Production” of Grazing Units from Landsat MSS Data. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 6–10 October 1975; pp. 1169–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between Leaf Pigment Content and Spectral Reflectance across a Wide Range of Species, Leaf Structures and Developmental Stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, T.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ting, K.C. A Review of Remote Sensing Methods for Biomass Feedstock Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2455–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Adam, E.; Cho, M.A. High Density Biomass Estimation for Wetland Vegetation Using WorldView-2 Imagery and Random Forest Regression Algorithm. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 18, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel Algorithms for Remote Estimation of Vegetation Fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.M.; Clarke, T.R.; Richards, S.E.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T. Coincident Detection of Crop Water Stress, Nitrogen Status and Canopy Density Using Ground-Based Multispectral Data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abood, S.; Maclean, A.; Falkowski, M. Soil Salinity Detection in the Mesopotamian Agricultural Plain Utilizing WorldView-2 Imagery; Michigan Technological University: Houghton, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, H.; Beecham, S.; Anderson, S.; Nagler, P. High Spatial Resolution WorldView-2 Imagery for Mapping NDVI and Its Relationship to Temporal Urban Landscape Evapotranspiration Factors. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 580–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Mhaimeed, A.S.; Al-Shafie, W.M.; Ziadat, F.; Dhehibi, B.; Nangia, V.; De Pauw, E. Mapping Soil Salinity Changes Using Remote Sensing in Central Iraq. Geoderma Reg. 2014, 2–3, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, D.D.; Daliakopoulos, I.N.; Panagea, I.S.; Tsanis, I.K. Assessing Soil Salinity Using WorldView-2 Multispectral Images in Timpaki, Crete, Greece. Geocarto Int. 2018, 33, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. NDWI—A Normalized Difference Water Index for Remote Sensing of Vegetation Liquid Water from Space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartling, S.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Carron, J. Urban Tree Species Classification Using a WorldView-2/3 and LiDAR Data Fusion Approach and Deep Learning. Sensors 2019, 19, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ning, X.; Zhang, J. Urban Land Cover Classification Based on WorldView-2 Image Data. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Symposium on Geomatics for Integrated Water Resource Management, Lanzhou, China, 19–21 October 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.J.; Van Niekerk, A. Identification of WorldView-2 Spectral and Spatial Factors in Detecting Salt Accumulation in Cultivated Fields. Geoderma 2016, 273, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Justice, C.; van Leeuwen, W. MODIS Vegetation Index (MOD13) Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, Version 3; University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1999. Available online: https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/atbd/atbd_mod13.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas | Mesophytes | Hygrophytes | Emergent Plants | Halophytes | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast Area | 13(60.9) | 2(8.3) | 2(7.9) | 3(6.2) | 20(83.3) |

| Northwest Area | 12(42.2) | 2(20.9) | 4(20.8) | 2(6.2) | 20(90.1) |

| Study Area | 13(46.6) | 1(14.2) | 3(17.9) | 3(8.0) | 20(86.7) |

| Parameters | Southeast Area | Northwest Area | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | 9.75 ± 5.17 | 8.33 ± 2.06 | |

| SOM | 16.80 ± 8.92 | 14.35 ± 3.55 | |

| TN | 0.93 ± 0.44 | 0.83 ± 0.20 | |

| AN | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | |

| TP | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | |

| AP | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | |

| TK | 18.54 ± 1.07 | 18.78 ± 2.09 | |

| AK | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | ** |

| SWC | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | *** |

| pH | 9.13 ± 0.13 | 9.05 ± 0.25 | |

| EC | 110.42 ± 15.28 | 419.52 ± 257.93 | *** |

| Metrics | Northwest Area | Southeast Area | Study Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| DE (%) | 49.34 | 34.66 | 25.39 |

| Intercept | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.58 |

| Obs–Pred Corr | 0.72 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.52 ** |

| TDE (%) | 38.48 | 33.82 | 25.7 |

| TSTDE (%) | 38.26 | 27.84 | 20.23 |

| MPE | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| MAE | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| RMSE | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Areas | Intervals | Average Turnover Rate (Slope) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6–1 | 0.43 | 0.04 | |

| Southeast Area | 1–1.5 | 0.30 | 0.04 |

| 1.5–2 | 0.20 | 0.02 | |

| 0.6–1 | 0.45 | 0.05 | |

| Northwest Area | 1–1.5 | 0.30 | 0.04 |

| 1.5–2 | 0.18 | 0.03 | |

| 0.6–1 | 0.42 | 0.04 | |

| Study Area | 1–1.5 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| 1.5–2 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| Variables | Southeast Area | Northwest Area | Study Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWC | 2.13 ** | 1.25 ** | |

| GEO | 0.86 ** | 1.46 ** | 0.50 ** |

| AN | 0.96 ** | ||

| Mean_B8_3 | 0.35 * | ||

| AP | 0.49 * | ||

| ASM_B4_3 | 0.19 * |

| Areas | Model Summary | Final Model 1 | Final Model 2 | Final Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Area | Number of variables | 25 | 8 | 3 |

| Deviance explained % | 33.9 | 31.4 | 25.4 | |

| Significant variables | SWC, GEO, AN, AP | SWC, GEO, AP | SWC, GEO, AP | |

| Southeast Area | Number of variables | 19 | 9 | 3 |

| Deviance explained % | 47.3 | 44.0 | 34.7 | |

| Significant variables | AN, GEO, TK, Entropy_B8_11 | AN, GEO, Mean_B8_3 | AN, GEO, Mean_B8_3 | |

| Northwest Area | Number of variables | 26 | 10 | 3 |

| Deviance explained % | 59.3 | 54.5 | 49.3 | |

| Significant variables | SWC, GEO, Contrast_B8_3 | SWC, GEO, ASM_B4_3 * | SWC, GEO, ASM_B4_3 |

| Areas | Texture Indices (Scales) | Selected Texture Indices | VI | WV-2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 5 × 5 | 7 × 7 | 9 × 9 | 11 × 11 | ||||

| Study Area | 18.9 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 18.0 |

| Southeast Area | 12.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 16.5 | 11.1 | 10.2 |

| Northwest Area | 29.2 | 26.4 | 24.1 | 25.1 | 25.4 | 32.0 | 31.8 | 22.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhao, S. Scale-Dependent Drivers of Plant Community Turnover in a Disturbed Grassland: Insights from Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling. Diversity 2025, 17, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110786

Wang Z, Guan Z, Xu L, Zhao S. Scale-Dependent Drivers of Plant Community Turnover in a Disturbed Grassland: Insights from Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling. Diversity. 2025; 17(11):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110786

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhengjun, Zhenhai Guan, Liuhui Xu, and Sishu Zhao. 2025. "Scale-Dependent Drivers of Plant Community Turnover in a Disturbed Grassland: Insights from Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling" Diversity 17, no. 11: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110786

APA StyleWang, Z., Guan, Z., Xu, L., & Zhao, S. (2025). Scale-Dependent Drivers of Plant Community Turnover in a Disturbed Grassland: Insights from Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling. Diversity, 17(11), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110786